Abstract

Unresectable locally advanced pancreatic cancer with or without metastatic disease is associated with a very poor prognosis. Current standard therapy is limited to chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy. Few regimens have been shown to have a substantial survival advantage and novel treatment strategies are urgently needed. Thermal and laser based ablative techniques are widely used in many solid organ malignancies. Initial studies in the pancreas were associated with significant morbidity and mortality, which limited widespread adoption. Modifications to the various applications, in particular combining the techniques with high quality imaging such as computed tomography and intraoperative or endoscopic ultrasound has enabled real time treatment monitoring and significant improvements in safety. We conducted a systematic review of the literature up to October 2013. Initial studies suggest that ablative therapies may confer an additional survival benefit over best supportive care but randomised studies are required to validate these findings.

Keywords: Pancreatic cancer, Radiofrequency ablation, Photodynamic therapy, Cryoablation, Microwave ablation, High frequency focused ultrasound, Irreversible electroporation

Core tip: Unresectable locally advanced pancreatic cancer with or without metastatic disease is associated with a very poor prognosis. Current standard therapy is limited to chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy. Few regimens have been shown to have a substantial survival advantage and novel treatment strategies are urgently needed. Initial studies of ablation in the pancreas were associated with significant morbidity and mortality, which limited widespread adoption. Modifications to the various applications, in particular combining the techniques with high quality imaging such as computed tomography and intraoperative or endoscopic ultrasound has enabled real time treatment monitoring and significant improvements in safety.

BACKGROUND

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is the tenth most common cancer in the UK but the fifth commonest cause of cancer death. At diagnosis more than 80% of patients have locally advanced or metastatic disease and are unsuitable for curative surgical resection. Prognosis in pancreatic cancer is dismal; median survival for locally advanced disease is just 6-10 mo, however in patients with metastatic disease this falls to 3-6 mo. Overall 5 year survival is less than 4%[1].

Standard options available for treating patients with inoperable PDAC are limited to chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or a combination of the two. Gemcitabine is the most commonly used chemotherapy agent in pancreatic cancer, however recent studies have shown that in combination with other chemotherapy agent’s further improvements in overall survival can be gained. A recent randomised Phase III study (GemCap) reported a median survival in the combination gemcitabine + capecitabine group of 7.1 mo compared with 6.2 mo in those who received gemcitabine alone. The 1-year overall survival (OS) rates were 24.3% for combination therapy and 22% for gemcitabine alone (HR = 0.86, 95%CI: 0.72-1.02, P = 0.077)[2]. A further large European study compared gemcitabine to FOLFIRINOX (fluorouracil, leucovorin, irinotecan and oxaliplatin) and demonstrated a significant survival advantage in the FOLFIRINOX group compared with gemcitabine alone (median 11.1 mo vs 6.8 mo)[3]. The phase III MPACT study found that weekly intravenous nab-paclitaxel with gemcitabine resulted in a significantly higher overall survival compared to gemcitabine monotherapy (8.5 mo vs 6.7 mo, HR = 0.72, P < 0.0001)[4].

Given that so few patients with PDAC are suitable for curative surgery and most have only a limited response to chemotherapy; tumour debulking or interstitial ablation has been investigated as a potential additional therapy. A recent systematic review compared R2 resections to palliative bypass alone in the management of advanced PDAC. A small non-significant survival advantage was observed in the R2 resection group; 8.2 mo compared to 6.7 mo in the palliative bypass group. However patients undergoing R2 resections had a significantly higher morbidity (RR = 1.75, 95%CI: 1.35-2.26, P < 0.0001), mortality (RR = 2.98, 95%CI: 1.31-6.75, P = 0.009) and longer hospital stay (mean difference, 5 d, 95%CI: 1-9 d, P = 0.02), hence R2 resections are not recommended as part of the standard management of PDAC[5]. However minimally invasive ablative therapies delivered percutaneously or endoscopically have become part of standard therapy in many other solid organ tumours, particularly in patients with inoperable disease or who are unfit for surgical resection[6]. Early studies of local ablation in the pancreas were associated with high morbidity and mortality[7]. However improvements in delivery and in particular combining the technology with high quality real-time imaging, has reduced associated complications. The safety and efficacy of each ablative therapy in non-operable PDAC will be evaluated in this review.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

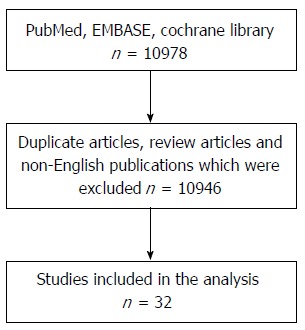

The primary aim of this review was to assess safety and efficacy of each ablation therapy in the treatment of locally advanced or metastatic PDAC. Secondary endpoints included improvements in overall survival, changes in symptoms, tumour markers or performance status where available. A systematic literature search was performed using the PubMed, EMBASE databases and the Cochrane Library for studies published in the English language up to 1st October 2013. MeSH terms were decided by a consensus of the authors and were (radiofrequency ablation, catheter ablation, photodynamic therapy, PDT, cryoablation, cryosurgery, laser, high intensity focused ultrasound ablation, microwave, electroporation) and (pancreas OR pancreatic), and were restricted to the title, abstract and keywords. Only articles, which described ablation in unresectable PDAC, were included. Articles that described the use of ablative therapies in premalignant pancreatic disease were excluded but outcomes are summarised in Table 1. Similarly studies that included non-ablative therapies were also excluded but have been summarised in Table 2. Any study with fewer than four patients and those reporting on tumours that did not originate in the pancreas were excluded. In cryoablation and high frequency focused ultrasound of the pancreas, many of the largest case-series are published in non-English language medical journals. Although articles not published in the English language were excluded from this systematic review, if an English language abstract was available the results were included in the summary tables. All references were screened for potentially relevant studies not identified in the initial literature search. The following variables were extracted for each report when available: number of patients, disease extent, device used and settings, distance of probe from surrounding structures, duration of therapy and number of ablations applied, additional safety methods used. Thirty-two papers were included (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Use of ablative therapies to treat cystic and solid premalignant lesions of the pancreas

| Author | Premalignant lesion | n | Treatment | Median area of ablation, mm (range) | Outcome | Complications |

| Gan et al[46] | Cystic tumours of the pancreas | 25 | EUS guided ethanol lavage | 19.4 (6-30) | Complete resolution 35% | None |

| Oh et al[73] | Cystic tumours of the pancreas | 14 | EUS guided ethanol lavage + paclitaxel | 25.5 (17-52) | Complete resolution in 79% | Acute pancreatitis (n = 1) Hyperamylasaemia (n = 6) Abdominal pain (n = 1) |

| Oh et al[74] | Cystic tumours of the pancreas | 10 | EUS guided ethanol lavage + paclitaxel | 29.5 (20-68) | Complete resolution in 60% | Mild pancreatitis (n = 1) |

| DeWitt et al[75] | Cystic tumours of the pancreas | 42 | Randomised double blind study: Saline vs ethanol | 22.4 (10-58) | Complete resolution in 33% | Abdominal pain at 7 d (n = 5) Pancreatitis (n = 1) Acystic bleeding (n = 1) |

