Abstract

Honey could be considered the most sustainable food produced naturally. It contains sugars, vitamins, minerals and has high anti-oxidant activities. Cancer is on the rise in most countries. Carcinogenesis is a multi-step process and has multi-factorial causes. Among these are low immune status, chronic infection, chronic inflammation, chronic nonhealing ulcers, smoking, obesity etc. Published studies thus far have shown that honey improves immune status, has anti-inflammatory and anti-microbial properties and promotes healing of chronic ulcers and wounds and scavenge toxic free radicals. Recently honey has been shown to have anti-cancer properties in cell cultures and in animal models. The mechanisms suggested include induction of apoptosis, disruption of mitochondrial membrane potential and cell cycle arrest. Though sugar is predominant in honey which itself is thought to be carcinogenic, it is understandable that its beneficial effect as anti-cancer agent raises skeptics. With increasing number of people seeking therapy from nature, this area of research has recently gained attention.

Keywords: Honey, Cancer, Immune booster, Anti-inflammatory, Anti-microbial, Scavengers of toxic free radicals

Cancer – the Global Burden

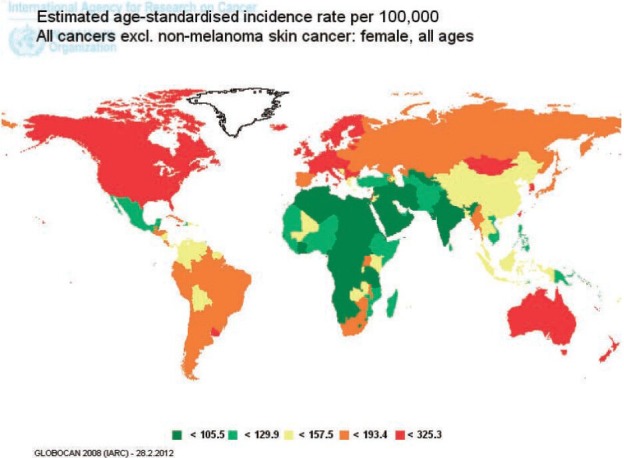

Cancer is a global epidemic. In 2008, it was estimated there were 12,332,300 cancer cases of which 5.4 million were in developed countries and 6.7 millions were in developing countries (Garcia et al., 2007) (Figure 1). The increase in populations was much more in developing countries than in developed countries. Even if the age-specific rates of cancer remain constant, developing countries would have a higher cancer burden than developed countries.

Figure 1.

Estimated new cancer cases by world arease (source: Globocan, 2008)

Cancers which are associated with diet and life-style are seen more in developed countries while cancers which are due to infections are more in developing countries. According to World Health Organization (WHO), death from cancer is expected to increase to 104% worldwide by 2020.

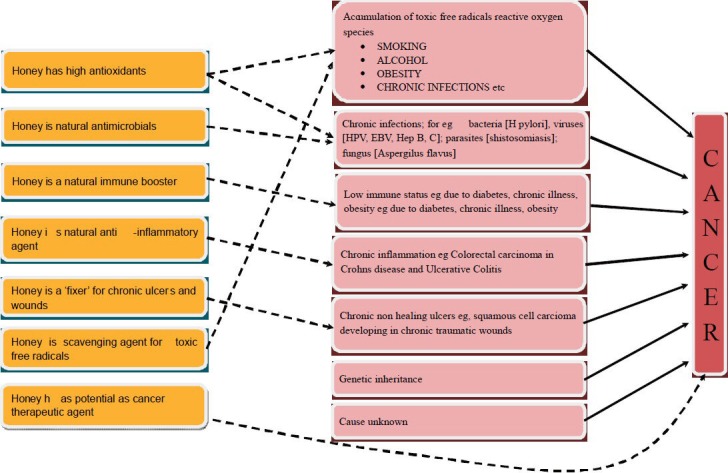

Figure 2.

The diagrammatic relationship of honey and cancer (Key: soild line (→): arallel relationship; dotted line (→): inverse relationship

In order to understand the usefulness of honey in cancer, we need to understand the various factors which could cause cancer. Carcinogenesis is a multi-step process and cancer has multi-factorial causes. Development of cancers takes place long after initiation, promotion and progression steps have taken place. Cancer development could occur 10-15 years after exposure to the risk factors.

Causes of Cancer:

The causes of cancer can be categorized as follows:-

Low immune status eg due to diabetes, chronic illness, obesity and old age

Chronic infections such as by bacteria helicobater pylori (cancer of the stomach), viruses such as Human Papiloma Virus (cancer of the cervix, skin and penis), Epstein Barr Virus (nasopharyngeal carcinoma), Hepatitis viruses such as Hepatitis B, C (hepatocellular carcinoma); parasites such as shistosomiasis (bladder cancer) and fungus such as Aspergilus flavus (hepatocellular carcinoma)

Chronic inflammation, for example colorectal cancer developing in patients with Crohns colitis and ulcerative colitis.

