ABSTRACT

A 10-year-old female sea otter exhibited convulsions, arrhythmia, hyperthermia, forced breathing and anorexia and died after a week. Histopathological examination revealed neoplastic proliferation of small round cells with scant cytoplasm and round or oval nuclei distributed mainly in the thalamus. The proliferation of neoplastic cells was observed in the cerebral parenchyma and perivascular areas. The neoplastic cells were immunopositive for CD3, but not CD20. No neoplastic proliferation of T-cells was found in other organs. Taken together, we diagnosed this case as a primary cerebral T-cell lymphoma. To our knowledge, this is the first case of primary cerebral T-cell lymphoma in a sea otter.

Keywords: cerebrum, lymphoma, sea otter, T-cell

Lymphomas are one of the important non-neuroectodermal tumors of the central nervous system (CNS). In most cases, CNS lymphomas are found as a part of multicentric lymphoma [15]. The primary CNS lymphomas have been reported as a rare case in dogs [2, 14], cats [4, 8, 9, 11], cow [12] and pig [7]. In humans and cats, most primary CNS lymphomas are B-cell origin [3, 11]. On the other hand, in other animals, T-cell lymphomas are the majority of primary CNS lymphomas [7]. Several tumors have been reported in sea otter (Enhydra lutris): a cholangiocellular adenocarcinoma, leiomyomas and a pheochromocytoma [13], a malignant seminoma [10] and lymphosarcoma [6]. Previously reported lymphosarcoma of sea otter was lymphoblastic, involving the mesenteric lymph node and thymus [6]. Here, we report the first case of spontaneous primary CNS T-cell lymphoma in a sea otter.

A 9-year-old female sea otter born in a zoo showed convulsions, arrhythmia, hyperthermia, forced breathing and anorexia. The sea otter was found dead a week after the first convulsion. At necropsy, no macroscopic lesion was identified in the CNS. In other organs, congestion in the liver, emphysema and congestion in the lung and mucosal hyperemia in the trachea were observed. The organs were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and sent to Laboratory of Veterinary Pathology at Osaka Prefecture University. The formalin fixed tissues were processed routinely, embedded in paraffin wax, sectioned at 4 µm in thickness and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE). In addition to HE stain, immunohistochemistry was also performed using rabbit anti-CD3 (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark, 1:500), rabbit anti-CD20 (Lab Vision, Fremont, CA, U.S.A., 1:1,000), mouse anti- proliferation cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) (clone PC10, Dako, 1:5,000), rabbit anti- glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) (Dako, 1:5,000) and rabbit anti-Iba-1 (Wako, Osaka, Japan, 1:1,000) antibodies. The sections were incubated with the primary antibodies for 60 min at room temperature. Then, the sections were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse or rabbit IgG secondary antibodies (Nichirei, Tokyo, Japan) for 60 min. Signals were visualized with 3, 3-diaminobenzidine (DAB) substrate (Nichirei). Cross reactivity of anti-CD3 and CD20 antibodies was confirmed by immunohistochemistry using the normal lymph nodes.

