Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative mental illness characterized memory loss, multiple cognitive impairments and changes in the personality and behavior. The purpose of our study was to determine the interaction between monomeric and oligomeric Aβ, and phosphorylated tau in AD neurons. Using postmortem brains from AD patients at different stages of disease progression and control subjects, and also from AβPP, AβPPxPS1, and 3XAD.Tg mice, we studied the physical interaction between Aβ and phosphorylated tau. Using immunohistological and double-immunofluorescence analyses, we also studied the localization of monomeric and oligomeric Aβ with phosphorylated tau. We found monomeric and oligomeric Aβ interacted with phosphorylated tau in neurons affected by AD. Further, these interactions progressively increased with the disease process. These findings lead us to conclude that Aβ interacts with phosphorylated tau and may damage neuronal structure and function, particularly synapses, leading to cognitive decline in AD patients. Our findings suggest that binding sites between Aβ and phosphorylated tau need to be identified and molecules developed to inhibit this interaction.

Keywords: Amyloid beta, amyloid-β protein precursor, phosphorylated tau, synapses, cognitive decline

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a late-onset, age-dependent neurodegenerative disease, characterized by the progressive decline of memory and cognitive functions, and changes in behavior and personality. Histopathological examination of postmortem brains from AD patients has revealed two major pathological changes: extracellular amyloid beta (Aβ) deposits and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) in the brain regions of the learning and memory [1–4]. Other changes include synaptic dysfunction, mitochondrial structural and functional abnormalities, inflammatory responses, and neuronal loss [1–10]. Several factors have been implicated in late-onset AD, including life style, diet, environmental exposure and Apolipoprotein allele E4 genotype and polymorphisms in several genes [11]. Early onset and familial AD is caused by several mutations in amyloid precursor proteins and in presenilin 1 and presenilin 2 genes. Despite the tremendous progress that researchers have made in better understanding AD progression and pathogenesis, we still do not have early detectable markers and therapeutic agents that delay or prevent AD.

Aβ is a major component of neuritic plaques in the AD brain. Aβ in AD brains is a product of the APP gene, cleaved via sequential proteolysis of β secretase and γ secretase. Cleavage by γ secretase generates two major forms of Aβ: a shorter form with 40 amino acid residues and a longer form with 42 amino acids. The longer form is extremely toxic and has the capability to self-aggregate, to form oligomers, to participate in fibrillogenesis, and to accumulate into Aβ deposits [4,12]. Levels of Aβ in brains from AD patients are controlled by the production, clearance, and degradation of Aβ. Recent studies revealed that soluble intraneuronal Aβ trigger and facilitate phosphorylation of tau in AD brains [13,14].

Tau is a major microtubule-associated protein that plays a key role in the outgrowth of neuronal processes and the development of neuronal polarity. Tau promotes microtubule assembly and stabilizes microtubules in neurons [15]. Tau is abundantly present in the central nervous system and is predominantly expressed in neuronal axons [16]. Evidence suggests that hyperphosphorylated tau is critically involved in AD pathogenesis, particularly by impairing axonal transport of APP and subcellular organelles, including mitochondria in neurons affected by AD [17,18].

Recently, several histological and biochemical studies found that Aβ and phosphorylated tau are colocalized in AD neurons [19–22]. Fein and colleagues [21] examined the regional distribution and co-localization of Aβ and phosphorylated tau in synaptic terminals of neurons from postmortem AD brains. They found both Aβ and phosphorylated tau localized at synaptic terminals in the brain region known to be the earliest affected area in AD: the entorhinal cortex. Takahashi and colleagues [22] found hyperphosphorylated tau co-localized with Aβ42 in dystrophic neurites surrounding Aβ plaques. They also found hyperphosphorylated tau mislocalized near Aβ42, on tubular-filamentous structures, and in clusters associated with the microtubule network in dendritic profiles in neurons from Tg2576 mice. Similar mislocalizations of hyperphosphorylated tau were also found in biopsies of brain tissues from AD patients. However, the mechanisms underlying the co-localization of Aβ and phosphorylated tau in AD progression, and the impact of co-localized Aβ and phosphorylated tau, are unclear.

In the current study, we sought to determine 1) the relationship between Aβ and phosphorylated tau using co-immunoprecitation and colocalization methods, using AD postmortem brains and brains from mice that produce Aβ and phosphorylated tau and 2) whether the physical interaction between co-localized Aβ and phosphorylated tau in AD neurons increases in disease progression.

MATERIALS AND MATHODS

Postmortem brain sections from AD patients

Twenty postmortem brain specimens from AD patients and age-matched control subjects were obtained from the Harvard Tissue Resource Center, as described previously [23]. Fifteen specimens were from patients diagnosed with AD at different stages of disease progression, according to Braak stages I and II (early AD) (n = 5), III and IV (definite AD) (n = 5), and V and VI (severe AD) (n = 5). Fve specimens were from age-matched control subjects. The specimens were removed from the frontal cortex, quick-frozen, and formalin-fixed (BA9)

AβPP, AβPPxPS1 and 3XTg.AD transgenic mice

Using AβPP (Tg2576 line) [24], AβPPxPS1 [25] and 3XTg.AD mice [26] and age-matched WT littermates (controls), we studied the localization and interaction between Aβ and hyperphosphorylated tau at different stages of AD progression. The AβPP, AβPPxPS1, and 3XTg.AD mice) were housed at the Oregon National Primate Research Center at Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU). The OHSU Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all procedures for animal care, according to guidelines set forth by the National Institutes of Health.

Antibodies used in this study

To characterize the interaction of Aβ with phosphorylated tau, we used a hyperphosphorylated antibody and antibodies that recognize the Aβ peptide monomeric (6E10) and oligomeric (A11) (Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA) [27]. The details of antibodies used in this study are given in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Summary of antibody dilutions and conditions used in co-immunoprecipitation analysis and western blot analysis

| Co-IP PHF-Tau (S396) | Rabbit monoclonal 10 ug/500 ug protein | Abcam, Cambridge, MA | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Co-IP 6E10 | Mouse monoclonal 10 ug/500 ug protein | Covance, San Diego, CA | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| WB A11 | Rabbit polyclonal 1:400 | Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA | Donkey anti-rabbit HRP 1:10,000 | GE Healthcare Amersham, Piscataway, NJ |

| WB PHF-Tau (S396) | Rabbit monoclonal 1:400 | Abcam, Cambridge, MA | Donkey anti-rabbit HRP 1:10,000 | GE Healthcare Amersham, Piscataway, NJ |

Table 2.

