Abstract

Background

An increasing number of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) patients are combating HIV infection through antiretroviral drugs including reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Oral complications associated with these drugs are becoming a mounting concern. In our previous studies, both protease inhibitors and reverse transcriptase inhibitors have been shown to change the proliferation and differentiation state of oral tissues. This study examines the effect of a non-nucleoside and a nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor on the growth and differentiation of gingival epithelium.

Methods

Organotypic (raft) cultures of gingival keratinocytes were treated with a range of Efavirenz and Tenofovir concentrations. Raft cultures were immunohistochemically analyzed to determine the effect of these drugs on the expression of key differentiation and proliferation markers including cytokeratins and PCNA.

Results

These drugs dramatically changed the proliferation and differentiation state of gingival tissues when they were present throughout the growth period of the raft tissue as well as when drugs were added to established tissue on day 8. Drugs treatment increased the expression of cytokeratin 10 and PCNA, and conversely, decreased expression of cytokeratins 5, involucrin and cytokeratin 6. Gingival tissue exhibited increased proliferation in the suprabasal layers, increased fragility, and an inability to heal itself.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that Efavirenz and Tenofovir treatments, even when applied in low concentrations for short periods of time, deregulated the cell cycle/proliferation and differentiation pathways, resulting in abnormal epithelial repair and proliferation. Our system could be developed as a potential model for studying HIV/ highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) affects in vitro.

Keywords: antiretroviral therapy, cytokeratins, HIV infections, efavirenz, tenofovir, oral complications

Introduction

The advent of antiretroviral drugs has greatly decreased the mortality and improved life expectancy of HIV patients. With the use of these drugs, HIV patients can live long lives with suppressed immune systems. However, oral complications are the most common manifestations in HIV patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) drug regimens. The usual HAART regimen combines three or more different drugs such as two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) and a protease inhibitor (PI), two NRTIs and a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) or other such combinations. These HAART regimens have been shown to reduce the viral load in patients. By contrast, HAART has been shown to have several oral complications such as: oral warts (1, 2), erythema multiforme (3, 4), xerostomia (3, 4), toxic epidermal necrolysis, lichenoid reactions (4, 5), exfoliative cheilitis(3), oral ulceration and paraesthesia (3, 6). These complications affect both quality of life in patients and noncompliance in drug regimens.

Efavirenz (trade name Sustiva) is a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI), which is often used in HAART treatment. Tenofovir (trade name Viread), also an important component of HAART, is a nucleoside analog reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI). Previous studies have examined the effect of both protease inhibitors and a nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor of gingival tissue (7, 8). This study seeks to expand on those results by comparing the effects of both nucleoside and non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors on gingival tissue.

Materials and Methods

Primary gingival keratinocytes and organotypic raft cultures

Primary gingival keratinocytes were isolated from a mixed pool of tissues obtained from patients undergoing dental surgery (9) in accordance with Penn State University College of Medicine Institutional review Board (IRB# 25284) procedures. The tissue was processed as described before (9).

Raft cultures were grown as previously described (10, 11). Rafts were fed with E-media supplemented with either Efavirenz or Tenofovir. Efavirenz capsules (Bristol-Myers Squibb Company) and Tenofovir capsules (Gilead Sciences) were purchased from the Pharmacy at The Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, Penn State University. The contents of either a 200 mg or 300 mg capsule was removed and resuspended in sterile PBS. Serial dilutions were made directly in E-media to reach the correct concentration. The Cmax of Efavirenz is 4μg/mL (12–14). In the first set of experiments, the rafts were treated with Efavirenz at concentrations of 1, 2, 4, 5, and 7 μg/mL from day 0. Control rafts were fed with E-media only. Additional experiments were performed using the same concentrations of Efavirenz but beginning treatment of the raft cultures on day 8. All rafts were fed every other day and harvested at the indicated time points. The Cmax of Tenofovir is 362 ng/mL (12–14). The rafts were treated with Tenofovir at concentrations of 200, 250, 362, 400, and 600 ng/mL from day 0 or day 8 as described above.

Histochemical analyses

Raft cultures were fixed in 10% buffered formalin, and embedded in paraffin. Four micrometer sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin as described previously (10).

