ABSTRACT

A 12-week-old female Wire-haired miniature dachshund presented with non-progressive ataxia and hypermetria. Due to the animal’s clinical history and symptoms, cerebellar malformations were suspected. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) detected bilateral ventriculomegaly, dorsal displacement of the cerebellar tentorium, a defect in the cerebellar tentorium and a large fluid-filled cystic structure that occupied the regions where the cerebellar vermis and occipital lobes are normally located. The abovementioned cystic structure and the defect in the cerebellar tentorium were comparable to those seen in humans with Dandy-Walker syndrome. However, the presence of the cystic structure in the occipital lobe region was unique to the present case. During necropsy, the MRI findings were confirmed, but the etiology of the condition was not determined.

Keywords: canine, cerebellar malformation, MRI

A 12-week-old, female, Wire-haired miniature dachshund was referred to the Animal Medical Center of Gifu University due to a history of non-progressive ataxia and hypermetria, which had been present since the animal was 3-week-old, and the detection of apparent defects in the cerebellum during a computed tomography (CT) examination. One of the dog’s littermates displayed skeletal malformations and had a duplicated abdominal caudal vena cava, but was clinically normal.

In a neurological examination, the dog was alert and responsive; however, it was severely ataxic and exhibited head bobbing and wide head excursions to both sides. Accordingly, it repeatedly fell towards both sides and could not coordinate its movements to stand or walk; however, during brief voluntary movements, it seemed to be strong and displayed hypermetria. Cranial nerve examinations produced unremarkable results, except for the absence of the menace response, which might have been age-related rather than a neurological abnormality. A fundus examination was also unremarkable, as were the dog’s complete blood count and serum chemistry profile.

Computed tomography (Asteion Super 4®, Toshiba, Tochigi, Japan) was repeated, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (0.4-Tesla APERTO Eterna®, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) was performed to further evaluate the cerebellar lesions.

