Abstract

Background

Increased sexual risk behaviour in participants enrolled in HIV prevention trials has been a concern. The HVTN 503/Phambili study, a phase 2B study of the Merck Ad-5 multiclade HIV vaccine in South Africa, suspended enrollment and vaccinations following the results of the Step study. Participants were notified of their treatment allocation and continue to be followed. We investigated changes in risk behaviour over time and assessed the impact of study unblinding.

Methods

801 participants were enrolled. Risk behaviors were assessed with an interviewer-administered questionnaire at 6-month intervals. We assessed change from enrolment to the first 6-month assessment pre-unblinding and between enrolment and at least 6 months post-unblinding on all participants with comparable data. A one-time unblinding risk perception questionnaire was administered post-unblinding.

Results

A decrease in participants reporting unprotected sex was observed in both measured time periods for men and women, with no differences by treatment arm. At 6 months (pre-unblinding), 29.6% of men and 35.8% of women reported changing from unprotected to protected sex (p <0.0001 for each).Men (22%) were more likely than women (14%) to report behavior change after unblinding (p=0.009). Post-enrolment, 142 (45%) of 313 previously uncircumcised men underwent medical circumcision.

663 participants completed the unblinding questionnaire. More vaccine (24.6%) as compared to placebo recipients (12.0%) agreed that they were more likely to get HIV than most people (p<0.0001), and attributed this to receiving the vaccine.

Conclusion

We did not find evidence of risk compensation during this clinical trial. Some risk behaviour reductions including male circumcision were noted irrespective of treatment allocation.

Introduction

The Phambili study was the first HIV vaccine efficacy trial conducted in sub-Saharan Africa, and tested the efficacy of the Merck Adenovirus type 5(Ad5)-vectored HIV-1 vaccine in preventing HIV infection in predominantly heterosexual men and women [1]. The Phambili study suspended enrolment and vaccinations after the Step study, testing the same vaccine in the Americas, stopped early after the first interim efficacy analysis demonstrated futility. In addition, in an exploratory analysis, sub-groups of male vaccine recipients (uncircumcised menor Ad5 seropositive) in the Step study demonstrated increased risk of HIV infection [2]. Because of this, participants in the Phambili study were notified of their treatment allocation (unblinded) and follow-up including evaluation of sexual risk behaviours, continued more frequently every three months. In the Phambili study cohort, women were over 2.5 times more likely than men to become HIV infected (incidence of 6.3% [42 infections/668 person-years of follow-up] for women and 2.4% [20/837] for men) [1]. Theoretical concerns have been raised that people who participate in HIV prevention studies are at risk for sexual risk compensation [3; 4; 5; 6]. It is proposed that risk compensation may occur as a result of the dual misconceptions of being both assigned to and receiving an effective intervention fostering a false sense of hope and protection. In this report, we investigated changes in risk behaviours over time in the Phambili cohort and assessed the impact of knowledge of treatment assignment on behaviour and perception of HIV risk. Access to medical male circumcision was offered as part of risk reduction counseling for men, and thus we explored uptake of circumcision, in an era when medical circumcision for men was not readily available in South Africa.

Methods

Study Design and Population

Phambili, a phase 2Btest-of-concept HIV vaccine trial, studying the efficacy of the MRKAd5 HIV-1 gag/pol/nefsubtype B vaccine, is described in more detail elsewhere [1]. Briefly, the trial was initiated in January 2007 and was designed to enroll 3000 healthy HIV uninfected, predominantly heterosexual adults between the ages of 18–35 years at 5 sites within SA. Participants were randomised to vaccine or placebo in a blinded fashion. Because of the generalized nature of the HIV-1 epidemic in SA, the only behavioural risk eligibility criterion was self- reported sexual activity within the six months prior to enrollment. The study was approved by the ethical review committees of the Universities of the Witwatersrand, Cape Town, Limpopo and Kwazulu Natal. Participants provided written informed consent in English or their local language.

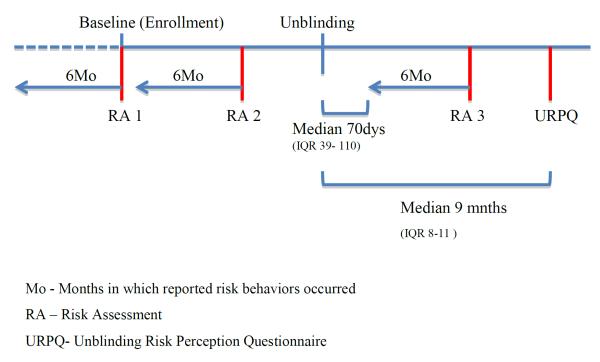

Participants completed an interviewer-administered behavioural risk assessment (RA) assessing behaviour in the prior six months to screening (baseline)(RA1) and at 6-month follow-up visits(RA2) (see Figure 1). At the enrollment visit, blood was drawn for HSV-2 testing and men were assessed for circumcision status. In addition, as part of risk reduction counseling, male participants were informed of the HIV prevention benefits of medical circumcision and each study site facilitated access to circumcision facilities for those men who expressed an interest in medical circumcision.

Figure 1.

The Phambili clinical study and timing of behavioral risk assessments.

