Abstract

Objectives

To assess the predictors of time-to-lupus renal disease in Latin American patients.

Methods

SLE patients (n=1480) from GLADEL’s (Grupo Latino Americano De Estudio de Lupus) longitudinal inception cohort were studied. Endpoint was ACR renal criterion development after SLE diagnosis (prevalent cases excluded). Renal disease predictors were examined by univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression analyses. Antimalarials were considered time-dependent in alternative analyses.

Results

Of the entire cohort, 265 patients (17.9%) developed renal disease after entering the cohort. Of them, 88 (33.2%) developed persistent proteinuria, 44 (16.6%) cellular casts and 133 (50.2%) both; 233 patients (87.9%) were women; mean (± SD) age at diagnosis was 28.0 (11.9) years; 12.8% were African-Latin Americans, 52.5% Mestizos, 34.7% Caucasians (p=0.0016). Mestizo ethnicity (HR 1.61, 95% CI 1.19–2.17), hypertension (HR 3.99, 95% CI 3.02–5.26) and SLEDAI at diagnosis (HR 1.04, 95% CI 1.01–1.06) were associated with a shorter time-to-renal disease occurrence; antimalarial use (HR 0.57, 95% CI 0.43–0.77), older age at onset (HR 0.90, 95% CI 0.85–0.95, for every 5 years) and photosensitivity (HR 0.74, 95% CI 0.56–0.98) were associated with a longer time. Alternative model results were consistent with the antimalarial protective effect (HR 0.70, 95% CI 0.50–0.99).

Conclusions

Our data strongly support the fact that Mestizo patients are at increased risk of developing renal disease early while antimalarials seem to delay the appearance of this SLE manifestation. These data have important implications for the treatment of these patients regardless of their geographic location.

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence and incidence of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), as well as of renal involvement or lupus nephritis (LN) varies around the world with higher rates observed in some racial/ethnic groups including Mestizos (individuals born in Latin America who have both Amerindian and Caucasian ancestors), African Americans, Hispanics living in the continental United States (US) and Asians compared with Caucasians 1–4. Patients from some of these ethnic groups are also more likely to develop renal involvement earlier 5, and to experience less favorable outcomes 6–8. Although genetic factors are likely to be operative 9 to explain some of these findings, other factors may also account for the progression of LN to renal damage including histopathological and laboratory findings, concomitant hypertension, inadequate response to therapy and socioeconomic factors such as poverty and smoking 6, 10, 11. On the other hand, antimalarials such as hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine have been reported to have a protective effect on renal damage occurrence in lupus patients 12, 13. We have previously demonstrated in the GLADEL cohort (Grupo Latino Americano De Estudio del Lupus or Latin American Group for the Study of Lupus) that renal disease is more common in Mestizo and African descendants than in patients of Caucasian ancestry and also less common in those patients taking antimalarials than in those not taking them 14. We have now examined the factors associated with the early occurrence of LN in these Latin American lupus patients. We hypothesize that patients of Mestizo background are at increased risk of developing LN early while antimalarial medications will retard its occurrence.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

GLADEL is an observational inception cohort started in 1997 to study the socio-demographic, clinical and treatment characteristics of Latin American lupus patients. This cohort comprises 34 centers with experience in SLE (tertiary referral centers with a lupus clinic, an academic profile and a rheumatology training program); a genuine interest in the research project; the presence of an identified leader; and adequate human, technical and communication facilities. These centers are distributed among nine Latin American countries and each one follows a common protocol with consensus definitions and outcome measures that have been described in detail, elsewhere; diagnostic procedures and treatment decisions are, however, made by the treating physicians and not by protocol 3. Institutional review boards’ local regulations were followed at all centers. All data were collected into the ARTHROS database (a user-friendly database developed by Argentinean rheumatologists using a Windows platform, Visual Basic language and Microsoft Access). Data were submitted via Internet to the coordinating center where they were reviewed to ensure their quality.

The cohort is currently comprised of 1480 patients of different ethnic background (Mestizo, African-Latin American, Caucasian and Other). The diagnosis of SLE was based on the clinical and laboratory features present and the expertise of the investigator (rheumatologist or qualified internist with experience in SLE). Fulfillment of four American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 1982 SLE criteria 15, 16 at the time of diagnosis was not mandatory. Also, disease diagnosis could occur subsequently to a patient accruing at least four ACR criteria. Time of fulfillment of each criterion was identified as well as the time of SLE diagnosis.

Variables

The end point of this study, renal disease, was defined by the respective ACR renal criterion [persistent proteinuria (greater than 0.5 grams per day or greater than 3+ if quantitation not performed) or the presence of cellular casts (that may be red cell, hemoglobin, granular, tubular, or mixed)]. Independent variables considered for this study included socio-demographic characteristics, clinical manifestations, ACR classification criteria, disease activity score and medications used. These variables have been assessed up to the time of disease diagnosis which will be considered as baseline characteristics for this study.

