Abstract

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is low-grade lymphoma of mature B cells and it is considered to be the most common type of hematological malignancy in the western world. CLL is characterized by a chronically relapsing course and clinical and biological heterogeneity. Many patients do not require any treatment for years. Although important progress has been made in the treatment of CLL, none of the conventional treatment options are curative. Recurrent chromosomal abnormalities have been identified and are associated with prognosis and pathogenesis of the disease. More recently, unbiased genome-wide technologies have identified multiple additional recurrent aberrations. The precise predictive value of these has not been established, but it is likely that the genetic heterogeneity observed at least partly reflects the clinical variability. The present article reviews our current knowledge of predictive markers in CLL using whole-genome technologies.

Keywords: chronic lymphocytic leukemia, genome-wide technologies, massively parallel sequencing, next-generation technology, predictive biomarker, prognostic biomarker, SNP microarray

The advent of molecular diagnostics has led to more accurate identification and classification of hematological malignancies. For example, classification and diagnosis of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) has evolved from the French–American–British classification, based on basic morphologic criteria and cytochemistry, to the WHO’s classification system that makes use of molecular characteristics [1] such as mutations in NPM1, FLT3-ITD and CEBPA to identify new risk categories in AML [2]. Significantly, the characterization of molecular pathways involved in leukemogenesis has subsequently led to the development of novel targeted therapies. Examples of how molecular knowledge has successfully translated into improved response prediction and targeted treatment include BCR–ABL, targeted by the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib in chronic myeloid leukemia [3], and the treatment of PML-RARA fusion transcript-positive AML with all-trans retinoic acid [4].

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia

The present review will focus on chronic lympho cytic leukemia (CLL). CLL is considered to be the most common type of hematological malignancy in the western world, mainly affecting elderly individuals, with a higher incidence in males [5]. CLL is a low-grade lymphoma of mature B cells and many patients do not require any treatment for years. Constitutive activation of the B-cell receptor pathway and recurrent genomic aberrations both play critical roles in the pathogenesis of the disease [6]. CLL is characterized by clinical and biologic heterogeneity. Clinical features include constitutional symptoms, lymphadenopathy and bone marrow failure. The life expectancies of patients with CLL historically ranged from months to decades from the time of diagnosis [7].

Important progress has been made in the treatment of CLL, especially with the introduction of chemoimmunotherapeutic approaches such as the combination of rituximab, fludarabine and cyclophosphamide (FCR). However, none of the available conventional treatment options are curative and approximately 25 and 50% of patients relapse within 2 years of first- [8] or second-line [9] therapy, respectively.

CLL can be subclassified into different prognostic groups by the IGHV gene mutational status and certain genetic events. Recurrent chromosomal abnormalities have been identified and are associated with prognosis and pathogenesis of the disease [10-14].

More recently, genome-wide technologies have identified additional recurrent aberrations. The predictive value of these has not been precisely established, but it is likely that the genetic heterogeneity observed at least partly reflects the clinical variability. There is emerging evidence that many different gene mutations drive CLL pathogenesis and affect subsequent overall response to therapy and survival [15,16]. Accordingly, the establishment of a universal and comprehensive predictive panel of recurrent acquired genetic abnormalities in CLL for application in clinical practice will be challenging. The present article reviews and discusses our current knowledge of predictive markers in CLL in the context of targeted and genome-wide molecular technologies.

Predictive versus prognostic biomarkers

It is important to differentiate predictive from prognostic biomarkers. Multiple prognostic markers have been described in CLL; however, only few have been validated in clinical trials and even fewer have predictive value [17]. Whereas prognostic biomarkers indicate the overall clinical course of the disease irrespective of treatment, predictive biomarkers pinpoint patients most likely to respond to a specific therapy [18,19]. Predictive biomarkers are the key to personalized medicine, ideally predicting treatment response before it is given, thereby protecting the patient from adverse effects caused by ineffective drugs. Moreover, as CLL is characterized by considerable genomic instability [16,20], treating CLL with the right treatment at the right time might prevent the emergence of clonal evolution and chemotherapy refractoriness. Unfortunately, unlike prognostic markers, CLL predictive markers are limited: minimal residual disease monitored either by PCR or immunophenotyping is currently used, primarily within clinical trials as a surrogate marker for overall survival [21,22], or to identify patients who might benefit from maintenance therapy, and after stem cell transplantation to guide the use of donor lymphocyte infusions. Deletions and/or mutations of TP53 located at chromosome 17p13.1 are widely accepted as markers of poor CLL outcome and are considered important predictive genetic markers for chemorefractoriness [8,23-34]. In the prerituximab era, interstitial deletions involving the long arm of chromosome 11 (del11q), especially when associated with an ATM mutation on the other allele [35], were another prognostic marker for adverse outcome [10,24,35]. Chemoimmunotherapy has been found to overcome the poor prognostic impact of del11q [8,36], suggesting that patients with the del11q abnormality particularly benefit from the addition of rituximab to the chemotherapy backbone.

Known recurrent chromosomal aberrations

FISH is the most frequently used approach for identifying chromosomal aberrations and is widely available in routine CLL diagnostics. FISH uses specific probes targeted to regions of interest to search for chromosomal losses or gains in CLL cells. Interphase FISH can be successfully applied to nondividing cells such as CLL cells. The classical FISH probe panel for CLL includes probes targeting 13q14, 11q22.3 and 17p13.1 deletions, as well as trisomy 12. A set of five prognostic categories were defined by Döhner et al. and were later confirmed in other studies [10]. The worst prognosis of these categories was shown in patients with del17p13.1 involving the TP53 gene, followed by del11q22.3, trisomy 12q13 and those with a normal diploid karyotype, while patients with del(13q14) as the sole chromosomal abnormality had a good prognosis [37-39]. The incidence of del17p13.1 and del11q22.3 increases with multiple treatments (5–30%) [40].

TP53 mutations

In 85% of CLL cases, del17p is associated with TP53 mutations on the other chromosomal allele; however, many studies of CLL patients have also detected mono- or bi-allelic TP53 mutations in the absence of del17p. TP53 mutations in the absence of deletion have the same adverse impact on survival, but are not revealed by FISH [13,30,32,40,41]. The identification of a TP53 mutation/deletion predicts chemotherapy resistance and directs treatment to chemotherapy-free agents such as alemtuzumab, a humanized IgG1 anti-CD52 [42]. Screening prior to each treatment initiation is now recommended by the British Society of Hematology and European Research Initiative of CLL guidelines [33].

However, even the combination of FISH and mutation analysis to detect abnormalities of TP53 will, at best, detect only 50% of patients who will relapse within 2 years after first- [8] or second- [9] line chemoimmunotherapy. Therefore, there is an urgent need to detect other potential response predictors.

Genome-wide microarrays to detect somatically acquired copy number alterations & SNPs

Copy number variants (CNVs) have been defined as DNA segments of at least 1 kb in size, but ranging to many kb, in which a comparison of two or more genomes reveals gains or losses of copy number relative to the reference genome [43,44]. Clinically, CNVs may be benign, directly pathogenic or represent risk factors for diseases. They are germline events that are considered polymorphic when present in more than 1% of the reference genome and they are generally believed to not be involved in malignancies [43,44]. By contrast, somatic copy number alterations (CNAs) are acquired alterations that often correspond to losses or gains of genetic material in cancers, including CLL. CNAs can be very small in size (0.5 kb), but more often they affect large regions and sometimes whole chromosomes [20,45].

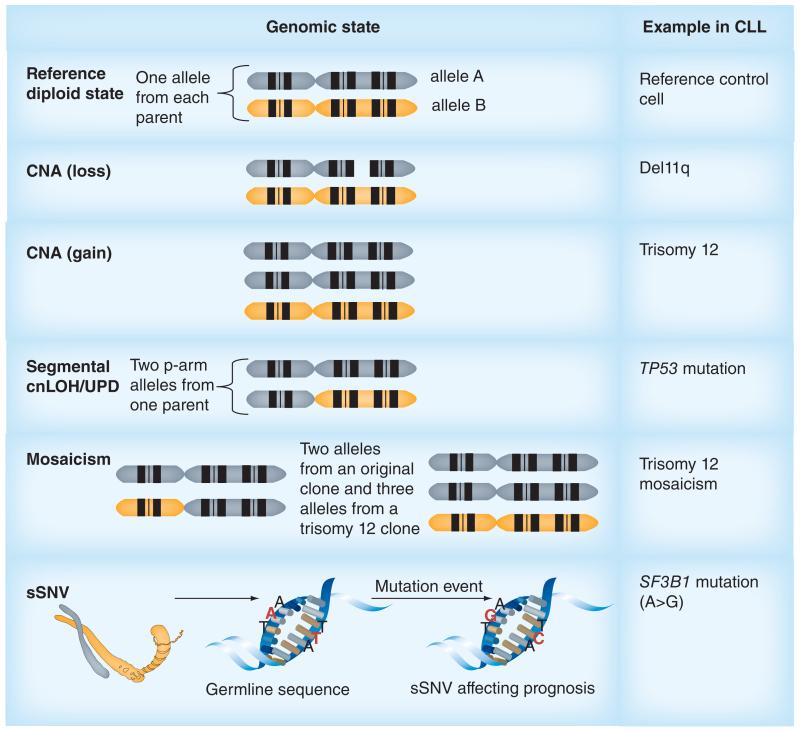

The genetic heterogeneity of CLL requires sensitive molecular techniques that can detect both CNAs and copy-neutral loss of heterozygosity (cnLOH, also referred to as acquired uniparental isodisomy [UPD]) that may occur only in a small proportion of malignant cells (Figure 1) [20,31,46-51]. Segmental UPD is caused by duplication of part of a chromosomal region from one parent and deletion of the corresponding allele from the second, leading to a diploid but isodisomic state. Constitutional UPD (i.e., present at birth and found in germline DNA) may arise due to meiotic or postfertilization errors during early mitotic division and constitutional cnLOH may, in addition, be due to consanguinity (where parents have segments of chromosome in common) [52]. In cancer, acquired whole or segmental UPD may result from errors in mitosis and during the cell cycle [53].