On 19 September 2007, enrollment and vaccinations were halted based on the interim analyses of the Step study [2]. Beginning in October 2007, the 801 enrolled participants were informed of their treatment assignment (unblinded), in most cases this was done in person, and scheduled for a clinic visit for HIV testing, assessment of behavioural risk over the previous 6 months, and risk reduction counseling. After this visit, the 6-month follow-up visits continued on schedule until the site obtained regulatory approval for 3-month HIV testing and risk assessment schedule. Participants who remained HIV negative were followed for a total of 3.5 years post-enrollment. Beginning in May 2008, a one-time interviewer-administered Unblinding Risk Perception (URP) questionnaire was introduced which assessed participants' perception of acquiring HIV as compared to other people they knew; whether before unblinding they thought they had received the vaccine or placebo; if that perception influenced their behaviour before unblinding; and what, if any behaviour changes they had made after being unblinded. Figure 1 shows the timing of the risk assessments in relation to enrollment and unblinding.

Statistical Methods

Differences in risk behaviours between treatment arms, study sites, and those included or not included in the analysis cohorts were tested with two-sided Fisher's exact tests or Chi-square tests. Percentage bar graphs, with lines showing the 95% confidence intervals, display the percentages of participants reporting risk behaviours at each assessment time. Behavioural change between two time points was categorized as: reported the behavior at baseline but not at the subsequent time, did not report the behavior at baseline but subsequently did, or no change between time periods. Differences between treatment arms in the distribution of the change categories were tested with Chi-square tests. Individual level changes between time points were tested with McNemar tests to account for the correlation between the two time points for an individual. Results were considered statistically significance if p < 0.05. No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons.

Results

Data presentation

Data are presented for four analyses as described in Table I. Data are limited to risk assessments that used a 6-month reporting time period to maintain comparability with the baseline assessment. The first analysis of baseline data includes all enrolled participants. Other analyses have varying numbers because only subsets of participants who were on-study, not diagnosed with HIV infection prior to the assessment time points and in whom data was collected qualify for inclusion (Table I). To assess generalisability to the full Phambili cohort however, we compared risk behaviours at baseline for participants included in the analysis to those who had missing data for reasons other than termination from the study or diagnosis of HIV infection.

Table I.

Description and limitations of the behavioural analyses

| Name of assessment | Purpose of assessment. | Cohort | Number (men/women) | Limitationsa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (RA1) | Described risk behaviours reported for the 6 months prior to screening. | All participants enrolled in Phambili | 801 (441/360) | None |

| Six months Pre-unblinding (RA2) | Assessed changes in risk behaviours between baseline and 6 months after enrollment and prior to treatment unblinding | Participants who completed a 6-month time frame RA prior to unblinding and were not known to be HIV infected at the RA evaluation time | 245 (125/120) | 32% of participants on study at 6 months and not known to be HIV infected have data; cohort older and with less representation from the 2 sites that began enrollment later (eThekwini and MEDUNSA) with some baseline behavioural differences (Figure 2). |

| Six months Post-unblinding (RA3) | Assessed changes in risk behaviours between baseline and a 6 month time period after treatment unblinding | Participants not diagnosed with HIV infection, which completed a 6-month time frame RA at least 6 months after unblinding. | 471 (282/189) | 66% of participants on study at 6 months after unblinding and not known to be HIV infected have data; cohort has more men, is less likely to come from sites that had earlier use of the 3 month RA (Soweto and Cape Town), with some behavioural differences (Figure 2). Behavioural changes may have occurred prior to unblinding. |

| Unblinding risk perception (URPQ) | Described perceived treatment assignment prior to unblinding, changes in risk behaviours before and after unblinding, and perceived current (post-unblinding) risk of HIV infection. | Participants who completed an URP questionnaire after being unblinded to their treatment assignment and were not known to be HIV infected at the URP evaluation time. | 663 (370/293) | 93% of HIV negative participants on study when questionnaire was added have data, with men with data less likely to be HSV-2 positive. Knowledge of treatment assignment may have influenced responses. |

All analyses of risk behaviour data have the potential for recall bias and bias inherent with interviewer-administered questionnaires.

RA = risk assessment

Baseline Risk (RA1)

At baseline, 128 (29.0%) of the 441 men were circumcised and 16.4% were HSV-2 positive (Table II). During the prior 6 months, 32.0% (141/441) had 3 or more sexual partners, 58.0% (254) reported unprotected vaginal or anal intercourse, 47.4% (209) engaged in anonymous/casual sex, 39.5% (174) reported having sex after drinking or taking drugs, and 24.5% (108) drank heavily (Table II). Although only seven reported an HIV positive partner, 73.9% (326) had partners with unknown HIV status. Only two men reported anal sex with a male partner. One had one partner and practiced protective sex and the other reported two partners with whom he had both unprotected insertive and receptive anal sex.

Table II.