Disease activity was ascertained with the SLE Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI) 17 at diagnosis and every six months thereafter and was used as a continuous variable. Exposure to medications was dichotomized according to their use or nonuse.

Statistical analyses

From the entire GLADEL cohort (n= 1480 patients), 535 were excluded from this analysis; 498 of them because renal disease occurred prior entering into the cohort and 37 because they were from other ethnic groups. The remaining 945 patients free of renal disease at diagnosis in the context of this longitudinal observational cohort study were included in the analysis. Baseline disease and patient characteristics as listed above were examined descriptively as a function of time-to-renal disease occurrence. Variables significant at p ≤ 0.10 were included into a time-to-the event analysis using Cox proportional hazards regression model; however, in this model the two immunological variables (immunologic disorder and antinuclear antibodies) within the chosen cut-off point were omitted to preserve the sample size. Using a stepwise procedure, a reduced or parsimonious model was subsequently obtained. Results are expressed as hazard ratios (HRs), with their corresponding 95% CIs. HRs >1 indicate a shorter time-to-the event (renal disease), while values <1 indicate a longer time. In an alternative multivariable model antimalarial use was considered a time-dependent variable and the data were then re-examined. Use was defined as the intake of antimalarials for at least three months and not use, otherwise. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS software, version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Among the 945 patients included in this study 265 (17.9%) developed renal disease after entering the cohort. Eighty-eight patients (33.2%) developed persistent proteinuria and 44 (16.6%) cellular casts; 133 patients (50.2%) developed both. Two hundred and thirty-three of the cases (87.9%) were women; their mean (± SD) age at diagnosis was 28.0 (11.9) years and their median follow up time [Q3-Q1 interquartile range] was 57.1 months [Q3–Q1: 46.4]. All three ethnic groups were represented in the study population, but Mestizos (65.4%) and African Latin Americans (70.4%) were more likely to develop renal disease than the Caucasians (21.5%). Renal biopsies were performed in 84 (31.7%) of the cases with 15 (15.5%) being class II World Health Organization (WHO) LN, 15 (15.5%) class III, 47 (48.4%) class IV and 9 (9.3%) class V, while 11 (11.3%) presented tubulointerstitial and vascular disease. Of the patients receiving antimalarials at diagnosis, 31.1% went on to develop renal disease while 68.9% did not; for the antihypertensive drugs these figures were 66.1% and 33.9%, respectively; for glucocorticoids pulses they were 57.8% and 42.2%; for low dose glucocorticoids they were (≤20mg) 22.3% and 77.7%; for medium dose glucocorticoids (>20 – <60 mg) they were 39.7% and 60.2%; for high dose (≥60mg) glucocorticoids they were 38.0% and 62.0%; for azathioprine use they were 59.4% and 40.6% and for cyclophosphamide they were 11.0% and 89.0%.