| Oh et al[47] | Cystic tumours of the pancreas | 52 | EUS guided ethanol lavage + paclitaxel | 31.8 (17-68) | Complete resolution in 62% | Fever (1/52) Mild abdominal discomfort (1/52) Mild pancreatitis (1/52) Splenic vein obliteration (1/52) |

| Levy et al[76] | PNET | 8 | EUS guided ethanol lavage (5 patients) and intra-operative ultrasound guided (IOUS) ethanol lavage (3 patients) | 16.6 (8-21) | Hypoglycemia symptoms disappeared 5/8 and significantly improved 3/8 | EUS guided: No complications. IOUS-guided ethanol injection: Minor peritumoral bleeding (1/3), pseudocyst (1/3), pancreatitis (1/3) |

| Pai et al[21] | Cystic tumours of the pancreas + neuroendocrine tumours | 8 | EUS guided RFA | Mean size pre RFA, 38.8 mm vs mean size post RFA, 20 mm | Complete ablation in 25% (2/8) | 2/8 patients had mild abdominal pain that resolved in 3 d |

RFA: Radiofrequency ablation; EUS: Endoscopic ultrasound; PNET: Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumour.

Table 2.

Endoscopic ultrasound administered non-ablative anti-tumour therapies for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

| Author | Therapy | Patients | n | Outcome and survival | Complications |

| Chang et al[77] | Cytoimplant (mixed lymphocyte culture) | Unresectable PDAC | 8 | Median survival: 13.2 mo. 2 partial responders and 1 minor response | 7/8 developed low-grade fever 3/8 required biliary stent placement |

| Hecht et al[78] | ONYX-015 (55-kDa gene-deleted adenovirus) + IV gemcitabine | Unresectable PDAC | 21 | No patient showed tumour regression at day 35. After commencement of gemcitabine, 2/15 had a partial response | Sepsis: 2/15 Duodenal perforation: 2/15 |

| Hecht et al[79] Chang et al[80,81] | TNFerade (replication-deficient adenovector containing human tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α gene) | Locally advanced PDAC | 50 | Response: One complete response, 3 partial responses. Seven patients eventually went to surgery, 6 had clear margins and 3 survived > 24 mo | Dose-limiting toxicities of pancreatitis and cholangitis were observed in 3/50 |

| Herman et al[82] | Phase III study of standard care plus TNFerade (SOC + TNFerade) vs standard care alone (SOC) | Locally advanced PDAC | 304 (187 SOC + TNFerade) | Median survival: 10.0 mo for patients in both the SOC + TNFerade and SOC arms [hazard ratio (HR), 0.90, 95%CI: 0.66-1.22, P = 0.26] | No major complications. Patients in the SOC + TNFerade arm experienced more grade 1 to 2 fever than those in the SOC alone arm (P < 0.001) |

| Sun et al[83] | EUS-guided implantation of radioactive seeds (iodine-125) | Unresectable PDAC | 15 | Tumour response: "partial" in 27% and "minimal" in 20%. Pain relief: 30% | Local complications (pancreatitis and pseudocyst formation) 3/15. Grade III hematologic toxicity in 3/15 |

| Jin et al[84] | EUS-guided implantation of radioactive seeds (iodine-125) | Unresectable PDAC | 22 | Tumour response: “partial” in 3/22 (13.6%) | No complications |

PDAC: Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; EUS: Endoscopic ultrasound.

Figure 1.

Systematic review schema.

THERMAL ABLATIVE TECHNIQUES

Radiofrequency ablation

Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) causes tissue destruction through the application of a high frequency alternating current that generates high local temperatures leading to a coagulative necrosis. The technique has been widely used in many solid organ malignancies and is now part of standard therapy in several tumours including hepatocellular carcinoma[6]. The first application of RFA in the normal porcine pancreas was described in 1999. Although this application was performed under EUS guidance[8] it has nearly always been delivered intraoperatively (rarely percutaneously) in combination with palliative bypass surgery[9]. Although RFA was deemed to be feasible and safe in animal studies[8], early clinical applications in the pancreas were associated with unacceptably high rates of morbidity (0%-40%) and mortality (0%-25%) (Table 3)[7,10-14]. Most RFA of pancreatic tumours has been performed using the Cool-tip™ RF Ablation system (Radionics). Many of the complications arose as a result of inadvertent damage to structures adjacent to the zone of ablation such as the normal pancreas, duodenum, biliary tree or peri-pancreatic vasculature. These early studies applied high temperatures (> 90 °C) and multiple rounds of ablation to treat large tumours in the head of the pancreas in one session[13]. An ex-vivo study of the thermal kinetic characteristics of RFA found that the optimal settings for RFA in the pancreas to prevent injury to the adjacent viscera was 90 °C applied for 5 min[15]. Subsequent clinical studies that reduced the RFA temperature from 105 °C to 90 °C, reported only minimal RFA-related complications[7]. Active cooling of the major vessels and duodenum with saline during intraoperative RFA and observing at least a 0.5 cm area between the zone of ablation and major structures, reduced complications[10,16,17]. Since most of the mortality resulted from uncontrollable gastrointestinal haemorrhage from ablated tumours in the head of the pancreas, some authors have recommended this probe should only be employed in body or tail tumours[10,16].

Table 3.

Studies of radiofrequency ablation in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

| Study | Patients | n | Route of administration | Device | RFA temp (°C) | RFA duration (min) | Outcome | Complications |

| Matsui et al[12] | Unresectable PDAC | 20 LA:9 M:11 | At laparotomy 4 RFA probes were inserted into the tumour 2 cm apart | A 13.56-MHz RFA pulse was produced by the heating apparatus | 50 | 15 | Survival: 3 mo | Mortality: 10% (septic shock and gastrointestinal bleeding) |

| Hadjicostas et al[14] | Locally advanced and unresectable PDAC | 4 | Intraoperative (followed by palliative bypass surgery) | Cool-tip™ RFAblation system | NR | 2-8 | All patients were alive one year post-RFA | No complications encountered |

| Wu et al[10] | Unresectable PDAC | 16 LA:11 M:5 | Intraoperative | Cool-tip™ RFAblation system | 30-90 | 12 at 30 °C then 1 at 90 °C | Pain relief: back pain improved (6/12) | Mortality: 25% (4/16) Pancreatic fistula: 18.8% (3/16) |

| Spiliotis et al[11] | Stage III and IV PDAC receiving palliative therapy | 12 LA:8 M:4 | Intraoperative (followed by palliative bypass surgery) | Cool-tip™ RFAblation system | 90 | 5-7 | Mean survival: 33 mo | Morbidity: 16% (biliary leak) Mortality: 0% |

| Girelli et al[7] | Unresectable locally advanced PDAC | 50 | Intraoperative (followed by palliative bypass surgery) | Cool-tip™ RFAblation system | 105 (25 pts) 90 (25 pts) | Not reported | Not reported | Morbidity 40% in the first 25 patients. Probe temperature decreased from 105°C to 90 °C Morbidity 8% in second cohort of 25 patients. 30-d mortality: 2% |

