Abstract

Background

Polyoxypeptin A was isolated from a culture broth of Streptomyces sp. MK498-98 F14, which has a potent apoptosis-inducing activity towards human pancreatic carcinoma AsPC-1 cells. Structurally, polyoxypeptin A is composed of a C15 acyl side chain and a nineteen-membered cyclodepsipeptide core that consists of six unusual nonproteinogenic amino acid residues (N-hydroxyvaline, 3-hydroxy-3-methylproline, 5-hydroxypiperazic acid, N-hydroxyalanine, piperazic acid, and 3-hydroxyleucine) at high oxidation states.

Results

A gene cluster containing 37 open reading frames (ORFs) has been sequenced and analyzed for the biosynthesis of polyoxypeptin A. We constructed 12 specific gene inactivation mutants, most of which abolished the production of polyoxypeptin A and only ΔplyM mutant accumulated a dehydroxylated analogue polyoxypeptin B. Based on bioinformatics analysis and genetic data, we proposed the biosynthetic pathway of polyoxypeptin A and biosynthetic models of six unusual amino acid building blocks and a PKS extender unit.

Conclusions

The identified gene cluster and proposed pathway for the biosynthesis of polyoxypeptin A will pave a way to understand the biosynthetic mechanism of the azinothricin family natural products and provide opportunities to apply combinatorial biosynthesis strategy to create more useful compounds.

Keywords: Biosynthesis, Polyoxypeptin A, Polyketide, Nonribosomal peptide, Apoptosis-inducing activity

Background

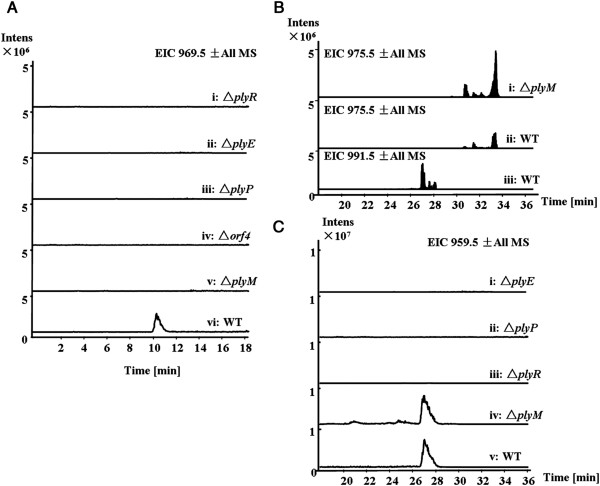

Polyoxypeptin A (PLYA) was isolated from the culture broth of Streptomyces sp. MK498-98 F14, along with a deoxy derivative named as polyoxypeptin B (PLYB), as a result of screening microbial culture extracts for apoptosis inducer of the human pancreatic adenocarcinoma AsPC-1 cells that are highly apoptosis-resistant [1,2]. PLYA is composed of an acyl side chain and a cyclic hexadepsipeptide core that features two piperazic acid units (Figure 1). Structurally similar compounds have been identified from actinomycetes including A83586C [3], aurantimycins [4], azinothricin [5], citropeptin [6], diperamycin [7], kettapeptin [8], IC101 [9], L-156,602 [10], pipalamycin [11], and variapeptin [12] (Figure 1). This group of secondary metabolites was named ‘azinothricin family’ after the identification of azinothricin as the first member in 1986 from Streptomyces sp. X-1950.

Figure 1.

Structures of polyoxypeptin A and B, and other natural products of Azinothricin family.

The compounds in this family exhibit diverse biological activities, such as potent antibacterial, antitumor [13,14], and anti-inflammatory activities [15], and acceleration of wound healing [16]. Both PLYA and PLYB were confirmed to be potent inducers of apoptosis. They can inhibit the proliferation of apoptosis-resistant AsPC-1 cells with IC50 values of 0.062 and 0.015 μg/mL. They can also induce early cell death in human pancreatic adenocarcinoma AsPC-1 cell lines with ED50 values of 0.08 and 0.17 μg/mL, more efficiently than adriamycin and vinblastine that can’t induce death of AsPC-1 cells even at 30 μg/mL [2]. In addition, they are able to induce apoptotic morphology and internucleosomal DNA fragmentation in AsPC-1 cell lines at low concentrations [17].

Polyoxypeptins (A and B) possess a variety of attractive biosynthetic features in their structures. The C15 acyl side chain may present a unique extension unit in polyketide synthase (PKS) assembly line probably derived from isoleucine [18]. The cyclo-depsipeptide core consists of six unusual amino acid residues at high oxidation states, including 3-hydroxyleucine, piperazic acid, N-hydroxyalanine, 5-hydroxypiperazic acid (for PLYA) or piperazic acid (for PLYB), 3-hydroxy - 3-methylproline, and N-hydroxyvaline. The most intriguing is the hydroxylation at α-amino groups of the l-alanine and l-valine, different from that at terminal amino group of ornithine or lysine in siderophore biosynthesis [19]. It is worth to note that (2S, 3R) -3-hydroxy - 3-methylproline presents a synthetic challenge [20]. Both structural novelty and biological activity of polyoxypeptins have spurred much interest in understanding the biosynthetic mechanism and employing biosynthesis and combinatorial biosynthesis to create new polyoxypeptin derives.

Here, we report the identification and characterization of the biosynthetic gene cluster for PLYA based on the genome sequencing, bioinformatics analysis, and systematic gene disruptions. The five stand-alone nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) domains were confirmed to be essential for PLYA biosynthesis, putatively involved in the biosynthesis of the unusual building blocks for assembly of the peptide backbone. Furthermore, three hydroxylases and two P450 enzymes were genetically characterized to be involved in the biosynthesis of PLYA. Among them, the P450 enzyme PlyM may play a role in transforming PLYB to PLYA.

Results and discussion

Identification and analysis of the ply gene cluster

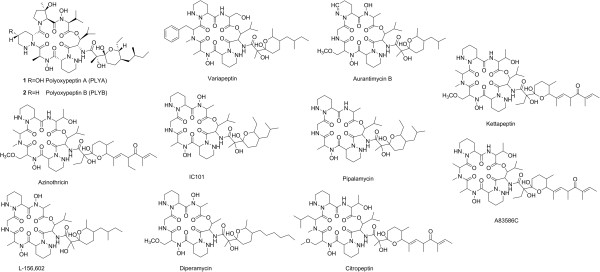

Whole genome sequencing of Streptomyces sp. MK498-98 F14 using the 454 sequencing technology yielded 11,068,848 bp DNA sequence spanning 528 contigs. Based on the structural analysis of PLYs, we hypothesized that PLYs are assembled by a hybrid PKS/NRPS system. Bioinformatics analysis of the whole genome revealed at least 20 NRPS genes and 70 PKS genes. Among them, the contig00355 (48439 bp DNA sequence) attracted our attention because it contains 7 putative NRPS genes and 4 PKS genes encoding total 4 PKS modules that perfectly match the assembly of the C15 acyl side chain based on the colinearity hypothesis [21]. Moreover, orf14777 (plyP) annotated as an l-proline-3-hydroxylase may be involved in the hydroxylation of 3-methylproline, one of the proposed precursor of PLYA [18]. NRPS analysis program revealed that 7 NRPS genes encode a free-standing peptidyl carrier protein (PCP) (PlyQ), 3 stand-alone thioesterase (TE) domains (PlyI, PlyS, and PlyY), and 3 NRPS modules that are not sufficient for assembly of the hexapeptide. Therefore, we continued to find another relevant contig00067 (83207 bp DNA sequence) contains 4 NRPS genes encoding a free-standing adenylation (A) domain (PlyC) and PCP (PlyD), and 3 NRPS modules. Taken together, the total 6 NRPS modules and 4 PKS modules are sufficient for the assembly of PLYs.