Univariable analyses

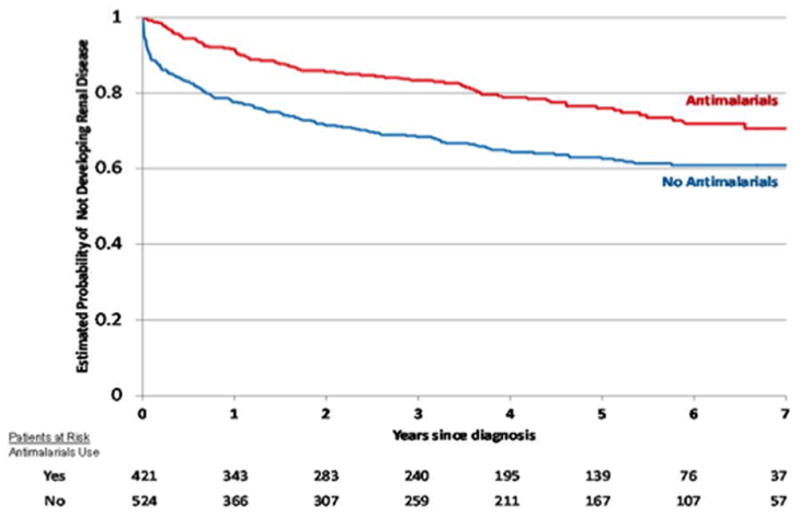

Table 1 shows the results of the univariable time-to-renal disease analysis. From the socioeconomic/demographic domains baseline variables associated with a longer time-to-renal disease were: female gender, older age at disease diagnosis and at onset; in contrast, fewer years of education, Mestizo and African-Latin American ethnicity, rural residency and low socioeconomic status associated with a shorter time-to-renal disease. Within the clinical features, disease activity at diagnosis as measured by the SLEDAI, the presence of a comorbid condition such as hypertension and the presence of immunologic disorder associated with a shorter time-to-renal disease; on the other hand, some ACR criteria such as: discoid rash, photosensitivity and antinuclear antibodies associated with a longer time-to-renal disease. As for the treatment variables, antihypertensive drugs and pulses of glucocorticorticoids were found to be associated with a shorter time-to-renal disease occurrence; in contrast, antimalarial use, and a lower dose of glucocorticosteroids (≤20mg) associated with a longer time-to-renal disease occurrence. The estimated cumulative probability of developing renal disease within five years of diagnosis was 37% for patients not taking antimalarials and 24% for those who received antimalarials on or before diagnosis (log-rank test P<0.0001). The corresponding Kaplan-Meier survival curve is depicted in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Socioeconomic-demographic, clinical, serologic and treatment variables associated with time-to-renal disease* occurrence in GLADEL patients by univariable Cox proportional hazards regression analyses.

| Feature | Time-to-renal disease | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Present (n: 265) | Absent (n: 680) | HR (95%CI) | |

| Gender, female | 233 (87.9) | 628 (92.4) | 0.64 (0.44–0.93) |

| Age at disease onset, years, mean (SD) | 26.6 (11.5) | 29.3 (12.6) | 0.93 (0.88–0.98) |

| Age at diagnosis, years, mean (SD) | 28.0 (11.9) | 31.0 (12.7) | 0.92 (0.87–0.97) |

| Ethnic group, % | |||

| Caucasian (92/249) | 92 (34.7) | 336 (49.4) | reference group |

| Mestizo (139/210) | 139 (52.5) | 263 (38.7) | 1.80 (1.39–2.35) |

| African-Latin American (34/71) | 34 (12.8) | 81 (11.9) | 1.66 (1.12–2.46) |

| Residence, rural, % | 25 (9.5) | 39 (5.8) | 1.67 (1.11–2.52) |

| Socioeconomic status, % | |||

| Upper/upper-middle | 19 (7.2) | 96 (14.1) | reference group |

| Middle | 68 (25.7) | 209 (30.8) | 1.50 (0.90–2.50) |

| Lower-middle/lower | 178 (67.2) | 374 (55.1) | 2.11 (1.31–3.38) |

| Education, years, % | |||

| More than 12 | 59 (22.3) | 191 (28.1) | reference group |

| 8–12 | 122 (46.0) | 303 (44.6) | 1.15 (0.84–1.57) |

| 0–7 | 84 (31.7) | 186 (27.4) | 1.37 (0.98–1.91) |

| Medical insurance, % | |||

| Without coverage | 40 (15.2) | 116 (17.3) | reference group |

| Partial coverage | 61 (23.2) | 122 (18.2) | 1.28 (0.86–1.91) |

| Full coverage | 162 (61.6) | 434 (64.6) | 0.99 (0.70–1.41) |

| Diabetes, % | 2 (0.8) | 5 (0.7) | 1.41 (0.53–3.79) |

| Hypertension, % | 52 (19.6) | 113 (16.6) | 3.78 (2.97–4.81) |

| ACR Criteria, % | |||

| Malar rash | 162 (61.1) | 371 (54.6) | 0.87 (0.68–1.11) |

| Discoid rash | 24 (9.1) | 92 (13.5) | 0.47 (0.29–0.78) |

| Photosensitivity | 133 (50.2) | 383 (56.3) | 0.65 (0.51–0.82) |

| Oral Ulcers | 119 (44.9) | 222 (32.7) | 1.07 (0.83–1.38) |

| Arthritis | 228 (86.0) | 515 (75.7) | 1.16(0.86–1.56) |

| Serositis | 84 (31.7) | 103 (15.2) | 1.25(0.92–1.71) |

| Neurologic disorder | 24 (9.1) | 51 (7.5) | 0.77(0.46–1.30) |

| Hematologic disorder | 197 (74.3) | 360 (52.9) | 0.95 (0.74–1.20) |

| Immunologic disorder | 180 (67.9) | 347 (71.6) | 1.51(1.02–2.24) |

| Antinuclear antibodies | 229 (86.4) | 575 (98.0) | 0.47 (0.24–0.92) |

| SLEDAI at diagnosis, mean (SD) | 11.0 (6.4) | 9.35 (5.8) | 1.05 (1.02–1.07) |

| Medications, % | |||

| Antihypertensive drugs | 41 (15.5) | 21 (3.1) | 1.86 (1.06–3.24) |

| Antimalarials † | 150 (56.6) | 333 (49.0) | 0.56 (0.43–0.72) |

| Azathioprine | 41 (15.5) | 28 (4.1) | 0.55(0.25–1.24) |

| Glucocorticoid dose, pulse | 37 (14.0) | 27 (4.0) | 1.65 (1.02–2.66) |

| Glucocorticoid dose, oral‡ | |||

| Low (≤20mg) | 58 (21.9) | 202 (29.7) | 0.61 (0.44–0.85) |

| Medium (>20 – <60 mg) | 89 (33.6) | 135 (19.9) | 0.90 (0.65–1.23) |

| High (≥60mg) | 62 (23.4) | 101 (14.9) | 0.84 (0.59–1.20) |

| Cyclophosphamide use | 25 (9.4) | 202 (29.7) | 1.39 (0.57–3.36) |

Renal disease was determined by the ACR criterion (persistent proteinuria and/or cellular casts).

