Abstract

Periodontitis is a common dental disease which results in irreversible alveolar bone loss around teeth, and subsequent tooth loss. Previous studies have focused on bacteria that damage the host and the roles of commensals to facilitate their colonization. Although some immune responses targeting oral bacteria protect the host from alveolar bone loss, recent studies show that particular host defense responses to oral bacteria can induce alveolar bone loss. Host damaging and immunostimulatory oral bacteria cooperatively induce bone loss by inducing gingival damage followed by immunostimulation. In mouse models of experimental periodontitis induced by either Porphyromonas gingivalis or ligature, γ-proteobacteria accumulate and stimulate host immune responses to induce host damage. Here we review the differential roles of individual bacterial groups in promoting bone loss through the induction of host damage and immunostimulation.

Keywords: periodontitis, NOD1, pathobiont, innate immunity, alveolar bone absorption, neutrophil recruitment

Periodontitis is an oral disease associated with outgrowth of multiple bacteria and activation of host immunity

There is a paradox in the way our body handles microbes that live in the oral cavity. Most immune responses are beneficial in that they protect the host against invading pathogens. However, some immune responses to bacteria such as those associated with periodontitis can also damage the host by inducing significant pathology in the oral cavity. Periodontitis is a dental disease affecting billions of patients worldwide that is characterized by chronic gingival inflammation and subsequent alveolar bone loss around the teeth [1,2]. Although colonization of a single bacterium Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans is highly associated with aggressive periodontitis in young individuals and adults [3], multiple bacteria are typically involved in the development of chronic periodontitis that affect adult patients [4–7]. Culture-based studies in the last century showed marked changes of the oral bacterial populations during the development of periodontal disease and the important role of ‘red complex’ bacteria that include Porphyromonas gingivalis, Tannerella forsythia and Treponema denticola [4,7]. The difference in the oral bacterial community between healthy and periodontitis patients has been confirmed and characterized in more detail by non-culture based techniques [8–10]. The keystone bacteria that are recently found to be associated with periodontitis also include Filifactor alocis, Treponema, Prevotella, Selenomonas, Peptostreptococcus, Anaeroglobus, Desulfobulbus species, Lachnospiraceae, Synergistetes and TM7 species in addition to red complex bacteria [9,10]. Although these newly identified keystone pathogens have not been well characterized, a main feature of the red complex bacteria is the presence of a high level of protease activity. The proteases including P. gingivalis gingipains, T. forsythia PrtH and T. denticola dentilisin proteases are important for virulence [11–14]. The degradation of host extracellular matrix proteins by the bacterial proteases can result in loss of the epithelial barrier in the oral cavity [15,16] and a P. gingivalis strain lacking gingipains is impaired in its ability to induce loss of epithelial barrier [16]. Besides these red complex bacteria, other oral commensals play a significant role in periodontitis development. Previous studies with in vivo and in silico interaction assays focused extensively on metabolic and physical interactions of non-red complex and red complex bacteria and elucidated its importance for dysbiosis in eliciting periodontitis development [5,6,17,18].

Animal models reveal protective responses against periodontitis development

To determine the importance of individual oral bacteria in disease development, experimental animals including mice were infected with individual bacteria isolated from patients with periodontitis, and the sequence of host responses that result in alveolar bone loss [19,20]. Importantly, these animals possess their own commensals that can affect the infection. For example, when specific pathogen-free (SPF) mice are pre-treated with antibiotics such as sulphamethoxazole and trimethoprim which modify the composition of the murine oral microbiota, P. gingivalis can reproducibly colonize the oral cavity resulting in alveolar bone loss [21]. Likewise, animal models were used to analyze the interactions among bacteria by combinatory infection which revealed their functional interaction in inducing bone loss [22–24]. These infection models have also shown that host immune responses to oral bacteria are important for periodontitis development. For example, pre-immunization of SPF mice with P. gingivalis decreases P. gingivalis load and the level of alveolar bone loss after infection [13,25]. These observations suggest that adaptive host immunity is important for the elimination of harmful bacteria involved in periodontitis development and protective against alveolar bone loss. The finding that mice deficient in inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), P-selectin or intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM1)-depleted mice are susceptible to P. gingivalis -induced alveolar bone loss [26,27] (Figure 1), suggests that innate immune responses are also important for prevention of alveolar bone loss. Since innate immune systems including complement are critical for host resistance against various pathogens [28], it would be expected that host innate and adaptive immunity prevent periodontitis development through the elimination or control of host-damaging bacteria. However, recent studies have revealed that the mechanisms involved in periodontitis development are much more complex and that host immunity acts like a double edged sword as described below.

