Abstract

When compared to single mutants for Follistatin or Noggin, we find that double mutants display a dramatic further reduction in trunk cartilage formation, particularly in the vertebral bodies and proximal ribs. Consistent with these observations, expression of the early sclerotome markers Pax1 and Uncx is diminished in Noggin;Follistatin compound mutants. In contrast, Sim1 expression expands medially in double mutants. As the onset of Follistatin expression coincides with sclerotome specification, we argue that the effect of Follistatin occurs after sclerotome induction. We hypothesize that Follistatin aids in maintaining proper somite size, and consequently sclerotome progenitor numbers, by preventing paraxial mesoderm from adopting an intermediate/lateral plate mesodermal fate in the Noggin-deficient state.

Keywords: BMP antagonist, axial skeleton, sclerotome, mouse

Introduction

Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) antagonists supply a critical permissive signal in sclerotome specification (Stafford et al., 2011). Elevated BMP signaling resulting from Noggin mutation results in the loss of caudal vertebrae (Brunet et al., 1998), while concurrent ablation of the BMP antagonist genes Gremlin1 and Noggin result in a dramatic reduction in the expression of sclerotome-specific genes Pax1, Pax9, Uncx, and Nkx3.2, and a complete failure to form the axial skeleton. In contrast, embryos lacking Gremlin1 alone have normal sclerotomes (Khokha et al., 2003), raising the possibility that other BMP antagonists that lack an overt axial skeletal phenotype may function in sclerotome induction. Once such gene with especially striking expression in the early somites is Follisatin.

Follistatin encodes a cysteine-rich protein that inhibits the activity of Activins and BMPs (Amthor et al., 2002; Fainsod et al., 1997; Hemmati-Brivanlou et al., 1994; Iemura et al., 1998; Michel et al., 1993) by antagonizing both type 1 and type 2 receptor binding (Thompson et al., 2005). Follistatin binds and inactivates Myostatin/GDF8, thereby permitting Pax3 and MyoD-mediated myogenesis (Amthor et al., 2004). Consistent with a role in promoting the skeletal muscle lineage, mice lacking the Follistatin gene exhibit diminished muscle mass (Matzuk et al., 1995). In addition, these mutants exhibit defects in the whiskers, hard palate, and teeth, and die at birth due to respiratory distress (Matzuk et al., 1995). Follistatin null mice also fail to form the most posterior, floating 13th rib, suggesting involvement in the anterior-posterior regionalization of the axial skeleton. However, in contrast to the skeletal defect observed in Noggin mutants, Follistatin-deficient mice do not display regions of axial skeletal agenesis or hypertrophy. Follistatin is expressed in somites, the mesodermal units that flank the neural tube and from which both the axial skeleton and skeletal muscle derive. Nevertheless, no role in somite patterning has been attributed to Follistatin. Using conditional alleles for Noggin and Follistatin, we tested the hypothesis that Follistatin might overlap in function with Noggin and contribute to development of the axial skeleton.

Material and Methods

Conditional alleles for Noggin, Follistatin, and Gremlin1, and the beta-actin promoter driven cre line were previously described (Jorgez et al., 2004; Stafford et al., 2011; Gazzerro et al., 2007; Lewandoski et al., 1997). Alleles were maintained on a mice from a mixed C57/B6;129/Ola;FVB background. Whole mount in situ hybridization and Alcian Blue cartilage stains were performed as described (Khokha et al., 2003; Stafford et al., 2011). Quantitative PCR was performed on a BioRad CFX-100 Real Time System using the following primer sets (all annealing temperatures 60° C). Chordin: GAC TGC TGC AAA CAG TGT CCG TGT CC, ACT GAT GGG TGC CAG CTC T; Follistatin: CCT CCT GCT GCT GCT ACT CT, GGT GCT GCA AAC ACT CTT CCT; Gapdh: TTG ATG GCA ACA ATC TCC AC, CGT CCC GTA GAC AAA ATG GT; Gremlin1: ACA GCG AAG AAC CTG AGG AC, CCT TTC TTT TTC CCC TCA GC; Meox1: GAA GGC TGT CCT CTC CTT CC, CGG AGA AGA AAT CAT CCA GAA; Noggin: TGT ACG CGT GGA ATG ACC TA, GTG AGG TGC ACA GAC TTG GA; Pax1: GGC AGT CCG TGT AAG CTA CC, CAA TGA CCT TCA AAC ACC GA; Uncx: GGA GAA GGC GTT CAA TGA GA, CTT CTT TCT CCA TTT GGC CC.