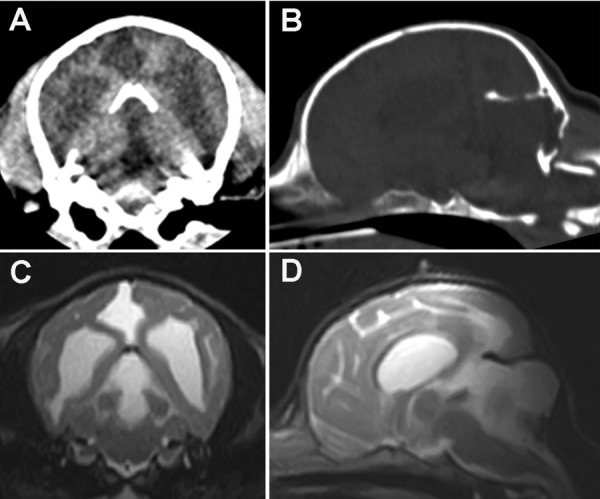

Anesthesia was induced using propofol (Mylan, Pittsburgh, PA, U.S.A.) and maintained with isoflurane (isoflurane for animals, Mylan). CT confirmed the presence of ventriculomegaly (Fig. 1A). In addition, a cystic structure was found in the region where the cerebellar vermis is normally located (Fig. 1A). A cyst was also present in the region of the occipital lobe. The rostral cerebellar tentorium had been displaced dorsally, probably due to compression by the cyst, and the middle portion of the cerebellar tentorium contained a defect (Fig. 1B). In addition, part of the left condyle of the occipital bone protruded into the caudal fossa. On T2-weighted (TR=4,500 msec and TE=100 msec) fast spin-echo images of the brain, dilated lateral and fourth ventricles were observed (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, a large cystic structure occupied the region that normally contains the vermis and extended supratentorially, displacing the occipital lobes (Fig. 1C and 1D). On fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images (TR=9,000 msec, TE=100 msec and TI=2,100 msec), the signal intensity of the periventricular areas and the regions surrounding the cyst were isointense relative to the brain parenchyma, suggesting that the pressure levels within the ventricles were not high and that the cyst had not caused edema. The cyst exhibited high signal intensity on T2-weighted images and low signal intensity on T1-weighted and FLAIR images. These findings were considered to be indicative of the accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid. We could not visualize the cerebellar vermis, but both cerebellar hemispheres were subjectively considered to be within normal limits with regard to their size and location. It was unlikely that the patient would recover; i.e., become neurologically normal; therefore, as it would have been difficult to ensure that the dog enjoyed a reasonable quality of life, it was euthanized and presented for necropsy. All of the abovementioned MRI findings were confirmed in the necropsy examination. A large fluid-filled cavity was observed in the region that normally contains the cerebellar vermis; however, the cerebellar vermis was absent (Fig. 2). The fluid in the cyst was grossly similar to cerebrospinal fluid. Furthermore, the fluid-filled cavity extended supratentorially and displaced the occipital lobes. Histologically, the rostral medullary velum on the dorsal surface of the mesencephalic aqueduct was also absent, which resulted in the mesencephalic aqueduct and subarachnoid space being connected. In addition, the ependymal cell layer lining the fourth ventricle had merged into the pia mater of each cerebellar hemisphere. A thin membranous structure, which was an extension of the arachnoid mater, formed the wall of the cyst. There were no histological abnormalities including inflammatory reactions in the rest of the cerebellum or other areas of the brain. In utero parvovirus infections have been known to cause cerebellar hypoplasia in dogs and cats [11]. Therefore, we subjected tissue samples from the cerebrum, cerebellum and brainstem to the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for parvovirus DNA. However, the results were negative for all tissues tested.

Fig. 1.

CT and MR images of the cranium and brain. A transverse CT image (A) showing bilateral ventriculomegaly and a cystic structure that occupied the region where the cerebellar vermis is normally found. The cystic structure extended into the occipital lobe. On a reformatted parasagittal CT image (B), dorsal displacement of the rostral cerebellar tentorium and a small defect in its central portion were observed. Part of the left condyle of the occipital bone protruded into the caudal fossa. On transverse and midsagittal T2-weighted MR images (C and D), the dilation of the fourth ventricle and the presence of a large cystic structure in the region that normally contains the vermis were confirmed. The cyst extended supratentorially and had displaced the occipital lobes. The MRI signal characteristics of the cystic structure were indicative of fluid accumulation.

Fig. 2.

A dorsal view of the postmortem brain specimen. Following the removal of the fluid-filled cyst, we found that the cerebellar vermis was absent. The cerebellar hemispheres were normal in size. The occipital lobes exhibited indentation caused by compression by the cyst.

In the present case, the absence of the cerebellar vermis and the cystic dilation of the fourth ventricle were comparable to the changes seen in humans with Dandy-Walker syndrome (DWS). DWS is a congenital cerebellar abnormality, which affects children and is characterized by hypoplasia or agenesis of the cerebellar vermis, cystic dilatation of the fourth ventricle and expansion of the posterior fossa [9]. In humans, other conditions, such as hydrocephalus, narrowing of the mesencephalic aqueduct, the absence of the corpus callosum, heterotopia of the cerebrum and/or cerebellum, microgyria, cerebellar meningoceles and syringomyelia, can occur concurrently with DWS [9]; however, no such abnormalities were found in the present case. The present patient fitted the profile of DWS; i.e., it had a defect that affected part of its cerebellar tentorium and a cyst that extended supratentorially. However, the continuity between the cysts in the cerebellar vermis and occipital lobe regions could not be determined definitively during necropsy, as the occipital bone was inadvertently removed which led to a rupture of the cysts.

In animals, congenital cerebellar abnormalities similar to those seen in humans with DWS have been reported in cows, horses, sheep, dogs and a cat. Among dogs, multiple breeds have been reported to suffer from such abnormalities, including Labrador retrievers, Bull terriers, Weimaraners, Dachshunds, Cocker spaniels, Boston terriers, Golden retrievers, Miniature schnauzers, Chow chows, Briards, Belgian Tervurens, Silky terriers and mixed breeds [2, 5,6,7,8, 10, 12, 13]. In these cases, the degree of cerebellar vermis malformation varied from hypoplasia to complete agenesis.