To confirm involvement of the genes in these two contigs by disruption of specific NRPS genes, a genomic library of Streptomyces sp. MK498-98 F14 was constructed using SuperCos1 [22] and ~3000 clones were obtained. Two pairs of primers (Additional file 1: Table S3) were designed on the base of two hydroxylases (PlyE and PlyP) from the contig00067 and contig00355, respectively, and used to screen the cosmid library using PCR method [23]. 10 positive cosmids derived from the primer of plyE and 11 positive cosmids derived from the primer of plyP were obtained. Interestingly, these two sets of cosmids overlapped one same cosmid, 15B10, which gave the further evidence that these two contigs belong to the same contig (Figure 2A). Thus, we used 15B10 as a template to fill the gap between these two contigs by PCR sequencing and got a 131,646 bp contiguous DNA sequence (Figure 2A). Subsequently, a NRPS gene orf14800 (plyH) was inactivated by replacement of plyH with apramycin resistant gene (aac(3)IV-oriT) cassette in the genome of Streptomyces sp. MK498-98 F14 (Additional file 1: Scheme S1). The resulting double-crossover mutant completely abolished the production of PLYA (Figure 3, trace i), confirming that the genes in this region are responsible for biosynthesis of PLYs.

Figure 2.

The biosynthetic gene cluter and proposed biosynthetic pathways for PLYA. A, Organization of the genes for the biosynthesis of PLYA. Their putative functions were indicated by color-labeling. B, the proposed model for PLYA skeleton assembly driven by the hybrid PKS/NRPS system. KS: Ketosynthase; AT: Acyltransferase; ACP: Acyl carrier protein; DH: Dehydratase; KR: Ketoreductase; ER: Enoyl reductase; A: Adenylation domain; PCP: Peptidyl carrier protein; C: Condensation domain; E: Epimerase domain; M: Methyltransferase; TE: Thioesterase. C, the proposed pathway for the biosynthesis of 3 (2-(2-methylbutyl)malonyl-ACP). D, the biosynthesis of 4 (l-piperazic acid). E, the proposed pathway for the biosynthesis of the building blocks 5 (N-hydroxylvaline) and 6 (N-hydroxylalanine). F and G, the proposed biosynthetic pathways of the building blocks 7 ((R)-3-hydroxy-3-methyproline) and 8 (3-hydroxyleucine).

Figure 3.

Verification of the ply gene cluster. LC-MS analysis (extracted ion chromatograms of m/z [M + H]+ 969.5 corresponding to PLYA) of Streptomyces sp. MK498-98 F14 wild type (indicated with WT) and mutants (Δorf1, Δorf11, and ΔplyH).

Bioinformatics analysis suggested that 37 open reading frames (ORFs, Figure 2A and Table 1) spanning 75 kb in this region were proposed to constitute the ply gene cluster based on the functional assignment of the deduced gene products. Among them, 4 modular type I PKS genes (plyTUVW) and 4 modular NRPS genes (plyXFGH) encoding 4 PKS modules and 6 NRPS modules are present for the assembly of the PLY core structure (Figure 2B). Other 6 NRPS genes (plyCDQISY) encode an A domain, two PCPs, and three TEs that are free-standing from the modular NRPSs. They are suggested to be involved in the biosynthesis of nonproteinogenic amino acid building blocks. 6 genes (orf5-orf10) are proposed to be involved in the biosynthesis of a novel extender unit for PKS assembly (Figure 2C). There are 6 genes (orf4 and plyEMOPR) encoding putative hydroxylases or oxygenases that are proposed to responsible for the biosynthesis of unusual building blocks or post-modifications (Figure 2D-G). There are 2 ABC transporter genes (plyJ and plyK) and 4 putative regulatory genes (orf2, plyB, plyL, and plyZ). In addition, an aminotransferase gene (plyN) is located in the center of the ply gene cluster that is probably involved in the biosynthesis of the novel PKS extender unit (3) (Figure 2C).

Table 1.

Deduced functions of ORFs in the biosynthetic gene cluster of PLYA

| Gene | Sizea | Accession no. | Proposed function | Homologous protein species | Identity/Similarity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

