Abstract

Despite enormous efforts, biochemical and molecular mechanisms associated with equine reproduction, particularly processes of pregnancy establishment, have not been well characterized. Previously, PCR-selected suppression subtraction hybridization analysis was executed to identify unique molecules functioning in the equine endometrium during periods of pregnancy establishment, and granzyme B (GZMB) cDNA was found in the pregnant endometrial cDNA library. Because GZMB is produced from natural killer (NK) cells, endometrial expression of GZMB and immune-related transcripts were characterized in this study. The level of GZMB mRNA is higher in the pregnant endometrium than in non-pregnant ones. This expression was also confirmed through Western blot and immunohistochemical analyses. IL-2 mRNA declined as pregnancy progressed, while IL-15, IFNG and TGFB1 transcripts increased on day 19 and/or 25. Analyses of IL-4 and IL-12 mRNAs demonstrated the increase in these transcripts as pregnancy progressed. Increase in CCR5 and CCR4 mRNAs indicated that both Th1 and Th2 cells coexisted in the day 25 pregnant endometrium. Taken together, the endometrial expression of immune-related transcripts suggests that immunological responses are present even before the trophectoderm actually attaches to the uterine epithelial cells.

Keywords: Endometrium, Equine, Granzyme B (GZMB), Implantation

The horse is possibly the oldest and certainly the noblest domestic animal, comprised of various breeds with differing phenotypic characteristics [1]. Several features of pregnancy establishment in the mare (the female horse) and other equids are unusual and differ markedly from equivalent events in other, well-studied large domestic animal species [2, 3]. In domestic animals such as cows and sows, hatched blastocysts play a role in the prevention of maternal corpus luteum demise, the process called the maternal recognition of pregnancy. It is thought that biochemical and possibly physical communications resulting from expanded blastocysts and the uterine endometrium are required if a pregnancy is to succeed in ruminant and porcine species. In the mare, the blastocyst does not elongate and rather actively migrates within the uterine body and horns, and this trans-uterine migration of the embryonic vesicle is thought to play a key role in this physiologic event [2, 3]. However, it is still not clear what happens between the embryo and maternal endometrium at the time of implantation during early pregnancy.

In addition to biochemical and physical communications thus far characterized, the proper maternal immune response to the fetus is also required for successful implantation. To find genes that have not been studied, PCR-selected suppression subtraction hybridization analysis was previously carried out [4]. From such an analysis, granzyme B (GZMB) was found numerous times in the day 13 pregnant endometrial cDNA library. Because this is a member of granzymes and produced by NK cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) [5, 6], this gene expression could be used as a marker for determining the activity of uterine NK (uNK) cells possibly involved in pregnancy establishment. Uterine NK cells can produce cytokines such as IFNG, GM-CSF, IL-10, TGFB and IL-8 [7,8,9,10]. These uNK-derived cytokines may have significant effects on decidualization and trophoblast invasion [11] and may be an important part of vascular remodeling during placental development. Many different cytokines that alter NK cell function have been shown to be present in the human endometrium [12, 13].

The endometrium is a source of both IL-15 and PRL [11, 14, 15], and both of these cytokines have been implicated in the proliferation and differentiation of uNK cells. In humans, IL-15 is present throughout the menstrual cycle and is increased during the secretory phase and early pregnancy [11, 16,17,18]. It has been suggested that IL-15 expression in the endometrium may be important for NK cell attachment, and perhaps IL-15 expression by the decidual endometrium may be involved in specific localization of uNK cells close to spiral arteries [18]. In addition, several reports have demonstrated effects of TGFB on NK cells [19,20,21,22,23]. Members of the TGFB family are powerful immunoregulatory molecules that act on a range of different immune cells and can demonstrate both activating and inhibitory function [24,25,26,27]. It has been shown that endogenous TGFB-mediated inhibition is a mechanism that regulates uNK cell-derived cytokine production [10].

It was proposed decades ago that successful pregnancy is associated with T helper-2 (Th2) lymphocyte-type cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-10, rather than a T helper-1 (Th1) lymphocyte-type such as IL-2 and IFNG [28]. However, it has become clear that it is not so simple [13], and there is evidence that both Th1 and Th2 cytokines are produced in deciduas [17]. In fact, several reports suggest that moderate Th1-type cytokine stimulation might be essential for a pregnancy to succeed [29,30,31]. However, as excessive cytokine stimulation might induce implantation failure, regulatory cytokines and Th2-type cytokines might also be required to regulate the endometrial immune system [31].

In this study, we hypothesized that early embryonic mobility, intra-uterine migration, could elicit an endometrial immune-related response in the mare. Thus, it would be possible to identify maternal recognition factors by demonstrating the immunological mechanism during the implantation period. Based on this hypothesis, the objectives of this study were to examine endometrial GZMB and immune-related transcripts, and to illustrate the endometrial immune system possibly functioning during early pregnancy in the mare.