| Girelli et al[50] | Unresectable locally advanced PDAC | 100 | Intraoperative (followed by palliative bypass surgery) | Cool-tip™ RFAblation system | 90 | 5-10 | Median overall survival: 20 mo | Morbidity: 15%. Mortality: 3% |

| Giardino et al[51] | Unresectable PDAC. 47 RFA alone. 60 had RFA + radiochemotherapy (RCT) and/or intra-arterial systemic chemotherapy (IASC) | 107 | Intraoperative (followed by palliative bypass surgery) | Cool-tip™ RFAblation system | 90 | 5-10 | Median overall survival: 14.7 mo in RFA alone but 25.6 mo in those receiving RFA + RCT and/or IADC (P = 0.004) | Mortality: 1.8% (liver failure and duodenal perforation) Morbidity: 28% |

| Arcidiacono et al[19] | Locally advanced PDAC | 22 | EUS-guided | Cryotherm probe; bipolar RFA + cryogenic cooling | NR | 2-15 | Feasible in 16/22 (72.8%) | Pain (3/22) |

| Steel et al[41] | Unresectable malignant bile duct obstruction (16/22 due to PDAC) | 22 | RFA + SEMS placement at ERCP | Habib EndoHPB wire guided catheter | NR | Sequential 2 min treatments - median 2 (range 1-4) | Median survival: 6 mo Successful biliary decompression (21/22) | Minor bleeding (1/22) Asymptomatic biochemical pancreatitis (1/22), percutaneous gallbladder drainage (2/22). At 90-d, 2/22 had died, one with a patent SEMS |

| Figueroa-Barojas et al[42] | Unresectable malignant bile duct obstruction (7/20 due to PDAC) | 20 | RFA + SEMS placement at ERCP | Habib EndoHPB wire guided catheter | NR | Sequential 2 min treatments | SEMS occlusion at 90 d (3/22) Bile duct diameter increased by 3.5mm post RFA (P = 0.0001) | Abdominal pain (5/20), mild post-ERCP pancreatitis and cholecystitis (1/20) |

| Pai et al[20] | Locally advanced PDAC | 7 | EUS-guided | Habib EUS-RFA catheter | NR | Sequential 90s treatments - median 3 (range 2-4) | 2/7 tumours decreased in size | Mild pancreatitis: (1/7) |

PDAC: Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; LA: Locally advanced PDAC; M: Metastatic PDAC; SEMS: Self-expanding metal stent; RFA: Radiofrequency ablation; EUS: Endoscopic ultrasound; ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

All studies have demonstrated that RFA leads to tumour necrosis and a decrease of tumour volume[9,12,17,18]. Some studies have also observed an improvement in tumour related symptoms, in particular a reduction of back pain and analgesia requirements. Tumour markers (carbohydrate antigen 19-9) also decrease following effective ablation[16]. Although all patients treated with RFA ultimately developed disease progression[9,11,12,17,18], when compared to patients with advanced disease who received standard therapy in a non-randomised cohort study, patients who received combination therapy had prolonged survival (33 mo vs 13 mo, P = 0.0048)[11]. However, this was a single centre study that only included 25 patients (12 receiving RFA). An earlier non-randomised study did not demonstrate the same survival advantage[12]. Spiliotis et al[11] also evaluated overall survival following RFA according to tumour stage. Patients with stage III disease had a significant improvement in survival following RFA compared to patients with the same stage of disease receiving best supportive care (P = 0.0032). In contrast, no difference in overall survival was shown in patients with metastatic PDAC, following RFA treatment (P = 0.1095). Larger studies, in combination with systemic chemotherapy, would be needed to evaluate any potential role of RFA in patients with metastatic disease.

Recently two new RFA probes have been developed that can be placed down the working channel of an endoscope, enabling RFA to be administered under EUS guidance. Twenty-two patients with locally advanced PDAC were treated with the cryotherm probe (CTP) (ERBE Elektromedizin GmbH, Tübingen, Germany) that incorporates radiofrequency ablation with cryogenic cooling. The probe was sited successfully in 16 patients (72.8%); stiffness of the gastrointestinal wall and tumour prevented placement in the others. Following the procedure three patients reported mild abdominal pain and one experienced minor gastrointestinal bleeding, not requiring transfusion[19]. In a further study, 7 patients with unresectable PDAC received EUS guided RFA using the monopolar radiofrequency (RF) catheter (1.2 mm Habib EUS-RFA catheter, Emcision Ltd, London). The tumour was shown to decrease in size in all cases and only one patient developed mild pancreatitis[20]. Long-term follow up is not available on the efficacy of these new catheters. Early clinical studies have also used the Habib EUS RFA catheter to treat cystic tumours of the pancreas (Table 1)[21].

Microwave ablation

Microwave (MW) current is produced by a generator connected via a coaxial cable to 14-gauge straight MW antennas with a 3.7 cm or 2 cm radiating section. One or two antennae are then inserted into the tumour for 10 min. The largest case series of microwave ablation in locally advanced PDAC includes 15 patients. Although MW ablation can be performed percutaneously or intraoperatively[22], in this series it was performed intraoperatively at the time of palliative bypass surgery. All tumours were located in the head or body of the pancreas and had an average size of 6 cm (range 4-8 cm); none had distant metastasis on imaging. Partial necrosis was achieved in all patients and there was no major procedure-related morbidity or mortality. However minor complications were seen in 40% (mild pancreatitis, asymptomatic hyperamylasia, pancreatic ascites, and minor bleeding). The longest survival of an individual patient in this series was 22 mo[23].

Cryoablation

The successful use of cryoablation in the pancreas was first reported in primate experiments in the 1970s[24]. However its potential application as a therapy in pancreatic cancer was not described for a further 20 years[25]. Cryoablation is most commonly performed intra-operatively under ultrasound guidance. Small lesions (< 3 cm) can be reliably frozen with a single, centrally placed probe but larger tumours require the placement of multiple probes or sequential treatments. Most studies have used the argon-gas-based cryosurgical unit (Endocare, Inc., CA, United States) and employ a double “freeze/thaw” cycle. The tumour is cooled to -160 °C and the resulting iceball monitored with ultrasound to ensure the frozen region encompasses the entire mass and does not compromise local structures. The tissue is then allowed to slowly thaw to 0 °C and a second cycle of freezing is performed after any necessary repositioning of the cryoprobes. Like in many of the RFA studies, the authors advocated a 0.5 cm margin of safety from major structures and that ideally the procedure should be performed at the same time as palliative bypass surgery or endoscopic biliary and duodenal stenting. Ablation of liver metastases can also be performed simultaneously[26].

The largest experience of intraoperative and percutaneous cryoablation in pancreatic cancer has been reported from Asia. To date more than 200 patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer have undergone cryoablation alone or in combination with other therapies (Table 4). Effective control of pain, normalisation of CA 19-9, improvement in performance status and prolonged survival have all been reported following cryoablation. Rates of significant complications appear to be lower than in other methods of ablation. Although some patients did encounter delayed gastric emptying following the treatment, this commonly settled with conservative management within a few days. Studies to date are summarised in Table 5. The process has also been shown to initiate antiangiogenesis and a systemic immunological response, which may promote additional anti-tumour effects[27,28]. However evaluation through larger studies will be necessary to fully determine this effect.