orf03399 |

384 |

YP_003099796 |

Nucleotidyl transferase |

Actinosynnema mirum DSM 43827 |

64/73 |

|

orf03396 |

309 |

YP_004903951 |

putative sugar kinase |

Kitasatospora setae KM-6054 |

50/62 |

|

orf1 |

422 |

YP_003099794 |

3-dehydroquinate synthase |

Actinosynnema mirum DSM 43827 |

56/69 |

|

orf2 |

128 |

EID72461 |

MarR family transcriptional regulator |

Rhodococcus imtechensis RKJ300 |

71/83 |

|

orf3 |

146 |

ZP_09957194 |

Hypothetical protein |

Streptomyces chartreusis NRRL 12338 |

75/84 |

|

orf4 |

566 |

CAJ61212 |

Putative polyketide oxygenase/hydroxylase |

Frankia alni ACN14a |

77/83 |

|

orf5 |

377 |

ZP_04706918 |

Alcohol dehydrogenase BadC |

Streptomyces roseosporus NRRL 11379 |

76/86 |

|

orf6 |

312 |

ZP_06582592 |

3-oxoacyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] synthase III |

Streptomyces roseosporus NRRL 15998 |

71/82 |

|

orf7 |

82 |

ZP_04706920 |

Hypothetical protein |

Streptomyces roseosporus NRRL 11379 |

59/75 |

|

orf8 |

82 |

ZP_04706921 |

Dihydrolipoamide succinyltransferase |

Streptomyces roseosporus NRRL 11379 |

65/81 |

|

orf9 |

326 |

ZP_06582595 |

2-oxoisovalerate dehydrogenase |

Streptomyces roseosporus NRRL 15998 |

75/87 |

|

orf10 |

303 |

ZP_04706923 |

Pyruvate dehydrogenase |

Streptomyces roseosporus NRRL 11379 |

74/84 |

|

plyA |

71 |

YP_640626 |

MbtH-like protein |

Mycobacterium sp. MCS |

80/87 |

|

plyB |

225 |

YP_712760 |

Putative regulator |

Frankia alni ACN14a |

76/84 |

|

plyC |

528 |

YP_712761 |

A |

Frankia alni ACN14a |

77/85 |

|

plyD |

77 |

YP_712762 |

PCP |

Frankia alni ACN14a |

85/94 |

|

plyE |

395 |

YP_712763 |

Putative hydroxylase |

Frankia alni ACN14a |

76/86 |

|

plyF |

2583 |

ABV56588 |

C-A-PCP-E-C-A-PCP |

Kutzneria sp. 744 |

56/68 |

|

plyG |

2809 |

ZP_05519638 |

C-A-PCP-E-C-A-PCP |

Streptomyces hygroscopicus ATCC 53653 |

73/82 |

|

plyH |

1662 |

BAH04161 |

C-A-M-PCP-TE |

Streptomyces triostinicus |

72/82 |

|

plyI |

247 |

YP_712767 |

TE |

Frankia alni ACN14a |

80/87 |

|

plyJ |

312 |

YP_003112824 |

Daunorubicin resistance ABC transporter |

Catenulispora acidiphila DSM 44928 |

78/90 |

|

plyK |

253 |

YP_712769 |

ABC transporter system |

Frankia alni ACN14a |

71/81 |

|

plyL |

1043 |

YP_003112826 |

Transcriptional regulator |

Catenulispora acidiphila DSM 44928 |

72/80 |

|

plyM |

412 |

AAT45271 |

Cytochrome P450 monooxygenase |

Streptomyces tubercidicus |

43/59 |

|

plyN |

450 |

ZP_04604097 |

Aminotransferase class I and II |

Micromonospora sp. ATCC 39149 |

58/70 |

|

plyO |

308 |

ZP_03862696 |

Polyketide fumonisin |

Kribbella flavida DSM 17836 |

48/64 |

|

plyP |

270 |

ZP_04292518 |

L-proline 3-hydroxylase type II |

Bacillus cereus R309803 |

32/51 |

|

plyQ |

88 |

YP_712776 |

PCP |

Frankia alni ACN14a |

76/89 |

|

plyR |

415 |

YP_712777 |

Cytochrome P450 monooxygenase |

Frankia alni ACN14a |

77/85 |

|

plyS |

245 |

AAT45287 |

TE |

Streptomyces tubercidicus |

70/81 |

|

plyT |

1031 |

YP_712779 |

KS-AT-ACP |

Frankia alni ACN14a |

71/80 |

|

plyU |

1872 |

YP_712780 |

KS-AT-DH-KR-ACP |

Frankia alni ACN14a |

69/79 |

|

plyV |

2199 |

YP_712781 |

KS-AT-DH-ER-KR-ACP |

Frankia alni ACN14a |

70/78 |

|

plyW |

1041 |

YP_712782 |

KS-AT-ACP |

Frankia alni ACN14a |

72/82 |

|

plyX |

1080 |

YP_712783 |

C-A-PCP |

Frankia alni ACN14a |

62/72 |

|

plyY |

253 |

ZP_04472110 |

TE |

Streptosporangium roseum DSM 43021 |

70/78 |

|

plyZ |

79 |

YP_001612061 |

LysR family transcriptional regulator |

Sorangium cellulosum |

65/77 |

|

orf11 |

287 |

YP_702564 |

Hypothetical protein |

Rhodococcus jostii RHA1 |

56/73 |

| orf14742 | 170 | YP_002777514 | Hypothetical protein ROP_03220 | Rhodococcus opacus B4 | 51/63 |

aNumbers are in amino acids.

Upstream of the ply gene cluster, three genes, orf03394 (orf1), orf03396 and orf03399, encoding proteins with similarities to 3-dehydroquinate synthase, sugar kinase and nucleotidyl transferase respectively, seemingly have no relationship with the biosynthesis of PLYA. orf03392 (orf2), adjacent to orf1, is predicted to encode a protein with similarity to a transcriptional regulator, which may be involved in the biosynthesis of PLYs. Downstream of the ply gene cluster, three genes, orf14746 (plyZ), orf14744 (orf11) and orf14742 encode proteins with similarities to LysR family transcriptional regulator, hypothetical protein ROP_29250 and hypothetical protein ROP_03220. To prove that the genes beyond this cluster are not related to PLY biosynthesis, we inactivated orf1 and orf11. The resulting mutants have no effect on the PLYA production (Figure 3, trace ii and iii), indicating that the 37 ORFs-contained ply gene cluster is responsible for the PLYs biosynthesis.

Assembly of the C15 acyl side chain by PKSs

Within the ply cluster, 4 modular type I PKS genes (plyTUVW) encode four PKS modules, the organization of which is accordant with the assembly of the C15 acyl side chain of PLYA via three steps of elongation from the propionate starter unit (Figure 2B). Both PlyT and PlyW consist of ketosynthase (KS), acyltransferase (AT), and acyl carrier protein (ACP). However, the active site Cys (for transthioesterification) of the PlyT-KS is replaced with Gln (Additional file 1: Figure S1), so it belongs to the so called “KSQ” that often occurs in the loading module of PKS system [24]. Therefore, PlyT acts as a loading module for formation of the propionate starter unit by catalyzing decarboxylation of methylmalonyl group after tethering onto ACP (Figure 2B). The conserved regions of AT domain including the active site motif GHSQG [25] in both PlyT and PlyW (Additional file 1: Figure S2), along with substrate specificity code (YASH) [26] indicate that both ATs are specific for methylmalonyl-CoA, consistent with the structure of the side chain of PLYA (Figure 2B). In PlyU, in addition to KS, AT, and ACP domains, a dehydratase (DH) domain and a ketoreductase (KR) domain are present. However, the DH domain here is believed to be nonfunctional because the key amino acid residue H of the conserved motif HxxxGxxxxP [27] is replaced by Gln (Additional file 1: Figure S3). The conserved motif of PlyU-AT for substrate selectivity is VPGH, neither including the serine residue in YASH for methylmalonyl-CoA nor phenylalanine residue in HAFH for malonyl-CoA (Additional file 1: Figure S2). These changes may broaden the substrate binding pocket and enhance hydrophobicity of the substrate binding pocket, supporting that PlyU is able to recognize 2-(2-methylbutyl)malonyl 3 as an unusual extender unit (Figure 2C). Compared to PlyU, PlyV contains an active DH domain and an enoyl reductase (ER) domain. The conserved motif (HAFH) of PlyV-AT signifies it specific for malonyl-CoA as the extender unit (Figure 2B and Additional file 1: Figure S2). Taken together, PlyTUVW seem to be sufficient for the assembly of the C15 acyl side chain of PLYA.

