Abstract

Objective

There are approximately 8.5 million Alzheimer disease (AD) patients who need anesthesia and surgery care every year. The inhalation anesthetic isoflurane, but not desflurane, has been shown to induce caspase activation and apoptosis, which are part of AD neuropathogenesis, through the mitochondria-dependent apoptosis pathway. However, the in vivo relevance, underlying mechanisms, and functional consequences of these findings remain largely to be determined.

Methods

We therefore set out to assess the effects of isoflurane and desflurane on mitochondrial function, cytotoxicity, learning, and memory using flow cytometry, confocal microscopy, Western blot analysis, immunocytochemistry, and the fear conditioning test.

Results

Here we show that isoflurane, but not desflurane, induces opening of mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP), increase in levels of reactive oxygen species, reduction in levels of mitochondrial membrane potential and adenosine-5′-triphosphate, activation of caspase 3, and impairment of learning and memory in cultured cells, mouse hippocampus neurons, mouse hippocampus, and mice. Moreover, cyclosporine A, a blocker of mPTP opening, attenuates isoflurane-induced mPTP opening, caspase 3 activation, and impairment of learning and memory. Finally, isoflurane may induce the opening of mPTP via increasing levels of reactive oxygen species.

Interpretation

These findings suggest that desflurane could be a safer anesthetic for AD patients as compared to isoflurane, and elucidate the potential mitochondria-associated underlying mechanisms, and therefore have implications for use of anesthetics in AD patients, pending human study confirmation.

Advancing age is among the major risk factors for Alzheimer disease (AD), with an incidence of 13% in people >65 years of age (2011 AD Facts and Figures, Alzheimer’s Association, 2011).1 Globally, about 66 million patients aged >65 years have surgery under anesthesia each year.2 Taken together, there are approximately 8.5 million (13% of 66 million) AD patients who need anesthesia and surgery care every year. Anesthesia and surgery have been reported to induce cognitive dysfunction, to which AD patients are susceptible.3 Therefore, there is a need to identify anesthetic(s) that will not induce or that will induce to a lesser degree AD neuropathogenesis and cognitive dysfunction. This opinion has been emphasized in the fields of both AD and anesthesia research.4

The commonly used inhalation anesthetic isoflurane has been shown to induce caspase activation and apoptosis, and to increase β-amyloid protein (Aβ) oligomerization and accumulation in vitro and in vivo.5–13 Desflurane, another commonly used inhalation anesthetic, may not induce these detrimental effects in cultured cells.13,15,16 Consequently, it is important to further assess in vivo relevance, underlying mechanisms, and functional consequences (eg, learning and memory) of these observations. Therefore, we set out to determine whether isoflurane and desflurane may have different effects on learning and memory function and on mitochondrial function (eg, mitochondrial permeability transition pore [mPTP] opening).

Isoflurane, but not desflurane, could induce the caspase activation and apoptosis through the mitochondria-dependent apoptosis pathway.16 Mitochondrial dysfunction can lead to caspase activation and apoptosis, potentially through opening of mPTP, reductions in mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP), and decreases in generation of adenosine-5′-triphosphate (ATP).17–19 Specifically, in physiological conditions, the inner mitochondrial membrane is nearly impermeable to all ions.20 Thus, mitochondria exhibit a high MMP, which is generated by the respiratory chain and is necessary for ATP generation.17–19 Conversely, in pathological conditions (eg, brain injury), the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and cytosolic calcium levels may induce status of mitochondrial permeability transition or the opening of mPTP. Opening of mPTP will then cause increased entry of small solutes into the mitochondrial matrix driven by electrochemical forces, which leads to dissipation (eg, reduction) of MMP, decreased ATP levels, and ultimately cytotoxicity (eg, caspase activation).17–19,21–25

In the present study, we have assessed effects of isoflurane and desflurane on mPTP, MMP, ATP, caspase 3 activation, and learning and memory function in vitro and in vivo. Cyclosporine A (CsA), a blocker of mPTP opening,22,23,26–31 was used to further determine the extent to which isoflurane may cause cytotoxicity and impairment of learning and memory by inducing opening of mPTP.

Materials and Methods

Cells and Mouse Hippocampus Neurons

We employed H4 human neuroglioma cells, stably transfected to express full-length amyloid precursor protein (H4-APP cells), rat neuroblastoma cells (B104 cells), and mouse hippocampus neurons in experiments (Supplementary Methods).

Treatments for H4-APP Cells, B104 Cells, and Mouse Hippocampus Neurons

H4-APP cells, B104 cells, or mouse hippocampus neurons were treated with 2% isoflurane or 12% desflurane plus 21% O2 and 5% CO2 for 6 hours as described by Xie et al8 and Zhang et al14 for measurement of caspase 3 activation, MMP and ROS. The cells and neurons were treated for 3 hours for measurement of mPTP and ATP levels, because we wanted to assess whether isoflurane or desflurane can induce mPTP opening and reduction of ATP levels without cell death. Staurosporine (STS, 100 nM) was used as a positive control in the studies. In the interaction experiments, 1μM CsA or 1mM N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) was administrated to cells 1 hour before isoflurane treatment (see Supplementary Methods).

Mice Anesthesia and Harvest of Brain Tissues

6-day-old C57BL/J6 mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were used in the experiments as described before.8,32 In the interaction studies, CsA (10mg/kg) was administered to mice via intraperitoneal injection 30 minutes before treatment with isoflurane or desflurane. Whole brain tissues or hippocampus tissues of mice were harvested at the end of isoflurane or desflurane anesthesia (see Supplementary Methods).

Brain Tissue Lysis, Protein Amount Quantification, and Western Blot Analysis

The harvested brain or hippocampus tissues were homogenized on ice using an immunoprecipitation buffer (10mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150mM NaCl, 2mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 0.5% Nonidet P-40) plus protease inhibitors (1μg/ml aprotinin, 1μg/ml leupeptin, 1μg/ml pepstatin A). The lysates were collected, centrifuged at 13,000rpm for 15 minutes, and quantified for total proteins by a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Pierce, Iselin, NJ). The harvested H4-APP cells, B104 cells, mouse hippocampus neurons, and brain tissues were subjected to Western blot analyses as described by Xie et al8–10 and Zhang et al16,33 (see Supplementary Methods).