Table 4.

Studies of cryoablation in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

| Study | n | Patients | Study | Outcome | Complications |

| Patiutko et al[25] (non-English article) | 30 | Locally advanced PDAC | Combination of cryosurgery and radiation | Pain relief and improvement in performance status: 30/30 | Not reported |

| Kovach et al[52] | 9 | Unresectable PDAC | Phase I study of intraoperative cryoablation under US guidance. Four had concurrent gastrojejunostomy | 7/9 discharged with non-intravenous analgesia and 1/9 discharged with no analgesia | No complications reported |

| Li et al[53] (non-English article) | 44 | Unresectable PDAC | Intraoperative cryoablation under US guidance | Median overall survival: 14 mo | 40.9% (18/44) had delayed gastric empting. 6.8% (3/44) had a bile and pancreatic leak |

| Wu et al[54] (non-English article) | 15 | Unresectable PDAC | Intraoperative cryoablation under US guidance | Median overall survival: 13.4 mo | 1/15 patients developed a bile leak |

| Yi et al[55] (non-English article) | 8 | Unresectable PDAC | Intraoperative cryoablation under US guidance | Not reported | 25% (2/8) developed delayed gastric emptying |

| Xu et al[26] | 38 | Locally advanced PDAC, 8 had liver metastases | Intraoperative or percutaneous cryoablation under US or CT guidance + (125) iodine seed implantation | Median overall survival: 12 mo. 19/38 (50.0%) survived more than 12 mo | Acute pancreatitis: 5/38 (one has severe pancreatitis) |

| Xu et al[56] | 49 | Locally advanced PDAC, 12 had liver metastases | Intraoperative or percutaneous cryoablation under US or CT guidance and (125) iodine seed implantation. Some patients also received regional celiac artery chemotherapy | Median survival: 16.2 mo. 26 patients (53.1%) survived more than 12 mo | Acute pancreatitis: 6/49 (one had severe pancreatitis) |

| Li et al[57] | 68 | Unresectable PDAC requiring palliative bypass | Retrospective case-series of intraoperative cryoablation under US guidance, followed by palliative bypass | Median overall survival: 30.4 mo (range 6-49 mo) | Postoperative morbidity: 42.9%. Delayed gastric emptying occurred in 35.7% |

| Xu et al[58] | 59 | Unresectable PDAC | Intraoperative or percutaneous cryotherapy | Median survival: 8.4 mo. Overall survival at 12 mo: 34.5% | Mild abdominal pain: 45/59 (76.3%) Major complications (bleeding, pancreatic leak): 3/59 (5%) 1/59 developed a tract metastasis |

| Niu et al[29] | 36 (CT) 31 (CIT) | Metastatic PDAC | Intraoperative cryotherapy (CT) or cryoimmunotherapy (CIT) under US guidance | Median overall survival in CIT: 13 mo CT: 7 mo | Not reported |

PDAC: Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.

Table 5.

Studies of photodynamic therapy in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

| Study | n | Study | Photosensitiser | Number of fibres | Number of ablations | Outcome and survival | Complications |

| Bown et al[30] | 16 | CT guided percutaneous PDT to locally advanced but inoperable PDAC without metastatic disease | mTH-PC | Single | 1 | Tumour necrosis: 16/16. Median survival: 9.5 mo. 44% (7/16) survived > 1 year | Significant gastrointestinal bleeding: 2/16 (controlled without surgery) |

| Huggett et al[31,32] | 13 + 2 | CT guided percutaneous PDT to locally advanced but inoperable PDAC without metastatic disease | Verteporfrin | Single (13) Multiple (2) | 1 | Technically feasible: 15/15. Dose dependent necrosis occurred | Single fibre: No complications. Multiple fibres: CT evidence of inflammatory change anterior to the pancreas, no clinical sequelae |

PDAC: Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; CT: Computed tomography.

Early clinical studies have also combined the administration of cryotherapy with immunotherapy. In a study of 106 patients with unresectable PDAC, 31 received cryoimmunotherapy, 36 cryotherapy, 17 immunotherapy and 22 chemotherapy. Median overall survival was higher in the cryoimmunotherapy (13 mo) and cryotherapy groups (7 mo) than in the chemotherapy group (3.5 mo; both P < 0.001) and was higher in the cryoimmunotherapy group than in the cryotherapy (P < 0.05) and immunotherapy groups (5 mo; P < 0.001)[29].

LASER BASED ABLATIVE THERAPY

Photodynamic therapy

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) results in tumour ablation by exposure to light following an intravenous injection of a photosensitiser [e.g., meso-tetra(hydroxyphenyl)chlorin (mTHPC), porfimer sodium or verteporfin] which is taken up by cells. It leads to a predictable zone of ablation within the tumour. To date, light has been delivered via small optic fibers which have nearly always been positioned percutaneously under image guidance (e.g., CT)[30-32]. However these fibers can pass through a 19G needle, so administration under endoscopic ultrasound guidance is feasible.

The first Phase I trial of PDT in locally advanced PDAC was conducted in 2002. Substantial tumour necrosis was achieved in all 16 patients included in the study. Median survival after PDT was 9.5 mo (range 4-30 mo). 44% (7/16) were alive one year after PDT. Two of the patients who had a pancreatic tumor which involved the gastroduodenal artery developed significant gastrointestinal bleeding following the procedure. However both were managed endoscopically with transfusion, without the need for surgery[30].

A significant drawback of the early PDT treatments was that patients had to spend several days in subdued lighting following the treatment to prevent complications from skin necrosis. However, newer photosensitisers with a shorter drug-light interval and faster drug elimination time have been developed (e.g., verteporfrin) and have been shown in preclinical and early clinical studies to have a similar efficacy and safety profile to mTHPC[33]. A Phase I study by our group evaluated verteporfin-mediated PDT in 15 patients with unresectable locally advanced pancreatic cancer (Vertpac-01) (Table 5)[31,32]. The study was designed in 2 parts: the first 13 patients were treated with a single-fibre, with the following 2 patients being treated with light from multiple fibers. A predictable zone of necrosis surrounding the fibers was achieved. No instances of photosensitivity were reported and only one patient developed cholangitis. Patient went on to receive palliative gemcitabine chemotherapy 28 d after ablation.

YAG Laser

The neodymium-doped yttrium aluminium garnet (Nd:YAG) laser has been used to ablate pancreatic tumours in animal models[34]. A well demarcated area of necrosis and no complications were achieved, suggesting the potential for this therapy, but to date there have been no clinical studies.

NON-THERMAL, NON-LASER METHODS OF ABLATION

Many of the studies of thermal and light ablation techniques in locally advanced and metastatic PDAC have suggested that cytoreduction may improve survival. However in the initial clinical studies some of the techniques were associated with unacceptably high rates of complications. This has led to a search for non-thermal alternative ablative therapies for use in PDAC.