Summary of antibody dilutions and conditions used in immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence analysis in human and mouse brain tissues.

| Marker | Primary antibody – species and dilution | Purchased from Company, City and State | Secondary antibody, dilution, Alexa fluorescent dye | Purchased from Company, City and State |

| PHF-Tau (S396) | Rabbit monoclonal 1:100 | Abcam, Cambridge, MA | Goat anti-rabbit biotin 1:300, HRP-streptavidin (1: 100), TSA-Alexa488 | KPL, Gaithersburg, MD Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR |

| PHF-Tau (AT8) | Mouse monoclonal 1:100 | Pierce Biotechnology, Inc. Rockford, IL | Goat anti-mouse biotin 1:300, HRP-streptavidin (1: 100), TSA-Alexa594 | KPL, Gaithersburg, MD Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR |

| 6E10 | Mouse monoclonal 1:300 | Covance, San Diego, CA | Goat anti-mouse biotin 1:300, HRP-streptavidin (1: 100), TSA-Alexa594 | KPL, Gaithersburg, MD Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR |

| Aβ1–42 | Rabbit polyclonal 1:35 | Millipore, Temicula, CA | Goat anti - rabbit biotin 1:300, HRP-streptavidin (1: 100), TSA-Alexa488 | KPL, Gaithersburg, MD Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR |

| A11 | Rabbit polyclonal 1:400 | Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA | Goat anti - rabbit biotin 1:300, HRP-streptavidin (1: 100), TSA-Alexa488 | KPL, Gaithersburg, MD Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR |

Co-immunoprecipitation of Aβ and phosphorylated tau

To determine whether Aβ (monomers and oligomers) interact with phosphorylated tau, we used cortical protein lysates from AD patients and control subjects, from AβPPxPS1 and 3XAD.Tg mice, and from nontransgenic, wild-type (WT) mice. We performed co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) assays using the Dynabeads Kit for Immunoprecipitation (Invitrogen). Briefly, 50 µL of Dynabeads containing protein G was incubated with 10 µg of anti-phosphorylated or 6E10 antibodies, with rotation, for 1 h at room temperature. We used all the reagents and buffers provided in the kit. Details of antibodies used for co-IP and western blotting are given Table 1. The Dynabeads were then washed once with a washing buffer and incubated with rotation overnight, with 500 µg of lysate protein at 4°C. The incubated Dynabead antigen/antibody complexes were washed again 3 times with a washing buffer, and an immunoprecipitant was eluted from the Dynabeads, using a NuPAGE LDS sample buffer. The Aβ and phosphorylated tau IP elute was loaded onto a 4–20 gradient gel, followed by western blot analysis of Aβ monomeric (6E10) and oligomeric-specific A11 antibodies, and of phosphorylated tau We also cross-checked the results by performing co-IP experiments, using both anti-Aβ and anti-phosphorylated tau antibodies.

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence analysis

Using immunofluorescence techniques, we sought to determine whether phosphorylated tau was localized in the frontal cortex of postmortem specimens from AD patients. The specimens were paraffin-embedded, and sections were cut into 15-µm width. We deparaffinized the sections by washing them with xylene for 10 min and then washing them for 5 min in a serial dilution of alcohol (95, 70, and 50%). The sections were then washed once for 10 min in double-distilled H2O, and then for six more times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4), at 5 min each time. To reduce the autofluorescence of brain specimens, we treated the deparaffinized sections with sodium borohydrate twice, for 30 min each time, in a freshly prepared 0.1% sodium borohydrate solution dissolved in PBS (pH 8.0). We then washed the sections three times with PBS (pH 7.4), for 5 min each. Next the sections were boiled with sodium citrate buffer for 25 minutes for epitope retrieval. To increase antibody permeability, the brain sections were treated with 0.5% Triton dissolved in PBS (pH 7.4). To block the endogenous peroxidase, sections were treated with 3% H2O2 for 15 min. The sections were then blocked with a solution (0.5% Triton in PBS + 10% goat serum + 1% bovine serum albumin) for 1 h. They were incubated overnight at room temperature with two antibodies: the anti-Aβ – 6E10 antibody (mouse monoclonal, 1:300 dilution; Covance, San Diego, CA), Anti-Aβ 1–42 (polyclonal 1:35 (Millipore, Temicula, CA), and the anti-phosphorylated tau antibody (1:100, mouse monoclonal; Pierce Biotechnology, Inc., Rockford, IL). On the day after the primary antibody incubation, the sections were washed once with 0.1% Triton in PBS and then incubated with appropriate biotinylated secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Details of the secondary antibodies are given in Table 2. The sections were washed with PBS three times for 10 min each and then incubated with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated streptavidin solution (Invitrogen) for 1 h. The sections were washed three more times with PBS (pH 7.4) for 10 min each and then treated with Tyramide Alexa 594 (red) or Alexa 488 (green) (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 10 min at room temperature. They were cover-slipped with Prolong Gold and photographed with a confocal microscope.

Double-labeling immunofluorescence analysis

To determine the interaction between Aβ and phosphorylated tau we conducted double-labeling immunofluorescence analysis, using an anti-phosphorylated tau antibody and Aβ antibodies, 6E10 and Aβ1–42. As described above, brain sections from patients with AD and control subjects were deparaffinized and treated with sodium borohydrate to reduce autofluorescence. For the first labeling, the sections were incubated with appropriate primary antibodies overnight at room temperature. On the day after this incubation, the sections were washed with 0.5% Triton in PBS and then incubated with a secondary biotinylated anti-rabbit antibody, at a 1:300 dilution (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) or with a secondary biotinylated anti-mouse antibody (1:300) for 1 h at room temperature (see Table 2). The antibodies were incubated for 1 h in an HRP-conjugated streptavidin solution (Molecular Probes). The sections were then washed three times with PBS for 10 min each at pH 7.4. They were then treated with Tyramide Alexa488 for 10 min at room temperature. For the second labeling, the sections were incubated overnight with an anti-phosphorylated tau antibody (1:100, mouse monoclonal; Pierce Biotechnology, Inc.) at room temperature. They were incubated with a donkey, anti-mouse secondary antibody that was labeled with Alexa 594 for 1 h at room temperature. The sections were cover-slipped with Prolong Gold and photographed with a confocal microscope.

We also performed double-labeling analyses of Aβ and phosphorylated tau, using mid-brain sections from AβPPxPS1 and 3XTg.AD mice, and Aβ and phosphorylated tau antibodies as described above.