ROS Measurement

An OxiSelect Intracellular ROS Assay Kit and an OxiSelect In Vitro ROS/RNS Assay Kit (Cell Biolabs, San Diego, CA) were used to measure the amount of ROS in vivo and in vitro, respectively, according to protocols provided by company (see Supplementary Methods).

Flow Cytometric Analysis of mPTP Opening

Opening of mPTP was determined by flow cytometry, using an MitoProbe Transition Pore Assay Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA; see Supplementary Methods).

Determination of MMP

We used tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester and perchlorate (TMRE; Sigma, St Louis, MO), and a 5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′ tetraethylbenzimidazolylcarbocyanine iodide (JC-1) mitochondrial membrane potential detection kit (Biotium, Hayword, CA) to determine MMP levels according to the manufacturer’s protocol (see Supplementary Methods).

ATP Measurement

We employed an ATP Determination Kit (Invitrogen) in experiments to detect ATP levels according to a protocol provided by the company (see Supplementary Methods).

Fear Conditioning Test

A fear conditioning test (FCT) was performed as described by Saab et al33 with modification (see Supplementary Methods).

Statistics

Given the presence of background caspase activation, MMP, and ROS levels in cells and brain tissues of mice, we did not use absolute values to describe these changes. Instead, ROS, MMP, and caspase activation were presented as a percentage of those of the control group. One hundred percent caspase activation, MMP, or ROS refers to control levels for purposes of comparison to experimental conditions. Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The number of samples varied from 3 to 12, and the samples were normally distributed (tested by normality). For the FCT freezing times for both context and tone tests of the FCT were used to determine function of learning and memory. Freezing times in both treated and control mice were presented. Data were expressed as mean ± SD. The number of samples in each anesthesia or control group was 10. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measurements or t test was used to compare difference from control group. Two-way ANOVA was used to analyze interaction between isoflurane and CsA on caspase 3 activation, ROS, and freezing time of FCT. Probability values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. SAS software (Cary, NC) was used to analyze the data.

Results

Isoflurane, but Not Desflurane, Induces the Opening of mPTP

We assessed effects of isoflurane and desflurane on opening of mPTP, levels of MMP and ATP, and caspase 3 activation in B104 cells, H4-APP cells, and mouse hippocampus neurons. We employed H4-APP cells because we have found that isoflurane, but not desflurane, can induce caspase 3 activation in H4-APP cells.9,15 We included B104 cells in the experiments because H4-APP cells and primary neurons are not suitable for flow cytometry studies owing to potential for autofluorescence (H4-APP cells) and the characteristic of attaching to each other (neurons).

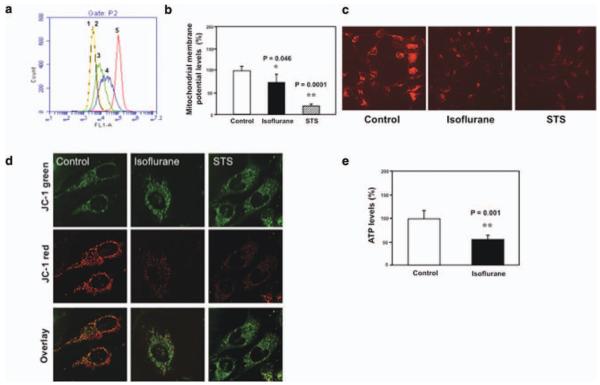

Flow cytometric analysis of immunocytochemistry staining of calcein AM and cobalt showed that treatment with 2% isoflurane for 3 hours induced the opening of mPTP as compared to the control condition in B104 cells (Fig 1). This is evidenced by an increase in the intensity of fluorescence in the cells treated by isoflurane (see Fig 1A, peak 3) or ionomycin (peak 2, the positive control) as compared to that detected in negative control (peak 4). These findings suggest that isoflurane may induce cytotoxicity (eg, caspase activation and apoptosis) through opening of mPTP. Next, JC-1 fluorescence analysis showed that isoflurane and STS reduced levels of MMP in H4-APP cells. Immunocytochemistry staining of TMRE and JC-1, the indicators of MMP, showed that isoflurane treatment decreased levels of MMP, detected by confocal microscopy, in H4-APP cells. The treatment with 100 nM STS, the positive control in the studies, also decreased MMP. Finally, we found that treatment with 2% isoflurane for 3 hours decreased ATP levels without cell death (data not shown) in H4-APP cells.

FIGURE 1.

Isoflurane induces opening of mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP), and decreases levels of mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) and adenosine-5′-triphosphate (ATP) in B104 cells and H4-APP cells. (a) Flow cytometric analysis shows changes in calcein levels in mitochondria of B104 cells stained with calcein AM or calcein AM plus cobalt, which indicates opening of mPTP: peak 1, unstained B104 cells; peak 2, positive control (treatment of calcein AM plus cobalt and ionomycin); peak 3, cells treated with calcein AM plus cobalt and isoflurane; peak 4, negative control (treatment of calcein AM plus cobalt); peak 5, calcein AM treated B104 cells. The changes in intensity of fluorescence between isoflurane group (peak 3), positive control (peak 2), and negative control (peak 4) suggest that isoflurane induces opening of mPTP. (b) Tetraethylbenzimidazolylcarbocyanine iodide (JC-1) fluorescence analysis shows that isoflurane (black bar) or staurosporine (STS; net bar) reduces levels of MMP as compared to control condition. (c) Isoflurane or STS may decrease levels of MMP, detected by staining of tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester and perchlorate, the MMP-dependent fluorescent indicator, as compared to control condition. (d) Isoflurane or STS may decrease levels of MMP, detected by JC-1 staining, as compared to control condition. The first row illustrates that there is no significant difference of JC-1 green staining following treatments of control condition, isoflurane, and STS. The second row illustrates that isoflurane or STS may decrease MMP, detected by JC-1 red staining, as compared to control condition. The third row is an overlay of JC-1 green and JC-1 red staining. (e) Isoflurane reduces ATP levels (black bar) as compared to control condition (white bar).