High-intensity focused ultrasound

High intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) therapy is a non-invasive method of ablation. Ultrasound energy from an extracorporeal source is focused on the pancreatic tumour to induce thermal denaturation of tissue without affecting surrounding organs[35]. Multiple non-randomised studies and case series, largely from Asia, have reported preliminary clinical experiences of using HIFU in PDAC. They have demonstrated that the technique is able to achieve tumour necrosis with relatively few side effects (Table 6). Recently a HIFU transducer has been designed which can be attached to an EUS scope to deliver HIFU locally to pancreatic tumours, thus preventing occasional burns to the skin. Initial animal studies have demonstrated that it can successfully abate the normal pancreas and liver[36].

Table 6.

Studies of high intensity focused ultrasound in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

| Study | n | Study | Outcome and survival | Complications |

| Wang et al[59] (non-English article) | 15 | HIFU monotherapy in late stage PDAC | Pain relief: 13/13 (100%) | Mild abdominal pain (2/15) |

| Xie et al[60] (non-English article) | 41 | HIFU alone vs HIFU + gemcitabine in locally advanced PDAC | Pain relief: HIFU (66.7%), | None |

| HIFU + gemcitabine (76.6%) | ||||

| Xu et al[61] (non-English article) | 37 | HIFU monotherapy in advanced PDAC | Pain relief: 24/30 (80%) | None |

| Yuan et al[62] (non-English article) | 40 | HIFU monotherapy | Pain relief: 32/40 (80%) | None |

| Wu et al[63] | 8 | HIFU in advanced PDAC | Median survival: 11.25 mo | None |

| Pain relief: 8/8 | ||||

| Xiong et al[64] | 89 | HIFU in unresectable PDAC | Median survival: 26.0 mo (stage II), 11.2 mo (stage III) and 5.4 mo (stage IV) | Superficial skin burns (3.4%), subcutaneous fat sclerosis (6.7%), asymptomatic pseudocyst (1.1%) |

| Zhao et al[65] | 37 | Phase II study of gemcitabine + HIFU in locally advanced PDAC | Overall survival: 12.6 mo (95%CI: 10.2-15.0 mo) Pain relief: 78.6% | 16.2% experienced grade 3 or 4 neutropenia, 5.4% developed grade 3 thrombocytopenia, 8% had nausea vomiting |

| Orsi et al[66] | 6 | HIFU in unresectable PDAC | Pain relief: 6/6 (100%) | Portal vein thrombosis (1/6) |

| Sung et al[67] | 46 | Stage III or IV PDAC | Median survival: 12.4 mo. Overall survival at 12 mo was 30.4% | Minor complications (abdominal pain, fever and nausea): 57.1% (28/29) Major complications (pancreaticoduodenal fistula, gastric ulcer or skin burns): 10.2% (5/49) |

| Wang et al[68] | 40 | Advanced PDAC | Median overall survival: 10 mo (stage III) and 6 mo (stage IV). Pain relief: 35/40 (87.5%) | None |

| Lee et al[69] | 12 | HIFU monotherapy in unresectable PDAC (3/12 received chemotherapy) | Median overall survival for those receiving HIFU alone (9/12 patients): 10.3 mo | Pancreatitis: 1/12 |

| Li et al[70] | 25 | Unresectable PDAC | Median overall survival: 10 mo. 42% survived more than 1 year. Performance status and pain levels improved: 23/25 | 1st degree skin burn: 12% Mortality: 0% |

| Wang et al[71] | 224 | Advanced PDAC | Not reported | Abdominal distension, anorexia and nausea: 10/ 224 (4.5%). Asymptomatic vertebral injury: 2/224 |

| Gao et al[72] | 39 | Locally advanced PDAC | Pain relief: 79.5% Median overall survival: 11 mo. 30.8% survived more than one year | None |

HIFU: High intensity focused ultrasound; PDAC: Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.

Irreversible electroporation

NanoKnife® (Angiodynamics, Inc., NY, United States) or irreversible electroporation (IRE) is an emerging non-thermal ablative technique which uses electrodes, placed in the tumour, to deliver up to 3 kV of direct current. This induces the formation of nanoscale pores within the cell membrane of the targeted tissue, which irreversibly damages the cell’s homeostatic mechanism, causing apoptosis. The United States Food and Drug Administration have recently approved the technique for use in the pancreas.

One of the major advantages of this technique is that it can be used in tumours that are in close proximity to peri-pancreatic vessels without risk of vascular trauma. The largest series of percutaneous IRE in PDAC includes 14 patients who had unresectable tumours and were not candidates for, or were intolerant of standard therapy[37]. The procedure was performed under general anaesthesia with complete muscle paralysis. Two patients subsequently underwent surgery after IRE and both had margin-negative resections; both remain disease-free after 11 and 14 mo, respectively. Complications included spontaneous pneumothorax during anaesthesia (n = 1) and pancreatitis (n = 1); both patients recovered completely. No deaths were related to the procedure but the three patients with metastatic disease subsequently died from disease progression.

COMBINING ABLATIVE THERAPIES WITH BILIARY STENTING

Tumours of the head of the pancreas commonly cause distal biliary obstruction, which is managed in most cases by an endoscopically inserted self-expanding metal stent (SEMS). However due to tumour ingrowth SEMS are associated with a shorter patency time than bypass surgery. Hence there has been a growth in interest in using ablative therapies such as PDT or RFA to prolong stent patency or to unblock a SEMS, which is already in situ. Randomised studies comparing PDT with biliary stenting to stenting alone have had conflicting results. Initial studies reported prolonged stent patency and improved survival after PDT[38,39]. However, a recent UK phase III study closed early as overall survival was longer in those treated with stenting alone[40]. The use of RFA in combination with SEMS placement has been reported in two small studies to date (Table 3). The investigators showed that the median bile duct diameter increased following endobiliary RFA and that 86% (19/22) of the SEMS were patent at 90 d[41,42]. Emerging evidence also suggests that endobiliary RFA may confer some early survival benefit in patients with malignant biliary obstruction independent of stent blockage and chemotherapy[41]. Occasionally centres have used RFA alone to achieve biliary drainage but results of on-going randomised controlled trials are awaited for validation of this technique[43]. Current guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in the United Kingdom recommends that this treatment should only be carried out in specialist centres in the context of clinical trials[44].

ENDOSCOPIC ULTRASOUND GUIDED NON-ABLATIVE LOCAL THERAPIES

Systemic chemotherapy agents are often associated with significant side effects, which can result in patients having to stop therapy or undergo dose reduction. Several groups have therefore explored using local anti-tumour agents in PDAC. The outcomes are summarised in Table 2.

PREMALIGNANT LESIONS OF THE PANCREAS

Some investigators have used similar ablative methods in PDAC to ablate premalignant solid and cystic lesions of the pancreas. Cystic lesions of the pancreas are an increasingly common clinical finding and some possess premalignant potential; longterm surveillance or surgery or pancreatic surgery is therefore recommended in accordance with international guidance[45]. Given the morbidity of surgery and uncertainties of surveillance for essentially benign disease, minimally invasive ablative therapies are increasingly becoming an attractive alternative treatment.

