Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

Intimate partner violence (IPV) during pregnancy affects 0.9% to 17% of women and affects maternal health significantly. The impact of IPV extends to the health of children, including an increased risk of complications during pregnancy and the neonatal period, mental health problems, and cognitive delays. Despite substantial sequelae, there is limited research substantiating best practices for engaging and retaining high-risk families in perinatal home visiting (HV) programs, which have been shown to improve infant development and reduce maltreatment.

METHODS:

The Domestic Violence Enhanced Home Visitation Program (DOVE) is a multistate longitudinal study testing the effectiveness of a structured IPV intervention integrated into health department perinatal HV programs. The DOVE intervention, based on an empowerment model, combined 2 evidence-based interventions: a 10-minute brochure-based IPV intervention and nurse home visitation.

RESULTS:

Across all sites, 689 referrals were received from participating health departments. A total of 339 abused pregnant women were eligible for randomization; 42 women refused, and 239 women were randomly assigned (124 DOVE; 115 usual care), resulting in a 71% recruitment rate. Retention rates from baseline included 93% at delivery, 80% at 3 months, 76% at 6 months, and 72% at 12 months.

CONCLUSIONS:

Challenges for HV programs include identifying and retaining abused pregnant women in their programs. DOVE strategies for engaging and retaining abused pregnant women should be integrated into HV programs’ federal government mandates for the appropriate identification and intervention of women and children exposed to IPV.

Keywords: intimate partner violence, home visitation, Domestic Violence Enhanced Home Visitation Program, violence during pregnancy

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a global public health issue affecting women of all demographic, ethnic, cultural, and socioeconomic backgrounds. Women of childbearing age are at the highest risk for IPV, and the majority of studies have found the prevalence of IPV during pregnancy ranging from 3.9% to 8.3%.1,2 IPV confers considerable risk to the health of the woman, and children exposed to IPV are at an elevated risk for emotional, behavioral, and cognitive problems.3,4

Given the well-documented adverse effects of IPV on both mother and child, home visiting (HV) programs have been regarded as a particularly salient strategy for high-risk families who may have difficulty engaging in other services.5–7 Indeed, the creation of the Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program (MIECHV) marked an unprecedented fiscal commitment to HV programs designed to serve at-risk children and families. A fundamental MIECHV benchmark is appropriate screening, referrals, and safety planning for families identified for the presence of IPV.

Targeted outcomes of HV programs are largely reliant on parental involvement, and research demonstrates that families with greater participation show larger benefits.8,9 A challenge confronting many HV programs is low program retention rates; thus, increasing retention rates is critical to increase the effectiveness of HV programs. Several reviews have noted low rates of program retention, with up to 51% of families leaving HV programs within 12 months10 and up to 67% of families leaving before program completion.11 Multiple determinants have been shown to influence retention rates in HV programs (eg, attributes of families, programs, and communities),5,12,13 and the presence of IPV in the home has been linked to poorer program retention rates and less response to HV support.14 This is of particular concern given the established negative sequelae of IPV for both maternal and child physical and mental health.

This article provides an overview of the Domestic Violence Enhanced Home Visitation Program (DOVE), a structured IPV intervention integrated into existing HV programs in urban and rural settings, which shows great promise in identifying and retaining abused pregnant women in perinatal HV programs.

Methods

Procedures

Human subjects approvals were obtained from all participating academic institutions (2 universities) and the rural and urban health departments (HDs). Additionally, a Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained from the National Institutes of Health.

Study Design, Setting, and Sample

The DOVE is a multistate longitudinal randomized clinical trial testing the effectiveness of a structured IPV intervention integrated into HD perinatal HV programs. The DOVE intervention, based on an empowerment model, combined 2 evidence-based interventions: a 10-minute brochure-based IPV intervention and perinatal nurse home visitation.