Immunostaining was performed with the Vectastain Elite ABC kit (Vector laboratories Burlingame, CA, USA)(10). The slides were stained as described previously, using the following primary antibodies: mouse monoclonal keratin 5 (clone XM26; dilution 200 mg/mL), keratin 10 (clone DEK10; dilution 200 mg/mL), involucrin (200 mg/mL), keratin 6 (clone LHK6B; dilution10 ng/mL) (all from Lab Vision, Fremont, CA, USA) and rabbit polyclonal proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) (cloneFL-261; dilution 2 mg/mL(Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA)(9).

Results

Effect of Efavirenz and Tenofovir on morphological differentiation and stratification of gingival keratinocytes in raft cultures

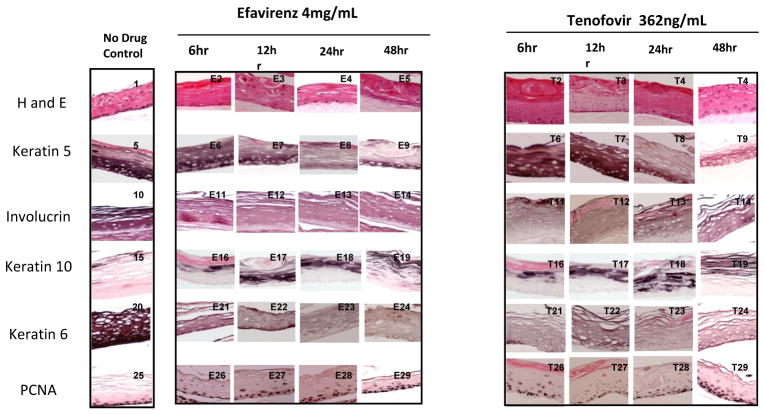

The raft culture system has been shown to accurately mimic the in vivo physiology of the gingival epidermis (7–9, 15, 16). Hematoxylin and eosin staining was performed to examine the effect of these drugs on gingival epithelial morphology and stratification. Figure 1 shows the results of both drugs after ten days of treatment (Panels E1–E6 and T1–T6). There is a dramatic change in morphology and stratification as was seen with the NTRI Zidovudine (9). Normally, nuclei are only present in the basal layer of cells, as is the case with our untreated rafts however both abnormal nuclei and keratin pearls are visible in treated tissues.

Figure One. Effect of Efavirenz and Tenofovir on gingival epithelium morphology, stratification and expression patterns of differentiation markers.

Primary gingival keratinocytes were grown in organotypic (raft) cultures and treated with different concentrations of drug. Drug treatment began at day 0 and continued for 10 days. Panels E1–E6 and T1–T6 show hematoxylin and eosin staining at the indicated drug concentrations. Panels E7–E12 and T7–T12 show Keratin five staining at the indicated drug concentration. Panels E13–E18 and T13–T18 show Involucrin staining, Panels E19–E24 and T19–T24 show Keratin 10 staining. Panels E25–E30 and T25–T30 show Keratin 6 staining and panels E31–E36 and T31–T36 show PCNA staining. Images are at 20 X original magnification.

Efavirenz and Tenofovir treatment changes the expression pattern of differentiation markers in gingival epithelium

Involucrin and the cytokeratins 5 and 10 are associated with the terminal differentiation of gingival epithelium (17). Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was used to assess the expression pattern of biochemical markers of differentiation in treated and untreated samples.

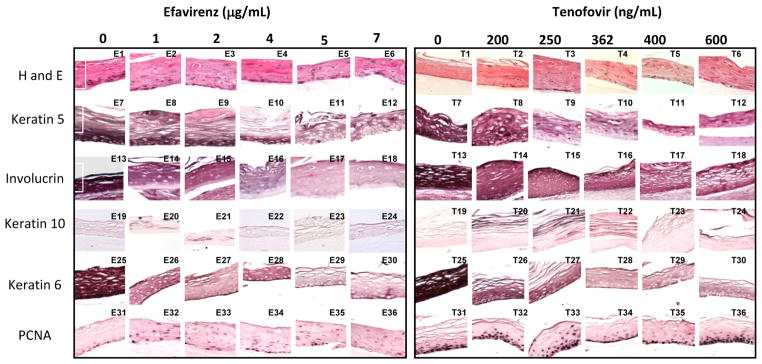

Cytokeratin 5 and its partner cytokeratin 14 form dimers that help give tissue its integrity. Both drug treatments decreased and changed the expression pattern of cytokeratin 5 at all drug concentrations beginning with tissue harvested at day 8 (Figure 1 Panels E7–E12 and T7–T12 and data not shown). Tissues that were grown to day eight and then drug exposed were also affected even if they were only drug-exposed for 6 hours (Figure 2 Panels E6–E9 and T9–T12). It is apparent that RTIs reduce the amount of this cytokeratin in gingival tissue.