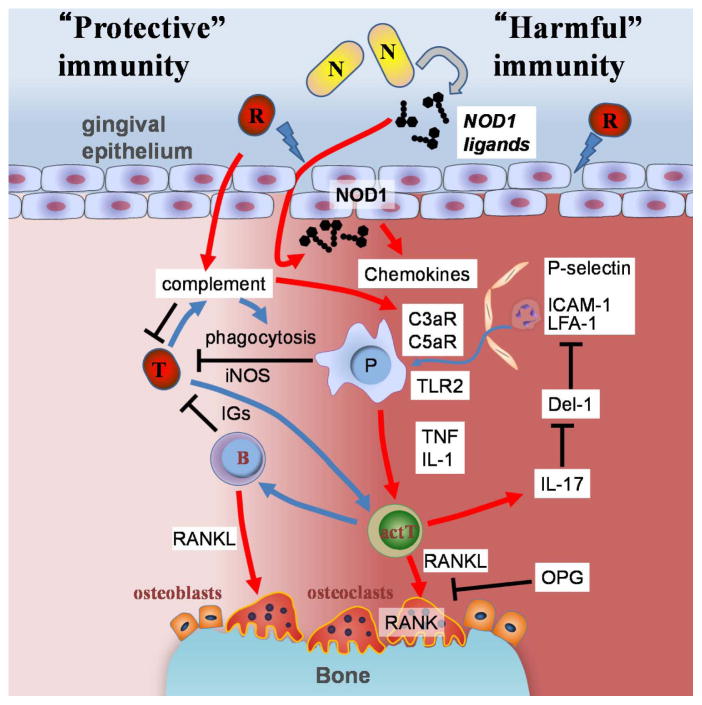

Figure 1. Models for host protective and damaging immune responses to oral bacteria in periodontitis.

Alveolar bone loss in periodontitis is primarily associated with immune responses to oral bacteria. The immune responses provide protection against translocated bacteria (T) but also mediate alveolar bone resorption which is harmful to host tissues. Host protective immune responses include elimination of pathogens by phagocytic cells (P) and production of antigen-specific immunoglobulin (IGs) which are mediated by antigen presenting phagocytic cells and activated T cells (actT). Inducible NO synthase (iNOS) is also known to be involved in host protective immune responses. The number of bone absorbing osteoclasts increase at sites below the damaged gingiva during periodontitis development. In the model, host damaging red complex bacteria (R) damage the epithelial barrier function. The epithelial damage allows the translocation of harmful bacteria or immunostimulatory bacterial components into the gingival tissue. NOD1 ligands are released from particular types of oral bacteria (N) which induces recruitment of phagocytotic cells to the damaged gingiva via induction of chemokines such as CXCLs and CCLs (e.g. IL-8 and CCL3, respectively). Translocated bacteria (T) are eliminated by phagocytosis and other mechanisms through recruited immune cells, bacterial opsonization, and complement activation. A red complex bacterium such as P. gingivalis possesses the ability to process complement factors. The processed complement factors further induce recruitment of myelomonocytic cells to the lesion. IL-17 inhibits expression of Del-1 that interferes with neutrophil adhesion and molecule-dependent neutrophil recruitment. Some myelomonocytic cells are major sources of immunostimulatory molecules which facilitate the development of secondary immune responses to the bacteria. Immunization against P. gingivalis is shown to protect hosts from alveolar bone loss. Myelomonocytic cells also release bone loss-inducing inflammatory cytokines, TNF and IL-1, upon bacterial stimulation of PRRs such as TLR2. RANKL is expressed on activated T, B cells and osteoblasts that are stimulated by these inflammatory cytokines, T cells, and is important for alveolar bone loss in experimental periodontitis models. Therefore, protective immune responses that are activated to eliminate translocated bacteria can also damage the host by the induction of alveolar bone loss.

Induction of inflammatory responses results in alveolar bone loss

In addition to protective immune responses that limit bacterial infection, immune responses that target oral bacteria can also result in local loss of alveolar bone. Alveolar bone loss in periodontitis is primarily due to increased bone resorption by osteoclasts that are activated by immunostimulation from oral bacterial components [29]. Differentiation of osteoclasts is also induced by RANK activation following sequential immune responses to oral bacterial components [30] (Figure 1). The importance of immune responses to bacterial components in alveolar bone loss is further supported by the requirement of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and interleukin-6 (IL-6), inflammatory molecules that are induced by bacterial stimuli and enhances inflammatory responses [31, 32]. RANK activation is controlled by two critical factors, the RANK ligand (RANKL) and the RANK inhibitor, osteoprotegerin (OPG), whose expression levels in activated CD4+ T cells, B cells and osteoblasts are regulated by the inflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and IL-1 [31,33–36]. The dominant source of RANKL may appear to be activated T and B cells, because SCID, β2-macrogloblin and RAG-1 deficient mice show a marked decrease of alveolar bone loss in the ligature model [31, 37]. The main sources of the inflammatory cytokines TNF and IL-1, in response to stimulatory bacterial molecules which are recognized by pattern-recognition receptors (PRR), are neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages (see Glossary) [38]. These phagocytic cells express innate immune receptors Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2), C3aR and C5aR at high levels and mice lacking these proteins exhibit reduction of alveolar bone loss in experimental periodontitis models [39–42]. C3aR and C5aR are the receptors for processed complement factors that are produced through activation of bacteria-stimulated classical and alternative complement pathways as well as the lectin-dependent pathway [28]. In addition, P. gingivalis can induce C3 and C5 processing by gingipains [43]. Activation of C3aR and C5aR in immune cells induces chemotactic migration of phagocytes similar to that induced via the receptors for CXCL and CCL chemokines that are secreted from gingival tissues in response to bacterial stimulation [28]. The migration of neutrophils from blood to stimulated gingival tissues also requires several adhesive molecules including ICAM-1 and lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 (LFA-1) whose interaction is controlled by Del-1, an IL-17 regulated protein [44]. Neutrophil recruitment to damaged gingival sites is also triggered by bacterial stimulation of NOD1 [37]. NOD1 is an innate immune receptor that mediates neutrophil recruitment by inducing the secretion of chemokines from non-hematopoietic cells [45,46]. Mice lacking NOD1 show decreased chemokine CXCL1 secretion from the gingival epithelium in a ligature-induced model of periodontitis [37]. Thus, signaling via the innate immune receptors TLR2, NOD1, C3aR and C5aR connect oral bacteria to alveolar bone loss. While these innate immune receptors are important for elimination of invasive pathogens, their role in protective immune responses during inflammation-induced bone loss is still unknown. As stimulation of either NOD1 or C3aR/C5aR induces the recruitment of phagocytic immune cells, they might play synergistic and cooperative roles in the recruitment of cells. Indeed, C3a and C5a enhance TLR-dependent cytokine production in vivo [40]. Because stimulation of TLR2, but not NOD1, C3aR and C5aR alone, induces TNF and IL-1 production from immune cells, TLR2 might be important for the induction of the inflammatory cytokines downstream of NOD1, C3aR and C5aR. Clearly, additional studies are needed to understand the role of individual host factors in periodontitis.