Chronic non healing ulcers, for example squamous cell carcinoma developing in patients with chronic traumatic ulcers of the skin.

Accumulation of toxic free radicals and oxidative stress secondary to smoking, alcohol, obesity and chronic inflammatory processes

Genetic inheritance

Unknown – there is still a lot we do not know

Cancer is caused by genetic damage in the genome of cells. This damage is either inherited or acquired throughout life. The acquired genetic damage is often ‘self-inflicted’ through unhealthy lifestyles. Broadly one third of cancer is due to tobacco use, one third due to dietary and lifestyle factors and one-fifth due to infections. In developing countries, cancers caused by infections by micro-organisms such as cervical (by Human Papilloma Virus) (Parkin et al., 2008), liver (by Hepatitis Viruses) (Yuen et al., 2009), nasopharynx (by Epstein Barr Virus) (Chou et al., 2008) and stomach (by helicobacter pylori) (Kuniyasu et al., 2003) are more common than in developed countries (DCP2, 2007). Except for breast cancers, the top 5 cancers in males and females in developing nations are due to life-styles or infections (DCP2, 2007).

Why is Honey Useful in Preventing Cancer?

Honey is known for centuries for its medicinal and health promoting properties. It contains various kinds of phytochemicals with high phenolic and flavonoid content which contribute to its high antioxidant activity (Iurlina et al., 2009; Pyrzynska and Biesaga, 2009; Yao et al., 2003). Agent that has strong antioxidant property may have the potential to prevent the development of cancer as free radicals and oxidative stress play a significant role in inducing the formation of cancers (Valko et al., 2007). Phytochemicals available in honey could be narrowed down into phenolic acids and polyphenols. Variants of polyphenols in honey are reported to have anti-proliferative property against several types of cancer (Jaganathan and Mahitosh, 2009).

The scientific evidence on why honey could be a natural cancer vaccine

Honey is a natural immune booster

Honey stimulates antibody production during primary and secondary immune responses against thymus-dependent and thymus-independent antigens in mice injected with sheep red blood cells and E-coli antigen (Al-Waili and Haq, 2004). Oral intake of honey augments antibody productions in primary and secondary immune responses (Fukuda et al., 2009). Honey also stimulates inflammatory cytokine production from monocytes (Tonks et al., 2003) via TLR4 (Tonks et al., 2007). Manuka, pasture and jelly bush honey significantly increased TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 release from MM6 cells (and human monocytes) when compared with untreated and artificial-honey-treated cells (P <0.001) (Tonks et al., 2003). Consumption of 80 g natural honey for 21 days raised prostaglandins level in patients with AIDS compared with normal subjects (Al-Waili et al., 2006).

Patients who have low immune system are at risk for cancer development. This explains why diabetics and HIV patients are more at risk to develop epithelial and non epithelial cancers. Such individuals are also at risk to develop multiple chronic infections implying the multiplicity in cancer genesis.

Aging is also associated with reduced immune system. Many cancers are associated with aging. Although age per se is not an important determinant of cancer risk, it implies prolonged exposure to carcinogen (Franceschi and La Vecchia, 2001). The most important change that would occur in the world population in the next 50 years is the change in the proportion of elderly people (more than 65 years); 7% in 2000 to 16% in 2050 (Bray and Moller, 2006). By the year 2050, 27 million people are projected to have cancer. More than half of the estimated number will be residents of developing countries (Bray and Moller, 2006). Improvement in immune status is key in prevention of cancer formation and honey has such potential.

Honey is a natural anti-inflammatory agent

In general inflammatory responses are beneficial, but at times, chronic inflammatory responses are detrimental to health. Honey is a potent anti-inflammatory agent. Infants suffering from diaper dermatitis improved significantly after topical application of a mixture containing honey, olive oil and beeswax after 7 days (Al-Waili, 2005). Honey provides significant symptom relief of cough in children with upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) (Heppermann, 2009). It has been shown to be effective in management of dermatitis and psoriasis vulgaris (Al-Waili, 2003). Eight out of 10 patients with dermatitis and five of eight patients with psoriasis showed significant improvement after 2 weeks on honey-based ointment (Al-Waili, 2003). A case report of a patient who had chronic dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (EB) for 20 years healed with honey impregnated dressing in 15 weeks after conventional dressings and creams failed (Hon, 2005). Local application of raw honey on infected wounds reduced signs of acute inflammation (Al-Waili, 2004b), thus alleviating pain felt by patients.

Volunteers who chewed “honey leather” showed there were statistically highly significant reductions in mean plaque scores (0.99 reduced to 0.65; p=0.001) in the manuka honey group compared to the control group suggesting a potential therapeutic role of honey for gingivitis, periodontal disease (English et al., 2004), mouth ulcers, and other problems of oral health (Molan, 2001b).

