Abstract

Background

Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC), mainly causing infantile diarrhoea, represents one of at least six different categories of diarrheagenic E. coli with corresponding distinct pathogenic schemes. The mechanism of EPEC pathogenesis is based on the ability to introduce the attaching-and-effacing (A/E) lesions and intimate adherence of bacteria to the intestinal epithelium. The role and the epidemiology of non-traditional enteropathogenic E. coli serogroup strains are not well established. E. coli O157:H45 EPEC strains, however, are described in association with enterocolitis and sporadic diarrhea in human. Moreover, a large outbreak associated with E. coli O157:H45 EPEC was reported in Japan in 1998. During a previous study on the prevalence of E. coli O157 in healthy cattle in Switzerland, E. coli O157:H45 strains originating from 6 fattening cattle and 5 cows were isolated. In this study, phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of these strains are described. Various virulence factors (stx, eae, ehxA, astA, EAF plasmid, bfp) of different categories of pathogenic E. coli were screened by different PCR systems. Moreover, the capability of the strains to adhere to cells was tested on tissue culture cells.

Results

All 11 sorbitol-positive E. coli O157:H45 strains tested negative for the Shiga toxin genes (stx), but were positive for eae and were therefore considered as EPEC. All strains harbored eae subtype α1. The gene encoding the heat-stable enterotoxin 1 (EAST1) was found in 10 of the 11 strains. None of the strains, however, carried ehx A genes. The capability of the strains to adhere to cells was shown by 10 strains harbouring bfp gene by localized adherence pattern on HEp-2 and Caco-2 cells.

Conclusion

This study reports the first isolation of typical O157:H45 EPEC strains from cattle. Furthermore, our findings emphasize the fact that E. coli with the O157 antigen are not always STEC but may belong to other pathotypes. Cattle seem also to be a reservoir of O157:H45 EPEC strains, which are described in association with human diseases. Therefore, these strains appear to play a role as food borne pathogens and have to be considered and evaluated in view of food safety aspects.

Background

Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC), mainly causing infantile diarrhoea, represents one of the at least six different categories of diarrheagenic E. coli with corresponding distinct pathogenic schemes [1]. Most of the EPEC strains belong to a series of O antigenic groups known as EPEC O serogroups: O26, O55, O86, O111, O114, O119, O125, O126, O127, O128, O142 and O158.

The main mechanism of EPEC pathogenesis is the ability to introduce attaching-and-effacing (A/E) lesions on intestinal cells characterized by microvillus destruction, intimate adherence of strains to the intestinal epithelium, pedestal formation and aggregation of polarized actin at sites of bacterial attachment [2].

The genetic determinants for the production of A/E lesions are located on the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE), a pathogenicity island that contains the genes encoding intimin (eae), a type III secretion system, a number of secreted proteins (ESP) and the translocated intimin receptor (Tir) [2]. Characterization of eae genes revealed the existence of different eae variants. At present, 15 (α1, α2, β1, β2, γ1, γ2/θ, δ/κ, ε, ζ, η, ι, λ, μ, ν, ξ) genetic variants of the eae gene have been identified [3-7]. It is discussed that different intimins may be responsible for different host- and tissue cell tropism [8,9]. In epithelial culture cells EPEC strains produce characteristic adherence patterns: (i) localized adherence (LA), where microcolonies attach after 3 hours incubation to one or two small areas on the cells [10,11]; (ii) diffuse adherence (DA), where bacteria cover the cells uniformly [10]; (iii) enteroadherent-aggregative adherence (AA), where the bacteria have a characteristic stacked-brick-like arrangement [12] and (iiii) localized adherence-like adherence (LAL), characterized by formation of less-compact microcolonies or clusters of bacteria than those by LA [13]. Localized adherence is associated with the presence of the large EPEC adherence factor (EAF) plasmid, on which also the cluster of genes encoding bundle-forming pili (BFP) is present [1]. EPEC are classified as typical, when possessing the EAF plasmid; whereas atypical EPEC strains do not possess the EAF plasmid [14,15].

Typical and atypical EPEC strains usually belong to certain serotype clusters, differ in their adherence patterns on cultured epithelial cells (typical: LA; atypical: DA; AA; LAL), are typically found in different hosts (typical EPEC strains have only been recovered from humans), and display difference in their intimin types [15].