Baseline behavioural risk dataa by study site

| Men | ||||||

| Soweto-PHRU (N=163) | Cape Town (N=65) | KOSH (N=144) | eThekwini (N=29) | MEDUNSA (N=40) | Total (N=441) | |

| HSV-2 status**** | ||||||

| Positive | 17(10.4%) | 21 (32.3%) | 19 (13.2%) | 10 (35.7%) | 5 (12.5%) | 72 (16.4%) |

| Negative | 144 (88.3%) | 41 (63.1%) | 122 (84.7%) | 17 (60.7%) | 34 (85.0%) | 358 (81.4%) |

| Atypical | 2 (1.2%) | 3 (4.6%) | 3 (2.1%) | 1 (3.6%) | 1 (2.5%) | 10 (2.3%) |

| Circumcised**** | 45 (27.6%) | 50 (76.9%) | 22 (15.3%) | 1 (3.4%) | 10 (25.0%) | 128 (29.0%) |

| Number of sexual partners** | ||||||

| 0 | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| 1 | 62 (38.0%) | 42 (64.6%) | 56 (38.9%) | 14 (48.3%) | 20 (50.0%) | 194 (44.0%) |

| 2 | 42 (25.8%) | 17 (26.2%) | 29 (20.1%) | 8 (27.6%) | 10 (25.0%) | 106 (24.0%) |

| 3–4 | 44 (27.0%) | 6 (9.2%) | 47 (32.6%) | 4 (13.8%) | 6 (15.0%) | 107 (24.3%) |

| >=5 | 15 (9.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 12 (8.3%) | 3 (10.3%) | 4 (10.0%) | 34 (7.7%) |

| Median (range) | 2 (1,15) | 1 (1,3) | 2 (1,20) | 2 (1,6) | 2 (1,6) | 2 (1,20) |

| Any HIV positive | 4 (2.5%) | 1 (1.5%) | 1 (0.7%) | 1 (3.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (1.6%) |

| Any HIV unknown* | 130 (79.8%) | 39 (60.0%) | 105 (72.9%) | 22 (75.9%) | 30 (75.0%) | 326 (73.9%) |

| Any HIV negative | 64 (39.3%) | 36 (55.4%) | 52 (36.1%) | 13 (44.8%) | 17 (42.5%) | 182 (41.3%) |

| Unprotected vaginal/anal sex* | 104 (63.8%) | 38 (58.5%) | 68 (47.2%) | 22 (75.9%) | 24 (60.0%) | 256 (58.0%) |

| Unprotected anal sex* | 8 (4.9%) | 2 (3.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (6.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 12 (2.7%) |

| Alcohol or drug use prior to sex* | 73 (44.8%) | 20 (30.8%) | 58 (40.3%) | 5 (17.2%) | 18 (45.0%) | 174 (39.5%) |

| Had a main partner**** | 118 (72.4%) | 61 (93.8%) | 76 (52.8%) | 24 (82.8%) | 25 (62.5%) | 304 (68.9%) |

| Had a main partner 10 or more years younger** | 5 (3.1%) | 1 (1.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (13.8%) | 1 (2.5%) | 11 (2.5%) |

| Had a main partner but apart regularlyb**** | 69 (42.3%) | 42 (64.6%) | 42 (29.2%) | 20 (69.0%) | 19 (47.5%) | 192 (43.5%) |

| Had a casual/anonymous partner | 87 (53.4%) | 21 (32.3%) | 70 (48.6%) | 14 (48.3%) | 17 (42.5%) | 209 (47.4%) |

| Exchange of sex for money/gifts | 10 (6.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 10 (6.9%) | 1 (3.4%) | 3 (7.5%) | 24 (5.4%) |

| Away from home regularly*** | 42 (25.8%) | 2 (3.1%) | 34 (23.6%) | 5 (17.2%) | 11 (27.5%) | 94 (21.3%) |

| Self-reported diagnosis of an STI** | 15 (9.2%) | 3 (4.6%) | 4 (2.8%) | 5 (17.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 27 (6.1%) |

| Heavy drinkingc* | 51 (31.3%) | 14 (21.5%) | 32 (22.2%) | 1 (3.4%) | 10 (25.0%) | 108 (24.5%) |

|

| ||||||

| Women | ||||||

| Soweto-PHRU | Cape Town | KOSH | eThekwini | MEDUNSA | Total | |

| Total Enrolled | 145 (100.0%) | 101 (100.0%) | 77 (100.0%) | 24 (100.0%) | 13 (100.0%) | 360 (100.0%) |

| HSV-2 status**** | ||||||

| Positive | 75 (51.7%) | 67 (66.3%) | 20 (26.0%) | 11 (47.8%) | 4 (30.8%) | 177 (49.3%) |

| Negative | 68 (46.9%) | 32 (31.7%) | 56 (72.7%) | 12 (52.2%) | 9 (69.2%) | 177 (49.3%) |

| Atypical | 2 (1.4%) | 2 (2.0%) | 1 (1.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (1.4%) |

| Number of sexual partners | ||||||

| 0 | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| 1 | 118 (81.4%) | 92 (91.1%) | 62 (80.5%) | 21 (87.5%) | 11 (84.6%) | 304 (84.4%) |

| 2 | 25 (17.2%) | 8 (7.9%) | 10 (13.0%) | 3 (12.5%) | 2 (15.4%) | 48 (13.3%) |

| 3–4 | 2 (1.4%) | 1 (1.0%) | 5 (6.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 8 (2.2%) |