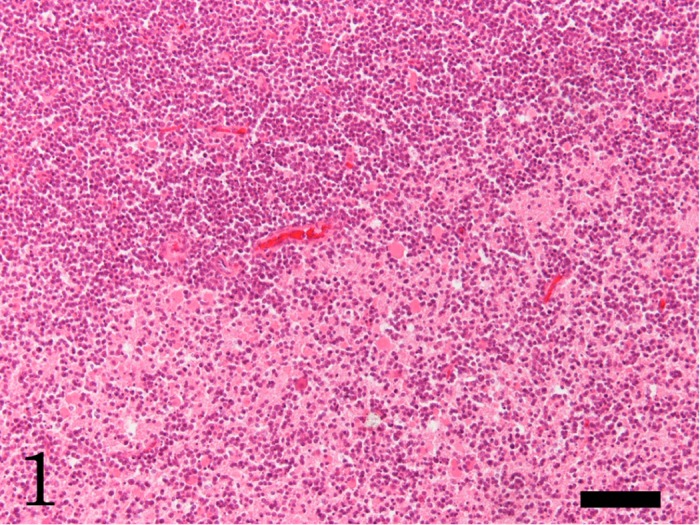

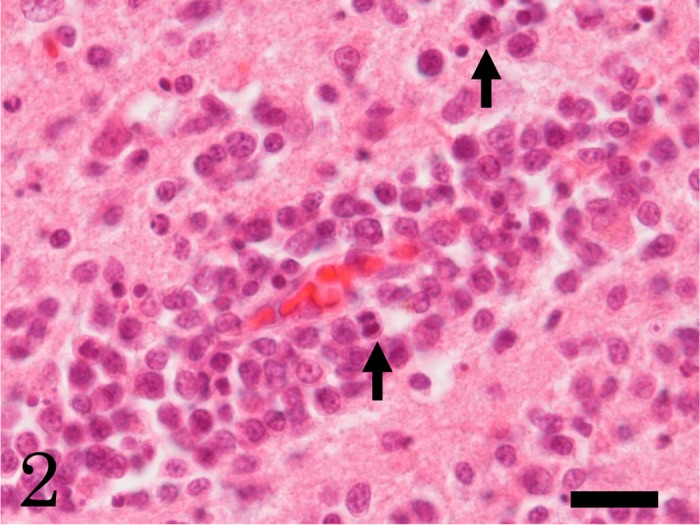

In the brain, multifocal neoplastic proliferation of small round cells was observed mainly in the thalamus and periventricular zone around the third ventricle (Figs. 1 and 2). The aggregations of neoplastic cells were bilaterally located in the cerebral parenchyma. The neoplastic cells invaded diffusely surrounding parenchyma (Fig. 1). The neoplastic cells were often found in the perivascular spaces (Fig. 2). Edema and hemorrhages were occasionally observed around the blood vessels surrounded by neoplastic cells. Necrosis with infiltration of many foamy macrophages was also observed at the lesion with severe proliferation of the round cells. A small number of neutrophils infiltrated into the neoplastic lesions. The neoplastic cells were 4–9 µm in diameter and had scant cytoplasm and round or oval nuclei with one or two nucleoli (Fig. 2). The neoplastic cells showed moderate cellular and nuclear pleomorphism. Mitotic figures were occasionally observed (Fig. 2, arrow). Apoptotic neoplastic cells were frequently observed. In other organs, adrenal cortical adenoma, granular degeneration and swelling of hepatocytes, congestion in the spleen and congestive edema and emphysema in the lung were observed; however, lymphatic system was histopathologically normal, and no neoplastic cell was observed, except for the brain.

Fig. 1.

Focal proliferation of neoplastic cells at the cerebral parenchyma. The neoplastic round cells diffusely invade the surrounding parenchyma. HE. Bar=100 µm.

Fig. 2.

High power view of the round neoplastic cells into perivascular areas in the cerebrum. The neoplastic cells show moderate cellular and nuclear pleomorphism. Arrows indicate mitotic figure. HE. Bar=20 µm.

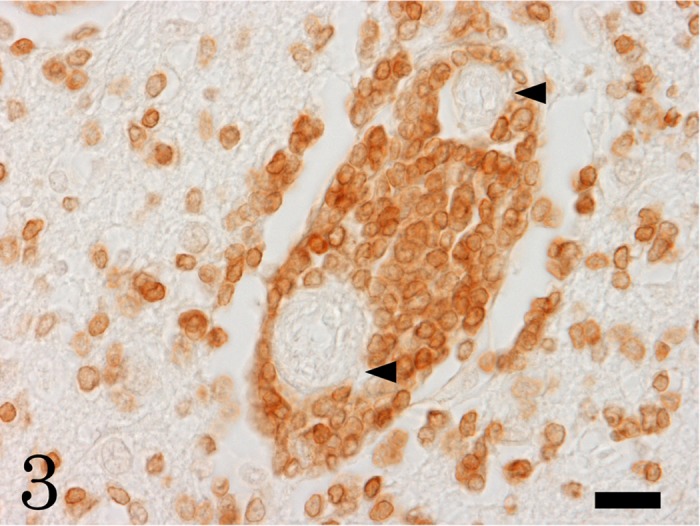

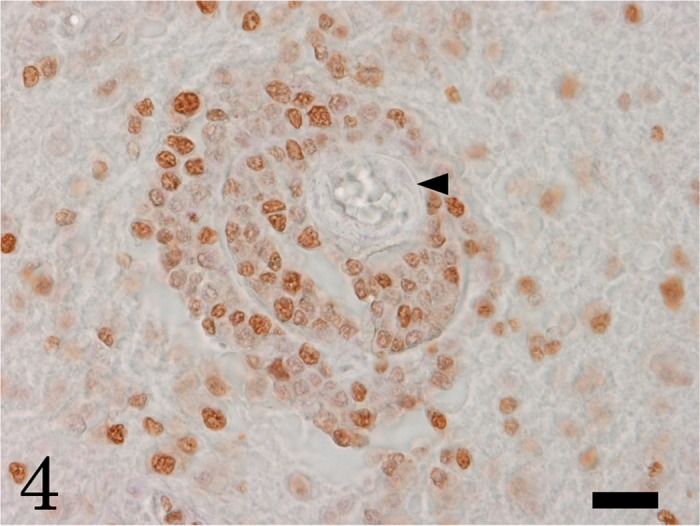

Immunohistochemically, the neoplastic round cells were positive for CD3, a T-cell marker (Fig. 3); but, negative for CD20, a B-cell marker. A large number of neoplastic cells were positive for PCNA, indicating high proliferative activity (Fig. 4). Numerous Iba-1-positive microglia and macrophages were observed in the neoplastic lesions, and increased number of GFAP-positive hypertrophic astrocytes was seen around the neoplasm. Taken together, we diagnosed this sea otter case as a primary cerebral T-cell lymphoma.

Fig. 3.

The neoplastic cells are CD3-immunopositive T-cells. Arrowheads indicate blood vessels. Bar=20 µm.

Fig. 4.