Biosynthesis of 2-(2-methylbutyl)malonyl extender unit 3

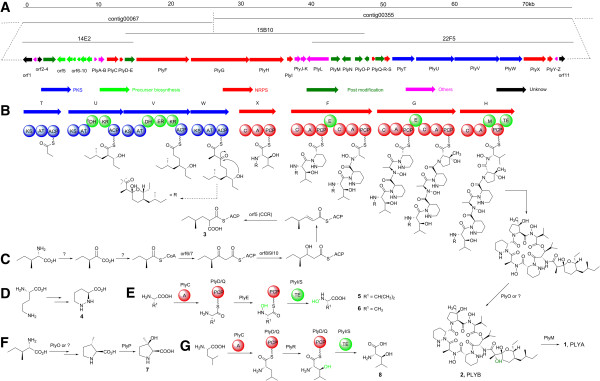

The structural analysis of PLYs and PKS architecture suggest that an unusual PKS extender unit 2-(2-methylbutyl)malonyl-CoA (or ACP, 3) is required for the assembly of the C15 acyl side chain of PLYs. The biosynthesis of the 2-(2-methylbutyl)malonyl-CoA (or ACP) extender unit 3 would involve a reductive carboxylation mediated by a crotonyl-CoA reductase/carboxylase (CCR) homolog. Similar reactions have been reported for formation of ethylmalony-CoA [28,29], 2-(2-chloroethyl)malonyl-CoA [30], and hexylmalonyl-CoA [31], as well as proposed for involvement of biosynthesis of cinnabaramides [32], thuggacins [33], sanglifehrins [34], germicidins and divergolides [35], ansalactams [36] and many other natural products. Analysis of the ply cluster reveals orf5 encoding a CCR TgaD homolog (identity/similarity, 46%/59%) that was proposed to be involved in the biosynthesis of hexylmalonyl-CoA, an extender unit for the assembly of thuggacin [33]. orf6, adjacent to orf5, encodes a protein shared 71% identity and 81% similarity with 3-oxoacyl-ACP synthase III from S. roseosporus NRRL 15998. The gene orf7, located upstream of orf6, encodes an ACP that contains a catalytic motif DLDLDSL (the Serine is for phosphopantethein modification) [24]. The presence of these two genes indicates that the extender unit 2-(2-methylbutyl)malonyl may be tethered to ACP, not to CoA. In study of the biosynthesis of isobutylmalonyl-CoA extender unit for germicidins and divergolides, CCR, KSIII and HBDH (a 3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA hydrogenase) are transcribed in the same operon [35]. orf567 and other three genes orf8910 also constitute an operon (Figure 2A). The genes orf8910 encode α-keto acid dehydrogenase E2 component, E1 component β and α subunits, respectively, suggesting their involvement of the biosynthesis of 3 by reduction of the β-keto group (Figure 2C). Given that the previous feeding study with isotope-labeled precursor suggested this 2-(2-methylbutyl)malonyl unit derived from isoleucine via a transamination [18], we proposed that an aminotransferase is required for the formation of α-keto acid, as shown in Figure 2C. plyN is the only identified aminotransferase gene, so we constructed the ΔplyN mutant by replacement of the plyN gene with the aac(3)IV-oriT cassette (Additional file 1: Scheme S2). However, ΔplyN was found no effect on the PLYA production (Figure 4, trace viii), so we assume that other aminotransferases may mediate this transamination for the incorporation of C5 unit of isoleucine into 3 (Figure 2C).

Figure 4.

Characterization of the discrete NRPS domains and aminotransferase in vivo. LC-MS analysis (extracted ion chromatograms of m/z [M + H]+ 969.5 corresponding to PLYA) of Streptomyces sp. MK498-98F14 wild type (WT) and mutants (ΔplyC, ΔplyD, ΔplyQ, ΔplyI, ΔplyS, ΔplyY and ΔplyN).

Assembly of the cyclodepsipeptide by NRPSs

After the C15 acyl side chain is assembled by 4 modular PKSs, it is transferred to 3-hydroxyleucine via an amide bond formation catalyzed by a NRPS, thus initiating the assembly of the peptide core. Within the biosynthetic gene cluster, there are 4 genes plyFGHX encoding modular NRPS proteins. Both PlyF and PlyG consist of two modules with seven domains (C-A1-PCP-E-C-A2-PCP) (Figure 2B). Active epimerase (E) domains are present indicating that the amino acids activated by PlyF-A1 and PlyG-A1 should be converted into d-configuration. Among the six nonproteinogenic amino acid residues, only two piperazic acid residues are d-configuration, so these two A domains (PlyF-A1 and PlyG-A1) are proposed to recognize and activate l-piperazic acid (4, Figure 2D) that was confirmed to be derived from l-ornithine [37]. This assumption can be supported by the findings that PlyF-A1 shares 52-59% identity and 64-69% similarity to PlyG-A1, KtzH-A1 [38], and HmtL-A1 [39] (Additional file 1: Figure S4), and as well as the substrate specificity-conferring ten amino acids (DVFSVASYAK for PlyF-A1 and DVFSIAAYAK for PlyG-A1) are highly analogous to those of KtzH-A1 (DVFSVGPYAK) and HmtL-A1 (DVFSVAAYAK) [40,41]. Both KtzH-A1 and HmtL-A1 were proposed to recognize and activate l-piperazic acid [38,39]. PlyH contains five domains (C-A-M-PCP-TE) with a thioesterase (TE) domain present, indicating that PlyH is the last module of PLY NRPS system and responsible for the release and cyclization of the peptide chain via an ester bond formation. It is striking that an active methyltransferase (M) domain (containing the SAM-binding sites EXGXGXG) is present in the PlyH [42], but no N-methyl group is present in the structure of PLYs. The presence of this M domain remains enigmatic. Based on the PLY structure analysis and NRPS machinery [43], PlyH-A is proposed to recognize N-hydroxyvaline (5, Figure 2E) as its substrate, but not valine because its substrate specificity-conferring codon sequences (DAPFEALVEX) are significantly distinct from those found for valine-specificity (DALWMGGTFK) [44]. Subsequently, the whole sequence of PlyH-A shows 76% identity and 83% similarity to that of PlyF-A2, indicating that PlyF-A2 is specific for N-hydroxyalanine (6, Figure 2E and Additional file 1: Figure S5). These assignments are consistent with the amino acid sequence of the peptide core of PLYs. Finally, according to the collinearity of the NRPS modules and the building blocks of the NRPS-derived products, PlyG-A2 and PlyX would be proposed to recognize and activate (R)-3-hydroxy-3-methylproline (7, Figure 2F) and 3-hydroxyleucine (8, Figure 2G), respectively, although we can’t predict their substrates based on their substrate specificity codons (Additional file 1: Table S4). Taken together, six NRPS modules activate six non-natural amino acids, and the substrate recognized by each domain is exactly consistent with the structure of the cyclic depsipeptide of PLYs (Figure 2B).

Biosynthesis of nonproteinogenic amino acid building blocks

Except for the modular NRPSs, there are six discrete NRPS genes present in the ply gene cluster (Table 1 and Figure 2A), identified as an A domain (PlyC), two PCP domains (PlyD, PlyQ) and three TE domains (PlyI, PlyS, PlyY). To test whether these six free-standing domains were involved in the biosynthesis of PLYA, we constructed their disruption mutants by gene replacement with the aac(3)IV-oriT cassette (Additional file 1: Scheme S3-8). The mutant strains (ΔplyC, ΔplyD, ΔplyQ, ΔplyI and ΔplyS) completely abolished the production of PLYA (Figure 4, traces i-v), indicating that these 5 discrete NRPS domains are essential for the PLYA biosynthesis. However, the ΔplyY mutant strain still produced PLYA, but the productivity decreased in comparison with that of the wild type strain (Figure 4, trace vi and vii). Therefore, PlyY may act as a type II TE, probably playing an editing role in the biosynthesis of PLYA by hydrolyzing misincorporated building blocks. Multiple sequence alignment reveals that PlyY and typical type II TEs contain a conserved motif (GHSXG) and catalytic triad S/C-D-H that is consistent with hydrolytic function (Additional file 1: Figure S6) [45-47]. This catalytic triad is also present in PlyI and PlyS, indicating the hydrolytic function of PlyI and PlyS, as shown by Figure 2E and G.

The discrete NRPS domains have been found in many NRPS assembly lines responsible for the formation of nonproteinogenic building blocks [21,48]. For example, the conversion of proline to pyrrole-2-carboxylic acid, which is a precursor for the biosynthesis of pyoluteorin, prodigiosin, and clorobiocin [49], occurs while proline is activated by a discrete A domain and covalently tethered in a thioester linkage to a T domain. Since all the A domains of six modular NRPSs in the PLY biosynthetic pathway are proposed to recognize and activate nonproteinogenic amino acid building blocks, PlyCDQIS are assumed to be responsible for the formation of several monomers of PLYs from the natural amino acids. Given that we can’t predict the substrate based on the key residues of the substrate-binding pocket of PlyC (A domain), we propose that PlyC may activate multiple amino acids such as alanine and valine or leucine, and tether them to the corresponding PCPs (PlyD and PlyQ). After N-hydroxylation of alanine and valine (Figure 2E) as well as β-hydroxylation of leucine (Figure 2G), the matured building blocks are proposed to be released by discrete TEs (PlyI or PlyS, respectively) and activated again by PlyF-A2, PlyH, and PlyX, respectively (Figure 2B). Such processes are rare events in typical NRPS-driven biosynthetic pathways [21].