An EUS-guided injection of alcohol has been reported to have reasonable efficacy for achieving complete ablation of pancreatic cystic tumours (35%-62%). However, total cyst ablation was rare in septated cysts and the technique was associated with complications (pain and pancreatitis) in between 4%-20% of cases[46,47]. Occasional case reports have described using EUS guided alcohol injection to successfully ablate hepatic metastases[48] and pancreatic gastrointestinal stromal tumours[49]. Small case series have demonstrated EUS guided RFA can also be used safely for this indication[21]. Further validation will come from larger Phase II studies.

CONCLUSION

Ablative therapies for unresectable pancreatic cancer are an attractive emerging therapy. All studies demonstrated that ablation is feasible and reproducible. Many of the early concerns that surrounded safety have been addressed with device development and modification of technique. Long-term survival data for many of the techniques is absent currently. Ultimately large prospective randomised studies will be required to assess the efficacy of these techniques and define their position in future treatment algorithms for the management of locally advanced pancreatic cancer.

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health Grant PO1CA84203; The work was undertaken at UCLH/UCL, which receives a proportion of funding from the Department of Health’s National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centres funding scheme; A CRUK research bursary to Keane MG

P- Reviewers: Clark CJ, Dai ZJ, Sierzega M S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

References

- 1.Cancer Research UK. Pancreatic cancer statistics 2010. Available from: http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/cancer-info/cancerstats/types/pancreas.

- 2.Cunningham D, Chau I, Stocken DD, Valle JW, Smith D, Steward W, Harper PG, Dunn J, Tudur-Smith C, West J, et al. Phase III randomized comparison of gemcitabine versus gemcitabine plus capecitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5513–5518. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, Bouché O, Guimbaud R, Bécouarn Y, Adenis A, Raoul JL, Gourgou-Bourgade S, de la Fouchardière C, et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1817–1825. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.VonHoff DD, Ervin TJ, Arena FP, Chiorean EG, Infante JR, Moore MJ, Seay TE, Tjulandin S, Ma WW, Saleh MN, et al. Randomized phase III study of weekly nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine vs gemcitabine alone in patients with metastatic adenocarcinoma of the pancreas (MPACT) J Clin Oncol. 2013;30 supp 34:abstr LBA148. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gillen S, Schuster T, Friess H, Kleeff J. Palliative resections versus palliative bypass procedures in pancreatic cancer--a systematic review. Am J Surg. 2012;203:496–502. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Llovet JM, Brú C, Bruix J. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: the BCLC staging classification. Semin Liver Dis. 1999;19:329–338. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Girelli R, Frigerio I, Salvia R, Barbi E, Tinazzi Martini P, Bassi C. Feasibility and safety of radiofrequency ablation for locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg. 2010;97:220–225. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldberg SN, Mallery S, Gazelle GS, Brugge WR. EUS-guided radiofrequency ablation in the pancreas: results in a porcine model. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:392–401. doi: 10.1053/ge.1999.v50.98847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Date RS, Siriwardena AK. Radiofrequency ablation of the pancreas. II: Intra-operative ablation of non-resectable pancreatic cancer. A description of technique and initial outcome. JOP. 2005;6:588–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu Y, Tang Z, Fang H, Gao S, Chen J, Wang Y, Yan H. High operative risk of cool-tip radiofrequency ablation for unresectable pancreatic head cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2006;94:392–395. doi: 10.1002/jso.20580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spiliotis JD, Datsis AC, Michalopoulos NV, Kekelos SP, Vaxevanidou A, Rogdakis AG, Christopoulou AN. Radiofrequency ablation combined with palliative surgery may prolong survival of patients with advanced cancer of the pancreas. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2007;392:55–60. doi: 10.1007/s00423-006-0098-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsui Y, Nakagawa A, Kamiyama Y, Yamamoto K, Kubo N, Nakase Y. Selective thermocoagulation of unresectable pancreatic cancers by using radiofrequency capacitive heating. Pancreas. 2000;20:14–20. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200001000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elias D, Baton O, Sideris L, Lasser P, Pocard M. Necrotizing pancreatitis after radiofrequency destruction of pancreatic tumours. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2004;30:85–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2003.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hadjicostas P, Malakounides N, Varianos C, Kitiris E, Lerni F, Symeonides P. Radiofrequency ablation in pancreatic cancer. HPB (Oxford) 2006;8:61–64. doi: 10.1080/13651820500466673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Date RS, McMahon RF, Siriwardena AK. Radiofrequency ablation of the pancreas. I: Definition of optimal thermal kinetic parameters and the effect of simulated portal venous circulation in an ex-vivo porcine model. JOP. 2005;6:581–587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang Z, Wu YL, Fang HQ, Xu J, Mo GQ, Chen XM, Gao SL, Li JT, Liu YB, Wang Y. Treatment of unresectable pancreatic carcinoma by radiofrequency ablation with ‘cool-tip needle’: report of 18 cases. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2008;88:391–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Varshney S, Sewkani A, Sharma S, Kapoor S, Naik S, Sharma A, Patel K. Radiofrequency ablation of unresectable pancreatic carcinoma: feasibility, efficacy and safety. JOP. 2006;7:74–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siriwardena AK. Radiofrequency ablation for locally advanced cancer of the pancreas. JOP. 2006;7:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arcidiacono PG, Carrara S, Reni M, Petrone MC, Cappio S, Balzano G, Boemo C, Cereda S, Nicoletti R, Enderle MD, et al. Feasibility and safety of EUS-guided cryothermal ablation in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:1142–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pai M, Yang J, Zhang X, Jin Z, Wang D, Senturk H, Lakhtakia S, Reddy DN, Kahaleh M, Habib N, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound guided radiofrequency ablation (EUS-RFA) for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Gut. 2013;62(Suppl 1):A153. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pai M, Senturk H, Lakhtakia S, Reddy DN, Cicinnati C, Kabar I, Beckebaum S, Jin Z, Wang D, Yang J, et al. Endoscopic Ultrasound Guided Radiofrequency Ablation (EUS-RFA) for Cystic Neoplasms and Neuroendocrine Tumours of the Pancreas. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77(5S):AB143–AB144. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carrafiello G, Ierardi AM, Fontana F, Petrillo M, Floridi C, Lucchina N, Cuffari S, Dionigi G, Rotondo A, Fugazzola C. Microwave ablation of pancreatic head cancer: safety and efficacy. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013;24:1513–1520. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lygidakis NJ, Sharma SK, Papastratis P, Zivanovic V, Kefalourous H, Koshariya M, Lintzeris I, Porfiris T, Koutsiouroumba D. Microwave ablation in locally advanced pancreatic carcinoma--a new look. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54:1305–1310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Myers RS, Hammond WG, Ketcham AS. Cryosurgery of primate pancreas. Cancer. 1970;25:411–414. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197002)25:2<411::aid-cncr2820250220>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patiutko IuI, Barkanov AI, Kholikov TK, Lagoshnyĭ AT, Li LI, Samoĭlenko VM, Afrikian MN, Savel'eva EV. The combined treatment of locally disseminated pancreatic cancer using cryosurgery. Vopr Onkol. 1991;37:695–700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu KC, Niu LZ, Hu YZ, He WB, He YS, Zuo JS. Cryosurgery with combination of (125)iodine seed implantation for the treatment of locally advanced pancreatic cancer. J Dig Dis. 2008;9:32–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-9573.2007.00322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Korpan NN. Cryosurgery: ultrastructural changes in pancreas tissue after low temperature exposure. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2007;6:59–67. doi: 10.1177/153303460700600202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joosten JJ, Muijen GN, Wobbes T, Ruers TJ. In vivo destruction of tumor tissue by cryoablation can induce inhibition of secondary tumor growth: an experimental study. Cryobiology. 2001;42:49–58. doi: 10.1006/cryo.2001.2302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Niu L, Chen J, He L, Liao M, Yuan Y, Zeng J, Li J, Zuo J, Xu K. Combination treatment with comprehensive cryoablation and immunotherapy in metastatic pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2013;42:1143–1149. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3182965dde. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bown SG, Rogowska AZ, Whitelaw DE, Lees WR, Lovat LB, Ripley P, Jones L, Wyld P, Gillams A, Hatfield AW. Photodynamic therapy for cancer of the pancreas. Gut. 2002;50:549–557. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.4.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huggett MT, Jermyn M, Gillams A, Mosse S, Kent E, Bown SG, Hasan T, Pogue BW, Pereira SP. Photodynamic therapy of locally advanced pancreatic cancer (VERTPAC study): Final clinical results. Progress in Biomedical Optics and Imaging - Proceedings of SPIE. 2013:8568. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huggett MT, Jermyn M, Gillams A, Mosse S, Kent E, Bown SG, Hasan T, Pogue BW, Pereira SP. Photodynamic therapy for locally advanced pancreatic cancer (VERTPAC study): final clinical results. Pancreatology. 2013;13:e2–e3. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ayaru L, Wittmann J, Macrobert AJ, Novelli M, Bown SG, Pereira SP. Photodynamic therapy using verteporfin photosensitization in the pancreas and surrounding tissues in the Syrian golden hamster. Pancreatology. 2007;7:20–27. doi: 10.1159/000101874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Di Matteo F, Martino M, Rea R, Pandolfi M, Rabitti C, Masselli GM, Silvestri S, Pacella CM, Papini E, Panzera F, et al. EUS-guided Nd: YAG laser ablation of normal pancreatic tissue: a pilot study in a pig model. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:358–363. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leslie T, Ritchie R, Illing R, Ter Haar G, Phillips R, Middleton M, Bch B, Wu F, Cranston D. High-intensity focused ultrasound treatment of liver tumours: post-treatment MRI correlates well with intra-operative estimates of treatment volume. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:1363–1370. doi: 10.1259/bjr/56737365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hwang J, Farr N, Morrison K. Development of an EUS-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound endoscope. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73(4S):AB155. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Narayanan G, Hosein PJ, Arora G, Barbery KJ, Froud T, Livingstone AS, Franceschi D, Rocha Lima CM, Yrizarry J. Percutaneous irreversible electroporation for downstaging and control of unresectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2012;23:1613–1621. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2012.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zoepf T, Jakobs R, Arnold JC, Apel D, Riemann JF. Palliation of nonresectable bile duct cancer: improved survival after photodynamic therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2426–2430. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gerhardt T, Rings D, Höblinger A, Heller J, Sauerbruch T, Schepke M. Combination of bilateral metal stenting and trans-stent photodynamic therapy for palliative treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Z Gastroenterol. 2010;48:28–32. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1109983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pereira SP, Hughes SK, Roughton M, O’Donoghue P, Wasan HS, Valle J, Bridgewater J. Photostent-02: porfimer sodium photodynamic therapy plus stenting alone in patients (pts) with advanced or metastatic cholangiocarcinomas and other biliary tract tumours (BTC): a multicentre, randomised phase III trial [abstract]; 2010 Oct 8-12; London. Milan, Italy: ESMO; 2010. p. Abstract 802O. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steel AW, Postgate AJ, Khorsandi S, Nicholls J, Jiao L, Vlavianos P, Habib N, Westaby D. Endoscopically applied radiofrequency ablation appears to be safe in the treatment of malignant biliary obstruction. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:149–153. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Figueroa-Barojas P, Bakhru MR, Habib NA, Ellen K, Millman J, Jamal-Kabani A, Gaidhane M, Kahaleh M. Safety and efficacy of radiofrequency ablation in the management of unresectable bile duct and pancreatic cancer: a novel palliation technique. J Oncol. 2013;2013:910897. doi: 10.1155/2013/910897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shariff MI, Khan SA, Westaby D. The palliation of cholangiocarcinoma. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2013;7:168–174. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0b013e32835f1e2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Using radiofrequency energy to treat malignant bile or pancreatic duct obstructions caused by cholangiocarcinoma or pancreatic adenocarcinoma 2013. Available from: http://guidance.nice.org.uk/IPG464/DraftGuidance.

