Abstract

Mucuna pruriens (Fabaceae) is an established herbal drug used for the management of male infertility, nervous disorders, and also as an aphrodisiac. It has been shown that its seeds are potentially of substantial medicinal importance. The ancient Indian medical system, Ayurveda, traditionally used M. pruriens, even to treat such things as Parkinson's disease. M. pruriens has been shown to have anti-parkinson and neuroprotective effects, which may be related to its anti-oxidant activity. In addition, anti-oxidant activity of M. pruriens has been also demonstrated in vitro by its ability to scavenge DPPH radicals and reactive oxygen species. In this review the medicinal properties of M. pruriens are summarized, taking in consideration the studies that have used the seeds extracts and the leaves extracts.

Keywords: Mucuna pruriens, Phytochemicals, Antioxidant, Parkinson's disease, Skin, Diabetes

Introduction

The genus Mucuna, belonging to the Fabaceae family, sub family Papilionaceae, includes approximately 150 species of annual and perennial legumes. Among the various under-utilized wild legumes, the velvet bean Mucuna pruriens is widespread in tropical and sub-tropical regions of the world. It is considered a viable source of dietary proteins (Janardhanan et al., 2003; Pugalenthi et al., 2005) due to its high protein concentration (23–35%) in addition its digestibility, which is comparable to that of other pulses such as soybean, rice bean, and lima bean (Gurumoorthi et al., 2003). It is therefore regarded a good source of food.

The dozen or so cultivated Mucuna spp. found in the tropics probably result from fragmentation deriving from the Asian cultigen, and there are numerous crosses and hybrids (Bailey and Bailey, 1976). The main differences among cultivated species are in the characteristics of the pubescence on the pod, the seed color, and the number of days to harvest of the pod. “Cowitch” and “cowhage” are the common English names of Mucuna types with abundant, long stinging hairs on the pod. Human contact results in an intensely itchy dermatitis, caused by mucunain (Infante et al., 1990). The nonstinging types, known as “velvet bean” have appressed, silky hairs.

The plant M. pruriens, widely known as “velvet bean,” is a vigorous annual climbing legume originally from southern China and eastern India, where it was at one time widely cultivated as a green vegetable crop (Duke, 1981). It is one of the most popular green crops currently known in the tropics; velvet beans have great potential as both food and feed as suggested by experiences worldwide. The velvet bean has been traditionally used as a food source by certain ethnic groups in a number of countries. It is cultivated in Asia, America, Africa, and the Pacific Islands, where its pods are used as a vegetable for human consumption, and its young leaves are used as animal fodder.

The plant has long, slender branches; alternate, lanceolate leaves; and white flowers with a bluish-purple, butterfly-shaped corolla. The pods or legumes are hairy, thick, and leathery; averaging 4 inches long; are shaped like violin sound holes; and contain four to six seeds. They are of a rich dark brown color, and thickly covered with stiff hairs. In India, the mature seeds of Mucuna bean are traditionally consumed by a South Indian hill tribe, the Kanikkars, after repeated boiling to remove anti-nutritional factors. Most Mucuna spp. exhibit reasonable tolerance to a number of abiotic stresses, including drought, low soil fertility, and high soil acidity, although they are sensitive to frost and grow poorly in cold, wet soils (Duke, 1981). The genus thrives best under warm, moist conditions, below 1500 m above sea level, and in areas with plentiful rainfall. Like most legumes, the velvet bean has the potential to fix atmospheric nitrogen via a symbiotic relationship with soil microorganisms.

Mucuna spp. have been reported to contain the toxic compounds L-dopa and hallucinogenic tryptamines, and anti-nutritional factors such as phenols and tannins (Awang et al., 1997). Due to the high concentrations of L-dopa (4–7%), velvet bean is a commercial source of this substance, used in the treatment of Parkinson's disease. The toxicity of unprocessed velvet bean may explain why the plant exhibits low susceptibility to insect pests (Duke, 1981). Velvet bean is well known for its nematicidic effects; it also reportedly possesses notable allelopathic activity, which may function to suppress competing plants (Gliessman et al., 1981).

Despite its toxic properties, various species of Mucuna are grown as a minor food crop. Raw velvet bean seeds contain approximately 27% protein and are rich in minerals (Duke, 1981). During the 18th and 19th centuries, Mucuna was grown widely as a green vegetable in the foothills and lower hills of the eastern Himalayas and in Mauritius. Both the green pods and the mature beans were boiled and eaten. In Guatemala and Mexico, M. pruriens has for at least several decades been roasted and ground to make a coffee substitute; the seeds are widely known in the region as “Nescafé,” in recognition of this use.