Antimalarial agent (chloroquine and/or hydroxychloroquine).

Weighted dose of steroids. HR = hazard ratio; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval.

Figure 1.

Cumulative probability of not developing renal disease in GLADEL (Grupo Latino Americano De Estudio de Lupus) as a function of antimalarial intake by Kaplan-Meier survival analyses.

Multivariable analyses

The results of the multivariable analysis with the corresponding HRs and 95% CIs are shown in Table 2. In the final (reduced or parsimonious) model Mestizo ethnicity (HR 1.61, 95% CI 1.19–2.17), hypertension (HR 3.99, 95% CI 3.02–5.26) and disease activity as measured by the SLEDAI at diagnosis (HR 1.04, 95% CI 1.01–1.06) were associated with a shorter time-to-renal disease, whereas the use of antimalarials (HR 0.57, 95% CI 0.43–0.77), older age at disease onset (HR 0.90, 95% CI 0.85–0.95, for every 5 years) and photosensitivity (HR 0.74, 95% CI 0.56–0.98) were associated with a longer time. In the alternative model the protective effect of antimalarials was still evident although the HR was somewhat higher (0.70, 95% CI 0.50–0.99).

Table 2.

Multivariable Cox proportional hazard model: time-to-renal disease *

| Features | Full Model | Reduced Model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | |

| Gender, Female | 0.80 | 0.52–1.23 | ||

| Age at disease onset† | 0.91 | 0.85–0.96 | 0.90 | 0.85–0.95 |

| Ethnic group | ||||

| Caucasian | reference group | |||

| Mestizo | 1.55 | 1.13–2.13 | 1.61 | 1.19–2.17 |

| African-Latin American | 1.47 | 0.94–2.29 | 1.35 | 0.88–2.07 |

| Residence | ||||

| Urban | reference group | |||

| Rural | 1.17 | 0.71–1.92 | ||

| Socioeconomic Status | ||||

| Upper/upper-middle | reference group | |||

| Middle | 1.67 | 0.91–3.08 | ||

| Lower-middle/lower | 1.68 | 0.92–3.05 | ||

| Education, years | ||||

| More than 12 | reference group | |||

| 8–12 | 0.98 | 0.66–1.45 | ||

| 0–7 | 0.93 | 0.60–1.46 | ||

| Hypertension | 3.96 | 2.97–5.30 | 3.99 | 3.02–5.26 |

| Discoid rash | 0.59 | 0.35–1.00 | ||

| Photosensitivity | 0.76 | 0.57–1.01 | 0.74 | 0.56–0.98 |

| SLEDAI score at diagnosis | 1.04 | 1.01–1.06 | 1.04 | 1.01–1.06 |

| Antimalarial use | 0.65 | 0.47–0.90 | 0.57 | 0.43–0.77 |

| Glucocorticoid dose, pulse | 1.04 | 0.58–1.89 | ||

| Glucocorticoid dose, oral | ||||

| No | reference group | |||

| Low (≤20mg/day) | 0.74 | 0.49–1.10 | ||

| Medium (>20–<60 mg/day) | 0.84 | 0.58–1.22 | ||

| High (≥60mg/day) | 0.69 | 0.44–1.07 | ||

See Table 1 for additional definitions.

For every 5 years.

We also examined whether accruing four ACR criteria was associated with the use of antimalarials but that was not the case as the proportion of patients who accrued four ACR criteria was comparable in those who received antimalarials and those that did not (xx96% vs. 94yy%, the ACR criteria The likelihood of (X2 = 2.03; p=0.1537). Not surprisingly, however, the likelihood of developing renal disease as per the ACR classification criteria was lower in those patients who did not meet four ACR classification criteria vs. those who fulfilled them. (23 vs. 54%; X2 = 23.49; p <0.0001).

