Abstract

Our community-based participatory research (CBPR) partnership engaged in a multi-step process to refine a culturally congruent intervention that builds on existing community strengths to promote sexual health among immigrant Latino men who have sex with men (MSM). The steps were: (1) increase Latino MSM participation in the existing partnership; (2) establish an Intervention Team; (3) review the existing sexual health literature; (4) explore needs and priorities of Latino MSM; (5) narrow priorities based on what is important and changeable; (6) blend health behavior theory with Latino MSM’s lived experiences; (7) design an intervention conceptual model; (8) develop training modules and (9) resource materials; and (10) pretest and (11) revise the intervention. The developed intervention contains four modules to train Latino MSM to serve as lay health advisors (LHAs) known as “Navegantes”. These modules synthesize locally collected data with other local and national data; blend health behavior theory, the lived experiences, and cultural values of immigrant Latino MSM; and harness the informal social support Latino MSM provide one another. This community-level intervention is designed to meet the expressed sexual health priorities of Latino MSM. It frames disease prevention within sexual health promotion.

Introduction

Latinos have the second highest rate of AIDS diagnoses of all racial and ethnic groups. Nationally, the AIDS case rate among Latinos is three times higher than non-Latino whites and is second to African Americans (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2012). Subpopulation analyses reinforce the severity of the HIV epidemic in men who have sex with men (MSM) of all races and ethnicities. Nearly three-fourths of new infections among males occur from male-to-male sexual contact, including 81% of new infections among whites, 63% among blacks, and 72% among Latinos. Moreover, Latino MSM have twice the rate of HIV infection of white MSM, and most new infections are found in younger Latinos compared to younger whites.

HIV incidence rates in North Carolina (NC) are approximately 40% higher than the national rate, and HIV and STD infection rates for Latinos in NC are three and four times that of non-Latino whites (NC Department of Health and Human Services, 2008, 2010). Behavioral data suggest that Spanish-speaking Latino MSM in NC are disproportionately at risk for HIV compared to English-speaking Latino and non-Latino counterparts (NC State Center for Health Statistics, 2006; Rhodes, Yee, & Hergenrather, 2006). A respondent-driven sample (RDS) to estimate prevalence of sexual risk among a sample of Latino MSM (N=190) in rural NC found that nearly 90% of participants reported multiple male sex partners and more than half had inconsistent condom use during either insertive or receptive anal intercourse with other men during the past three months (Rhodes et al., 2012).

Although a few efficacious HIV prevention interventions exist for MSM (e.g., Mpowerment [Kegeles, Hays, & Coates, 1996] and d-up!: Defend Yourself! [Jones et al., 2008], no published intervention has been found efficacious for Latino MSM (Rausch, Dieffenbach, Cheever, & Fenton, 2011). Thus, our partnership sought to apply a systematic process to refine an existing intervention to reduce HIV and STD risk and promote sexual health among Latino MSM. We based our intervention on the Hombres Manteniendo Bienestar y Relaciones Saludables (HoMBReS; Men Maintaining Wellbeing and Healthy Relationships) and HoMBReS-2 interventions previously developed by our partnership, which increased condom use and HIV testing among predominantly heterosexual Spanish-speaking Latino men (Rhodes, Hergenrather, Bloom, Leichliter, & Montaño, 2009; Rhodes, Hergenrather, et al., 2006; Rhodes, McCoy, et al., 2011).

The goal of the refined intervention known as Hombres Ofreciendo Liderazgo y Ayuda (HOLA; Men Offering Leadership and Help) is to promote sexual health among Spanish-speaking, less-acculturated Latino MSM. The HOLA intervention includes the deliberate selection, careful training, and ongoing support of Latino MSM to serve as lay health advisors (LHAs). We describe the systematic refinement of the intervention through the expansion of the partnership; the integration of formative data, theoretical considerations, and findings from the literature; and the content of the intervention.