Figure 1. Types of genomic aberrations detected by microarrays and examples seen in chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Both comparative genomic hybridization and SNP arrays can reveal somatic CNAs. In addition, SNP arrays allow the detection of mosaicism and cnLOH. cnLOH may occur as a result of UPD. SNP arrays differ from comparative genomic hybridization arrays in that the arrayed probes are oligonucleotides designed to specifically detect SNPs and therefore sSNV involving these probes might also be detected.

CLL: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CNA: Copy number alterations; cnLOH: Copy-neutral loss of heterozygosity; sSNV: Somatic single nucleotide variation; UPD: Uniparental disomy.

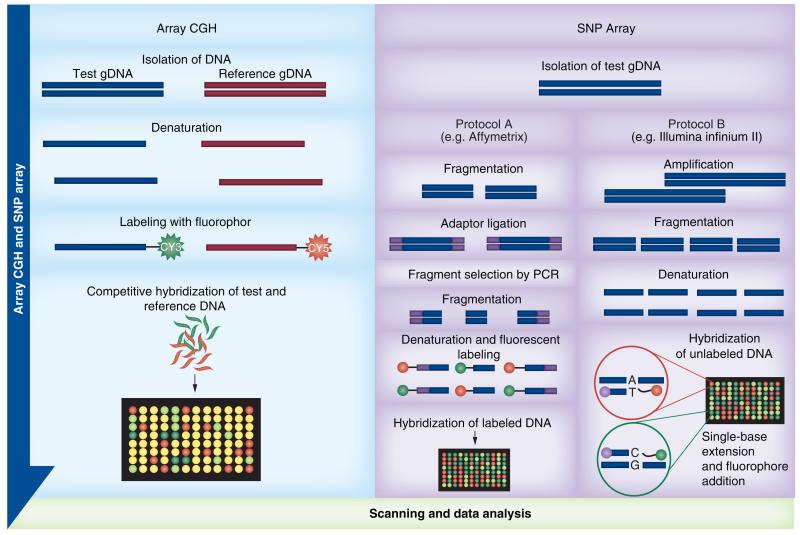

In CLL, our knowledge of CNAs and cnLOH/UPD has expanded greatly over recent years and this is attributable to the use of high-resolution genome-wide microarrays, which can assay both copy number and genotype [20,46]. Microarrays used for this purpose consist of a solid surface onto which probes mapping to known locations in the genome are applied in an array format. Until recently, there were two types of genomic microarrays: comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) arrays and SNP arrays (Figure 2) [48,54-56]. In a CGH array experiment, equal amounts of test and control DNAs are differentially labeled using different fluorophores, and cohybridized to oligonucleotide probes on the array. Deviations from a 1:1 fluorescence intensity ratio of hybridization between the samples are used to signpost changes in copy number in the test sample compared with the control. CGH array can detect common and rare or private familial CNVs, as well as CNAs [55,57,58].

Figure 2. Examples of array comparative genomic hybridization and SNP array workflows.

In array CGH both the test and reference DNA are hybridized together, whereas for SNP arrays, only the test DNA is hybridized.

CGH: Comparative genomic hybridization.

SNP arrays differ from CGH arrays in that the arrayed probes are oligonucleotides specifically designed to detect single nucleotide changes representing known polymorphisms. Furthermore, a SNP array experiment uses only the test sample [58]. The fluorescence data produced not only provides distinct genotype calls for each arrayed SNP (AA, AB or BB), but can also be used to compare against a control dataset, calculating fluorescence intensity ratios that, in turn, inform upon copy number. Whilst both CGH and SNP array data provide a visual indication of copy number through a log R ratio plot of fluorescence intensity data, only SNP array genotyping data can be used to plot B-allele frequency (BAF), allowing sensitive detection of cnLOH (where the Log R ratio is 0 [diploid] and all probes across a region are homozygous AA or BB). In addition, the BAF provides confirmation of copy number losses or gains suspected from the log R plot; a copy number loss results in LOH across the BAF plot, whereas a gain results in a series of probes with approximately 33 and 66% B alleles (i.e., ABB or AAB) [48,57,59,60]. A major advantage of SNP arrays compared with CGH arrays is the use of abnormal BAF patterns to detect mosaicism, including low-level mosaicism that passes undetected using the Log R data [61]. Mosaicism is intraindividual genetic heterogeneity due to the presence of two or more cell populations with different genotypes. Using SNP arrays, mosaicism may present as whole-chromosome aneuploidy, segmental aneuploidy or cnLOH, and can be detected in either germline or somatic DNA [61]. Somatic mosaicism found in CLL samples helps in the detection of different subclones in patients [46], although it is important to note that contamination of normal cells with abnormal test cells can give a similar pattern to mosaicism [62,63]. Algorithms/computational statistical tools have been developed that provide a measure of mosaicism within a tumor sample and these add to the utility of genome-wide SNP arrays. Examples include OncoSNP [46] and the and the latest version of Nexus Copy Number software from BioDiscovery Inc. (CA, USA), which combines two algorithms: the Genomic Identification of Significant Targets in Cancer algorithm for identification of significant regions of common genomic aberrations and the Allele-Specific Copy Number Analysis of Tumors algorithm which helps to address the issue of mosaicism and aneuploidy [201].

Recently, hybrid arrays that contain both SNPs and nonpolymorphic genomic probes have become available, combining the advantages of SNP and CGH arrays, for detecting cnLOH and CNVs/CNAs, respectively [46,47,64].

Microarray studies have been used to detect the recurrent alterations associated with CLL, such as TP53 and ATM mutations, and have revealed additional new recurrent alterations such as deletions involving 15q [47], 8p [65] and 22q [66], and gains involving 20q [67] and 2p [65]. Several array-based studies have suggested that the detection of specific CNAs can offer independent prognostic [47,68-70] or predictive [31,46,71,72] information, and have identified candidate driver genes. Distinguishing the driver candidate genes that drive CLL pathogenesis from random mutations that accumulate during disease progression is still a critical challenge in genomic array studies. However, defining recurrent minimal deleted/overlapping regions of change has identified candidate founder genes involved in many known cellular functions and pathways, including B-cell maturation, DNA damage response, tumor progression and familial CLL [46,47]. Moreover, genome-wide array screening of CLL samples has improved our understanding of genomic heterogeneity and the related clinical course, and identified genomic markers associated with poor prognosis. Genomic events are less frequent in CLL compared with other hematological malignancies, but at the same time, genomes of different CLL patients show huge heterogeneity of genomic complexity, as defined by size and number of CNAs [20,46,47]. Most TP53-mutated CLL shows genomic complexity. However, approximately two-thirds of CLL with genomic complexity are TP53 wild-type. Other genetic abnormalities found to associate with genomic complexity are del11q and large del13q14 inclusive of RB [20,31,46,49,65,69,71,73].

In addition to genomic complexity, clonal evolution over time is also associated with poor outcome [46]. We performed a two timepoints paired analysis of pretreatment and relapse samples from CLL patients using high-resolution SNP arrays, and the computational statistical tool OncoSNP [46]. This strategy helped us to track genomic changes related to disease progression and chemotherapy resistance, and allowed quantification of subclonal distribution of recurrent genomic aberration in the paired samples. In this study, increased clonal evolution was associated with poor outcome [46]. Another longitudinal array study of 22 CLL patients has noted an increase in genomic complexity and re-emergence of subclones at relapse and disease progression [74]. The study has also highlighted the advantages of evaluating genomic complexity by array and FISH analyses, rather than by FISH alone.