DISCUSSION

We have studied for the first time the factors which predict the early occurrence of renal disease in SLE patients from the largest Latin American SLE cohort. We have shown in multivariable time-dependent analyses that Mestizo patients are at increased risk of developing renal disease earlier than patients from other ethnics groups. These findings should alert Latin American physicians and others around the world were these patients may have relocated about the possible early occurrence of renal disease among them, and recognize it accordingly. The more frequent and early occurrence of renal disease in Latin American Mestizo patients is consistent with the data from the LUMINA cohort in which Hispanic patients of predominant Amerindian ancestry experienced renal disease frequently and early. Previous studies have shown that non-Caucasian ethnic ancestry is an important predictor of renal disease in SLE 1, 2, 4, 5, 18–24; it is important to point out that in comparison to these studies, patients in the GLADEL cohort include not only patients from North and Central America but also from South America. While some of the poor outcomes observed in patients with lupus from ethnic minority groups are no longer evident in multivariable analyses in which socioeconomic factors are included 6, 7, that is not the case with time-to-renal disease; the effect of Mestizo ethnicity in our study persisted even after adjusting for socioeconomic status and education. These findings highlight the very important role of genetic factors in the ethnicity-dependent susceptibility to renal involvement. Sanchez et al. have demonstrated an increase of 2.34 SLE risk alleles in subjects with 100% Amerindian ancestry as compared with subjects with 0% of such ancestry, and that an individual with a 43% higher Amerindian ancestry would have, on average, 1 additional SLE risk allele 25. On the other hand, Richman et al. found that a 10% increase in the proportion of ancestral European genes was associated with a 15% reduction in the odds of having renal disease, after adjustment for disease duration and sex 26. Future studies to identify genes of Amerindian origin that contribute to the increased risk of renal disease are clearly needed.

In this study we have also shown for the first time, and after adjusting for potential confounding variables, that the use of antimalarials whether at diagnosis, or examined as a time-dependent variable retards the development of renal disease in lupus patients. We are cognizant of the fact that patients with milder disease or who had not met four ACR classification criteria at enrolment or who were also receiving lower doses of glucocorticoids were more likely to receive antimalarials than their counterparts; in other words, there was confounding by indication. These variables, however, were included in the multivariable analyses so these assertions cannot be supported with the data presented; others may argue that propensity score analyses should have been performed but there are experts in the field who strongly believe that adjusting for the individual variables achieve the same results 27. The data on the protective effect of antimalarials on renal disease development reinforce a new paradigm that has been driven from different observational cohort studies were patients treated with these compounds experience either less frequent serious organ involvement or a delay in their occurrence than those not treated with them. Five such studies have been published. Firstly, Siso et al. showed that exposure to antimalarials before the diagnosis of LN was negatively associated with the development of renal failure, hypertension, thrombosis and infection, and with a better survival rate at the end of follow-up 12. Secondly, Kasitanon et al. demonstrated that when hydroxychloroquine was added to a regimen with mycophenolate mofetil for the treatment of membranous LN, renal remission was more frequently achieved 28. Thirdly, Baber et al. reported that those patients with LN who achieved renal remission were more likely to be on hydroxychloroquine used as an adjuvant treatment when compared with those patients not using it (93.8% versus 52.6%, p ≤ 0.010) 29. Fourthly, Pons-Estel et al. showed that after adjusting for confounding factors for the indication of hydroxychloroquine use, this drug retards the development of renal damage in patients with established LN 13. Finally, we have demonstrated, also after adjusting for confounding by indication, a clear protective effect of these compounds in the development of renal disease (ACR criteria) in SLE patients from this cohort 14; we have now gone one step further by demonstrating not only that renal disease is less common in patients taking these compounds but also that they retard the onset of renal disease in those who go on to develop it, despite their intake. So these data nicely complement all previously published observations including ours. These effects can be explained by the numerous immunoregulatory properties of antimalarials. After entering the lysosomes and raising the cell pH, antimalarials produce inhibition of toll-like receptors, reduction in the activity of lymphocytes, natural killer and plasma cells with the consequent decrease in the production of autoantibodies; they also have a negative effect in the production of interferon, TNF and IL-1 and IL-6. These properties may explain the clinical protective effect of antimalarials on the kidney and other organ systems 30–32. In the present study, younger age, high levels of disease activity and hypertension were also associated with shorter time-to-renal disease, in line with data coming from other studies 1, 18, 33–35. Although it can be argued that hypertension is not a true predictor but rather a marker of renal disease, one must not forget that the use of steroids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may have contributed to its presence. In short, physicians treating SLE patients should make every possible effort to control disease activity and comorbid conditions if renal disease is to be prevented.