Results

Follistatin is expressed in somites

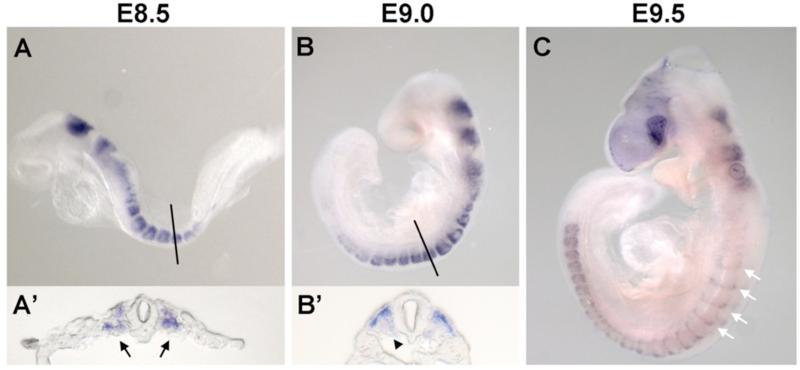

Initiating at E6.5, Follistatin is expressed dynamically in the primitive streak, central nervous system and paraxial mesoderm (Albano and Smith, 1994). We stained WT mouse embryos between E8.5 and E10.0 for Follistatin to define expression in the developing trunk. We confirmed that Follistatin is expressed in paraxial mesoderm, with expression initiating throughout the epithelial somite shortly after somitogenesis (Fig.1A). As the newly formed somite undergoes initial pattern formation, Follistatin expression becomes concentrated in the dorsal lateral aspect of the somite(Fig.1B). By the time the somite is 30 hours old, Follistatin expression is restricted to the posterior aspect of the dermomyotome (Fig.1C).

Fig. 1. Follistatin expression during somite pattern formation.

Whole mount in situ hybridizations for Follistatin, lateral views. (A) E8.5 Follistatin expression in the newly-formed somites and hindbrain. (A’) Magnified transverse view at the level of the line in panel A embryo showing Follistatin expression throughout the somite (arrows). (B) Follistatin expression becomes restricted to the dermomyotome. (B’) Magnified transverse view of dermomyotome expression of Follistatin at the level of the black in panel B embryo; note decreased signal in the sclerotome (arrowhead). (C) At E9.5, Follistatin expression is detectable in the posterior dermomyotome (white arrows).

We reasoned that the onset of Follistatin expression in the embryonic trunk is likely too late for Follistatin to function in initial somite patterning; the appearance of Follistatin transcript coincides with the onset of sclerotome and dermomyotome marker expression. In contrast, Noggin and Gremlin1, which together are required for sclerotome specification, are expressed well before somite formation. Nevertheless, the striking and dynamic expression of Follistatin during the specification of somite-derived tissues is consistent with a role in somite development. Although no somite abnormalities were described for embryos lacking Follistatin (Matzuk et al., 1995), the functional redundancy exhibited by other BMP antagonists (Anderson et al., 2002; Bachiller et al., 2000; Stafford et al., 2011) led us to posit that loss of Follistatin may exacerbate the somite defects associated with loss of Noggin, the antagonist with the most severe somite phenotype. To test the hypothesis that Follistatin and Noggin interact genetically in somite development, we generated Noggin;Follistatin compound mutants.

We crossed females homozygous for conditional alleles for Noggin (Stafford et al., 2011) and Follistatin (Jorgez et al., 2004) to males heterozygous for these alleles and also homozygous for a transgene expressing Cre from the beta-actin promoter (Lewandoski et al., 1997). This approach produces equal numbers of each of the following genetic classes: Nogfx/+;Fstfx/+ , used as controls; Nogfx/fx;Fstfx/+, Noggin mutants; Nogfx/+;Fstfx/fx , Follistatin mutants; Nogfx/fx;Fstfx/fx , double mutants. Quantitative PCR from genomic DNA confirmed that embryos bearing two conditional alleles retained less than 0.003% of inter-floxed DNA for Noggin and Follistatin, indicating successful, ubiquitous gene ablation. Moreover, as discussed below, homozygous mutant embryos displayed previously described Noggin and Follistatin null mutant phenotypes.