The role and the epidemiology of non-traditional enteropathogenic E. coli serogroup strains in human diarrhea are not well established. E. coli O157:H8 and E. coli O157:H45 EPEC strains have been described to be associated with diarrhea in human [4,16]. Makino et al. [17] reported the first large outbreak with E. coli O157:H45 EPEC in Japan in 1998. Nevertheless, these O157 EPEC strains are not well characterized.

This study reports the first isolation of O157:H45 EPEC strains from cattle and phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of the isolated strains are described.

Results and discussion

All 11 sorbitol-positive E. coli O157:H45 strains, six strains isolated from fattening cattle and five strains isolated from cows tested negative for Shiga toxin genes (stx). The eae gene, which is strongly correlated to the attaching-and-effacing lesions, was present in all strains. Therefore, these strains are considered to be EPEC. Our findings emphasize the fact that E. coli with the O157 O antigen are not always STEC but may belong to other pathotypes. Further results of strain characterization are shown in Tab. 2.

Table 2.

Characterization results of 11 sorbitol-fermenting O157:H45 EPEC strains isolated from cattle in Switzerland

| No. of strains | LEE in selC | Intimin type | EAF Plasmid | bfp | Adherence pattern | astA | ehx |

| 9 | yes | α1 | + | + | LA | + | - |

| 1 | yes | α1 | - | + | LA | + | - |

| 1 | yes | α1 | - | - | NA | - | - |

LA: localized adherence; NA: no adherence

In all tested strains, LEE was inserted in selC and thus these strains could be evolutionarily more akin to the EPEC 1 and EHEC 1 clones than to other clones [18]. Further characterization of the eae variants showed in all strains eae subtype α1. Oswald et al. [4] testing in their study the distribution of intimin types among different EPEC strains, found the same eae subtype in O157:H45 strains isolated from human with diarrhea.

The gene encoding the heat-stable enterotoxin (EAST1), representing an additional determinant in the pathogenesis of E. coli diarrhea, was found in ten of the 11 strains. None of the strains, however, carried ehxA genes.

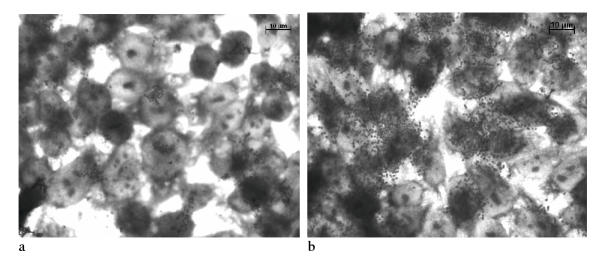

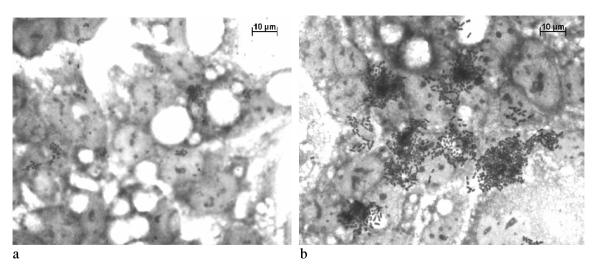

Nine strains were positive for the EAF plasmid and 10 strains harbored the bfpA gene encoding bundlin, the structural subunit of the bundle-forming pilus expressed by typical EPEC strains. The EAF plasmid negative but bfpA positive strain may have a defect in the EAF region that does not interfere with the plasmid's function. All bfpA gene positive strains showed a localized adherence (LA) pattern, the penotpyical characteristic associated with the expression of bundle-forming pili and therefore seem to be a typical EPEC. For HEp-2 and Caco-2 cells similar results were obtained (Figure 1, 2). Caco-2 cells instead of Hela cells were used for adhesion assay and FAS test, because they represent a system close to the human intestinal cells. Furthermore, Vieira et al. [19] have shown that results obtained by Caco-2 cells are comparable to Hela cells.

Figure 1.

Localized adherence (LA) pattern of the E. coli O157:H45 strain 1070/03 on HEp-2 cells. (a) 3 h assay, (b) 6 h assay

Figure 2.