This study has a number of limitations. Firstly, we could not include the prevalent cases of renal disease in our analyses since the exact temporal relationship between our endpoint and antimalarial use could not be inferred from the data collected, this could have biased the results in either direction. However given the magnitude of the HR it is unlikely that the beneficial effect would have completely abrogated or even flipped with the inclusion of these cases. Secondly, we were unable to examine the exact dose and exposure time required for antimalarials to exert their protective effect, although the average dose of antimalarials was comparable in those who developed and those who did not develop renal disease (400 mg). Thirdly, we were unable to include histopathological information in our analyses as only one third of the cases had had renal biopsies (including this variable may have reduced considerably the sample size). As noted in the Methods section, patients in the GLADEL cohort were not followed according to a standardized protocol; thus obtaining renal biopsies in patients with renal involvement among all 34 GLADEL centers was done at this discretion of the treating physician which probably account for the relatively low rate of renal biopsies; unfortunately, such data cannot be obtained now. Fourthly, we used an operational self-reported definition for ethnicity (determined according to the parents’ and all four grandparents’ ethnic origin), which may have resulted in some misclassification; however, in the final assignment the anthropomorphic characteristics of the patients were also considered. Finally, some clinically and laboratory data were not homogeneously collected and for the purpose of this study were excluded; this lack of homogeneity may also partially explain why ANA positivity appeared to be associated with a longer time to renal disease occurrence, which from the clinical point of view is certainly hard to support and even counterintuitive.

In summary, after studying the largest Latin American longitudinal cohort of patients with SLE for predictors of time-to-renal disease, we have determined that Mestizo patients are at an increased risk of developing renal involvement earlier in the course of the disease while the use of antimalarials retards the onset of this manifestation in all patients from this Latin American cohort. These data confirm racial and ethnic disparities in the occurrence of renal disease and support the beneficial effects of antimalarials regarding this manifestation in the treatment of all patients with SLE. This information is important for patients and providers in Latin America and beyond.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Daniel Villalba and Leonardo Grasso for providing expert assistance with the ARTHROS (version 6.0) software.

Supported by grants from the Federico Wilhelm Agricola Foundation Research (BAPE) and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases P01 AR49084 (GSA), and by the STELLAR (Supporting Training Efforts in Lupus for Latin American Rheumatologists) Program funded by Rheuminations, Inc (GPE and PIB) and the Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS)-Beca de Formació i Contractació de Personal Investigador (GPE). Research grant financed by FONDECYT #1110395 (PIB).

APPENDIX A. MEMBERS OF THE GLADEL STUDY GROUP