RESULTS

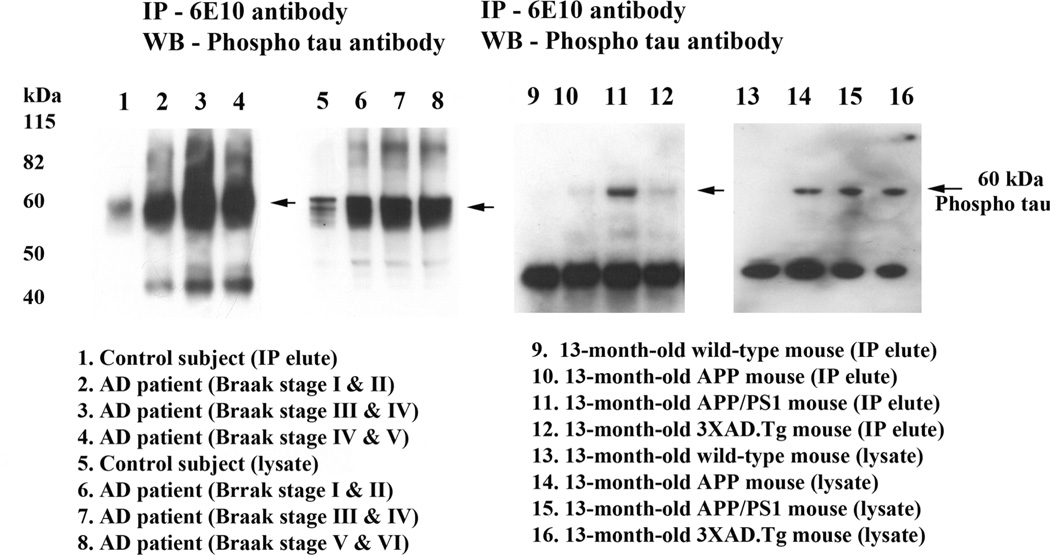

Monomeric Aβ interaction with phosphorylated tau

To determine whether Aβ monomers interact with phosphorylated tau, we conducted co-IP analysis, using cortical protein lysates from brains of AD patients (Braak stages III & IV and V & VI) and of control subjects (Braak stage 0), and from brains of AβPP, AβPPxPS1 and 3xAD.Tg mice and of age-matched, non-transgenic WT mice; and using Aβ (6E10 monoclonal) and phosphorylated tau antibodies (see Table 1). Our IP analysis of the Aβ antibody and immunoblotting analysis of phosphorylated tau revealed a 60 kDa phosphorylated tau band in Aβ IP elutes from AD patients (Braak stages I & II, III & IV and V & VI (lanes 2–4) and from AβPP (lane 10), AβPPxPS1 (lane 11), and 3xAD.Tg mice (lane 12) (Fig. 1). Further, the intensity of interaction increased as the disease progressed. In other words, the strongest interactions were found in specimens from AD patients at more advanced stages of disease progression (Braak stages V & VI, and III & IV). We also found very little or no interaction between Aβ and phosphorylated tau in the brain specimens from the control subjects and the non-transgenic, WT mice, suggesting that Aβ monomers interact with phosphorylated tau in a disease-progression manner.

Figure 1.

Co-immunoprecipitation analysis of Aβ and phosphorylated tau in brain tissues from AD patients, and AβPP, AβPPxPS1 and 3XTg.AD mice. Immunoprecipitation with the Aβ (6E10) antibody and immunoblotting with phosphorylated tau, demonstrating the presence of phosphorylated tau in immunoprecipitation elutes of Aβ. The specificity of Aβ (6E10) antibody was verified in our previous publication, Manczak et al [23].

Oligomeric Aβ with phosphorylated tau

To determine whether oligomeric Aβ interacts with phosphorylated tau, we conducted co-IP analysis, using cortical protein lysates from the brains of AD patients and of the AβPP, AβPPxPS1, 3xTg.AD transgenic mice and the WT mice; and using oligomeric Aβ-specific antibody [27] and phosphorylated tau antibody. As shown in Fig. 2, our co-IP analysis revealed a 60 kDa oligomeric Aβ band in the phosphorylated tau IP elutes in the brains from AD patients (Braak stages III & IV, and V & VI) (lanes 2–3) and from the APP (lane 8) and APPxPS1 (lane 9) mice (Fig. 2). Further, we also found a strong interaction between oligomeric Aβ and phosphorylated tau in brain specimens from AD patients at Braak stage V and VI, relative to those at Braak III and IV, indicating that the interaction increased with disease progression. However, we also noticed a faint band in the phosphorylated tau IP elutes from control subjects and non-transgenic WT mice. These findings suggest that phosphorylated tau interacts mainly with oligomeric Aβ.

Figure 2.

Co-immunoprecipitation analysis of oligomeric Aβ and phosphorylated tau in brain tissues from AD patients and control subjects, and AβPP, AβPPxPS1 and 3XTg.AD mice. Immunoprecipitation with the phosphorylated tau antibody and immunoblotting with oligomeric Aβ antibody, demonstrating the presence of oligomeric Aβ in immunoprecipitation elutes of phosphorylated tau. The specificity of phosphorylated tau antibody was verified in our previous publication, Manczak and Reddy [30].

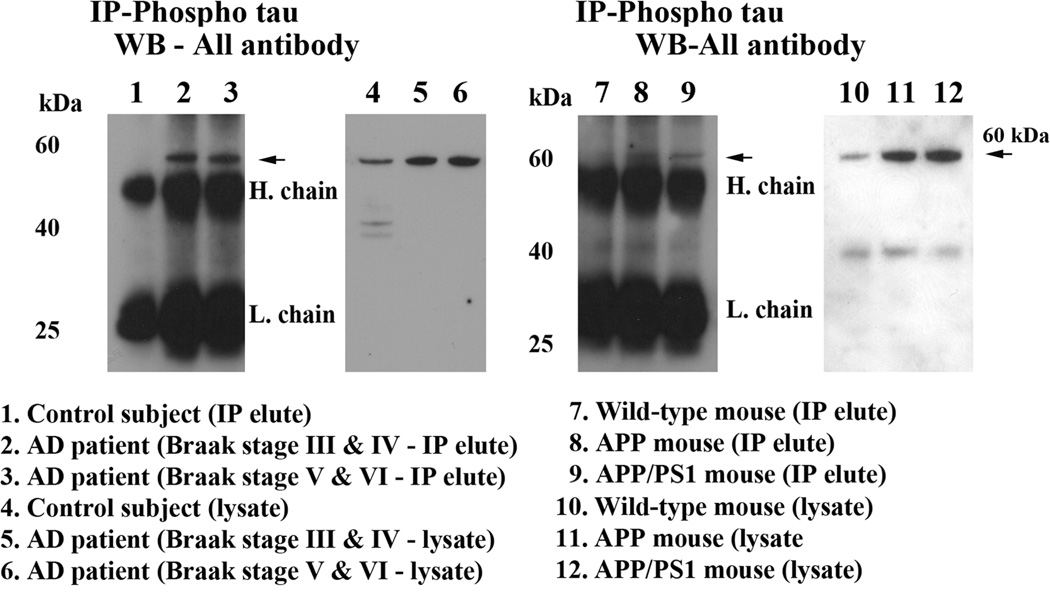

Immunostaining analysis of phosphorylated tau

We performed immunostaining analysis of phosphorylated tau, using brain sections from AD postmortem brains and phosphorylated tau antibodies. As shown in Fig. 3, we found phosphorylated tau in frontal cortex brain sections from AD patients but not those from control subjects (data not shown). Arrows indicate the localization of phosphorylated tau in AD neurons.