Figure 2. Effect of Efavirenz and Tenofovir on gingival epithelium morphology, stratification and cytokeratin expression pattern in established gingival raft cultures.

Primary gingival keratinocytes were grown in organotypic (raft) cultures to day eight without drug treatment. On day eight the indicated amount of drug was added. The tissue was then harvested 6, 12, 24 or 48 hours later. Panels 1, 5, 10, 15, 20 and 25 are untreated rafts. Panels E2–E5 and T2–T5 show hematoxylin and eosin staining at the indicated drug concentrations. Panels E6–E9 and T6–T9 show Keratin five staining at the indicated drug concentration. Panels E10–E14 and T10–T14 show Involucrin staining, Panels E16–E19 and T16–T19 show Keratin 10 staining. Panels E20–E24 and T20–T24 show Keratin 6 staining and panels E26–E29 and T26–T29 show PCNA staining. Images are at 20 X original magnification.

Involucrin is expressed in response to the same pathway as cytokeratin 5 and is present in keratinocytes in epidermis and other stratified squamous epithelia. Efavirenz and Tenofovir both decreased the expression pattern of involucrin at all drug concentrations and at all time points (Figure 1 Panels E13–E18 and T13–T18, and Figure 2 Panels E11–E14 and T11–T14).

Cytokeratin 10 expression indicates terminal differentiation of tissue and is usually expressed in low levels in the suprabasal layers of oral keratinocytes (18, 19). Efavirenz and Tenofovir treatments both induced the expression of cytokeratin 10 and changed its expression pattern, though the effect of Tenofovir was more dramatic, small increases could be seen as early as 6 hours but more tissue wide changes were evident at 48 hours. (Figure 1 Panels E16–E24 and T16–T24). These results are similar to those seen in Zidovudine treated rafts (9).

Effects of Efavirenz and Tenofovir treatment on the expression of keratin 6

Cytokeratin 6 expression is related with the wound healing process and is expressed in the suprabasal layer. Epidermal injury results in induced cytokeratin 6 expression in keratinocytes undergoing activation at the wounded edge (20, 21). In our study, cytokeratin 6 expression was dramatically reduced at all concentrations of both drugs. A noticeable decrease in cytokeratin 6 was seen after just 6 hours when either drug was added to tissue after 8 days of growth (Figure 1 Panels E25–E30 and T25–T30, and Figure 2 E21–E24 and T21–T26). Such an immediate decrease in expression of cytokeratin 6 days post treatment suggests an impaired wound healing response of tissue against drug induced injury.

Efavirenz and Tenofovir treatments induce cell proliferation

We evaluated the effect of these drugs on the expression of a well-characterized cell proliferation marker, PCNA. PCNA is a nuclear protein associated with DNA polymerase delta, which is present throughout the cell cycle in the nuclei of proliferating cells. Typically, cells only proliferate in the basal layer of tissue. In this study, the PCNA expression in untreated rafts was limited to the basal layer. In drug treated rafts, however, PCNA was strongly expressed in both the basal and differentiating layers of the tissue (Figure 1, Panels E31–E36 and T31–T36). This effect on PCNA expression is seen as early as 6 to 12 hours post treatment (Figure 2 Panels E26–E29 and T26–T29). In addition, tissues in this study also showed an increase in cyclin A staining similar as to what was seen in Zidovudine treated tissues (data not shown) (9). Proliferation is most increased in Tenofovir treated rafts however; the proliferation in differentiating tissues is very evident in Efavirenz treated rafts. Around day 16–18 all drug treated rafts show a marked decline in PCNA expression (data not shown) suggesting that over time tissue becomes less proliferative due to the cytostatic effects of the drug. The changed expression pattern of PCNA indicates the activation of the wound healing pathway and that drug treated rafts have lost control of cell cycle events, which could play a role in the generation of oral complications in HIV patients.

Discussion

HIV-positive patients taking highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) have reported many oral complications, which have a major impact on their overall health and quality of life. Protease inhibitors have been shown to effect both the growth and differentiation of oral epithelium, however, the effects of non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTI) on the growth and differentiation of oral epithelium is currently unknown.

