Abstract

Two young women, were reffered to our hospital on two different occasions with history of breathlessness and mental confusion, following consumption of two different bio-organic plant nutrient compounds with a suicidal intent. On examination, they had cyanotic mucous membranes, and their blood samples showed the classic ‘dark chocolate brown’ appearance. Work up revealed cyanosis unresponsive to oxygen supplementation and absence of cardiopulmonary abnormality. Pulse oximetry revealed saturation of 75% in case 1 and 80% in case 2, on 8 liters oxygen supplementation via face masks, although their arterial blood gas analysis was normal, suggestive of “saturation gap”. Methemoglobinemia was suspected based on these findings and was confirmed by Carbon monoxide-oximetry (CO-oximetry). Methylene blue was administered and the patients showed dramatic improvement. Both the patients developed evidence of hemolysis approximately 72 hours following admission which improved with blood transfusion and supportive treatment. The patients were eventually discharged without any neurological sequalae.

Keywords: Bio-organic compound, haemolytic anemia, methemoglobinemia, methylene blue, saturation gap

Introduction

Methemoglobinemia is one of the rare causes of cyanosis in clinical practice, and exposure to oxidizing chemicals is the most common cause. Acquired methemoglobinemia may present as a serious medical emergency. The diagnosis is mainly clinical and because of its potential lethal nature, a very high degree of clinical suspicion is important. Herein we present two cases of bio-organic plant nutrient compound poisoning with unexplained cyanosis and hemolysis, which ultimately led to the diagnosis of methemoglobinemia on physical findings and blood gas analysis.

Case Reports

A 27-years-old lady presented to our emergency room with complaints of breathlessness and altered sensorium. She had clinical history of alleged consumption of 250ml of bio-organic plant nutrient (growth enhancer) containing 4% of nitrogen-based compound (CORONA), with suicidal intent, 4 hours before arrival to our hospital. She had no notable history of any systemic illness. On examination her mucous membranes were cyanotic. Vital signs at presentation were as follows: Pulse rate, 90 beats/min; respiratory rate, 28 breaths/min; and blood pressure, 100/60 mmHg. Bilateral breath sounds were clear on auscultation and heart sounds were normal. Her arterial blood samples appeared chocolate brown which failed to change colour on exposure to air [Figures 1 and 2]. On 8L/min of supplemental oxygen via face mask, pulse oximetry showed a saturation of 75%, and arterial blood gas analysis showed a partial pressure of O2 of 121 mmHg (80 to 105 mmHg) and a hemoglobin O2 saturation level of 97.8%. Electrocardiogram and chest radiograph were within normal limits.

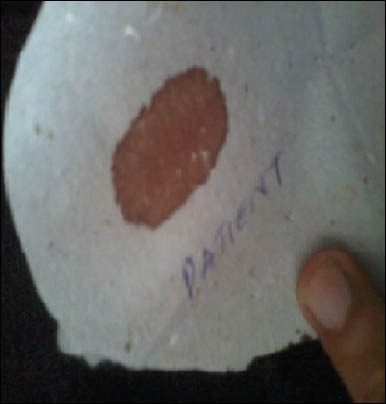

Figure 1.

Filter paper test in the patient: Blood sample with high methemoglobin fractions placed on a filter paper fails to change colour on exposure to air

Figure 2.

Filter paper test in control: Colour of blood changes to bright red on exposure to air

Our second patient, a 28-years-old lady, presented to our hospital on a different occasion with similar complaints as the other patient, as described above. She had clinical history of alleged consumption of a similar bio-organic plant nutrient compound named NAXODUS. (the content details of which were not available for our reference) approximately 6 hours before presentation, with an intention of suicide. She also had no notable medical history. On inspection, she had generalized cyanosis. Her vital signs at presentation were as follows: Pulse rate, 90 beats/min; respiratory rate, 27 breaths/min; and blood pressure, 100/60 mmHg. Her chest was clear on auscultation. She had no evidence of organophosphorous compound clinically, which is not very uncommon at our center. Her blood samples were also of the classic chocolate-brown color. On 8 L/min of supplemental oxygen, pulse oximetry showed an oxygen saturation of 80%, and arterial blood gas analysis showed a partial pressure of O2 of 125 mmHg (80 to 105 mmHg) and a hemoglobin O2 saturation level of 100%. Electrocardiography and chest radiography were within normal limits.