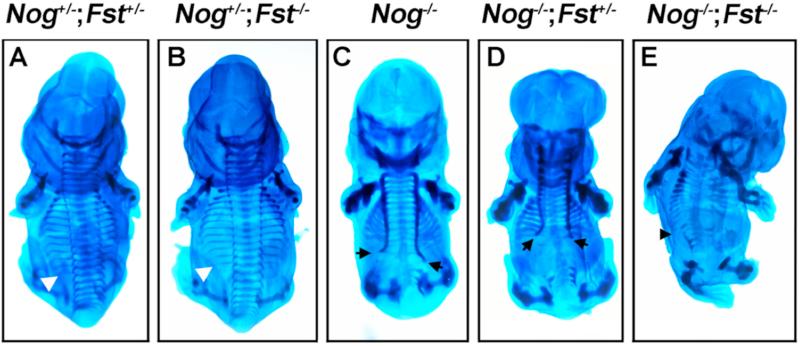

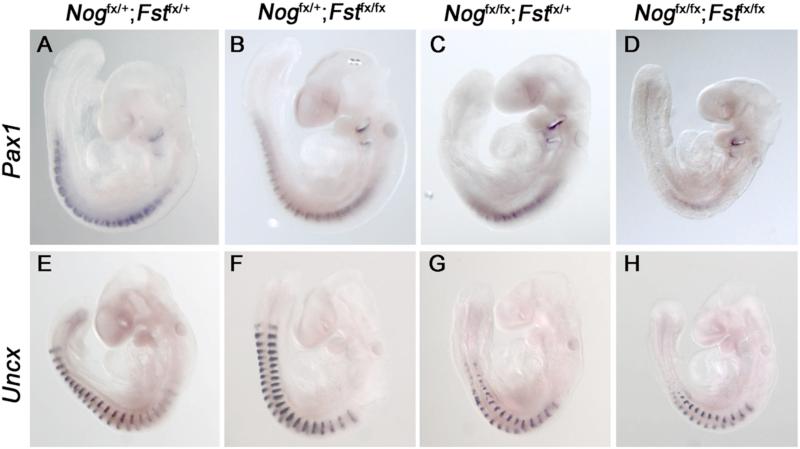

Follistatin interacts genetically with Noggin in axial skeleton development

As our primary interest lies in the role of BMP antagonist genes in axial skeleton development, we first compared the morphologies of ribs, vertebrae, and spinous processes in the different genetic classes by whole-mount alcian blue staining at E13.5 (Fig.2). Nogfx/+;Fstfx/+ skeletons exhibit normal axial skeleton morphology. While the skeletal elements of Nogfx/+;Fstfx/fx specimens were properly articulated and had normal length and diameter, in 4 of 5 skeletons the 13th rib was absent, consistent with the description of the Follistatin null animals (Fig. 2B; Matzuk et al., 1995). As we previously reported, embryos lacking only Noggin exhibited hyperplasia of the thoracic ribs and vertebrae, absent cartilage in the lumbar region, and a reappearance of vertebral bodies at the level of the pelvis (Fig. 2C; Stafford et al., 2011). Deletion of one or both copies of Follisatin dramatically increased the severity of the Noggin axial skeleton phenotype. The position of the most posterior axial skeletal element in Nogfx/fx;Fstfx/+ examples was further anterior than in Nogfx/fx examples (Fig 2, compare arrows.). Furthermore, the halves of vertebral bodies were misaligned in all 4 Nogfx/fx;Fstfx/+ specimens examined. Ablation of both copies of Follistatin enhanced the defects of the medial axial skeleton. The vertebral bodies in Nogfx/fx;Fstfx/fx were reduced (4 of 4; Fig 2E). In addition, the diameter of the proximal ribs was diminished in comparison to distal ribs. From our examination of these skeletons, we conclude that loss of Follistatin enhances the Noggin skeletal phenotype and that the midline aspects of the axial skeleton, including vertebral bodies and proximal ribs, are the more severely affected elements. Pax1 and Pax9 function together in the formation of the vertebral column (Peters et al., 1999) while Uncx is required for pedicles, transverse processes, and proximal ribs (Leitges et al., 2000). We hypothesized that if the loss of Follistatin in Noggin mutants enhances deficiencies in more medial aspects of the axial skeleton, the expression of genes required for these elements may be most affected. We therefore analyzed Pax1 and Uncx expression in Nogfx/+;Fstfx/+ (controls), Nogfx/+;Fstfx/fx , (Follistatin mutant-Noggin heterozygotes), Nogfx/fx;Fstfx/+, (Noggin mutant-Follistatin heterozygotes) and Nogfx/fx;Fstfx/fx (double mutants) at E9.5 by whole-mount in situ hybridization (WM-ISH; Fig. 3). Expression of both Pax1 and Uncx in Follistatin-deficient embryos was the same as in controls. However, as copies of Follistatin were removed from Noggin mutants, the posterior limit of Pax1 (n = 3) and Uncx (n = 3) expression became restricted to increasingly anterior positions. Nevertheless, while the signal was diminished, Noggin;Follistatin double mutant embryos still expressed Pax1 and Uncx. To measure subtle changes in somite marker activity, we performed quantitative RT-PCR (Sup. Fig. 1). This analysis confirmed that loss of Follistatin does marginally reduce Pax1 and Uncx compared to loss of Noggin alone. However, if Pax1 and Uncx expression is expressed as a percentage of a general paraxial mesoderm marker, in this case Meox1, the loss of Follistatin does not further reduce Pax1. Thus the diminished Pax1 and Uncx transcript levels are a result of a reduction in paraxial mesoderm.

