Abstract

Poor oral health is common in HIV+ adults. We explored the feasibility, acceptance and key features of a prevention-focused oral health education program for HIV+ adults. This was a pilot sub-study of a parent study in which all subjects (n=112) received a baseline periodontal disease (PD) examination and provider-delivered oral health messages informed by the Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills (IMB) Model. Forty-one parent study subjects were then eligible for the sub-study; of these subjects, a volunteer sample was contacted and interviewed 3–6 months after the baseline visit. At the recall visit, subjects self-reported behavior changes that they had made since the baseline. PD was re-assessed using standard clinical assessment guidelines and results were shared with each subject. At recall, individualized, hands-on oral hygiene coaching was performed and patients provided feedback on this experience. Statistics included frequency distributions, means and chi-square testing for bivariate analyses. Twenty two (22) HIV+ adults completed the study. At recall, subjects had modest, but non-significant (p>0.05) clinician observed improvement in PD. Each subject reported adopting, on average, 3.8 (± 1.5) specific oral health behavior changes at recall. By self-report, subjects attributed most behavior changes (95%) to baseline health messages. Behavior changes were self-reported for increased frequency of flossing (55%) and tooth-brushing (50%), enhanced tooth-brushing technique (50%), and improved eating habits (32%). As compared to smokers, non-smokers reported being more optimistic about their oral health (p=.024) at recall and were more likely to have reported changing their oral health behaviors (p=.009). All subjects self-reported increased knowledge after receiving hands-on oral hygiene coaching performed at the recall visit. In HIV+ adults, IMB-informed oral health messages promoted self-reported behavior change; subjects preferred more interactive, hands-on coaching. We describe a holistic clinical behavior change approach that may provide a helpful framework when creating more rigorously-designed IMB-informed studies on this topic.

Keywords: HIV, Oral Health, periodontal disease, Behavior Theory, prevention and communication

Introduction

HIV+ adults are at increased risk for poor oral health outcomes including tooth loss (Alves et al., 2006; Mulligan et al., 2004), gingival defects (Mulligan, et al., 2004), traditionally defined periodontal disease (McKaig et al., 1998; Vernon et al., 2009), dry mouth (xerostomia) (Nittayananta et al., 2010; Patton, Strauss, McKaig, Porter, & Eron, 2003; Reznik, 2005)and dental caries (Ram, Kumar, & Navazesh, 2011). Unmet dental needs are also high in this population(Freed et al., 2005; Heslin et al., 2001; Jeanty et al., 2012; Marcus et al., 2000), and underutilization of dental care services (Coulter et al., 2000; Marcus, et al., 2000; Shiboski et al., 2005; Vernon, et al., 2009) may further contribute to poor oral health outcomes. Greater attention to more effective, comprehensive dental care for persons living with HIV-infection is indicated (Badner, 2005; IOM, 2011; USDHHS, 2000).

Theoretical Framework

There is a general consensus that health promotion interventions should be driven by behavioral theory (Glanz & Bishop, 2010; Riddle & Clark, 2011). Patient education alone has had limited long-term success in changing oral health behaviors in adult populations (Renz, Ide, Newton, Robinson, & Smith, 2007). The Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills (IMB) Model has been successfully used to understand HIV-related sexual risk behavior and to construct interventions to change behavior across a wide range of settings, populations and time (Fisher JD, 2009), including interventions involving breast self-examination (Misovich, 2003), motorcycle safety (Fisher JD, 2009) and adherence to antiretroviral therapy (Fisher, Fisher, Amico, & Harman, 2006; Starace, Massa, Amico, & Fisher, 2006). The conceptual underpinnings of the IMB model are based on strong theory (Ajzen, 1980; Bandura, 1989, 1994; M. Fishbein, and Ajzen, I., 1975; M. Fishbein, and Middlestadt, S.E., 1989; Schifter & Ajzen, 1985).