Chronic inflammatory process has risk of cancer development. Examples of cancers developing in patients suffering from chronic inflammatory processes include colorectal carcinomas developing in patients with Ulcerative Colitis and Chron's disease and thyroid cancers in patients with autoimmune thyroiditis.

Honey is natural antimicrobials

Honey is a potent natural antimicrobial. Antibacterial effect of honey is extensively studied. The bactericidal mechanism is through disturbance in cell division machinery (Henriques et al., 2009). The minimum inhibitory concentration (MICs) for Staphylococcus aureus by honey ranged from 126.23 to 185.70 mg ml(-1) (Miorin et al., 2003). Honey is also effective against coagulase-negative staphylococci(French et al.,2005). Antimicrobial activity of honey is stronger in acidic media than in neutral or alkaline media (Al-Waili, 2004b). When honey is used together with antibiotic gentamycin, it enhances anti-Staphylococcus aureus activity by 22% (Al-Jabri et al., 2005). When honey is added to bacterial culture medium, the appearance of microbial growth on the culture plates is delayed (Al-Waili et al., 2005). Mycobacteria did not grow in culture media containing 10% and 20% honey while it grew in culture media containing 5%, 2.5% and 1% honey, suggesting that honey could be an ideal antimycobacterial agent (Asadi-Pooya et al., 2003) at certain concentrations.

Honey is also effective in killing hardy bacteria such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa and could lead to a new approach in treating refractory chronic rhino-sinusitis (Alandejani et al., 2009). Daily consumption of honey reduces risk of chronic infections by micro-organisms.

Chronic infections have risk for cancer development. Bacteria which have been studied to have associations with cancer are helicobater pylori infections (stomach cancer) (Kuniyasu et al., 2003), Ureaplasma urealyticum (prostate cancer) (Hrbacek et al., 2011) and chronic typhoid infection (gall bladder cancer) (Sharma et al., 2007).

There are three main mechanisms by which infections can cause cancer. They appear to involve initiation as well as promotion of carcinogenesis (Kuper et al., 2001). Persistent infection within host induce chronic inflammation accompanied by formation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS and RNOS) (Kuper et al., 2001). ROS and RNOS have the potential to damage DNA, proteins and cell membranes. Chronic inflammation often results in repeated cycles of cell damage leading to abnormal cell proliferation (Cohen et al., 1991). DNA damage promotes the growth of malignant cells. Secondly, infectious agents may directly transform cells, by inserting active oncogenes into the host genome, inhibiting tumour suppressors (Kuper et al., 2001). Thirdly, infectious agents, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), may induce immunosuppression (Kuper et al., 2001).

Chronic fungi infections have also been studied to be associated with cancer such as candida species in oral cancer (Hooper et al., 2009). Honey has been shown to have some effect on chronic fungal infections of the skin (Al-Waili, 2004a). Parasites such as Schistosoma haematobium are associated with carcinoma of the urinary bladder, liver flukes Opisthorchis viverrini and Clonorchis sinensis are associated with development of cholangiocarcinoma and hepatocellular carcinoma. Thus far, there are no published reports on effect of honey on parasitic diseases.

Besides bacteria, honey also has been shown to have anti-viral properties. In a comparative study, topical application of honey was found to be better than acyclovir treatment on patients with recurrent herpetic lesions (Al-Waili, 2004c). Two cases of labial herpes and one case of genital herpes remitted completely with the use of honey while none with acyclovir treatment (Al-Waili, 2004c).

Common viruses which cause cancers (Carrillo-Infante et al., 2007) are Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) (Siddique et al., 2010) (nasopharyngeal carcinomas), Human Papilloma Virus (cervical cancers and other squamous cancers) and Hepatitis B viruses (liver cancers). Viruses are oncogenenic after long period of latency (McLaughlin-Drubin and Munger, 2008). Studies on the effect of honey on these specific viruses are required to affirm the usefulness of honey in combating cellular damage caused by these virues.

Honey is a scavenging agent of toxic free radicals

Association of cancer to cigarette smoking is beyond doubt. It is due to generations of toxic free radicals and oxidative stress. Smoking is associated with a number of cancers such as larynx, bladder, breasts, oesophagus and cervix. Smoking increases the risk of colorectal carcinomas by 43% (Huxley, 2007). Ever-smokers were associated with an 8.8-fold increased risk of colorectal cancers (95% confidence interval, 1.7-44.9) when fed on well-done red meat diet if they have NAT2 and CYP1A2 rapid phenotypes (Le Marchand et al., 2001).