Experimental periodontitis models have dissected the distinct roles of individual bacterial groups in periodontitis development

P. gingivalis-monocolonized mice, unlike P. gingivalis-colonized SPF mice, do not develop periodontitis phenotypes [47]. This indicates that P. gingivalis alone is insufficient to induce periodontitis and induction of alveolar bone loss requires additional oral bacteria. Moreover, the studies suggest that beside their impact on facilitating the colonization of host damaging bacteria such as P. gingivalis, other bacteria play synergistic roles with keystone pathogens to induce alveolar bone loss. Bacteria-independent gingival damage induced by ligature placement around or between the molars of SPF mice results in alveolar bone loss, whereas germ-free rodents do not develop bone loss when their teeth are ligated [37, 48]. So bone loss induced by ligature placement is also dependent on the oral bacteria and this model allows dissecting two different roles of oral bacteria in the induction of bone loss: a direct role through the immunostimulation [37] and an indirect role through the colonization of host damaging bacteria. Further analyses with mice lacking PRRs have elucidated differential immunostimulation by individual bacteria.

Individual oral bacteria possess different immunostimulatory activity

Recent studies have revealed that oral bacterial species possess different levels of immunostimulatory activities that can explained by distinct structure, amounts and localization of the bacterial immunostimulatory molecules [37,46,49–50] (Table 1). A. actinomycetemcomitans, a causal agent of aggressive periodontitis, is a γ-proteobacterium that produces lipopolysaccharide (LPS) with the highly TLR4-stimulatory moiety, diphospho-type lipid A [49,51]. TLR4 is critical for elimination of A. actinomycetemcomitans [52]. Although practically all bacteria express di-acyl and tri-acyl lipoproteins which are the ligands of TLR2/TLR6 and TLR2/TLR1, respectively [53], NOD1 ligands are quite unique in that they are small molecules that are released from particular bacteria [46,54] and stimulate non-hematopoietic cells upon loss of the epithelial barrier in the intestine and oral cavity [37,55]. Because NOD1 ligands are related to meso-diaminopimelic acid (mDAP)-type peptidoglycan that does not exist in many oral bacteria including Fusobacterium and Streptococcus, only particular groups of bacteria stimulate NOD1 [46,56]. Bacteroidetes species including P. gingivalis possesses low level of NOD1-stimulatory activity, although they produce mDAP-type peptidoglycan [37,46,57]. However, Pasturellaceae species A. actinomycetemcomitans and the related mouse commensal NI1060 possess and release peptidoglycan with high NOD1-stimulatory activity which is critical for induction of alveolar bone loss [37]. The different levels of NOD1-stimulatory activity released from individual bacteria is dependent on recycling and degradation pathways of peptidoglycan, because dominant NOD1 ligands are produced by peptidoglycan-cleaving enzymes [46,58–60].

Table 1.

Examples of bacteria that possess different immunostimulatory activity

| Phylum | Order(/family) | PRR ligandsa

|

Complement resistancec | Representatives | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TLR2b | TLR4 | NOD1 | NOD2 | ||||

| Proteobacteria | Enterobacteriales | + | + | + (2) | + (2) | + | Escherichia coli, Shigella flexneri |

| Pasteurellales | + | + | ++d (2) | +/− (2) | + | Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, NI1060 | |

| Pseudomonales | + | (−) | + (2) | +/− (2) | + | Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Pseudomonas putida, Morexella catarrhalis | |

|

| |||||||

| Bacteroidales | + | (−) | +/− (3) | +/− (3) | + | Porphyromonas gingivalis, Bacteroides flagilis, Bacteroides vulgatus, Tannerella forsythia | |

|

| |||||||

| Bacterodetes Firmicutes | Bacillales/Bacillaceae | + | − | ++ (5) | + (5) | Bacillus spp. | |

| Bacillales/Listeriaceae | + | − | +/−(1) | +/− (1) | + | Listeria monocytogenes. | |