Figure 3.

Immunostaining of phosphorylated tau in cortical sections from AD patients. The localization of phosphorylated tau at 40× original magnification (a), and the colocalization of phosphorylated tau at 100× original magnification (b, c and d).

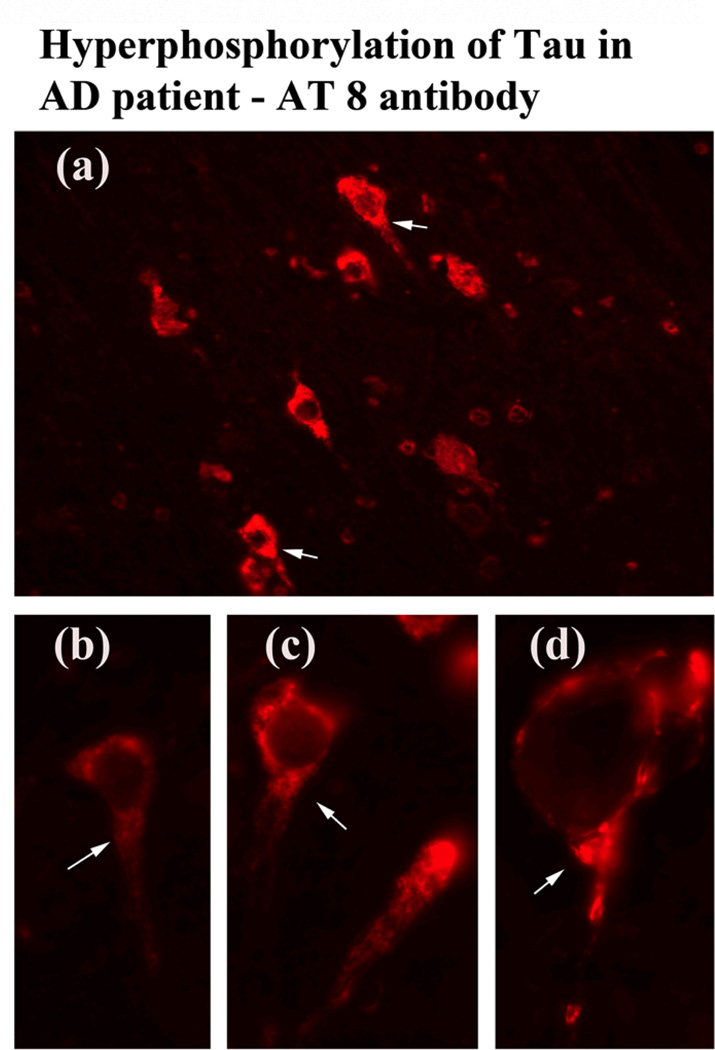

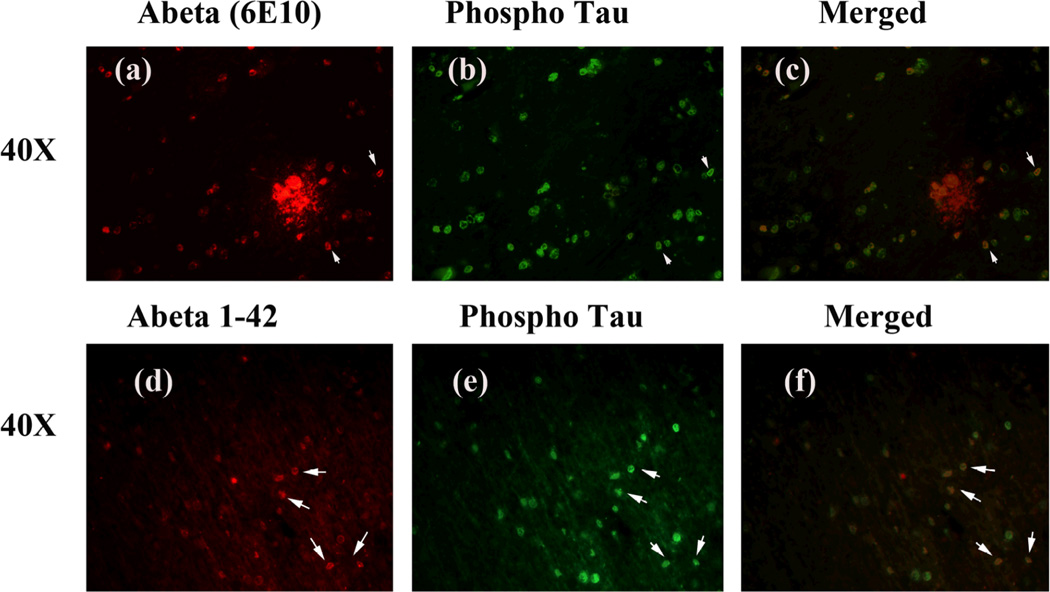

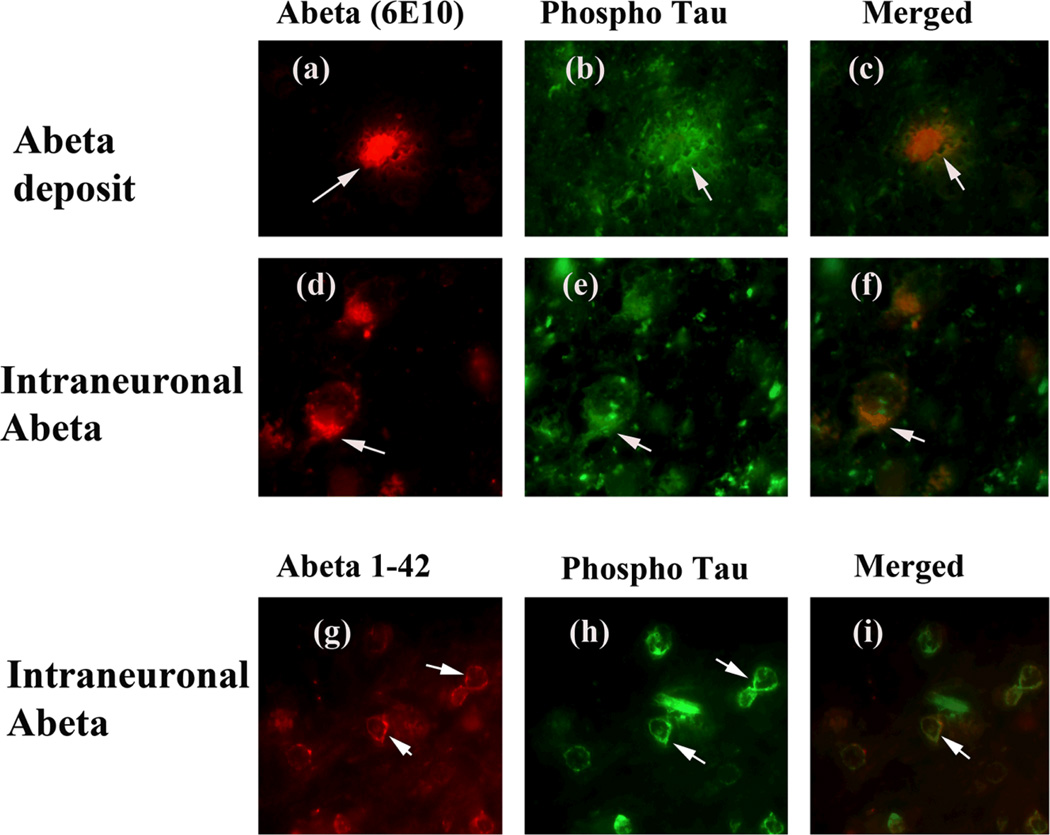

Double-labeling analysis of Aβ and phosphorylated tau in AD brains

To determine whether monomeric Aβ localizes and interacts with phosphorylated tau, we conducted double-labeling analysis of Aβ and phosphorylated tau, using specimens from the frontal cortex sections of AD patients and phosphorylated tau and Aβ (6E10) antibodies. The immunoreactivity of Aβ was colocalized with phosphorylated tau, indicating that phosphorylated tau interacts with Aβ (Fig. 4, low magnification) and (Fig. 5, high magnification). To determine whether longer form of Aβ (Aβ1–42) localizes with phosphorylated tau, we performed double-labeling analysis using Aβ1–42 and phosphorylated tau antibodies. As shown in Figs. 4 and 5 (lower panels), we found phosphorylated tau colocalized with Aβ1–42, strongly indicating that phosphorylated tau localizes with Aβ1–42. Interestingly, we found that not all Aβ immunoreactive neurons were positive with the phosphorylated tau antibody, indicating that Aβ may selectively interact with phosphorylated tau-positive neurons in AD neurons.

Figure 4.