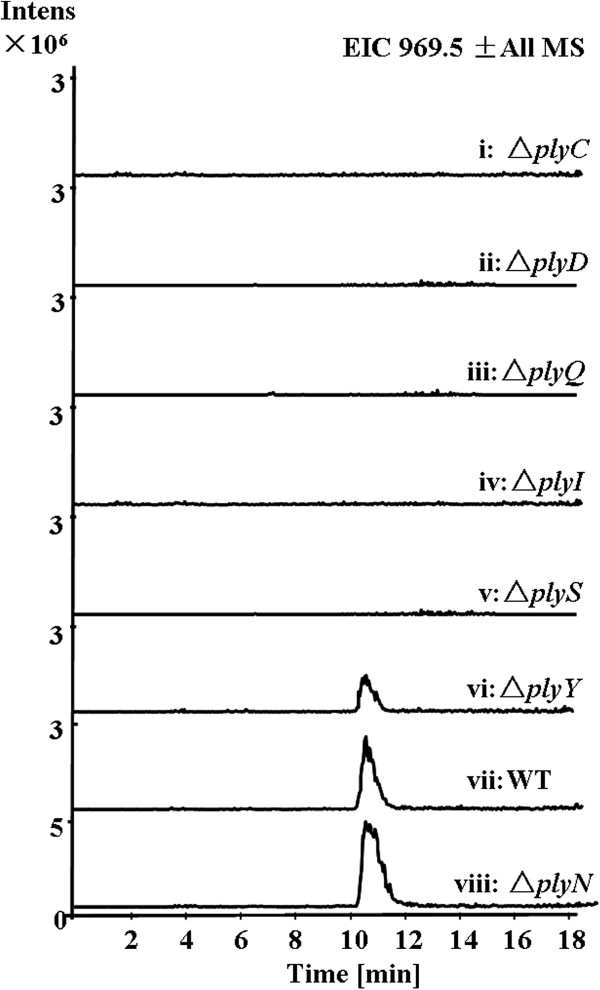

The depsipeptide core of PLYA is composed of 6 amino acids, 5 of which are hydroxylated. There are 6 genes encoding putative hydroxylases or oxygenases. For example, plyR encodes a cytochrome P450 monooxygenase that shows high homology (37% identity and 54% similarity) to NikQ that was demonstrated to catalyze β-hydroxylation of histidine tethered to PCP, so we could propose that PlyR may be involved in the formation of β-hydroxyleucine building block (Figure 2G). Indeed, inactivation of plyR resulted in loss of ability to produce PLYA (Figure 5A, trace i). Given that FAD-dependent monooxygenase CchB has been reported to catalyze the N-hydroxylation of the δ-amino group of ornithine in the biosynthetic pathway of the siderophore coelichelin [50], we proposed that PlyE, a FAD-dependent monooxygenase, may be responsible for N-hydroxylation of alanine and valine when they are activated and tethered to a PCP by A domain PlyC (Figure 2E). The ΔplyE mutant lost ability to produce PLYA (Figure 5A, trace ii), indicating its possible role in formation of N-hydroxyalanine and N-hydroxyvaline. PlyP, a l-proline 3-hydroxylase, should be responsible for hydroxylation of 3-methyl-l-proline that is biosynthesized from l-isoleucine demonstrated by isotope-feeding study (Figure 2F) [18]. Inactivation of plyP indeed abolished the production of PLYA (Figure 5A, trace iii). Recently, Tang and co-workers have reported that an α-ketoglutarate dependent dioxygenase EcdK catalyzes a sequential oxidations of leucine to form the immediate precursor of 4-methylproline [51]. In the ply cluster, the only gene plyO encodes an α-ketoglutarate dependent dioxygenase, but it doesn’t share any homology to EcdK. In contrast, PlyO shows 48% identity and 64% similarity to phytanoyl-CoA dioxygenase (YP_003381511 from Kribbella flavida DSM 17836). It remains unclear whether PlyO may be responsible for the hydroxylation of the carbon adjacent to the acyl group of the C15 acyl side chain or for the formation of 3-methyl-l-proline from l-isoleucine. orf4 encodes a FAD-binding oxygenase or hydroxylase with high homology to type II PKS-assembled aromatic compounds hydroxylase (Table 1). Its role in biosynthesis of PLYA remains unclear, but it might be involved in the biosynthesis of a building block because its inactivation abolished the PLY production (Figure 5A, trace iv).

Figure 5.

Characterization of the genes encoding hydroxylases or oxygenases. A, LC-MS analysis (extracted ion chromatograms of m/z [M + H]+ 969.5 corresponding to PLYA) of Streptomyces sp. MK498-98F14 wild type (WT) and mutants (ΔplyE, ΔplyP, ΔplyR, Δorf4, and ΔplyM). B, LC-MS analysis (extracted ion chromatograms of m/z [M + Na]+ 975.5 and 991.5 corresponding to PLYB and PLYA) of Streptomyces sp. MK498-98F14 wild type (WT) and the ΔplyM mutant. C, LC-MS analysis (extracted ion chromatograms of m/z [M + Na]+ 959.5 corresponding to the putative biosynthetic intermediate of PLYA lacking two hydroxyl groups) of Streptomyces sp. MK498-98F14 wild type (WT) and mutants (ΔplyE, ΔplyP, ΔplyR and ΔplyM). B was performed under the conditions: 35-95% B (linear gradient, 0–20 min), 100% B (21–25 min), 35% B (25-40 min) at the flow rate of 0.3 mL/min.

Piperazic acid is an attractive building block of many complex secondary metabolites such as Antrimycin [52], Chloptosin [53], Himastatin [39], Luzopeptin [54], Quinoxapeptin [55], Lydiamycin [56], Piperazimycin [57] and Sanglifehrin [58]. The detailed biosynthetic mechanisms by which piperazic acid are formed are not well understood. Recently, Walsh and coworkers demonstrated that KtzI, a homolog of lysine and ornithine N-hydroxylases catalyzes the conversion of ornithine into piperazic acid in kutzneride biosynthetic pathway [37]. No such a homolog was found in the ply gene cluster, but two putative homologs are located outside the ply gene cluster (Orf11257 and Orf14738), suggesting that the biosynthesis of piperazic acid may follow the same pathway (Figure 2D).

Genes putatively for post-modifications

Most modifications in PLYA biosynthesis take place for the formation of the non-natural building blocks. Recently, Ju and co-workers demonstrated that a cytochrome P450 monooxygenase HtmN catalyzes the hydroxylation of the piperazic acid after peptide formation [59]. There are two cytochrome P450 monooxygenase genes (plyM and plyR) in the ply cluster. PlyR was proposed to hydroxylate leucine that is tethered to a PCP, so we would assume that PlyM may catalyze the hydroxylation of piperazic acid unit as a post-modification although it doesn’t show any homology to HmtN [39]. To test this hypothesis, we constructed the double-crossover mutant by replacement of plyM with the aac(3)IV-oriT gene cassette that is not producing PLYA (Figure 5A, trace v), only accumulating PLYB (Figure 5B). These findings indicate that PlyM is responsible for the conversion of PLYB into PLYA (Figure 2B). To test whether other oxygenases or hydroxylases are involved in the post-modifications, the mass corresponding to the putative intermediate of PLYA lacking two hydroxyl groups was monitored for the mutant strains (Figure 5C). This mass is only detected from the fermentation broth of wide type and ΔplyM strains (Figure 5C, trace v and iv), not from other mutant strains (ΔplyE, ΔplyP and ΔplyR) indicating that the assembly of PLYA and possible intermediates is abolished. These data may support that these genes are involved in the formation of building blocks, not post-modifications. They also indicate that it is very likely to have two steps of post-hydroxylation modifications for maturation of PLYA (Figure 2B). When and how the hydroxylation at the α-carbon of the C15 acyl side chain takes place are still unclear.