Comparisons between FISH and micro array results have been reported in several studies investigating the CLL genome [31,46,47,69,70,75,76]; the major advantage of arrays compared with FISH is that the whole CLL genome can be scanned for genomic aberrations in a single test as opposed to the limited abnormalities detectable using the FISH panel. Furthermore, while array results overlapped well with those obtained using FISH, some array-based CLL studies have detected aberrations that passed undetected by FISH. For example, a FISH CLL panel cannot detect cnLOH at 17p13.1 associated with homozygous TP53 mutations [31] or del11q abnormalities that do not involve ATM (where the 11q22.3 FISH probe hybridizes) [77,78]. Moreover, FISH assays of del11q22.3 and del13q14 often do not detect small deletions that microarrays do capture [47,70]. Truly balanced translocations are not detectable using microarrays. However, in CLL, such recurrent abnormalities are very rare, although they are associated with poor prognosis [72]. In the studies to date, FISH and SNP array results are up to 93% in accordance [46,47,70,75,78]. The discordance appears to largely depend on the probe density of the microarrays across regions not assayed by FISH and also the presence of subclonal aberrations below the threshold of microarray sensitivity, although this problem has been largely overcome by analysis of B-allele frequency plots. Other likely causes of disconcordance include lack of standardization of the array technologies used and interpretation.

Array testing provides additional independent prognostic information, especially in CLL cases with normal FISH [75], and has revolutionized not only our understanding of the extent of normal genetic variation (e.g.,dbSNP [79], HapMap project [80], Database of Genomic Variation [81] and dbVAR [82]), but also of many genomic disorders. However, array-based studies alone cannot identify every genetic determinant of a condition and in the future we believe it likely that array technology and FISH will be replaced by next-generation sequencing (NGS), which, it is thought, will overcome disadvantages associated with both microarrays and FISH, and will provide an alternative method of studying genomic complexity and subclonal evolution. NGS has the capability to directly assay every base of the genome, detecting single base mutations, as well as CNVs/CNAs, and regions of cnLOH, and the approach also minimizes experimental-associated bias [83]. Although currently available array data is still substantially stronger than that of the few published NGS studies so far, technical advantages of NGS, regardless of cost–effectiveness, make it a more attractive approach for the future, for identifying and validating predictive, as well as prognostic, CLL genomic markers. In the next section, we will therefore review the different NGS modalities and their potential clinical applications in CLL.

Next-generation sequencing

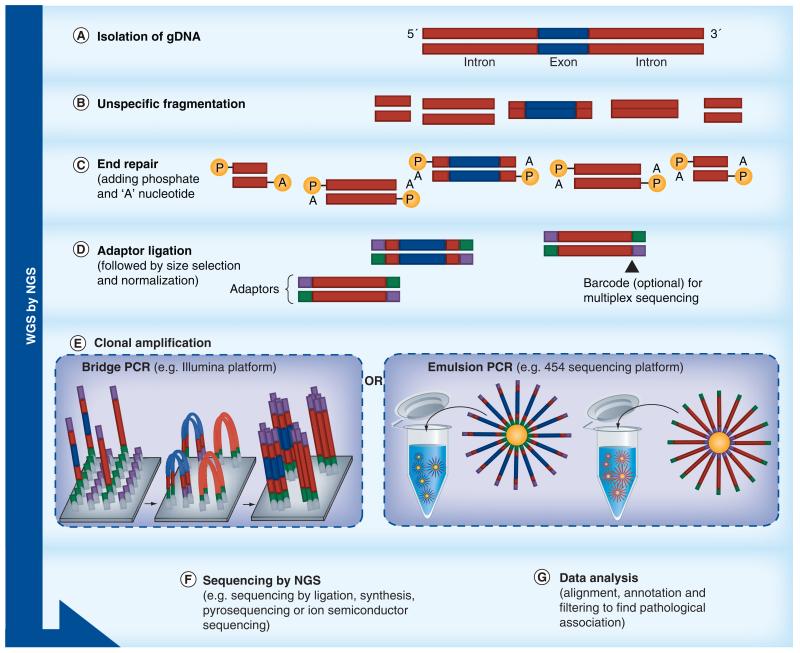

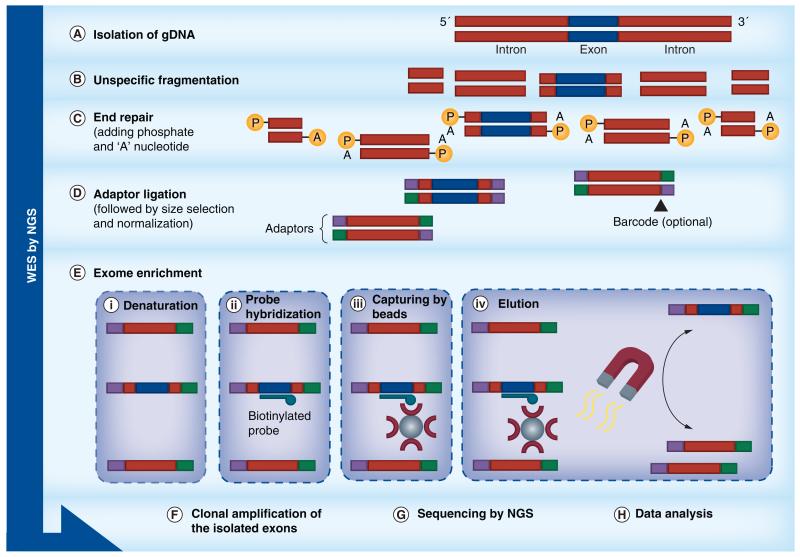

The development of massively parallel sequencing and new sequencing chemistry, such as sequencing by synthesis and by ligation, have led to different sequencing platforms (Figures 3-6), and independent innovations in automation, imaging, microprocessing and nanotechnology [83]. In NGS terminology, the ability to sequence the entire genome, including exons and introns, is referred to as whole-genome sequencing (WGS), while determining the sequence of protein-coding sequences (exons) of the whole genome is referred to as whole-exome sequencing (WES). NGS can also be applied for sequencing panels of genes known to be involved in a particular disease, so-called targeted gene sequencing (TGS) [84].

Figure 3. Basic principles and workflows of the technical applications of next-generation sequencing.

Overview of workflows of NGS technologies: WGS; the aim is to capture and sequence exonic and intronic sequences representing the entire genome.

NGS: Next-generation sequencing; WGS: Whole-genome sequencing.

Figure 4. Basic principles and workflows of the technical applications of next-generation sequencing.

Overview of workflows of NGS technologies: WES; the aim is to capture only the coding regions of genes. The approach is similar to whole-genome sequencing except that an exon enrichment step is performed using biotinylated probes specifically designed to exon sequences.

NGS: Next-generation sequencing; WES: Whole-exome sequencing.

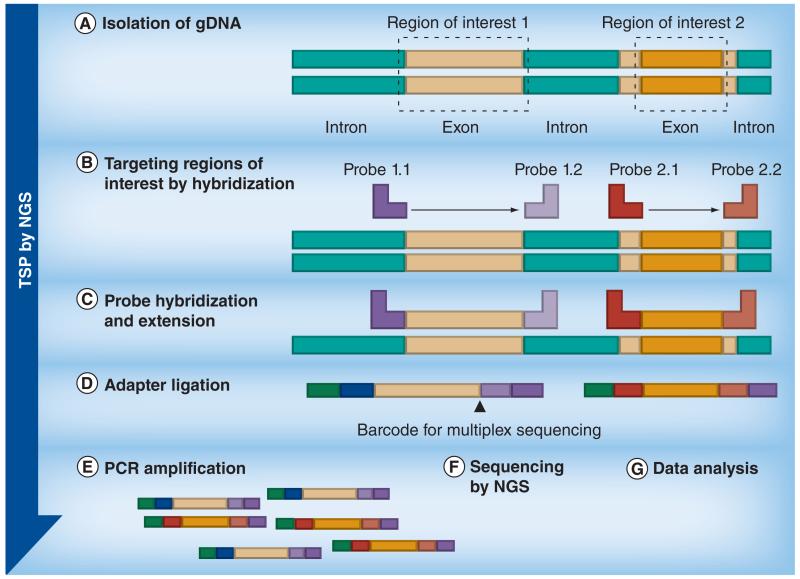

Figure 5. Basic principles and workflows of the technical applications of next-generation sequencing.

Overview of workflows of NGS technologies: Targeted gene sequencing using TSPs; the aim is to only sequence specific genes or sequences of interest. Primers specific to sequences flanking the target regions are hybridized to fragmented test DNA and following extension, ligation and PCR, the amplified products (the target amplicons) are sequenced.

NGS: Next-generation sequencing; TSP: Targeted sequencing panel.