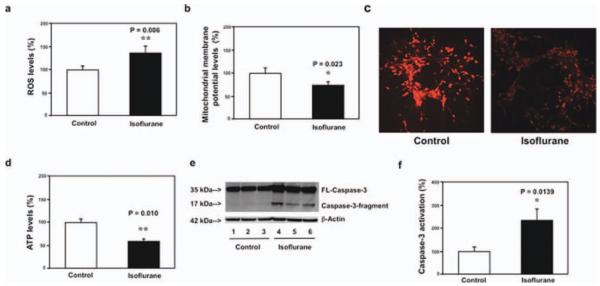

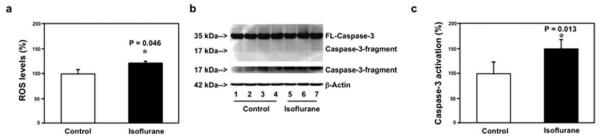

Given that hippocampus is associated with learning and memory, we determined whether isoflurane was able to induce mitochondrial dysfunction in hippocampus. We found that isoflurane increased ROS levels, reduced levels of MMP and ATP, and induced caspase 3 activation in mouse hippocampus neurons (Fig 2). Moreover, isoflurane decreased ROS levels and induced caspase 3 activation in mouse hippocampus (Fig 3). These in vivo findings further suggest that isoflurane may impair mitochondrial function in the brain regions of interest (eg, hippocampus) that are relevant to learning and memory function.

FIGURE 2.

Isoflurane increases reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels, decreases levels of mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) and adenosine-5′-triphosphate (ATP), and induces caspase 3 activation in mouse hippocampus neurons. (a) Isoflurane (black bar) increases ROS levels as compared to the control condition (white bar) in mouse hippocampus neurons. (b) Tetraethylbenzimidazolylcarbocyanine iodide fluorescence analysis shows that isoflurane (black bar) reduces levels of MMP as compared to the control condition in mouse hippocampus neurons. (v) Isoflurane may decrease levels of MMP, detected by staining of tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester and perchlorate, the MMP-dependent fluorescent indicator, as compared to the control condition in mouse hippocampus neurons. (d) Isoflurane (black bar) reduces ATP levels as compared to the control condition (white bar) in mouse hippocampus neurons. (e) Western blot shows that isoflurane (lanes 4–6) induces caspase 3 activation as compared to the control condition (lanes 1–3) in mouse hippocampus neurons. There is no significant difference in the amounts of β-actin in the control condition or the isoflurane-treated mouse hippocampus neurons. (f) Quantification of the Western blot shows that isoflurane (black bar) induces caspase 3 activation as compared to the control condition (white bar) in mouse hippocampus neurons. FL = full length.

FIGURE 3.

Isoflurane increases reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels and induces caspase 3 activation in mouse hippocampus. (a) Isoflurane (black bar) increases ROS levels as compared to the control condition (white bar) in mouse hippocampus. (b) Western blot shows that isoflurane (lanes 5–7) induces caspase 3 activation as compared to the control condition (lanes 1–4) in mouse hippocampus. There is no significant difference in amounts of β-actin in the control condition or isoflurane-treated mice. (c) Quantification of the Western blot shows that isoflurane (black bar) induces caspase 3 activation as compared to the control condition (white bar) in mouse hippocampus. FL = full length.

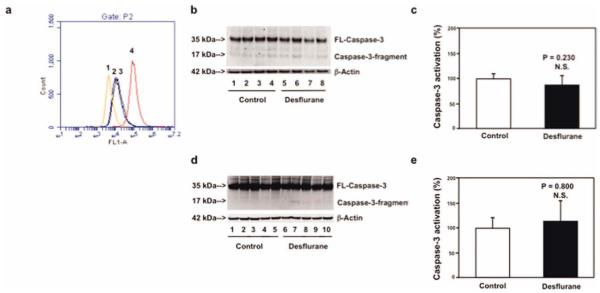

Next, we found that treatment with 12% desflurane for 3 or 6 hours induced neither opening of mPTP nor caspase 3 activation, respectively, as compared to the control condition in B104 cells (Fig 4). Furthermore, treatment with 7.5% desflurane for 6 hours did not induce caspase 3 activation in brain tissues of 6-day-old mice. Collectively, these findings from isoflurane and desflurane studies on opening of mPTP and caspase 3 activation suggest that the different effects of isoflurane and desflurane on caspase 3 activation may result from their different effects on opening of mPTP.

FIGURE 4.

Desflurane induces neither opening of mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) nor caspase 3 activation in B104 cells and mouse brain tissues. (a) Flow cytometric analysis shows changes in calcein levels in mitochondria of B104 cells stained with calcein AM or calcein AM plus cobalt, which indicates opening of mPTP: peak 1, treatment of calcein AM plus cobalt and ionomycin (positive control of opening of mPTP); peak 2, treatment of calcein AM plus cobalt and desflurane; peak 3, treatment of calcein AM plus cobalt (negative control); peak 4, treatment of calcein AM. The position of desflurane treatment (peak 2) locates away from that of positive control (peak 1) but overlaps with that of negative control (peak 3), which suggests that desflurane may not induce opening of mPTP. (b) Treatment with 12% desflurane for 6 hours (lanes 5–8) does not induce caspase 3 activation as compared to control condition (lanes 1–4) in B104 cells. There is no significant difference in amounts of β-actin in control condition or desflurane-treated B104 cells. (c) Quantification of the Western blot shows that desflurane (black bar) does not induce caspase 3 activation as compared to control condition (white bar) in B104 cells. (d) Treatment of 7.5% desflurane for 6 hours (lanes 6–10) does not induce caspase 3 activation in brain tissues of mice as compared to control condition (lanes 1–5). There is no significant difference in amounts of β-actin in control condition or desflurane-treated mouse brain tissues. (E) Quantification of the Western blot shows that desflurane (black bar) does not induce caspase 3 activation as compared to control condition (white bar) in mouse brain tissues. FL = full length; N.S. = not significant. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at annalsofneurology.org.]