Conclusions

We identified and characterized the ply gene cluster composed of 37 open reading frames (ORFs) by genomic sequencing and systematic gene disruptions. The biosynthetic pathway has been proposed based on bioinformatics analysis, the structural analysis of PLYs and genetic data. It was demonstrated that five discrete NRPS domains are essential for the biosynthesis of PLYs and proposed their roles in maturation of three unusual amino acid building blocks. The proposed biosynthetic pathway for PLYs will open the door to understand the biosynthesis of this family of secondary metabolites and set a stage to explore combinatorial biosynthesis to create new compounds with improved pharmaceutical properties.

Ethics statement

This study doesn’t involve human subjects or materials.

Methods

Strains, plasmids, primers and culture conditions

Strains, plasmids and primers used in the study are summarized in Additional file 1: Tables S1, S2 and S3 of the supplemental material. Escherichia coli strains were cultured on Luria-Bertani (LB) broth and agar medium at 37°C. Streptomyces sp. MK498-98 F14 and its mutant strains were cultivated at 30°C on the medium (yeast extract 0.4%, glucose 0.4%, malt extract 1%, agar 1.2%, pH 7.2) for sporulation and on 2CM [60] medium (soluble starch 1%, tryptone 0.2%, NaCl 0.1%, (NH4)2SO4 0.2%, K2HPO4 0.1%, MgSO4 0.1%, CaCO3 0.2%, agar 1.2% with 1 mL inorganic salt solution per liter, pH7.2) for conjugation. For fermentation, mycelia of strain MK498-98 F14 and its mutants from the solid plates were inoculated into a 500-mL Erlenmeyer flask containing 100 mL of a medium composed of glucose 1%, potato starch 1%, glycerol 1%, polypepton 0.5%, meat extract 0.5%, sodium chloride 0.5%, and calcium carbonate 0.32% (adjusted to pH 7.4) [2]. The culture was incubated at 28°C for six days on a rotatory shaker at 220 rpm.

General genetic manipulations and reagents

The general genetic manipulation in E. coli and Streptomyces were carried out following the standard protocols [22]. PCR amplifications were performed on a Veriti thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) using Taq DNA polymerase. DNA fragments and PCR products were purified from agarose gels using a DNA Gel Extraction Kit (Omega). Primers were synthesized in Sangong Biotech Co. Ltd. Company (Shanghai, China). All DNA sequencing was accomplished at Shanghai Majorbio Biotech Co. Ltd (Shanghai, China). Restriction enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA) and Fermentas (St. Leon-Rot, Germany). Taq DNA polymerase and DNA ligase were purchased from Takara Co. Ltd. Company (Dalian, China).

Genomic library construction and screening

A genomic cosmid library of Streptomyces sp. MK498-98 F14 derived from SuperCos1 was constructed according to the procedure as described by the SuperCos1 Cosmid Vector Kit. E. coli EPI300™-T1R, instead of E.coli XL1-Blue MR, was used as the host strain. The total number of recombinant clones was about 3000 and then stored at −70°C. Two pairs of primers for two hydroxylase genes, orf03374 (plyE) and orf14777 (plyP) were designed and used to screen the genomic cosmid library by PCR.

Genome sequencing and analysis

Genome sequencing was accomplished by 454 sequencing technology. Open reading frames were analyzed using the Frame Plot 3.0 beta online [61], and the analysis of the deduced function of the proteins were carried out by the NCBI website [62]. Primer design, multiple nucleotide sequence alignments and analysis were performed using the BioEdit. The NRPS-PKS architecture was analyzed by NRPS-PKS online website (http://nrps.igs.umaryland.edu/nrps/) [63] and the prediction of ten amino acid of the conserved substrate-binding pocket of the A domain was performed using the online program NRPS predictor (http://ab.inf.unituebingen.de/toolbox/index.php?view=domainpred) [64].

Construction of gene inactivation mutants

All the mutant strains in this study were generated by homologous recombination according to the standard method [65]. The target genes were replaced with an apramycin-resistance gene from pIJ773 on SuperCos1 by traditional PCR-targeting technique. Then the recombinant plasmids were transformed into E. coli S17-1 cells for conjugation. The exconjugants would appear three days later and could be transferred to a new growth medium supplemented with apramycin (60 μg/mL) and nalidixic acid (100 μg/mL). Double-crossover mutants were identified through diagnostic PCR with corresponding primers (Additional file 1: Table S3).

LC-MS analyses of wild type and mutant strains

After finishing the fermentation, the culture broth of wild type and mutant strains were extracted by equal volume of ethyl acetate. The supernatant of the ethyl acetate phase was concentrated by rotary evaporator under the reduced pressure and finally dissolved in methanol (400 μL) for the LC-MS analysis using the Agilent 1100 series LC/MSD Trap system. The conditions for the LC-MS analysis are as follows: 55-100% B (linear gradient, 0–25 min, solvent A is water containing 0.1% formic acid, solvent B is acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid), 100% B (26–30 min) at the flow rate of 0.3 mL/min with a reverse-phase column ZORBAX SB-C18 (Agilent, 5 μm, 150 mm × 4.6 mm). Figure 4B was recorded with the conditions: 35-95% B (linear gradient, 0–20 min), 100% B (21–25 min), 35%B (25–40 min) at the flow rate of 0.3 mL/min.

Nucleotide sequence accession number

The sequence of the polyoxypeptin A biosynthetic gene cluster was deposited in GenBank with accession number KF386858.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SL designed this study; YD, YW, TH performed the experiments; YD, MT, ZD and SL analyzed data; YD and SL wrote this manuscript; MT and ZD edited this manuscript; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Electronic supplementary materials are available: bacterial strains (Table S1), plasmids (Table S2), primers (Table S3), and the substrate-specific codon sequences (Table S4); sequence alignment (Figures S1-6) and mutant construction (Schemes S1-8).

Contributor Information

Yanhua Du, Email: duyanhuafly@sjtu.edu.cn.

Yemin Wang, Email: wangyemin@sjtu.edu.cn.

Tingting Huang, Email: THuang@scripps.edu.

Meifeng Tao, Email: tao_meifeng@sjtu.edu.cn.

Zixin Deng, Email: zxdeng@sjtu.edu.cn.

Shuangjun Lin, Email: linsj@sjtu.edu.cn.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the 973 programs (2010CB833805 for SL) and (2009CB118901 for ZD) from MOST, the key project (311018) from MOE and NSFC (31070057 for SL; 31121064 for ZD).