Mucuna pruriens as a traditional medicine

M. pruriens is a popular Indian medicinal plant, which has long been used in traditional Ayurvedic Indian medicine, for diseases including parkinsonism (Sathiyanarayanan et al., 2007). This plant is widely used in Ayurveda, which is an ancient traditional medical science that has been practiced in India since the Vedic times (1500–1000 BC). M. pruriens is reported to contain L-dopa as one of its constituents (Chaudhri, 1996). The beans have also been employed as a powerful aphrodisiac in Ayurveda (Amin, 1996) and have been used to treat nervous disorders and arthritis (Jeyaweera, 1981). The bean, if applied as a paste on scorpion stings, is thought to absorb the poison (Jeyaweera, 1981).

The non-protein amino acid-derived L-dopa (3,4-dihydroxy phenylalanine) found in this under-utilized legume seed resists attack from insects, and thus controls biological infestation during storage. According to D’Mello (1995), all anti-nutritional compounds confer insect and disease resistance to plants. Further, L-dopa has been extracted from the seeds to provide commercial drugs for the treatment of Parkinson's disease. L-Dopa is a potent neurotransmitter precursor that is believed, in part, to be responsible for the toxicity of the Mucuna seeds (Lorenzetti et al., 1998). Anti-epileptic and anti-neoplastic activity of methanol extract of M. pruriens has been reported (Gupta et al., 1997). A methanol extract of MP seeds has demonstrated significant in vitro anti-oxidant activity, and there are also indications that methanol extracts of M. pruriens may be a potential source of natural anti-oxidants and anti-microbial agents (Rajeshwar et al., 2005).

All parts of M. pruriens possess valuable medicinal properties and it has been investigated in various contexts, including for its anti-diabetic, aphrodisiac, anti-neoplastic, anti-epileptic, and anti-microbial activities (Sathiyanarayanan et al., 2007). Its anti-venom activities have been investigated by Guerranti et al. (2002) and its anti-helminthic activity has been demonstrated by Jalalpure (2007). M. pruriens has also been shown to be neuroprotective (Misra and Wagner, 2007), and has demonstrated analgesic and anti-inflammatory activity (Hishika et al., 1981).

Functional components of Mucuna pruriens

In addition to the low levels of sulfur-containing amino acids in M. pruriens seeds, the presence of anti-physiological and toxic factors may contribute to a decrease in their overall nutritional quality. These factors include polyphenols, trypsin inhibitors, phytate, cyanogenic glycosides, oligosaccharides, saponins, lectins, and alkaloids. Polyphenols (or tannins) are able to bind to proteins, thus lowering their digestibility. Phenolic compounds inhibit the activity of digestive as well as hydrolytic enzymes such as amylase, trypsin, chymotrypsin, and lipase. Recently, phenolics have been suggested to exhibit health related functional properties such as anti-carcinogenic, anti-viral, anti-microbial, anti-inflammatory, hypotensive, and anti-oxidant activities.

Trypsin inhibitors belong to the group of proteinase inhibitors that include polypeptides or proteins that inhibit trypsin activity. Tannins exhibit weak interactions with trypsin, and thus also inhibit trypsin activity. Phytic acid [myoinositol-1,2,3,4,5,6-hexa(dihydrogen phosphate)] is a major component of all plant seeds, which can reduce the bioavailability of certain minerals such as zinc, calcium, magnesium, iron, and phosphorus, as well as trace minerals, via the formation of insoluble complexes at intestinal pH. Phytate-protein complexes may also result in the reduced solubility of proteins, which can affect the functional properties of proteins.

Cyanogenic glycosides are plant toxins that upon hydrolysis, liberate hydrogen cyanide. The toxic effects of the free cyanide are well documented and affect a wide spectrum of organisms since their mode of action is inhibition of the cytochromes of the electron transport system (Laurena et al., 1994). Hydrogen cyanide (HCN) is known to cause both acute and chronic toxicity, but the HCN content of M. pruriens seeds is far below the lethal level. Janardhan et al. (2003) have investigated the concentration of oligosaccharides in M. pruriens seeds, and verbascose is reportedly the principal oligosaccharide therein (Siddhuraju et al., 2000). Fatty acid profiles reveal that lipids are a good source of the nutritionally essential linoleic and oleic acids. Linoleic acid is evidently the predominant fatty acid, followed by palmitic, oleic, and linolenic acids (Mohan and Janardhanan, 1995; Siddhuraju et al., 1996). The nutritional value of linoleic acid is due to its metabolism at tissue levels that produce the hormone-like prostaglandins. The activity of these prostaglandins includes lowering of blood pressure and constriction of smooth muscle. Phytohemagglutinins (lectins) are substances possessing the ability to agglutinate human erythrocytes.

The major phenolic constituent of M. pruriens beans was found to be L-dopa (5%), along with minor amounts of methylated and non-methylated tetrahydroisoquinolines (0.25%) (Sidhuraju et al., 2001; Misra and Wagner, 2004). However, in addition to L-dopa, 5-indole compounds, two of which were identified as tryptamine and 5-hydroxytryptamine, were also reported in M. pruriens seed extracts (Tripathi and Updhyay, 2001). Mucunine, mucunadine, prurienine, and prurieninine are four alkaloids that have been isolated from such extracts (Mehta and Majumdar, 1994). The chemical structures of some of these compounds are shown in Figure 1.