Antioxidants, abundant in natural honey, are free-radical scavengers (Kishore et al., 2011). Jungle honey was shown to have chemotactic induction for neutrophils and reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Fukuda et al., 2009). The amino acid composition of honey is an indicator of the toxic radical scavenging capacity (Perez et al., 2007). The antioxidant activity of Trigona carbonaria honey from Australia is high at 233.96 +/-50.95 microM Trolox equivalents (Oddo et al., 2008). Dark honey had higher phenolic compounds and anti-oxidant activity than clear honey (Estevinho et al., 2008). Some simple and polyphenols found in honey, namely, caffeic acid (CA), caffeic acid phenyl esters (CAPE), Chrysin (CR), Galangin (GA), Quercetin (QU), Kaempferol (KP), Acacetin (AC), Pinocembrin (PC), Pinobanksin (PB), and Apigenin (AP), have evolved as promising pharmacological agents in prevention of cancer (Jaganathan and Mandal, 2009).

Honey is ‘fixer’ for chronic ulcers and wounds

Increasing numbers of antibiotic-resistant bacteria has made simple wounds become chronic and non-healing and as such honey provides alternative treatment options (Sharp, 2009). Honey absorbs exudates released in wounds and devitalized tissue (Cutting, 2007). Honey is effective in recalcitrant surgical wounds (Cooper et al., 2001). It increases the rate of healing by stimulation of angiogenesis, granulation, and epithelialization (Molan, 2001a). In a randomized control trial, Manuka honey improved wound healing in patients with sloughy venous leg ulcers (Armstrong, 2009). Honey was shown to eradicate MRSA (Methylene resistant Staphyloccus aureaus) infection in 70% of chronic venous ulcers (Gethin and Cowman, 2008). Honey is acidic and chronic non healing wounds have an elevated alkaline environment. Manuka honey dressings is associated with a statistically significant decrease in wound Ph (Gethin et al., 2008).

Chronic ulcers have risk to develop cancer. The most common is Marjolin's ulcer (Asuquo et al., 2009) and they are common in developing nations especially in rural areas with poor living conditions (Asuquo et al., 2007). This risk factor is related to chronic infections as most if not all chronic ulcers are non-healing because of persistent infections.

Honey is a potential agent for controlling obesity

Obese individuals are at risk to develop cancer. There is a close link among obesity, a state of chronic low-level inflammation, and oxidative stress (Codoner-Franch et al., 2011). Obese subjects have an approximately 1.5-3.5-fold increased risk of developing cancers compared with normal-weight subjects (Pischon et al., 2008), (Rapp et al., 2008; Reeves et al., 2007) particularly endometrium (Bjorge et al., 2007; McCourt et al., 2007), breasts (Dogan et al., 2007; Ahn et al., 2007) and colorectal cancers (Moghaddam et al., 2007). Adipocytes have the ability to enhance the proliferation of colon cancer cells in vitro (Amemori et al., 2007). The greatest risk is for obese persons who are also diabetic, particular those whose body mass index is above 35 kg/m2. The increase in risk is by 93-fold in women and by 42-fold in men (Jung, 1997). One of the most common cancers noted in community that has high diabetics and obesity is colorectal cancer (Othman and Zin, 2008; Yang et al., 2005; Ahmed et al., 2006; Seow et al., 2006).

In a clinical study on 55 overweight or obese patients, the control group (17 subjects) received 70 g of sucrose daily for a maximum of 30 days and patients in the experimental group (38 subjects) received 70 g of natural honey for the same period. Results showed that honey caused a mild reduction in body weight (1.3%) and body fat (1.1%) (Yaghoobi et al., 2008). Beneficial effect of honey on obesity is not well established thus far.

Honey has potential use in ‘cancer therapy’

Recent studies on human breast (Fauzi et al., 2011), cervical (Fauzi et al., 2011), oral (Ghashm et al., 2010) and osteocarcoma (Ghashm et al., 2010) cancer cell lines using Malaysian jungle Tualang honey showed significant anticancer activity. Honey has also been shown to have antineoplastic activity in an experimental bladder model in vivo and in-vitro (Swellam et al., 2003).

Honey is rich in flavonoids (Gomez-Caravaca et al., 2006; Jaganathan and Mandal, 2009). Flavanoids have created a lot of interests among researchers because of its anticancer properties. The mechanisms suggested are rather diverse such as inhibition of cell proliferation, induction of apoptosis (Ghashm et al., 2010) and cell cycle arrest (Pichichero et al., 2010) as well as inhibition of lipoprotein oxidation (Gheldof and Engeseth, 2002). It has been shown to induce early (Ghashm et al., 2010) and late apotosis (Fauzi et al., 2011) and disruption of miotochodrial membrane potential (Fauzi et al., 2011). Breast cancers developed in rats after DMBA induction show smaller tumor size and lesser number of tumors compared to controls when the rats were fed on various doses of honey (manuscript under review for publication). Honey is thought to mediate these beneficial effects due to its major components such as chrysin (Woo et al., 2004) and other flavonoids (Jaganathan et al., 2010). These differences are explainable as honeys are of various floral sources and each floral source may exhibit different active compounds. Though honey has other substances of which the most predominant are a mixture of sugars (fructose, glucose, maltose and sucrose) (Aljadi and Kamaruddin, 2004) which itself is carcinogenic (Heuson et al., 1972), it is understandable that's its beneficial effect on cancer raises skeptics. The mechanism on how honey has anti-cancer effect is an area of great interest recently. There is a lot we can learn from nature (Moutsatsou, 2007). For example, phytochemicals, such as genistein, lycopene, curcumin, epigallocatechin-gallate, and resveratrolhave been studied to be used for treatment of prostate cancer (Von Low et al., 2007). Phytoestrogens, constitute a group of plant-derived isoflavones and flavonoids and honey belongs to plant phytoestrogen (Moutsatsou, 2007; Zaid et al., 2010).