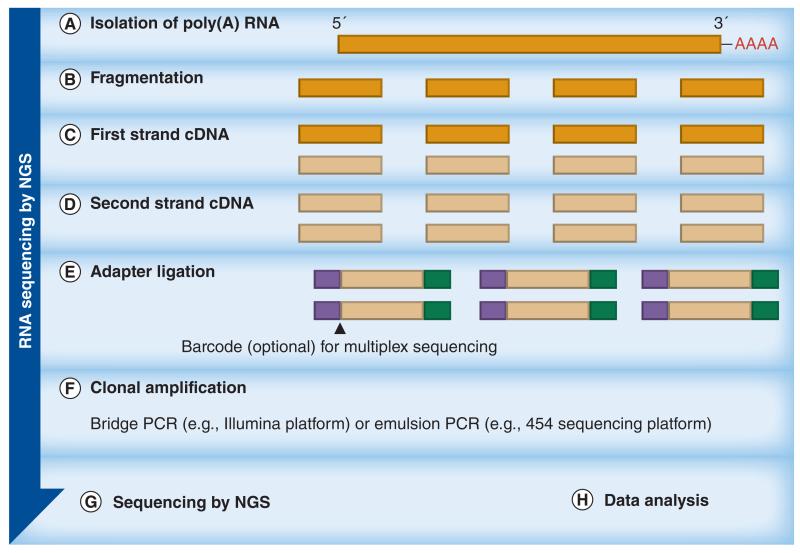

Figure 6. Basic principles and workflows of the technical applications of next-generation sequencing.

Overview of workflows of NGS technologies: RNA sequencing; the aim is to only sequence transcribed regions of the genome. The approach is similar to whole-genome sequencing except that the template is cDNA generated following RNA extraction and isolation of poly(A) RNA.

NGS: Next-generation sequencing.

WGS versus WES

In humans, the exome represents 1% of the whole genome. Therefore, potential causal variants (i.e., variants that might cause disease) located in noncoding regions of the genome (e.g., splice sites, promoter regions and most mRNAs) cannot be detected by WES. WGS is more likely to capture these types of variants, as well as reveal structural variants, including translocations. However, allele frequencies in WGS are lower [84], whereas WES shows greater coverage depth for targeted coding sequences and so is more sensitive than WGS across these regions (Table 1) [85]. WES yields depend on the efficiency of the capture probes used for library preparation. This varies considerably and it is estimated that up to 20% of the exome is not captured by standard WES [86]. Importantly, WES remains more affordable, especially when considering large sample size, and thus it is more often applied than WGS [84]. Perhaps the only disadvantage of NGS compared with traditional Sanger sequencing, in addition to cost, is the production of shorter-length reads, with the subsequent generation of greater amounts of data. NGS requires sophisticated bioinformatics tools for data analysis and clinical interpretation in order to alleviate the complexities of data interpretation [87], and it remains a challenge to distinguish true variants from sequencing errors, and nonpathogenic variants [88]. Therefore, further improvements in informatics pipelines will play an essential role in enabling NGS to move from being a research tool to a predictive diagnostic device. In addition, more studies comparing WGS and WES are needed before it can be decided exactly which method will be implemented in this way.

Table 1. Comparison of different types of data provided by molecular techniques.

| Data type | Large-scale structural changes† | Balanced translocations | Distant consanguinity | Uniparental disomy | Novel coding variants | Novel noncoding variants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FISH | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| TSP | No | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| SNP arrays | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| CGH array | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| WES | Partial | No | Partial | Partial | Yes | No |

| WGS | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Excluding balanced translocations.

CGH: Comparative genomic hybridization; TSP: Targeted sequencing panel; WES: Whole-exome sequencing; WGS: Whole-genome sequencing.

WES & WGS studies of CLL

Recent studies using NGS in CLL have provided novel insights into the pathogenesis of the disease. The first WGS analysis of CLL was performed using samples from four CLL patients. This revealed over 1000 somatic mutations in nonrepetitive regions per sample and a total of 46 somatic mutations affecting 45 protein-coding genes. Among the 46 mutations, only mutations in NOTCH1, MYD88, XPO1 and KLHL6 were identified as recurrent in the larger validation set of CLL patients [15]. A subsequent WES study of five newly diagnosed and untreated CLL patients detected 40 somatic mutations affecting 39 protein-coding genes. Mutations involving NOTCH1 were found to be recurrent in a larger cohort of patients (n = 48) [89]. Interestingly, in this study, NOTCH1 mutations were not detected by WES, but by targeted re-sequencing. Results of both studies were confirmed by Sanger sequencing and SNP arrays, and provided the first snapshot of the complex genomic single nucleotide changes present in CLL at a particular timepoint.

The use of NGS to investigate the genomic complexity of CLL at the single nucleotide level has also led to the identification of novel recurrent mutations in the genes SF3B1 [90,91] and BIRC3 [89], as well as NOTCH1 [15,89,91]; each of these are discussed further in the next section. NGS has also provided new insights into the role of subclonal evolution in CLL heterogeneity [16,92].

NOTCH1

The NOTCH1 gene encodes the NOTCH1 receptor, which is a member of the transmembrane protein family and functions as a ligand-activated transcription factor, playing an important role in fundamental cellular functions, including cell differentiation, proliferation and apoptosis. Not surprisingly, any alteration in this signaling may cause abnormal cellular activities. Mutations of NOTCH1 were first discovered through the analysis of the chromosomal translocation t(7;9)(q34;q34.3) in patients with T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) [93].

Many studies have used NGS and/or Sanger sequencing, and all have found that NOTCH1 mutations appear to be an independent poor prognostic factor in CLL [91,94-97]. Whereas the role of NOTCH1 mutations in the leukemogenesis of T-ALL is well described, their effect on CLL pathogenesis remains to be determined, although an antiapoptotic role has been proposed [98,99]. Patients with NOTCH1 mutations have a more advanced clinical stage at diagnosis and shorter survival probability compared with patients with NOTCH1 wild-type [15,89,94]. For example, Puente et al. reported an overall survival rate of 21% in NOTCH1-mutated cases versus 56% in NOTCH1 wild-type cases at 10 years [15]. In a hierarchical model proposed by Rossi et al. [95], cases harboring NOTCH1 and/or SF3B1 mutations, and/or del11q22-q23 were classified as intermediate risk [95]. This intermediate-risk prediction was also recently confirmed by data from the UK LRF CLL4 trial [100].

Interestingly, the frequency of NOTCH1 mutations in unselected and untreated CLL patients was reported to be 4–6% [91], and appears to be higher (~15–30%) in chemotherapy-refractory CLL, progressive CLL and CLL transformation to Richter’s syndrome [15,89,94,101], compared with selective cohort [15,102]. The most common mutation in all investigated CLL cases (~80% of NOTCH1 mutations) was a small, recurrent, 2 bp frameshift deletion (ΔCT7544–7545, P2515fs) within exon 34, which can disrupt the C-terminal PEST domain and deregulate NOTCH1 signaling [15,89,90,94,96,97,103,104]. Other types of mutations, although rare, were associated with the same adverse impact [15,89,94,101].

NOTCH1 mutations tend to cluster with trisomy 12, mainly when the latter is expressed as the sole cytogenetic abnormality [94,96,100,101,105]. Whether NOTCH1 mutations are founders or occur at later stages of CLL evolution remains an open question. Fabbri et al. noted that five out of 16 NOTCH1 mutations were not present at time of diagnosis, but they were detected in Richter’s syndrome transformation, while another five NOTCH1 mutations were detected at time of diagnosis, but at the subclonal level [89]. By contrast, Villamor et al. observed that NOTCH1 mutations were stable over time and only 0.5% of CLL patients acquired a mutation in NOTCH1 through the course of the disease [101].

In conclusion, the clinical significance of NOTCH1 mutations is currently inconclusive and must be formally further assessed within clinical trials. Recent data from the CLL8 trial showed that FCR treatment appeared to be unbeneficial to CLL patients who harbor a NOTCH1 mutation, whereas the outcome of using the FCR combination was satisfactory in patients lacking this mutation [106]. Different NOTCH1 inhibitors have been under clinical investigation. NOTCH1 signaling was targeted in T-ALL clinical trials by γ-secretase inhibitors (MK-0752), but the approach was not well-tolerated due to unexpected gastrointestinal toxicity. However, in vitro studies using the γ-secretase inhibitor to induce apoptosis of CLL cells showed promising results [107].

Since this time, 353 WES results from CLL patient samples have been published and these demonstrate that the majority of mutations in CLL are either nonrecurrent or occur at low frequency (<5%) [90,92,97]. These studies convincingly showed that proteins involved in RNA splicing, in particular SF3B1, are affected by recurrent mutations [90,97]. Other recurrent abnormalities in CLL that have been recently reported from NGS studies involved the BIRC3 gene [89].

SF3B1

The SF3B1 protein is involved in the binding of the spliceosomal U2 snRNP to the branch point close to 30 splicing sites of mRNA [108]. Recurrent SF3B1 mutations in CLL were mainly missense mutations that are clustered in hotspot codons 662, 666 and 700 [90,97].

Similar to NOTCH1, SF3B1 mutations are associated with intermediate-risk prognosis [90,91,95]. The frequency of SF3B1 mutations was higher in CLL patients who had multiple treatments than those who were first diagnosed [95,109]. The two timepoint analysis showed that subclones harboring SF3B1 mutations can spontaneously increase with disease progression [92,95,109]. Intriguingly, SF3B1 mutations were also reported in refractory anemia with ring sideroblast myelodysplastic syndrome, where they are associated with relatively good prognosis and longer survival [108,110].