Methods

Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR)

CBPR is a an orientation to research that strives to address health needs from positive and ecological perspectives; it is grounded on the strengths and resources of the partnering communities, promotes co-learning, equalizes power among participants, and integrates knowledge acquisition and interventions for the mutual benefit of all partners (Israel et al., 2003; Rhodes, In press). The refinement of the intervention was guided by our ongoing partnership in NC comprised of representatives from public health departments, AIDS service organizations (ASOs), universities, community-based organizations (CBOs), the CDC, and the local Latino community (Rhodes, Hergenrather, et al., 2011; Rhodes, Malow, & Jolly, 2010). Blending the lived experiences of community members, expertise of public health practitioners and other service providers, and sound science has the potential to develop deeper and more informed understandings of health-related phenomena and produce interventions that are more relevant, culturally congruent, and, consequently, more likely to be successful (Cashman et al., 2008; Eng et al., 2005; Minkler, 2002; Rhodes, Duck, Alonzo, Downs, & Aronson, In press; Rhodes, Hergenrather, et al., 2011; Rhodes, Malow, et al., 2010; Wallerstein et al., 2008). Our partnership adheres to several principles, including mutual respect, building upon partner strengths, developing and using relationships and networks to meet objectives, and disseminating findings to community members, policy makers, and research and clinical audiences (Rhodes, Hergenrather, et al., 2011).

Initial Partnership with Latino MSM

We developed the HOLA intervention in response to Latino MSM’s expressed desire for HIV prevention interventions during the initial implementation of the HoMBReS intervention (Rhodes et al., 2009; Rhodes, Hergenrather, et al., 2006). Hearing that the partnership was implementing an intervention for Latino men who were part of local soccer leagues, a group of five Latino gay men who were “out” about their sexual orientation came to a Latino-serving partner CBO to explore programming for Latino gay men. CBO staff felt unprepared to support these men; they had limited experience working with gay men. Thus, they brought this information to the partnership. In turn, representatives from the partnership met with these initial five men and together determined next steps.

The partnership was committed to being responsive to community-initiated requests and aimed to ensure that any research study initiated met community needs and priorities and was developed in authentic partnership with community members. Thus, we used an eleven step process to develop the intervention (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Steps involved in developing the HOLA intervention through CBPR

| Step | Outcome |

|---|---|

| Step 1: Expand partnership | Increased number of Latino MSM participating in the existing CBPR |

| Step 2: Establish Intervention Team | Established an Intervention Team |

| Step 3: Review of existing sexual health literature |

Identified and reviewed the current available literature about risk and sexual health promotion for Latino MSM; initiated creative thinking about the intervention to build on the state of both the science and practice of sexual health promotion among Latino MSM |

| Step 4: Explore health-related needs and priorities |

Conducted iterative individual in-depth interviews and an RDS study with Latino MSM and examined available, locally collected data from other sources |

| Step 5: Refine and narrow intervention priorities |

Narrowed priorities based on 2 key questions:

|

| Step 6: Blend health behavior theory with the lived experiences of community members |

Operationalized theory; selected social cognitive theory and empowerment education as culturally congruent theoretical bases and LHA as a culturally congruent implementation strategy |

| Step 7: Design an intervention conceptual model |

Identified intervention priorities, intervention-specific roles of LHAs (i.e., Navegantes), and outcomes |

| Step 8: Develop intervention training modules |

Prepared intervention goals, objectives, and key messages; and developed intervention activities and materials based on underlying theoretical constructs and Latino MSM’s lived experiences |

| Step 9: Develop materials | Prepared HOLA Training Manual to train Navegantes and all other materials (e.g., condom tips card, APOYO card, DVD scenes ) |

| Step 10: Pretest the intervention | Pretested the intervention |

| Step 11: Revise the intervention | Revised the intervention based on pretest results |

Step 1: Expand partnership

The partnership had regular biweekly meetings that included lay community members, organizational representatives, local business owners, and academic researchers – some of whom are gay men and lesbian women. However, few Latino MSM regularly attended these meetings. Members successfully recruited a core of Latino self-identified gay men, via the networks of the Latino gay men who initially contacted the CBO, and other Latino gay community leaders, to participate in the partnership.

Step 2: Establish an Intervention Team

We established an Intervention Team, a subgroup of the partnership, to direct the Latino MSM-focused effort. The Intervention Team was comprised of Latino MSM (n=4), heterosexual Latino men (n=2), a Latina woman, health department representatives (n=3), AIDS service organization representatives (n=3), Latino business owners (n=2); academic researchers (n=3), and a non-Latina lesbian business owner. This Intervention Team had the full support of the partnership and engaged members in all aspects of the process.

Step 3: Review existing sexual health literature

The Intervention Team reviewed published and unpublished papers, reports, and briefs to identify what was known in terms of predictors of sexual health and sexual health-seeking behavior among Latinos in the US. The Intervention Team also explored sexual health interventions for Latino MSM in the US, examining the demographics of the Latino MSM participating (e.g., ages; English-, Spanish- and/or indigenous-language speaking; countries of origin; level of “outness”); the theoretical foundations; and intervention themes, strategies, and objectives. This Step initiated creative thinking about the intervention to build on the state of both the science and practice of sexual health promotion among Latino MSM in the US.