| Bacillales/Staphylococcaceae | + | − | − | +/− (2) | + | Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermis | |

| Lactobacillales | + | − | − | +/− (6) | + | Streptococcus spp., Enterococcus spp., Lactobacillus spp. | |

| Clostridiales/Peptostreptococcaceae | + | − | ++ (1) | +/− (1) | Clostridium difficile | ||

| Clostridiales/Clostridiaceae | + | − | − (1) | +/− (1) | Clostridium tetani | ||

|

| |||||||

| Spirochaetes | Spirochaetales | + | − | nte | nt | Treponema denticola | |

|

| |||||||

| Fusobacteria | Fusobacteriales | + | + | +/− (1) | +/− (1) | Fusobacterium nucleatum | |

|

| |||||||

| Actinomyces | Actinomycetales | + | − | ++ (3) | +/− (1) | Propionibacterium acnes, Streptomyces spp. | |

According to [46,50]. Symbols: −, no ligand; (−), <1/100 stimulatory activity when compared with the E. coli K12 standard and for TLR4 this includes mono phospho lipid A type LPS [46,51,63]; −, no ligand activity; +/−, >5 and 2 ×109 kU/CFU for NOD1 and NOD2, respectively; +, >100, 10, and 5 kU/109 CFU for TLR4, NOD1 and NOD2, respectively; ++, >20kU/109 CFU for NOD1. The number of bacterial species whose individual PRR stimulatory activity have been determined are listed afterwards in parentheses.

Predicted from the genomic sequences of representative species.

Known to have resistant strains for complement activation and/or immunization (+) [67]. Listeria species are intracellular pathogens and therefore resistant to complement activation.

Some Actinomycetales species possess non-mesoDAP type pepidoglycan, so they lack high NOD1 stimulatory activity [62].

Not tested.

Bacteria produce multiple immunostimulatory molecules that may function as redundant stimuli. Injection of LPS preparations including γ-proteobacteria and P. gingivalis into the gingival tissue induces alveolar bone loss [61,62]. However, TLR4 is dispensable for induction of alveolar bone loss in the ligature-induced periodontitis model, although the dominant bacterium NI1060 is one γ-proteobacteria that possesses highly TLR4-stimulatory diphospho lipid A LPS (Table 1) [37,49]. This might be explained by the relatively low sensitivity of gingival cells to LPS in vivo and in situ [37]. However, LPS preparations of Bacteroidetes species including P. gingivalis that effectively induce alveolar bone loss [61,62], possess LPS molecules that contain the monophospho-type lipid A motif that poorly stimulate TLR4 ascompared with diphospho-type lipid A LPS [49, 63]. Indeed, TLR4-deficient and wild-type mice show similar levels of P. gingivalis load after subcutaneous infection [64]. Purified LPS preparations are often contaminated with other immunostimulatory molecules such as lipoproteins and peptidoglycan fragments that serve as ligands of TLR2 and NOD1, respectively [65,66]. Thus, the ability of LPS preparations to induce bone loss should be verified by the use of synthetic molecules that are free from contamination with other PRR ligands [63,66]. By infecting SPF mice with P. gingivalis, TLR2, C3aR and C5aR were shown to be important for immune responses that results in alveolar bone loss [39–42]. However, P. gingivalis-infected mice contain multiple γ-proteobacteria in the oral cavity [47]. Because P. gingivalis can induce alveolar bone loss by promoting synergistic interactions between complement and TLRs in vivo [40], it is possible that stimulation of other PRRs such as NOD1 is triggered by coexisting mouse commensals. Further analyses using germ-free mice lacking specific PRRs colonized with individual oral bacteria are required to understand the role of individual PRRs in periodontitis. It is also known that bacteria have different sensitivity to complement-mediated immunity [67]. For example, capsular polysaccharides and O structures of LPS confer resistance against both classical and alternative complement pathways. Moreover, many oral bacteria including P. gingivalis possess the ability to interfere with complement systems [28,67]. Therefore, it is possible that the bacterial composition affects activation of C3a- and C5a-mediated pathways in the oral cavity.

The distinct roles of host-damaging and immunostimulatory bacteria in periodontitis