Materials and Methods

Animals and tissue collections

Clinically healthy Thoroughbred mares (n=8, 4–16 years) exhibiting regular estrous cycles were maintained at two local farms through arrangements made by the Japan Racing Association (JRA) and the Hidaka Horse Breeders' Association in Urakawa, Hokkaido, Japan. This study protocol was reviewed and approved by the animal care and ethics committees at the JRA and the University of Tokyo. Horses, allowed to graze together each day, were fed twice daily on a balanced ration of pelleted feed and hay. Ovaries of these horses were monitored by rectal palpation and ultrasonography (ECHOPAL, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) with a 5.0–7.5 MHz changeable probe (EUP-O33J) [32]. To synchronize estrous cycles, prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α, 0.25 mg/mare, Planate; Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Osaka, Japan) was injected intramuscularly during the luteal phase. Human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG, 2,500 IU/mare, GONATROPIN; ASKA Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan) was then administered to induce ovulation when growing follicles of over 3.5 cm in diameter were found. Six of the 8 mares were mated with fertile stallions at the appropriate timing, and pregnancy was confirmed with the presence of conceptus using ultrasonography.

Uteri were obtained from cyclic mares on day 13 and pregnant mares on days 13, 19 and 25 (n=2 mares/day) immediately following slaughter at a local abattoir. Uterine horns and body were examined, and each was divided into three parts [4, 33]. From each of the divided uterine horns and body, a piece of uterine tissue was excised and embedded in paraffin for immunohistochemistry studies [4]. Endometrial tissues from the remaining uteri were frozen immediately and stored at –70 C.

Suppression subtractive hybridization (SSH)

The subtractive libraries, in which transcripts in the day 13 cyclic endometrium were subtracted from those in the day 13 pregnant endometrium, were constructed using a PCR-select cDNA subtraction kit (BD Biosciences Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA) [4]. In brief, total RNA was extracted from frozen endometrial tissues using Isogen (Nippon Gene, Tokyo, Japan), and mRNA was obtained from total RNA using Oligotex-dT30 (Takara Bio Inc., Otsu, Shiga, Japan), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Double-stranded cDNA was synthesized and digested with RsaI. Two rounds of hybridization and PCR amplification were performed, and then the amplified products containing the subtracted cDNA were ligated into pGEM Easy-T Vector (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Plasmids were isolated from colonies of endometrial cDNA libraries and subjected to an automated sequence analysis using a 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Nucleotide sequence comparisons were performed using the BLAST network program (National Center for Biotechnology Information) [4, 33].

PCR and quantitative real-time PCR

In this study, frozen endometrial samples used were the uterine regions (uterine horn close the uterine body, ipsilateral to the corpus luteum) where the conceptus was found. Total RNA was extracted from these frozen endometrial tissues using Isogen (Nippon Gene), from which cDNA was synthesized using M-MLV reverse transcriptase according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). PCR analysis was performed essentially as described previously [4, 33, 34]. Real-time PCR was utilized to quantify targeted cDNAs using an ABI PRISM 7900HT system (Applied Biosystems) [4, 34]. Oligonucleotide primers were designed with the assistance of the web-based Primer3 software and are listed in Table 1. PCR reactions were carried out using Ex Taq Hot Start Version containing SYBR-Green I (Takara Bio Inc.), and levels of each target mRNA relative to ACTB mRNA were determined using the 2-ΔCT method. Levels of ACTB mRNA in various endometrial tissues were examined and found to be consistent throughout uterine horns in day 13, 19 and 25 cyclic and/or pregnant mares.

Table 1. Oligonucleotide primers for real-time PCR analyses.

| Name (GenBank accession No.) | Sequence | Product length (bp) |

| ACTB | F: 5'- cgacatccgtaaggacctgt -3' | |

| (NM_001081838) | R: 5'- gtggacaatgaggccagaat -3' | 192 |

| GZMB | F: 5'- tctgacagctgctc actgct -3' | |

| (NM_001081881) | R: 5'- cagtcagcttggcctttctc -3' | 188 |

| IL-2 | F: 5'- ccttgcaaacagtgcaccta -3' | |

| (NM_001085433) | R: 5'- gcatttcctccagaggtttg-3' | 221 |

| IL-4 | F: 5'- caaaacgctgaacaacctca -3' | |

| (NM_001082519) | R: 5'- ttgaggttcctgtccagtcc -3' | 198 |

| IL-12 | F: 5'- cacctggaccacctcagttt-3' | |

| (NM_001082511) | R: 5'- acggtgctgctcttgtcttt-3' | 203 |

| IL-15 | F: 5'- gaggctggcattcatgtctt -3' | |

| (AY682849) | R: 5'- cgtttctggactcatgcaaa-3' | 232 |

| IFNG | F: 5'- tcagagccaaatcgtctcct-3' | |

| (EU000434) | R: 5'- cgctggaccttcagatcatt-3' | 186 |

| TGFB1 | F: 5'- agttaagcgtggagcagcat -3' | |

| (AF175709) | R: 5'-ctggaactgaacccgttgat -3' | 244 |

| CCR4 (LOC100056549) | F: 5'- tagacaccaccgtggatgaa-3' | |

| (XM_001490244) | R: 5'- gaattcccaagcagaccaaa-3' | 154 |

| CCR5 | F: 5'- cagaaaaccgacgtgagaca -3' | |

| (NM_001091534) | R: 5'- gggagggtgagaaggaaaag-3' | 191 |

F, Forward; R, Reverse.