Step 4: Explore health-related needs and priorities of Latino MSM

We initiated several actions to identify health-related needs and priorities. First, the partnership conducted ethnographic interviews with 21 Latino MSM ages 18-48 years old. Findings have been reported elsewhere (Rhodes, Hergenrather, et al., 2010); analyses of these interviews suggested that Latino MSM prioritized sexual health; Latino MSM lacked accurate information about sexual health and disease prevention; social and political contexts contributed to sexual risk (e.g., manhood can be affirmed through sex and risk; distrust of US healthcare system, providers, and the confidentiality of medical records); and barriers existed to accessing and utilizing healthcare services (e.g., lack of knowledge about available services and eligibility, sense of fatalism).

The Intervention Team identified potential intervention needs and approaches, including: filling knowledge gaps; building on informal peer-based networks; providing safe spaces for facilitated group dialogue around issues of: living with HIV, meanings and expressions of love and intimacy, successful approaches to “negotiating” safer sex particularly within relationships with power imbalances (e.g., well-resourced versus less well-resourced partner, white versus Latino partner, more English-speaking versus less English-speaking partner); offering positive social outlets; providing guidance on eligibility and how to access healthcare resources (including, HIV and STD testing, and free condoms); addressing masculinity; and advocacy training.

Concurrently, the partnership completed a respondent-driven sampling (RDS) study of 190 Latino MSM. Data indicated that Latino MSM had low levels of knowledge about HIV and STD transmission, prevention, and treatment; high levels of adherence to traditional notions of masculinity; and high internalized homonegativity. Latino MSM also had low rates of condom use and use of healthcare services for which they were eligible (e.g., HIV and STD screening). Prevalence estimates of heavy episodic drinking within the past 30 days was 35%, and prevalence of marijuana and cocaine use within the past 12 months were 56% and 27%, respectively (Rhodes et al., 2012).

To develop preliminary intervention priorities, members of the Intervention Team used findings from the interviews, the RDS study, and from other local studies conducted by the partnership (Rhodes, Fernandez, et al., 2011; Rhodes et al., 2009; Rhodes, Hergenrather, et al., 2011; Rhodes, McCoy, et al., 2011; Rhodes, Vissman, et al., 2011; Rhodes, Yee, et al., 2006; Vissman, Bloom, et al., 2011; Vissman et al., 2009; Vissman, Hergenrather, et al., 2011).

Step 5: Refine and narrow intervention priorities

The partnership used a nominal group process (Becker, Israel, & Allen, 2005) to finalize intervention priorities, five community forums were held, each with between two and ten Latino MSM in addition to other community members, organizational representatives, and academic researchers. We convened these forums in convenient and safe locations, including a private room within a restaurant of a truck stop, a community leader’s home, and a Latino restaurant. The finalized intervention priorities were:

Increase awareness of the magnitude of HIV and STD infection;

Provide information on types of infections, modes of transmission, and signs and symptoms;

Offer guidance on local counseling, testing, care, and treatment services, eligibility requirements, and “what to expect” in healthcare encounters;

Build condom use skills (e.g., how to communicate effectively, how to properly select, use, and dispose of condoms);

Change health-compromising norms of what it means to be an immigrant, a Latino man, a gay man, and an MSM;

Build supportive relationships and sense of community; and

Provide skills-building to successfully help others.

During this Step, Intervention Team members concluded that training Latino MSM within the community to serve as LHAs built upon existing social support activities in which Latino MSM naturally were engaged (e.g., providing transportation, a place to live, support to find a job, advice). The partnership also concluded that an LHA approach had the potential to effectively and efficiently reach large numbers of Latino MSM, particularly given that Latino MSM may be hard-to-reach by “outsiders” (e.g., non-Latinos) because of the stigma around immigration and same-sex orientation and behavior.

Step 6: Blend health behavior theory with the lived experiences of Latino MSM

Behavioral theory helped Intervention Team members understand the mechanisms that existing interventions used to promote positive change in knowledge, attitudes, and/or behaviors. Because theory is intended to explain the processes involved in behavior change, understanding theory and integrating theory with perspectives on immigrant Latino MSM lived experiences were crucial for the Intervention Team to make informed decisions about intervention strategies and activities. The Intervention Team determined that, in addition to the LHA approach, application of both social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986) and empowerment education (Freire, 1973) would be used to frame the intervention and strengthen the informal social and helping networks among Latino MSM, thus increasing its potential success.