Fig. 2. Follistatin enhances the Noggin mutant skeletal phenotype.

Whole mount E13.5 embryos stained with alcian blue to detect cartilage, dorsal views. Nogfx/+;Fstfx/+ (A) differ from Nogfx/+;Fstfx/fx (B) examples differ only in the absence of the 13th rib (arrowheads). (C) A Nogfx/fx mutant displaying thickened cervical and thoracic skeletal elements and reduced lumbar cartilage. (D) In Nogfx/fx;Fstfx/+ animals, formation of the cartilage of the axial skeleton arrests at a more anterior aspect of the embryo. (E) Deletion of both Follistatin and Noggin results in an almost complete loss of the medial aspects of the centrum, processes, and proximal ribs.

Fig. 3. Sclerotome marker expression is diminished in Noggin;Follistatin mutants.

E9.5 Whole mount in situ hybridizations for Pax1 (A-D) and Uncx (E-H), lateral views. Nogfx/+;Fstfx/+ (A, E) and Nogfx/+;Fstfx/fx (B, F) expressed Pax1 (A, B) and Uncx (E, F) normally. (C, G) Nogfx/fx;Fstfx/+ specimens exhibit reduced level of both transcripts in the presumptive lumbar region. In Nogfx/fx;Fstfx/fx animals, the posterior limit of expression was somite 10 for Pax1 (D) and somite 14 for Uncx (H).

Generally, the distal ribs in Follistatin;Noggin compound mutants were the least severely affected elements of the axial skeleton. Surprisingly, Nogfx/fx;Fstfx/fx double mutants sometimes exhibited condensations in the lateral lumbar region (3 of 5), some of which had the appearance of ribs. The origins of the distal ribs are controversial. One embryological study using chick and quail chimeras suggests that progenitors in the lateral dermomyotome give rise to the distal ribs (Kato and Aoyama, 1998). Consistent with this analysis, genetic ablation of the Myf5 lineage results in severe distal rib defects, although this may result from transient Myf5 expression in pre-somitic mesoderm or be a non-cell autonomous effect resulting from the absence of an inductive interaction supplied by lateral dermomyotome (Haldar et al., 2008). A second avian chimera study using smaller grafts concluded that distal ribs are indeed a derivative of the sclerotome (Huang et al., 2000). While imperfectly understood, it is clear that lateral domains of the somite are critical for normal axial skeleton formation. We therefore analyzed Myf5 expression in Noggin;Follistatin compound mutants. We observed no changes in Myf5 expression in E10.5 Noggin-mutants upon removal of one of both copies of Follistatin, consistent with our observation that the medial derivatives are the most severely affected features of Nogfx/fx;Fstfx/fx double mutant skeletons (Sup. Fig. 2).