Limitations

Although the effect of honey as anti-inflammatory, anti-microbial and promotion of chronic ulcer healing is extensively studied, its effect on other causes of cancers such as smoking, obesity and alcohol is not well studied thus far. It is difficult to standardize honey. Honey from different regions may have variations in its health benefits because its efficacy depends on the floral source. Isolating the active fragment of honey does not produce as good effect as total honey.

Conclusion

There is now a sizeable evidence that honey has potential role in alleviating the causes of cancer thus a possible natural cancer vaccine. It is a natural immune booster, natural anti-inflammatory agent, natural anti-microbial agent, natural promoter for healing chronic ulcers and wounds and scavengers for toxic free radicals. Though it is essentially a sweet food and sugar is thought to be carcinogenic, its potential role in preventing cancer understandably raises skeptics. Improvement in immune status is key in prevention of cancer formation and honey has such potential. Recently it has been shown to have direct anti-cancer effect on various cancer cell lines. With increasing number of people seeking therapy from nature, this area of research has recently gained attention.

References

- 1.Ahmed R.L, Schmitz K.H, Anderson K.E, Rosamond W.D, Folsom A.R. The metabolic syndrome and risk of incident colorectal. cancer Cancer. 2006;107:28–36. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahn J, Schatzkin A, Lacey J.V, Jr, Albanes D, Ballard-Barbash R, Adams K.F, Kipnis V, Mouw T, Hollenbeck A.R, Leitzmann M.F. Adiposity adult weight change, and postmenopausal breast cancer risk. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:2091–2102. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.19.2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Jabri A.A, Al-Hosni S.A, Nzeako B.C, Al-Mahrooqi Z.H, Nsanze H. Antibacterial activity of Omani honey alone and in combination with gentamicin. Saudi Med J. 2005;26:767–771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Waili N.S. Topical application of natural honey, beeswax and olive oil mixture for atopic dermatitis or psoriasis: partially controlled, single-blinded study. Complement Ther Med. 2003;11:226–234. doi: 10.1016/s0965-2299(03)00120-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Waili N.S. An alternative treatment for pityrias is versicolor, tinea cruris, tinea corporis and tinea faciei with topical application of honey, olive oil and beeswax mixture: an open pilot study. Complement Ther Med. 2004a;12:45–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Waili N.S. Investigating the antimicrobial activity of natural honey and its effects on the pathogenic bacterial infections of surgical wounds and conjunctiva. J Med Food. 2004b;7:210–222. doi: 10.1089/1096620041224139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Waili N.S. Topical honey application vs acyclovir for the treatment of recurrent herpes simplex lesions. Med Sci Monit. 2004c;10:MT94–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Waili N.S. Clinical and mycological benefits of topical application of honey, olive oil and beeswax in diaper dermatitis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2005;11:160–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.01013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Waili N.S, Akmal M, Al-Waili F.S, Saloom K.Y, Ali A. The antimicrobial potential of honey from United Arab Emirates on some microbial isolates. Med Sci Monit. 2005;11:BR433–438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Waili N.S, Al-Waili T.N, Al-Waili A.N, Saloom K.S. Influence of natural honey on biochemical and hematological variables in AIDS: a case study. The Scientific World Journal. 2006;6:1985–1989. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2006.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Waili N.S, Haq A. Effect of honey on antibody production against thymus-dependent and thymus-independent antigens in primary and secondary immune responses. J Med Food. 2004;7:491–494. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2004.7.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alandejani T, Marsan J, Ferris W, Slinger R, Chan F. Effectiveness of honey on Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;141:114–118. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aljadi A.M, Kamaruddin M.Y. Evaluation of the phenolic contents and antioxidant capacities of two Malaysian floral honeys. Food Chemistry. 2004;85:513–518. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amemori S, Ootani A, Aoki S, Fujise T, Shimoda R, Kakimoto T, Shiraishi R, Sakata Y, Tsunada S, Iwakiri R, Fujimoto K. Adipocytes and preadipocytes promote the proliferation of colon cancer cells in vitro. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;292:G923–929. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00145.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Armstrong D.G. Manuka honey improved wound healing in patients with sloughy venous leg ulcers. Evid Based Med. 2009;14:148. doi: 10.1136/ebm.14.5.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asadi-Pooya A.A, Pnjehshahin M.R, Beheshti S. The antimycobacterial effect of honey: an in vitro study. Riv Biol. 2003;96:491–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Asuquo M, Ugare G, Ebughe G, Jibril P. Marjolin's ulcer: the importance of surgical management of chronic cutaneous ulcers. Int J Dermatol 46 Suppl. 2007;2:29–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Asuquo M.E, Udosen A.M, Ikpeme I.A, Ngim N.E, Otei O.O, Ebughe G, Bassey E.E. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in Calabar, southern Nigeria. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:870–873. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bjorge T, Engeland A, Tretli S, Weiderpass E. Body size in relation to cancer of the uterine corpus in 1 million Norwegian women. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:378–383. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bray F, Moller B. Predicting the future burden of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:63–74. doi: 10.1038/nrc1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carrillo-Infante C, Abbadessa G, Bagella L, Giordano A. Viral infections as a cause of cancer (review) Int J Oncol. 2007;30:1521–1528. doi: 10.3892/ijo.30.6.1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chou J, Lin Y.C, Kim J, You L, Xu Z, He B, Jablons D.M. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma--review of the molecular mechanisms of tumorigenesis. Head & neck. 2008;30:946–963. doi: 10.1002/hed.20833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Codoner-Franch P, Valls-Belles V, Arilla-Codoner A, Alonso-Iglesias E. Oxidant mechanisms in childhood obesity: the link between inflammation and oxidative stress. Transl Res. 2011;158:369–384. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen S.M, Purtilo D.T, Ellwein L.B. Ideas in pathology Pivotal role of increased cell proliferation in human carcinogenesis. Mod Pathol. 1991;4:371–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cooper R.A, Molan P.C, Krishnamoorthy L, Harding K.G. Manuka honey used to heal a recalcitrant surgical wound. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2001;20:758–759. doi: 10.1007/s100960100590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cutting K.F. Honey and contemporary wound care: an overview. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2007;53:49–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DCP2, 2007. Controlling Cancer in Developing Countries; prevention and treatment straategies merit further study on www.dcp2.org.