BIRC3

The BIRC3 gene product is a member of the inhibitors of apoptosis ‘IAP’ family of proteins and thought to negatively regulate anti-apoptotic transcription factor NF-κB cells [111]. It is encoded at chromosome 11q22.2, approximately 6 Mb proximal to the ATM gene [202]. Del11q is itself one of the most common chromosomal aberrations in CLL and is associated with rapid disease progression and shorter overall survival [10,112,113]. Recurrent aberrations in BIRC3 have been reported in CLL [89,111] and may be associated with poor prognosis similar to the outcomes associated with TP53 abnormalities [111]. BIRC3 disruption, either through mutations or mono- or bi-allelic deletion, has been nominated as a candidate driver of abnormality in CLL cases with atypical del11q (del11q with an intact ATM gene). Similar to SF3B1 and NOTCH1, the frequency of BIRC3 abnormalities is higher in previously treated patients [111]. In 1274 analyzed CLL samples, BIRC3 deletion/mutations were classified as independent high-risk prognostic factors, similar to TP53 abnormalities [95]. Moving forward, disruption of the BIRC3 gene might provide a molecular rationale for targeting NF-κB signaling in CLL [114,115]; whether it is of predictive value will be validated in future studies.

Outstanding molecular questions in CLL

Despite the progress that has been made in the molecular characterization of CLL, important questions remain to be answered:

-

■

Are the mutations identified (whether nonrecurrent or recurrent) drivers or passengers of CLL pathogenesis and maintenance?

-

■

What are the molecular changes that occur in individual patients undergoing therapy?

-

■

Can WGS mutation profiles be used to predict a patient’s response to treatment?

Modern concepts of tumor biology propose that malignant disease is characterized by genomic instability and the Darwinian process of clonal evolution and selection. This fact has been recently supported by results from studies comparing sequence data from primary and metastatic tumor samples, or from multiple locations within a tumor, which reveal considerable heterogeneity of somatic mutation profiles in tumors at different disease stages and timepoints [116-118]. In our study of CLL, we analyzed five sequential leukemia samples, obtained over a period of up to 7 years, from three CLL patients who received multiple rounds of treatment [16]. In each sample, somatic mutations were in the range of 1744–2829 substitutions and 204–385 insertions/deletions; although only between 14 and 22 mutations per sample were predicted to alter protein-coding sequences. WGS analysis detected all CNAs noted in a previous array-based study and revealed additional small CNAs. All three cases showed distinct recurrent mutations. The variant allele frequency either changed or remained stable over time. At all timepoints, targeted deep sequencing was used to track the change in subclonal population in response to therapy, showing two cases with four subclones and one case with the most dynamic profiles of five subclones.

We hypothesized that mutations present in all tumor cells at all timepoints represented founder events. Interestingly, some recurrent mutations, for example in ATM or IRF4, were clearly secondary events, as they were not observed in all tumor cells. In addition, some subclones containing recurrent mutations, such as ATM, were not detectable after treatment. Conversely, we also observed nonrecurrent mutations of defined pathogenicity such as an activating mutation in MEK1 that was part of the expanding subclone that dominated at the time of death. Importantly, emerging subclones only occurred in the two heavily pretreated patients who subsequently died, whereas the patient with stable mutation profiles never received any chemotherapy and is still alive [16].

In the same study, we provided evidence from targeted deep sequencing that chemotherapy might ablate chemotherapy-sensitive clones, but that it also induces additional mutations responsible for subsequent chemotherapy resistance [16].

This pilot data led us to hypothesize that stable mutation profiles predict response to treatment and good prognosis, whereas emerging or increasing subclone events reflect treatment resistance and rapid disease progression [16]. This hypothesis has been further substantiated in recent data from Landau et al. who performed WES for 160 CLL tumor/normal pairs [92]. For 149 of the 160 cases where both CNAs and WES data were available, integrative analysis of somatic CNAs and somatic single nucleotide variation (sSNV) was performed [92]. Each clonal (>0.5) and subclonal (<0.5) sSNV was classified based on probability that its cancer cell fraction was >0.95. To infer temporal ordering of the recurrent sSNVs and CNAs, the authors suggested that early events are the predominant clonal mutations affecting a specific gene or chromosomal lesion, while the later events are the common locus-specific subclonal mutations that represent additional mutations [92]. Accordingly, three early driver abnormalities were identified, including MYD88 mutations, trisomy 12 and hemizygous del13q. In longitudinal analysis of the 18 cases, clustering analysis of cancer cell fraction distribution of each genomic abnormality over the two timepoints showed clear clonal evolution involving subclones with driver mutations in ten out of 12 CLL patients treated with chemotherapy and one out of six untreated patients. The presence of subclonal driver mutations showed an adverse impact on clinical outcome and therefore might be considered an independent poor prognostic factor of relapse and disease progression[92].

The Landau et al. study represents a comprehensive analysis of subclonal and clonal mutations present in the exomes of CLL patients. The integrative analysis of WES and CNAs provides a cost-effective and sensitive strategy for overcoming the small sample size of the published multitimepoint analysis and confirms that relapse might in fact be due to a disruption of the subclonal equilibrium. In addition, the potential hastening of the evolutionary process with treatment provides a mechanistic justification for the empirical practice of ‘watch and wait’ as a CLL treatment paradigm. However, the results need to be confirmed within clinical trials and only WGS using PCR-free protocols will allow the precise definition of the subclonal composition from variant allele frequencies of exonic and intronic mutations.

Targeted gene sequencing

TGS using targeted sequencing panels allows known mutations associated with a particular disease to be identified at comparatively low cost and without the complex bioinformatics required to analyse WES and WGS data. The benchtop platforms currently available can be used in a clinical setting and facilitate ultra-deep sequencing with high depth of coverage, allowing the detection of specific genetic abnormalities, even at subclonal level [16,119]. Recent NGS using the targeted sequencing panel approach has revealed new mutations in CLL that are related to B-cell receptor signaling and related pathways, including KRAS, SMARCA2, NFKBIE and PRKD3 genes [120]. It is likely that, once validated, targeted mutation panels will be implemented in clinical diagnostics until the time that whole-genome approaches become price-competitive.

Conclusion

Novel technologies offer significant potential for response prediction and selection of treatment. However, until they have been further evaluated, current clinical decision-making should still rely on the combination of FISH and conventional Sanger sequencing to detect del17p13.1 and/or TP53 mutations, and this should be repeated before any line of treatment [33]. Patients with TP53 abnormalities should be offered chemotherapy-free agents and/or entry into clinical trials. Younger patients might be considered for allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. In addition, the detection of del11q indicates a need for adding rituximab to the chemotherapy backbone [8].

The introduction of genome-wide technologies into clinical diagnostics faces significant challenges. Assay development, technical validation and standardization and assessment of clinical utility within clinical trials must be combined with cost–effectiveness and –benefit analyses. These must take into account patient preference and cost savings from avoiding side-effects caused by ineffective drugs. Targeted multigene panels in combination with genome arrays will certainly have a medium-term role as the first choice in the diagnostic algorithm; however, only WGS has the capability to detect all genomic abnormalities. The wider adoption of WGS will require reduction in the cost per genome and our understanding of the clinical value of WGS needs to be systematically explored in clinical trials of larger patient cohorts. Further longitudinal WGS analysis of individual cancer patients going through treatment will be necessary to derive maximum benefit from this new technology. Improvement of bioinformatics tools will drive its implementation for cancer diagnosis and response prediction. The extensive genotypic data has to be linked to deep clinical outcome data across large patient populations in genotype–phenotype databases. Specialist diagnostic centers with the scientific, clinical and bioinformatics expertise will need to initiate these developments. Eventually, we hope that the identification of the molecular footprint of individual cancers will lead to targeted treatment and improved clinical outcomes for patients suffering from malignant diseases.

Future perspective

Identifying the individual molecular footprint of malignancies and monitoring disease progression systematically and prospectively by whole-genome technologies appears as an effective future strategy to predict treatment response in CLL and other tumors, and may direct future clinical trials and therapeutic decisions. It remains to be seen whether molecular features will preserve their prognostic and predictive value with newly emerging classes of drugs such as the B-cell receptor inhibitors [121]. Technical and clinical evaluation, and rigorous standardization of currently available library preparations and bioinformatics pipelines will have to be accompanied by improvements in turnaround time, evaluation of cost:benefit ratio and interpretation of bioinformatics data within clinical trials before unbiased genome-wide approaches can be used in diagnostics.

Executive summary.

Background

-

■

Important progress has been made in the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), especially with the introduction of chemoimmunotherapy.

-

■

None of the available conventional treatment options are curative and approximately 25 and 50% of patients relapse within 2 years from first- or second-line therapy, respectively.

-

■

It is important to differentiate predictive from prognostic biomarkers.