Participants were recruited from an urban East Coast HD, 12 rural midwestern HDs, and 1 midwestern rural Nurse Family Partnership (NFP) program. Eligible participants were English-speaking women, ≤31 weeks’ gestation, reporting abuse within the last 12 months, and currently enrolled in a perinatal HV program of a participating HD. Referrals for the study were received from the participating HDs, and the DOVE research team contacted all referred women. Women were screened for IPV using the Abuse Assessment Screen15 and the Women’s Experience with Battering Scale.16 Informed consent was obtained from all eligible women who expressed an interest in study participation. In the urban site, women were randomly assigned to either the usual care (UC) group or the DOVE intervention group. The UC group received the standard HV and IPV protocols instituted by the HDs, and the DOVE intervention group received the standard HV and IPV protocols in addition to the DOVE IPV intervention. Women in the DOVE intervention group received 3 prenatal and 3 postnatal DOVE sessions in addition to their HV protocols. In the rural sites, among the 12 county HDs participating in the study, 6 county HDs were randomly assigned to use DOVE IPV protocols and 6 counties were assigned to use the usual IPV protocol. Women participating in the NFP program and enrolled in the current study received the DOVE intervention, which was integrated into the NFP protocols as agreed to by David Olds, PhD.

Before implementation of the study’s research protocols, the principal investigators (PIs) conducted training for home visitors in all participating HDs. The 4-hour training included information about IPV, with attention to IPV during pregnancy and the importance of screening and intervening for IPV during pregnancy. The home visitors delivering the DOVE intervention attended an additional 4-hour training that included topics specific to the research protocol, use of the screening and assessment instruments, delivering the brochure-based DOVE intervention, developing an individualized safety plan for each DOVE participant, strategies for revisiting and reinforcing the safety plan at each subsequent home visit, and appropriate documentation of the DOVE intervention and other pertinent information about the visit. The format of the trainings included providing information and providing numerous opportunities for role playing in screening for IPV and implementing the DOVE intervention. Additionally, all DOVE home visitors were trained on safety protocols including necessary actions to implement if the abuser came home during the visit, how to safely engage the abuser during the home visit, and how to conclude the home visit if necessary, keeping both the mother and the home visitor safe. Over the course of the 5-year study there were annual booster training sessions for the intervention home visitors. Newly hired home visitors were trained individually. The research team also received extensive training in IPV, working with abused women, implementing the research protocol, and data collection considerations.

Results

A total of 239 women were included in the DOVE research study. The demographics of the study sample are described in Table 1. Overall, the sample was predominantly single, low-income African American or Caucasian women. The majority of women received government assistance and obtained their prenatal care in a public health clinic.

TABLE 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of DOVE Sample (N = 239)

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 24.0 (5.2) |

| Race | |

| African American | 113 (47) |

| White Non-Hispanic | 101 (42) |

| American Indian, Alaskan Native, other | 24 (10) |

| Education level | |

| <High school | 95 (41) |

| High school graduate or GED | 59 (25) |

| Some college or trade school | 54 (23) |

| College or trade school graduate | 27 (11) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 120 (51) |

