Abstract

Objectives

Among persons in current HIV outpatient care, data on opioid prescribing are lacking. This study aims to evaluate predictors of repeat opioid prescribing and to characterize outpatient opioid prescribing practices.

Methods

Retrospective cross-sectional study of persons ≥ 18 years in HIV outpatient care who completed an annual behavioral assessment between June 2008 and June 2009. Persons were grouped by ≤ 1 and ≥ 2 opioid prescriptions (no-repeat-opioid and repeat-opioids, respectively). Independent predictors for repeat-opioids were evaluated. Opioid prescribing practices were characterized in a sub-study of persons prescribed any opioid.

Results

Overall, 659 persons were included, median age 43 years, 70% men, and 68% African American. Independent predictors of repeat-opioids (88 [13%] persons) included opportunistic illnesses (both current and previous), depression, peripheral neuropathy, and hepatitis C coinfection (P < 0.05). In the subgroup, 140 persons received any opioid prescription (96% short-acting, 33% tramadol). Indications for opioid prescribing were obtained in 101 (72%) persons, with 97% for noncancer-related pain symptoms. Therapeutic response was documented on follow-up in 67 (48%) persons, with no subjective relief of symptoms in 63%. Urine drug screens were requested in 6 (4%) persons, and all performed were positive for illicit drugs.

Conclusions

Advanced HIV disease and greater medical and neuropsychiatric comorbidity predict repeat opioid prescribing, and these findings reflect the underlying complexities in managing pain symptoms in this population. We also highlight multiple deficiencies in opioid prescribing practices and nonadherence to guidelines, which are of concern as effective and safe pain management for our HIV-infected population is an optimal goal.

Introduction

Opioid prescribing is common among persons in the HIV outpatient clinic setting,1 especially with increased use of opioids for noncancer pain.2–6 Repeat opioid prescribing may be a marker of adverse psychosocial factors, advanced HIV disease, and substance use in persons who require more intensive outpatient follow-up.1 Current data are, however, limited in HIV-infected persons. Specifically, data illustrating a relationship between opioid prescribing and higher-risk sexual behaviors, prevalent sexually transmitted infections (STI), and neuropsychological comorbidity such as cognitive impairment and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are lacking. Accordingly, we performed a comprehensive examination of predictors of repeat opioid prescribing in a group of mixed sex and race persons in HIV outpatient care. We hypothesized that those prescribed opioids repeatedly would have more adverse psychosocial circumstances, advanced HIV disease, greater comorbidity, and more higher-risk sexual behaviors than counterparts not prescribed opioids repeatedly. Lastly, as data on opioid prescribing practices in the outpatient HIV-infected population are also lacking, we evaluated data on indications for opioid prescribing, type of opioid regimens prescribed, therapeutic response, use of urine drug screens, and other specialist referral in a sub-study of persons in receipt of any opioid prescription.

Methods

Subjects

This was a retrospective cross-sectional study of a convenience sample of persons ≥ 18 years engaged in HIV outpatient care who had completed an annual behavioral assessment and attended ≥ 2 clinic appointments between June 2008 and June 2009. To determine predictors of repeat opioid prescribing, persons were grouped into repeat-opioids (≥ 2 opioid prescriptions during that time) and no-repeat-opioids (≤ 1 opioid prescription during that time), respectively. Local Human Studies Protection Office approval was obtained, and all patient identifiers were removed after data analysis.

Setting

Washington University School of Medicine HIV outpatient clinics based in St. Louis city comprises 9 half-day sessions a week supervised by 12 infectious diseases specialists with a mean of 17 years (range 6 to 45) of clinical experience.

Predictors of Opioid Prescribing Data Collection and Definitions

Sociodemographic, clinical, HIV, current medication (combination antiretroviral therapy [cART], antidepressants, nonopioid analgesia, and neuromodulating [adjuvant analgesics]), plus most recent CD4+ count, HIV RNA, and bacterial STI testing data were collected from clinic charts of every person who fulfilled the above inclusion criteria. The annual behavioral assessment contained questions on education, housing, annual income, employment, recent sexual activity (reports of anal/vaginal sexual intercourse in the last 3 months), recent condom use (reports of condom use during recent sexual activity), and alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drug use. Measures of cognitive function, depression and symptoms of PTSD were also assessed. An International HIV Dementia Scale score of ≤ 10 (range 0 to 12) defined cognitive impairment.7 Depression severity was assessed by the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9).8 Depressive symptoms were defined by PHQ-9 scores ≥ 1. A PTSD Check List score of ≥ 10 defined PTSD.9 The use of ≥ 3 antiretroviral drugs from ≥ 2 different classes defined cART. Viral suppression was HIV RNA < 50 copies/mL. Opportunistic illnesses (OI) were defined as standard.10 Comorbidity was ≥ 1 comorbid condition. Comorbid conditions included cardiovascular disease (hypertension, coronary artery disease, congestive cardiac failure, and cerebrovascular disease), diabetes mellitus, psychiatric disorders (depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia), chronic viral hepatitis, chronic renal failure, and peripheral neuropathy. Homeless was not currently having either owned or rented property. Alcohol intake was the usual weekly number of alcoholic drinks consumed among persons who had drunk alcohol in the last 12 months. Recent cocaine or marijuana use was ≤ 7 days from the time of the annual behavioral assessment. Complete bacterial STI testing included results of urine DNA amplification for Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis and rapid plasma reagin (RPR). Treponema pallidum antibody (TPA) was performed for the confirmation of newly reactive RPRs. Re-exposure was a 4-fold increase in RPR in a previously treated person. A positive STI result was a finding of any of the above.