We applied constructs of the IMB model (see Methods) to promote individualized oral health behavior changes. In delivering health messages, we also drew from self-determination theory (SDT) (Deci, 1985), communication tailoring (Noar, Benac, & Harris, 2007) and the spirit of motivational interviewing (MI) (W. R. Miller, and S. Rollnick 2002; W. R. Miller & Rollnick, 2009; Ramsier, 2010; Rollnick, 2007). To our knowledge, no previous studies have examined IMB-informed oral health behavior change in HIV+ adults; thus we investigated the feasibility, acceptance and key features of an IMB-informed oral health education program for HIV+ adults.

Methods

Overall Approach/Philosophy: personalized oral health communication

Our philosophy was central to our approach. Since interpersonal interaction may be the most critical factor to influence motivation and behavior change (Najavits, Crits-Christoph, & Dierberger, 2000; Najavits & Weiss, 1994), our goal was to be relational with each subject (Rollnick, 2007). Using a conversational approach can make a significant difference in terms of how suggestions are received (Salter, Holland, Harvey, & Henwood, 2007); thus, our communication style was open, flexible and conversational; however, interactions by one dentist were not audiotaped, so fidelity to this construct was not measured. We avoided a hierarchical patient-provider relationship and worked with or alongside the subject. Importantly, we acted as a patient advocate. Developing a deep bond of trust and support may, in itself, have therapeutic value in the health care setting (Scott et al., 2008; Scott, Scott, Miller, Stange, & Crabtree, 2009).

Overall, health messages were delivered in a coaching manner; we: 1) clinically evaluated each subject’s periodontal disease; 2) assessed behavioral causes, asking questions to gauge subject’s current knowledge and motivation; 3) evaluated the subject’s oral hygiene skill most proximal to the risk for their oral conditions—and accepted this as a starting point from which to work forward; finally, we 4) broke down new behaviors into small, manageable changes (Bandura, 1998)–i.e., those most likely to positively impact one’s oral health.

Study Design

Visit 1 (Baseline): Periodontal Disease Examination and Oral Health Message Delivery