Western blotting analysis

Endometrial proteins were prepared by homogenizing the frozen endometrial tissues in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 1% SDS, 1 mM NaVO4, 50 mM NaF) supplemented with inhibitors, 1 mM DTT, 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 2 μg/ml aprotinin, 5 μg/ml leupeptin and 1 μg/ml Pepstatin A. Protein concentrations in these lysates were determined by the Bradford protein assay [4, 33].

Protein samples (10 μg) were denatured and separated by 15% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Immobilon; Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) [4, 33]. To reduce nonspecific binding, the membranes were treated with Block Ace (Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma) at room temperature for 1 h and were then incubated with mouse anti-equine GZMB antibody (1:200) [35] or mouse anti-ACTB antibody (30 ng/ml; Sigma) at 4 C for 12 h. After incubation, the membranes were washed four times in TBS-Tween 20, and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG or goat anti-mouse IgG (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA) at room temperature for 1 h. Signals were detected using ECL Plus Western Blotting Detection Reagents (GE Healthcare UK, Buckinghamshire, UK) [4, 33].

Immunohistochemistry

Endometrial tissues in paraffin were sectioned at 4 μm, and mounted onto MAS-coated slides (Matsunami Glass Ind., Osaka, Japan) [4,33]. Antigen retrieval was initially performed in sodium citrate buffer (0.01 M, pH 6.0), which was treated with heat (95 C for 5 min). To reduce endogenous peroxidase activity and quench nonspecific staining, the sections were treated in 3% H2O2/methanol at room temperature for 30 min and then in Block Ace at room temperature for 1 h. The slide sections were incubated with mouse anti-equine GZMB antibody (1:200) [35] or normal mouse IgG (2 μg/ml) at 4 C for 12 h, followed by incubation with biotin-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG (GE Healthcare UK) at room temperature for 1 h. Specific signals were visualized using the VECTASTAIN Elite ABC Kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). Tissue sections were then counterstained with hematoxylin.

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as means ± SEM. Measurements from real-time PCR analysis were subjected to one-way ANOVA using the general linear model procedures (STATISTICA; StatSoft, Tulsa, OK, USA) [4, 34]. The model used in the ANOVA included day and replicate as sources of variation. When a significant effect on day of pregnancy was detected (P<0.05), the data for mRNA amounts were analyzed by Duncan's multiple range tests.