- 45.Tanaka M, Fernández-del Castillo C, Adsay V, Chari S, Falconi M, Jang JY, Kimura W, Levy P, Pitman MB, Schmidt CM, et al. International consensus guidelines 2012 for the management of IPMN and MCN of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2012;12:183–197. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gan SI, Thompson CC, Lauwers GY, Bounds BC, Brugge WR. Ethanol lavage of pancreatic cystic lesions: initial pilot study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:746–752. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)00320-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oh HC, Seo DW, Song TJ, Moon SH, Park do H, Soo Lee S, Lee SK, Kim MH, Kim J. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided ethanol lavage with paclitaxel injection treats patients with pancreatic cysts. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:172–179. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barclay RL, Perez-Miranda M, Giovannini M. EUS-guided treatment of a solid hepatic metastasis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:266–270. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.120784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Günter E, Lingenfelser T, Eitelbach F, Müller H, Ell C. EUS-guided ethanol injection for treatment of a GI stromal tumor. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:113–115. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Girelli R, Giardino A, Frigerio I, Salvia R, Partelli S, Bassi C. Survival after radiofrequency of stage III pancreatic carcinoma: a wind of change. HPB (Oxford) 2011;13(Suppl 2):15. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Giardino A, Girelli R, Frigerio I, Regi P, Cantore M, Alessandra A, Lusenti A, Salvia R, Bassi C, Pederzoli P. Triple approach strategy for patients with locally advanced pancreatic carcinoma. HPB (Oxford) 2013;15:623–627. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kovach SJ, Hendrickson RJ, Cappadona CR, Schmidt CM, Groen K, Koniaris LG, Sitzmann JV. Cryoablation of unresectable pancreatic cancer. Surgery. 2002;131:463–464. doi: 10.1067/msy.2002.121231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li B, Li JD, Chen XL, Zeng Y, Wen TF, Hu WM, Yan LN. Cryosurgery for unresectable pancreatic carcinoma: a report of 44 cases. Zhonghua Gandan Waike Zazhi. 2004;10:523–525. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu Q, Zhang JX, Qian JX, Xu Q, Wang JJ. The application of surgical treatment in combination with targeted cryoablation on advanced carcinoma of head of pancreas: a report of 15 cases. Zhongguo Zhongliu Linchuang. 2005;32:1403–1405. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yi FT, Song HZ, Li J. Intraoperative Ar-He targeted cryoablation for advanced pancreatic carcinoma. Zhonghua Gandan Waike Zazhi. 2006;12:186–187. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xu KC, Niu LZ, Hu YZ, He WB, He YS, Li YF, Zuo JS. A pilot study on combination of cryosurgery and (125)iodine seed implantation for treatment of locally advanced pancreatic cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:1603–1611. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li J, Chen X, Yang H, Wang X, Yuan D, Zeng Y, Wen T, Yan L, Li B. Tumour cryoablation combined with palliative bypass surgery in the treatment of unresectable pancreatic cancer: a retrospective study of 142 patients. Postgrad Med J. 2011;87:89–95. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2010.098350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xu K, Niu L, Yang D. Cryosurgery for pancreatic cancer. Gland Surgery. 2013;2:30–39. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2227-684X.2013.02.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang X, Sun J. High-intensity focused ultrasound in patients with late-stage pancreatic carcinoma. Chin Med J (Engl) 2002;115:1332–1335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xie DR, Chen D, Teng H. A multicenter non-randomized clinical study of high intensity focused ultrasound in treating patients with local advanced pancreatic carcinoma. Zhongguo Zhongliu Linchuang. 2003;30:630–634. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xu YQ, Wang GM, Gu YZ, Zhang HF. The acesodyne effect of high intensity focused ultrasound on the treatment of advanced pancreatic carcinoma. Zhongguo Linchuang Yixue. 2003;10:322–323. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yuan C, Yang L, Yao C. Observation of high intensity focused ultrasound treating 40 cases of pancreatic cancer. Linchuang Gandanbing Zazhi. 2003;19:145–146. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu F, Wang ZB, Zhu H, Chen WZ, Zou JZ, Bai J, Li KQ, Jin CB, Xie FL, Su HB. Feasibility of US-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound treatment in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: initial experience. Radiology. 2005;236:1034–1040. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2362041105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xiong LL, Hwang JH, Huang XB, Yao SS, He CJ, Ge XH, Ge HY, Wang XF. Early clinical experience using high intensity focused ultrasound for palliation of inoperable pancreatic cancer. JOP. 2009;10:123–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhao H, Yang G, Wang D, Yu X, Zhang Y, Zhu J, Ji Y, Zhong B, Zhao W, Yang Z, et al. Concurrent gemcitabine and high-intensity focused ultrasound therapy in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Anticancer Drugs. 2010;21:447–452. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e32833641a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Orsi F, Zhang L, Arnone P, Orgera G, Bonomo G, Vigna PD, Monfardini L, Zhou K, Chen W, Wang Z, et al. High-intensity focused ultrasound ablation: effective and safe therapy for solid tumors in difficult locations. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195:W245–W252. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.3321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sung HY, Jung SE, Cho SH, Zhou K, Han JY, Han ST, Kim JI, Kim JK, Choi JY, Yoon SK, et al. Long-term outcome of high-intensity focused ultrasound in advanced pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2011;40:1080–1086. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31821fde24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang K, Chen Z, Meng Z, Lin J, Zhou Z, Wang P, Chen L, Liu L. Analgesic effect of high intensity focused ultrasound therapy for unresectable pancreatic cancer. Int J Hyperthermia. 2011;27:101–107. doi: 10.3109/02656736.2010.525588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lee JY, Choi BI, Ryu JK, Kim YT, Hwang JH, Kim SH, Han JK. Concurrent chemotherapy and pulsed high-intensity focused ultrasound therapy for the treatment of unresectable pancreatic cancer: initial experiences. Korean J Radiol. 2011;12:176–186. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2011.12.2.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Li PZ, Zhu SH, He W, Zhu LY, Liu SP, Liu Y, Wang GH, Ye F. High-intensity focused ultrasound treatment for patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2012;11:655–660. doi: 10.1016/s1499-3872(12)60241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang K, Zhu H, Meng Z, Chen Z, Lin J, Shen Y, Gao H. Safety evaluation of high-intensity focused ultrasound in patients with pancreatic cancer. Onkologie. 2013;36:88–92. doi: 10.1159/000348530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.High Intensity Focused Ultrasound Treatment for Patients with Local Advanced Pancreatic Cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2013;60:Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.5754/hge13498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Oh HC, Seo DW, Lee TY, Kim JY, Lee SS, Lee SK, Kim MH. New treatment for cystic tumors of the pancreas: EUS-guided ethanol lavage with paclitaxel injection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:636–642. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Oh HC, Seo DW, Kim SC, Yu E, Kim K, Moon SH, Park do H, Lee SS, Lee SK, Kim MH. Septated cystic tumors of the pancreas: is it possible to treat them by endoscopic ultrasonography-guided intervention. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:242–247. doi: 10.1080/00365520802495537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.DeWitt J, McGreevy K, Schmidt CM, Brugge WR. EUS-guided ethanol versus saline solution lavage for pancreatic cysts: a randomized, double-blind study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:710–723. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.03.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Levy MJ, Thompson GB, Topazian MD, Callstrom MR, Grant CS, Vella A. US-guided ethanol ablation of insulinomas: a new treatment option. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:200–206. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chang KJ, Nguyen PT, Thompson JA, Kurosaki TT, Casey LR, Leung EC, Granger GA. Phase I clinical trial of allogeneic mixed lymphocyte culture (cytoimplant) delivered by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle injection in patients with advanced pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer. 2000;88:1325–1335. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000315)88:6<1325::aid-cncr8>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hecht JR, Bedford R, Abbruzzese JL, Lahoti S, Reid TR, Soetikno RM, Kirn DH, Freeman SM. A phase I/II trial of intratumoral endoscopic ultrasound injection of ONYX-015 with intravenous gemcitabine in unresectable pancreatic carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:555–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hecht JR, Farrell JJ, Senzer N, Nemunaitis J, Rosemurgy A, Chung T, Hanna N, Chang KJ, Javle M, Posner M, et al. EUS or percutaneously guided intratumoral TNFerade biologic with 5-fluorouracil and radiotherapy for first-line treatment of locally advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase I/II study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:332–338. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chang KJ, Lee JG, Holcombe RF, Kuo J, Muthusamy R, Wu ML. Endoscopic ultrasound delivery of an antitumor agent to treat a case of pancreatic cancer. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;5:107–111. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chang KJ, Irisawa A. EUS 2008 Working Group document: evaluation of EUS-guided injection therapy for tumors. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:S54–S58. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.10.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Herman JM, Wild AT, Wang H, Tran PT, Chang KJ, Taylor GE, Donehower RC, Pawlik TM, Ziegler MA, Cai H, et al. Randomized phase III multi-institutional study of TNFerade biologic with fluorouracil and radiotherapy for locally advanced pancreatic cancer: final results. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:886–894. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.7516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sun S, Xu H, Xin J, Liu J, Guo Q, Li S. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided interstitial brachytherapy of unresectable pancreatic cancer: results of a pilot trial. Endoscopy. 2006;38:399–403. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-925253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jin Z, Du Y, Li Z, Jiang Y, Chen J, Liu Y. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided interstitial implantation of iodine 125-seeds combined with chemotherapy in the treatment of unresectable pancreatic carcinoma: a prospective pilot study. Endoscopy. 2008;40:314–320. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-995476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]