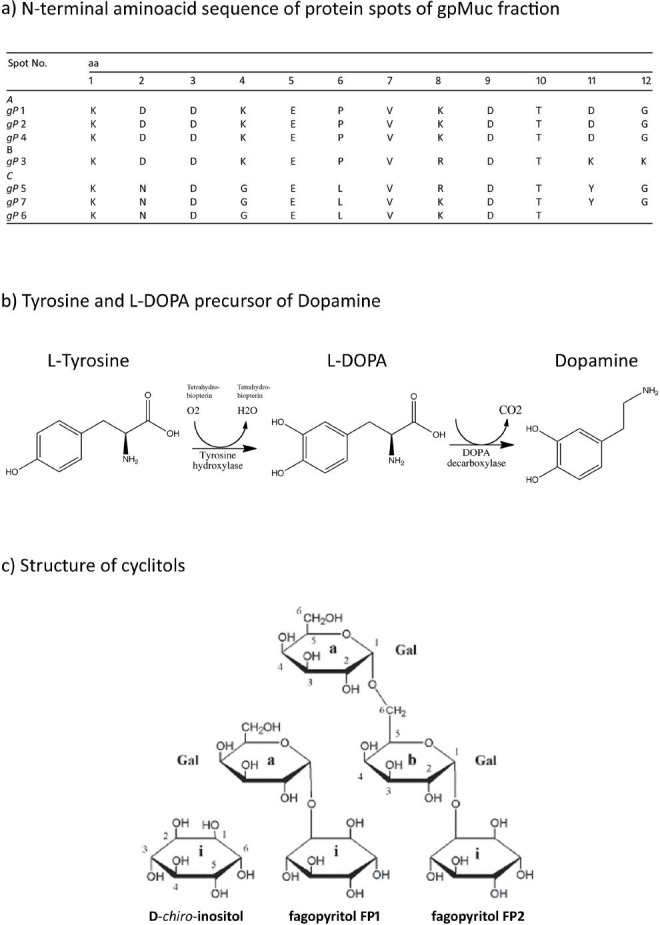

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of some proteic and non-proteic compounds contained in Mucuna pruriens

a) N-terminal amino acid sequences of proteins at positions (A) 1, 2, and 4 after gel separation, which are identical, and (B) at position 3, which is identical to those in A with regard to the first 10 aa, and (C) positions 5, 6 and 7, which differ from A in only in 3 aa.

b) The reaction representing the two steps involved in the formation of dopamine from l-tyrosine and the non-protein amino acid L-dopa (the main phenolic compound contained in MP)

c) Chemical structures of d-chiro-inositol and its two galacto-derivatives, O-α-d-galactopyranosil-(1→2)-d-chiro-inositol (FP1) and O-α-dgalactopyranosil-(1→6)-O-α-d-galactopyranosil-(1→2)-d-chiro-inositol (FP2), present in MP seeds.

Pharmacological effects of Mucuna pruriens extracts

All parts of the Mucuna plant possess medicinal properties (Sathiyanarayanan and Arulmozhi, 2007). In vitro and in vivo studies on M. pruriens extracts have revealed the presence of substances that exhibit a wide variety of pharmacological effects, including anti-diabetic, anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective and anti-oxidant properties, probably due to the presence of L-dopa, a precursor of the neurotransmitter dopamine (Misra and Wagner, 2007). It is known that the main phenolic compound of Mucuna seeds is L-dopa (approximately 5%) (Vadivel and Pugalenthi, 2008). Nowadays, Mucuna is widely studied because L-dopa is a substance used as a first-line treatment for Parkinson's disease. Some studies indicate that L-dopa derived from M. pruriens has many advantages over synthetic L-dopa when administered to Parkinson's patients, as synthetic L-dopa can have several side effects when used for many years.

In small amounts (approximately 0.25%) L-dopa corresponds to methylated and non-methylated tetrahydroisoquinoline (Siddhuraju and Becker, 2001; Misra and Wagner, 2004). These substances are present in the Mucuna roots, stems, leaves, and seeds. Other substances are present in different parts of the plant, among which are N,N-dimethyl tryptamine and some indole compounds (Tripathi and Updhyay, 2001). Alcoholic extracts of the seeds were shown to have potential anti-oxidant activity in in vivo models of lipid peroxidation induced by stress (Tripathi and Updhyay, 2001). On the other hand, Spencer et al. (1996) have reported that the pro-oxidant and anti-oxidant actions of L-dopa and its metabolites promote oxidative DNA damage and could also be harmful to tissues damaged by neurodegenerative diseases, namely parkinsonism. Moreover, a study using in vitro models revealed that L-dopa significantly increases the levels of oxidized glutathione in rat brain striatal synaptosomes (Spina et al., 1988). The observed depletion of reduced glutathione (GSH) could be due to the generation of reactive semiquinones from L-dopa (Spencer et al, 1995).