Many neoplastic cells show proliferative activity by PCNA immunohistochemistry. Arrowhead indicates blood vessel surrounded by neoplastic cells. Bar=20 µm.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of primary CNS T-cell lymphoma in the sea otter. When many lymphocytes are found in the CNS, inflammatory response should be considered as a differential diagnosis. In the present case, we diagnosed the CNS lesion as a T-cell lymphoma, because of massive proliferation of CD3-positive cells in the cerebral parenchyma with moderate cellular and nuclear pleomorphism. Perivascular orientation of the neoplastic cells is the characteristic of the CNS lymphomas in humans and animals [5, 7]. In dogs and cats, the CNS lymphoma has been found to occur at various sites, such as thalamus, hypothalamus, olfactory bulb, midbrain, pons, cerebellum, spinal cord, meninx and periventricular area [7,8,9, 11, 14]. Because of widespread distribution of CNS lymphomas, it appears to be difficult to identify the primary site in the CNS. In the present case, multifocal proliferation of neoplastic cells was seen in the thalamus and around the third ventricle; therefore, we could not identify the primary site of the lymphoma. Histopathologically, CNS lymphoma in the sea otter was similar to CNS lymphomas in other species.

In humans, primary CNS lymphomas often occur in immunosuppressed individuals like transplant recipients or human immunodeficiency virus infected patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome [5]. In cats, the pathogenesis of lymphoma is related to feline leukemia virus and feline immunodeficiency virus infections [1]. On the other hand, in sea otter, infection with the immunodeficiency viruses has not been identified. In this study, we did not examine infectious agents virologically; the detailed pathogenesis of primary CNS lymphoma in sea otter remains to be clarified.

REFERENCES

- 1.Callanan J. J., Jones B. A., Irvine J., Willett B. J., McCandlish I. A., Jarrett O.1996. Histologic classification and immunophenotype of lymphosarcomas in cats with naturally and experimentally acquired feline immunodeficiency virus infection. Vet. Pathol. 33: 264–272. doi: 10.1177/030098589603300302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Couto C. G., Cullen J., Pedroia V., Turrel J. M.1984. Central nervous system lymphosarcoma in the dog. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 184: 809–813 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferracini R., Pileri S., Bergmann M., Sabattini E., Rigobello L., Gambacorta M., Galli C., Manetto V., Frank G., Godano U., Spagnolli F., Casadei G., Azzolini U., Falini B., Gullotta F.1993. Non-Hodgkin lymphomas of the central nervous system. Clinico-pathologic and immunohistochemical study of 147 cases. Pathol. Res. Pract. 189: 249–260. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(11)80507-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fondevila D., Vilafranca M., Pumarola M.1998. Primary central nervous system T-cell lymphoma in a cat. Vet. Pathol. 35: 550–553. doi: 10.1177/030098589803500613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frosch M. P.2007. The nervous system. p. 885. In: Robbins Basic Pathology, 8th ed. (Kumar, V., Abbas, A. K., Faust, N. and Mitchell, R. N. eds.), Saunders, Philadelphia. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim J. H., Kim B. H., Kim J. H., Yoo M. J., Kim D. Y.2002. Lymphosarcoma in a sea otter (Enhydra lutris). J. Wildl. Dis. 38: 616–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koestner A., Higgins R. J.2002. Tumors of the nervous system. pp. 724–725. In: Tumors in Domestic Animals, 4th ed. (Meuten, D. J. ed.), Iowa State Press, Ames. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lane S. B., Kornegay J. N., Duncan J. R., Oliver J. E., Jr1994. Feline spinal lymphosarcoma: a retrospective evaluation of 23 cats. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 8: 99–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.1994.tb03205.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morita T., Kondo H., Okamoto M., Park C. H., Sawashima Y., Shimada A.2009. Periventricular spread of primary central nervous system T-cell lymphoma in a cat. J. Comp. Pathol. 140: 54–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2008.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reimer D. C., Lipscomb T. P.1998. Malignant seminoma with metastasis and herpesvirus infection in a free-living sea otter (Enhydra lutris). J. Zoo. Wildl. Med. 29: 35–39 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sant’Ana F. J. F., de Reis Junior J. L., Brown C. C., Langohr I. M., Barros C. S. L.2010. Primary brain T-cell lymphoma in a cat. Braz. J. Vet. Pathol. 3: 56–59 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith B. P., Anderson M.1977. Lymphosarcoma of the brain in a heifer. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 170: 333 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stetzer E., Williams T. D., Nightingale J. W.1981. Cholangiocellular adenocarcinoma, leiomyomas and pheochromocytoma in a sea otter. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 179: 1283–1284 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Umemura T., Kawaminami A., Goryo M., Itakura C.1987. Primary lymphosarcoma of the brain in a dog. Jpn. J. Vet. Sci. 49: 169–171. doi: 10.1292/jvms1939.49.169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zaki F. A., Hurvitz A. I.1976. Spontaneous neoplasms of the central nervous system of the cat. J. Small Anim. Pract. 17: 773–782. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.1976.tb06943.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]