Opioid Prescribing Practices Sub-Study

We examined opioid prescribing practices in a sub-study of persons mentioned earlier who were in receipt of any opioid prescription without exclusion. Persons were further divided into single-opioid and repeat-opioids groups (1 opioid prescription and ≥ 2 opioid prescriptions, respectively).

Sub-Study Data Collection and Definitions

Opioid prescribing practices related to the first opioid prescribed in the study period (index opioid). The type and number of days of index opioid prescribed were obtained from each person's medication list after review of all past and present medications. The prescriber (HIV care provider vs. other provider) was also noted, as was documentation of the indication for the index opioid. Indications (cancer pain, pain not related to cancer, cough suppression, heroin withdrawal, and other) for index opioid prescribing were either formally documented in the management plan, undocumented but apparent to NÖ from the clinic charts, or unknown (unclear or not documented). All additional opioid prescriptions during the study period were noted, as were the frequency of prescriptions (days). Other data included documentation of therapeutic response at the next clinic visit, aberrant drug-related behaviors and index opioid adverse effects, performance of urine drug screens at or during time of index opioid prescribing and their results, and referral to another specialist clinic.

Pain severity scores were rarely documented to quantify the severity of pain for which the opioid was prescribed and therapeutic response in those cases was defined as patient subjective report of improvement or resolution of symptoms without actual pain severity score quantification. Conversely, no therapeutic response at the next clinic visit was defined as report of ongoing symptoms without subjective improvement or resolution.

Receipt of nonopioid analgesia (acetaminophen, high-dose aspirin, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs]) and neuromodulating medications (eg, amitryptiline, gabapentin, and pregabalin) at the time of index opioid prescribing were noted. Opioids were any drug that contained buprenorphine, butorphenol, propoxyphene, tramadol, hydrocodone, codeine, oxycodone, hydromorphone, methadone, fentanyl, or morphine. Tramadol, a synthetic analog of codeine, which binds to the mu-opioid receptor and inhibits neuronal reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine,11 was included as it has been classified as a controlled substance under the Military Pain Care Act of 2008, in Kentucky (December 2008) and Arkansas (July 2007) and in Canada and Sweden. Long-acting opioids were methadone and extended/sustained/controlled release preparations of oxycodone, oxymorphone, fentanyl, and morphine. All other opioids were considered short-acting. Aberrant drug-related behaviors included reports of lost or stolen opioid prescriptions/medications, opioid diversion, opioid abuse, or illicit drug use.

Statistical Analyses

Significant predictors of repeat-opioids vs. no-repeat-opioids were compared between groups. Separate analyses were performed to examine differences in opioid prescribing practices in the sub-study between single-opioid and repeat-opioids groups. Chi-square tests were used for categorical variables, and Student's t-test and Mann–Whitney U test, for normally and non-normally distributed continuous variables, respectively. All P values were 2 tailed and considered significant at P < 0.05. Multivariate logistic regression models were developed in a stepwise fashion, including all variables with P < 0.10 in the univariate analyses apart from recent condom use and HIV RNA on cART. The final model included all variables with P < 0.05 in the multivariable model. The C statistic (area under the receiver-operating characteristic) curve was used to assess the model's discriminatory ability, and the Hosmer–Lemeshow test was used to assess the model's calibration (goodness of fit). HIV RNA values were log10 transformed for analysis. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 18.0 (Chicago, IL, U.S.A.).