- 28.Dogan S, Hu X, Zhang Y, Maihle N.J, Grande J.P, Cleary M.P. Effects of high-fat diet and/or body weight on mammary tumor leptin and apoptosis signaling pathways in MMTV-TGF- alpha mice. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9:R91. doi: 10.1186/bcr1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.English H.K, Pack A.R, Molan P.C. The effects of manuka honey on plaque and gingivitis: a pilot study. J Int Acad Periodontol. 2004;6:63–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Estevinho L, Pereira A.P, Moreira L, Dias L.G, Pereira E. Antioxidant and antimicrobial effects of phenolic compounds extracts of Northeast Portugal honey. Food Chem Toxicol. 2008;46:3774–3779. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2008.09.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fauzi A.N, Norazmi M.N, Yaacob N.S. Tualang honey induces apoptosis and disrupts the mitochondrial membrane potential of human breast and cervical cancer cell lines. Food Chem Toxicol. 2011;49:871–878. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Franceschi S, La Vecchia C. Cancer epidemiology in the elderly. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2001;39:219–226. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(01)00102-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.French V.M, Cooper R.A, Molan P.C. The antibacterial activity of honey against coagulase-negative staphylococci. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;56:228–231. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fukuda M, Kobayashi K, Hirono Y, Miyagawa M, Ishida T, Ejiogu E.C, Sawai M, Pinkerton K.E, Takeuchi M. Jungle Honey Enhances Immune Function and Antitumor Activity. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2009 doi: 10.1093/ecam/nen086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garcia M, Jemal A, Ward E, Center M, Hao Y, Siegal R, Thun M. Global Cancer; Facts & Figures 2007. American Cancer Society. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gethin G, Cowman S. Bacteriological changes in sloughy venous leg ulcers treated with manuka honey or hydrogel: an RCT. (246-247).J Wound Care. 2008;17:241–244. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2008.17.6.29583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gethin G.T, Cowman S, Conroy R.M. The impact of Manuka honey dressings on the surface pH of chronic wounds. Int Wound J. 2008;5:185–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2007.00424.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 38.Ghashm A.A, Othman N.H, Khattak M.N, Ismail N.M, Saini R. Antiproliferative effect of Tualang honey on oral squamous cell carcinoma and osteosarcoma cell lines. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2010;10:49. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-10-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gheldof N, Engeseth N.J. Antioxidant capacity of honeys from various floral sources based on the determination of oxygen radical absorbance capacity and inhibition of in vitro lipoprotein oxidation in human serum samples. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:3050–3055. doi: 10.1021/jf0114637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gomez-Caravaca A.M, Gomez-Romero M, Arraez-Roman D, Segura-Carretero A, Fernandez-Gutierrez A. Advances in the analysis of phenolic compounds in products derived from bees. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2006;41:1220–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Henriques A.F, Jenkins R.E, Burton N.F, Cooper R.A. The intracellular effects of manuka honey on Staphylococcus aureus. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s10096-009-0817-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heppermann B. Towards evidence based emergency medicine: Best BETs from the Manchester Royal Infirmary Bet 3 Honey for the symptomatic relief of cough in children with upper respiratory tract infections. Emerg Med J. 2009;26:522–523. doi: 10.1136/emj.2009.077693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heuson J.C, Legros N, Heimann R. Influence of insulin administration on growth of the 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene- induced mammary carcinoma in intact, oophorectomized, and hypophysectomized rats. Cancer Res. 1972;32:233–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hon J. Using honey to heal a chronic wound in a patient with epidermolysis bullosa. Br J Nurs. 2005;14:S4–5. S8, S10 passim. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hooper S.J, Wilson M.J, Crean S.J. Exploring the link between microorganisms and oral cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Head Neck. 2009;31:1228–1239. doi: 10.1002/hed.21140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hrbacek J, Urban M, Hamsikova E, Tachezy R, Eis V, Brabec M, Heracek J. Serum antibodies against genitourinary infectious agents in prostate cancer and benign prostate hyperplasia patients: a case-control study. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:53. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huxley R. The role of lifestyle risk factors on mortality from colorectal cancer in populations of the Asia-Pacific region. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2007;8:191–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Iurlina M.O, Saiz A.I, Fritz R, Manrique G.D. Major flavonoids of Argentinean honeys. Optimisation of the extraction method and analysis of their content in relationship to the geographical source of honeys. Food Chemistry. 2009;115:1141–1149. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jaganathan S.K, Mahitosh M. Antiproliferative Effects of Honey and of Its Polyphenols: A Review. Journal of Biomedicine and Biotechnology 2009. 2009:13. doi: 10.1155/2009/830616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jaganathan S.K, Mandal M. Antiproliferative effects of honey and of its polyphenols: a review. J Biomed Biotechnol 2009. 2009 doi: 10.1155/2009/830616. 830616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jaganathan S.K, Mandal S.M, Jana S.K, Das S, Mandal M. Studies on the phenolic profiling, anti-oxidant and cytotoxic activity of Indian honey: in vitro evaluation. Nat Prod Res. 2010;24:1295–1306. doi: 10.1080/14786410903184408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jung R.T. Obesity as a disease. Br Med Bull. 1997;53:307–321. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kishore R.K, Halim A.S, Syazana M.S, Sirajudeen K.N. Tualang honey has higher phenolic content and greater radical scavenging activity compared with other honey sources. Nutr Res. 2011;31:322–325. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kuniyasu H, Kitadai Y, Mieno H, Yasui W. Helicobactor pylori infection is closely associated with telomere reduction in gastric mucosa. Oncology. 2003;65:275–282. doi: 10.1159/000074481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kuper H, Adami H-O, Trichopoulos D. Infections as a major preventable cause of human cancer. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2001;249:61–74. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2000.00742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Le Marchand L, Hankin J.H, Wilkens L.R, Pierce L.M, Franke A, Kolonel L.N, Seifried A, Custer L.J, Chang W, Lum-Jones A, Donlon T. Combined effects of well-done red meat, smoking, and rapid N-acetyltransferase 2 and CYP1A2 phenotypes in increasing colorectal cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10:1259–1266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McCourt C.K, Mutch D.G, Gibb R.K, Rader J.S, Goodfellow P.J, Trinkaus K, Powell M.A. Bod mass index: relationship to clinical, pathologic and features of microsatellite instability in endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;104:535–539. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McLaughlin-Drubin M.E, Munger K. Viruses associated with human cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1782:127–150. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Miorin P.L, Levy N.C, Junior, Custodio A.R, Bretz W.A, Marcucci M C. Antibacterial activity of honey and propolis from Apis mellifera and Tetragonisca angustula against Staphylococcus aureus. Journal of applied microbiology. 2003;95:913–920. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2003.02050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moghaddam A.A, Woodward M, Huxley R. Obesity and risk of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of 31 studies with 70,000 events. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:2533–2547. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Molan P.C. Potential of honey in the treatment of wounds and burns. American journal of clinical dermatology. 2001a;2:13–19. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200102010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Molan P.C. The potential of honey to promote oral wellness. General dentistry. 2001b;49:584–589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Moutsatsou P. The spectrum of phytoestrogens in nature: our knowledge is expanding. Hormones (Athens) 2007;6:173–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Oddo L.P, Heard T.A, Rodriguez-Malaver A, Perez R.A, Fernandez-Muino M, Sancho M.T, Sesta G, Lusco L, Vit P. Composition and antioxidant activity of Trigona carbonaria honey from Australia. Journal of medicinal food. 2008;11:789–794. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2007.0724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Othman N.H, Zin A.A. Association of colorectal carcinoma with metabolic diseases; experience with 138 cases from Kelantan Malaysia Asian Pac. J Cancer Prev. 2008;9:747–751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Parkin D.M, Almonte M, Bruni L, Clifford G, Curado M.P, Pineros M. Burden and trends of type-specific human papillomavirus infections and related diseases in the latin america and Caribbean region. Vaccine. 2008;26(Suppl 11):L1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Perez R.A, Iglesias M.T, Pueyo E, Gonzalez M, de Lorenzo C. Amino acid composition and antioxidant capacity of Spanish honeys. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry. 2007;55:360–365. doi: 10.1021/jf062055b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pichichero E, Cicconi R, Mattei M, Muzi M.G, Canini A. Acacia honey and chrysin reduce proliferation of melanoma cells through alterations in cell cycle progression. Int J Oncol. 