Results

Identification of expressed genes in the pregnant endometrium

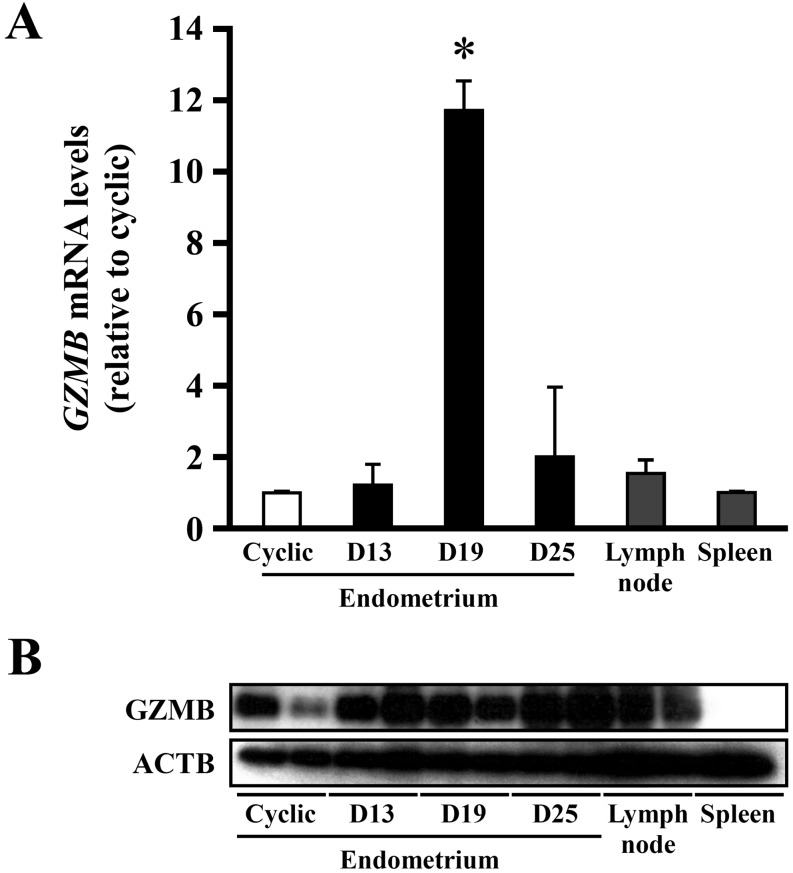

PCR-selected suppression subtraction hybridization was used to identify and clone mRNAs expressed in the pregnant endometrium. A differential screening procedure was performed on 800 clones from a day 13 pregnant cDNA library, from which day 13 cyclic endometrial mRNA had been subtracted [4]. The resulting nucleotide sequence data from the 800 clones were analyzed for similarity to all non-redundant database sequences using BLAST, and among these clones, granzyme B (GZMB) mRNA was identified numerous times. In real-time PCR analysis, however, expression levels of GZMB mRNA in the day 13 pregnant endometrium did not differ from that in the day 13 cyclic ones. Instead, high levels of GZMB mRNA expression were detected on day 19 of pregnancy, the phase of conceptus fixation (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Expression of granzyme B (GZMB) mRNA and protein in the equine endometrium. A: Real-time PCR analysis of GZMB mRNA in the equine endometrium. Total RNA was extracted from equine endometrium in day 13 cyclic and in days 13, 19, and 25 pregnant animals, lymph node and spleen. Bars represent means ± SE. An asterisk indicates a significant difference (P<0.05) when compared with the value from the cyclic endometrium. B: Western blot analysis of GZMB in the cyclic and days 13, 19, and 25 pregnant endometrium, lymph node and spleen.

Western blot analysis to detect GZMB protein was performed in the endometrium on day 13 cyclic and days 13, 19 and 25 of pregnancy, and in the lymph node and spleen in day 13 cyclic animals. This analysis detected GZMB protein in the endometrium and lymph node. Despite high mRNA expression on day 19, no significant increase in GZMB protein was detected on day 19. Rather, it appears that there was more GZMB protein in the pregnant endometrium than in cyclic ones (Fig. 1B).

Localization of GZMB in the equine endometrium

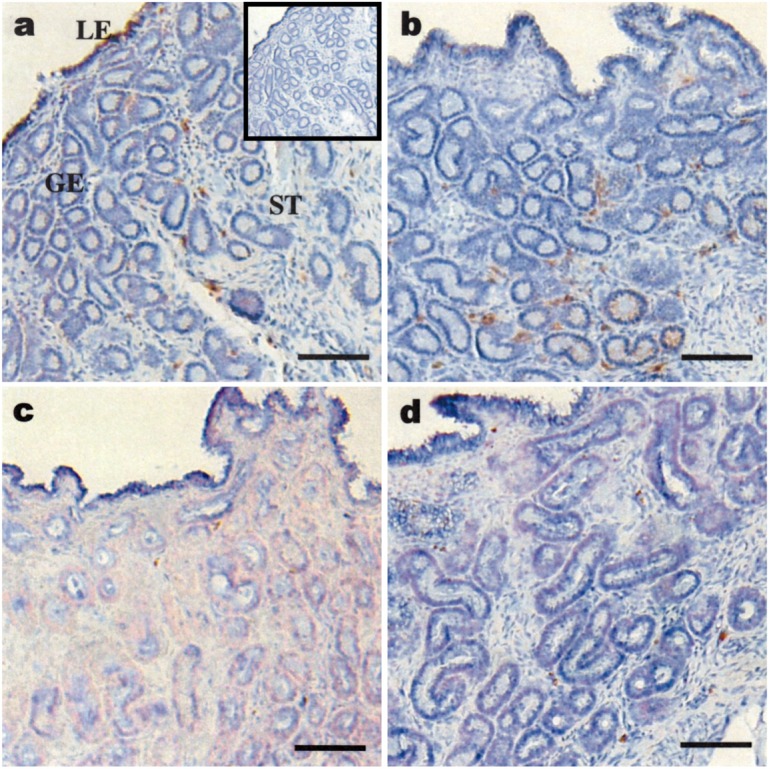

GZMB was localized in the day 13 cyclic and day 13 pregnant endometrium using a mouse anti-equine GZMB antibody [35]. It appeared that the staining intensity for GZMB was higher in day 13 pregnant endometria than in day 13 cyclic ones (Fig. 2a, b). In addition, the number of GZMB-positive cells in the subepithelial stroma around the glandular epithelium appeared to be higher in pregnant mares than in cyclic mares. In days 19 and 25 pregnant endometria, a few positive signals for GZMB were detected around the glandular epithelium (Fig. 2c, d).

Fig. 2.

Immunohistochemical analysis of GZMB in the equine endometrium. Immunohistochemical localization of GZMB in the cyclic (a) and pregnant days 13 (b), 19 (c) and 25 (d) equine endometrium. Detection of GZMB with mouse anti-equine GZMB antibody [35]; the inset (panel a, upper right corner) was the negative control with normal mouse IgG. All slides were counterstained with hematoxylin. LE, luminal epithelium; GE, glandular epithelium; ST, subepithelial stroma. Bar=100 μm.