The growth of gingival epithelium was inhibited when either the drug, Efavirenz, an NNTRI or Tenofovir, an NRTI, was present throughout the growth period, even in concentrations below their Cmax. They also disrupted its proliferation and stratification status. Our observations suggest the possibility that oral epithelium in HIV patients exposed to HAART, including these drugs, experience drug induced abnormalities in the tissue’s molecular and cellular biology leading to oral complications.

Normally, gingival stratified epithelia express the cytokeratin pair of cytokeratins 5 and 14 only in the proliferative basal layer (17, 22). Application of Tenofovir and Efavirenz decreased the presence of cytokeratin 5 (Figure 1 Panels E7–E12 and T7–T12). The decrease in cytokeratin 5 was seen in all levels of the oral tissue. Cytokeratin 5 and its partner cytokeratin 14 form dimers that help give tissue its integrity. Without these cytokeratins present tissue becomes very fragile and the smallest injury causes tissue to fall apart and blisters to form (18). These cytokeratins have also been shown to be enhanced in hyperproliferative situations such as wound healing (7, 21, 23). These data suggest that RTI treatment is impairing the ability of oral tissue to heal itself.

When cells make the commitment to terminally differentiate a switch in cytokeratin gene expression occurs. Expression of cytokeratins 5 and 14 is shut off and that of cytokeratins1 and 10 is turned on (24). In this study, drug treatments induced the expression of cytokeratin 10. Increased levels of cytokeratin 10 in drug-treated gingival epithelium may be an attempt by the tissue to protect itself against damage caused by the drugs (18, 25, 26). Additionally, it has been shown that cytokeratin 10 is more strongly expressed in both oral lesions after treatment with Efavirenz and Tenofovir and hyperproliferative epidermis when compared to ordinary epidermis (27). Thus, the elevated levels of cytokeratin 10 may be linked to the proliferative effect of the drugs.

The response of tissues to Efavirenz and Tenofovir was similar to that seen with the NRTI, Zidovudine (Table 1) (9). In that case we suggested that a lack of involucrin available for cross-linking in the cornified envelope and suprabasal layers of the epidermis may explain the lack of a vacuolated, cornified layer seen in treated tissues and may account for the fragility of oral tissues in HAART patients (3). Efavirenz and Tenofovir are likely acting on cytokeratin 5 and involucrin through the Sp1 pathway (28) in a similar manner to Zidovudine (Table 1) (9).

Table 1. Summary of effects of HIV drugs on gingival raft cultures.

The table summarizes the effects of various HIV treatments on morphology and cytokeratin expression patterns in gingival raft cultures.

| Effect on Expression of: | Efavirenz | Tenofovir | Zidovudine (9) | Amprenavir (7) | Kaletra (8) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Keratin 5 | Decreases | Decreases | Decreases | Increases | Increases |

| Involucrin | Decreases | Decreases | Decreases | Not Tested | Not Tested |

| Keratin 10 | Increases | Increases | Increases | Increases | Increases |

| Keratin 6 | Decreases | Decreases | Decreases | Increases | Increases |

| PCNA | Increases | Increases | Increases | Increases | Increases |

Previous data suggests that HAART drugs cause damage to the gingival epithelium (7–9). To examine this possibility, we looked at expression patterns of cytokeratin 6, which is activated in response to injury in the suprabasal layer of stratified epithelium. In the current study, cytokeratin 6 expression was reduced significantly by all concentrations of Efavirenz and Tenofovir, at all time points examined, including just 6 hours post treatment. The inability of oral tissue, which is constantly in a wounding environment, to repair itself through the cytokeratin 6 mechanism could explain some of the oral complications seen in HAART patients.

The results of hematoxylin and eosin staining suggested a change in the proliferation status of drug treated rafts. Therefore, we examined the effect of Efavirenz and Tenofovir on PCNA. This nuclear protein plays an important role in DNA synthesis and cell cycle progression, allowing cell proliferation. PCNA is generally found in cell nuclei between the G1 and M phases of the cell cycle (31, 32). Normally, PCNA is expressed in only a few basal layer cells (33). An increased expression of PCNA in drug treated rafts was seen in this study. Not only was there increased PCNA in the basal layer of the drug treated tissue; PCNA also became apparent in the suprabasal layers of the drug treated tissue. This increased expression of PCNA could indicate the activation of wound healing pathways attempting to counteract drug induced tissue damage, a conclusion supported by the elevated levels of cytokeratin 10 in treated rafts. However, it is more likely that exposure to these drugs deregulated cell proliferation and differentiation pathways allowing abnormal proliferation independent of wound healing pathways. This argument is supported by the decrease in cytokeratin 6 in drug treated tissues. Overall, the treated tissue is highly and abnormally proliferative and has impaired epithelial repair mechanisms thus making the tissue more vulnerable to the oral complications seen in HIV patients taking this drug. The increased levels of PCNA and cytokeratin 10 indicate that the tissue is in a hyperproliferative state that may make in more conducive to the viral tumors common in HIV-positive patients. Decreased levels of cytokeratin 5 and 6 and involucrin suggest that the tissue is fragile and unable to repair itself sufficiently, adding to a permissive environment for opportunistic infections and other complications.