| Married | 60 (25) |

| Divorced | 27 (11) |

| Widowed or other | 30 (12) |

| Employment status | |

| Unemployed | 171 (72) |

| Part-time | 38 (16) |

| Full-time | 29 (12) |

| Insurance (Medicaid) | |

| Yes | 228 (96) |

| No | 9 (4) |

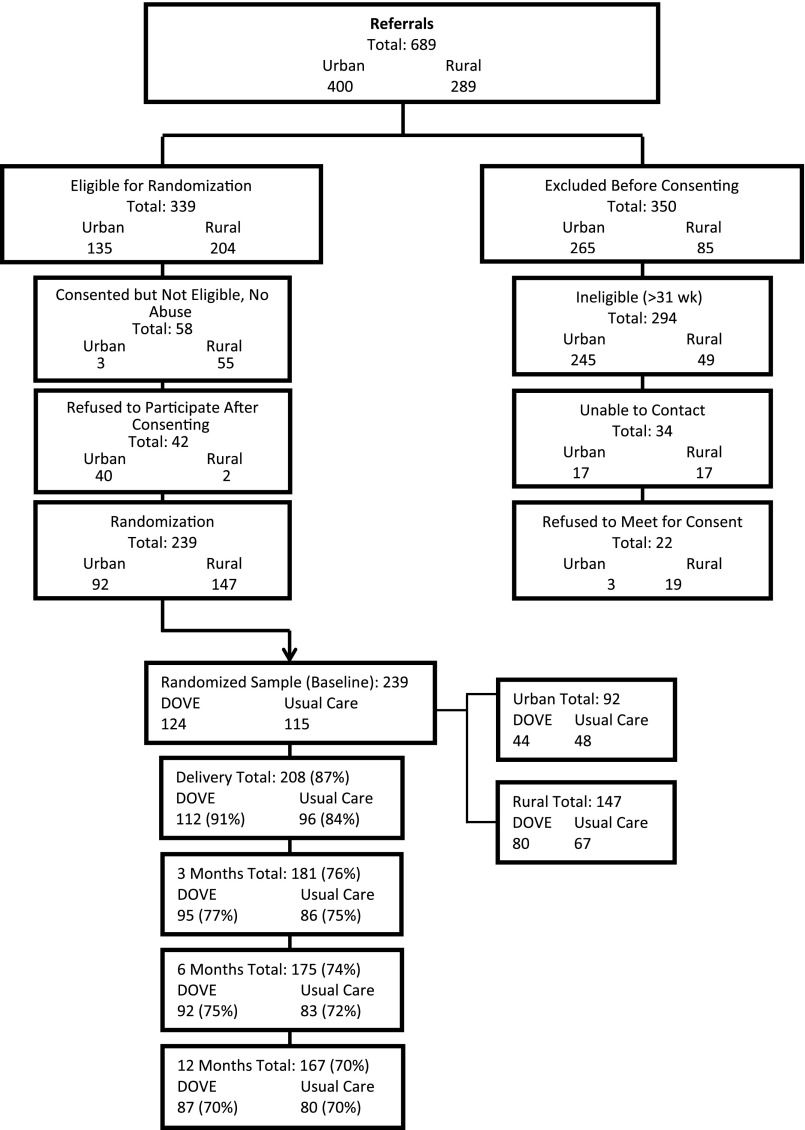

The DOVE research team received a total of 689 referrals from participating HDs. Of those referrals, 350 women were not eligible and were excluded before randomization. Among the women excluded, 294 were ineligible because they were at >31 weeks’ gestation, 34 women were lost to follow-up, and 22 women refused additional contact regarding study enrollment and consent. Of the 339 abused pregnant women who were eligible for randomization, 58 women were consented but failed to screen positive for IPV, and 42 women consented for the study but refused additional study participation resulting in 239 women who enrolled and were eligible for randomization. The final study sample included 92 women from the urban site and 147 women from the rural sites. Figure 1 provides a flow diagram of the recruitment and retention rates across urban and rural sites.

FIGURE 1.

Study recruitment and retention flow diagram.

With respect to the urban site, a total of 400 referrals were initially received from the HD. Examining only women who were eligible for randomization, 40 women refused study participation and 92 women were randomly assigned, with 44 to the DOVE intervention and 48 to the UC group.

A total of 289 referrals were received in the rural sites, with 204 women eligible for randomization. Of the 85 women excluded before randomization, 49 women were ineligible (gestation >31 weeks), 17 women were lost to follow-up, and 19 women refused additional study participation. A total of 147 women were randomly assigned, with 80 women assigned to the DOVE intervention and 67 women assigned to the UC group.

Retention rates for the entire sample from baseline were as follows: 87% of women were retained at delivery, 76% were retained at 3 months, 74% were retained at 6 months, and 70% were retained at 12 months. Of the urban sample only, 86% of women were retained at delivery, 77% were retained at 3 months, 73% were retained at 6 months, and 71% of women were retained at 12 months. Specific retention rates from baseline for rural sites indicate that 88% of women were retained at delivery, 80% were retained at 3 months, 74% were retained at 6 months, and 69% were retained at 12 months. There were no differences in retention rates for women participating in the NFP program and receiving the DOVE intervention. For the total sample, retention rates from baseline for women who received the DOVE intervention were 91% at delivery, 77% at 3 months, 75% at 6 months, and 70% of women at 12 months. Women randomly assigned to UC had retention rates as follows: 84% of women were retained at delivery, 75% were retained at 3 months, 72% were retained at 6 months, and 70% were retained at 12 months.