Double-labeling immunofluorescence analysis of Aβ, and phosphorylated tau in cortical sections from AD patients. The localization of Aβ, using 6E10 antibody (a) and phosphorylated tau (b), and the colocalization of Aβ and phosphorylated tau (merged c) at 40× original magnification. The localization of Aβ1–42 (d) and phosphorylated tau (e) and colocalization (merged f) ant 40× magnification.

Figure 5.

Double-labeling immunofluorescence analysis of Aβ, and phosphorylated tau in cortical sections from AD patients. The localization of Aβ deposit, using 6E10 antibody (a) and phosphorylated tau (b), and the localization of Aβ deposit surrounded by phosphorylated tau (merged c) at 100× original magnification; and the localization of intraneuronal Aβ (d), phosphorylated tau (e) and the colocalization of Aβ and phosphorylated tau (merged f) at 100× original magnification. The localization of intraneuronal Aβ, using Aβ1–42 antibody (g), phosphorylated tau (h) and the colocalization of Aβ and phosphorylated tau (merged i) at 100× original magnification.

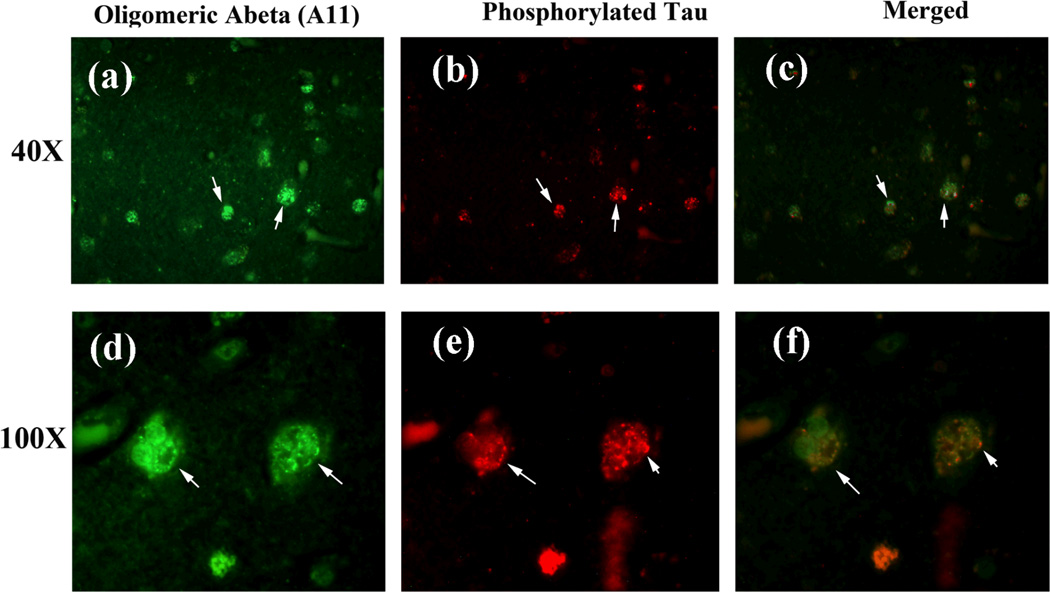

Double-labeling analysis of oligomeric Aβ and phosphorylated tau in AD brains

We also performed co-localization studies using oligomeric-specific A11 and phosphorylated tau antibodies. We found that the immunoreactivity of oligomeric Aβ was colocalized with phosphorylated tau (low magnification in the upper panel and high magnification in lower panel), suggesting that phosphorylated tau interacts with oligomeric Aβ.