Localized adherence (LA) pattern of the E. coli O157:H45 strain 1070/03 on Caco-2 cells. (a) 3 h assay, (b) 6 h assay

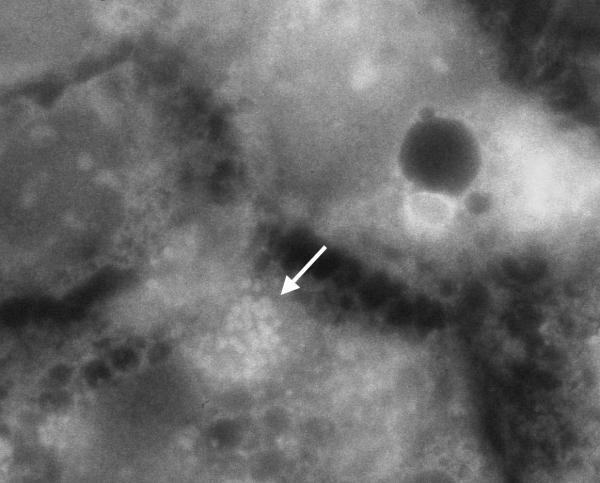

10 of the 11 strains showed an A/E property with the fluorescent actin staining (FAS) test (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Actin fluorescence micrograph showing E. coli O157:H45 strain 1070/03-infected Caco-2 cells

According to Kaper [14] most of our O157:H45 strains have to be classified as typical EPEC strains, because they are possessing the EAF plasmid and are showing the localized adherence (LA) pattern. However, they are harboring astA genes, which is more common for atypical EPEC strains [15].

Further studies are needed to evaluate the role of such EPEC strains isolated from asymptomatic animals.

Conclusions

Cattle have not only to be considered as important asymptomatic carriers of O157 STEC but can also be a reservoir of O157 EPEC strains, which are described in association with human diseases. These strains appear to play a role as food borne pathogens and have to be considered in view of food safety aspects.

Methods

Origin of the E. coli strains

The strains characterized in this work were isolated during a recent study on prevalence of E. coli O157 in healthy cattle in Switzerland [20]. The study was based on investigations that were carried out within the last one and a half years (January 2002 – June 2003) in two EU-approved slaughterhouses. From 2,930 bovine fecal samples (1,183 calves, 1,201 fattening cattle and 546 cows), 11 sorbitol-fermenting E. coli O157:H45 strains (from 6 fattening cattle and 5 cows) were isolated. The determination of the O and H antigens was performed as previously described using all available O (O1 to O181) and H (H1 to H56) antisera [6].

Genotypic characterization of the O157:H45 strains

PCR for the detection of putative virulence genes were performed in a T3 thermocycler (Biometra, Germany). PCR reagents were purchased from PROMEGA (Madison, Wis.) and primers were synthesized by MICROSYNTH (Balgach, Switzerland). The 50-μl PCR mixtures normally consisted of 2 μl of bacterial suspension in 42 μl of double-distilled water, 5 μl of 10-fold-concentrated polymerase synthesis buffer containing 2.0 mM MgCl2, 200 μM (each) desoxynucleosid triphosphate (dNTP), 30 pmol of each primer and 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase. The PCR primers, target sequences and product sizes are listed in Table 1. Differences in the normal PCR mixture and cycling conditions for each PCR were previously described in the cited literature.

Table 1.

Sequences and predicted lengths of PCR amplification products of oligonucleotide primers used

| Target | Primer | Oligonucleotide sequence (5'-3')Sequence | Product size | Reference |