2010;37:973–981. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pischon T, Nothlings U, Boeing H. Obesity and cancer. The Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2008;67:128–145. doi: 10.1017/S0029665108006976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pyrzynska K, Biesaga M. Analysis of phenolic acids and flavonoids in honey. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry. 2009;28:893–902. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rapp K, Klenk J, Ulmer H, Concin H, Diem G, Oberaigner W, Schroeder J. Weight change and cancer risk in a cohort of more than 65,000 adults in Austria. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:641–648. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Reeves G.K, Pirie K, Beral V, Green J, Spencer E, Bull D. Cancer incidence and mortality in relation to body mass index in the Million Women Study: cohort study. Bmj. 2007;335:1134. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39367.495995.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Seow A, Yuan J.M, Koh W.P, Lee H.P, Yu M.C. Diabetes mellitus and risk of colorectal cancer in the Singapore Chinese Health Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:135–138. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sharma V, Chauhan V.S, Nath G, Kumar A, Shukla V.K. Role of bile bacteria in gallbladder carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54:1622–1625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sharp A. Beneficial effects of honey dressings in wound management. Nurs Stand. 2009;24:66–68. doi: 10.7748/ns2009.10.24.7.66.c7331. 70, 72 passim. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Siddique K, Bhandari S, Harinath G. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) positive anal B cell lymphoma: a case report and review of literature. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2010;92:W7–9. doi: 10.1308/147870810X12659688851636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Swellam T, Miyanaga N, Onozawa M, Hattori K, Kawai K, Shimazui T, Akaza H. Antineoplastic activity of honey in an experimental bladder cancer implantation model: in vivo and in vitro studies. Int J Urol. 2003;10:213–219. doi: 10.1046/j.0919-8172.2003.00602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tonks A.J, Cooper R.A, Jones K.P, Blair S, Parton J, Tonks A. Honey stimulates inflammatory cytokine production from monocytes. Cytokine. 2003;21:242–247. doi: 10.1016/s1043-4666(03)00092-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tonks A.J, Dudley E, Porter N.G, Parton J, Brazier J, Smith E.L, Tonks A. A 5.8-kDa component of manuka honey stimulates immune cells via TLR4. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2007;82:1147–1155. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1106683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Valko M, Leibfritz D, Moncol J, Cronin M.T.D, Mazur M, Telser J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 2007;39:44–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Von Low E.C, Perabo F.G, Siener R, Muller S.C. Review Facts and fiction of phytotherapy for prostate cancer: a critical assessment of preclinical and clinical data. In Vivo. 2007;21:189–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Woo K.J, Jeong Y.J, Park J.W, Kwon T.K. Chrysin- induced apoptosis is mediated through caspase activation and Akt inactivation in U937 leukemia cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;325:1215–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.09.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yaghoobi N, Al-Waili N, Ghayour-Mobarhan M, Parizadeh S.M, Abasalti Z, Yaghoobi Z, Yaghoobi F, Esmaeili H, Kazemi-Bajestani S.M, Aghasizadeh R, Saloom K.Y, Ferns G.A. Natural honey and cardiovascular risk factors; effects on blood glucose, cholesterol, triacylglycerole, CRP and body weight compared with sucrose. Scientific World Journal. 2008;8:463–469. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2008.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yang Y.X, Hennessy S, Lewis J.D. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and the risk of colorectal cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:587–594. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00152-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yao L, Datta N, Tomás-Barberán F.A, Ferreres F, Martos I, Singanusong R. Flavonoids phenolic acids and abscisic acid in Australian and New Zealand Leptospermum honeys. Food Chemistry. 2003;81:159–168. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yuen M.F, Hou J.L, Chutaputti A. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the Asia pacific region. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:346–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zaid S.S, Sulaiman S.A, Sirajudeen K.N, Othman N.H. The effects of Tualang honey on female reproductive organs, tibia bone and hormonal profile in ovariectomised rats--animal model for menopause. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2010;10:82. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-10-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]