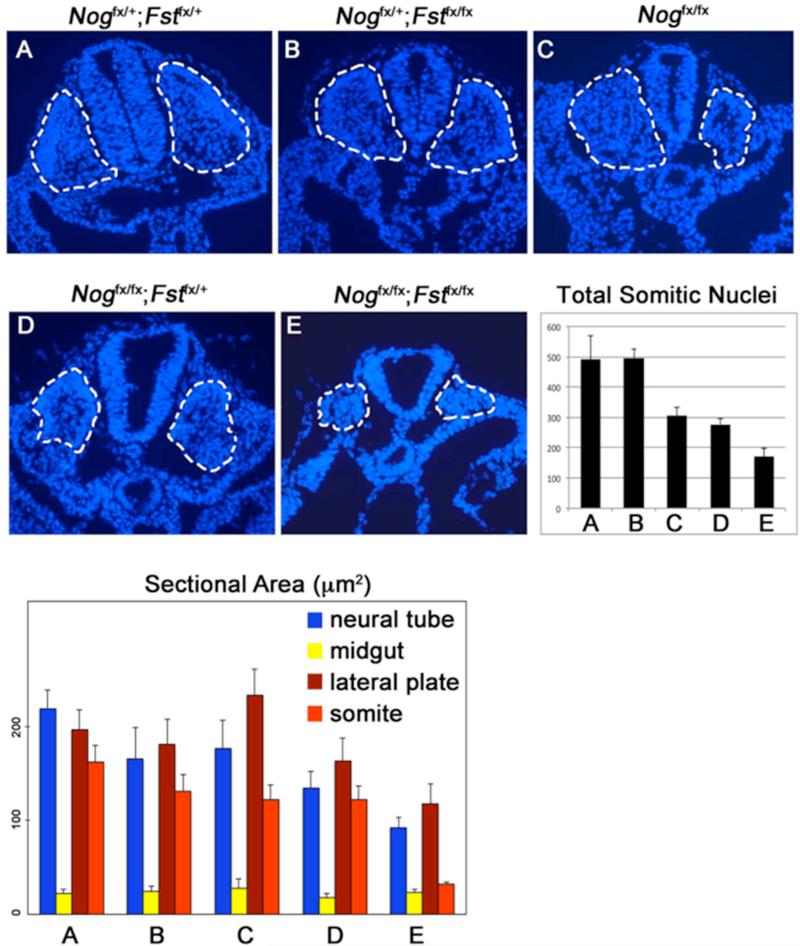

Noggin;Follistatin somites are smaller and lateralized

The diminished levels of sclerotome gene expression, particularly in domains destined to contribute to more medial elements of the axial skeletal, could be caused by elevated cell death or reduced proliferation in these lineages. To define the contribution of these processes, we performed TUNEL and phosphorylated histone-3 (PH3) on sections cut from the anterior-posterior level of somite 12-16 in E9.5 embryos of each genetic class. Trunk segments from at least 3 separate embryos from each genetic class were analyzed. Essentially no TUNEL positive cells were detected in paraxial mesoderm; most sections had none (not shown). We did observe previously described dorsal neural tube signal in embryos of all classes lacking Noggin (McMahon et al., 1998; Stafford et al., 2011), demonstrating efficacy of the assay. To define proliferation rates in the paraxial mesoderm between the different classes, we counted PH3+ nuclei and expressed these as a function of total nuclei. We restricted our counts to the morphologically defined somite. After analyzing a minimum of 11 sections from at least 3 embryos of each genotype, we found that the overall mitosis rates were not statistically different; about 3% of cells are mitotic regardless of genetic class (not shown). A caveat to our approach is that we had no way of counting sclerotome exclusively in our sections. However, we could find no indication of a difference in proliferation rate between genotypes at the stages we examined.