-

■

TP53 deletions and/or mutations involving chromosome 17p13.1 are widely accepted as biomarkers of poor CLL outcome and are considered to be important predictive biomarkers for chemorefractoriness.

-

■

TP53 mutations in the absence of del17p have the same adverse impact on survival, but cannot be detected using FISH.

Genomic microarrays to detect somatically acquired copy number alterations & SNPs

-

■

Copy number variants (CNVs) have been defined as DNA segments of at least 1 kb in size in which a comparison of two or more genomes reveals gains or losses of copy number relative to the reference genome.

-

■

In addition to CNVs, SNPs determine the general genetic variation among populations.

-

■

Acquired or somatic copy number alterations tend to be larger than CNVs and are associated with malignancies such as CLL.

-

■

Our knowledge of copy number alterations and copy-neutral loss of heterozygosity/uniparental isodisomy in CLL has greatly expanded through the use of high-resolution genome-wide microarrays, which can assay both copy number and genotype SNPs.

-

■

Specific aberrations and genomic complexity associated with poor clinical outcome have been identified using genome-wide arrays.

-

■

In the future, it is thought that array technology will be replaced by next-generation sequencing technology.

Next-generation sequencing

-

■

Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) can detect sequence variants that whole-exome sequencing (WES) cannot.

-

■

WES is more affordable and has greater depth than WGS.

-

■

Rigorous validation and standardization of WGS and WES are needed before implementation as tools for treatment response prediction.

-

■

Next-generation sequencing has promoted the investigation of genomic complexity in CLL at the single nucleotide level, leading to the identification of novel recurrent mutations such as those found in NOTCH1, SF3B1 and BIRC3.

-

■

Important questions remain regarding the biological and clinical significance of driver and passenger events, and the clinical utility of WGS for response prediction to treatment.

Acknowledgments

Financial & competing interests disclosure

R Alsolami, SJL Knight and A Schuh are supported by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, Oxford (UK) with funding from the Department of Health’s NIHR Biomedical Research Centres funding scheme. In addition, SJL Knight and A Schuh are supported by the Health Innovation Challenge Fund (HICF-1009–026), a parallel funding partnership between the Wellcome Trust and the Department of Health. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Health or the Wellcome Trust. SJL Knight is also supported by the Wellcome Trust Core Award Grant [090532/Z/09/Z] and R Alsolami by King Abdulaziz University (Saudi Arabia) Faculty of Applied Medical Sciences. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