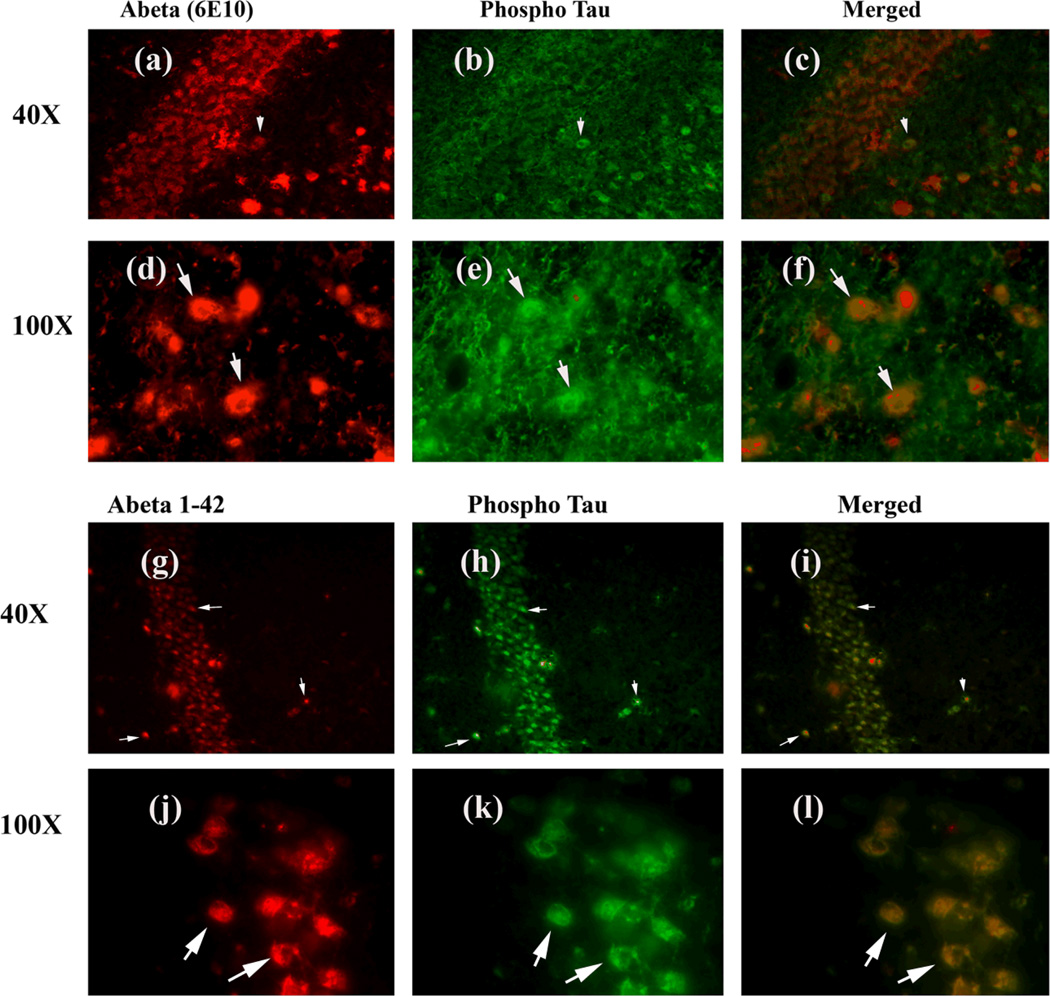

Double-labeling analysis of Aβ and phosphorylated tau in APPxPS1 mice

Using double-labeling analysis of Aβ and phosphorylated tau, we sought to determine whether Aβ colocalizes with phosphorylated tau in the hippocampal brain sections from AβPPxPS1 mice. As shown in the upper panels of Fig. 7, the immunoreactivity of Aβ was co-localized with phosphorylated tau, further suggesting that Aβ interacts with phosphorylated tau. Similar to AD postmortem brain sections, we also performed double-labeling analysis of phosphorylated tau and Aβ1–42, using phosphorylated tau and Aβ1–42 antibodies. As shown in Fig. 7 (lower panels), we found Aβ1–42 colocalized with phosphorylated tau, strongly indicating that longer form of Aβ colocalized with phosphorylated tau in hippocampal neurons. These results agreed with our IP findings of Aβ and phosphorylated tau, which showed in Figs. 1 and 2.

Figure 7.

Double-labeling immunofluorescence analysis of Aβ (6E10 antibody), and phosphorylated tau in hippocampal sections from 13-month-old AβPPxPS1 mouse. The localization of Aβ, using 6E10 antibody (a) and phosphorylated tau (b), and the colocalization of Aβ and phosphorylated tau (merged c) at 40× original magnification; the localization of Aβ (d); phosphorylated tau (e); and the colocalization of Aβ and phosphorylated tau (merged f) at 100× original magnification. The localization of Aβ using Aβ1–42 antibody (g) and phosphorylated tau (h), and the colocalization of Aβ and phosphorylated tau (merged i) at 40× original magnification; the localization of Aβ, using Aβ1–42 antibody (j); phosphorylated tau (k); and the colocalization of Aβ and phosphorylated tau (merged l) at 100× original magnification.

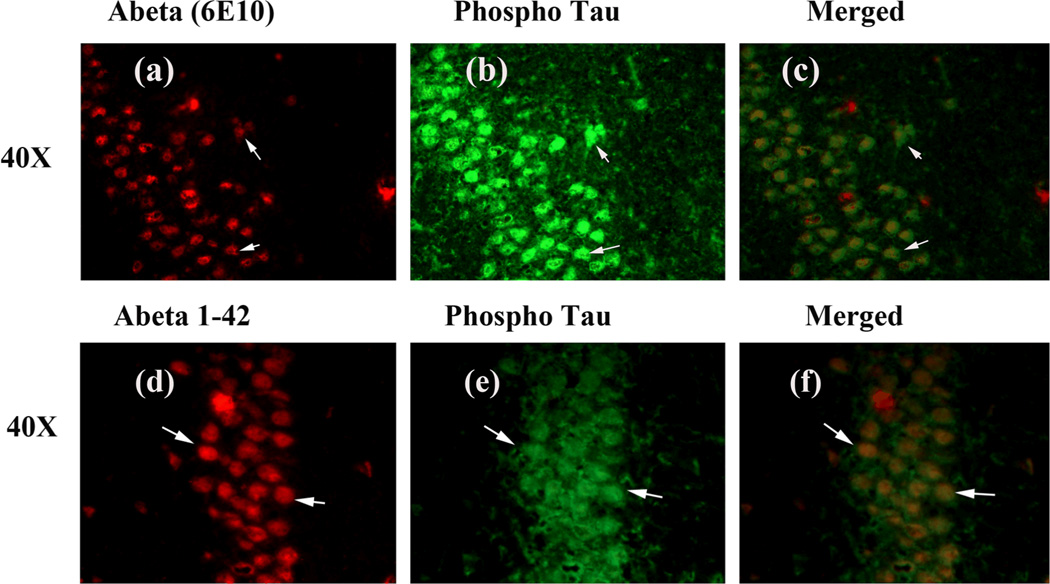

Double-labeling immunofluorescence analysis of Aβ and of phosphorylated tau in 3XTg.AD mice

To determine whether Aβ localizes and interacts with phosphorylated tau, we also conducted double-labeling analysis of Aβ (6E10 and Aβ1–42) and phosphorylated tau in tissues from the hippocampal sections of 3XTg.AD mice. As shown in Fig. 8, the immunoreactivities of Aβ (upper panel using 6E10 and lower panel using Aβ1–42 antibodies) were co-localized with phosphorylated tau immunoreactivity, again suggesting that Aβ may interact with phosphorylated tau in 3XTg.AD mice.