Analysis of immune-related gene expression

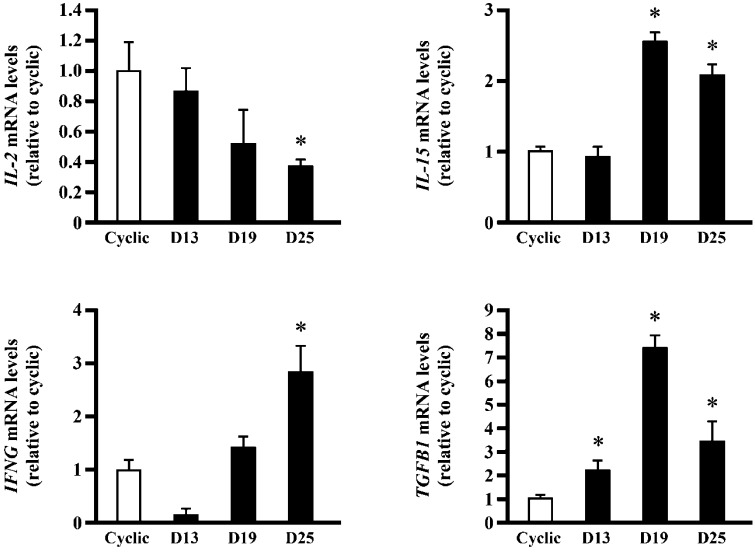

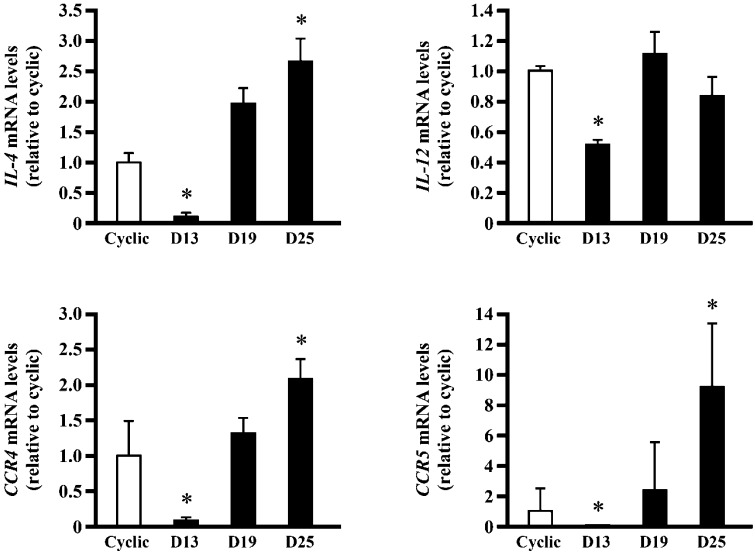

The level of IL-15 mRNA was high in days 19 and 25 pregnant endometria compared with that in cyclic ones (Fig. 3). TGFB1 mRNA expression in day 19 pregnant endometrium was higher than that in cyclic ones, whereas IFNG mRNA significantly increased on day 25. Expression of IL-2 mRNA gradually decreased as pregnancy progressed (Fig. 3). Transcript expressions of four genes, IL-4, IL-12, CCR4 and CCR5, in day 13 pregnant animals were reduced, whereas those of IL-4, CCR4 and CCR5 gradually increased toward day 25 pregnancy (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

mRNA expression of immune-related genes involved in the activation of T lymphocyte and NK cells in the equine endometrium. Total RNA was extracted from the equine endometrium in day 13 cyclic and in days 13, 19 and 25 pregnant animals, and real-time PCR analysis was performed to determine the expression of IL-2, IL-15, IFNG, and TGFB1 mRNA. Bars represent means ± SE. An asterisk indicates a significant difference (P<0.05) when compared with the value from the cyclic endometrium.

Fig. 4.

mRNA expression of immune-related genes involved in the activation of T helper cells in the equine endometrium. Total RNA was extracted from the equine endometrium in day 13 cyclic and in days 13, 19 and 25 pregnant animals, and real-time PCR analysis was performed to determine the expression of IL-4, IL-12, CCR4 and CCR5 mRNA. Bars represent means ± SE. An asterisk indicates a significant difference (P<0.05) when compared with the value from the cyclic endometrium.

Discussion

Implantation is the process by which the conceptus is to connect intimately with the maternal endometrium and to prepare for placental formation. Despite the fact that the endometrium is a rich source of immune cells during the implantation period, physiological mechanisms controlling these cell migrations have not been well characterized. More importantly, the conceptus expresses paternal antigens to which the mother could generate antibodies; however, the conceptus somehow escapes from the maternal immune system. By demonstration of immune-related gene expressions in the pregnant endometrium, it is possible that key molecules responsible for regulating these mechanisms could be identified.