Discussion

The patterns of retention rates were similar when they were compared across geographic sites (urban versus rural) and group classifications (DOVE intervention versus UC). These findings suggest that many abused pregnant women who are screened for IPV will disclose their abuse histories and will remain in perinatal HV programs and research programs that specifically address IPV. Several strategies, implemented together, may increase the retention of abused women in HV programs.

The rural sites initiated recruitment in February 2007, and after 5 months of recruitment only 19 referrals had been received from 12 HV programs. Given the very low referral rates, the PI ascertained that either women were reluctant to discuss IPV with the home visitors, or the home visitor was having difficulty assessing for abuse during pregnancy. Although 4 formal training programs, consisting of at least a half-day session, had been provided to all home visitors in all 12 programs, a fifth training session was planned and implemented.17 Barriers and facilitators to screening were discussed, and the most common barriers discussed by home visitors included fear of either being a victim of violence from the abusive partner or having the client withdraw from HV because discussing IPV would be too sensitive and intrusive for participants. Thus, the study protocol was modified so that home visitors obtained only the woman’s consent to provide her name and contact information, to be given to the research team. With this modification, the research team could assess for IPV after the women consented to be in the study. This change led to a substantial increase in the number of referrals received from participating HDs. As demonstrated in Fig 1, only 58 of the 270 women screened negative for abuse. This indicates that 80% of the women referred to the study were experiencing abuse. Our findings demonstrate that >70% of women enrolled in the DOVE study were retained. This suggests that women were not afraid or unwilling to discuss their abuse histories, and were engaged in research aimed at mitigating the effects of abuse on women and children.

Similar challenges were evident in the urban setting. That is, recruitment rates were thought to be low because there were several layers of screening for IPV before referral by the HD to the research team. When the PI requested that the research nurse accompany the home visitors on each new visit to explain the study and perform the assessment for IPV, dramatic increases were noted in recruitment rates and positive IPV screens. Across both study sites, a collaborative partnership that reinforced the IPV training and role-modeled screening helped the home visitors gain confidence in screening for IPV. Our results indicate that home visitors’ confidence in screening for IPV increased with additional training and opportunities to observe health care professionals screen women for IPV and educate women on IPV. Ultimately, the goal is that home visitors will be comfortable to integrate IPV screening into a routine piece of the HV protocols.

Retaining low-income, abused women in rural and urban settings over a period of 2 years in a research study is not free of challenges. However, a committed research team that successfully collaborated with home visitors was integral to the program’s success. A routine protocol in working with abused women is to ask about their level of safety and obtain contact information for other safe contacts of the woman. Research suggests that obtaining safe contacts in addition to participant contact information improves the ability to appropriately follow up with abused women.18 Therefore, the DOVE research nurses documented a safe address and phone number for every participant during the initial interview, and in most cases women provided contact information of a close relative or friend. Research nurses also sought permission to contact the HD home visitors in the event they were not able to reach the woman or her related contacts. For many women in the study, telephone service was inconsistent because of financial strain. Thus, research nurses continually searched for updated information and routinely tried to reestablish contact through previous disconnected phone numbers. If the study team was unable to reach the participant through phone calls or mailings, the research nurse contacted the home visitors to discuss additional options for additional contact. For many women, the consistent contact with home visitors afforded the study team the greatest opportunity for contact. However, there were times when women continued in the research study but withdrew from the state’s HV program. This may in part be due to women’s comfort in engaging with the research nurses and feeling that they were able to speak about violence in their lives that had been reluctantly addressed or not addressed at all by the home visitors.