The etiology of the present patient’s cerebellar malformations was not determined. Although cerebellar hypoplasia in dogs has been linked with parvovirus infection [11], there was no evidence of infection in our case. Cerebellar abnormalities, such as those mentioned above, have been suggested to possess a heritable component in dogs [3, 7]. In our patient, since no histological evidence of neuronal degeneration or inflammation was identified, congenital defects (possibly hereditary defects) were suspected, but not confirmed. In humans, ZIC1 and ZIC4 have been identified as causative genes of DWS [4], and the deletion of ZIC1 and ZIC4 in a mouse DWS model resulted in decreased postnatal granule cell progenitor proliferation and the disruption of anterior vermis foliation [1].

The CT and MRI findings of the present case were comparable to those seen in humans with DWS. CT imaging helped us to determine the extent of the patient’s congenital defects; however, low magnetic field MRI was able to precisely depict the anatomical changes induced by the condition, which were confirmed at necropsy. In addition, the supratentorial extension of the cyst was a unique finding of the present case. There was no evidence of an in utero parvovirus infection and so congenital defects were suspected to be responsible for the dog’s condition, although its precise etiology remains unknown.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blank M. C., Grinberg I., Aryee E., Laliberte C., Chizhikov V. V., Henkelman R. M., Millen K. J.2011. Multiple developmental programs are altered by loss of Zic1 and Zic4 to cause Dandy-Walker malformation cerebellar pathogenesis. Development 138: 1207–1216. doi: 10.1242/dev.054114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choi H., Kang S., Jeong S., Cho S., Lee K., Eom K., Lee H., Chang D., Yoon J., Lee Y.2007. Imaging diagnosis-Cerebellar vermis hypoplasia in a Miniature Schnauzer. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound 48: 129–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.2007.00217.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dow R. S.1940. Partial agenesis of the cerebellum in dogs. J. Comp. Neurol. 72: 569–586. doi: 10.1002/cne.900720307 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grinberg I., Northrup H., Ardinger H., Prasad C., Dobyns W. B., Millen K. J.2004. Heterozygous deletion of the linked genes ZIC1 and ZIC4 is involved in Dandy-Walker malformation. Nat. Genet. 36: 1053–1055. doi: 10.1038/ng1420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kornegay J. N.1986. Cerebellar vermian hypoplasia in dogs. Vet. Pathol. 23: 374–379. doi: 10.1177/030098588602300405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim J. H., Kim D. Y., Yoon J. H., Kim W. H., Kweon O. K.2008. Cerebellar vermian hypoplasia in a Cocker Spaniel. J. Vet. Sci. 9: 215–217. doi: 10.4142/jvs.2008.9.2.215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noureddine C., Harder R., Olby N. J., Spaulding K., Brown T.2004. Ultrasonographic appearance of Dandy Walker-like Syndrome in a Boston Terrier. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound 45: 336–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.2004.04064.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pass D. A., Howell J. M., Thompson R. R.1981. Cerebellar malformation in two dogs and a sheep. Vet. Pathol. 18: 405–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel S., Barkovich A. J.2002. Analysis and classification of cerebellar malformations. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 23: 1074–1087 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reigner A., de Lahitte M. J. D., Delisle M. B., Dubois G. G.1993. Dandy-Walker syndrome in a kitten. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 29: 514–518 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schatzberg S. J., Haley N. J., Barr S. C., Parrish C., Steingold S., Summers B. A., deLahunta A., Kornegay J. N., Sharp N. J.2003. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of parvoviral DNA from the brains of dogs and cats with cerebellar hypoplasia. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 17: 538–544. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2003.tb02475.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmid V., Lang J., Wolf M.1992. Dandy-Walker like syndrome in four dogs: cisternography as a diagnostic aid. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 28: 355–360 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmidt M. J., Jawinski S., Wigger A., Kramer M.2008. Imaging diagnosis-Dandy Walker malformation. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound 49: 264–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.2008.00362.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]