| stx | VT1 | ATTGAGCAAAATAATTTATAT GTG | 523 bp | 21 |

| VT2 | TGATGATGGCAATTCAGTAT | 520 bp | ||

| eae | SK1 | CCCGAATTCCGCACAAGCATAAGC | 863 bp | 22 |

| SK2 | CCCGGATCCGTCTCGCCAGTATTCG | |||

| eae-α1 | EAE-FB | AAAACCGCGGAGATGACTTC | 820 bp | 7 |

| EAE-A | CACTCTTCGCATCTTGAGCT | |||

| eae-α2 | IH2498aF | AGACCTTAGGTACATTAAGTAAGC | 517 bp | 7 |

| IH2498aR | TCCTGAGAAGAGGGTAATC | |||

| eae-β1 | EA-B1-F | CGCCACTTAATGCCAGCG | 811 bp | 7 |

| EAE-B | CTTGATACACCTGATGACTGT | |||

| eae-β2 | EA-B2-F | CCCGCCACTTAATCGCACGT | 807 bp | 7 |

| EAE-B | CTTGATACACCTGATGACTGT | |||

| eae-γ1 | EAE-FB | AAAACCGCGGAGATGACTTC | 804 bp | 7 |

| EAE-C1 | AGAACGCTGCTCACTAGATGTC | |||

| eae-γ2/θ | EAE-FB | AAAACCGCGGAGATGACTTC | 808 bp | 7 |

| EAE-C2 | CTGATATTTTATCAGCTTCA | |||

| eae-δ/κ | EAE-FB | AAAACCGCGGAGATGACTTC | 833 bp | 7 |

| EAE-D | CTTGATACACCCGATGGTAAC | |||

| eae-ε | EAE-FB | AAAACCGCGGAGATGACTTC | 722 bp | 7 |

| LP5 | AGCTCACTCGTAGATGACGGCAAGCG | |||

| eae-ζ | Z1 | GGTAAGCCGTTATCTGCC | 206 bp | 7 |

| Z2 | ATAGCAAGTGGGGTGAAG | |||

| eae-η | EAE-FB | AAAACCGCGGAGATGACTTC | 712 bp | 7 |

| LP8 | TAGATGACGGTAAGCGAC | |||

| eae-ι | EAE-FB | AAAACCGCGGAGATGACTTC | 807 bp | 7 |

| LP7 | TTTATCCTGCTCCGTTTGCT | |||

| eae-λ | 68.4F | CGGTCAGCCTGTGAAGGGC | 466 bp | 7 |

| 68.4R | ATAGATGCCTCTTCCGGTATT | |||

| eae-μ | FV373F | CAACGGTAAGTCTCAGACAC | 443 bp | 7 |

| FV373R | CATAATAAGCTTTTTGGCCTACC | |||

| eae-ν | IH1229aF | CACAGCTTACAATTGATAACA | 311 bp | 7 |

| IH1229aR | CTCACTATAAGTCATACGACT | |||

| eae-ξ | EAE-FB | AAAACCGCGGAGATGACTTC | 468 bp | 7 |

| B49R | ACCACCTTTAGCAGTCAATTTG | |||

| ehxA | HlyA1 | GGTGCAGCAGAAAAAGTTGTAG | 1551 bp | 23 |

| HlyA2 | TCTCGCCTGATAGTGTTTGGTA | |||

| astA | EAST1 | CCA TCA ACA CAG TAT ATC CGA | 111 bp | 24 |

| EAST2 | GGT CGC GAG TGA CGG CTT TGT | |||

| EAF | EAF1 | CAG GGT AAA AGA AAG ATG ATA A | 397 bp | 25 |

| EAF25 | TAT GGG GAC CAT GTA TTA TCA | |||

| bfpA | EP1 | AAT GGT GCT TGC GCT TGC TGC | 326 bp | 26 |

| EP2 | GCC GCT TTA TCC AAC CTG GTA |

To verify whether LEE was inserted downstream of the selC locus, PCR reactions that amplify the junctions of this locus with the E. coli chromosome were performed according to Sperandio et al. [27]. Primers K255 (5'-GGTTGAGTCGATTGATCTCTGG-3') and K260 (5'-GAGCGAATATTCCGATATCTGGTT-3') were used for the right junction; K296 (5'-CATTCTGAAACAAACTGCTC-3') and K295 (5'-CGCCGATTTTTCTTAGCCCA-3') for the left junction, and K261 (5'-CCTGCAAATAAACACGGCGCAT-3') and K260 for the intact selC gene.

Adhesion assay and FAS test

E. coli colonies were characterized by the pattern of adherence to HEp-2 and Caco-2 cells as described by Karch et al. [28] with minor modifications. Briefly, HEp-2 and Caco-2 cells were grown for 48 h with 5% CO2 on sterilized coverslips (13 mm diameter; Bibby Sterilin™ Ltd., Stone, England) in 24-well flat-bottom tissue culture plates with low evaporation lid (16 mm diameter; BD Falcon™, Bedford, USA) containing Minimum essential medium (MEM with Earle's salts, 25 mM HEPES, without L-Glutamine;GIBCO™ Invitrogen AG, Basel, Switzerland) supplemented with fetal calf serum (FCS, 10%, Bio Concept™, Allschwil, Switzerland), MEM Non Essential Amino Acids (MEM NEAA (100x) without L-Glutamine, GIBCO™ Invitrogen AG, Basel, Switzerland) and GlutaMAX™I Supplement 200 mM (100x), (GIBCO™ Invitrogen AG, Basel, Switzerland). Bacteria used for the adhesion assay were grown over night in LB-broth Miller (Becton Dickinson, Maryland, USA). Prior to incubation, the confluent cells were washed two times with Dulbecco's phospate buffered saline (D-PBS (1x) without Calcium and Magnesium, GIBCO™ Invitrogen AG, Basel, Switzerland). E. coli diluted 1:100 in 1 ml fresh media (MEM with supplements) was added to the cells and was incubated for 3 h at 37°C and 5% CO2. After this incubation period, monolayers were washed five times with D-PBS (3 h assay) or monolayers were washed ten times with D-PBS, fresh media (MEM with supplements) was added and an additional incubation period of 3 h proceeded (6h assay). Subsequently, the monolayers were washed five times with D-PBS and the cells were fixed for 10 min with 4 Methanol. After the staining with May-Grünwald-Giemsa (Fluka™, Buchs SG, Switzerland), the coverslips were examined by light microscopy to determine the adherence patterns of the strains.