Isoflurane, but Not Desflurane, Impairs Learning and Memory

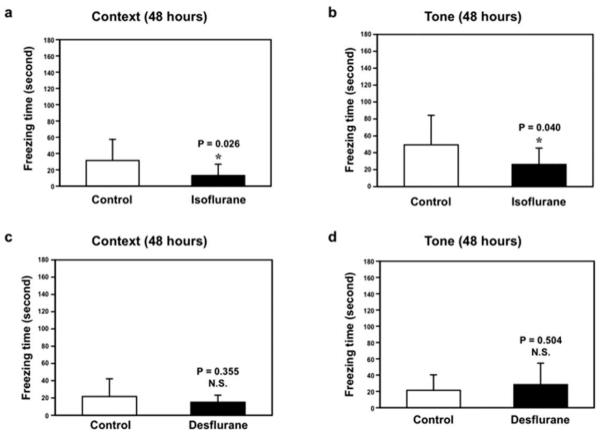

Next, we found that isoflurane anesthesia decreased freezing time in the context test (Fig 5A) and tone test (Fig 5B) of the FCT as compared to the control condition at 48 hours after the anesthesia. The isoflurance anesthesia did not significantly affect the freezing times in both the context and tone tests of the FCT in the short term (eg, 3 hours) after anesthesia (Supplementary Fig 1A and B). Furthermore, we found that anesthesia with 7.5% desflurane for 2 hours did not significantly decrease freezing times in the context and tone tests of the FCT at 3 (see Supplementary Fig 1C and D) or 48 (Fig 5C and D) hours after the anesthesia. Taken together, these findings suggest that isoflurane and desflurane may have different effects not only on opening of mPTP and cytotoxicity, but also on function of learning and memory.

FIGURE 5.

Isoflurane, but not desflurane, induces learning and memory impairment in mice. (a) Isoflurane (black bar) decreases freezing time in the context test of the fear conditioning test (FCT) as compared to control condition (white bar) at 48 hours after isoflurane treatment. (b) Isoflurane (black bar) decreases freezing time in the tone test of the FCT as compared to control condition (white bar) at 48 hours after isoflurane anesthesia. Desflurane does not decrease freezing time in the (c) context test and (D) tone test of the FCT at 48 hours after desflurane anesthesia. N.S. = not significant.

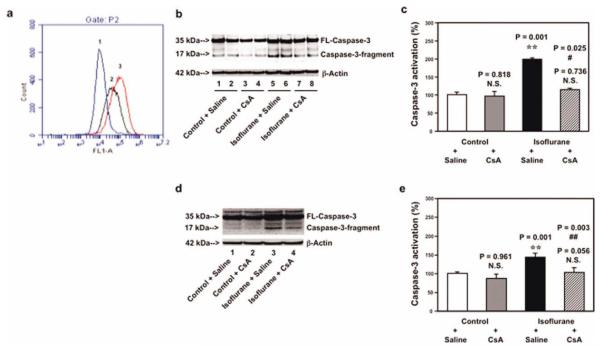

CsA Inhibits isoflurane-Induced Opening of mPTP, Caspase 3 Activation, and Impairment of Learning and Memory

CsA, a blocker of mPTP opening, has been reported to protect against stroke and to improve learning and memory.23,26,28–31 Flow cytometric analysis of calcein AM and cobalt showed that treatment with 1μM CsA (Fig 6A, peak 3) resulted in a reduction of isoflurane-induced mPTP opening (peak 2), whereas CsA treatment alone did not affect the opening of mPTP in B104 cells (data not shown). Next, we found that 1μM CsA attenuated the isoflurane-induced caspase 3 activation in B104 cells, and that 10mg/kg CsA attenuated isoflurane-induced caspase 3 activation in brain tissues of 6-day-old mice (see Fig 6).

FIGURE 6.

Cyclosporine A (CsA) attenuates isoflurane-induced opening of mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP), caspase 3 activation in B104 cells and brain tissues of mice. (a) Flow cytometric analysis shows changes in calcein levels in mitochondria of B104 cells stained with calcein AM or calcein AM plus cobalt, which indicates opening of mPTP: peak 1, treatment of ionomycin (the positive control of opening of mPTP); peak 2, treatment of isoflurane; peak 3, treatment of isoflurane plus CsA (1μM). CsA treatment attenuates isoflurane-induced opening of mPTP, as demonstrated by the position of peak of isoflurane treatment shifting to the right following CsA treatment. (b) Western blot shows that treatment of 2% isoflurane for 6 hours (lanes 5 and 6) induces caspase 3 activation as compared to control condition (lanes 1 and 2) in B104 cells. CsA treatment alone (lanes 3 and 4) does not induce caspase 3 activation as compared to control condition (lanes 1 and 2), but CsA treatment attenuates isoflurane-induced caspase 3 activation (lanes 7 and 8) as compared to isoflurane treatment (lanes 5 and 6). (c) Quantification of the Western blot shows that isoflurane (black bar) induces caspase 3 activation as compared to control condition (white bar). CsA treatment (net bar) attenuates isoflurane-induced caspase 3 activation as compared to isoflurane treatment (black bar) in B104 cells. (d) Western blot shows that treatment of 1.4% isoflurane for 6 hours (lane 3) induces caspase 3 activation as compared to control condition (lane 1). CsA treatment alone (lane 2) does not induce caspase 3 activation as compared to control condition (lane 1), but CsA treatment attenuates isoflurane-induced caspase 3 activation (lane 4) as compared to isoflurane treatment (lane 3). (e) Quantification of the Western blot shows that isoflurane (black bar) induces caspase 3 activation as compared to control condition (white bar). CsA treatment (net bar) attenuates isoflurane-induced caspase 3 activation as compared to isoflurane treatment (black bar) in mouse brain tissues. FL = full length; N.S. = not significant. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at annalsofneurology.org.]