In addition to the authors, the following individuals are members of the GLADEL Study Group and have incorporated at least 20 patients into the database: from Argentina, Enrique R. Soriano, María Flavia Ceballos Recalde and Edson Velozo (Medical Clinic Service, Hospital Italiano and Fundación Dr. Pedro M. Catoggio para el Progreso de la Reumatología, Buenos Aires); Jorge A. Manni and Sebastián Grimaudo (Instituto de Investigaciones Médicas “Alfredo Lanari,” Buenos Aires); José A. Maldonado-Cocco, María S. Arriola and Graciela Gómez (Instituto de Rehabilitación Psicofísica, Buenos Aires); Mercedes A. García, Ana Inés Marcos and Juan Carlos Marcos (Hospital Interzonal General de Agudos “General San Martín,” La Plata); Hugo R. Scherbarth, Jorge A. López and Estela L. Motta (Hospital Interzonal General de Agudos “Dr. Oscar Alende,” Mar del Plata); Cristina Drenkard, Susana Gamron, Laura Onetti and Sandra Buliubasich (Hospital Nacional de Clínicas, Córdoba); Francisco Caeiro and Veronica Saurit (Hospital Privado, Centro Médico de Córdoba, Córdoba); Silvana Gentiletti, Norberto Quagliatto, Alberto A. Gentiletti and Daniel Machado (Hospital Provincial de Rosario, Rosario); Marcelo Abdala and Simón Palatnik (Universidad Nacional de Rosario, Hospital Provincial del Centenario, Rosario); Guillermo A. Berbotto and Carlos A. Battagliotti (Hospital Escuela “Eva Perón,” Granadero Baigorria, Rosario); from Brazil, Eloisa Bonfa, Eduardo F. Borba and Samuel K. Shinjo (Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo; Emilia I. Sato and Alexandre Wagner S. Souza (Universidade Federal de São Paulo); Manoel Barros Bertolo and Ibsen Bellini Coimbra (Faculdade de Ciências Médicas, Universidade Estadual de Campinas); João C. Tavares Brenol, Ricardo Xavier and Tamara Mucenic (Hospital das Clinicas de Porto Alegre, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul); Fernando Cavalcanti, Ângela Luzia Branco Duarte and Claudia Diniz Lopes Marques (Centro de Ciências da Saúde, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco); Ana Carolina de O. e Silva and Tatiana Ferracine Pacheco (Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade Federal de Goiás, Goiânia); from Colombia, José Fernando Molina-Restrepo (Hospital Pablo Tobon, Uribe), Javier Molina-López, Luis A. Ramirez Gómez and Oscar Uribe (Universidad de Antioquia, Hospital Universitario “San Vicente de Paul,” Medellín); Antonio Iglesias-Rodríguez (Universidad del Bosque, Bogotá), Eduardo Egea-Bermejo (Universidad del Norte, Barranquilla); Renato A. Guzmán-Moreno and José F. Restrepo-Suárez (Clínica Saludcoop 104 Jorge Piñeros Corpas and Hospital San Juan de Dios, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá); from Cuba, Marlene Guibert-Toledano, Gil Alberto Reyes-Llerena and Alfredo Hernández-Martínez (Centro de Investigaciones Médico Quirúrgicas, Havana); from Chile, Sergio Jacobelli (Escuela de Medicina, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago); Oscar J. Neira and Leonardo R. Guzmán (Hospital del Salvador, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad de Chile, Santiago); from Guatemala, Abraham García-Kutzbach, Claudia Castellanos and Erwin Cajas (Hospital Universitario Esperanza, Ciudad de Guatemala); from Mexico, Virginia Pascual-Ramos (Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición “Salvador Zubirán,” Mexico Distrito Federal); Leonor A. Barile-Fabris (Hospital de Especialidades Centro Médico Nacional Siglo XXI, Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, Mexico Distrito Federal, Mexico); Mary-Carmen Amigo and Luis H. Silveira (Instituto Nacional de Cardiología “Ignacio Chávez,” Mexico Distrito Federal); Ignacio García de la Torre, Gerardo Orozco-Barocio and Magali L. Estrada-Contreras (Hospital General de Occidente de la Secretaría de Salud, Guadalajara, Jalisco); María J. Sauza del Pozo, Laura E. Aranda Baca and Adelfia Urenda Quezada (Instituto Mexicano de Seguro Social, Hospital de Especialidades No 25, Monterrey, Nuevo León); from Peru, Eduardo M. Acevedo-Vázquez and Jorge M. Cucho-Venegas (Hospital Nacional “Guillermo Almenara Irigoyen,” Essalud, Lima); Cecilia P. Chung, and Magaly Alva-Linares (Hospital Nacional “Edgardo Rebagliatti Martins,” Essalud, Lima); from Venezuela, Rosa Chacón-Díaz, Neriza Rangel and Soham Al Snih Al Snih (Hospital Universitario de Caracas); Maria H. Esteva-Spinetti and Jorge Vivas (Hospital Central de San Cristóbal).