| >=5 | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Median (range) | 1 (1,3) | 1 (1,3) | 1 (1,3) | 1 (1,2) | 1 (1,2) | 1 (1,3) |

| Any HIV positive | 2 (1.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (4.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (0.8%) |

| Any HIV unknown | 62 (42.8%) | 47 (46.5%) | 47 (61.0%) | 13 (54.2%) | 6 (46.2%) | 175 (48.6%) |

| Any HIV negative | 91 (62.8%) | 57 (56.4%) | 35 (45.5%) | 11 (45.8%) | 8 (61.5%) | 202 (56.1%) |

| Unprotected vaginal/anal sex | 89 (61.4%) | 51 (50.5%) | 43 (55.8%) | 12 (50.0%) | 6 (46.2%) | 201 (55.8%) |

| Unprotected anal sex | 4 (2.8%) | 2 (2.0%) | 2 (2.6%) | 1 (4.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 9 (2.5%) |

| Alcohol or drug use prior to sex* | 25 (17.2%) | 5 (5.0%) | 8 (10.4%) | 1 (4.2%) | 1 (7.7%) | 40 (11.1%) |

| Had a main partner**** | 124 (85.5%) | 97 (96.0%) | 48 (62.3%) | 21 (87.5%) | 12 (92.3%) | 302 (83.9%) |

| Had a main partner 10 or more years older** | 7 (4.8%) | 6 (5.9%) | 5 (6.5%) | 7 (29.2%) | 2 (15.4%) | 27 (7.5%) |

| Had a main partner but apart regularlyb* | 55 (37.9%) | 58 (57.4%) | 28 (36.4%) | 12 (50.0%) | 4 (30.8%) | 157 (43.6%) |

| Had a casual/anonymous partner | 22 (15.2%) | 8 (7.9%) | 6 (7.8%) | 3 (12.5%) | 1 (7.7%) | 40 (11.1%) |

| Exchange of sex for money/gifts | 1 (0.7%) | 1 (1.0%) | 1 (1.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (7.7%) | 4 (1.1%) |

| Forced to have sex | 5 (3.4%) | 2 (2.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (1.9%) |

| Self-reported diagnosis of an STI | 11 (7.6%) | 4 (4.0%) | 2 (2.6%) | 1 (4.2%) | 1 (7.7%) | 19 (5.3%) |

| Heavy drinkingc | 11 (7.6%) | 4 (4.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (4.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 16 (4.4%) |

Significant p-values for differences by study site are indicated as * <0.05 – 0.01, ** <0.01–0.001, *** O.001 - 0.0001, and **** <0.0001.

Behavioural risk data, except for circumcision and HSV-2 status, are self-reported behaviours that occurred within the 6 months prior to screening.

Apart regularly from main partner is defined as living in a different location or partner regularly away from home for 3 or more days per week or in addition for men, being away from home for 3 or more days per week.

Heavy drinking is defined as having >5 drinks per day on at least 10 days within the six month reporting period.

At baseline, amongst men, there were no statistical differences by treatment arm in reported risk behaviours [1], but there was a significant difference in risk profiles by study site (Table II). Cape Town had a high percentage of HSV-2 positive men, the highest number circumcised, and the most with only one sexual partner. Men from the eThekwini site reported the lowest percentages using alcohol or drugs prior to sex and with heavy drinking.

Women reported less risky behaviour than men in terms of number of sexual partners, exchange of money or gifts for sex, having a casual or anonymous partner, having sex after drinking or taking drugs, and heavy drinking. Among the 360 enrolled women, 84.4% (304) reported having only one sexual partner, but with a high rate (201, 55.8%) of unprotected vaginal or anal sex (Table II). Almost half (157, 43.6%) had a main partner that did not reside permanently with them, 11.1% (40) reported casual/anonymous sex. Only 3 reported an HIV positive partner, 56.1% (202) had HIV negative partners and 48.6% (175) had unknown status partners. The only statistically significant difference by treatment arm at baseline was for women reporting having sex after drinking or taking drugs, 15% (26/178) of vaccine and 8% (14/182) of placebo recipients (p = 0.04) [1]. Women were more homogeneous across the study sites than men in reported numbers of partners and unprotected sex. Similar to men, women from Cape Town were more likely to be HSV-2 positive (p <0.0001).

Less than 8% of men or of women reported at baseline and on subsequent RAs having an HIV positive partner, having unprotected anal sex, having a main partner older (women) or younger (men) by ten years, exchange of sex, forced sex, or self-reported STIs so we do not discuss these further and combine unprotected vaginal and anal sex in subsequent analyses.

Behavioural change over a six-month period between baseline and before unblinding (RA2)

Since the study was stopped whilst participants were still being enrolled, only 32% (245/759, 125 men, 120 women) of HIV negative participants on study had a 6-month behavioural RA prior to unblinding (Table I). There were no treatment arm differences between this cohort and those not included (data not shown). Importantly, for men and women, there were no statistically significant differences by treatment arm in risk behaviours reported at baseline or at six months, or in the pattern of behavior change between assessment times.