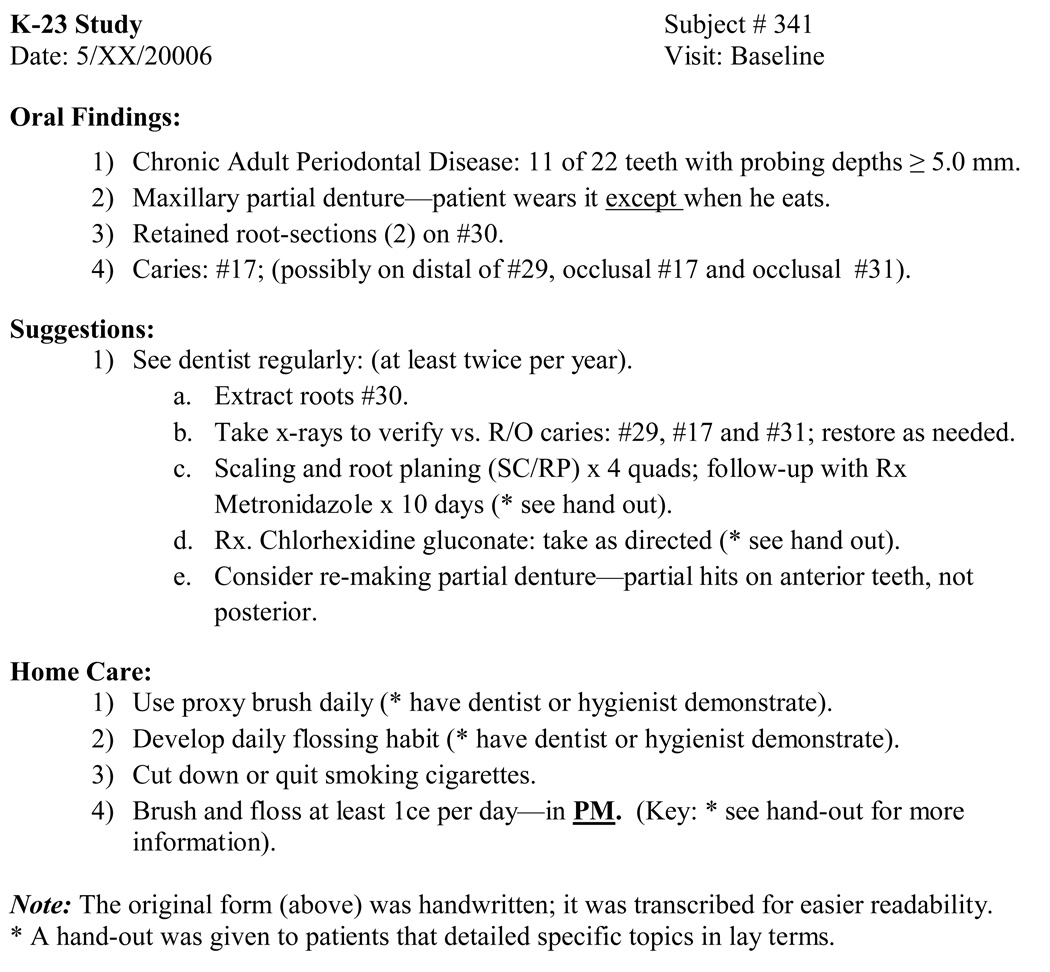

This was a pilot sub-study of a parent study (Vernon, et al., 2009) of 112 HIV+ adult volunteers. The parent study included HIV+ adults (age 18 or older), who did not have cardiovascular disease, cancer or diabetes; all subjects had 20 or more teeth. This study was approved by the University Hospitals Case Medical Center’s Institutional Review Board; all subjects gave Informed Consent. At study Visit 1 (baseline), we performed an oral examination including complete periodontal probing at six sites per tooth as previously described (Vernon, et al., 2009). Each participant received from the same dentist a verbal explanation and hand-written document of clinical findings and suggestions (see Figure 1); this health message delivery from one dentist lasted approximately 20–40 minutes. Study subjects were seen from May 2005 through August 2006.

Figure 1.

Example of Written Baseline Oral Health Message

Visit 2 (Recall): Interview and Periodontal Re-Examination

Of 41 eligible subjects, 22 HIV+ adults agreed to participate in the pilot study recall (Visit 2), 3–6 months after baseline. At visit 2, subjects were interviewed by one dentist (LTV) using a semi-structured questionnaire to assess behavior changes made after Visit 1. A periodontal disease re-examination was completed in the dental clinic by one dentist (Vernon, et al., 2009); because of time constraints and our definition of PD, only those tooth sites with a baseline clinical attachment level (CAL) ≥ 4.0 mm were re-probed; change in PD was determined as the percent of re-examined sites that improved (CAL of <4.0 mm), worsened (CAL >5.0 mm) or showed no change (CAL=4.0 mm). Next, individualized hands-on oral hygiene instructions were delivered; afterwards, subjects were asked to comment on this instruction. At both study visits, no restorative dental care was provided and subjects were nominally compensated.

Data Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (V14.0), and included frequency distributions, determination of mean values, and chi-squared testing for bivariate analyses

Results

Twenty two (22) HIV+ adults completed the study. Table 1 lists cohort characteristics. The mean duration of time from baseline to recall visit was 5.9 (±2.2) months. On average, at recall, 38 discrete periodontal sites with CAL ≥4.0 mm per subject were re-probed by one dentist; each subject, on average, had 41% of examined sites that improved, 33% of sites worsened and 26% of sites remained unchanged. While clinical measures of PD improved modestly, improvements were not statistically significant (p>0.05) nor associated with receiving outside dental care, or changes in attitude or oral health behaviors (data not shown).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics of 22 HIV+ Adults at Baseline Visit

| Variable | Mean (±SD) | Percent | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age (years) | 42.6 (6.9) | 22 | |