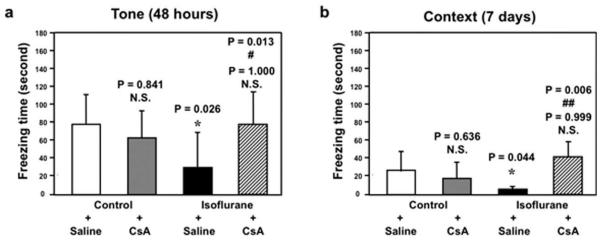

Finally, 2-way ANOVA illustrated that CsA was able to attenuate isoflurane-induced reduction of freezing time in the tone test of the FCT at 48 hours after anesthesia (Fig 7A) and reduction of freezing time in the context test of the FCT at 7 days after anesthesia (see Fig 7B), but not in other time intervals (Supplementary Fig 2). Taken together, these findings show that CsA, a blocker of mPTP, may mitigate isoflurane-induced opening of mPTP, caspase 3 activation, and impairment of learning and memory.

FIGURE 7.

Cyclosporine A (CsA) attenuates isoflurane-induced learning and memory impairment in mice. (a) Isoflurane treatment (black bar) decreases freezing time in the tone test of the fear conditioning test (FCT) as compared to control condition (white bar) at 48 hours after isoflurane anesthesia. CsA treatment alone (gray bar) does not significantly affect freezing time as compared to control condition (white bar) in the tone test of the FCT at 48 hours after the treatment. However, 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) shows that there is an interaction of CsA and isoflurane in that CsA treatment (net bar) attenuates isoflurane-induced reduction in freezing time in the tone test of the FCT at 48 hours after the treatment. (b) Isoflurane treatment (black bar) decreases freezing time in the context test of the FCT as compared to control condition (white bar) at 7 days after isoflurane anesthesia. CsA treatment alone (gray bar) does not significantly affect freezing time as compared to control condition (white bar) in the context test of the FCT at 7 days after the treatment. However, 2-way ANOVA shows that there is an interaction of CsA and isoflurane in that CsA treatment (net bar) attenuates isoflurane-induced reduction in freezing time in the context test of the FCT at 7 days after the treatment. N.S. = not significant.

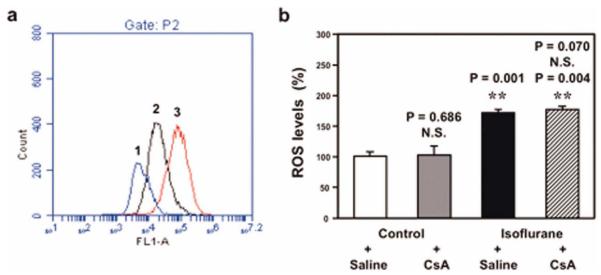

Isoflurane-Induced Opening of mPTP Is Dependent on ROS Generation

Immunocytochemistry staining of calcein AM and cobalt showed that treatment with NAC, an inhibitor of ROS generation, attenuated isoflurane-induced opening of mPTP (Fig 8A). However, CsA, a blocker of mPTP opening, did not attenuate isoflurane-induced increases in ROS levels (see Fig 8B). These findings, together with those of other studies,17–19,21–25 suggest that isoflurane-induced opening of mPTP is dependent on the effect of isoflurane to induce ROS accumulation, whereas isoflurane-induced ROS generation may be independent of and precede isoflurane-induced opening of mPTP.

FIGURE 8.

Effects of N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) and cyclosporine A (CsA) on isoflurane-induced opening of mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) and increases in reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels. (a) Flow cytometric analysis shows changes in calcein levels in mitochondria of B104 cells stained with calcein AM or calcein AM plus cobalt, which indicates opening of mPTP: peak 1, treatment of ionomycin (positive control of opening of mPTP); peak 2, isoflurane treatment; peak 3, treatment of isoflurane plus NAC (1mM), the inhibitor of ROS generation. NAC treatment attenuates isoflurane-induced opening of mPTP, as demonstrated by the position of the peak of isoflurane treatment shifting to the right following NAC treatment in B104 cells. (b) Isoflurane treatment (black bar) increases ROS levels as compared to control condition (white bar) in H4-APP cells. CsA treatment alone (gray bar) does not decrease ROS levels as compared to control condition (white bar); 2-way analysis of variance shows that there is no interaction of isoflurane and CsA on ROS levels in that CsA treatment (net bar) does not attenuate isoflurane-induced increases of ROS levels. N.S. = not significant. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at annalsofneurology.org.]

Discussion

We have found that isoflurane, but not desflurane, may induce mitochondrial dysfunction in H4-APP cells, B104 cells, mouse hippocampus neurons, and mouse hippocampus, and impair learning and memory in mice. Given that mitochondrial dysfunction is associated with cognitive dysfunction and AD associated dementia, and that hippocampus is among the brain regions relevant to learning and memory,34,35 these results suggest that isoflurane may impair learning and memory by inducing mitochondrial dysfunction.

Specifically, isoflurane, but not desflurane, induces opening of mPTP and caspase 3 activation, and CsA, a blocker of mPTP opening,22,26–31 can attenuate isoflurane-induced opening of mPTP and caspase 3 activation in vitro (B104 cells) and in the brain tissues of mice. These results suggest that isoflurane-induced opening of mPTP could be among the underlying mechanisms by which isoflurane induces caspase 3 activation and cytotoxicity. Moreover, these findings suggest that different effects of isoflurane and desflurane on opening of mPTP and mitochondrial function may explain why isoflurane, but not desflurane, can induce caspase activation and apoptosis. Note that treatment with 2% isoflurane for a short duration (eg, 3 hours) induces opening of mPTP and reduction of ATP without caspase 3 activation and cell death, whereas treatment with 2% isoflurane for a long duration (eg, 6 hours) induces caspase 3 activation and cell death.11 These results suggest that isoflurane-induced mitochondrial dysfunction may precede isoflurane-induced cytotoxicity.

Consistent with the findings that isoflurane, but not desflurane, induces mitochondrial dysfunction and cytotoxicity, we have further found that isoflurane, but not desflurane, can impair learning and memory function in mice. The mPTP opening blocker CsA can mitigate the isoflurane-induced impairment of learning and memory. These results, together with findings that desflurane anesthesia may lead to a lesser degree of cognitive decline in humans than isoflurance anesthesia,36 suggest that desflurane could be a better choice of anesthetic than isoflurane for AD patients who are susceptible to development of cognitive function decline, pending further human studies. Furthermore, these findings suggest that mitochondrial function (eg, opening of mPTP) could be among the molecular mechanisms responsible for different effects of isoflurane and desflurane on function of learning and memory.