Step 7: Design of an intervention conceptual model

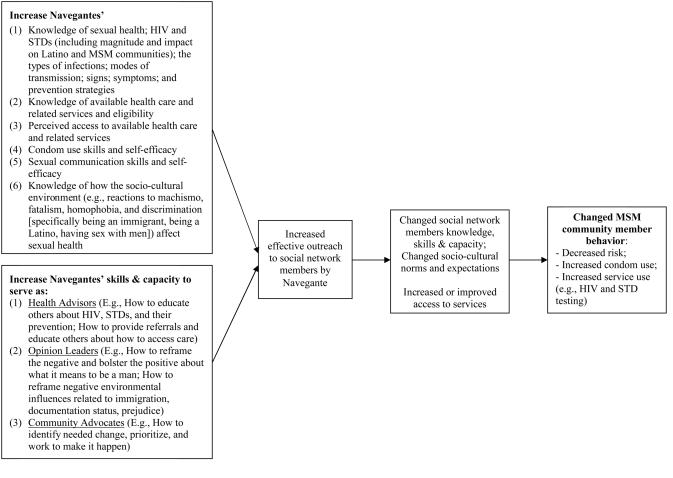

Developed by the Intervention Team through iterative feedback from the partnership, the resulting HOLA intervention conceptual model demonstrated how each LHA (known as a Navegante [Navigator]) would increase knowledge, health-promoting attitudes, and skills among Latinos MSM within the community through three primary roles: health advisors, opinion leaders, and community advocates. The conceptual model is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

HOLA conceptual model

Step 8: Develop training modules

Intervention Team members drafted, adapted, reviewed, and revised each HOLA intervention Module used to train Navegantes. They developed a general outline of the Modules including: its goal, objectives, key messages, and theoretical underpinnings. Intervention activities were then outlined and developed. They followed an iterative process with multiple opportunities for Intervention Team and partnership members to provide feedback.

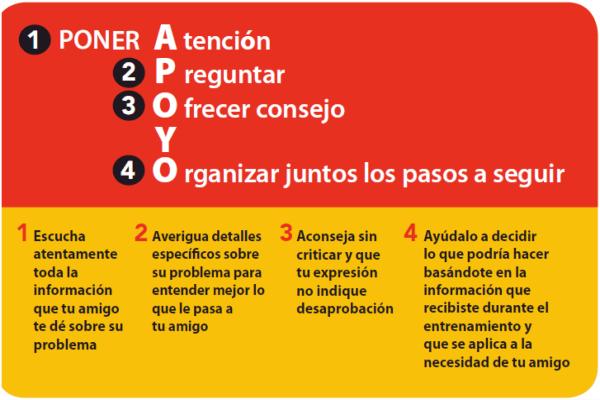

Step 9: Develop materials

After developing the intervention, we created materials, including a low-literacy wallet-sized reminder that serves as a “cheat sheet” for Navegantes on how to provide support to others using the partnership-developed APOYO (“help”) model that stands for: “poner Atención”-“Preguntar”-“Ofrecer consejo”-“Y”-“Organizar juntos los pasos siguientes” (pay attention-ask questions-offer advice-and-together organize next steps). The APOYO card is provided in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

The Wallet-Sized APOYO Card for Navegantes

We developed other materials including: role-playing scripts and process evaluation data collection forms that serve as a cue for LHA activities and are used to document the help that Navegantes provide. We also developed DVD scenes based in the success we had with scenes in the HoMBReS-2 intervention. These DVD scenes use community members as actors, serve as triggers for discussion, and provide role modeling to build self-efficacy and communication skills (Rhodes, McCoy, et al., 2011). These DVD scenes are embedded into the training of the Navegantes. Further, three of these scenes were designed for use by Navegantes with their social networks of MSM (in groups and individually): initiating correct condom use with a same-sex partner; how to get tested for HIV at local health departments; and living with HIV as a Latino gay man.