The most striking difference between the somites of the different genotypes was the overall quantity of paraxial mesoderm; in comparison to controls and Follistatin mutants (Fig.4A,B), Noggin and Noggin mutant-Follistatin heterozygotes exhibited significantly smaller thoracic trunk somites (Fig.4C,D). The somites of embryos lacking both genes were smaller still (Fig.4E). A complication of these analyses was the relative smaller size of antagonist-mutant embryos. To account for the size differences in between embryos of different genotypes, we compared the area of the neural tube, somite, midgut and somatic lateral plate in E9.5 sections collected just posterior to the forelimb. We found the total area of embryonic tissue in sections cut from specimens lacking Noggin and Follistatin was less than half that of controls, and exhibited a reduction in all tissues examined except for midgut. However, in double mutants, the somite was affected most; somite area was only 15% of the embryo, compared to 34% and 27% for controls and Noggin mutants, respectively. In contrast, the lateral plate mesoderm represented a proportionally greater amount of Noggin;Follistatin double mutant embryos, comprising 57% of the embryo, in contrast to 41% in controls. While the effect of Noggin ablation on somite size has been described (McMahon et al., 1998; Stafford et al., 2011), we were surprised that deletion of Follistatin enhanced this phenotype, as Follistatin expression initiates after somite formation. The overall diminished size of trunk structures in Noggin;Follistatin double mutant embryos may also be a consequence of diminished Follistatin expression in extraembryonic tissues. Follistatin expression has been reported in E7.5 parietal endoderm (Albano and Smith, 1994). We examined the expression of four BMP antagonist genes, Noggin, Follistatin, Gremlin1, and Chordin, in the E9.5 ectoplacental cone (Sup. Fig. 3). Follistatin expression was four-fold higher than the next highest expressed gene, Noggin, consistent with a role in placental function. Nevertheless, the proportionally larger lateral mesoderm and smaller paraxial mesoderm indicates a patterning defect. The absence of any overt proliferation differences raised the possibility that even after somites form, cells may continue to be influenced in their allocation to non-segmented lateral populations.

Fig. 4. Loss of Noggin and Follistatin results in smaller somites.

(A-E) 12 μm sections were collected from the E9.5 trunk posterior to the forelimb and stained with hoechst. These were delineated with the dashed line and counted. (Total Somitic Nuclei) Histogram summarizing somite size for the different genetic classes. Somites in Nogfx/+;Fstfx/+ and Nogfx/+;Fstfx/fx embryos (A, B) have significantly more cells than Nogfx/fx and Nogfx/fx;Fstfx/+ examples (C, D; P < 0.0001). These in turn have significantly more cells than Nogfx/fx;Fstfx/fx animals (E; < 0.0001). (Sectional Area) Histogram summarizing comparison of the area of different embryonic structures in transverse sections of the trunk. Regions were scored by morphology, bars in both graphs indicate 2× standard error, and a minimum of 5 sections cut from at least 3 embryos of each class were quantified.