■ of interest

■■ of considerable interest

- 1.Vardiman JW, Harris NL, Brunning RD. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of the myeloid neoplasms. Blood. 2002;100(7):2292–2302. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Estey EH. Acute myeloid leukemia: 2012 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and management. Am. J. Hematol. 2012;87(1):89–99. doi: 10.1002/ajh.22246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sullivan C, Peng C, Chen Y, Li D, Li S. Targeted therapy of chronic myeloid leukemia. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2010;80(5):584–591. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tallman MS, Brenner B, Serna Jde L, et al. Meeting report. Acute promyelocytic leukemia-associated coagulopathy, 21 January 2004, London, United Kingdom. Leuk. Res. 2005;29(3):347–351. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2004.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howlader N, Noone A, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review 1975–2009 (Vintage 2009 Populations) National Cancer Institute; MD, USA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zenz T, Mertens D, Kuppers R, Dohner H, Stilgenbauer S. From pathogenesis to treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2010;10(1):37–50. doi: 10.1038/nrc2764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clifford R, Schuh A. State-of-the-art management of patients suffering from chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Clin. Med. Insights Oncol. 2012;6:165–178. doi: 10.4137/CMO.S6201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hallek M, Fischer K, Fingerle-Rowson G, et al. Addition of rituximab to fludarabine and cyclophosphamide in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a randomised, open-label, Phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9747):1164–1174. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61381-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robak T, Dmoszynska A, Solal-Celigny P, et al. Rituximab plus fludarabine and cyclophosphamide prolongs progression-free survival compared with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide alone in previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;28(10):1756–1765. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.4556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dohner H, Stilgenbauer S, Benner A, et al. Genomic aberrations and survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000;343(26):1910–1916. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012283432602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dohner H, Stilgenbauer S, Fischer K, Bentz M, Lichter P. Cytogenetic and molecular cytogenetic analysis of B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: specific chromosome aberrations identify prognostic subgroups of patients and point to loci of candidate genes. Leukemia. 1997;11(Suppl. 2):S19–S24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klein U, Lia M, Crespo M, et al. The DLEU2/miR-15a/16–1 cluster controls B cell proliferation and its deletion leads to chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2010;17(1):28–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zenz T, Eichhorst B, Busch R, et al. TP53 mutation and survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;28(29):4473–4479. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.8762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stankovic T, Kidd AM, Sutcliffe A, et al. ATM mutations and phenotypes in ataxiatelangiectasia families in the British Isles: expression of mutant ATM and the risk of leukemia, lymphoma, and breast cancer. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1998;62(2):334–345. doi: 10.1086/301706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Puente XS, Pinyol M, Quesada V, et al. Whole-genome sequencing identifies recurrent mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Nature. 2011;475(7354):101–105. doi: 10.1038/nature10113. [■■ First whole-genome study of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) that revealed novel mutations, including NOTCH1.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schuh A, Becq J, Humphray S, et al. Monitoring chronic lymphocytic leukemia progression by whole genome sequencing reveals heterogeneous clonal evolution patterns. Blood. 2012;120(20):4191–4196. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-433540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cramer P, Hallek M. Prognostic factors in chronic lymphocytic leukemia – what do we need to know? Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2011;8(1):38–47. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oldenhuis CN, Oosting SF, Gietema JA, de Vries EG. Prognostic versus predictive value of biomarkers in oncology. Eur. J. Cancer. 2008;44(7):946–953. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zenz T, Frohling S, Mertens D, Dohner H, Stilgenbauer S. Moving from prognostic to predictive factors in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) Best Pract. Res. Clin. Haematol. 2010;23(1):71–84. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malek SN. The biology and clinical significance of acquired genomic copy number aberrations and recurrent gene mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Oncogene. 2012 doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.411. doi:10.1038/onc.2012.411. Epub ahead of print. [■■ Comprehensive review of the genomic complexity of CLL.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hillmen P. Using the biology of chronic lymphocytic leukemia to choose treatment. Hematology Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program. 2011;2011:104–109. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2011.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moreno C, Montserrat E. New prognostic markers in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood Rev. 2008;22(4):211–219. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dohner H, Fischer K, Bentz M, et al. p53 gene deletion predicts for poor survival and non-response to therapy with purine analogs in chronic B-cell leukemias. Blood. 1995;85(6):1580–1589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Catovsky D, Richards S, Matutes E, et al. Assessment of fludarabine plus cyclophosphamide for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (the LRF CLL4 trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;370(9583):230–239. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61125-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grever MR, Lucas DM, Dewald GW, et al. Comprehensive assessment of genetic and molecular features predicting outcome in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: results from the US Intergroup Phase III trial E2997. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007;25(7):799–804. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saddler C, Ouillette P, Kujawski L, et al. Comprehensive biomarker and genomic analysis identifies p53 status as the major determinant of response to MDM2 inhibitors in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2008;111(3):1584–1593. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-112698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malcikova J, Smardova J, Rocnova L, et al. Monoallelic and biallelic inactivation of TP53 gene in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: selection, impact on survival, and response to DNA damage. Blood. 2009;114(26):5307–5314. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-234708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zenz T, Habe S, Denzel T, et al. Detailed analysis of p53 pathway defects in fludarabinerefractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL): dissecting the contribution of 17p deletion, TP53 mutation, p53-p21 dysfunction, and miR34a in a prospective clinical trial. Blood. 2009;114(13):2589–2597. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-224071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rossi D, Cerri M, Deambrogi C, et al. The prognostic value of TP53 mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia is independent of Del17p13: implications for overall survival and chemorefractoriness. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009;15(3):995–1004. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oscier D, Wade R, Davis Z, et al. Prognostic factors identified three risk groups in the LRF CLL4 trial, independent of treatment allocation. Haematologica. 2010;95(10):1705–1712. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2010.025338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ouillette P, Collins R, Shakhan S, et al. Acquired genomic copy number aberrations and survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2011;118(11):3051–3061. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-327858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gonzalez D, Martinez P, Wade R, et al. Mutational status of the TP53 gene as a predictor of response and survival in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: results from the LRF CLL4 trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29(16):2223–2229. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.0838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pospisilova S, Gonzalez D, Malcikova J, et al. ERIC recommendations on TP53 mutation analysis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2012;26(7):1458–1461. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oscier D, Dearden C, Erem E, et al. Guidelines on the diagnosis, investigation and management of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br. J. Haematol. 2012;159(5):541–564. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Skowronska A, Parker A, Ahmed G, et al. Biallelic ATM inactivation significantly reduces survival in patients treated on the United Kingdom Leukemia Research Fund Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia 4 trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012;30(36):4524–4532. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.41.0852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsimberidou AM, Tam C, Abruzzo LV, et al. Chemoimmunotherapy may overcome the adverse prognostic significance of 11q deletion in previously untreated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer. 2009;115(2):373–380. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dewald GW, Brockman SR, Paternoster SF, et al. Chromosome anomalies detected by interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization: correlation with significant biological features of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br. J. Haematol. 2003;121(2):287–295. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shanafelt TD, Witzig TE, Fink SR, et al. Prospective evaluation of clonal evolution during long-term follow-up of patients with untreated early-stage chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006;24(28):4634–4641. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.9492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oscier DG, Gardiner AC, Mould SJ, et al. Multivariate analysis of prognostic factors in CLL: clinical stage, IGVH gene mutational status, and loss or mutation of the p53 gene are independent prognostic factors. Blood. 2002;100(4):1177–1184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zenz T, Krober A, Scherer K, et al. Monoallelic TP53 inactivation is associated with poor prognosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: results from a detailed genetic characterization with long-term follow-up. Blood. 2008;112(8):3322–3329. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-154070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stilgenbauer S, Zenz T, Winkler D, et al. Subcutaneous alemtuzumab in fludarabine-refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia: clinical results and prognostic marker analyses from the CLL2H study of the German Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Study Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27(24):3994–4001. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pettitt AR, Jackson R, Carruthers S, et al. Alemtuzumab in combination with methylprednisolone is a highly effective induction regimen for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia and deletion of TP53: final results of the national cancer research institute CLL206 trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012;30(14):1647–1655. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.9695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khaja R, Zhang J, Macdonald JR, et al. Genome assembly comparison identifies structural variants in the human genome. Nat. Genet. 2006;38(12):1413–1418. doi: 10.1038/ng1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Redon R, Ishikawa S, Fitch KR, et al. Global variation in copy number in the human genome. Nature. 2006;444(7118):444–454. doi: 10.1038/nature05329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beroukhim R, Mermel CH, Porter D, et al. The landscape of somatic copy-number alteration across human cancers. Nature. 2010;463(7283):899–905. doi: 10.1038/nature08822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Knight SJ, Yau C, Clifford R, et al. Quantification of subclonal distributions of recurrent genomic aberrations in paired pretreatment and relapse samples from patients with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2012;26(7):1564–1575. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Edelmann J, Holzmann K, Miller F, et al. High-resolution genomic profiling of chronic lymphocytic leukemia reveals new recurrent genomic alterations. Blood. 2012;120(24):4783–4794. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-423517. [■ The researchers applied SNP array to identify copy number alteration, genomic complexity and chromothripsis. Chromothripsis is recently described as a mechanism of tumorigenesis and is mainly found in cells harboring complex genomic rearrangements.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hagenkord JM, Monzon FA, Kash SF, Lilleberg S, Xie Q, Kant JA. Array-based karyotyping for prognostic assessment in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: performance comparison of Affymetrix 10K2.0, 250K Nsp, and SNP6.0 arrays. J. Mol. Diagn. 2010;12(2):184–196. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2010.090118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lehmann S, Ogawa S, Raynaud SD, et al. Molecular allelokaryotyping of early-stage, untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer. 2008;112(6):1296–1305. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zenz T, Benner A, Dohner H, Stilgenbauer S. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia and treatment resistance in cancer: the role of the p53 pathway. Cell Cycle. 2008;7(24):3810–3814. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.24.7245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gunnarsson R, Staaf J, Jansson M, et al. Screening for copy-number alterations and loss of heterozygosity in chronic lymphocytic leukemia – a comparative study of four differently designed, high resolution microarray platforms. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2008;47(8):697–711. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Conlin LK, Thiel BD, Bonnemann CG, et al. Mechanisms of mosaicism, chimerism and uniparental disomy identified by single nucleotide polymorphism array analysis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010;19(7):1263–1275. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tuna M, Knuutila S, Mills GB. Uniparental disomy in cancer. Trends Mol. Med. 2009;15(3):120–128. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tan DS, Lambros MB, Natrajan R, Reis-Filho JS. Getting it right: designing microarray (and not ‘microawry’) comparative genomic hybridization studies for cancer research. Lab. Invest. 2007;87(8):737–754. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barrett MT, Scheffer A, Ben-Dor A, et al. Comparative genomic hybridization using oligonucleotide microarrays and total genomic DNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101(51):17765–17770. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407979101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang L, Znoyko I, Costa LJ, et al. Clonal diversity analysis using SNP microarray: a new prognostic tool for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Genet. 2011;204(12):654–665. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Miecznikowski JC, Gaile DP, Liu S, Shepherd L, Nowak N. A new normalizing algorithm for BAC CGH arrays with quality control metrics. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2011;2011:860732. doi: 10.1155/2011/860732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alkan C, Coe BP, Eichler EE. Genome structural variation discovery and genotyping. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011;12(5):363–376. doi: 10.1038/nrg2958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gunderson KL, Steemers FJ, Lee G, Mendoza LG, Chee MS. A genome-wide scalable SNP genotyping assay using microarray technology. Nat. Genet. 