In addition to residual endometrial NK (uNK) cells, peripheral NK cells expressing GZMB could have migrated particularly into the pregnant endometrium. In Western blot analysis, there appeared to be more GZMB in pregnant mares than in cyclic animals (Fig. 1B). In real-time PCR analysis, endometrial IL-15 mRNA expression was increased in days 19 and 25 pregnant mares (Fig. 3). It is possible that the proliferation of endometrial NK cells was induced by IL-15 on day 19, which caused an increase in GZMB mRNA expression in the endometrium on day 19 pregnancy. Because protein levels of GZMB did not correlate well with its mRNA, TGFB1, which is inhibitory to the activation of uNK cells, and IFNG, which is an inflammatory cytokine [36], were examined. Expression of TGFB1 mRNA significantly increased on day 19 (Fig. 3). Although TGFB1 inhibition of GZMB synthesis was not investigated in this study, the activity of endometrial NK cells on the days of embryonic fixation could be regulated by TGFB1. Observation in which IFNG expression increased on day 25 when TGFB1 decreased suggests the possibility that IFNG was enhanced due to the decrease in the expression of TGFB1.

It is generally accepted that the balance between Th1 and Th2, cell numbers and cytokine productions, is directly related to the success and maintenance of pregnancy. Because IFNG is a typical Th1 cytokine and its mRNA expression was high in this study, whether or not genes involved in endometrial Th1 as well as Th2 cytokine mRNAs were also examined. It was found that IL-4, CCR5 and CCR4 mRNAs were increased on day 25 of pregnancy. IL-12 and IL-4 induce native CD4+ T cells to differentiate into Th1 and Th2, respectively, and CCR5 and CCR4 are cytokine receptors that are expressed in Th1 and Th2 cells, respectively [37]. These results indicate that both Th1- and Th2-regulated immune reactions could also be functional in the endometrium of pregnant mares.