Results

Overall, 659 persons were included in the study and grouped as follows: 88 (13%) repeat-opioids and 571 (87%) no-repeat-opioids. Table 1 details their characteristics. As hypothesized, repeat-opioids predicted greater adverse characteristics than no-repeat-opioids in terms of older age (45 vs. 42 years, respectively), low annual income, unemployment, current tobacco use and presence of depressive symptoms, PTSD, comorbidity, cardiovascular disease, psychiatric illness, chronic hepatitis C coinfection, and peripheral neuropathy (all P < 0.05). Repeat-opioids also predicted more years since HIV diagnosis (9 vs. 8 years), both previous and current OI, and lower CD4+ T cell counts (all P < 0.05). Despite comparable use of cART and proportion with viral suppression, repeat-opioids predicted higher mean levels HIV RNA on cART (2.38 vs. 2.12 log10 copies/mL) (P < 0.001). This also remained the case when considering all persons regardless of current cART use (2.80 log10 copies/mL repeat-opioids vs. 2.57 log10 copies/mL no-repeat-opioids) (P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Summary of socio-demographic, clinical and HIV characteristics according to opioid use among persons who had completed the annual behavioral assessment.

| Characteristics | All persons (n=666) | Any-opioid (n=147) | No-opioid (n=519) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)a | 43 (32-49) | 45 (39-51) | 41 (31-49) | <0.001 |

| Male sex | 465 (70%) | 105 (71%) | 360 (69%) | 0.63 |

| Race | 0.89 | |||

| African American | 456 (69%) | 104 (71%) | 352 (68%) | - |

| Caucasian | 175 (26%) | 38 (26%) | 137 (26%) | - |

| Other* | 35 (6%) | 5 (3%) | 30 (6%) | - |

| High school education or more | 360 (54%) | 80 (54%) | 280 (54%) | 0.97 |

| >$10,000 income in last year | 302 (45%) | 53 (36%) | 249 (48%) | 0.01 |

| Employed full or part time | 366 (55%) | 59 (40%) | 307 (59%) | <0.001 |

| Own housing | 492 (74%) | 110 (75%) | 382 (74%) | 0.77 |

| Recent sexual activity (n=659) | 289 (44%) | 61 (45%) | 228 (44%) | 0.57 |

| Recent condom use, (%) (n=285) | 79% | 74% | 82% | 0.17 |

| Positive STI result (n=548 complete) | 41(7%) | 8 (6%) | 33 (8%) | 0.60 |

| Current tobacco use | 310 (47%) | 87 (59%) | 223 (43%) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol consumption/week (units)b | 4 (2-10) | 3 (2-8) | 4 (2-10) | 0.19 |

| Recent marijuana use | 137 (21%) | 40 (28%) | 97 (19%) | 0.03 |

| Depression scorea (n=641) | 5 (1-10) | 6 (3-14) | 5 (1-9) | 0.003 |

| Minimal depression or worse | 528 (79%) | 121 (82%) | 407 (78%) | 0.002 |

| In receipt of an antidepressant | 182 (27%) | 43 (29%) | 139 (27%) | 0.55 |

| Cognitive score a (n=609) | 11 (10-12) | 11 (9-12) | 11 (10-12) | 0.69 |

| Cognitive impairment present | 248 (31%) | 60 (41%) | 188 (31%) | 0.09 |

| PTSD scorea (n=647) | 0 (0-10) | 5 (0-15) | 0 (0-10) | <0.001 |

| PTSD present | 208 (31%) | 66 (45%) | 142 (27%) | <0.001 |

| Anxiety score a (n=647) | 4 (1-10) | 6 (3-13) | 3 (1-8) | <0.001 |

| Mild anxiety or worse | 162 (24%) | 54 (37%) | 108 (21%) | <0.001 |

| Comorbidity present | 485 (73%) | 120 (82%) | 365 (70%) | <0.001 |

| Malignancy | 47 (7%) | 22 (15%) | 25 (5%) | <0.001 |

| Active malignancy (%) | 10 (2%) | 6 (4%) | 4 (1%) | 0.004 |

| Years since HIV diagnosisa | 8 (3-13) | 9 (5-14) | 8 (3-13) | 0.01 |

| Previous OI | 195 (29%) | 57 (39%) | 138 (27%) | 0.004 |

| Current OI | 21 (3%) | 10 (7%) | 11 (2%) | 0.004 |

| ART naïve | 64 (10%) | 11 (8%) | 53 (10%) | 0.32 |

| In receipt of cART | 504 (76%) | 111 (76%) | 393 (76%) | 0.96 |

| % viral suppression on cART | 71% | 66% | 73% | 0.15 |

| Log10 viral load (copies/mL) | 2.16±.0.05 | 2.36±.0.11 | 2.10±.0.05 | 0.02 |

| CD4+ (cells/mm3)a | 406 (217-614) | 318 (142-585) | 416 (234-620) | 0.01 |

| % <200 cells/mm3 | 22% | 31 % | 20 % | 0.003 |

| % ≥ 350 cells/mm3 | 57 % | 47% | 60 % | 0.004 |

Mean ±. standard error of mean

Median (interquartile range).

Hispanic, bi- or mulit-racial, Asian American, American Indian, other,.STI=sexually transmitted infection. OI=opportunistic infection, cART= combination active antiretroviral therapy

Among recently sexually active persons, reports of no recent condom use were higher among repeat-opioids (32% vs. 18%). Overall, however, there were fewer positive STI results (1% vs. 8%) in this group (both P < 0.05).