A partnership member also identified a segment from an English-language online prevention campaign that used gay porn actors to teach MSM how to correctly use condoms and water-based lubricants using their own body parts (as opposed to penis models or bananas); he proposed that the scene be used in the HOLA intervention. The Intervention Team showed the segment featuring the porn actors to Latino MSM within the community to gauge appeal versus embarrassment or offense. Because the segment was highly appealing to Latino MSM, the Intervention Team obtained permission to embed the segment (dubbed in Spanish) into a longer and more comprehensive HOLA intervention DVD scene. The developed scene follows two Latino gay men as they meet in a local gay bar, go home together, and deal with commonly heard misconceptions about transmission and prevention that we identified within our formative research (e.g., insertive partner cannot get HIV or an STD; if a partner looks healthy and is fit, he cannot be infected). In a final attempt to persuade one of the men to use a condom, the other gets a laptop and the two men watch as the two porn actors describe and model how to correctly use a condom.

Steps 10 and 11: Pretest and revise the intervention

The HOLA intervention activities were pretested by male Spanish-speaking members of the Intervention Team with lay community members. Revisions were made to the intervention activities based on this pretesting that garnered extensive feedback.

Results

The HOLA intervention, developed by the CBPR partnership, provides a comprehensive four-Module training for Navegantes. The Modules and abbreviated learning objectives are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

HOLA Training Modules and Abbreviated LHA Learning Objectives

| Module Title (4 hours each): |

Objectives: At the completion of the Module, participants will be able to: |

|---|---|

| (1) General information about the program and an introduction to sexual health |

Explain the goals of the HOLA intervention Describe the magnitude of HIV and STDs among Latinos and Latino MSM Explain Navegante roles and responsibilities Identify the most common STDs, their symptoms, and treatment Differentiate between lower and higher risk behaviors Describe two different ways to use environmental cues to steer conversations towards HIV prevention |

| (2) Protecting Yourself and Your Partners |

Outline the sequential steps for correct male and female condom use Identify common facilitators and barriers to condom use Apply effective communication techniques to reframe negative and bolster positive perceptions about condom use Evaluate the pros and cons of four different types of male condoms and the female condom |

| (3) Cultural Values that Affect Our Health |

List Latino cultural values that affect the health of Latino MSM Describe reciprocal determinism and apply it to the sexual health of Latino gay men Reframe three negative attitudes that affect Latino gay men’s health Reframe three negative attitudes that prevent Latino gay men from seeking healthcare services Explain the process of seeking public health services Describe the steps of the APOYO model |

| (4) Review/Bringing it all together |

Apply the APOYO model Distinguish between HIV and STD myths and realities Describe what it is like to be a Latino gay man living with HIV Define and list the pros and cons of abstinence as a method to prevent HIV and STDs Outline why evaluation is important List the evaluations to be completed Outline how to complete the Activity Logs Describe how the “theme of the month” is conducted |

Module 1 introduces Navegantes to the intervention and sexual health; the impact of HIV on Latino communities; and the roles and responsibilities of Navegantes. In Module 2, Navegantes increase their knowledge of HIV and STD prevention strategies, the correct use of male and female condoms, and how to communicate with others about condom use, specifically how to reframe negative and bolster positive perceptions about condom use among MSM to become effective opinion leaders. In Module 3, Navegantes expand on their growing knowledge of the factors that influence health focusing on cultural expectations, explore cultural values, and learn how reciprocal determinism, a construct of social cognitive theory, affects the health of Latino MSM. They learn the process of seeking public health department services and getting testing for HIV and STDs. They also practice using the APOYO model to develop their communication skills. In Module 4, Navegantes review information and skills provided and further practice skills taught during their training, learn about what it is like to live with HIV as a Latino MSM, and discuss abstinence. They also learn about the activities that will be conducted to evaluate the intervention. At the conclusion of Module 4, Navegantes receive recognition for their accomplishments during a graduation ceremony signifying initiation of their official roles as Navegantes.

After completing their training, Navegantes work with other Latino MSM within their existing informal social networks (both one-on-one and in small groups). As health advisors, Navegantes provide information and resources. For example, a social network member may hesitate to seek HIV testing because he does not speak English. In this instance, Navegantes may describe how to overcome this barrier when entering the health department, e.g., that eventually, an interpreter will be available or staff will work with them to schedule a time when an interpreter is available. In another example, Navegantes teach self-protective skills and have penis models and condoms to teach proper condom use skills. As opinion leaders, Navegantes learn to reframe negative and bolster positive norms and expectations about being a Latino MSM. Navegantes are taught how norms and expectations are reinforced and about their own role in changing those that are health compromising and reinforcing those that are health promoting. Third, Navegantes serve as community advocates by bringing the voices of immigrant Latinos and MSM to the partnership and to agencies that offer health services.