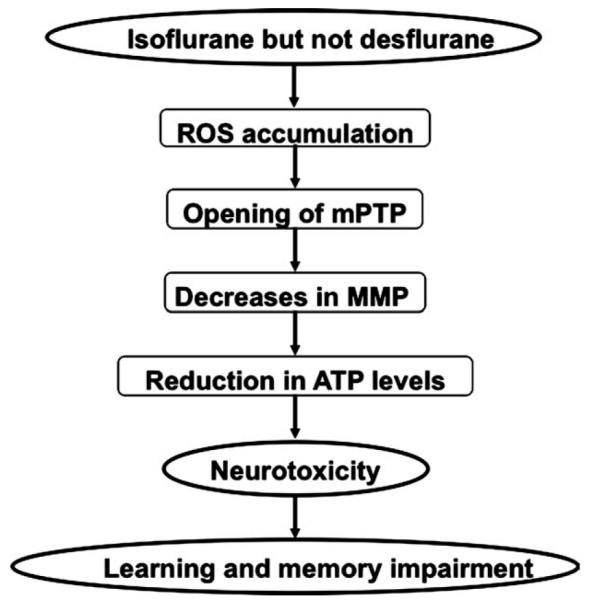

Opening of mPTP has been shown to lead to caspase activation and apoptosis by causing decreases in levels of MMP and ATP.16–18 Consistently, we have found that isoflurane can decrease levels of MMP and ATP. Moreover, the ROS generation inhibitor NAC attenuates isoflurane-induced opening of mPTP, whereas opening of mPTP blocker CsA does not mitigate isoflurane-induced ROS generation, suggesting that isoflurane may induce opening of mPTP through increasing levels of ROS. Collectively, these findings suggest a potential pathway of isoflurane-induced cytotoxicity as described in Figure 9: isoflurane increases ROS generation, which induces opening of mPTP; opening of mPTP then decreases levels of MMP and ATP, leading to neurotoxicity (eg, caspase 3 activation) and finally learning and memory impairment.

FIGURE 9.

Hypothetical pathway by which isoflurane induces cytotoxicity. Isoflurane, but not desflurane, induces reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation, which then facilitates opening of mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP). Opening of mPTP will cause decreases in levels of mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP), and consequently reduction in adenosine-5′-triphosphate (ATP) levels, leading to neurotoxicity (eg, caspase 3 activation) and finally impairment of learning and memory.

Sedlic et al37 have shown that isoflurane may delay ROS-induced opening of mPTP to produce a cytoprotection effect. It is not totally clear why current findings show that isoflurane may induce opening of mPTP, rather than delay opening of mPTP. The isoflurane treatment in studies by Sedlic et al was about 2% isoflurane for only 20 minutes, whereas isoflurane treatment in our current studies was 2% for 3 or 6 hours. Isoflurane has been shown to cause dose- and duration-dependent dual effects on caspase 3 activation (protection or potentiation).38,39 Thus, it is possible that isoflurane may induce similar dual effects on mitochondrial function (eg, mPTP opening), learning, and memory. Future studies may include a systematic investigation of the effects of isoflurane and other anesthetics (eg, desflurane, sevoflurane, and propofol) on opening of mPTP, levels of MMP, ATP, and ROS, and learning and memory function to further test this hypothesis.

The FCT is a behavioral procedure that is designed to test associative learning and memory, first demonstrated by Ivan Pavlov in 1927.40 Although no animal behavior studies can be directly applied to human learning and memory, the FCT is among the most commonly used behavioral tests to detect learning and memory impairment induced by anesthesia.33,41 The findings in the current study that isoflurane can decrease freezing time in both the context and tone tests of the FCT suggest that isoflurane may impair both hippocampus-dependent and hippocampus-independent impairment of learning and memory, which is consistent with the findings described by Saab et al.33 Note that CsA crosses the blood–brain barrier (BBB) only after damage to the brain (eg, traumatic brain injury).18,42–44 Isoflurane has been shown to induce opening of the BBB.45 Thus, it is possible that CsA may inhibit isoflurane-induced neurotoxicity and neurobehavioral deficits by entering the brain through isoflurane-induced opening of the BBB.

The underlying mechanism of different effects of isoflurane and desflurane on opening of mPTP is unknown. We have reported that isoflurane, but not desflurane, can increase ROS generation,15 and ROS may induce opening of mPTP.16–18 Thus, different effects of isoflurane and desflurane on opening of mPTP could be due to different effects of isoflurane and desflurane on ROS generation. Alternatively, desflurane, fluorinated methyl ethyl ether, differs from isoflurane only by substitution of fluorine for the chlorine found on the alpha-ethyl component of isoflurane. This change in structure could make desflurane less aggressive than isoflurane in interacting with other molecules,46 including voltage-dependent anion channel, adenine nucleotide translocase, and cyclophilin D, the components of mPTP.16–18 Therefore, desflurane may cause a lesser degree of mPTP opening as compared to isoflurane. More studies are needed to test this hypothesis by determining the interaction of isoflurane or desflurane with voltage-dependent anion channel, adenine nucleotide translocase, and cyclophilin D.

Continuous mitochondrial recycling occurs in cells, maintaining mitochondrial function.47 The half-life of mitochondria varies with tissue type in mammals, and the half-life of neuronal mitochondria is about 1 month.48 Therefore, it is unlikely that isoflurane will make permanent damages to all mitochondria. However, the isoflurane-induced transient damage of mitochondria could lead to detrimental effects, which are largely unknown and warrant further studies.