The low NOD1-immunostimulatory activity of red complex bacteria led to the hypothesis that periodontitis development requires both host damage and immunostimulation. In this model, translocation of bacterial components such as NOD1 ligands is triggered by loss of the epithelial barrier that is caused by host damaging red complex (Figure 1). Accumulation of bacteria that possess a high potential to stimulate host immune responses during or after the loss of the epithelial barrier appear to be important for alveolar bone loss. Healthy adult mice have no significant NOD1-stimulatory activity in the oral cavity as the dominant bacteria are largely non-NOD1-stimulatory [57]. Subversion of host immunity by keystone pathogens and other members of the oral microbiota promotes the accumulation of immunostimulatory pathobionts and establishment of dysbiosis that results in alveolar bone loss [2,6,47] (Figure 2). Thus, keystone pathogens can avoid host immune responses and by doing so they promote the accumulation of pathobionts that induce host immune responses that are responsible for pathological alveolar bone loss. Accumulation of NOD1-stimulatory NI1060 by bacteria-independent gingival damage is critical for alveolar bone loss in the mouse ligature-induce periodontitis model [37]. NI1060 is a species related to A. actinomycetemcomitans - and A. actinomycetemcomitans also possesses high NOD1 stimulatory activity, suggesting that A. actinomycetemcomitans-mediated alveolar bone loss in humans is also mediated by NOD1. Therefore, microbiota transition induced by host damage is also important and results in accumulation of NOD1-stimulatory activity in the oral cavity. However, the kinetics of NOD1-stimulatory activity in the oral cavity of periodontitis patients is unknown. Taxonomic classification of oral bacteria suggests that particular bacteria in the non-red color complex might possess high immunostimulatory activity which is important for alveolar bone loss (Table 1). The importance of the pre-existence of immunostimulatory bacteria before colonization of host damaging bacteria has been reported in other disease models. For example, the intestinal microbiota already contains high numbers of γ-proteobacterial commensals that possess immunostimulatory activity, and loss of epithelial barrier by a host damaging bacterium triggers the translocation of immunostimulatory commensals [55]. Therefore, it is possible that immunostimulatory bacteria might preexist prior to accumulation of host damaging red complex bacteria in humans during periodontitis development.

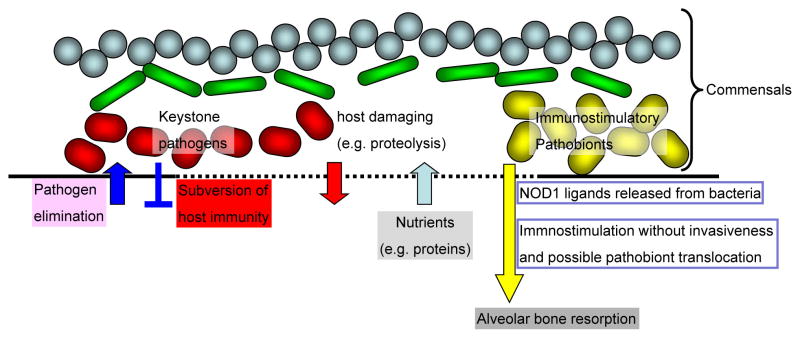

Figure 2. Distinct roles of host damaging and immunostimulatory bacteria in the development of periodonditis.

As shown in Figure 1, host immune responses to oral bacteria are critical for periodontitis development. A particular group of periodontitis-associated keystone pathogens possess the ability to subvert and escape recognition by the host immune system via several mechanisms including intracellular invasion and blockage of host immune signaling [70]. The latter events are likely important for keystone pathogens to establish a dysbiotic bacterial community by avoiding their elimination in the oral cavity. In addition, another type of commensal bacteria is recognized by the host innate immune system to elicit inflammatory responses that result in bone loss. NOD1 ligands are immunostimulatory molecules that are released from bacteria and therefore they can stimulate immune responses remotely from the bacteria. Thus, a model is proposed by which two distinct bacterial groups, namely host damaging (keystone pathogens) and immunostimulatory such as NOD1-stimulatory bacteria act synergistically to induce periodontitis. In the model, keystone pathogens possess the ability to induce damage to the epithelial barrier via virulence factors such as proteases (red complex bacteria) and/or toxins (A. actinomycetemcomitans) which enable immunostimulatory bacterial molecules such as NOD1 ligands and/or bacteria to translocate deeper into the tissue and to elicit inflammatory responses and bone loss.

Importantly, recent studies suggest a model in which two bacterial functions, namely host damage and immunostimulation act synergistically to induce periodontitis. In this model, the role of host damaging bacteria is to promote the translocation of immunostimulatory bacteria or bacterial components that result in alveolar bone loss. In the hypothesis, A. actinomycetemcomitans is a unique bacterium. Inoculation of A. actinomycetemcomitans alone induces alveolar bone loss in the SPF mouse model, whereas mouse NI1060 requires host damage to induce alveolar bone loss [37,52,68]. A. actinomycetemcomitans produces leukotoxin that damages host cells [3,69]. Therefore, A. actinomycetemcomitans is capable of inducing tissue damage in the oral cavity and providing immunostimulation via NOD1, although further investigation using A. actinomycetemcomitans-monoclonized mice is required to conclude that these two distinct functions of A. actinomycetemcomitans are sufficient to induce alveolar bone loss. This dual function of A. actinomycetemcomitans might explain why accumulation of A. actinomycetemcomitans alone is sufficient to induce aggressive periodontitis [3]. The latter notion is also supported by the fact that particular strains (e.g. JP2) which produce high amounts of host cell-damaging leukotoxin are more tightly associated with aggressive periodontitis [69]. Importantly, culture and non-culture based studies demonstrate that Aggregatibacter species are also preferentially found in some chronic periodontitis patients [4,9]. Therefore, in the presence of host damaging red complex bacteria, A. actinomycetemcomitans strains that secrete lower amounts of leukotoxin are possible sources of NOD1 ligands and may stimulate host immunity. It will be interesting to test if Aggregatibacter strains are involved in the development of chronic periodontitis and whether strains isolated from patients with chronic and aggressive periodontitis have different levels of leukotoxin that correlate with disease severity.