Although much of the work that LHAs do is often based on their informal provision of social support (Eng, Rhodes, & Parker, 2009; Rhodes, Eng, et al., 2007; Rhodes, Foley, Zometa, & Bloom, 2007; Rhodes et al., 2009; Vissman et al., 2009), the Intervention Team developed multiple 60- to 90- minute prescribed group sessions that each Navegante implements within his social network. The initial meeting establishes each Navegante’s role as an LHA within his social network and legitimizes his role in the presence of Intervention Team members. At subsequent meetings Navegantes teach Latino MSM about the correct use of condoms; lead a discussion to brainstorm and overcome communication barriers with sexual partners (e.g., how to discuss condom use); review the process of HIV testing at the local health department to demystify the process and illustrate how challenges can be surmounted; show the DVD about living with HIV and facilitate a discussion about living with HIV; and facilitate dialogue to explore what it is like being an immigrant Latino MSM in the US through discussions designed to build positive self-images and further supportive and healthy relationships.

The HOLA intervention also includes monthly group meetings for Navegantes to discuss implementation successes and challenges, provide social support to one another, plan supplemental activities, share experiences, and resolve problems.

Discussion

The HOLA intervention fills a critical gap. Currently, there are few efficacious HIV prevention interventions for MSM and no published intervention that has been found efficacious for Latino MSM. This intervention is unique because it: is designed specifically for immigrant Spanish-speaking Latino MSM, who tend to be recently arrived, have not been exposed to HIV prevention outreach efforts in their countries of origin, and have low levels of acculturation and limited perceived access to healthcare services; is a community-level intervention that addresses cultural values and builds on community assets, including natural helpers and the existence of informal social networks; has the potential to impact large numbers of Latino MSM, which is particularly important given the growth rate of the epidemic within the highly vulnerable Latino community; and fulfills a need for early intervention before visits to an STD clinic are warranted.

Furthermore, the HOLA intervention is designed to build community capacity by training Latino MSM to help their own community through skills development. Navegantes develop leadership, and public speaking and community mobilization skills, which may be transferable to other health issues (Vissman et al., 2009). Given that HIV and STDs are among a multitude of health challenges disproportionately affecting Latinos, interventions that develop capacity are paramount to addressing the broader set of health disparities experienced by vulnerable and neglected populations. LHA interventions may become increasingly important given anti-immigration sentiment in NC and throughout the US that discourages Latinos from seeking services which they need and for which they are eligible (Rhodes, Eng, et al., 2007; Vissman, Bloom, et al., 2011).

Refining a process that the partnership used previously to develop evidence-based interventions (Rhodes et al., 2009; Rhodes, Hergenrather, et al., 2006; Rhodes, McCoy, et al., 2011; Rhodes, Vissman, et al., 2011), partnership members blended the real lived experiences of Latino MSM, sound behavioral theory, and locally collected formative research to develop an intervention that is being implemented and evaluated at this writing. The intervention also contains elements that effective HIV prevention interventions share, including incorporating locally collected data and tailoring to a defined audience; being gender specific; having a solid theoretical foundation; incorporating discussions of barriers to, and facilitators of, sexual health; exploring gender norms and expectations; increasing self-esteem and group pride; increasing risk reduction norms and social support for protection; building skills to perform technical, personal, or interpersonal skills through role plays and practice; and offering guidance on how to utilize available services (Herbst et al., 2007; Huedo-Medina et al., 2010; Lyles, Crepaz, Herbst, & Kay, 2006; Lyles et al., 2007; Rhodes, McCoy, et al., 2011).

Blending the perspectives of community members, organizational representatives, and academic researchers through authentic CBPR may yield more successful interventions, yet there is little guidance on how to develop interventions using CBPR. Our partnership developed a systematic approach to intervention development that can be applied to other communities and populations, and other health issues by CBPR partnerships and practitioners. Given the persistence of racial/ethnic health disparities–in HIV as well as other health outcomes–this systematic process offers an innovative approach to intervention development and refinement in general, and through CBPR in particular.