| Male | 77% | 17 | |

| Black/African American | 77% | 17 | |

| Education ≥some college | 59% | 13 | |

| Receiving Medicaid/Medicare, RW | 82% | 18 | |

| Medical Characteristics | |||

| Living with HIV (years) | 12.2 (6.4) | 21 | |

| Time on HAART (years) | 4.4 (3.0) | 20 | |

| Nadir CD4+T cell count | 183.7 (179.0) | 22 | |

| CD4+ T cell count (cells/µl) | 501.8 (353.9) | 22 | |

| HIV RNA (log copies/mL) | 2.2 (1.7) | 22 | |

| HIV RNA (≤50 copies/mL) | 68% | 15 | |

| Oral Health Characteristics | |||

| Clinical measures of periodontal disease (**) | |||

| PPD≥5mm | 43.3 (21.2) | 22 | |

| REC>0mm | 63.0 (19.6) | 22 | |

| CAL≥3mm | 74.3 (21.2) | 22 | |

| Floss all teeth >1 time per week | 45% | 10 | |

| Ever smoked | 72% | 16 | |

| Currently smoke | 45% | 10 | |

| Did not visit dentist in past year | 50% | 11 | |

| Number dental visits in past 5 years | 2.0 (0.8) | 22 | |

| Reported dry mouth (xerostomia) | 45% | 10 | |

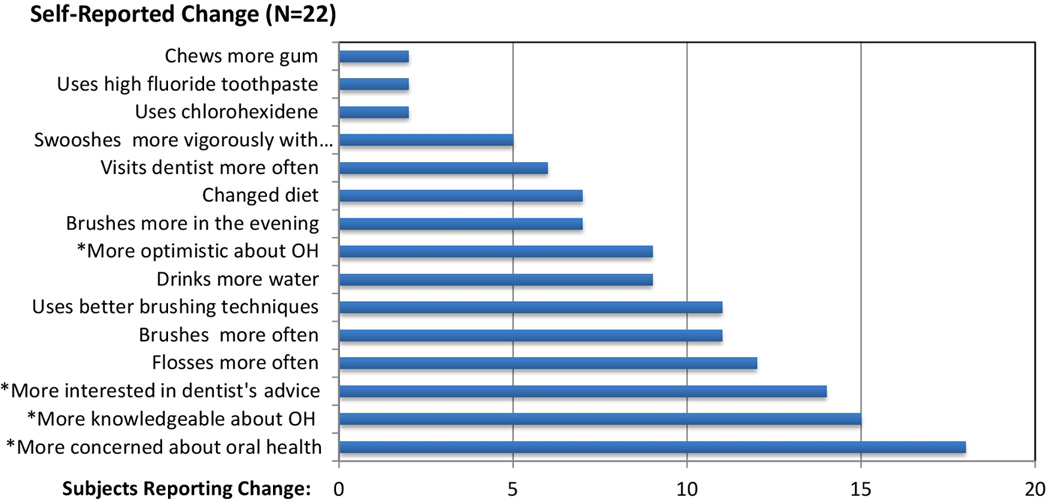

On average, subjects self-reported making a mean of 3.8 (1±.5) specific oral health-related behavior changes after receiving the baseline oral health messages. At recall, as per self-report, most subjects (95%) attributed their specific oral health behavior changes at least in part to the baseline oral health message delivery. Figure 2 lists specific changes made. As compared to smokers, non-smokers self-reported being more optimistic about their oral health (p=.024) at recall and were more likely to have changed their oral health behaviors (p=.009). All participants self-reported increased knowledge after receiving individualized hands-on oral hygiene skills coaching at recall. Between baseline and recall, 59% of subjects self-reported visiting a dentist with18% receiving periodontal disease treatment (scaling and root planning).

Figure 2.

Frequency of Self-Reported Changes Following IMB-Informed Oral Health Message (N=22)

Oral hygiene (OH).

* Note: Changes with asterisk are not included in the calculation of specific oral health behavior changes.

Discussion

In this study, prevention-focused, individualized oral health message delivery was feasible and well accepted. Clinician-observed clinical improvement over time in PD was not associated with seeing the dentist, improved attitudes or changes in oral health behavior. Improvement in PD typically requires scaling and root planing (SC/RP) in addition to effective home hygiene, and, in this study, relatively few (18%) received SC/RP between the baseline and recall visit. Further, having re-probed only sites with CAL≥4.0 mm, we may not have detected more subtle changes in PD or gingivitis that may have occurred. It is also possible that sites with CAL<4.0 mm may have worsened. Measuring changes over time in bleeding on probing may have also been more useful to detect short-term PD-related changes.