No differences were found in terms of sex, race, education, housing, recent sexual activity, weekly alcohol intake, receipt of antidepressants, ART experience, recent marijuana or cocaine use (21% and 2%, respectively, overall), history of illicit drug use (50% of 434 persons who answered in total) or presence of cognitive impairment, chronic renal failure, diabetes mellitus, hepatitis B coinfection, and malignancy.

Independent predictors of repeat-opioids in multivariate analysis included current OI (aOR, 6.46; 95% CI, 2.01 to 20.73, P = 0.002), depressive symptoms (aOR, 4.27; 95% CI, 1.25 to 14.71, P = 0.02), presence of peripheral neuropathy (aOR, 3.64; 95% CI, 1.80 to 7.36, P < 0.001), previous OI (aOR, 2.54; 95% CI, 1.40 to 4.60, P = 0.002), and hepatitis C coinfection (aOR, 2.47; 95% CI 1.12 to 5.44, P = 0.02). The C statistic for the derivation model was 0.73, indicating good discrimination, and the Homser–Lemeshow test showed good calibration (χ2 = 2.2; P = 0.71).

Opioid Prescribing Practices

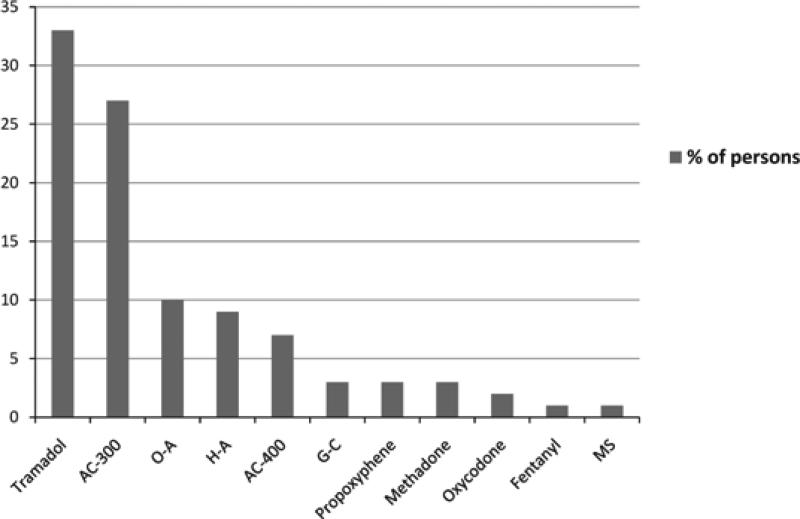

Table 2 details opioid prescribing characteristics for 140 persons prescribed any opioid (63% repeat-opioids and 37% single-opioid) between June 2008 and June 2009. Overall, 71% of index opioids were prescribed by HIV care providers, 96% short-acting and 33% tramadol (Figure 1). Single-opioid groups were more likely to be prescribed acetaminophen–codeine 400 (OR 6.67, 95% CI 1.33 to 33.3), acetaminophen–codeine 300 (OR 2.22, 95% CI 1.04 to 4.76), and guaifenesin–codeine (OR 2.86, 95% CI 2.28 to 3.57). Repeat-opioids were more likely to be prescribed hydrocodone–acetaminophen (OR 1.69, 95% CI 1.47 to 1.96), oxycodone (OR 1.67, 95% CI 1.45 to 1.89), and oxycodone–acetaminophen (OR 1.72 (95% CI 1.47 to 2.00). Repeat-opioids were prescribed the index opioid for a longer duration (30 vs. 22 days single-opioid, P = 0.02). Indications for index opioid prescribing were formally documented (80, 57%), undocumented but apparent (21, 15%), or unknown (39, 28%). Among the former 101 persons with formally documented or apparent indications for index opioid prescribing, almost all were given for noncancer pain symptoms: 57% for musculoskeletal, 17% for neurological, 7% visceral, 8% postoperative, 3% dermatological, 2% dental, and 1% otolaryngological. Additional indications included cough, influenza-like illness symptoms, and heroin withdrawal (1% each). Table 3 details the most common pain indications for the index opioid. Postoperative pain (OR 14.2, 95% CI 1.82 to 100, P < 0.001) and noncancer pain (OR 2.96, 95% CI 2.25 to 3.92), respectively, predicted single-opioid. Therapeutic response was documented in only 67 persons, with no relief of symptoms reported in 63% of those persons. Thirty-two persons were in receipt of nonopioid analgesia at the time of index opioid prescribing, 56% NSAIDs and 47% neuromodulating medications (predominantly gabapentin). Of 6 urine drug screens requested, all were in repeat-opioids (P = 0.05), and all of those performed contained illicit drugs. Only one urine drug screen was performed prior to consideration of a repeat opioid prescription, which was then subsequently not given. The remaining 4 urine drug screens were requested and performed after the opioid prescription was given, and all persons subsequently received further opioid prescriptions regardless of this previous result. Twenty-five persons were referred to another specialty clinic for their pain issues: 14 attended, 2 were already seeing another specialist, and the remainder did not attend either because of patient refusal (3), financial constraints (1), specialist clinic refusal to see the patient (2), and unknown reasons (3). Repeat-opioids predicted referral (OR 5.44, 95% CI 1.54 to 19.23). There was no documentation of opioid adverse effects, and aberrant drug-related behaviors were only documented for a few persons.