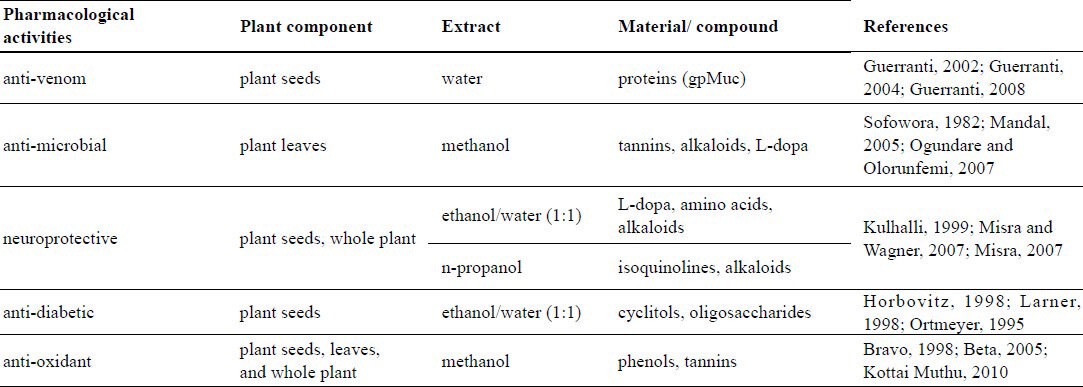

Protective effect of Mucuna pruriens seeds against snake venom poisoning

M. pruriens is one of the plants that have been shown to be active against snake venom and, indeed, its seeds are used in traditional medicine to prevent the toxic effects of snake bites, which are mainly triggered by potent toxins such as neurotoxins, cardiotoxins, cytotoxins, phospholipase A2 (PLA2), and proteases (Guerranti et al., 2002). In Plateau State, Nigeria, the seed is prescribed as a prophylactic oral anti-snakebite remedy by traditional practitioners, and it is claimed that when the seeds are swallowed intact, the individual is protected for one full year against the effects of any snake bite (Guerranti et al., 2001). The mechanisms of the protective effects exerted by M. pruriens seed aqueous extract (MPE), were investigated in detail, in a study involving the effects of Echis carinatus venom (EV) (Guerranti et al., 2002). In vivo experiments on mice showed that protection against the poison is evident at 24 hours (short-term), and 1 month (long term) after injection of MPE (Guerranti et al., 2008). MPE protects mice against the toxic effects of EV via an immune mechanism (Guerranti et al., 2002). MPE contains an immunogenic component, a multiform glycoprotein, which stimulates the production of antibodies that cross-react with (bind to) certain venom proteins (Guerranti et al., 2004). This glycoprotein, called gpMuc (see Table 1), is composed of seven different isoforms with molecular weights between 20.3 and 28.7 kDa, and pI between 4.8 and 6.5 (Di Patrizi et al., 2006).

Table 1.

Pharmacological activity of Mucuna pruriens and its compounds

It is likely that one or more gpMuc isoform is analogous in primary structure to venom PLA2. The presence of at least one shared epitope has been demonstrated with regard to MP seeds and snake venom. These cross-reactivity data explain the mechanism of the long-term protection conferred by MP, and confirm that certain plant species contain PLA2-like proteins, which are beneficial for plant growth, and are involved in important processes (Lee et al., 2005). In addition, MP seeds contain protein and non-protein components that are able to directly inhibit the activity of proteases and PLA2, and are responsible for short-term protection. In fact, MPE contains protease inhibitors that are active against snake venom, in particular a gpMuc isoform sequence also found in a “Kunitz type” trypsin inhibitor contained in soy. Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis has been used to separate the seven gpMuc isoforms, in order to perform N-terminal analysis of each individual isoform. The sequences obtained are shown in Figure 1. According to their sequences, we can group the isoforms at positions 1, 2, and 4 on the gel, which are identical in 12/12 aa. The isoform at position 3 is identical to those aforementioned, with regard to the first 10 aa, and those at positions 5, 6, and 7 differ from those at positions 1,2 and 4 by just 3 aa (Guerranti et al., 2002; Scirè et al., 2011; Hope-Onyekwere et al., 2012). On the other hand, the direct inhibitory action of MPE is probably caused by L-dopa, the main bioactive component, which acts in synergy with other compounds.

Anti-microbial properties of Mucuna pruriens leaves

Various parts of certain plants are known to contain substances that can be used for therapeutic purposes or as precursors for the production of useful drugs (Sofowora, 1982). Plant-based anti-microbials represent a vast untapped source of medicines and further investigation of plant anti-microbials is needed. Anti-microbials of plant origin have enormous therapeutic potential. Phytochemical compounds are reportedly responsible for the anti-microbial properties of certain plants (Mandal et al., 2005). While bioactive compounds are often extracted from whole plants, the concentration of such compounds within the different parts of the plant varies. Parts known to contain the highest concentration of the compounds are preferred for therapeutic purposes. Some of these active components operate individually, others in combination, to inhibit the life processes of microbes, particularly pathogens. Crude methanolic extracts of M. pruriens leaves have been shown to have mild activity against some bacteria in experimental settings (Table 1), probably due to the presence of phenols and tannins (Ogundare and Olorunfemi, 2007). Further studies are required in order to isolate the bioactive components responsible for the observed anti-microbial activity.