As per self-report, HIV+ adults made specific oral health-related behavior changes following health message delivery. The self-reported increase in knowledge after hands-on coaching at recall may indicate that individualized skill training is an important focus for future studies.

Our self-reported findings are consistent with theory-driven published longitudinal reports. Outside of HIV+ cohorts, Weinstein et al, 2006 reported that MI-based approaches with mothers reduced tooth decay in their children (Weinstein, Harrison, & Benton, 2006) and a self-determination theory-based approach by Munster Halvari et al, 2012 reduced dental plaque and gingivitis. (Munster Halvari, Halvari, Bjornebekk, & Deci, 2012) Kakudate et al, 2009 applied a cognitive behavioral approach to enhance self-efficacy and lower plaque index in a 3-week study in adults with PD (Kakudate, Morita, Sugai, & Kawanami, 2009).

Our interaction style drew off of self-determination theory (Deci, 1985) and motivational interviewing (Rollnick, 2007). Although unmeasured, the manner in which messages were delivered was an important aspect of our approach.

This study has a number of strengths. It was holistic and innovative; we applied the Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills Model to oral health behavior change in HIV+ adults with some promising results. Oral health message delivery was feasible. We outline an approach that was personalized to and well received by HIV+ adults. In our study, IMB-informed communication was effective in promoting self-reported oral health behavior change after one patient-provider interaction.

This study also has several limitations. The sample size is small (N=22) and our volunteer group may be prone to selection bias; recall participants may have been more likely to report behavior changes than those not recalled. We had no control group to which results from the group receiving IMB-informed health messages could be compared. We measured oral health behavior changes over time with self-report, which can be unreliable and prone to overestimation (Shi et al., 2010) and social desirability biases. Our follow-up period was relatively short. Finally, key constructs from the IMB model were globally operationalized, not directly measured; thus, fidelity to IMB theory cannot be determined.

Future studies require a reliable and valid measure of oral hygiene skill (i.e., tooth brushing, flossing and proxy brush use) —a central construct of our IMB-informed model—and would enable more rigorous future investigation.

HIV+ adults can present to outpatient dental settings with arguably some of the most complex, dynamic and challenging oral health concerns. Poor oral health can negatively impact an HIV+ patient’s quality of life (Cherry-Peppers, Daniels, Meeks, Sanders, & Reznik, 2003). Findings from this study suggest that prevention-focused approaches in addition to routine dental care may promote more optimal oral health in HIV+ adults.

Acknowledgements

We especially thank all of our research participants. NIDCR K23 DE15746 and R21 DE21376, Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) AI136219, Dahms Clinical Research Unit of the CTSA UL1 RR024989 and UM01 RR000080, and the Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative of Cleveland, UL1TR000439 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) component of the National Institutes of Health and NIH roadmap for Medical Research.

Footnotes

Meetings at which parts of data were presented: A poster of these data was presented at International Association of Dental Research (IADR) on March 23, 2007; 85th General Session and Exhibition of IADR; New Orleans, LA, USA.

The authors report that they do not have any conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Lance T. Vernon, Email: ltv1@case.edu, Department of Biological Sciences, Case Western Reserve University School of Dental Medicine, Cleveland, OH, USA.

Catherine A. Demko, Email: cad3@case.edu, Department of Community Dentistry, Case Western Reserve University School of Dental Medicine, Cleveland, OH, USA.

Allison R. Webel, Email: arw72@case.edu, Bolton School of Nursing, Case Western Reserve University.

Ryan M. Mizumoto, Email: rmizumoto@gmail.com, Department of Biological Sciences, Case Western Reserve University School of Dental Medicine, Cleveland, OH, USA.