References

- Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall; Englewood Cliffs: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Becker AB, Israel BA, Allen AJ. Strategies and techniques for effective group process in CBPR partnerships. In: Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, editors. Methods in Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 2005. pp. 52–72. [Google Scholar]

- Cashman SB, Adeky S, Allen AJ, Corburn J, Israel BA, Montaño J, Eng E. The power and the promise: working with communities to analyze data, interpret findings, and get to outcomes. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(8):1407–1417. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.113571. doi: AJPH.2007.113571 [pii] 10.2105/AJPH.2007.113571 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . HIV surveillance report. Vol. 22. US Department of Health and Human Services; Atlanta: 2012. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Eng E, Moore KS, Rhodes SD, Griffith D, Allison L, Shirah K, Mebane E. Insiders and outsiders assess who is "the community": participant observation, key informant interview, focus group interview, and community forum. In: Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker E, editors. Methods for Conducting Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 2005. pp. 77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Eng E, Rhodes SD, Parker EA. Natural helper models to enhance a community's health and competence. In: DiClemente RJ, Crosby RA, Kegler MC, editors. Emerging Theories in Health Promotion Practice and Research. Vol. 2. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 2009. pp. 303–330. [Google Scholar]

- Freire P. Seabury Press; New York, NY: 1973. Education for critical consciousness. [Google Scholar]

- Herbst JH, Kay LS, Passin WF, Lyles CM, Crepaz N, Marin BV. A systematic review and meta-analysis of behavioral interventions to reduce HIV risk behaviors of Hispanics in the United States and Puerto Rico. AIDS & Behavior. 2007;11(1):25–47. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9151-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huedo-Medina TB, Boynton MH, Warren MR, Lacroix JM, Carey MP, Johnson BT. Efficacy of HIV prevention interventions in Latin American and Caribbean nations, 1995-2008: a meta-analysis. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(6):1237–1251. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9763-3. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9763-3 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB, Allen AJ, Guzman R. Critical issues in developing and following community based participatory research issues. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 2003. pp. 53–76. [Google Scholar]

- Jones KT, Gray P, Whiteside YO, Wang T, Bost D, Dunbar E, Johnson WD. Evaluation of an HIV prevention intervention adapted for Black men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(6):1043–1050. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.120337. doi: AJPH.2007.120337 [pii] 10.2105/AJPH.2007.120337 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kegeles SM, Hays RB, Coates TJ. The Mpowerment Project: a community-level HIV prevention intervention for young gay men. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86(8):1129–1136. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.8_pt_1.1129. Pt 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyles CM, Crepaz N, Herbst JH, Kay LS. Evidence-based HIV behavioral prevention from the perspective of the CDC's HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis Team. AIDS Education & Prevention. 2006;18(4 Suppl A):21–31. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.supp.21. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.supp.21 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyles CM, Kay LS, Crepaz N, Herbst JH, Passin WF, Kim AS, Mullins MM. Best-evidence interventions: findings from a systematic review of HIV behavioral interventions for US populations at high risk, 2000-2004. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(1):133–143. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.076182. doi: AJPH.2005.076182 [pii] 10.2105/AJPH.2005.076182 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Improving health education through community building organization and community building: a health education perspective. In: Minkler M, editor. Community Organizing and Community Building for Health. Rutgers University Press; New Brunswick, NJ: 2002. pp. 30–52. [Google Scholar]

- North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services New estimates profile new HIV infections in North Carolina. 2008 Retreived from: http://www.dhhs.state.nc.us/pressrel/2008/2008-9-12-New-estimates-profile-new-HIV.htm.

- North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services . NC Department of Health and Human Services; Raleigh, NC: 2010. 2009 HIV/STD surveillance report. [Google Scholar]

- North Carolina State Center for Health Statistics Behavioral risk factor surveillance system (BRFSS) 2006 Retrieved from: http://www.schs.state.nc.us/SCHS/brfss.