Both patients were treated initially with gastric lavage and activated charcoal in the emergency room, and both received oxygen supplementation via face masks. However, no significant improvement was noted and hence they were admitted to the ICU and mechanically ventilated. All laboratory investigations including hemogram, renal function tests, liver function tests and plasma pseudocholineesterase levels were normal. So here were two cases with cyanosis in the presence of normal oxygen tension. The classical dark chocholate colour of arterial blood and the disparity between the pulse oximeter readings and calculated oxygen saturations evoked the suspicion of methemoglobinemia. Antidotal therapy with 100mg methylene blue was administered intravenously over 5 minutes. The clinical conditions of both patients improved dramatically within 30 minutes, along with a gradual resolution of the cyanosis and mental confusion. Pulse oximetry readings improved to 92% in the first patient and 95% in the second and both of them were extubated within the next 48 hours. The methemoglobin concentration by carbon monoxide (CO)-oximeter were 14% and 16%, respectively. Both patients reported of fatigue, giddiness approximately 72 hours following admission. Examination revealed tachycardia, markedly pale mucous membranes and icterus. Hemogram revealed a marked drop in hemoglobin values (reduced to 5 gm% from a initial value of 12 gm% in case 1 and 4 gm% from 11 gm% in case 2), high reticulocyte count (14% and 12%, respectively) and the peripheral smear revealed marked anisocytosis and fragmented red blood cells. Liver function tests revealed indirect hyperbilirubinemia, with liver enzymes being normal. Other tests such as Coombs test, abdominal ultrasonography and Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) levels were within normal limits. Further doses of methylene blue were held and packed cell transfusions given. At the end of one week, both showed significant clinical recovery with the absence of cyanosis, increased hemoglobin values, and other systems being unremarkable. Both patients were eventually discharged from the hospital with normal blood investigations and without any neurological sequalae.

Discussion

Methemoglobinemia is an altered state of hemoglobin whereby the ferrous form of iron is oxidized to the ferric state, rendering the heme moiety incapable of carrying oxygen. Acute toxic methemoglobinemia may represent a serious medical emergency because of loss of oxygen carrying capacity of blood and shift of oxygen dissociation curve to the left.[1] The symptoms of methemoglobinemia can range in severity from dizziness to coma. Patients may present with cyanosis when the methemoglobin concentration reaches levels of approximately 10% of the total hemoglobin level. The diagnostic clues for methemoglobinemia are: (a) Dark chocholate color of arterial blood which fails to change colour on exposure to air.[2] (b) Cyanosis unresponsive to 100% oxygen. (c) Oxygen saturation gap i.e., low saturation on pulse oximetry with high saturation on routine arterial blood gas analysis. The saturation gap should alert the physician and the diagnosis should be confirmed by CO-oximetry.[3] Traditional pulse oximetry is inaccurate and unreliable in patients with high methemoglobin fractions.[4] Methylene blue is indicated as the first-line antidotal therapy for patients with severe methemoglobinemia.[5] Although, successful treatment with plasma exchange therapy, hyperbaric oxygen therapy and ascorbic acid has also been reported, these therapies should be considered as second-line treatments for patients unresponsive to methylene blue. The initial dose of methylene blue is 1 to 2 mg/kg intravenously. If symptoms of hypoxia fail to subside, the same dose may be repeated within an hour.[6] As expected, the agents producing methemoglobinemia may also produce oxidant induced hemolysis and hence a combination of methemoglobinemia and hemolytic anemia may occur, as seen in our patients. Methylene blue may trigger hemolysis in patients with G6PD deficiency.[7] However, this seemed to be unlikely in our patients, given the normal measured G6PD levels. Acquired methemoglobinemia most commonly results from exposure to oxidizing chemicals such as nitrites. Both our patients had exposure to bio-organic plant nutrient compounds, one of them being a nitrogen-based compound. Though the offending agent in the other compound could not be identified, the presence of organic nitrates, nitrites and chlorates in the bio-organic compound seems to be the likely possibility.

Acknowledgment

We express our gratitude to R. L Jallappa Hospitals, Sri Devaraj Urs Medical College and Univeristy and Department of Medicine for their support.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Darling RC, Roughton FJ. The effect of methemoglobinemia on the equilibrium between oxygen and hemoglobin. Am J Physiol. 1942;137:56. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henretig FM, Gribetz B, Kearney T, Lacouture P, Lovejoy FH. Interpretation of color change in blood with varying degree of methemoglobinemia. J ClinToxicol. 1998;26:293–301. doi: 10.1080/15563658809167094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haymond S, Cariappa R, Eby CS, Scott MG. Laboratory assessment of oxygenation in methemoglobinemia. Clin Chem. 2005;51:434–44. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.035154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ralston AC, Webb RK, Runciman WB. Potential errors in pulse oximetry: Effects of interference, dyes, dyshaemoglobins and other pigments. Anaesthesia. 1991;46:291–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1991.tb11501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clifton J, 2nd, Lerkin JB. Methylene blue. Am J Ther. 2003;10:289–91. doi: 10.1097/00045391-200307000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rees SM, Nelson LS. Dyshemoglobinemias. In: Tintinalli JE, Kelen GD, Stapczynski JS, editors. Emergency Medicine-a comprehensive study guide. 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2004. pp. 1169–71. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosen PH, Johnson C, McGehee WG, Beutler E. Failure of methylene blue treatment in toxic methemoglobinemia: Association with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. Ann Intern Med. 1971;75:83–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-75-1-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]