Figure 8.

Double-labeling immunofluorescence analysis of Aβ (6E10 antibody), and phosphorylated tau in hippocampal sections from 13-month-old 3XAD.Tg mouse. The localization of Aβ, using 6E10 antibody (a) and phosphorylated tau (b), and the colocalization of Aβ and phosphorylated tau (merged c) at 40× original magnification. The localization of Aβ, using Aβ1–42 antibody (d) and phosphorylated tau (e), and the colocalization of Aβ and phosphorylated tau (merged f) at 40× original magnification.

DISCUSSION

In the current study, we studied the physical interaction between monomeric and oligomeric Aβ and phosphorylated tau, using postmortem brains from AD patients at different stages of disease progression (Braak stages I and II, III and IV, and V and VI) and control subjects (Braak stage 0), and also brain tissues from three different transgenic mice lines (AβPP, AβPPxPS1 and 3XAD.Tg). Using immunohistological and double-immunofluorescence analyses, we also studied the co-localization of monomeric and oligomeric Aβ and phosphorylated tau, using postmortem brain sections from AD patients and AD transgenic mice. We found monomeric and oligomeric Aβ interacting with phosphorylated tau in AD neurons. Further, these interactions progressively increased with disease progression. We also verified phosphorylated tau interaction with Aβ using 2 different Aβ antibodies, 6E10 and Aβ1–42 and phosphorylated tau antibody in AD brains and AD transgenic mice (AβPPxPS1 and 3XAD.Tg). These findings lead us to conclude that Aβ interacts with phosphorylated tau, and that these interactions increase as AD progresses and may damage neuronal structure and function, particularly, if the interaction occurs at synapses.

Aβ interaction with phosphorylated Tau

Using co-IP analysis, we found that monomeric Aβ interacts with phosphorylated tau in AD postmortem brains and brain tissues from APP, APPxPS1 and 3XAD.Tg mice. Further, we also found oligomeric Aβ in IP elutes from phosphorylated tau, indicating that not only monomeric but also oligomeric Aβ is associated with phosphorylated tau. The intensity of interaction increased with disease progression, suggesting that disease progression dependent production of Aβ and phosphorylated tau are the factors that enhance the interaction.

Our double-labeling immunofluorescence analysis of monomeric, oligomeric Aβ and Aβ 1–42, and phosphorylated tau indicated that phosphorylated tau co-localize with Aβ and further support with our co-IP findings of Aβ and phosphorylated tau interaction. The increased interaction between Aβ and phosphorylated tau may be due to the increased production of Aβ in AD neurons, in later stages of disease progression. Further, the increase in oligomeric Aβ may lead to more robust interaction between Aβ and phosphorylated tau. Our co-localization findings agree with previous results from histological studies, finding that Aβ and phosphorylated tau are co-localized in synaptic terminals of AD neurons [21, 22]. Previously, Smith and colleagues [19] reported that tau directly interacts with a conformation-dependent domain of the amyloid beta-protein precursor (beta PP) encompassing residues beta PP714–723. The putative tau-binding domain includes beta PP717 mutation sites that are associated with familial forms of AD. These observations, together with current findings, strongly suggest that increased interactions and co-localization between Aβ and phosphorylated tau are toxic and specific to AD affected neurons. These abnormal interactions may damage neuronal structure and function, particularly at synapses, leading to cognitive decline in AD patients.

Treatment of amyloid β and phosphorylated tau binding sites as a therapeutic strategy

Findings from previous localization studies [19,21,22,28] and current IP and localization studies suggest that Aβ interacts with phosphorylated tau in AD neurons and that these interactions increase with disease progression, ultimately damaging neuronal structure and function. If these interactions damage neuronal structure and function, it is critically important to identify the binding sites of Aβ and phosphorylated tau and to develop molecules to inhibit their binding.

To identify such binding sites, using peptide membrane arrays, Guo et al. [29] investigated the sites where Aβ and tau interact. They found that where Aβ and tau interacted, Aβ binded to multiple tau peptides, especially those in exons 7 and 9 of the tau protein. They were able to sharply reduce or abolish this binding by phosphorylating specific serine and threonine residues of the tau protein. They also found that tau binded to multiple Aβ peptides in the mid to C-terminal regions of Aβ, and they were able to significantly decrease this binding by GSK3β phosphorylation of tau. They used surface plasmon resonance to determine the binding affinity of Aβ for tau and found it to be in the low nanomolar range and almost 1,000-fold higher than tau for itself. In soluble extracts from AD and control brain tissue, Guo et al. [29] also detected Aβ bound to soluble tau. However, further research is still needed to identify the binding sites particularly between Aβ and phosphorylated tau, if any, and to develop molecules that inhibit the interaction between Aβ and phosphorylated tau.

Based on structural biology and nuclear magnetic resonance studies, Miller et al [28] proposed a possible interaction between Aβ oligomers with the R2 domain of tau protein and may form a stable complex. This is an interesting notion, however, further research is needed to prove experimentally.

In summary, both monomeric Aβ and oligomeric Aβ co-localized with phosphorylated tau and interacted with phosphorylated tau, in brain tissues from AD brains and from the AβPP, AβPPXPS1, and 3XAD.Tg mouse lines. These interactions increased as AD progressed. Based on our findings together with those from other researchers, we propose that abnormal association of monomeric and oligomeric Aβ with phosphorylated tau in neurons, particularly at synapses, may cause synaptic damage, and it is this synaptic damage that may lead to cognitive decline in AD patients.

Figure 6.