2005;37(5):549–554. doi: 10.1038/ng1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Oliphant A, Barker DL, Stuelpnagel JR, Chee MS. BeadArray technology: enabling an accurate, cost–effective approach to high-throughput genotyping. BioTechniques. 2002;(Suppl. 56-58):60–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Biesecker LG, Spinner NB. A genomic view of mosaicism and human disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2013;14(5):307–320. doi: 10.1038/nrg3424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gonzalez JR, Rodriguez-Santiago B, Caceres A, et al. A fast and accurate method to detect allelic genomic imbalances underlying mosaic rearrangements using SNP array data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:166. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Markello TC, Carlson-Donohoe H, Sincan M, et al. Sensitive quantification of mosaicism using high density SNP arrays and the cumulative distribution function. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2012;105(4):665–671. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2011.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bruno DL, Stark Z, Amor DJ, et al. Extending the scope of diagnostic chromosome analysis: detection of single gene defects using high-resolution SNP microarrays. Hum. Mutat. 2011;32(12):1500–1506. doi: 10.1002/humu.21581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Grubor V, Krasnitz A, Troge JE, et al. Novel genomic alterations and clonal evolution in chronic lymphocytic leukemia revealed by representational oligonucleotide microarray analysis (ROMA) Blood. 2009;113(6):1294–1303. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-158865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gunn SR, Bolla AR, Barron LL, et al. Array CGH analysis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia reveals frequent cryptic monoallelic and biallelic deletions of chromosome 22q11 that include the PRAME gene. Leuk. Res. 2009;33(9):1276–1281. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rodriguez AE, Robledo C, Garcia JL, et al. Identification of a novel recurrent gain on 20q13 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia by array CGH and gene expression profiling. Ann. Oncol. 2012;23(8):2138–2146. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sellick GS, Wade R, Richards S, Oscier DG, Catovsky D, Houlston RS. Scan of 977 nonsynonymous SNPs in CLL4 trial patients for the identification of genetic variants influencing prognosis. Blood. 2008;111(3):1625–1633. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-110130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pfeifer D, Pantic M, Skatulla I, et al. Genome-wide analysis of DNA copy number changes and LOH in CLL using high-density SNP arrays. Blood. 2007;109(3):1202–1210. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-034256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gunn SR, Mohammed MS, Gorre ME, et al. Whole-genome scanning by array comparative genomic hybridization as a clinical tool for risk assessment in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J. Mol. Diagn. 2008;10(5):442–451. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2008.080033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kay NE, Eckel-Passow JE, Braggio E, et al. Progressive but previously untreated CLL patients with greater array CGH complexity exhibit a less durable response to chemoimmunotherapy. Cancer Genet. Cytogenet. 2010;203(2):161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Van Den Neste E, Robin V, Francart J, et al. Chromosomal translocations independently predict treatment failure, treatment-free survival and overall survival in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients treated with cladribine. Leukemia. 2007;21(8):1715–1722. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gunnarsson R, Mansouri L, Isaksson A, et al. Array-based genomic screening at diagnosis and during follow-up in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Haematologica. 2011;96(8):1161–1169. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2010.039768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Braggio E, Kay NE, Vanwier S, et al. Longitudinal genome-wide analysis of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia reveals complex evolution of clonal architecture at disease progression and at the time of relapse. Leukemia. 2012;26(7):1698–1701. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mian M, Rinaldi A, Mensah AA, et al. Large genomic aberrations detected by SNP array are independent prognosticators of a shorter time to first treatment in chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients with normal FISH. Ann. Oncol. 2013;24(5):1378–1384. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.O’Malley DP, Giudice C, Chang AS, et al. Comparison of array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) to FISH and cytogenetics in prognostic evaluation of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Int. J. Lab. Hematol. 2011;33(3):238–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-553X.2010.01284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gunn SR, Hibbard MK, Ismail SH, et al. Atypical 11q deletions identified by array CGH may be missed by FISH panels for prognostic markers in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2009;23(5):1011–1017. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hagenkord JM, Monzon FA, Kash SF, Lilleberg S, Xie Q, Kant JA. Array-based karyotyping for prognostic assessment in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: performance comparison of affymetrix 10K2.0, 250K Nsp, and SNP6.0 arrays. J. Mol. Diagn. 2010;12(2):184–196. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2010.090118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sherry ST, Ward MH, Kholodov M, et al. dbSNP: the NCBI database of genetic variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29(1):308–311. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.International Hapmap C The International HapMap Project. Nature. 2003;426(6968):789–796. doi: 10.1038/nature02168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Iafrate AJ, Feuk L, Rivera MN, et al. Detection of large-scale variation in the human genome. Nat. Genet. 2004;36(9):949–951. doi: 10.1038/ng1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lappalainen I, Lopez J, Skipper L, et al. DbVar and DGVa: public archives for genomic structural variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(Database issue):D936–D941. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Metzker ML. Sequencing technologies – the next generation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2010;11(1):31–46. doi: 10.1038/nrg2626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gargis AS, Kalman L, Berry MW, et al. Assuring the quality of next-generation sequencing in clinical laboratory practice. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012;30(11):1033–1036. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Clark MJ, Chen R, Lam HY, et al. Performance comparison of exome DNA sequencing technologies. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29(10):908–914. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bamshad MJ, Ng SB, Bigham AW, et al. Exome sequencing as a tool for Mendelian disease gene discovery. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011;12(11):745–755. doi: 10.1038/nrg3031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gibson G. Rare and common variants: twenty arguments. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011;13(2):135–145. doi: 10.1038/nrg3118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ansorge WJ. Next-generation DNA sequencing techniques. New Biotechnol. 2009;25(4):195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fabbri G, Rasi S, Rossi D, et al. Analysis of the chronic lymphocytic leukemia coding genome: role of NOTCH1 mutational activation. J. Exp. Med. 2011;208(7):1389–1401. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wang L, Lawrence MS, Wan Y, et al. SF3B1 and other novel cancer genes in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;365(26):2497–2506. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109016. [■■ Sequenced three CLL genomes and 88 whole exomes, and detected known recurrent mutations in CLL, including mutations in TP53 and novel mutations such as SF3B1.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mansouri L, Cahill N, Gunnarsson R, et al. NOTCH1 and SF3B1 mutations can be added to the hierarchical prognostic classification in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2013;27(2):512–514. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Landau DA, Carter SL, Stojanov P, et al. Evolution and impact of subclonal mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cell. 2013;152(4):714–726. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.019. [■■ Studies the intratumoral heterogeneity and clonal evolution in 149 CLL cases by using whole-exome sequencing technology.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ellisen LW, Bird J, West DC, et al. TAN-1, the human homolog of the Drosophila notch gene, is broken by chromosomal translocations in T lymphoblastic neoplasms. Cell. 1991;66(4):649–661. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90111-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rossi D, Rasi S, Fabbri G, et al. Mutations of NOTCH1 are an independent predictor of survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2012;119(2):521–529. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-379966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rossi D, Rasi S, Spina V, et al. Integrated mutational and cytogenetic analysis identifies new prognostic subgroups in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2013;121(8):1403–1412. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-09-458265. [■■ Proposes a new hierarchical model for predicting survival in CLL patients; this included novel mutations of NOTCH1, SF3B1 and BIRC3.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lopez C, Delgado J, Costa D, et al. Different distribution of NOTCH1 mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia with isolated trisomy 12 or associated with other chromosomal alterations. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2012;51(9):881–889. doi: 10.1002/gcc.21972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Quesada V, Conde L, Villamor N, et al. Exome sequencing identifies recurrent mutations of the splicing factor SF3B1 gene in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Nat. Genet. 2012;44(1):47–52. doi: 10.1038/ng.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rosati E, Sabatini R, Rampino G, et al. Constitutively activated Notch signaling is involved in survival and apoptosis resistance of B-CLL cells. Blood. 2009;113(4):856–865. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-139725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Fatima K, Paracha RZ, Qadri I. Post-transcriptional silencing of Notch2 mRNA in chronic lymphocytic [corrected] leukemic cells of B-CLL patients. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2012;39(5):5059–5067. doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-1301-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Oscier DG, Rose-Zerilli MJ, Winkelmann N, et al. The clinical significance of NOTCH1 and SF3B1 mutations in the UK LRF CLL4 trial. Blood. 2013;121(3):468–475. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-429282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Villamor N, Conde L, Martinez-Trillos A, et al. NOTCH1 mutations identify a genetic subgroup of chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients with high risk of transformation and poor outcome. Leukemia. 2013;27(5):1100–1106. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Fabbri M, Urani C, Sacco MG, Procaccianti C, Gribaldo L. Whole genome analysis and microRNAs regulation in HepG2 cells exposed to cadmium. Altex. 2012;29(2):173–182. doi: 10.14573/altex.2012.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Sportoletti P, Baldoni S, Cavalli L, et al. NOTCH1 PEST domain mutation is an adverse prognostic factor in B-CLL. Br. J. Haematol. 2010;151(4):404–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Shedden K, Li Y, Ouillette P, Malek SN. Characteristics of chronic lymphocytic leukemia with somatically acquired mutations in NOTCH1 exon 34. Leukemia. 2012;26(5):1108–1110. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Del Giudice I, Rossi D, Chiaretti S, et al. NOTCH1 mutations in +12 chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) confer an unfavorable prognosis, induce a distinctive transcriptional profiling and refine the intermediate prognosis of +12 CLL. Haematologica. 2012;97(3):437–441. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.060129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Stilgenbauer SBR, Schnaiter Andrea, Paschka P, et al. Gene mutations and treatment outcome in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: results from the CLL8 trial; 53rd Annual Meeting and Exposition of the American Society of Hematology; Atlanta, GA, USA. 10-13 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Rosati E, Sabatini R, De Falco F, et al. gamma-Secretase inhibitor I induces apoptosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells by proteasome inhibition, endoplasmic reticulum stress increase and notch down-regulation. Int. J. Cancer. 2013;132(8):1940–1953. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Visconte V, Makishima H, Jankowska A, et al. SF3B1, a splicing factor is frequently mutated in refractory anemia with ring sideroblasts. Leukemia. 2012;26(3):542–545. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Schwaederle M, Ghia E, Rassenti LZ, et al. Subclonal evolution involving SF3B1 mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2013;27(5):1214–1217. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Papaemmanuil E, Cazzola M, Boultwood J, et al. Somatic SF3B1 mutation in myelodysplasia with ring sideroblasts. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;365(15):1384–1395. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Rossi D, Fangazio M, Rasi S, et al. Disruption of BIRC3 associates with fludarabine chemorefractoriness in TP53 wild-type chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2012;119(12):2854–2862. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-12-395673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Zenz T, Gribben JG, Hallek M, Dohner H, Keating MJ, Stilgenbauer S. Risk categories and refractory CLL in the era of chemoimmunotherapy. Blood. 2012;119(18):4101–4107. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-312421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Stilgenbauer S, Liebisch P, James MR, et al. Molecular cytogenetic delineation of a novel critical genomic region in chromosome bands 11q22.3-923.1 in lymphoproliferative disorders. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93(21):11837–11841. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kanduri M, Tobin G, Aleskog A, Nilsson K, Rosenquist R. The novel NF-kappaB inhibitor IMD-0354 induces apoptosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood Cancer J. 2011;1(3):e12. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2011.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Hertlein E, Wagner AJ, Jones J, et al. 17-DMAG targets the nuclear factor-kappaB family of proteins to induce apoptosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: clinical implications of HSP90 inhibition. Blood. 2010;116(1):45–53. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-263756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ding L, Ley TJ, Larson DE, et al. Clonal evolution in relapsed acute myeloid leukaemia revealed by whole-genome sequencing. Nature. 2012;481(7382):506–510. doi: 10.1038/nature10738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Keats JJ, Chesi M, Egan JB, et al. Clonal competition with alternating dominance in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2012;120(5):1067–1076. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-01-405985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Walter MJ, Shen D, Ding L, et al. Clonal architecture of secondary acute myeloid leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366(12):1090–1098. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1106968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Mamanova L, Coffey AJ, Scott CE, et al. Target-enrichment strategies for next-generation sequencing. Nat. Methods. 2010;7(2):111–118. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Domenech E, Gomez-Lopez G, Gzlez-Pena D, et al. New mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia identified by target enrichment and deep sequencing. PloS ONE. 2012;7(6):e38158. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Woyach JA, Johnson AJ, Byrd JC. The B-cell receptor signaling pathway as a therapeutic target in CLL. Blood. 2012;120(6):1175–1184. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-02-362624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Websites

- 201.Nexus copy number – Biodiscovery. www.biodiscovery.com

- 202.Ensembl Genome Browser. www.ensembl.org