References

- Umezawa KNK, Uemura T. et al. Polyoxypeptin isolated from Streptomyces: a bioactive cyclic depsipeptide containing the novel amino acid 3-hydroxy-3-methylproline. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39(11):1389–1392. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(98)00031-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Umezawa K, Nakazawa K, Ikeda Y, Naganawa H, Kondo S. Polyoxypeptins A and B produced by Streptomyces: apoptosis-inducing cyclic depsipeptides containing the novel amino acid (2S,3R)-3-hydroxy-3-methylproline. J Org Chem. 1999;64(9):3034–3038. doi: 10.1021/jo981512n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smitka TA, Deeter JB, Hunt AH, Mertz FP, Ellis RM, Boeck LD, Yao RC. A83586C, a new depsipeptide antibiotic. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1988;41(6):726–733. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.41.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grafe U, Schlegel R, Ritzau M, Ihn W, Dornberger K, Stengel C, Fleck WF, Gutsche W, Hartl A, Paulus EF. Aurantimycins, new depsipeptide antibiotics from Streptomyces aurantiacus IMET 43917. Production, isolation, structure elucidation, and biological activity. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1995;48(2):119–125. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.48.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maehr H, Liu CM, Palleroni NJ, Smallheer J, Todaro L, Williams TH, Blount JF. Microbial products. VIII. Azinothricin, a novel hexadepsipeptide antibiotic. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1986;39(1):17–25. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.39.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa Y, Nakagawa M, Toda Y, Seto H. A new depsipeptide antibiotic, citropeptin. Agric Biol Chem. 1990;54(4):1007–1011. doi: 10.1271/bbb1961.54.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto N, Momose I, Umekita M, Kinoshita N, Chino M, Iinuma H, Sawa T, Hamada M, Takeuchi T. Diperamycin, a new antimicrobial antibiotic produced by Streptomyces griseoaurantiacus MK393-AF2. I. Taxonomy, fermentation, isolation, physico-chemical properties and biological activities. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1998;51(12):1087–1092. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.51.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maskey RP, Fotso S, Sevvana M, Uson I, Grun-Wollny I, Laatsch H. Kettapeptin: isolation, structure elucidation and activity of a new hexadepsipeptide antibiotic from a terrestrial Streptomyces sp. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2006;59(5):309–314. doi: 10.1038/ja.2006.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umezawa K, Ikeda Y, Naganawa H, Kondo S. Biosynthesis of the lipophilic side chain in the cyclic hexadepsipeptide antibiotic IC101. J Nat Prod. 2002;65(12):1953–1955. doi: 10.1021/np0202069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensens OD, Borris RP, Koupal LR, Caldwell CG, Currie SA, Haidri AA, Homnick CF, Honeycutt SS, Lindenmayer SM, Schwartz CD. et al. L-156,602, a C5a antagonist with a novel cyclic hexadepsipeptide structure from Streptomyces sp. MA6348. Fermentation, isolation and structure determination. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1991;44(2):249–254. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.44.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchihata Y, Ando N, Ikeda Y, Kondo S, Hamada M, Umezawa K. Isolation of a novel cyclic hexadepsipeptide pipalamycin from Streptomyces as an apoptosis-inducing agent. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2002;55(1):1–5. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.55.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa M, Hayakawa Y, Adachi K, Seto H. A new depsipeptide antibiotic, variapeptin. Agric Biol Chem. 1990;54(3):791–794. doi: 10.1271/bbb1961.54.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai Y, Yoshida T, Tsujita T, Ochiai K, Agatsuma T, Saitoh Y, Tanaka F, Akiyama T, Akinaga S, Mizukami T. GE3, a novel hexadepsipeptide antitumor antibiotic, produced by Streptomyces sp. I. Taxonomy, production, isolation, physico-chemical properties, and biological activities. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1997;50(8):659–664. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.50.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agatsuma T, Sakai Y, Mizukami T, Saitoh Y. GE3, a novel hexadepsipeptide antitumor antibiotic produced by Streptomyces sp. II. Structure determination. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1997;50(8):704–708. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.50.704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji RF, Yamakoshi J, Uramoto M, Koshino H, Saito M, Kikuchi M, Masuda T. Anti-inflammatory effects and specificity of L-156,602: comparison of effects on concanavalin A and zymosan-induced footpad edema, and contact sensitivity response. Immunopharmacology. 1995;29(1):79–87. doi: 10.1016/0162-3109(95)00047-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oelke AJ, France DJ, Hofmann T, Wuitschik G, Ley SV. Piperazic acid-containing natural products: isolation, biological relevance and total synthesis. Nat Prod Rep. 2011;28(8):1445–1471. doi: 10.1039/c1np00041a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umezawa K, Nakazawa K, Uchihata Y, Otsuka M. Screening for inducers of apoptosis in apoptosis-resistant human carcinoma cells. Adv Enzyme Regul. 1999;39:145–156. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2571(98)00022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umezawa K, Ikeda Y, Kawase O, Naganawa H, Kondo S. Biosynthesis of polyoxypeptin A: novel amino acid 3-hydroxy-3-methylproline derived from isoleucine. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 1. pp. 1550–1553.