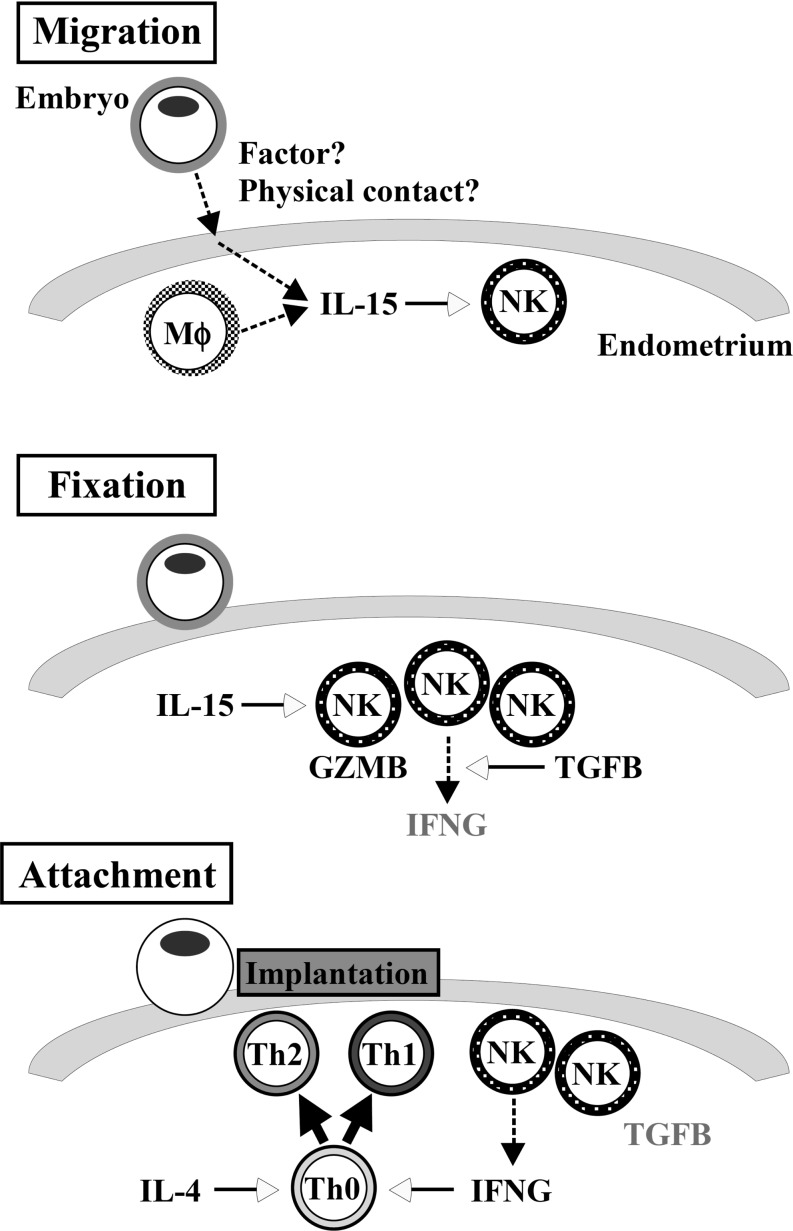

Although mRNA expression of immune-related genes was carefully studied during the implantation period, protein levels of these mRNAs were not characterized. Based on these results, however, we propose a model of the endometrial immune system during early pregnancy in the mare (Fig. 5). Under the condition of increases in IL-15 expression, NK cells are induced for their activation and proliferation in the endometrium during embryonic migration. Whereas TGFB1 exhibits an upward trend and IFNG expression is limited to day 19 pregnancy, NK cell activity is limited, and production of GZMB is down-regulated. After embryonic fixation on day 19, IFNG expression increases as a result of the decrease in TGFB1. This increase in IFNG induces activation and proliferation of Th1 cells. If, in fact, Th1 cells become predominant during the implantation period, it may result in pregnancy failure. On day 25, however, IL-4-induced Th2 differentiation counteracts Th1 activity through the production of Th2 cytokines, resulting in the balanced immune environment in the pregnant uterus.

Fig. 5.

Possible model of immune-related gene expressions and their interactions during periods covering days 13, 19 and 25, while the equine conceptus goes through three stages of development; migration (day 13, Upper), fixation (day 19, Middle), and attachment (day 25, Lower) to the uterine endometrium. Intrauterine migration induces endometrial IL-15, resulting in NK cell recruitment. These uNK cells produce GZMB and induce other immune-related gene expressions at the phase of conceptus fixation. As the capsule subsides and conceptus attachment proceeds, Th1 and Th2 cells are recruited into the attachment area of the endometrium. These sequential gene expressions may be required for equine pregnancy to proceed.

In the mare, there are many characteristic features operative during early pregnancy. Because of its long and slow implantation process, the mare is a quite effective animal species to dissect the complex immune interactions between the maternal endometrium and conceptuses during the early implantation period. Further studies on horse implantation may result in novel knowledge that has not been found in other animal models in previous investigations.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by research funds from the Japan Racing Association (JRA) and by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (18108004) to KI from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS).