The following fluorescent actin-staining (FAS) test was performed on Caco-2 cells according to Karch et al. [28] with minor modifications. The cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde in D-PBS, then washed three times with D-PBS and incubated for 5 min with 0.1% Triton X-100 (Fluka™, Buchs SG, Switzerland) in D-PBS. After another three washes with D-PBS, the monolayers were incubated with 5 μg/ml of fluorescein isothiocyanate labelled phaloidin (Sigma, Steinheim, Germany) for 30 min. After another three washes with D-PBS, the coverslips were examined by fluorescence microscopy (Leica ™).

Authors' contributions

RS isolated the strains and drafted the manuscript, CZ was responsible for further strain characterization, NB performed adhesion assays and FAS tests, MB performed the PCR typing of eae genes and JE has done serotyping of the strains. All authors read, commented on and approved of the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Sandra Schumacher and Carmen Kaiser for her excellent technical assistance. This study was partly supported by a grant from the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (FIS G03/025-COLIRED-O157).

Contributor Information

Roger Stephan, Email: stephanr@fsafety.unizh.ch.

Nicole Borel, Email: n.borel@access.unizh.ch.

Claudio Zweifel, Email: zweifelc@fsafety.unizh.ch.

Miguel Blanco, Email: mba@lugo.usc.es.

Jesús E Blanco, Email: jeba@lugo.usc.es.

References

- Nataro JP, Kaper JB. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:142–201. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.1.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke G, Phillips AD, Rosenshine I, Dougan G, Kaper JB, Knutton S. Enteropathogenic and enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli: more subversive elements. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:911–921. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adu-Bobie J, Frankel G, Bain C, Goncalves AG, Trabulsi LR, Douce G, Knutton S, Dougan G. Detection of intimins alpha, beta, gamma, and delta, four intimin derivatives expressed by attaching and effacing microbial pathogens. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:662–668. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.3.662-668.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald E, Schmidt H, Morabito S, Karch H, Marches O, Caprioli A. Typing of intimin genes in human and animal enterohemorrhagic and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli: characterization of a new intimin variant. Infect Immun. 2000;68:64–71. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.1.64-71.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang WL, Kohler B, Oswald E, Beutin L, Karch H, Morabito S, Caprioli A, Suerbaum S, Schmidt H. Genetic diversity of intimin genes of attaching and effacing Escherichia coli strains. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:4486–4492. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.12.4486-4492.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco M, Blanco JE, Mora A, Rey J, Alonso JM, Hermoso M, Hermoso J, Alonso MP, Dahbi G, González EA, Bernárdez MI, Blanco J. Serotypes, virulence genes and intimin types of Shiga toxin (Verotoxin)-producing Escherichia coli isolates from healthy sheep in Spain. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:1351–1356. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.4.1351-1356.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco M, Blanco JE, Mora A, Dahbi G, Alonso MP, González EA, Bernárdez MI, Blanco J. Serotypes, virulence genes and intimin types of Shiga toxin (Verotoxin)-producing Escherichia coli isolates from cattle in Spain: identification of a new intimin variant gene (eae-xi) J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:645–651. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.2.645-651.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jores J, Zehmke K, Eichberg J, Rumer L, Wieler LH. Description of a novel intimin variant (type zeta) in the bovine O84:NM verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli strain 537/89 and the diagnostic value of intimin typing. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2003;228:370–376. doi: 10.1177/153537020322800407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piérard D, Muyldermans G, Moriau L, Stevens D, Lauwers S. Identification of new verocytotoxin type 2 variant B-subunit genes in human and animal Escherichia coli isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3317–3322. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.11.3317-3322.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaletsky IC, Silva ML, Trabulsi LR. Distinctive patterns of adherence of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli to HeLa cells. Infect Immun. 1984;45:534–536. doi: 10.1128/iai.45.2.534-536.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutton S, Shaw RK, Anantha RP, Donnenberg MS, Zorgani AA. The type IV bundle-forming pilus of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli undergoes dramatic alterations in structure associated with bacterial adherence, aggregation and dispersal. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:499–509. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nataro JP, Kaper JB, Robins-Browne R, Prado V, Vial P, Levine MM. Patterns of adherence of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli to HEp-2 cells. Paediatr Infect Dis J. 1987;6:829–831. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198709000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaletsky IC, Pelayo JS, Giraldi R, Rodrigues J, Pedroso MZ, Trabulsi LR. EPEC adherence to Hep-2 cells. Rev Microbiol. 1996;27:58–62. [Google Scholar]