Table 2.

Characterization of opioid prescribing practices and associations with repeat-opioids

| Characteristics | All Persons (n = 140) | Repeat-opioids (n = 88) | Single-opioid (n = 52) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prescriber | 0.29 | |||

| HIV care provider | 99 (71%) | 65 (74%) | 34 (65%) | - |

| Other provider | 41 (29%) | 23 (26%) | 18 (35%) | - |

| Short-acting opioid | 134 (96%) | 84 (95%) | 50 (96%) | 0.84 |

| Duration of prescription (days)* | 30 (11-30) | 30 (14-30) | 22 (9-30) | 0.02 |

| Opioid prescribing indication available | 101 (72%) | 65 (74%) | 36 (69%) | 0.56 |

| Non-cancer pain | 98 (97%) | 65 (100%) | 33 (92%) | 0.02 |

| In receipt of adjuvant analgesic | 32 (23%) | 24 (27%) | 8 (15%) | 0.11 |

| Therapeutic response documented | 67 (48%) | 47 (53%) | 20 (38%) | 0.09 |

| No relief of symptoms, (%) | 63 | 66 | 55 | 0.40 |

| Urine drug screen requested | 6 (4%) | 6 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 0.05 |

| Urine drug screen performed | 5 (83%) | 5 (83%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Illicit drugs present, (%) | 100 | 100 | 0 | - |

| Referral to other specialist† | 25 (18%) | 22 (25%) | 3 (6%) | 0.004 |

Median (interquartile range).

Pain clinic (6), orthopedics (4), neurology (4), physiotherapy (3), already seeing a specialist (3), dentist (1), pain clinic/orthopedics (1), neurosurgeons (1), ophthalmology (1), and rheumatology (1).

Figure 1.

Number of Patients Prescribed Drug by Type of Drug

Table 3.

Details of the most common types of pain symptoms for which the index opioid was prescribed

| Type of Pain | Symptom | Number (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Musculoskeletal (n = 58) | Low back pain | 17 (29) |

| Lower limb/joint pain | 11 (19) | |

| Upper limb/joint pain | 11 (19) | |

| Avascular necrosis of the hips | 8 (13) | |

| Others (general, chest pain, neck pain) | 11 (19) | |

| Neurological (n = 17) | Peripheral neuropathy | 12 (70) |

| Headaches/migraines | 3 (18) | |

| Others (spinal cord problems, sciatica) | 2 (12) | |

| Visceral (n = 7) | Abdominal pain | 5 (71) |

| Genitourinary | 1 (14) | |

| Oral candidiasis | 1 (14) | |

| Postoperative (n = 8) | Orthopedic | 4 (50) |

| Others (cardiothoracic, colorectal, otolaryngological) | 4 (50) | |

| Dermatological (n = 3) | Others (severe psoriasis, trauma, herpes zoster) | 3 (100) |