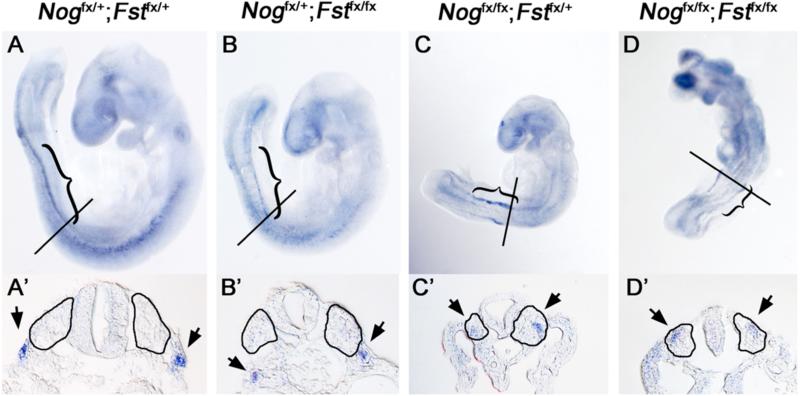

To access the lateral identity of paraxial mesoderm in Noggin;Follistatin compound mutants, we examined expression of the transcriptional repressor Sim1. Sim1 is expressed in the intermediate mesoderm of the posterior trunk and has been shown to expand medially when BMP signaling is elevated by removing Noggin (Wijgerde et al., 2005). We observedbilateral Sim1 expression posterior to the forelimb in all classes. In controls and Follistatin-deficient embryos, this expression was restricted to characteristic discrete stripes representing the intermediate mesoderm lateral to the morphologically distinct somites (Fig. 5A-B). As was observed in Wijgerde, et al., embryos lacking Noggin displayed a medial expansion of Sim1 into the lateral somite (4 of 4; Fig. 5C). This lateralization was further enhanced in Noggin;Follistatin double mutants, with expression extending in some cases to the neural tube (2 of 3; Fig. 5D). Ectopic Sim1 expression in the paraxial mesoderm is consistent with a model in which the loss of BMP antagonists results in a smaller population of progenitors competent to form axial skeleton.

Fig. 5. Sim1 expands medially in Noggin;Follistatin double mutants.

E9.5 Whole mount in situ hybridizations for Sim1, lateral views (A-D) and transverse sections at the level of the line. (A’-D’). (A, B) In Nogfx/+;Fstfx/+ and Nogfx/+;Fstfx/fx embryos, Sim1 is expressed in the thoracic somites and the intermediate mesoderm (brackets). (A’, B’) shows the position of the signal lateral to the somite (arrowheads). (C) Nogfx/fx;Fstfx/+ specimens exhibit a broader Sim1 expression domain that extends medially into the paraxial mesoderm (C’). Nogfx/fx;Fstfx/fx animals (D, D’) exhibit further medial expansion of Sim1 expression.

Taken together, our analysis of axial cartilage, somitic marker expression, and paraxial mesoderm size led us to hypothesize that the early sclerotome in Noggin mutants remains competent to be lateralized, and Follistatin functions to prevent this from occurring. These results suggest that medial-lateral mesoderm patterning continues over time and that even after somites form and assume their initial gene expression patterns they can take on the identity of more lateral mesodermal cell types.

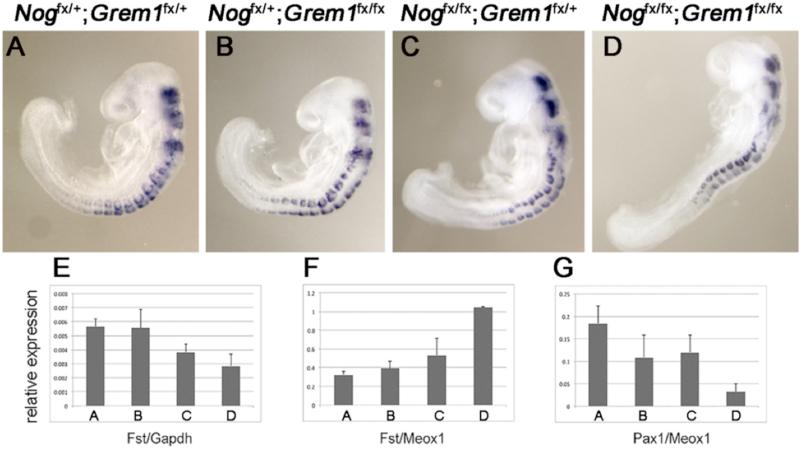

BMP does not inhibit Follistatin activation

Our original interest in Follistatin stemmed from our previously unpublished observation that Follistatin transcript levels are reduced in Noggin;Gremlin1 compound mutant trunks at E9.0, suggesting that activation of Follistatin may require inhibition of BMP signaling. However, when we compared Follistatin expression in Noggin;Gremlin1 double mutants to other genetic classes at E9.0, there was no apparent qualitative difference in signal (Fig.6A-D). Quantitative RT-PCR did reveal a 50% reduction of Follistatin transcript levels in Noggin;Gremlin1 double mutants when compared to Gapdh (Fig.6E). However, this was not observed when Follistatin transcript levels were normalized to those of Meox1, a general marker of paraxial mesoderm(Fig.6F). In contrast, Pax1, which is expressed minimally in embryos lacking Noggin and Gremlin (Stafford et al., 2011), is reduced relative to Meox1(Fig.6G). We interpret the diminished Follistatin in Noggin;Gremlin1 compound mutants as a consequence of an overall reduction in somitic size (McMahon et al., 1998). These data suggest that the elevated BMP does not interfere with Follistatin activation. Indeed, BMP may promote Follistatin expression in the somite.