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors were involved in drafting or revising this article critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be published. Dr. Bernardo A. Pons-Estel had full access to all of the data from the study and takes responsibility for their integrity and the accuracy of the analyses performed.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- 1.Bastian HM, Roseman JM, McGwin G, Jr, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in three ethnic groups. XII. Risk factors for lupus nephritis after diagnosis. Lupus. 2002;11:152–60. doi: 10.1191/0961203302lu158oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petri M, Perez-Gutthann S, Longenecker JC, Hochberg M. Morbidity of systemic lupus erythematosus: role of race and socioeconomic status. Am J Med. 1991;91:345–53. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(91)90151-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pons-Estel BA, Catoggio LJ, Cardiel MH, et al. The GLADEL multinational Latin American prospective inception cohort of 1,214 patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: ethnic and disease heterogeneity among “Hispanics”. Medicine (Baltimore) 2004;83:1–17. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000104742.42401.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seligman VA, Lum RF, Olson JL, Li H, Criswell LA. Demographic differences in the development of lupus nephritis: a retrospective analysis. Am J Med. 2002;112:726–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burgos PI, McGwin G, Jr, Pons-Estel GJ, Reveille JD, Alarcon GS, Vila LM. US patients of Hispanic and African ancestry develop lupus nephritis early in the disease course: data from LUMINA, a multiethnic US cohort (LUMINA LXXIV) Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:393–4. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.131482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barr RG, Seliger S, Appel GB, et al. Prognosis in proliferative lupus nephritis: the role of socio-economic status and race/ethnicity. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18:2039–46. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ward MM, Pyun E, Studenski S. Long-term survival in systemic lupus erythematosus. Patient characteristics associated with poorer outcomes. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:274–83. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Danila MI, Pons-Estel GJ, Zhang J, Vila LM, Reveille JD, Alarcon GS. Renal damage is the most important predictor of mortality within the damage index: data from LUMINA LXIV, a multiethnic US cohort. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48:542–5. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alarcon GS, Bastian HM, Beasley TM, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in a multi-ethnic cohort (LUMINA) XXXII: [corrected] contributions of admixture and socioeconomic status to renal involvement. Lupus. 2006;15:26–31. doi: 10.1191/0961203306lu2260oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goulet JR, MacKenzie T, Levinton C, Hayslett JP, Ciampi A, Esdaile JM. The longterm prognosis of lupus nephritis: the impact of disease activity. J Rheumatol. 1993;20:59–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petri M. Hopkins Lupus Cohort. 1999 update. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2000;26:199–213. v. doi: 10.1016/s0889-857x(05)70135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siso A, Ramos-Casals M, Bove A, et al. Previous antimalarial therapy in patients diagnosed with lupus nephritis: influence on outcomes and survival. Lupus. 2008;17:281–8. doi: 10.1177/0961203307086503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pons-Estel GJ, Alarcon GS, McGwin G, Jr, et al. Protective effect of hydroxychloroquine on renal damage in patients with lupus nephritis: LXV, data from a multiethnic US cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:830–9. doi: 10.1002/art.24538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pons-Estel GJ, Alarcon GS, Hachuel L, et al. Anti-malarials exert a protective effect while Mestizo patients are at increased risk of developing SLE renal disease: data from a Latin-American cohort. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012;51:1293–8. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1725. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries JF, et al. The 1982 revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1982;25:1271–7. doi: 10.1002/art.1780251101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bombardier C, Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, Caron D, Chang CH. Derivation of the SLEDAI. A disease activity index for lupus patients. The Committee on Prognosis Studies in SLE. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:630–40. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bastian HM, Alarcon GS, Roseman JM, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in a multiethnic US cohort (LUMINA) XL II: factors predictive of new or worsening proteinuria. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:683–9. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adler M, Chambers S, Edwards C, Neild G, Isenberg D. An assessment of renal failure in an SLE cohort with special reference to ethnicity, over a 25-year period. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;45:1144–7. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alarcon GS, McGwin G, Jr, Petri M, Reveille JD, Ramsey-Goldman R, Kimberly RP. Baseline characteristics of a multiethnic lupus cohort: PROFILE. Lupus. 2002;11:95–101. doi: 10.1191/0961203302lu155oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hopkinson ND, Jenkinson C, Muir KR, Doherty M, Powell RJ. Racial group, socioeconomic status, and the development of persistent proteinuria in systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2000;59:116–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.59.2.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Korbet SM, Schwartz MM, Evans J, Lewis EJ. Severe lupus nephritis: racial differences in presentation and outcome. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:244–54. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006090992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Contreras G, Lenz O, Pardo V, et al. Outcomes in African Americans and Hispanics with lupus nephritis. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1846–51. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peschken CA, Katz SJ, Silverman E, et al. The 1000 Canadian faces of lupus: determinants of disease outcome in a large multiethnic cohort. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:1200–8. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sanchez E, Rasmussen A, Riba L, et al. Impact of genetic ancestry and sociodemographic status on the clinical expression of systemic lupus erythematosus in American Indian-European populations. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:3687–94. doi: 10.1002/art.34650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richman IB, Taylor KE, Chung SA, et al. European genetic ancestry is associated with a decreased risk of lupus nephritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:3374–82. doi: 10.1002/art.34567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sturmer T, Joshi M, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, Rothman KJ, Schneeweiss S. A review of the application of propensity score methods yielded increasing use, advantages in specific settings, but not substantially different estimates compared with conventional multivariable methods. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59:437–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kasitanon N, Fine DM, Haas M, Magder LS, Petri M. Hydroxychloroquine use predicts complete renal remission within 12 months among patients treated with mycophenolate mofetil therapy for membranous lupus nephritis. Lupus. 2006;15:366–70. doi: 10.1191/0961203306lu2313oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barber CE, Geldenhuys L, Hanly JG. Sustained remission of lupus nephritis. Lupus. 2006;15:94–101. doi: 10.1191/0961203306lu2271oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karres I, Kremer JP, Dietl I, Steckholzer U, Jochum M, Ertel W. Chloroquine inhibits proinflammatory cytokine release into human whole blood. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:R1058–64. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.274.4.R1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kyburz D, Brentano F, Gay S. Mode of action of hydroxychloroquine in RA-evidence of an inhibitory effect on toll-like receptor signaling. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2006;2:458–9. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wallace DJ, Gudsoorkar VS, Weisman MH, Venuturupalli SR. New insights into mechanisms of therapeutic effects of antimalarial agents in SLE. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2012;8:522–33. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2012.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anaya JM, Uribe M, Perez A, et al. Clinical and immunological factors associated with lupus nephritis in patients from northwestern Colombia. Biomedica. 2003;23:293–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Contreras G, Pardo V, Cely C, et al. Factors associated with poor outcomes in patients with lupus nephritis. Lupus. 2005;14:890–5. doi: 10.1191/0961203305lu2238oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ayodele OE, Okpechi IG, Swanepoel CR. Predictors of poor renal outcome in patients with biopsy-proven lupus nephritis. Nephrology (Carlton) 2010;15:482–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2010.01290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]