Among the repeat-opioids group, there were a median of 3 (1 to 7) opioid prescriptions every 53 (30 to 120) days. Forty-nine (55%) persons were prescribed the same opioid repeatedly, and tramadol was the most common opioid repeatedly prescribed. Guaifenesin–codeine and longer-acting opioids, other than methadone, were never repeatedly prescribed. Among those who received different opioids, 1% had a short-acting opioid changed to a longer-acting opioid, and this occurred at the time of the third repeat prescription. As per the medication list, 7 (8%) persons were prescribed opioids by multiple different providers (HIV and other providers). No mention of this was made in the corresponding clinic notes from the HIV care provider.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study of a diverse group of persons engaged in contemporary HIV-related outpatient care, we demonstrated that repeat opioid prescribing is common and that it predicts multiple adverse characteristics. Furthermore, we demonstrated that opioid prescribing practices are lacking in terms of documentation of indication for the opioid prescription, rare use of objective pain severity scores, and both limited documentation of therapeutic efficacy and low rates of actual subjective therapeutic response. Furthermore, urine drug screens were underutilized and aberrant drug-related behaviors rarely reported. This is the first study, to our knowledge, to characterize predictors of repeat opioid prescribing and examine opioid prescribing practices in such a population. Overall, 13% of our study population was prescribed opioids repeatedly, and this predicted OI (past and current), depressive symptoms, hepatitis C coinfection, and peripheral neuropathy diagnoses compared to persons not prescribed opioids repeatedly. Our findings mirror those reported among a predominantly Caucasian male outpatient HIV-infected population, of whom 14% were on long-term opioids. Associations with long-term opioid use included an AIDS diagnosis, in addition to public or no insurance, history of injection drug use (IDU), use of anxiolytics and neuromodulators, a history of abuse, and more frequent clinic follow-up.1 Opioid prescribing is triggered by reporting of pain symptoms, which are conversely associated with a complex interplay of adverse socioeconomic factors, advanced HIV-related immunodeficiency (including AIDS diagnoses), medical comorbidities, and neuropsychiatric issues as we demonstrated in our study.12–22 AIDS diagnoses are also associated with poverty and significant psychological distress,23,24 which may heighten pain perception and reporting of pain symptoms.13,15,25 Conversely, pain may be an expression of stress and depression among populations that are not typically asked about their psychological health.26 Chronic pain is common among persons with hepatitis C infection,27,28 who often have an IDU history and psychiatric and psychosocial comorbidity.29 Hepatitis C infection and advanced HIV disease are also both associated with painful distal, symmetrical sensory polyneuropathies,20,30 which can significantly impact quality of life and may require opioid use, in addition to first-line neuromodulating agents, for treatment.31

Our finding on univariate analysis of significantly lower CD4+ T cell counts in the repeat-opioids group raises concern regarding opioid-induced lymphopenia.6,32,33 Lower CD4+ T cell counts in this group may have also been because of higher levels of HIV viremia and in turn highlight the potential impact of opioid-enhanced HIV replication. Morphine stimulation of mu receptors has been shown to upregulate expression of CXCR4 and CCR5 co-receptors on CD3 lymphocytes and CD14 monocytes, facilitating HIV infection and viral replication.34,35 Further study of the potential adverse clinical impact of opioid prescription and use on CD4+ T cell counts and HIV viral replication is warranted.

Among persons prescribed opioids, we found a deficiency in documentation of indications for opioid prescribing, a clear lack of use of pain severity scores and limited follow-up regarding therapeutic efficacy (in terms of documentation and objective follow-up of symptoms). These findings do not comply with a consensus statement on the use of opioids in pain treatment which states that “documentation is essential for supporting the evaluation, the reasons for opioid prescribing, the overall pain management treatment plan, any consultations received, and periodic review of the status of the patient”.2 However, lack of documentation could in part be explained by other clinic providers prescribing almost one-quarter of opioids to our clinic population. Regardless, it is contingent upon the HIV care provider to be comprehensively aware of their patient's current medications to provide comprehensive care, prevent drug–drug interactions, and reduce multi-provider prescribing of opioids, as was the case for a proportion of our clinic population.4,36

Among persons with a documented subjective therapeutic response, we found a high number who reported no relief of symptoms. Routine utilization of pain severity scores would provide better objective measurements of therapeutic response to opioids prescribed and augment the pain management plan.2 Our finding of repeated prescribing of short-acting opioids without conversion to longer-acting opioids supports previous reports of underappreciation and undertreatment of pain issues in HIV-infected persons.4,13,19 HIV care providers often find treatment of pain to be limited by time constraints37 and may not be well versed in pain management, appropriate opioid prescribing practices, or the impact of drug–drug interactions with antiretrovirals.3,4,36,38 This can significantly impact quality of life and employment, cause unnecessary distress, and increase utilization of outpatient clinics and emergency departments.2,3,13,20,22,39,40 Overall, our data highlight the complex interrelated factors underlying opioid prescribing and illustrate the need for a multifaceted approach to the HIV-infected person reporting pain12,21 with use of integrated services for the optimal management of pain symptoms.1,2,4,13,36,38

Fears of opioid misuse, opioid diversion, opiate overdose, or of ongoing illicit drug use may also hinder aggressive use of opioids by HIV care providers.2,37 These fears can, however, be erroneous.41 Urine drug screens could objectively identify those at risk for substance abuse and opioid misuse; however, they were underutilized in our clinic and did not appear to alter opioid prescribing practices even when positive. Opioid treatment agreements have also been found to decrease opioid misuse and increase provider confidence and control in prescribing opioids.37,42 This study was conducted during a period when there was no formal clinic-based chronic pain management policy; however, this has now been introduced (use of opioid renewal contracts, use of urine drug screens, and utilization of pain severity scores among others), and data from this study have been presented to our clinic providers. We will subsequently re-evaluate our opioid prescribing practices in the future. Use of abuse-deterrent opioid formulations may also increase provider confidence in prescribing opioids.43

Referral to pain and nonpain specialist clinics for treatment of pain symptoms or their underlying cause, respectively, can also be considered in the management of pain symptoms. In our clinic, this was mainly done for persons prescribed opioids repeatedly, and this would seem appropriate as HIV care providers should be able to manage standard pain issues. It is contentious, however, whether specialist referral is beneficial for the HIV-infected person complaining of pain. Nonpain specialists may not globally assess the pain nor provide the broader approach to pain management that is often required.37 However, our data argue that we are not providing optimal pain management for a number of our clinic population and that referral to pain specialist clinics may be warranted unless we improve our clinical practice.