Neuroprotective effect of Mucuna pruriens seeds

In India, the seeds of M. pruriens have traditionally been used as a nervine tonic, and as an aphrodisiac for male virility. The pods are anthelmintic, and the seeds are anti-inflammatory. Powdered seeds possess anti-parkinsonism properties, possibly due to the presence of L-dopa (a precursor of neurotransmitter dopamine). It is well known that dopamine is a neurotransmitter. The dopamine content in brain tissue is reduced when the conversion of tyrosine to L-dopa is blocked. L-Dopa, the precursor of dopamine, can cross the blood-brain barrier and undergo conversion to dopamine, restoring neurotransmission (Kulhalli, 1999). Good yields of L-dopa can be extracted from M. pruriens seeds (Table 1) with EtOH-H2O (1:1), using ascorbic acid as a protector (Misra and Wagner, 2007). An n-propanol extract of M. pruriens seeds yields the highest response in neuroprotective testing involving the growth and survival of DA neurons in culture. Interestingly, n-propanol extracts, which contain a negligible amount of L-dopa, have shown significant neuroprotective activity, suggesting that a whole extract of M. pruriens seeds could be superior to pure L-dopa with regard to the treatment of parkinsonism.

Anti-diabetic effect of Mucuna pruriens seeds

Using a combination of chromatographic and NMR techniques, the presence of d-chiro-inositol and its two galacto-derivatives, O-α-d-galactopyranosil-(1→2)-d-chiro-inositol (FP1) and O-α-d-galactopyranosil-(1→6)-O-α-d-galactopyranosil-(1→2)-D-chiro-inositol (FP2), was demonstrated in M. pruriens seeds (Donati et al., 2005). Galactopyranosyl d-chiro-inositols are relatively rare and have been isolated recently from the seeds of certain plants; they constitute a minor component of the sucrose fraction of Glycine max (Fabaceae) and lupins, and a major component of Fagopyrum esculentum (Polygonaceae) (Horbovitz et al., 1998). Although usually ignored in phytochemical analyses conducted for dietary purposes, the presence of these cyclitols is of interest due to the insulin-mimetic effect of d-chiro-inositol, which constitutes a novel signaling system for the control of glucose metabolism (Larner et al., 1998; Ortmeyer et al., 1995). According to Anktar et al., (1990), M. pruriens seeds used at a dose of 500 mg/kg reduced plasma glucose levels. These and other data demonstrated that the amount of seeds necessary to obtain a significant anti-diabetic effect contain a total of approximately 7 mg of d-chiro-inositol (including both free, and that derived from the hydrolysis of FP1 and FP2). The anti-diabetic properties of M. pruriens seed EtOH/H2O 1:1 extract are most likely due to d-chiro-inositol and its galacto-derivatives (Table 1).

Anti-oxidant activity of Mucuna pruriens

Free radicals that have one or more unpaired electrons are produced during normal and pathological cell metabolism. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) react readily with free radicals to become radicals themselves. Anti-oxidants provide protection to living organisms from damage caused by uncontrolled production of ROS and concomitant lipid peroxidation, protein damage and DNA strand breakage. Several substances from natural sources have been shown to contain anti-oxidants and are under study. Anti-oxidant compounds such as phenolic acids, polyphenols, and flavonoids, scavenge free radicals such as peroxide, hydroperoxide or lipid peroxyl, and thus inhibit oxidative mechanisms. Polyphenols are important phytochemicals due to their free radical scavenging and in vivo biological activities (Bravo, 1998); the total polyphenolic content has been tested using Folin-Ciocalteau reagent. Flavonoids are simple phenolic compounds that have been reported to possess a wide spectrum of biochemical properties, including anti-oxidant, anti-mutagenic and anti-carcinogenic activity (Beta et al., 2005). The hydrogen donating ability of the methanol extract of M. pruriens was measured in the presence of 1,1-diphenyl-2-picryl-hydrazyl (DPPH) radical. In a recent study, Kottai Muthu et al. (2010) found that ethylacetate and methanolic extract of whole M. pruriens plant (MEMP), which contains large amounts of phenolic compounds, exhibits high anti-oxidant and free radical scavenging activities. These in vitro assays indicate that this plant extract is a significant source of natural anti-oxidant, which may be useful in preventing various oxidative stresses. It has been reported (Ujowundu et al., 2010) that methanolic extracts of M. pruriens leaves have numerous biochemical and physiological activities, and contain pharmaceutically valuable compounds (Table 1).