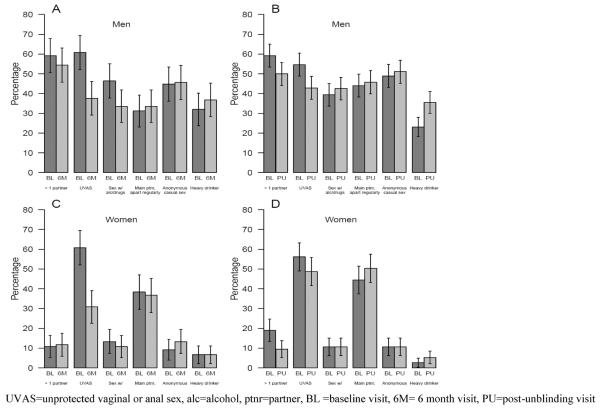

Both men and women had a significant reduction in unprotected vaginal or anal sex between enrollment and 6 months on study (p < 0.0001 for both; figure 2 and table III).Men also reported less sex following alcohol or drug use (p = 0.03). No significant change was seen in the numbers reporting multiple partners for either men or women. Between assessments, 18.4% (23) of men and 7.5% (9) of women changed from having multiple sex partners to having at most one partner (Table III). However, 13.6% (17) of men and 8.3% (10) of women changed from being monogamous to having multiple partners.

Figure 2.

Change in risk behaviours between baseline and 6 months on study (A and C for men and women respectively) and between baseline and post-unblinding (B and D for men and women respectively).

Table III.

Change in unprotected sex and multiple partners between behavioural risk assessments

| Men | p-valuea | Women | p-valuea | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Between baseline and 6 months (pre-unblinding) b | N=125 | N=120 | N=245 | ||

| Unprotected vaginal/anal sex | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||

| No change | 80 (64.0%) | 70 (58.3%) | 150 (61.2%) | ||

| Change from some to none | 37 (29.6%) | 43 (35.8%) | 80 (32.7%) | ||

| Change from none to some | 8 (6.4%) | 7 (5.8%) | 15 (6.1%) | ||

| Multiple partners | 0.43 | 1.0 | |||

| No change | 85 (68.0%) | 101 (84.2%) | 186 (75.9%) | ||

| Change from > 1 to 0–1 partners | 23 (18.4%) | 9 (7.5%) | 32 (13.1%) | ||

| Change from 0–1 to > 1 partners | 17 (13.6%) | 10 (8.3%) | 27 (11.0%) | ||

| Between baseline and at least 6 months post-unblinding) | N=282 | N=189 | N=471 | ||

| Unprotected vaginal/anal sex | 0.004 | 0.12 | |||

| No change | 161 (57.1%) | 119 (63.0%) | 280 (59.4%) | ||

| Change from some to none | 77 (27.3%) | 42 (22.2%) | 119(25.3%) | ||

| Change from none to some | 44 (15.6%) | 28 (14.8%) | 72 (15.3%) | ||

| Multiple partners | 0.01 | 0.005 | |||

| No change | 180 (63.8%) | 151 (79.9%) | 331 (70.3%) | ||

| Change from > 1 to 0–1 partners | 64 (22.7%) | 28 (14.8%) | 92 (19.5%) | ||

| Change from 0–1 to > 1 partners | 38 (13.5%) | 10 (5.3%) | 48 (10.2%) |

p-values are from McNemar's tests.

The majority of enrolled participants had not reached the 6 month time point prior to unblinding.

Behaviour change between baseline and after unblinding. (RA3)

Data were available for 471 participants (282 men, 189 women) to assess change in behaviour between the 6 month period prior to baseline and after treatment unblinding. Compared to the 244 HIV negative participants not included in the analysis, there were no differences with respect to treatment arm.

There were no significant differences between treatment arms in risk behaviours reported at baseline or at the post-unblinding assessment. The only difference seen in behavior change between the two assessments occurred in men where more in the placebo arm than vaccine arm reported that they had sex after alcohol or drug use, with similar numbers increasing and decreasing this behaviour (p = 0.01) (data not shown).

Fewer participants reported unprotected sex after unblinding, although the change is statistically significant for men only (p = 0.004, Figure 2, table 3). The changes in reported multiple partners were significant for both men (p=0.01) and women (p=0.005); 22.7% (64) of men and 14.8% (28) of women who had multiple partners at baseline reported 0 or 1 partners post-unblinding. Of some concern, 13.5% (38) of men and 5.3% (10) of women changed from being monogamous to having multiple partners and 15.6% (44) of men and 14.8% (28) women changed from having protected to some unprotected sex.”. Men also reported an increase in heavy drinking (p = 0.0002) (figure 2).

Unblinding Risk Perception Questionnaire. (URPQ)

Among the 663 participants (370 men and 293 women) included in the URP questionnaire analysis, the median time between unblinding and questionnaire administration was 9.1 months (IQR 7.8 to 11.0 months). An additional 51 HIV uninfected participants on-study as of May 2008 did not complete a URP questionnaire, with no difference in completion rates by site or treatment arm.