In conclusion, we have observed that Efavirenz and Tenofovir, like Zidovudine, can inhibit and change the growth of gingival tissue both when the drug was added at day 0 or day 8 of raft growth. These drugs increased the expression of PCNA and cytokeratin 10. Conversely the expression of cytokeratin 5 and 6 and involucrin were decreased. Together these results suggest that these RTIs deregulated the growth, differentiation and proliferation profiles in human gingival raft tissue. These results are consistent with the finding of oral complications in patients undergoing long-term HAART. Additional studies will be needed to determine the exact mechanism through which these drugs are exerting their effects.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lynn Budgeon for technical assistance in preparing histological slides. This work was supported by NIDCR grant DE018305 to Craig Meyers.

References

- 1.Hodgson TA, Greenspan D, Greenspan JS. Oral lesions of HIV disease and HAART in industrialized countries. Adv Dent Res. 2006;19:57–62. doi: 10.1177/154407370601900112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greenspan D, Canchola AJ, MacPhail LA, Cheikh B, Greenspan JS. Effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy on frequency of oral warts. Lancet. 2001;357:1411–1412. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04578-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diz Dios P, Scully C. Adverse effects of antiretroviral therapy: focus on orofacial effects. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2002;1:307–317. doi: 10.1517/14740338.1.4.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scully C, Diz Dios P. Orofacial effects of antiretroviral therapies. Oral diseases. 2001;7:205–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fagot JP, Mockenhaupt M, Bouwes-Bavinck JN, Naldi L, Viboud C, Roujeau JC. Nevirapine and the risk of Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis. Aids. 2001;15:1843–1848. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200109280-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jordan RA. Implications of antiretroviral therapy in oral medicine--a review of literature. Schweizer Monatsschrift fur Zahnmedizin = Revue mensuelle suisse d’odonto-stomatologie = Rivista mensile svizzera di odontologia e stomatologia / SSO. 2007;117:1210–1216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Israr M, Mitchell D, Alam S, Dinello D, Kishel JJ, Meyers C. Effect of the HIV protease inhibitor amprenavir on the growth and differentiation of primary gingival epithelium. Antiviral therapy. 2010;15:253–265. doi: 10.3851/IMP1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Israr M, Mitchell D, Alam S, Dinello D, Kishel JJ, Meyers C. The HIV protease inhibitor lopinavir/ritonavir (Kaletra) alters the growth, differentiation and proliferation of primary gingival epithelium. Hiv Med. 2011;12:145–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2010.00863.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitchell D, Israr M, Alam S, Kishel J, Dinello D, Meyers C. Effect of the HIV nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor zidovudine on the growth and differentiation of primary gingival epithelium. HIV Med. 2012;13:276–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2011.00973.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meyers C, Frattini MG, Hudson JB, Laimins LA. Biosynthesis of human papillomavirus from a continuous cell line upon epithelial differentiation. Science. 1992;257:971–973. doi: 10.1126/science.1323879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meyers C. Organotypic (raft) epithelial tissue culture system for the differentiation dependent replication of papillomavirus. Meth Cell Sci. 1996;18:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cressey TR, Jourdain G, Rawangban B, Varadisai S, Kongpanichkul R, Sabsanong P, Yuthavisuthi P, Chirayus S, Ngo-Giang-Huong N, Voramongkol N, Pattarakulwanich S, Lallemant M. Pharmacokinetics and virologic response of zidovudine/lopinavir/ritonavir initiated during the third trimester of pregnancy. Aids. 24:2193–2200. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833ce57d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cremieux AC, Katlama C, Gillotin C, Demarles D, Yuen GJ, Raffi F. A comparison of the steady-state pharmacokinetics and safety of abacavir, lamivudine, and zidovudine taken as a triple combination tablet and as abacavir plus a lamivudine-zidovudine double combination tablet by HIV-1-infected adults. Pharmacotherapy. 2001;21:424–430. doi: 10.1592/phco.21.5.424.34497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Unadkat JD, Collier AC, Crosby SS, Cummings D, Opheim KE, Corey L. Pharmacokinetics of oral zidovudine (azidothymidine) in patients with AIDS when administered with and without a high-fat meal. Aids. 1990;4:229–232. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199003000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klausner M, Ayehunie S, Breyfogle BA, Wertz PW, Bacca L, Kubilus J. Organotypic human oral tissue models for toxicological studies. Toxicol In Vitro. 2007;21:938–949. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2007.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tomakidi P, Fusenig NE, Kohl A, Komposch G. Histomorphological and biochemical differentiation capacity in organotypic co-cultures of primary gingival cells. J Periodontal Res. 1997;32:388–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1997.tb00549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mackenzie IC, Rittman G, Gao Z, Leigh I, Lane EB. Patterns of cytokeratin expression in human gingival epithelia. J Periodontal Res. 1991;26:468–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1991.tb01797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonan PR, Kaminagakura E, Pires FR, Vargas PA, Almeida OP. Cytokeratin expression in initial oral mucositis of head and neck irradiated patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:205–211. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eichner R, Bonitz P, Sun TT. Classification of epidermal keratins according to their immunoreactivity, isoelectric point, and mode of expression. J Cell Biol. 1984;98:1388–1396. doi: 10.1083/jcb.98.4.1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paladini RD, Takahashi K, Bravo NS, Coulombe PA. Onset of re-epithelialization after skin injury correlates with a reorganization of keratin filaments in wound edge keratinocytes: defining a potential role for keratin 16. J Cell Biol. 1996;132:381–397. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.3.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weiss RA, Eichner R, Sun TT. Monoclonal antibody analysis of keratin expression in epidermal diseases: a 48- and 56-kdalton keratin as molecular markers for hyperproliferative keratinocytes. J Cell Biol. 1984;98:1397–1406. doi: 10.1083/jcb.98.4.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Purkis PE, Steel JB, Mackenzie IC, Nathrath WB, Leigh IM, Lane EB. Antibody markers of basal cells in complex epithelia. J Cell Sci. 1990;97(Pt 1):39–50. doi: 10.1242/jcs.97.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bernerd F, Magnaldo T, Darmon M. Delayed onset of epidermal differentiation in psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 1992;98:902–910. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12460344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fuchs E, Green H. Changes in keratin gene expression during terminal differentiation of the keratinocyte. Cell. 1980;19:1033–1042. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90094-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bloor BK, Seddon SV, Morgan PR. Gene expression of differentiation-specific keratins (K4, K13, K1 and K10) in oral non-dysplastic keratoses and lichen planus. J Oral Pathol Med. 2000;29:376–384. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2000.290803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.dos Santos JN, de Sousa SO, Nunes FD, Sotto MN, de Araujo VC. Altered cytokeratin expression in actinic cheilitis. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:237–241. doi: 10.1046/j.0303-6987.2002.028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bloor BK, Tidman N, Leigh IM, Odell E, Dogan B, Wollina U, Ghali L, Waseem A. Expression of keratin K2e in cutaneous and oral lesions: association with keratinocyte activation, proliferation, and keratinization. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:963–975. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63891-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pislariu CI, JDM, Wen J, Cosson V, Muni RR, Wang M, VAB, Andriankaja A, Cheng X, Jerez IT, Mondy S, Zhang S, Taylor ME, Tadege M, Ratet P, Mysore KS, Chen R, Udvardi MK. A Medicago truncatula Tobacco Retrotransposon Insertion Mutant Collection with Defects in Nodule Development and Symbiotic Nitrogen Fixation. Plant Physiol. 2012;159:1686–1699. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.197061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pagano M, Pepperkok R, Verde F, Ansorge W, Draetta G. Cyclin A is required at two points in the human cell cycle. Embo J. 1992;11:961–971. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05135.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Celis JE, Celis A. Cell cycle-dependent variations in the distribution of the nuclear protein cyclin proliferating cell nuclear antigen in cultured cells: subdivision of S phase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:3262–3266. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.10.3262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zuber M. Characterization of a cell cycle-dependent nuclear autoantigen. Mol Biol Rep. 1996;23:197–203. doi: 10.1007/BF00351169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]