Concluding remarks

As described above, several innate immune receptors including TLR2, TLR4, NOD1, C3aR, and C5aR have been identified to be important for alveolar bone loss in mouse models. However, the etiology of human periodontitis is more complex and the roles of these innate immunity genes in human periodontal disease have not been addressed yet (Box 1). Host damaging bacteria that produce high levels of proteases and gingival damage are taxonomically diverse (Bacteroidetes and Spirochaetes). Likewise, bacteria that possess high levels of NOD1-stimulatory activity as well as bacteria that are resistant against complement are diverse [46, 55, 67]. A better understanding of the roles of individual bacteria in human periodontitis and their immunostimulatory functions should lead to better therapies for periodontitis patients. In particular, identification of NOD1-stimulatory bacteria in the human oral cavity would be helpful in understanding the role of immunostimulatory activity in patients with periodontitis. Although NOD1 is a cytosolic protein, NOD1-stimulatory bacteria in the oral cavity are not necessarily intracellular pathogens or pathobionts. Previous studies showed that NOD1 signaling can be initiated by extracellular administration of ligands or by mutant strains of Listeria monocytogenes that cannot enter the host cytosol [46]. Comprehensive analyses of PRR-specific immunostimulatory activity in individual oral bacteria should provide insight into how individual bacteria affect and modulate host responses that result in alveolar bone loss.

Box 1. Outstanding questions.

How do host immune responses to oral bacteria induce alveolar bone loss in periodontitis?

What is the molecular basis by which individual oral bacteria stimulate different host immune receptors?

Why are another type of pathobionts that stimulate host immunity required for periodontitis development?

Finally, colonization and accumulation of immunostimulatory bacteria that cause alveolar bone loss may depend, at least in part, on the presence of non-red complex commensals in addition to red complex bacteria. Therefore, investigation of the interactions between immunostimulatory bacteria and other commensals in the oral cavity should provide novel insight into the mechanism by which microbiota transition affects periodontitis development.

Highlights.

The host mounts beneficial and harmful immune responses to oral bacteria.

Innate immune receptors have a critical role in alveolar bone resorption.

Host damaging and immunostimulatory bacteria have different roles in periodontitis development.

Individual oral bacteria have different immunostimulatory activity.

Acknowledgments

The studies in the authors’ laboratory are funded by grant R01 DE018503 from the National Institutes of Health. We thank Gabriel Núñez and Aaron Burberry for critical review of the manuscript.

Glossary

- Alveolar bone

is a specialized type of bone which is designed to accommodate teeth. This type of bone is found in the lower and upper part of the jaw. Alveolar bone is thick and dense so that it can provide adequate support for the teeth

- Commensals

microbes that can colonize hosts without the induction of tissue damage or disease. Humans harbor trillions of commensals with >10,000 bacterial species of which about 700 bacterial species are residents in the oral cavity. Many commensals live in a mutually beneficial relationship with the host and benefit the host through several mechanisms including digestion of complex carbohydrates, immumomodulation, and resistance to pathogen colonization

- Pathobionts

some commensals can induce disease under particular conditions and are referred as pathobionts

- Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs)

are proteins that recognize unique and conserved molecular patterns, which are expressed by microbes. PRRs include membrane located Toll-like receptors (TLRs), C-type lectin-like receptors (CLRs), intracellular NOD-like receptors (NLRs), and RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs). For example, NOD1 recognizes the iE-DAP moiety of peptidoglycan-related small molecules and TLR4 recognizes the diphospho-type lipid A moiety in lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Stimulation of PRRs results in the activation of inflammatory transcription factors such as NF-κB and AP-1 through IKK and ERK/p38 MAPK, respectively, which induces the expression of many inflammatory proteins including cytokines and chemokines. In addition, certain PRRs activate interferon regulatory factors that induce interferon-dependent protective immune responses