The research nurses were persistent in their attempts to retain study participants. If the research nurse was not able to contact the woman via phone, mailings, the home visitor, or additional contacts, she went to the woman’s residence without an appointment. This strategy often led to scheduling an appointment at a later date, verifying or revising contact information, or collecting data if the visit was within the appropriate time frame. However, if the participant was not home, the research nurse left a note with neutral terms such as “Women’s Health Study” to protect the participant’s privacy and safety. Other strategies to increase retention rates included sending birthday and holiday cards to every participant, which also assisted with notification of address changes. Additionally, during each visit, the research nurses gave the participants children’s books and diapers (both received as a donation) as a token of appreciation. Finally, each study participant was provided with the study’s toll-free number, which was printed on business cards and magnetized promotional materials, facilitating communication with research staff. Again, these materials did not include terms such as “intimate partner violence”; rather, they referred to women’s health during the perinatal period.

The research team, together with home visitors, met often to discuss any particular challenges in locating individual participants. Many of the home visitors were from the same communities as participants and were keenly aware of the difficulties these women faced on many levels. Thus, they could offer additional insight into developing creative strategies for engaging participants. These sessions also sustained team members’ motivation for locating hard-to-find participants and demonstrated to home visitors how important they were in promoting the health and well-being of the women and their children.

The similar retention rates across the UC and intervention group suggests that routine screening for violence may facilitate conversation about healthy and unhealthy relationships. Additionally, screening may help women understand options in a violent relationship and raise their awareness of the links between violence and other negative outcomes. Many of the women in this study did not realize violence was such a concerning issue until they were asked, at every study visit, about their relationships. One woman stated, “It [screening for violence] just made me realize how dangerous a situation I was in and how much worse it really was than I ever even realized. I knew it was a bad situation, but never realized it was that bad or how many different types of abuse I had experienced.” Screening for IPV can successfully identify survivors and may reduce violence and improve outcomes.19 Less studied is how to successfully implement screening, particularly in the home setting while ensuring both the home visitor’s and the participant’s comfort with screening. The strategies implemented in this study offer insights into how to leverage the ongoing relationships created in the HV context to safely and effectively screen for IPV.

The current study has several limitations. The sample was largely low-income rural and urban women participating in perinatal HV programs, so results may not be generalizable to women participating in other HV programs. The DOVE research team was able to contact only women who were referred by participating HDs and enrolled in the HD’s HV programs. It is possible that women enrolled in the study may not be representative of all abused women. Nonetheless, the study has several strengths. This was a longitudinal study of women abused during the perinatal period and included the women’s infants and toddlers. The collaborative efforts of the HV staff and research nurses resulted in strategies and study methods that safely maintained abused women and their children over the course of the 2-year study period. Our results indicate that abused women can be retained in HV programs, and related research studies, when screened for IPV. Screening for IPV may indicate to women that health care providers have a vested interest in their health and well-being and are able to connect them to much-needed resources.

The recently initiated federal government mandates included in the enhancements of Title 5, MIECHV, require HV programs to implement evidence-based protocols for screening and intervening for domestic violence. Specifically, the bill targets communities with high concentrations of preterm births, low birth weight infants, infant mortality, or related risk factors including domestic violence. HV programs must screen for IPV and provide necessary referrals. Our findings demonstrate that with adequate training and collaboration with local HD personnel, home visitors can feel confident in screening for IPV with the knowledge that it will not affect participant retention in HV programs. HV programs aiming for the best outcomes must implement universal screening for IPV and implement evidence-based interventions to address violence in the perinatal period. Abused women are often more difficult to successfully recruit, engage, and retain in HV programs.14 Our findings offer several strategies for assessing and intervening with abused women in collaboration with HV programs in rural and urban areas to optimize maternal and infant health outcomes.