This study has a few limitations. First, mPTP opening has not been confirmed to be associated with learning and memory function; thus, the effects of isoflurane on mPTP opening and isoflurane-induced learning and memory impairment may both be true, but may not be causally related. The results from the current study show that CsA can inhibit isoflurane-induced mPTP opening, caspase 3 activation, and impairment of learning and memory. These findings suggest for the first time that isoflurane-induced mPTP opening may be associated with isoflurane-induced neurotoxicity and impairment of learning and memory, and more studies are needed to further test this hypothesis. Second, we only tested effects of isoflurane and desflurane on associative learning and memory in mice by using the FCT. Isoflurane and desflurane may have different effects on other kinds of learning and memory (eg, spatial learning and memory). However, the findings that isoflurane, but not desflurane, impairs associative learning and memory, and induces opening of mPTP and mitochondrial dysfunction, and that mPTP blocker CsA can mitigate these isoflurane-induced detrimental effects, suggest that the different effects of isoflurane and desflurane on learning and memory may result from the different effects of isoflurane and desflurane on mitochondrial function. Third, we only measured caspase 3 activation in the current study. This is because our previous studies have already shown that isoflurane can induce caspase 3 activation, apoptosis, Aβ accumulation, and neuroinflammation.7–9,49 In addition, a recent study by Burguillos et al50 has shown that caspase activation alone without apoptosis may still be able to contribute to AD neuropathogenesis.

In conclusion, we have found that the commonly used inhalation anesthetic isoflurane, but not desflurane, can increase ROS levels, induce opening of mPTP, reduce levels of MMP and ATP, cause caspase 3 activation, and impair learning and memory in vitro and in vivo. Furthermore, we have found that isoflurane may induce opening of mPTP through increasing ROS levels. Finally, CsA, a blocker of mPTP opening, can attenuate these isoflurane-induced detrimental effects. These findings should promote more studies to identify anesthetic(s) that will not enhance or will enhance to a lesser degree AD neuropathogenesis and decline of cognitive function, and to investigate underlying mechanisms. Ultimately, these studies, through the combined efforts of researchers in anesthesia and neurology, may develop guidelines on to how to provide safer anesthesia care for AD patients (eg, to avoid worsening of AD neuropathogenesis and decline of cognitive function by anesthesia and surgery), like those developed through the combined efforts of researchers in anesthesia and cardiology regarding safer anesthetic care for coronary artery disease patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by NIH grants K08 NS048140, (NINDS), R21 AG029856 (NIA), and R01 GM088801 (NINDS) (Z. Xie); American Geriatrics Society Jahnigen Award (Z. Xie); an Investigator-Initiated Research Grant from Alzheimer’s Association (Z. Xie); Cure Alzheimer’s Fund (Z. Xie); and NIH grant DK082427 (NIDDK) (H.S.). The Department of Anesthesia, Critical Care, and Pain Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School covered the cost of inhalation anesthetic isoflurane and desflurane. The work was performed at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Charlestown, Massachusetts. The flow cytometric analysis was performed at the Cell Biology Core of Harvard Clinic Nutrition Research Center [NIH grant P30 DK040561 (NIDDK) to Dr. Allan Walker].

We thank Drs G. Johnson and C. Ran for constructive discussion; Drs D. Kovacs and D. Kim for generously providing the B104 cells; and Dr H. Zheng for advice regarding statistical analysis of the data.

Potential Conflicts of Interest D.J.C.: board membership, American Board of Anesthesiology. G.C.: grants/grants pending, NIH; travel expenses, Emory University, American Board of Anesthesiology.