References

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. New Jersey: Prentice Hall; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Alves M, Mulligan R, Passaro D, Gawell S, Navazesh M, Phelan J, et al. Longitudinal evaluation of loss of attachment in HIV-infected women compared to HIV-uninfected women. J Periodontol. 2006;77(5):773–779. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.P04039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badner VM. Ensuring the oral health of patients with HIV. J Am Dent Assoc. 2005;136(10):1415–1417. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2005.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Perceived self-efficacy in the exercise and control over AIDS infection. Newbery PArk, CA: Sage; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social congitive theory and exercise control of HIV infection. In: D RJ, Peterson JL, editors. Preventing AIDS: Theories and methods of behavioral interventions. New York, NY: Plenum; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Health promotion from the perspective of social cognitive theory. Psychology & Health. 1998;13(4):623–649. [Google Scholar]

- Cherry-Peppers G, Daniels CO, Meeks V, Sanders CF, Reznik D. Oral manifestations in the era of HAART. J Natl Med Assoc. 2003;95(2 Suppl 2):21S–32S. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter ID, Marcus M, Freed JR, Der-Martirosian C, Cunningham WE, Andersen RM, et al. Use of dental care by HIV-infected medical patients. J Dent Res. 2000;79(6):1356–1361. doi: 10.1177/00220345000790060201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deci EL, Ryan RM, editors. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behaviour. New York: Plenum Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Middlestadt SE. Using the theory of reasoned action as a framework for understanding and changing AIDS-related behaviors. In: A GW, Mays SFSVM, editors. Primary prevention of AIDS: Psychological approaches. London: Sage; 1989. pp. 93–110. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Amico KR, Harman JJ. An information-motivation-behavioral skills model of adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Health Psychol. 2006;25(4):462–473. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.4.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JD, F W, S P. The Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills Model of HIV Preventative Behavior. In: R C, Diclemente R.J KM, editors. Emerging Theories in Health Promotion Practice adn Research. Second ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; A Wiley Imprint; 2009. pp. 22–63. [Google Scholar]