Glossary

- DOVE

Domestic Violence Enhanced Home Visitation Program

- HD

health department

- HV

home visitation

- IPV

intimate partner violence

- MIECHV

Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program

- UC

usual care

Footnotes

Drs Sharps and Bullock conceptualized and designed the study and drafted the Methods and Discussion sections of the manuscript; Dr Alhusen assisted with the interpretation of data, drafted the outline and introduction and the Discussion section of the manuscript, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript; Dr Bhandari assisted in drafting the Discussion section; Dr Ghazarian carried out the initial analyses and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Ms Udo assisted with the initial analyses and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Dr Campbell assisted in the conceptualization and design of the study and drafted the Discussion section; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

This trial has been registered with the NINR (identifier NCT00465556).

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: All phases of this study were supported by NIH/NINR grant R01009093. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Martin SL, Mackie L, Kupper LL, Buescher PA, Moracco KE. Physical abuse of women before, during, and after pregnancy. JAMA. 2001;285(12):1581–1584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saltzman LE, Johnson CH, Gilbert BC, Goodwin MM. Physical abuse around the time of pregnancy: an examination of prevalence and risk factors in 16 states. Matern Child Health J. 2003;7(1):31–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kitzmann KM, Gaylord NK, Holt AR, Kenny ED. Child witnesses to domestic violence: a meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71(2):339–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolfe DA, Crooks CV, Lee V, McIntyre-Smith A, Jaffe PG. The effects of children’s exposure to domestic violence: a meta-analysis and critique. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2003;6(3):171–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duggan A, Windham A, McFarlane E, et al. Hawaii’s Healthy Start Program of home visiting for at-risk families: evaluation of family identification, family engagement, and service delivery. Pediatrics. 2000;105(1 pt 3):250–259 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leventhal JM. The prevention of child abuse and neglect: successfully out of the blocks. Child Abuse Negl. 2001;25(4):431–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olds DL, Henderson CR, Jr, Phelps C, Kitzman H, Hanks C. Effect of prenatal and infancy nurse home visitation on government spending. Med Care. 1993;31(2):155–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olds DL, Henderson CR, Jr, Kitzman HJ, Eckenrode JJ, Cole RE, Tatelbaum RC. Prenatal and infancy home visitation by nurses: recent findings. Future Child. 1999;9(1):44–65, 190–191 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wagner MM, Clayton SL. The Parents as Teachers program: results from two demonstrations. Future Child. 1999;9(1):91–115, 179–189 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guterman N. Stopping Child Maltreatment Before It Starts: Emerging Horizons in Early Home Visitation Services. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gomby DS, Culross PL, Behrman RE. Home visiting: recent program evaluations—analysis and recommendations. Future Child. 1999;9(1):4–26, 195–223 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCurdy K, Daro D. Parent involvement in family support programs: an integrated theory. Fam Relat. 2001;50(2):113–121 [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCurdy K, Hurvis S, Clark J. Engaging and retaining families in child abuse prevention programs. The APSAC Advisor. 1996;9(3):3–9 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eckenrode J, Ganzel B, Henderson CR, Jr, et al. Preventing child abuse and neglect with a program of nurse home visitation: the limiting effects of domestic violence. JAMA. 2000;284(11):1385–1391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soeken K, Parker B, McFarlane J, Lominak MC. The abuse assessment screen: A clinical instrument to measure frequency, severity and perpetrator of abuse against women. In: Campbell J, ed. Empowering Survivors of Abuse: Health Care for Battered Women and Their Children. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith PH, Earp JA, DeVellis R. Measuring battering: Development of the women’s Experience With Battering (WEB) scale. Womens Health. 1995;1(4):273–288 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eddy T, Kilburn E, Chang C, Bullock L, Sharps P. Facilitators and barriers for implementing home visit interventions to address intimate partner violence: town and gown partnerships. Nurs Clin North Am. 2008;43(3):419–435, ix [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sullivan CM, Rumptz MH, Campbell R, Eby KK, Davidson WS. Retaining participants in longitudinal community research: a comprehensive protocol. J Appl Behav Sci. 1996;32(3):262–276 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nelson HD, Bougatsos C, Blazina I. Screening women for intimate partner violence: a systematic review to update the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(11):796–808, W-279, W-280, W-281, W-282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]