When asked, on average nine months after being unblinded, to reflect upon what treatment they thought they received prior to unblinding, 41.8% (277) replied they didn't know. Among those who had a perception, 52.3% had correctly perceived their treatment assignment, but similar numbers in both treatment groups thought they received vaccine (71.3% on the vaccine arm and 64.4% on placebo). About 14% in each treatment arm said that this treatment perception influenced their pre-unblinding behavior, more so for men (18.1%) than woman (8.7%), p = 0.01. There was no statistically significant difference between the treatment arms in reported risk behavior change after unblinding (19.5% vaccinees, 17.7% placebos). Overall, men were more likely to report behaviour change after unblinding than women (22.2% vs. 14.0%, p=0.009). Among the 123 who reported post-unblinding behavior change, there were no gender differences in the type of change, except men were more likely to reply that they reduced their number of partners (57.3% men, 9.8% women, p < 0.001).Other reported behavior changes were: increased condom use (65.0%); encouraged main partner to be tested (48.8%); discussed HIV prevention or safe sex with main partner (48.0%); reduced the frequency of sex (20.3%). Eleven (8 men, 3 women) responded that they increased the frequency of sex or their number of sex partners.

A higher percentage of participants in the vaccine arm compared with placebo recipients agreed that they were more likely to get HIV/AIDS than most people (24.6% vaccine and 12.0% placebo, p < 0.0001). Among those agreeing, placebo recipients were more likely to say that this perception was due to having more unprotected sex than most people, whereas vaccine recipients replied more frequently that it was due to receiving the vaccine.

Post-enrollment Circumcision

In total, 142 (45.4%) men uncircumcised at enrollment received post-enrollment circumcision (table IV), this did not differ by treatment arm. The majority of men from Cape Town were circumcised at enrollment. Circumcision uptake differed by study site, with men from the eThekwini and Soweto sites significantly more likely to access circumcision as compared to the MEDUNSA or KOSH site (table IV). The rate of circumcision was higher before unblinding than after (0.56 [56 over 100 person-years] pre and 0.19 [86 over 452 person-years] post-unblinding).

Table IV.

Post-enrollment circumcision

| Soweto-PHRU | Cape Town | KOSH | eThekwini | Medunsa | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uncircumcised at Enrollment | 118 (100.0%) | 15 (100.0%) | 122 (100.0%) | 28 (100.0%) | 30 (100.0%) | 313 (100.0%) |

| Post-enrollment Circumcision | ||||||

| Yes | 68 (57.6%) | 7 (46.7%) | 44 (36.1%) | 22 (78.6%) | 1 (3.3%) | 142 (45.4%) |

| No | 49 (41.5%) | 7 (46.7%) | 74 (60.7%) | 6 (21.4%) | 29 (96.7%) | 165 (52.7%) |

| No post-enr assessment | 1 (0.8%) | 1 (6.7%) | 4 (3.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 6 (1.9%) |

| Timing of circumcision from enrollment (n=142) | ||||||

| <= 1 month | 6 (8.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (4.5%) | 10 (45.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 18 (12.7%) |

| > 1 – 3months | 19 (27.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (9.1%) | 4 (18.2%) | 1 (100.0%) | 28 (19.7%) |

| >3 – 6 months | 12 (17.6%) | 1 (14.3%) | 9 (20.5%) | 3 (13.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 25 (17.6%) |

| > 6 months - 1 year | 9 (13.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 14 (31.8%) | 2 (9.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 25 (17.6%) |

| > 1 – 2 years | 8 (11.8%) | 3 (42.9%) | 7 (15.9%) | 2 (9.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 20 (14.1%) |

| > 2 years | 14 (20.6%) | 3 (42.9%) | 8 (18.2%) | 1 (4.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 26 (18.3%) |

| Timing of circumcision to unblinding (n=142) | ||||||

| Pre-unblinding | 30 (44.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 12 (27.3%) | 14 (63.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 56 (39.4%) |

| Post-unblinding | 38 (55.9%) | 7 (100.0%) | 32 (72.7%) | 8 (36.4%) | 1 (100.0%) | 86 (60.6%) |

| Method of assessment (n=142) | ||||||

| Clinical | 38 (55.9%) | 2 (28.6%) | 5 (11.4%) | 2 (9.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 47 (33.1%) |

| Self-report | 30 (44.1%) | 5 (71.4%) | 39 (88.6%) | 20 (90.9%) | 1 (100.0%) | 95 (66.9%) |

Discussion

The Phambili study enrolled participants at high risk for HIV acquisition, evidenced by the high rates of incident HIV in both vaccine and placebo arms (4.54 vs. 3.70 per 100 person years of follow up respectively). [1].

At baseline, we report high rates of unprotected vaginal and/or anal sex, similar to that reported in other HIV prevention studies [7; 8]. We found no evidence of behavioral disinhibition in this study, with the majority of participants reporting no change in risk behaviours compared to baseline, and a substantial percentage reporting a decline in unprotected sexual intercourse, possibly due to risk reduction counseling. Multiple partners is a recognized HIV risk factor and whilst overall there was a reduction in partner numbers, some participants showed an increase in partner numbers. This suggests that participants will take sexual risks despite risk reduction counseling.

This study, like others conducted in South Africa, demonstrated that many participants reported more condom use over the course of the study [8; 9].