Footnotes

Additional supporting information can be found in the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Alzheimer’s Association . Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimer’s Association; Chicago, IL: 2011. http://www.alz.org/downloads/Facts_Figures_2011.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silbert B, Evered L, Scott DA, Maruff P. Anesthesiology must play a greater role in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Anesth Analg. 2011;112:1242–1245. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182147f5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bittner EA, Yue Y, Xie Z. Brief review: anesthetic neurotoxicity in the elderly, cognitive dysfunction and Alzheimer’s disease. Can J Anaesth. 2011;58:216–223. doi: 10.1007/s12630-010-9418-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baranov D, Bickler PE, Crosby GJ, et al. Consensus statement: First International Workshop on Anesthetics and Alzheimer’s disease. Anesth Analg. 2009;108:1627–1630. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318199dc72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eckenhoff RG, Johansson JS, Wei H, et al. Inhaled anesthetic enhancement of amyloid-beta oligomerization and cytotoxicity. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:703–709. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200409000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brambrink AM, Evers AS, Avidan MS, et al. Isoflurane-induced neuroapoptosis in the neonatal rhesus macaque brain. Anesthesiology. 2010;112:834–841. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181d049cd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xie Z, Culley DJ, Dong Y, et al. The common inhalation anesthetic isoflurane induces caspase activation and increases amyloid beta-protein level in vivo. Ann Neurol. 2008;64:618–627. doi: 10.1002/ana.21548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xie Z, Dong Y, Maeda U, et al. The common inhalation anesthetic isoflurane induces apoptosis and increases amyloid beta protein levels. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:988–994. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200605000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xie Z, Dong Y, Maeda U, et al. The inhalation anesthetic isoflurane induces a vicious cycle of apoptosis and amyloid beta-protein accumulation. J Neurosci. 2007;27:1247–1254. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5320-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xie Z, Dong Y, Maeda U, et al. Isoflurane-induced apoptosis: a potential pathogenic link between delirium and dementia. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:1300–1306. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.12.1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wei H, Kang B, Wei W, et al. Isoflurane and sevoflurane affect cell survival and BCL-2/BAX ratio differently. Brain Res. 2005;1037:139–147. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loop T, Dovi-Akue D, Frick M, et al. Volatile anesthetics induce caspase-dependent, mitochondria-mediated apoptosis in human T lymphocytes in vitro. Anesthesiology. 2005;102:1147–1157. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200506000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wei H, Liang G, Yang H, et al. The common inhalational anesthetic isoflurane induces apoptosis via activation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors. Anesthesiology. 2008;108:251–260. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000299435.59242.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang B, Dong Y, Zhang G, et al. The inhalation anesthetic desflurane induces caspase activation and increases amyloid beta-protein levels under hypoxic conditions. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:11866–11875. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800199200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y, Dong Y, Wu X, et al. The mitochondrial pathway of anesthetic isoflurane-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:4025–4037. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.065664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fulda S, Galluzzi L, Kroemer G. Targeting mitochondria for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:447–464. doi: 10.1038/nrd3137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kroemer G, Galluzzi L, Brenner C. Mitochondrial membrane permeabilization in cell death. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:99–163. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sullivan PG, Rabchevsky AG, Waldmeier PC, Springer JE. Mitochondrial permeability transition in CNS trauma: cause or effect of neuronal cell death? J Neurosci Res. 2005;79:231–239. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitchell P, Moyle J. Stoichiometry of proton translocation through the respiratory chain and adenosine triphosphatase systems of rat liver mitochondria. Nature. 1965;208:147–151. doi: 10.1038/208147a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernardi P, Broekemeier KM, Pfeiffer DR. Recent progress on regulation of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore; a cyclosporin-sensitive pore in the inner mitochondrial membrane. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1994;26:509–517. doi: 10.1007/BF00762735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bernardi P. The permeability transition pore. Control points of a cyclosporin A-sensitive mitochondrial channel involved in cell death. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1275:5–9. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(96)00041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nicolli A, Basso E, Petronilli V, et al. Interactions of cyclophilin with the mitochondrial inner membrane and regulation of the permeability transition pore, and cyclosporin A-sensitive channel. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:2185–2192. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.4.2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marchetti P, Castedo M, Susin SA, et al. Mitochondrial permeability transition is a central coordinating event of apoptosis. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1155–1160. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zamzami N, Larochette N, Kroemer G. Mitochondrial permeability transition in apoptosis and necrosis. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12(suppl 2):1478–1480. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fournier N, Ducet G, Crevat A. Action of cyclosporine on mitochondrial calcium fluxes. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1987;19:297–303. doi: 10.1007/BF00762419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hansson MJ, Mansson R, Mattiasson G, et al. Brain-derived respiring mitochondria exhibit homogeneous, complete and cyclosporin-sensitive permeability transition. J Neurochem. 2004;89:715–729. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.He L, Lemasters JJ. Regulated and unregulated mitochondrial permeability transition pores: a new paradigm of pore structure and function? FEBS Lett. 2002;512:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03314-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Norman KG, Canter JA, Shi M, et al. Cyclosporine A suppresses keratinocyte cell death through MPTP inhibition in a model for skin cancer in organ transplant recipients. Mitochondrion. 2010;10:94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alessandri B, Rice AC, Levasseur J, et al. Cyclosporin A improves brain tissue oxygen consumption and learning/memory performance after lateral fluid percussion injury in rats. J Neurotrauma. 2002;19:829–841. doi: 10.1089/08977150260190429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Osman MM, Lulic D, Glover L, et al. Cyclosporine-A as a neuro-protective agent against stroke: its translation from laboratory research to clinical application. Neuropeptides. 2011;45:359–368. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu Y, Wu X, Dong Y, et al. Anesthetic sevoflurane causes neurotoxicity differently in neonatal naive and Alzheimer disease transgenic mice. Anesthesiology. 2010;112:1404–1416. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181d94de1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Y, Zhen Y, Dong Y, et al. Anesthetic propofol attenuates the isoflurane-induced caspase-3 activation and Aβ oligomerization. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27019. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saab BJ, Maclean AJ, Kanisek M, et al. Short-term memory impairment after isoflurane in mice is prevented by the α5 γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor inverse agonist L-655,708. Anesthesiology. 2010;113:1061–1071. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181f56228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reddy PH, Tripathi R, Troung Q, et al. Abnormal mitochondrial dynamics and synaptic degeneration as early events in Alzheimer’s disease: implications to mitochondria-targeted antioxidant therapeutics. Biochim Biophys Acta. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.10.011. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Querfurth HW, LaFerla FM. Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:329–344. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0909142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang B, Tian M, Zhen Y, et al. The effects of isoflurane and desflurane on cognitive function in humans. Anesth Analg. 2012;114:410–415. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31823b2602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sedlic F, Sepac A, Pravdic D, et al. Mitochondrial depolarization underlies delay in permeability transition by preconditioning with isoflurane: roles of ROS and Ca2+ Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;299:C506–C515. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00006.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu Z, Dong Y, Wu X, et al. The potential dual effects of anesthetic isoflurance on Abeta induced apoptosis. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2011;8:741–752. doi: 10.2174/156720511797633223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pan C, Xu Z, Dong Y, et al. The potential dual effects of anesthetic isoflurance on hypoxia-induced caspase-3 activation and increases in beta-site amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme levels. Anesth Analg. 2011;113:145–152. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182185fee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pavlov IP. Conditional reflexes. Dover Publications; New York, NY: 1927/1960. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Satomoto M, Satoh Y, Terui K, et al. Neonatal exposure to sevoflurane induces abnormal social behaviors and deficits in fear conditioning in mice. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:628–637. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181974fa2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shiga Y, Onodera H, Matsuo Y, Kogure K. Cyclosporin A protects against ischemia-reperfusion injury in the brain. Brain Res. 1992;595:145–148. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91465-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Uchino H, Elmer E, Uchino K, et al. Cyclosporin A dramatically ameliorates CA1 hippocampal damage following transient fore-brain ischaemia in the rat. Acta Physiol Scand. 1995;155:469–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1995.tb09999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Uchino H, Elmer E, Uchino K, et al. Amelioration by cyclosporin A of brain damage in transient forebrain ischemia in the rat. Brain Res. 1998;812:216–226. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00902-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tetrault S, Chever O, Sik A, Amzica F. Opening of the blood-brain barrier during isoflurane anaesthesia. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;28:1330–1341. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang L, Liu JY, Wan SQ, Li ZS. Theoretical studies of the reactions of CF3CHCLOCHF2/CF3CHFOCHF2 with OH radical and Cl atom and their product radicals with OH. J Comput Chem. 2009;30:565–580. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chang DT, Reynolds IJ. Mitochondrial trafficking and morphology in healthy and injured neurons. Prog Neurobiol. 2006;80:241–268. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reddy PH. Role of mitochondria in neurodegenerative diseases: mitochondria as a therapeutic target in Alzheimer’s disease. CNS Spectr. 2009;14(8 suppl 7):8–13. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900024901. discussion 16–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu X, Lu Y, Dong Y, et al. The inhalation anesthetic isoflurane increases levels of proinflammatory TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β. Neurobiol Aging. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.11.002. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burguillos MA, Deierborg T, Kavanagh E, et al. Caspase signalling controls microglia activation and neurotoxicity. Nature. 2011;472:319–324. doi: 10.1038/nature09788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.