- Kaper JB. Defining EPEC. Rev Microbiol. 1996;27:130–133. [Google Scholar]

- Trabulsi LR, Keller R, Tardelli Gomes TA. Typical and atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:508–513. doi: 10.3201/eid0805.010385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scotland SM, Willshaw GA, Cheasty T, Rowe B. Strains of Escherichia coli O157:H8 from human diarrhea belong to attaching and effacing class of E. coli. J Clin Pathol. 1992;45:1075–1078. doi: 10.1136/jcp.45.12.1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino S, Asakura H, Shirahata T, Ikeda T, Takeshi K, Arai K, Nagasawa M, Abe T, Sadamoto T. Molecular epidemiological study of a mass outbreak caused by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli O157:H45. Microbiol Immunol. 1999;43:381–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1999.tb02419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieler LH, McDaniel TK, Whittam TS, Kaper JB. Insertion site of the locus of enterocyte effacement in enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli differs in relation to the clonal phylogeny of the strains. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;156:49–53. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(97)00403-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira M, Andrale J, Trabulsi L, Rosa A, Dias A, Ramos S, Frankel G, Gomes TA. Phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of Escherichia coli strains of non-enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) serogroups that carry eae and lack the EPEC adherence factor and Shiga toxin DNA probe sequences. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:762–772. doi: 10.1086/318821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Saigh H, Zweifel C, Blanco J, Blanco JE, Blanco M, Usera MA, Stephan R. Fecal shedding of Escherichia coli O157, Salmonella spp. and Campylobacter spp. in Swiss cattle at slaughter. J Food Protect. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Burnens AP, Frey A, Lior H, Nicolet J. Prevalence and clinical significance of vero-cytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli (VTEC) isolated from cattle in herds with and without calf diarrhoea. Zentralbl Veterinarmed B. 1995;42:311–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0450.1995.tb00715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt H, Plaschke B, Franke S, Rüssmann H, Schwarzkopf A, Heesemann J, Karch H. Differentiation in virulence patterns of Escherichia coli possessing eae-genes. Med Microbiol Immunol. 1994;183:23–31. doi: 10.1007/BF00193628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt H, Beutin L, Karch H. Molecular analysis of the plasmid-encoded hemolysin of Escherichia coli O157:H7 strain EDL 933. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1055–1061. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.3.1055-1061.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T, Nakazawa M. Detection and sequences of the enteroaggregative Escherichia coli heat-stable enterotoxin 1 gene in enterotoxigenic E. coli strains isolated from piglets and calves with diarrhea. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:223–227. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.1.223-227.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke J, Granke S, Schmidt H, Schwarzkopf A, Wieler LH, Baljer G, Beutin L, Karch H. Nucledtide sequence analysis of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) adherence factor probe and development of PCRfor rapid detection of EPEC harbouring virulence plasmids. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2460–2463. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.10.2460-2463.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunzburg ST, Tornieporth NG, Riley LW. Identification of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli by PCR-based detection of the bundle-forming pilus gene. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1375–1377. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.5.1375-1377.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperandio V, Kaper JB, Bortolini MR, Nevez BC, Keller R, Trabulsi LR. Characterization of the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) in different enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) and shigatoxin producing Escherichia coli (STEC) serotypes. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;164:133–139. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(98)00205-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karch H, Böhm H, Schmidt H, Gunzer F, Aleksic S, Heesemann J. Clonal structure and pathogenicity of shiga-like toxin-producing, sorbitol-fermenting Escherichia coli O157:H- J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1200–1205. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.5.1200-1205.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]