- Freed JR, Marcus M, Freed BA, Der-Martirosian C, Maida CA, Younai FS, et al. Oral health findings for HIV-infected adult medical patients from the HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study. J Am Dent Assoc. 2005;136(10):1396–1405. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2005.0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K, Bishop DB. The role of behavioral science theory in development and implementation of public health interventions. Annu Rev Public Health. 2010;31:399–418. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heslin KC, Cunningham WE, Marcus M, Coulter I, Freed J, Der-Martirosian C, et al. A comparison of unmet needs for dental and medical care among persons with HIV infection receiving care in the United States. J Public Health Dent. 2001;61(1):14–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2001.tb03350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IOM. (Institute of Medicine). Advancing Oral Health in America. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Jeanty Y, Cardenas G, Fox JE, Pereyra M, Diaz C, Bednarsh H, et al. Correlates of Unmet Dental Care Need Among HIV-Positive People Since Being Diagnosed with HIV. Public Health Rep. 2012;127(Suppl 2):17–24. doi: 10.1177/00333549121270S204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakudate N, Morita M, Sugai M, Kawanami M. Systematic cognitive behavioral approach for oral hygiene instruction: a short-term study. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74(2):191–196. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus M, Freed JR, Coulter ID, Der-Martirosian C, Cunningham W, Andersen R, et al. Perceived unmet need for oral treatment among a national population of HIV-positive medical patients: social and clinical correlates. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(7):1059–1063. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.7.1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKaig RG, Thomas JC, Patton LL, Strauss RP, Slade GD, Beck JD. Prevalence of HIV-associated periodontitis and chronic periodontitis in a southeastern US study group. J Public Health Dent. 1998;58(4):294–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1998.tb03012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preapring people for Change. 2nd Ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Ten things that motivational interviewing is not. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2009;37(2):129–140. doi: 10.1017/S1352465809005128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misovich SJ, Martinez T, Fisher JD, Bryan AD, Catapano Breast self-examination: A test of the information, motivation, and behavioral skills model. Journal of Applied Social Sciences. 2003;(33):775–790. [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan R, Phelan JA, Brunelle J, Redford M, Pogoda JM, Nelson E, et al. Baseline characteristics of participants in the oral health component of the Women's Interagency HIV Study. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2004;32(2):86–98. doi: 10.1111/j.0301-5661.2004.00128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munster Halvari AE, Halvari H, Bjornebekk G, Deci EL. Self-determined motivational predictors of increases in dental behaviors, decreases in dental plaque, and improvement in oral health: a randomized clinical trial. Health Psychol. 2012;31(6):777–788. doi: 10.1037/a0027062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najavits LM, Crits-Christoph P, Dierberger A. Clinicians' impact on the quality of substance use disorder treatment. Subst Use Misuse. 2000;35(12–14):2161–2190. doi: 10.3109/10826080009148253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najavits LM, Weiss RD. Variations in therapist effectiveness in the treatment of patients with substance use disorders: an empirical review. Addiction. 1994;89(6):679–688. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb00954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nittayananta W, Talungchit S, Jaruratanasirikul S, Silpapojakul K, Chayakul P, Nilmanat A, et al. Effects of long-term use of HAART on oral health status of HIV-infected subjects. J Oral Pathol Med. 2010;39(5):397–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2009.00875.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Benac CN, Harris MS. Does tailoring matter? Meta-analytic review of tailored print health behavior change interventions. Psychol Bull. 2007;133(4):673–693. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton LL, Strauss RP, McKaig RG, Porter DR, Eron JJ., Jr Perceived oral health status, unmet needs, and barriers to dental care among HIV/AIDS patients in a North Carolina cohort: impacts of race. J Public Health Dent. 2003;63(2):86–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2003.tb03480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ram S, Kumar S, Navazesh M. Management of xerostomia and salivary gland hypofunction. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2011;39(9):656–659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsier C, editor. Health Behavior Change in Dental Practice. Ames, Iowa: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Renz A, Ide M, Newton T, Robinson PG, Smith D. Psychological interventions to improve adherence to oral hygiene instructions in adults with periodontal diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;2:CD005097. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005097.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reznik DA. Oral manifestations of HIV disease. Top HIV Med. 2005;13(5):143–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddle M, Clark D. Behavioral and social intervention research at the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) J Public Health Dent. 2011;71(Suppl 1):S123–S129. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2011.00216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollnick S, Miller WR, editors. Motivational Interviewing in Health Care. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Salter C, Holland R, Harvey I, Henwood K. "I haven't even phoned my doctor yet" The advice giving role of the pharmacist during consultations for medication review with patients aged 80 or more: qualitative discourse analysis. BMJ. 2007;334(7603):1101. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39171.577106.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schifter DE, Ajzen I. Intention, perceived control, and weight loss: an application of the theory of planned behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1985;49(3):843–851. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.49.3.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JG, Cohen D, Dicicco-Bloom B, Miller WL, Stange KC, Crabtree BF. Understanding healing relationships in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(4):315–322. doi: 10.1370/afm.860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JG, Scott RG, Miller WL, Stange KC, Crabtree BF. Healing relationships and the existential philosophy of Martin Buber. Philos Ethics Humanit Med. 2009;4:11. doi: 10.1186/1747-5341-4-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L, Liu J, Fonseca V, Walker P, Kalsekar A, Pawaskar M. Correlation between adherence rates measured by MEMS and self-reported questionnaires: a meta-analysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:99. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiboski CH, Cohen M, Weber K, Shansky A, Malvin K, Greenblatt RM. Factors associated with use of dental services among HIV-infected and high-risk uninfected women. J Am Dent Assoc. 2005;136(9):1242–1255. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2005.0340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starace F, Massa A, Amico KR, Fisher JD. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy: an empirical test of the information-motivation-behavioral skills model. Health Psychol. 2006;25(2):153–162. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USDHHS, U. D. o. H. a. H. S. Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S.: Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Vernon LT, Demko CA, Whalen CC, Lederman MM, Toossi Z, Wu M, et al. Characterizing traditionally defined periodontal disease in HIV+ adults. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2009;37(5):427–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2009.00485.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein P, Harrison R, Benton T. Motivating mothers to prevent caries: confirming the beneficial effect of counseling. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137(6):789–793. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]