- Kodani S, Bicz J, Song L, Deeth RJ, Ohnishi Kameyama M, Yoshida M, Ochi K, Challis GL. Structure and biosynthesis of scabichelin, a novel tris-hydroxamate siderophore produced by the plant pathogen Streptomyces scabies 87.22. Org Biomol Chem. 2013;11(28):4686–4694. doi: 10.1039/c3ob40536b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen JW, Qin DG, Zhang HW, Yao ZJ. Studies on the synthesis of (2S,3R)-3-hydroxy-3-methylproline via C2-N bond formation. J Org Chem. 2003;68(19):7479–7484. doi: 10.1021/jo0349328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischbach MA, Walsh CT. Assembly-line enzymology for polyketide and nonribosomal Peptide antibiotics: logic, machinery, and mechanisms. Chem Rev. 2006;106(8):3468–3496. doi: 10.1021/cr0503097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieser TBM, Chater KF, Butter MJ, Hopwood D. Practical Streptomyces genetics:a laboratory manual. Norwich, UK, Norwich: John Innes Foundation; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Sun Y, Liu T, Zhou X, Bai L, Deng Z. Cloning of separate meilingmycin biosynthesis gene clusters by use of acyltransferase-ketoreductase didomain PCR amplification. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76(10):3283–3292. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02262-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keatinge-Clay AT. The structures of type I polyketide synthases. Nat Prod Rep. 2012;29(10):1050–1073. doi: 10.1039/c2np20019h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav G, Gokhale RS, Mohanty D. Computational approach for prediction of domain organization and substrate specificity of modular polyketide synthases. J Mol Biol. 2003;328(2):335–363. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00232-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S, Tsai SC. The type I fatty acid and polyketide synthases: a tale of two megasynthases. Nat Prod Rep. 2007;24(5):1041–1072. doi: 10.1039/b603600g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai SC, Ames BD. Structural enzymology of polyketide synthases. Methods Enzymol. 2009;459:17–47. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)04602-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erb TJ, Berg IA, Brecht V, Muller M, Fuchs G, Alber BE. Synthesis of C5-dicarboxylic acids from C2-units involving crotonyl-CoA carboxylase/reductase: the ethylmalonyl-CoA pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(25):10631–10636. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702791104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erb TJ, Brecht V, Fuchs G, Muller M, Alber BE. Carboxylation mechanism and stereochemistry of crotonyl-CoA carboxylase/reductase, a carboxylating enoyl-thioester reductase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(22):8871–8876. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903939106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eustaquio AS, McGlinchey RP, Liu Y, Hazzard C, Beer LL, Florova G, Alhamadsheh MM, Lechner A, Kale AJ, Kobayashi Y. et al. Biosynthesis of the salinosporamide A polyketide synthase substrate chloroethylmalonyl-coenzyme A from S-adenosyl-L-methionine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(30):12295–12300. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901237106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quade N, Huo L, Rachid S, Heinz DW, Muller R. Unusual carbon fixation gives rise to diverse polyketide extender units. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8(1):117–124. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachid S, Huo L, Herrmann J, Stadler M, Kopcke B, Bitzer J, Muller R. Mining the cinnabaramide biosynthetic pathway to generate novel proteasome inhibitors. Chembiochem. 2011;12(6):922–931. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201100024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buntin K, Irschik H, Weissman KJ, Luxenburger E, Blocker H, Muller R. Biosynthesis of thuggacins in myxobacteria: comparative cluster analysis reveals basis for natural product structural diversity. Chem Biol. 2010;17(4):342–356. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu X, Jiang N, Xu F, Shao L, Tang G, Wilkinson B, Liu W. Cloning, sequencing and characterization of the biosynthetic gene cluster of sanglifehrin A, a potent cyclophilin inhibitor. Mol Biosyst. 2011;7(3):852–861. doi: 10.1039/c0mb00234h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, Ding L, Hertweck C. A branched extender unit shared between two orthogonal polyketide pathways in an endophyte. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2011;50(20):4667–4670. doi: 10.1002/anie.201008265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson MC, Nam SJ, Gulder TA, Kauffman CA, Jensen PR, Fenical W, Moore BS. Structure and biosynthesis of the marine streptomycete ansamycin ansalactam A and its distinctive branched chain polyketide extender unit. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133(6):1971–1977. doi: 10.1021/ja109226s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann CS, Jiang W, Heemstra JR Jr, Gontang EA, Kolter R, Walsh CT. Biosynthesis of piperazic acid via N5-hydroxy-ornithine in Kutzneria spp. 744. Chembiochem. 2012;13(7):972–976. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201200054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimori DG, Hrvatin S, Neumann CS, Strieker M, Marahiel MA, Walsh CT. Cloning and characterization of the biosynthetic gene cluster for kutznerides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(42):16498–16503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708242104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Wang Z, Huang H, Luo M, Zuo D, Wang B, Sun A, Cheng YQ, Zhang C, Ju J. Biosynthesis of himastatin: assembly line and characterization of three cytochrome P450 enzymes involved in the post-tailoring oxidative steps. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2011;50(34):7797–7802. doi: 10.1002/anie.201102305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stachelhaus T, Mootz HD, Marahiel MA. The specificity-conferring code of adenylation domains in nonribosomal peptide synthetases. Chem Biol. 1999;6(8):493–505. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(99)80082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challis GL, Ravel J, Townsend CA. Predictive, structure-based model of amino acid recognition by nonribosomal peptide synthetase adenylation domains. Chem Biol. 2000;7(3):211–224. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(00)00091-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JL, McMillan FM. SAM (dependent) I AM: the S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferase fold. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2002;12(6):783–793. doi: 10.1016/S0959-440X(02)00391-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Dohren H, Keller U, Vater J, Zocher R. Multifunctional Peptide Synthetases. Chem Rev. 1997;97(7):2675–2706. doi: 10.1021/cr9600262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Rokni-Zadeh H, De Vleeschouwer M, Ghequire MG, Sinnaeve D, Xie GL, Rozenski J, Madder A, Martins JC, De Mot R. The antimicrobial compound xantholysin defines a new group of Pseudomonas cyclic lipopeptides. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e62946. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claxton HB, Akey DL, Silver MK, Admiraal SJ, Smith JL. Structure and functional analysis of RifR, the type II thioesterase from the rifamycin biosynthetic pathway. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(8):5021–5029. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808604200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koglin A, Lohr F, Bernhard F, Rogov VV, Frueh DP, Strieter ER, Mofid MR, Guntert P, Wagner G, Walsh CT. et al. Structural basis for the selectivity of the external thioesterase of the surfactin synthetase. Nature. 2008;454(7206):907–911. doi: 10.1038/nature07161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer D, Mootz HD, Linne U, Marahiel MA. Regeneration of misprimed nonribosomal peptide synthetases by type II thioesterases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(22):14083–14088. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212382199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S, Huang T, Shen B. Tailoring enzymes acting on carrier protein-tethered substrates in natural product biosynthesis. Methods Enzymol. 2012;516:321–343. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394291-3.00008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas MG, Burkart MD, Walsh CT. Conversion of L-proline to pyrrolyl-2-carboxyl-S-PCP during undecylprodigiosin and pyoluteorin biosynthesis. Chem Biol. 2002;9(2):171–184. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(02)00100-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohlmann V, Marahiel MA. Delta-amino group hydroxylation of L-ornithine during coelichelin biosynthesis. Org Biomol Chem. 2008;6(10):1843–1848. doi: 10.1039/b801016a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W, Cacho RA, Chiou G, Garg NK, Tang Y, Walsh CT. EcdGHK are three tailoring iron oxygenases for amino acid building blocks of the echinocandin scaffold. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135(11):4457–4466. doi: 10.1021/ja312572v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada N, Morimoto K, Naganawa H, Takita T, Hamada M, Maeda K, Takeuchi T, Umezawa H. Antrimycin, a new peptide antibiotic. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1981;34(12):1613–1614. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.34.1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umezawa K, Ikeda Y, Uchihata Y, Naganawa H, Kondo S. Chloptosin, an apoptosis-inducing dimeric cyclohexapeptide produced by Streptomyces. J Org Chem. 2000;65(2):459–463. doi: 10.1021/jo991314b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox KR, Davies H, Adams GR, Portugal J, Waring MJ. Sequence-specific binding of luzopeptin to DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16(6):2489–2507. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.6.2489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingham RB, Hsu AH, O'Brien JA, Sigmund JM, Sanchez M, Gagliardi MM, Heimbuch BK, Genilloud O, Martin I, Diez MT. et al. Quinoxapeptins: novel chromodepsipeptide inhibitors of HIV-1 and HIV-2 reverse transcriptase. I. The producing organism and biological activity. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1996;49(3):253–259. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.49.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Roemer E, Sattler I, Moellmann U, Christner A, Grabley S. Lydiamycins A-D: cyclodepsipetides with antimycobacterial properties. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2006;45(19):3067–3072. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller ED, Kauffman CA, Jensen PR, Fenical W. Piperazimycins: cytotoxic hexadepsipeptides from a marine-derived bacterium of the genus Streptomyces. J Org Chem. 2007;72(2):323–330. doi: 10.1021/jo061064g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehr T, Kallen J, Oberer L, Sanglier JJ, Schilling W. Sanglifehrins A, B, C and D, novel cyclophilin-binding compounds isolated from Streptomyces sp. A92-308110. II. Structure elucidation, stereochemistry and physico-chemical properties. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1999;52(5):474–479. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.52.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Chen J, Wang H, Xie Y, Ju J, Yan Y. Structural analysis of HmtT and HmtN involved in the tailoring steps of himastatin biosynthesis. FEBS Lett. 2013;587(11):1675–1680. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang T, Wang Y, Yin J, Du Y, Tao M, Xu J, Chen W, Lin S, Deng Z. Identification and characterization of the pyridomycin biosynthetic gene cluster of Streptomyces pyridomyceticus NRRL B-2517. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(23):20648–20657. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.180000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa J, Hotta K. FramePlot: a new implementation of the frame analysis for predicting protein-coding regions in bacterial DNA with a high G + C content. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;174(2):251–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(17):3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansari MZ, Yadav G, Gokhale RS, Mohanty D. NRPS-PKS: a knowledge-based resource for analysis of NRPS/PKS megasynthases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(Web Server issue):W405–W413. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rausch C, Weber T, Kohlbacher O, Wohlleben W, Huson DH. Specificity prediction of adenylation domains in nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPS) using transductive support vector machines (TSVMs) Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(18):5799–5808. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gust BKT, Chater K. PCR targeting system in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) Norwich U K: The John Innes Foundation; 2002. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Electronic supplementary materials are available: bacterial strains (Table S1), plasmids (Table S2), primers (Table S3), and the substrate-specific codon sequences (Table S4); sequence alignment (Figures S1-6) and mutant construction (Schemes S1-8).