There are limitations to this study. This was a retrospective study of opioid prescribing but nonetheless used data that had been prospectively collected from a large number of persons who had completed the annual behavioral assessment. We only documented opioid prescribing and never confirmed whether these prescriptions were actually filled. Persons with low annual income may not have been able to fill their prescription furthering their pain and associated distress. We may have also misclassified persons into the no-repeat-opioid or single-opioid groups if they received opioid prescriptions from another provider outside our clinical system (database) or outside the study time period. STI results were incomplete. Finally, our review of opioid prescribing practices was limited to a single site and may not be reflective of other institutions.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that persons in current HIV-related outpatient care are commonly prescribed opioids repeatedly and that this group represents a vulnerable population with more advanced HIV disease and greater medical and neuropsychiatric comorbidity. We also highlight multiple deficiencies in opioid prescribing practices and nonadherence to guidelines, which may or may not be reflective of other similar institutions providing outpatient HIV-related care. Such findings are of concern as effective and safe pain management for our HIV-infected population is an optimal goal.

Acknowledgement

This publication was partially supported by Grant Number UL1 RR024992, specifically KL2RR024994 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH. ETO has received research grants from Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, Gilead, Abbott, Tibotec, and Boehinger Ingelheim through Washington University, served as a consultant for Tibotec and GlaxoSmithKline, and served on speakers’ bureau or received honoraria from Merck, Tibotec, GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Monogram Sciences, and Gilead. EPB has stock options for The Natural Standard, and TT received a Bristol-Myers Squibb Virology Fellow's Grant in 2009.