Possible usage of Mucuna pruriens for skin treatments

The skin is one of the main targets of several exogenous insults such as UV radiation, O3, and cigarette smoke, and all of these exert toxicity via the induction of oxidative stress (Valacchi et al., 2000). Several skin pathologies, such as psoriasis, dermatitis, and eczema, are related to increased oxidative stress and ROS production (Briganti and Picardo, 2003), and research investigating novel natural compounds with anti-oxidant proprieties is an expanding field. As mentioned above, certain plant-derived compounds have been an important source of traditional treatments for various diseases, and have received considerable attention in more recent years due to their numerous pharmacological proprieties.

Recent preliminary studies from our group have shown that human keratinocytes treated with a methanolic extract from MP leaves exhibit downregulation of total protein expression. In addition, treatment with MP significantly decreased the baseline levels of 4HNE present in human keratinocytes (Lampariello et al., 2011). This preliminary study suggests that evaluating the effect that topical MP methanolic extract treatment may have on skin diseases would be worthwhile, as would further work aimed at clarifying the mechanisms involved in such effects.

Conclusions

Mucuna pruriens is an exceptional plant. On the one hand it is a good source of food, as it is rich in crude protein, essential fatty acids, starch content, and certain essential amino acids. On the other hand, it also contains various anti-nutritional factors, such as protease inhibitors, total phenolics, oligosaccharides (raffinose, stachyose, verbascose), and some cyclitols with anti-diabetic effects. In fact, all parts of the Mucuna plant possess medicinal properties. The main phenolic compound is L-dopa (5%), and M. pruriens seeds contain some components that are able to inhibit snake venom. In addition, methanolic extracts of M. pruriens leaves have demonstrated anti-microbial and anti-oxidant activities in the presence of bioactive compounds such as phenols, polyphenols and tannins, and preliminary studies on keratinocytes support its possible topical usage to treat redox-driven skin diseases. Collectively, the studies cited in this review suggest that this plant and its extracts may be of therapeutic value with regard to several pathologies, although further work is needed to investigate in more detail the mechanisms underlying the pharmacological activities of MP.