The term therapeutic misconception occurs when “research subjects fail to recognize the ways in which research participation may involve the sacrifice of some degree of personal care” [10]. Simon, et al suggested that there was a need for a definition of misconception specific to trials of prevention and dubbed “Preventive misconception” and defined it as “the overestimate in probability or level of personal protection that is afforded by being enrolled in a trial of a preventive intervention”[3].

Concerns related to preventive misconception have not been borne out in a number of HIV prevention studies [11; 12; 13], and in other HIV vaccine efficacy trials [14; 15; 16]. In the Step study, the proportion of study participants reporting risk declined substantially during the first 6 months of the study, and remained relatively low over 18 months of follow-up [2; 16]. This is in contrast to other reports where it is thought that misunderstanding may have lead to sexual disinhibition. Chesney, et al reported rates of unprotected anal intercourse increased from 9% at baseline to 20% at 12 months during phase 1 and 2 HIV vaccine trials and a predictor of unprotected anal intercourse included reported hope of protection from HIV infection [17]. Bartholomew and colleagues, observe in their study of a three-year vaccine efficacy trial, that although perceived intervention efficacy was not found to be associated with increased risk taking, perceived study assignment appeared to be a significant factor[14].

Perceptions of treatment assignment prior to unblinding in Phambili had little or no effect on risk behaviour. Since assignment perception was part of the URP questions and these were asked after unblinding, it is uncertain if these results truly represent pre-unblinding perceptions. But the result of no treatment arm differences in behaviours reported at the 6-month pre-unblinding visit among a subset of the cohort gives credence to the findings that a majority of people did not correctly guess their treatment assignment pre-unblinding and did not change behaviour based on this perception. After unblinding, vaccine recipients perceived themselves to be at higher risk of HIV infection, which may relate to participant understanding of the reasons why enrolment and vaccinations were halted in the study.

With unblinding occurring so early in the study we are unable to report on longer-term behavior change in this cohort. Other behavioural intervention studies have shown that efforts to reduce HIV risk through behavior change only are difficult to sustain [18]. We were also unable to assess the pattern of behavioural change between baseline, preunblinding and post-unblinding due to the limited numbers of participants with risk assessment data at these three time points. Besides limited questions on condom use, we relied on an interviewer-administered instrument, which has the potential for underreporting of behaviours for reasons of social desirability.

The uptake of medical male circumcision post-enrolment is encouraging, especially the high uptake of circumcision seen at the eThekwini site, situated in Kwazulu-Natal, an area of the country where traditional male circumcision is not practiced. The results presented here also speak to the heterogeneity in male circumcision practices in South Africa [19]. More research in prevention trials evaluating male circumcision uptake and the barriers to circumcision in this setting will assist in understanding how this strategy can be offered as standard of prevention by trial sites.

A limitation of our analysis is that pre- and post-unblinding RA data are not available for the entire study cohort. This was unavoidable as the trial involved 5 study sites which commenced enrolment at different times, was unblinded relatively early in the trial process and protocol amendments to deal with changes in follow-up were approved at different times. However, the URP questionnaire and available RA data give insights into at least short term behavior change following baseline risk assessment, the impact of unblinding and the impact of assignment perception on behaviours after enrollment. Overall, this study confirms, in keeping with other recently reported HIV prevention trials- that there is no evidence for risk compensation and that trial participants can and do assimilate new information and modify their behavior accordingly.

Highlights

Risk behavior over time in the first HIV efficacy trial in South Africa is reported

No evidence of sexual risk compensation is observed

Good uptake of medical circumcision among male participants

Acknowledgements

We thank the Phambili Study volunteers and the staff and community members at each of the Phambili Study sites.

Members of the HVTN 503 study team include:

HVTN, Seattle: Sarah Alexander, Larry Corey, Constance Ducar, Ann Duerr, Niles Eaton, Julie McElrath, Renée Holt. John Hural, Jim Kublin, Margaret Wecker. SCHARP, Seattle: Gina Escamilla, Drienna Holman, Barbara Metch, Zoe Moodie, Steve Self. DAIDS, Washington DC: Mary Allen, Alan Fix, Dean Follman, Peggy Johnston, Mary Anne Luzar, Ana Martinez. Merck Research Lab: Danny Casimiro, Robin Isaacs, Lisa Kierstead, Randi Leavitt, Devan Mehrotra, Mike Robertson. Perinatal Health Research Unit, Soweto: Guy DeBruyn, Glenda Gray, Busi Nkala, Tebogo Magopane, Baningi Mkhise. Medunsa, Pretoria: Innocentia Lehobye, Matsontso (Peter) Mathebula, Maphoshane Nchabeleng. Desmond Tutu HIV Centre, Cape Town: Linda-Gail Bekker, Agnes Ronan, Surita Roux, Daniella Mark. The Aurum Institute, Klerksdorp: Gavin Churchyard, Mary Latka, Carien Lion-Cachet Kathy Mngadi, Tanya Nielson, Pearl Selepe. CAPRISA, Durban: Thola Bennie, Koleka Mlisana, Nivashnee Naicker. NICD, Sandringham: Adrian Puren. Community Representative: David Galetta. SAAVI, Cape Town: Elise Levendal

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Authors Contributions: Conducted the analyses: BM, ZM

Analyzed the data: BM, ZM

Designed study, wrote, reviewed and approved the manuscript: GEG, LGB, MA, ZM, BM, GC, MN, KM, MR, JGK.