References

- 1.Koeppe J, Armon C, Lyda K, Nielsen C, Johnson S. Ongoing pain despite aggressive opioid management among persons with HIV. Clin J Pain. 2010;26:190–198. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181b91624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Academy of Pain Medicine and the American Pain Society The use of opioids for the treatment of chronic pain. A consensus statement from the American Academy of Pain Medicine and the American Pain Society. Clin J Pain. 1997;13:6–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Argoff CE, Silversheen DI. A comparison of long and short-acting opioids for the treatment of chronic noncancer pain: tailoring therapy to meet patient needs. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:602–612. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)60749-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Basu S, Bruce RD, Barry DT, Altice FL. Pharmacological pain control for human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults with a history of drug dependence. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007;32:399–409. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chou R. Clinical guidelines from the American Pain Society and the American Academy of Pain Medicine on the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2009;119:469–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ballantyne JC, Mao J. Opioid therapy for chronic pain. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1943–1953. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra025411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sacktor NC, Wong M, Nakasujja N, et al. The International HIV dementia scale: a new rapid screening test for HIV dementia. AIDS. 2005;19:1367–1374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, Forneris CA. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL). Behav Res Ther. 1996;34:669–673. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castro KG, Ward JW, Slutsker L, et al. 1993 revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. MMWR. 1992;41:RR–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reeves RR, Burke RS. Tramadol: basic pharmacology and emerging concepts. Drugs Today (Barc). 2008;44:827–836. doi: 10.1358/dot.2008.44.11.1289441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richardson JL, Heikes B, Karim R, Weber K, Anastos K, Young M. Experience of pain among women with HIV disease. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23:503–511. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harding R, Lampe FC, Norwood S, et al. Symptoms are highly prevalent among HIV outpatients and associated with poor adherence and unprotected sexual intercourse. Sex Transm Infect. 2010;86:520–524. doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.038505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nair SN, Mary TR, Prarthana S, Harrison P. Prevalence of pain in patients with HIV/AIDS: a cross-sectional survey in a South Indian State. Indian J Palliat Care. 2009;15:67–70. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.53550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stone AA, Krueger AB, Steptoe A, Harter JK. The socioeconomic gradient in daily colds and influenza, headaches, and pain. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:570–572. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singer EJ, Zorilla C, Fahy-Chandon B, Chi S, Syndulko K, Tourtellotte WW. Painful symptoms reported by ambulatory HIV-infected men in a longitudinal study. Pain. 1993;54:15–19. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beesdo K, Hoyer J, Jacobi F, Low NC, Höfler M, Wittchen HU. Association between generalized anxiety levels and pain in a community sample: evidence for diagnostic specificity. J Anxiety Disord. 2009;23:684–693. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hooten WM, Townsend CO, Bruce BK, Warner DO. The effects of smoking status on opioid tapering among patients with chronic pain. Anesth Analg. 2009;108:308–315. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31818c7b99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larue F, Fontaine A, Colleau SM. Underestimation and undertreatment of pain in HIV disease: multicentre study. BMJ. 1997;314:23–28. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7073.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ellis RJ, Rosario D, Clifford DB, et al. CHARTER Study Group Continued high prevalence and adverse clinical impact of human immunodeficiency virus-associated sensory neuropathy in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy: the CHARTER Study. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:552–558. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsao JC, Stein JA, Dobalian A. Pain, problem drug use history, and aberrant analgesic use behaviors in persons living with HIV. Pain. 2007;15:133. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Breitbart W, McDonald MV, Rosenfeld B, et al. Pain in ambulatory AIDS patients. I: pain characteristics and medical correlates. Pain. 1996;68:315–321. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(96)03215-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karon JM, Fleming PL, Steketee RW, De Cock KM. HIV in the United States at the turn of the century: an epidemic in transition. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1060–1068. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.7.1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vogl D, Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W, et al. Symptom prevalence, characteristics, and distress in AIDS outpatients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999;18:253–262. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(99)00066-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mao J, Gold MS, Backonja M. Combination drug therapy for chronic pain: a call for more clinical studies. J Pain. 2011;12:157–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shacham E, Basta TB, Reece M. Symptoms of psychological distress among African Americans seeking HIV-related mental health care. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008;22:413–421. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silberbogen AK, Janke EA, Hebenstreit C. A closer look at pain and hepatitis C: preliminary data from a veteran population. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2007;44:231–244. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2006.05.0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morasco BJ, Huckans M, Loftis JM, et al. Predictors of pain intensity and pain functioning in patients with the hepatitis C virus. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32:413–418. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenblum A, Joseph H, Fong C, Kipnis S, Cleland C, Portenoy RK. Prevalence and characteristics of chronic pain among chemically dependent patients in methadone maintenance and residential treatment facilities. JAMA. 2003;289:2370–2378. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.18.2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Acharya JN, Pacheco VH. Neurologic complications of hepatitis C. Neurologist. 2008;14:151–156. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0b013e31815fa594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dworkin RH, O'Connor AB, Audette J, et al. Recommendations for the pharmacological management of neuropathic pain: an overview and literature update. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(suppl):S3–S14. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2009.0649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quang-Cantagrel ND, Wallace MS, Ashar N, Mathews C. Long-term methadone treatment: effect on CD4+ lymphocyte counts and HIV-1 plasma RNA level in patients with HIV infection. Eur J Pain. 2001;5:415–420. doi: 10.1053/eujp.2001.0262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Donahoe RM, Vlahov D. Opiates as potential cofactors in progression of HIV-1 infections to AIDS. J Neuroimmunol. 1998;15:83. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(97)00224-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steele AD, Henderson EE, Rogers TJ. Mu-opioid modulation of HIV-1 coreceptor expression and HIV-1 replication. Virology. 2003;309:99–107. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Finley MJ, Happel CM, Kaminsky DE, Rogers TE. Opioid and nociceptin receptors regulate cytokine and cytokine receptor expression. Cell Immunol. 2008;252:146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2007.09.00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lehmann KA. Opioids: overview on action, interaction and toxicity. Support Care Cancer. 1997;5:439–444. doi: 10.1007/s005200050111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wiedemer NL, Harden PS, Arndt IO, Gallagher RM. The opioid renewal clinic: a primary care, managed approach to opioid therapy in chronic pain patients at risk for substance abuse. Pain Med. 2008;8:573–584. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Palliative Care. World Health Organisation [6 October 2010];2005 Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/topics/palliative/PalliativeCare/en/

- 39.Dobalian A, Tsao JC, Duncan RP. Pain and the use of outpatient services among persons with HIV: results from a nationally representative survey. Med Care. 2004;42:129–138. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000108744.45327.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Josephs JS, Fleishman JA, Korthuis PT, Moore RD, Gebo KA. HIV Research Network. Emergency department utilization among HIV-infected patients in a multisite, multistate study. HIV Med. 2010;11:74–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2009.00748.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vijayaraghavan M, Penko J, Guzman D, Miaskowski C, Kushel MB. Primary care providers’ judgments of opioid analgesic misuse in a community-based cohort of HIV-infected indigent adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:412–418. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1555-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Starrels JL, Becker WC, Alford DP, Kapoor A, Williams AR, Turner BJ. Systematic review: treatment agreements and urine drug testing to reduce opioid misuse in patients with chronic pain. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:712–720. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-11-201006010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schneider JP, Matthews M, Jamison RN. Abuse-deterrent and tamper-resistant opioid formulations: what is their role in addressing prescription opioid abuse? CNS Drugs. 2010;24:805–810. doi: 10.2165/11584260-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]