References

- 1.Akhtar M.S, Qureshi A.Q, Iqbal J. Antidiabetic evaluation of Mucuna pruriens Linn seeds. JPMA. 1990;40:147–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amin K.M.Y, Khan M.N, Zillur-Rehman S, Khan N.A. Sexual function improving effect of Mucuna pruriens in sexually normal male rats. Fitoterapia Milano. 1996;67:53–56. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Awang D, Buckles D, Arnason J.T. Chapeco, Catarina, Brazil, Santa Catarina, Brazil: Paper presented at the International Workshop on Green Manure – Cover Crop Systems for Smallholders in Tropical and Subtropical Regions 6-12 Apr, Rural Extension and Agricultural Research Institute of Santa Catarina; 1997. The phytochemistry, toxicology and processing potential of the covercrop velvetbean (cow(h)age, cowitch) (Mucuna Adans. spp, Fabaceae) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bailey L.H, Bailey Z.E. New York, NY, USA: Macmillan; 1976. Hortus third: a concise dictionary of plants cultivated in the United States and Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beta T, Nam S, Dexter J.E, Sapirstein H.D. Phenolic content and antioxidant activity of pearled wheat and roller-milled fractions. Cereal Chem. 2005;82:390–393. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bravo L, Siddhuraju P, Saura-Calixto F. Effect of various processing methods on the in vitrostarch digestibility and resistant starch content of Indian pulses. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 1998;46:4667–4674. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Briganti S, Picardo M. Antioxidant activity, lipid peroxidation and skin diseases What's new. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:663–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2003.00751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaudhri R.D. Herbal drug industry: a practical approach to industrial pharmacognosy. 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di Patrizi L, Rosati F, Guerranti R, Pagani R, Gerwig G.J, Kamerling J.P. Structural characterization of the N-glycans of gpMuc from Mucuna pruriens seeds. 2006 doi: 10.1007/s10719-006-8715-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D’Mello J.P.F. Anti-nutritional substances in legume seeds. In: D’Mello J.P.F, Devendra C, editors. Tropical Legumes in Animal Nutrition, CAB INTERNATIONAL. Wallingford, U.K: 1995. pp. 135–172. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donati D, Lampariello L.R, Pagani R, Guerranti R, Cinci G, Marinello E. Antidiabetic oligocyclitols in seeds of Mucuna pruriens. Phytotherapy Res. 2005;19:1057–1060. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duke J.A. New York, NY, USA: Plenum press; 1981. Handbook of legumes of world economic importance. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gliessman S.R, Garcia R, Amador M. The ecological basis for the application of traditional agricultural technology in the management of tropical agro-ecosystems. Agro-Ecosystems. 1981;7:173–185. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guerranti R, Aguiyi J.C, Neri S, Leoncini R, Pagani R, Marinello E. Proteins from Mucuna pruriens and enzymes from Echis carinatus venom: characterization and cross-reactions. J Biol Chem. 277:17072–17078. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201387200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guerranti R, Aguiyi J.C, Errico E, Pagani R, Marinello E. Effects of Mucuna pruriens extract on activation of prothrombin by Echis carinatus venom. J Ethnopharmacol. 2001;75:175–180. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(00)00401-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guerranti R, Ogueli I.G, Bertocci E, Muzzi C, Aguiyi J.C, Cianti R, Armini A, Bini L, Leoncini R, Marinello E, Pagani R. Proteomic analysis of the pathophysiological process involved in the antisnake venom effect of Mucuna pruriens extract. Proteomics. 2008;8:402–412. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guerranti R, Aguiyi J.C, Ogueli I.G, Onorati G, Neri S, Rosati F, Del Buono F, Lampariello R, Leoncini R, Pagani R, Marinello E. Protection of Mucuna pruriens seeds against Echis carinatus venom is exerted through a multiform glycoprotein whose oligosaccharide chains are functional in this role. BBRC. 2004;323:484–490. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.08.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gupta M, Mazumder U.K, Chakraborti S, Bhattacharya S, Rath N, Bhawal S.R. Antiepileptic and anticancer activity of some indigenous plants. Indian J. of Physiol. Allied Sci. 1997;51:53–56. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gurumoorthi P, Pugalenthi M, Janardhanan K. Nutritional potential of five accessions of a south Indian tribal pulse Mucuna pruriens var. utilis ; II Investigation on total free phenolics, tannins, trypsin and chymotrypsin inhibitors, phytohaemagglutinins, and in vitro protein digestibility. Trop. Subtrop. Agroecosys. 2003;1:153–158. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hishika R, Shastry S, Shinde S, Guptal S.S. Preliminary phytochemical and anti-inflammatory activity of seeds of Mucuna pruriens. Indian J pharmacol. 1981;13(1):97–98. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hope-Onyekwere N.S, Ogueli G.I, Cortelazzo A, Cerutti H, Cito A, Aguiyi J.C, Guerranti R. Effects of Mucuna pruriens Protease Inhibitors on Echis carinatus. Venom Phytother Res. 2012 Mar;:23. doi: 10.1002/ptr.4663. doi: 10.1002/ptr4663 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horbovitz M, Brenac P, Obendorf R.L. Fagopyritol B1, O-α- D-galactopyranosyl-(1→2)-D-chiro-inositol, a galactosylcyclitol in maturing buckwheat seeds associated with desiccation tolerance. Planta. 1998;205:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s004250050290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Infante M.E, Perz A.M, Simao M.R, Manda F, Baquete E.F, Fernabdes A.M, Cliff G.L. Outbreak of acute toxic psychois attributed to Mucuna pruriens. The Lancet. 1990;336:1129. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92603-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jalalpure S.S, Alagawadi K.R, Mahajanashell C.S. In vitro antihelmintic property of various seed oils against Pheritima posthuma. Ind Pharm Sci. 2007;69:158–160. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Janardhanan K, Gurumoorthi P, Pugalenthi M. Nutritional potential of five accessions of a South Indian tribal pulse, Mucuna pruriens var. utilis. Part I. The effect of processing methods on the contents of L-Dopa phytic acid, and oligosaccharides. Journal of Tropical and Subtropical Agro-ecosystems. 2003;1:141–152. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jeyaweera D.M.A. Sri Lanka: National Science Council of Sri Lanka; 1981. Madicinal plants used in Ceylon Colombo. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kulhalli P. Heritage Healing. 1999 Jul;:29–30. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar D.S, Muthu* Kottai A, Smith A.A, Manavalan R. In vitro antioxidant activity of various extracts of whole plant of Mucuna pruriens (Linn) Int. J. Pharm. Tech. Res. 2010;2:2063–2070. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lampariello L.R, Cortelazzo A, Sticozzi C, Belmonte G, Guerranti R, Di Capua A, Anzini M, Valacchi G. Alba (Italy): 2012. Jun, Proeteomic profiling and post-trasductional modifications in human keratinocytes treated with Mucona Pruriens leale extract Oxygen Club of California World Congress 2012. Oxidants and Antioxidants in Biology Cell Signalling and Nutrient-Gene Interactions; pp. 20–23. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Larner J, Allan G, Kessler C, Reamer P, Gunn R, Huang L.C. Phosphoinositol glycan derived mediators and insulin resistance Prospects for diagnosis and therapy. J. Basic Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1998;9:127–137. doi: 10.1515/jbcpp.1998.9.2-4.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laurena A.C, Revilleza M.J.R, Mendoza E.M.T. Polyphenols phytate, cyanogenic glycosides and trypsin inhibitor activity of several Philippine indigenous food legumes. J. of Food Comp. and Analys. 1994;7:194–202. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee H.Y, Bahn S.C, Shin J.S, Hwang I, Back K, Doelling J.H, Ryu S.B. Multiple forms of secretory phospholipase A2 in plants. Prog. Lipid. Res. 2005;44:52–67. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lorenzetti E, Mac Isaac S, Arnason J.T, Awang D.V.C, Buckles D. The phytochemistry, toxicology and food potential of velvet bean (Mucuna adans spp. Fabaceae) In: Buckles D, Osiname O, Galiba M, Galiano G, editors. Cover crops of West Africa; contributing to sustainable agriculture. Ottawa, Canada & IITA, Ibadan, Nigeria: IDRC; 1998. p. 57. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mandal P, Sinha Babu S.P, Mandal N.V. Antimicrobial activity of saponins from Acacia auriculiformis. Fitoterapia. 2005;76:462–465. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mehta J.C, Majumdar D.N. Indian medicinal plants-V Mucuna pruriens bark (N.O; Papilionaceae) Ind J Pharm. 1994;6:92–94. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Misra L, Wagner H. Alkaloidal constituents of Mucuna pruriens seeds. Phytochemistry. 2004;65:2565–2567. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2004.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Misra L, Wagner H. Extraction of bioactive principles from Mucuna pruriens seeds. Indian J. Biochem. Biophys. 2007;44:56–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mohan V.R, Janardhanan K. Chemical analysis and nutritional assessment of lesser-known pulses of the genus. Mucuna Food Chemistry. 1995;52:275–280. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ogundare A.O, Olorunfemi O.B. Antimicrobial efficacy of the leale of Dioclea reflexa, Mucana pruriens, Ficus asperifolia and Tragia spathulata. Res. J. of Microbiol. 2007;2:392–396. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ortmeyer H.K, Larner J, Hansen B.C. Effect of D-chiroinositol added to a meal on plasma glucose and insulin in hyperinsulinemic rhesus monkeys. Obesity Research. 1995;3:605S–608S. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1995.tb00232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pugalenthi M, Vadivel V, Siddhuraju P. Alternative food/feed perspectives of an under-utilized legume Mucuna pruriens Utilis-A Review. Linn J Plant Foods Human Nutr. 2005;60:201–218. doi: 10.1007/s11130-005-8620-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rajeshwar Y, Kumar S.G.P, Gupta M, Mazumder K.U. Studies on in vitro antioxidant activities of mhetanol extract of Mucuna pruriens (Fabaceae) seeds. European Bull of Drug Research. 2005;13:31–39. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sathiyanarayanan L, Arulmozhi S. Mucuna pruriens A comprehensive review. Pharmacognosy Rev. 2007;1:157–162. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scirè A, Tanfani F, Bertoli E, Furlani E, Nadozie H.O, Cerutti H, Cortelazzo A, Bini L, Guerranti R. The belonging of gp Muc a glycoprotein from Mucuna pruriens seeds, to the Kunitz- type trypsin inhibitor family explains its direct anti-snake venom activity. Phytomedicine. 2011;18:887–895. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Siddhuraju P, Vijayakumari K, Janardhanan K. Chemical composition and protein quality of the little-known legume, velvet bean (Mucuna pruriens (L.) DC.) J. Agric. Food Chem. 1996;44:2636–2641. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Siddhuraju P, Becker K, Makkar H.P.S. Studies on the nutritional composition and antinutritional factors of three different seed material of an under-utilised tropical legume, Mucuna pruriens var. utilis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000;48:6048–6060. doi: 10.1021/jf0006630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Siddhuraju P, Becker K. Rapid reversed-phase high performance liquid chromatographic method for the quantification of L-Dopa (L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine), non-methylated and methylated tetrahydroisoquinoline compounds from Mucuna beans. Food Chem. 2001;72:389–394. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sofowora A. 1st Edn. London: John Wiley and Sons; 1982. Medicinal plants in traditional medicine in West Africa. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Spencer J.P.E, Jenner A, Butler J, Aruoma O.I, Dexter D.T, Jenner P, Halliwell B. Evaluation of the pro-oxidant and antioxidant actions of L-Dopa and dopamine in vitro: implications for Parkinson's disease. Free Rad. Res. 1996;24:95–105. doi: 10.3109/10715769609088005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spencer J.P.E, Jenner P, Halliwell B. Superoxide-dependent GSH depletion by L-Dopa and dopamine Relevance to Parkinson's disease. Neuroreport. 1995;6:1480–1484. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199507310-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spina M.B, Cohen G. Exposure of school synaptosomes to L-Dopa increases levels of oxidised glutathione. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1988;247:502–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tripathi Y.B, Updhyay A.K. Antioxidant property of Mucuna pruriens. Linn. Curr. Sci. 2001;80:1377–1378. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vadivel V, Pugalenthi M. Removal of antinutritional/toxic substances and improvement in the protein digestibility of velvet bean seeds during various processing methods. J. of Food Sci. and Technol. 2008;45:242–246. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Valacchi G, Weber S.U, Luu C, Cross C.E, Packer L. Ozone potentiates vitamin E depletion by ultraviolet radiation in the murine stratum corneum. FEBS Lett. 2000;466:165–8. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01787-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ujowundu C.O, Kalu F.N, Emejulu A.A, Okafor O.E, Nkwonta C.G, Nwosunjoku E. Afr. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2010;4:811–81. [Google Scholar]