- Rausch D, Dieffenbach C, Cheever L, Fenton KA. Towards a more coordinated federal response to improving HIV prevention and sexual health among men who have sex with men. AIDS & Behavior. 2011;15(Suppl 1):S107–111. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9908-z. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9908-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD. Demonstrated effectiveness and potential of CBPR for preventing HIV in Latino populations. In: Organista KC, editor. HIV Prevention with Latinos: Theory, Research, and Practice. Oxford University Press; (In press) [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Duck S, Alonzo J, Downs M, Aronson RE. The role and utility of community-based participatory research in intervention trials. In: Blumenthal D, DiClemente RJ, Braithwaite RL, Smith S, editors. Community-Based Participatory Research: Issues, Methods, and Translation to Practice. Springer; New York: (In press) [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Eng E, Hergenrather KC, Remnitz IM, Arceo R, Montano J, Alegria-Ortega J. Exploring Latino men's HIV risk using community-based participatory research. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2007;31(2):146–158. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2007.31.2.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Fernandez FM, Leichliter JS, Vissman AT, Duck S, O'Brien MC, Bloom FR. Medications for sexual health available from non-medical sources: A need for increased access to healthcare and education among immigrant Latinos in the rural southeastern USA. Journal of Immigrant & Minority Health. 2011;13:1183–1186. doi: 10.1007/s10903-010-9396-7. doi: 10.1007/s10903-010-9396-7 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Foley KL, Zometa CS, Bloom FR. Lay health advisor interventions among Hispanics/Latinos: A qualitative systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;33(5):418–427. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC, Aronson RE, Bloom FR, Felizzola J, Wolfson M, McGuire J. Latino men who have sex with men and HIV in the rural south-eastern USA: findings from ethnographic in-depth interviews. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2010;12(7):797–812. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2010.492432. doi: 923339233 [pii] 10.1080/13691058.2010.492432 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC, Bloom FR, Leichliter JS, Montaño J. Outcomes from a community-based, participatory lay health advisor HIV/STD prevention intervention for recently arrived immigrant Latino men in rural North Carolina, USA. AIDS Education & Prevention. 2009;21(Supplement 1):104–109. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.5_supp.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC, Montano J, Remnitz IM, Arceo R, Bloom FR, Bowden WP. Using community-based participatory research to develop an intervention to reduce HIV and STD infections among Latino men. AIDS Education & Prev. 2006;18(5):375–389. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.5.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC, Vissman AT, Stowers J, Davis AB, Hannah A, Marsiglia FF. Boys must be men, and men must have sex with women: A qualitative CBPR study to explore sexual risk among African American, Latino, and white gay men and MSM. American Journal of Men's Health. 2011;5(2):140–151. doi: 10.1177/1557988310366298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Malow RM, Jolly C. Community-based participatory research: a new and not-so-new approach to HIV/AIDS prevention, care, and treatment. AIDS Education & Prevention. 2010;22(3):173–183. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2010.22.3.173. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2010.22.3.173 [doi] 10.1521/aeap.2010.22.3.173 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, McCoy TP, Hergenrather KC, Vissman AT, Wolfson M, Alonzo J, Eng E. Prevalence estimates of health risk behaviors of immigrant Latino men who have sex with men. Journal of Rural Health. 2012;28(1):73–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2011.00373.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, McCoy TP, Vissman AT, DiClemente RJ, Duck S, Hergenrather KC, Eng E. A randomized controlled trial of a culturally congruent intervention to increase condom use and HIV testing among heterosexually active immigrant Latino men. AIDS & Behavior. 2011;15(8):1764–1775. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9903-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Vissman AT, Stowers J, Miller C, McCoy TP, Hergenrather KC, Eng E. A CBPR partnership increases HIV testing among men who have sex with men (MSM): outcome findings from a pilot test of the CyBER/testing Internet intervention. Health Education & Behavior. 2011;38(3):311–320. doi: 10.1177/1090198110379572. doi: 1090198110379572 [pii] 10.1177/1090198110379572 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Yee LJ, Hergenrather KC. A community-based rapid assessment of HIV behavioural risk disparities within a large sample of gay men in southeastern USA: a comparison of African American, Latino and white men. AIDS Care. 2006;18(8):1018–1024. doi: 10.1080/09540120600568731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vissman AT, Bloom FR, Leichliter JS, Bachmann LH, Montaño J, Topmiller M, Rhodes SD. Exploring the use of nonmedical sources of prescription drugs among immigrant Latinos in the rural southeastern USA. Journal of Rural Health. 2011;27(2):159–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2010.00323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vissman AT, Eng E, Aronson RE, Bloom FR, Leichliter JS, Montaño J, Rhodes SD. What do men who serve as lay health advisors really do?: Immigrant Latino men share their experiences as Navegantes to prevent HIV. AIDS Education & Prevention. 2009;21(3):220–232. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.3.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vissman AT, Hergenrather KC, Rojas G, Langdon SE, Wilkin AM, Rhodes SD. Applying the theory of planned behavior to explore HAART adherence among HIV-positive immigrant Latinos: Elicitation interview results. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85(3):454–460. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.12.004. doi: S0738-3991(10)00743-3 [pii] 10.1016/j.pec.2010.12.004 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Oetzel J, Duran B, Tafoya G, Belone L, Rae R. What predicts outcomes in CBPR? In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-Based Participatory Research: From Process to Outcomes. Wiley; San Francisco, CA: 2008. pp. 371–392. [Google Scholar]