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Eke PI, et al. Prevalence of periodontitis in adults in the United States: 2009 and 2010. J Dent Res. 2012;91:914–920. doi: 10.1177/0022034512457373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Darveau RP. Periodontitis: a polymicrobial disruption of host homeostasis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:481–490. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henderson B, et al. Aggregatibacter (Actinobacillus) actinomycetemcomitans: a triple A* periodontopathogen? Periodontol 2000. 2010;54:78–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2009.00331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Socransky SS, et al. Microbial complexes in subgingival plaque. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25:134–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1998.tb02419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kolenbrander PE, et al. Oral multispecies biofilm development and the key role of cell–cell distance. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:471–480. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hajishengallis G, Lamont RJ. Beyond the red complex and into more complexity: the polymicrobial synergy and dysbiosis (PSD) model of periodontal disease etiology. Mol Oral Microbiol. 2012;27:409–419. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-1014.2012.00663.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Darveau RP, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis as a potential community activist for disease. J Dent Res. 2012;91:816–820. doi: 10.1177/0022034512453589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paster BJ, et al. Bacterial diversity in human subgingival plaque. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:3770–3783. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.12.3770-3783.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Griffen AL, et al. Distinct and complex bacterial profiles in human periodontitis and health revealed by 16S pyrosequencing. ISME J. 2012;6:1176–1185. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abusleme L, et al. The subgingival microbiome in health and periodontitis and its relationship with community biomass and inflammation. ISME J. 2013;7:1016–1025. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saito T, et al. Cloning, expression, and sequencing of a protease gene from Bacteroides forsythus ATCC 43037 in Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4888–4891. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.11.4888-4891.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Brien-Simpson NM, et al. Role of RgpA, RgpB, and Kgp proteinases in virulence of Porphyromonas gingivalis W50 in a murine lesion model. Infect Immun. 2001;69:7527–7534. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.12.7527-7534.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gibson FC, et al. Prevention of Porphyromonas gingivalis-induced oral bone loss following immunization with gingipain R1. Infect Immun. 2001;69:7959–7963. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.12.7959-7963.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bamford CV, et al. The chymotrypsin-like protease complex of Treponema denticola ATCC 35405 mediates fibrinogen adherence and degradation. Infect Immun. 2007;75:4364–4372. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00258-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katz J, et al. Characterization of Porphyromonas gingivalis-induced degradation of epithelial cell junctional complexes. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1441–1449. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1441-1449.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Groeger S, et al. Effects of Porphyromonas gingivalis infection on human gingival epithelial barrier function in vitro. Eur J Oral Sci. 2010;118:582–589. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2010.00782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuramitsu HK, et al. Interspecies interactions within oral microbial communities. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2007;71:653–670. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00024-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mazumdar V, et al. Metabolic network model of a human oral pathogen. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:74–90. doi: 10.1128/JB.01123-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Madden TE, Caton JG. Animal models for periodontal disease. Methods Enzymol. 1994;235:106–119. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)35135-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graves DT, et al. The use of rodent models to investigate host-bacteria interactions related to periodontal diseases. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35:89–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01172.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baker PJ, et al. Oral infection with Porphyromonas gingivalis and induced alveolar bone loss in immunocompetent and severe combined immunodeficient mice. Arch Oral Biol. 1994;39:1035–1040. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(94)90055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Polak D, et al. Mouse model of experimental periodontitis induced by Porphyromonas gingivalis/Fusobacterium nucleatum infection: bone loss and host response. J Clin Periodontol. 2009;36:406–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2009.01393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Daep CA, et al. Structural dissection and in vivo effectiveness of a peptide inhibitor of Porphyromonas gingivalis adherence to Streptococcus gordonii. Infect Immun. 2011;79:67–74. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00361-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Settem RP, et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum and Tannerella forsythia induce synergistic alveolar bone loss in a mouse periodontitis model. Infect Immun. 2012;80:2436–2443. doi: 10.1128/IAI.06276-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gibson FC, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis-specific immunoglobulin G prevents P. gingivalis-elicited oral bone loss in a murine model. Infect Immun. 2004;72:2408–2411. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.4.2408-2411.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fukada SY, et al. iNOS-derived nitric oxide modulates infection-stimulated bone loss. J Dent Res. 2008;87:1155–1159. doi: 10.1177/154405910808701207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baker PJ, et al. Adhesion molecule deficiencies increase Porphyromonas gingivalis-induced alveolar bone loss in mice. Infect Immun. 2000;68:3103–33107. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.6.3103-3107.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ricklin D, et al. Complement: a key system for immune surveillance and homeostasis. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:785–797. doi: 10.1038/ni.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sveen K, Skaug N. Bone resorption stimulated by lipopolysaccharides from Bacteroides, Fusobacterium and Veillonella, and by the lipid A and the polysaccharide part of Fusobacterium lipopolysaccharide. Scand J Dent Res. 1980;88:535–542. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1980.tb01264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kikuchi T, et al. Cot/Tpl2 is essential for RANKL induction by lipid A in osteoblasts. J Dent Res. 2003;82:546–550. doi: 10.1177/154405910308200712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baker PJ, et al. CD4+ T cells and the proinflammatory cytokines gamma interferon and interleukin-6 contribute to alveolar bone loss in mice. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2804–2809. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.6.2804-2809.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tanaka T, et al. Targeting interleukin-6: all the way to treat autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Int J Biol Sci. 2012;8:1227–1236. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.4666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yasuda H, et al. Osteoclast differentiation factor is a ligand for osteoprotegerin/osteoclastogenesis-inhibitory factor and is identical to TRANCE/RANKL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3597–3602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kawai T, et al. B and T lymphocytes are the primary sources of RANKL in the bone resorptive lesion of periodontal disease. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:987–998. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simonet WS, et al. Osteoprotegerin: a novel secreted protein involved in the regulation of bone density. Cell. 1997;89:309–319. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80209-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Teng YT, et al. Gamma interferon positively modulates Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans-specific RANKL+ CD4+ Th-cell-mediated alveolar bone destruction in vivo. Infect Immun. 2005;73:3453–3461. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.6.3453-3461.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiao Y, et al. Induction of bone loss by pathobiont-mediated NOD1 signaling in the oral cavity. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;13:595–601. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takeuchi O, et al. Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell. 2010;140:805–820. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liang S, et al. The C5a receptor impairs IL-12-dependent clearance of Porphyromonas gingivalis and is required for induction of periodontal bone loss. J Immunol. 2011;186:869–877. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abe T, et al. Local complement-targeted intervention in periodontitis: proof-of-concept using a C5a receptor (CD88) antagonist. J Immunol. 2012;189:5442–5448. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Papadopoulos G, et al. Macrophage-specific TLR2 signaling mediates pathogen-induced TNF-dependent inflammatory oral bone loss. J Immunol. 2013;190:1148–1157. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aoyama N, et al. Toll-like receptor-2 plays a fundamental role in periodontal bacteria-accelerated abdominal aortic aneurysms. Circ J. 2013;77:1565–1573. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-12-1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Popadiak K, et al. Biphasic effect of gingipains from Porphyromonas gingivalis on the human complement system. J Immunol. 2007;178:7242–7250. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.7242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eskan MA, et al. The leukocyte integrin antagonist Del-1 inhibits IL-17-mediated inflammatory bone loss. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:465–473. doi: 10.1038/ni.2260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Masumoto J, et al. NOD1 acts as an intracellular receptor to stimulate chemokine production and neutrophil recruitment in vivo. J Exp Med. 2006;203:203–213. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hasegawa M, et al. Differential release and distribution of NOD1 and NOD2 immunostimulatory molecules among bacterial species and environments. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:29054–29063. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602638200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hajishengallis G, et al. Low-abundance biofilm species orchestrates inflammatory periodontal disease through the commensal microbiota and complement. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;10:497–506. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rovin S, et al. The influence of bacteria and irritation in the initiation of periodontal disease in germ-free and conventional rats. J Periodontal Res. 1966;1:193–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1966.tb01860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bryant CE, et al. The molecular basis of the host response to lipopolysaccharide. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:8–14. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jain S, et al. A novel class of lipoprotein lipase-sensitive molecules mediates Toll-like receptor 2 activation by Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect Immun. 2013;81:1277–1286. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01036-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Masoud H, et al. Investigation of the structure of lipid A from Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans strain Y4 and human clinical isolate PO 1021-7. Eur J Biochem. 1991;200:775–781. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lima HR, et al. The essential role of toll like receptor-4 in the control of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans infection in mice. J Clin Periodontol. 2010;37:248–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2009.01531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takeda K, et al. Recognition of lipopeptides by Toll-like receptors. J Endotoxin Res. 2002;8:459–463. doi: 10.1179/096805102125001073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fujimoto Y, et al. Peptidoglycan as NOD1 ligand; fragment structures in the environment, chemical synthesis, and their innate immunostimulation. Nat Prod Rep. 2012;29:568–579. doi: 10.1039/c2np00091a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hasegawa M, et al. Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 1 mediates recognition of Clostridium difficile and induces neutrophil recruitment and protection against the pathogen. J Immunol. 2011;186:4872–4880. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schleifer KH, et al. Peptidoglycan types of bacterial cell walls and their taxonomic implications. Bacteriol Rev. 1972;36:407–477. doi: 10.1128/br.36.4.407-477.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hasegawa M, et al. Transitions in oral and intestinal microflora composition and innate immune receptor-dependent stimulation during mouse development. Infect Immun. 2010;78:639–650. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01043-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Höltje JV. Growth of the stress-bearing and shape-maintaining murein sacculus of Escherichia coli. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:181–203. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.1.181-203.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nigro G, et al. Muramylpeptide shedding modulates cell sensing of Shigella flexneri. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:682–695. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pradipta AR, et al. Characterization of natural human nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain protein 1 (NOD1) ligands from bacterial culture supernatant for elucidation of immune modulators in the environment. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:23607–23613. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.137893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nair BC, et al. Biological effects of a purified lipopolysaccharide from Bacteroides gingivalis. J Periodontal Res. 1983;18:40–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1983.tb00333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lino Y, et al. The bone resorbing activities in tissue culture of lipopolysaccharides from the bacteria Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Bacteroides gingivalis and Capnocytophaga ochracea isolated from human mouths. Arch Oral Biol. 1984;29:59–63. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(84)90043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fujimoto Y, et al. Innate immunomodulation by lipophilic termini of lipopolysaccharide; synthesis of lipid As from Porphyromonas gingivalis and other bacteria and their immunomodulative responses. Mol Biosyst. 2013;9:987–996. doi: 10.1039/c3mb25477a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Burns E, et al. Cutting Edge: TLR2 is required for the innate response to Porphyromonas gingivalis: activation leads to bacterial persistence and TLR2 deficiency attenuates induced alveolar bone resorption. J Immunol. 2006;177:8296–82300. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.12.8296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Travassos LH, et al. Toll-like receptor 2-dependent bacterial sensing does not occur via peptidoglycan recognition. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:1000–1006. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chamaillard M, et al. An essential role for NOD1 in host recognition of bacterial peptidoglycan containing diaminopimelic acid. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:702–707. doi: 10.1038/ni945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rautemaa R, et al. Complement-resistance mechanisms of bacteria. Microbes Infect. 1999;1:785–794. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(99)80081-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Garlet GP, et al. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans-induced periodontal disease in mice: patterns of cytokine, chemokine, and chemokine receptor expression and leukocyte migration. Microbes Infect. 2005;7:738–747. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Diaz R, et al. Characterization of leukotoxin from a clinical strain of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Microb Pathog. 2006;40:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bostanci N, Belibasakis GN. Porphyromonas gingivalis: an invasive and evasive opportunistic oral pathogen. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2012;333:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2012.02579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]