Double-labeling immunofluorescence analysis of oligomeric Aβ, and phosphorylated tau in cortical sections from AD patients. The localization of oligomeric Aβ (a) and phosphorylated tau (b), and the colocalization of oligomeric Aβ and phosphorylated tau (merged c) at 40× original magnification; the localization of oligomeric Aβ (d), phosphorylated tau (e) and the colocalization of oligomeric Aβ, phosphorylated tau (merged f) at 100× original magnification.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by NIH grants AG028072, AG042178, and RR000163, P30-NS061800, and by a grant from the Medical Research Foundation of Oregon. We thank Dr. Anda Cornea (Imaging Core of the OHSU Oregon National Primate Research Center) for her assistance with the confocal microscopy. We also thank Drs. Karen Ashe, David Borchelt, Frank LaFerla and Salvotore Oddo for the generous gifts of AβPP, AβPPxPS1 and 3XTg.AD mice.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Authors have nothing to disclose regarding contents of this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer's disease: genes, proteins, and therapy. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:741–766. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mattson MP. Pathways towards and away from Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 2004;430:631–639. doi: 10.1038/nature02621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.LaFerla FM, Green KN, Oddo S. Intracellular amyloid-beta in Alzheimer's disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:499–509. doi: 10.1038/nrn2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reddy PH, Manczak M, Mao P, Calkins MJ, Reddy AP, Shirendeb U. Amyloid-beta and mitochondria in aging and Alzheimer's disease: implications for synaptic damage and cognitive decline. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20(Suppl 2):S499–S512. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang X, Su B, Siedlak SL, Moreira PI, Fujioka H, Wang Y, Casadesus G, Zhu X. Amyloid-beta overproduction causes abnormal mitochondrial dynamics via differential modulation of mitochondrial fission/fusion proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19318–19323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804871105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang X, Su B, Lee HG, Li X, Perry G, Smith MA, Zhu X. Impaired balance of mitochondrial fission and fusion in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2009;29:9090–9103. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1357-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Du H, Guo L, Yan S, Sosunov AA, McKhann GM, Yan SS. Early deficits in synaptic mitochondria in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:18670–18675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006586107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Du H, Guo L, Yan SS. Synaptic mitochondrial pathology in Alzheimer's disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;16:1467–1475. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swerdlow RH. Brain aging, Alzheimer's disease, and mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1812:1630–1639. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu X, Perry G, Smith MA, Wang X. Abnormal mitochondrial dynamics in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;33(Suppl 1):S253–S262. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-129005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reddy PH, Tripathi R, Troung Q, Tirumala K, Reddy TP, Anekonda V, Shirendeb UP, Calkins MJ, Reddy AP, Mao P, Manczak M. Abnormal mitochondrial dynamics and synaptic degeneration as early events in Alzheimer's disease: implications to mitochondria-targeted antioxidant therapeutics. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1822:639–649. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Querfurth HW, LaFerla FM. Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:329–344. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0909142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.LaFerla FM. Pathways linking Abeta and tau pathologies. Biochem Soc Trans. 2010;38:993–995. doi: 10.1042/BST0380993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chabrier MA, Blurton-Jones M, Agazaryan AA, Nerhus JL, Martinez-Coria H, LaFerla FM. Soluble Aβ promotes wild-type tau pathology in vivo. J Neurosci. 2012;32:17345–17350. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0172-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reddy PH. Abnormal tau, mitochondrial dysfunction, impaired axonal transport of mitochondria, and synaptic deprivation in Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res. 2011;1415:136–148. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.07.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brandt R, Hundelt M, Shahani N. Tau alteration and neuronal degeneration in tauopathies: mechanisms and models. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1739:331–354. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ittner LM, Götz J. Amyloid-β and tau--a toxic pas de deux in Alzheimer's disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:65–72. doi: 10.1038/nrn2967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vossel KA, Zhang K, Brodbeck J, Daub AC, Sharma P, Finkbeiner S, Cui B, Mucke L. Tau reduction prevents Abeta-induced defects in axonal transport. Science. 2010;330:198. doi: 10.1126/science.1194653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith MA, Siedlak SL, Richey PL, Mulvihill P, Ghiso J, Frangione B, Tagliavini F, Giaccone G, Bugiani O, Praprotnik D, Kalaria R, Perry G. Tau protein directly interacts with the amyloid beta-protein precursor: implications for Alzheimer's disease. Nat Med. 1995;1:365–369. doi: 10.1038/nm0495-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Delacourte A, Sergeant N, Champain D, Wattez A, Maurage CA, Lebert F, Pasquier F, David JP. Nonoverlapping but synergetic tau and APP pathologies in sporadic Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 2002;59:398–407. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.3.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fein JA, Sokolow S, Miller CA, Vinters HV, Yang F, Cole GM, Gylys KH. Co-localization of amyloid beta and tau pathology in Alzheimer's disease synaptosomes. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:1683–1692. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takahashi RH, Capetillo-Zarate E, Lin MT, Milner TA, Gouras GK. Co-occurrence of Alzheimer's disease β-amyloid and τ pathologies at synapses. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31:1145–1152. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manczak M, Calkins MJ, Reddy PH. Impaired mitochondrial dynamics and abnormal interaction of amyloid beta with mitochondrial protein Drp1 in neurons from patients with Alzheimer's disease: implications for neuronal damage. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:2495–2509. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsiao K, Chapman P, Nilsen S, Eckman C, Harigaya Y, Younkin S, Yang F, Cole G. Correlative memory deficits, Abeta elevation, and amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Science. 1996;274:99–102. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5284.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borchelt DR, Thinakaran G, Eckman CB, Lee MK, Davenport F, Ratovitsky T, Prada CM, Kim G, Seekins S, Yager D, Slunt HH, Wang R, Seeger M, Levey AI, Gandy SE, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Price DL, Younkin SG, Sisodia SS. Familial Alzheimer's disease-linked presenilin 1 variants elevate Abeta1–42/1–40 ratio in vitro and in vivo. Neuron. 1996;17:1005–1013. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80230-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oddo S, Caccamo A, Shepherd JD, Murphy MP, Golde TE, Kayed R, Metherate R, Mattson MP, Akbari Y, LaFerla FM. Triple-transgenic model of Alzheimer's disease with plaques and tangles: intracellular Abeta and synaptic dysfunction. Neuron. 2003;39:409–421. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00434-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kayed R, Head E, Thompson JL, McIntire TM, Milton SC, Cotman CW, Glabe CG. Common structure of soluble amyloid oligomers implies common mechanism of pathogenesis. Science. 2003;300:486–489. doi: 10.1126/science.1079469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller Y, Ma B, Nussinov R. Synergistic interactions between repeats in tau protein and Aβ amyloids may be responsible for accelerated aggregation via polymorphic states. Biochemistry. 50:5172–5181. doi: 10.1021/bi200400u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo JP, Arai T, Miklossy J, McGeer PL. Abeta and tau form soluble complexes that may promote self aggregation of both into the insoluble forms observed in Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:1953–1958. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509386103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manczak M, Reddy PH. Abnormal interaction of VDAC1 with amyloid beta and phosphorylated tau causes mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:5131–5146. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]