References

- 1.Hunt K. Horse Evolution. TalkOringins Archive, 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ginther OJ. Reproductive Biology of the Mare: Basic and Applied Aspects, 2nd ed. Cross Plains: Equiservices; 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen WR. The physiology of early pregnancy in the mare. AAEP Proceedings 2000; 46: 338–354 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haneda S, Nagaoka K, Nambo Y, Kikuchi M, Nakano Y, Matsui M, Miyake Y, Macleod JN, Imakawa K. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist expression in the equine endometrium during the peri-implantation period. Domest Anim Endocrinol 2009; 36: 209–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu CC, Persechini PM, Young JD. Perforin and lymphocyte-mediated cytolysis. Immunol Rev 1995; 146: 145–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trapani JA. Granzymes: a family of lymphocyte granule serine proteases. Genome Biol2001; 2: 3014.1-3014.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jokhi PP, King A, Sharkey AM, Smith SK, Loke YW. Screening for cytokine messenger ribonucleic acids in purified human decidual lymphocyte populations by the reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction. J Immunol 1994; 153: 4427–4435 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jokhi PP, King A, Loke YW. Cytokine production and cytokine receptor expression by cells of the human first trimester placental-uterine interface. Cytokine 1997; 9: 126–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rieger L, Kammerer U, Hofmann J, Sutteflin M, Dietl J. Choriocarcinoma cells modulate the cytokine production of decidual large granular lymphocytes in coculture. Am J Reprod Immunol 2001; 46: 137–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eriksson M, Meadows SK, Wira CR, Sentman CL. Unique phenotype of human uterine NK cells and their regulation by endogenous TGF-β. J Leukoc Biol 2004; 76: 667–675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kitaya K, Yasuda J, Yagi I, Tada Y, Fushiki T, Honjo H. IL-15 expression at human endometrium and decidua. Biol Reprod 2000; 63: 683–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelly RW, King AE, Critchley HO. Cytokine control in human endometrium. Reproduction 2001; 121: 3–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaouat G, Zourbas S, Ostojic S, Lappree-Delage G, Dubanchet S, Martal J. A brief review of recent data on some cytokine expressions at the matemo-foetal interface which might challenge the classical Th1/Th2 dichotomy. J Reprod Immunol 2002; 53: 241–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golander A, Banett JR, Tyrey L, Fletcher WH, Handwerger S. Differential synthesis of human placental lactogen and human chorionic gonadotropin in vitro. Endocrinology 1978; 102: 597–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maslar IA, Riddick DH. Prolactin production by human endometrium during the normal menstrual cycle. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1979; 135: 751–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okada S, Okada H, Sanexumi M, Nakajima T, Yasuda K, Kanzaki H. Expression of interleukin-15 in human endometrium and decidua. Mol Hum Reprod 2000; 6: 75–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chegini N, Ma C, Roberts M, Williams RS, Ripps BA. Differential expression of interleukins (IL) IL-13 and IL-15 throughout the menstrual cycle in endometrium of normal fertile women and women with recurrent spontaneous abortion. J Reprod Immunol 2002; 56: 93–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dunn CL, Crithley HOD, Kelly RW. IL-15 regulation in human endometrial stromal cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002; 87: 1898–1901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bellone G, Aste-Amezaga M, Trinchieri G, Rodeck U. Regulation of NK cell function by TGF-beta 1. J Immunol 1995; 155: 1066–1073 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naganuma H, Sasaki A, Satoh E, Nagasaka M, Nakano S, Isoe S, Tasaka K, Nukui H. Transforming growth factor-β inhibits interferon-γ secretion by lymphokine-activated killer cells stimulated with tumor cells. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1996; 36: 789–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seo N, Tokura Y, Takigawa M, Egawa K. Depletion of IL-10- and TGF-β-producing regulatory γδ Tcells by administering a daunomysin-conjugated specific monoclonal antibody in early tumor lesions augments the activity of CTLs an NK cells. J Immunol 1999; 163: 242–249 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Castriconi R, Cantoni C, Chiesa MD, Vitale M, Marcenaro E, Conte R, Biassoni R, Bottino C, Moretta L, Moretta A. Transforming growth factor β1 inhibits expression of NKp30 and NKG2D receptors: Consequences for the NK-mediated killing of dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003; 100: 4120–4125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayashi H, Inoue Y, Tsutsui H, Okamura H, Nakanishi K, Onozaki K. TGFbeta down-regulates IFN-gamma production in IL-18 treated NK cell line LNK5E6. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2003; 300: 980–985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kehrl JH, Wakefield LM, Roberts AB, Jakowlew S, Alvarez-Mon M, Derynck R, Sporn MB, Fauci AS. Production of transforming growth factor beta by human T lymphocytes and its potential role in the regulation of T cell growth. J Exp Med 1986; 163: 1037–1050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruegemer JJ, Ho SN, Augustine JA, Schlager JW, Bell MP, McKean DJ, Abraham RT. Regulatory effects of transforming growth factor-beta on IL-2- and IL-4 dependent T cell-cycle progression. J Immunol 1990; 144: 1767–1776 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nelson BJ, Ralph P, Green SJ, Nacy CA. Differential susceptibility of activated macrophage cytotoxic effector reactions to the suppressive effects of transforming growth factor-beta 1. J Immunol 1991; 146: 1849–1857 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wira CR, Roche MA, Rossoll RM. Antigen presentation by vaginal cells: role of TGFβ as a mediator of estradiol inhibition of antigen presentation. Endocrinology 2002; 143: 2872–2879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wegmann TG, Lin H, Guilbert L, Mosmann TR. Bidirectional cytokine interactions in the maternal-fetal relationship: is successful pregnancy a TH2 phenomenon? Immunol Today 1993; 14: 353–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hunt JS, Roby KF. Implantation factors. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1994; 37: 635–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Croy BA, Esadeg S, Chantakru S, van den Heuvel M, Paffaro VA, He H, Black GP, Ashkar AA, Kiso Y, Zhang J. Update on pathways regulating the activation of uterine Natural Killer cells, their interactions with decidual spiral arteries and homing of their precursors to the uterus. J Reprod Immunol 2003; 59: 175–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chaouat G, Ledee-bataille N, Zourbas S, Dubanchet S, Sandra O, Martal J, Ostojojic S, Frydman R. Implantation: can immunological parameters of implantation failure be of interest for pre-eclampsia? J Reprod Immunol 2003; 59: 205–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nambo Y, Nagaoka K, Tanaka Y, Nagamine N, Shinbo H, Nagata S, Yoshihara T, Watanabe G, Groome NP, Taya K. Mechanisms responsible for increase in circulating inhibin levels at the time of ovulation in mares. Theriogenology 2002; 57: 1707–1717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kikuchi M, Nakano Y, Nambo Y, Haneda S, Matshui M, Miyake Y, Macleod JN, Nagaoka K, Imakawa K. Production of Calcium Maintenance Factor Stanniocalcin-1 (STC1) by the Equine Endometrium During the Early Pregnant Period. J Reprod Dev 2011; 57: 203–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sakurai T, Sakamoto A, Muroi Y, Bai H, Nagaoka K, Tamura K, Takahashi T, Hashizume K, Sakatani M, Takahashi M, Godkin JD, Imakawa K. Induction of endogenous interferon Tau gene transcription by CDX2 and high acetylation in bovine nontrophoblast cells. Biol Reprod 2009; 80: 1223–1231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Piuko K, Bravo IG, Mueller M. Identification and characterization of equine granzyme B. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2007; 118: 239–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meadows SK, Eriksson M, Barber A, Sentman CL. Human NK cell IFN-γ production is regulated by endogenous TGF-β. Int Immunopharmacol 2006; 6: 1020–1028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andrew DP, Ruffing N, Kim CH, Miao W, Heath H, Li Y, Murphy K, Campbell JJ, Butcher EC, Wu L. C-C chemokine receptor 4 expression defines a major subset of circulating nonintestinal memory T cells of both Th1 and Th2 potential. J Immunol 2001; 166: 103–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]