Conducted the Phambili study, oversaw study, managed participants: GEG, GC, LGB, NM, KM.

Final editing: LGB, GEG, MA, ZM, BM

References

- [1].Gray GE, Allen M, Moodie Z, Churchyard G, Bekker LG, Nchabeleng M, et al. on behalf of The HVTN 503/Phambili study team Safety and efficacy of the HVTN 503/Phambili Study of a clade-B-based HIV-1 vaccine in South Africa: a double blind, Randomized, placebo-controlled test-of-concept phase 2b study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011 Jul;11(7):507–515. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70098-6. Epub 2011 May 11. PubMed PMID: 21570355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Buchbinder SP, Mehrotra DV, Duerr A, Fitzgerald DW, Mogg R, Li D, et al. Efficacy Assessment of a cell-mediated immunity HIV-1 vaccine (the Step Study): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, test-of-concept trial. Lancet. 2008 Nov 29;372(9653):1881–93. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61591-3. Epub 2008 Nov 13. PubMed PMID: 19012954; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2721012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Simon AE, Wu AW, Lavori PW, Sugarman J. Preventive misconception. Its nature, presence and ethical implications for research. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(5):370–374. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Cassell MM, Halperin DT, Shelton JD, Stanton D. Risk compensation: the Achilles' heel of innovations in HIV prevention? BMJ. 2006 Mar 11;332(7541):605–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7541.605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Pinkerton SD. Sexual risk compensation and HIV/STD transmission: empirical evidence and theoretical considerations. Risk Anal. 2001 Aug;21(4):727–36. doi: 10.1111/0272-4332.214146. PubMed PMID: 11726023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Eaton LA, Kalichman S. Risk compensation in HIV prevention: implications for vaccines, microbicides, and other biomedical HIV prevention technologies. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2007 Dec;4(4):165–72. doi: 10.1007/s11904-007-0024-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Padian NS, van der Straten A, Ramjee G, Chipato T, de Bruyn G, Blanchard K, et al. MIRA Team Diaphragm and lubricant gel for prevention of HIV acquisition in southern African women: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007 Jul 21;370(9583):251–61. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60950-7. PubMed PMID: 17631387; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2442038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Abdool Karim Q, Abdool Karim SS, Frohlich JA, Grobler AC, Baxter C, Mansoor LE, et al. CAPRISA004 Trial Group Effectiveness and safety of tenofovir gel, an antiretroviral microbicide, for the prevention of HIV infection in women. Science. 2010 Sep 3;329(5996):1168–74. doi: 10.1126/science.1193748. Epub 2010 Jul 19. Erratum in: Science. 2011 Jul 29;333(6042):524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu AY, Vargas L, et al. iPrEx Study Team. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010 Dec 30;363(27):2587–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205. Epub 2010 Nov 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Appelbaum P, Lidz C, Grisso T. Therapeutic misconception in Clinical Research: Frequency and risk factors. IRB:Ethics and Human Research. 2004;26(No.2):3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Guest G, Shattuck D, Johnson L, Akumatey B, Clarke EE, Chen PL, et al. Changes in sexual risk behavior among participants in a PrEP HIV prevention trial. Sex Transm Dis. 2008 Dec;35(12):1002–8. PubMed PMID: 19051397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Martin JN, Roland ME, Neilands TB, Krone MR, Bamberger JD, Kohn RP, et al. Use of postexposure prophylaxis against HIV infection following sexual exposure does not lead to increases in high-risk behavior. AIDS. 2004 Mar 26;18(5):787–92. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200403260-00010. PubMed PMID: 15075514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Agot KE, Kiarie JN, Nguyen HQ, Odhiambo JO, Onyango TM, Weiss NS. Male circumcision in Siaya and Bondo Districts, Kenya: prospective cohort study to assess behavioral disinhibition following circumcision. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007 Jan 1;44(1):66–70. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000242455.05274.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bartholow BN, Buchbinder S, Celum C, Goli V, Koblin B, Para M, et al. VISION/VAX004Study Team. HIV sexual risk behavior over 36 months of follow-up in the worlds first HIV vaccine efficacy trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005 May 1;39(1):90–101. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000143600.41363.78. PubMed PMID: 15851919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lampinen TM, Chan K, Remis RS, Merid MF, Rusch M, Vincelette J, et al. Sexual risk behaviour of Canadian Participants in the first efficacy trial of a preventive HIV-1 vaccine. CMAJ. 2005 Feb 15;172(4):479–83. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1031785. PubMed PMID: 15710939; PubMed Central PMCID:PMC548409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Koblin BA, Mayer KH, Noonan E, Wang CY, Marmor M, Sanchez J, et al. Sexual risk behaviors, circumcision status and pre-existing immunity to adenovirus type 5 among men who have sex with men participating in a randomized HIV-1 vaccine efficacy trial: Step Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012 Mar 14; doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31825325aa. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Chesney MA, Chambers DB, Kahn JO. Risk behavior for HIV infection in participants in preventive HIV vaccine trials. A cautionary note. J Acquir immune Immune Defic Syndr Human Retrovirol. 1997;16:266–71. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199712010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]