Fig. 6. Somitic Follistatin is elevated in Noggin;Gremlin1 double mutants.

E9.5 Whole mount in situ hybridizations for Fst, lateral views (A-D). (A) Nogfx/+;Grem1fx/+ controls, (B) Nogfx/+;Grem1fx/fx Gremlin1 mutants, (C) Nogfx/fx;Grem1fx/+ Noggin mutants, and (D) Nogfx/fx;Grem1fx/fx Noggin;Gremlin1 double mutants all express Follistatin. (E-G) Histograms reporting quantitative PCRs. (E) Relative to expression of Gapdh, Follistatin is modestly reduced in Noggin and Noggin;Gremlin1 double mutants. (F) When expressed as a function of transcript levels of Meox1, a general marker of the somite, Follistatin is elevated. (G) In contrast, Pax1, a gene that requires Noggin and Gremlin1 for expression, is diminished. Bars indicate 2× standard error.

Discussion

Of the different BMP antagonists, loss of Noggin has the most severe effect on the patterning of the axial skeleton. Nevertheless, recent analysis of compound Noggin and Gremlin mutants has reveled the contributions of other BMP antagonist genes. Here we present evidence that Follistatin functions to maintain paraxial mesoderm identity during early somite-patterning events. Coincident with the activation of Follistatin in the regionalizing somite, the expression of Noggin and Gremlin1 diminishes. Thus, there is a “BMP antagonist relay” in early sclerotome development.

In the chick, application of Noggin to the presumptive lateral plate mesoderm results in ectopic somites (Tonegawa and Takahashi, 1998). Similarly, loss of an allele of BMP4 ameliorates the lateralization of the paraxial mesoderm observed in Noggin mutant embryos (Wijgerde et al., 2005). We show that the additional loss of Follistatin causes Noggin-deficient somitic tissue to more extensively adopt intermediate/lateral late mesoderm identity, which is consistent with a persistent function for BMP/BMP antagonist signaling during the differentiation of somite derivatives. Moreover, our analysis provides a surprising insight into the duration during which medial-lateral identity can be specified. Our data here suggest that even after a somite is formed, elevated BMP can reassign paraxial mesoderm to a lateral, non-segmented fate.

In all antagonist-deficient embryos, the severity of the paraxial mesoderm phenotype increases posteriorly. A likely explanation is that BMPs secreted from lateral mesoderm and extra-embryonic sources are concentrated in the posterior (McMahon et al., 1998), and therefore the repercussions of decreased antagonist activity are more severe. In addition, we propose that morphology of the developing embryo contributes to this phenomenon; the lumbar region of the embryo is thinner than the thoracic region, and laterally-derived BMPs have less distance to diffuse to reach sensitive somitic precursors. Consistent with this interpretation, in mouse strains that exhibit a more mild Noggin phenotype, somite markers are expressed in the pelvic region (Stafford et al., 2011). Our work adds to existing data that indicates that in embryos with elevated BMP signaling, somites are smaller and lost posteriorly because cells are aberrantly specified as IM/LPM.

Follistatin expression in the somites is conserved in the vertebrates. In addition to those of amniotes, Follistatin homologues are expressed in the somites of salmon, zebrafish, and lamprey (Bauer et al., 1998; Hammond et al., 2009; Macqueen and Johnston, 2008). Axial skeleton formation in teleosts varies across species, and may not exist at all in agnathans (Ogasawara et al., 2000), although irregular axial cartilaginous condensations that may reflect primitive skeletal elements have been described. This argues against an ancestral role for somitic Follistatin in sclerotome formation. Also, either notochord or Shh interferes with somitic Follistatin expression, which is the opposite activity predicted for sclerotome-promoting genes (Amthor et al., 1996). This activity may not be direct, and might best be interpreted as a Hh-mediated inhibition of the myogenic lineage; high levels of Shh blocks Wnt-mediated dermomyotome induction (Marcelle et al., 1997). Nevertheless, our data clearly demonstrate that the axial skeleton is more severely affected in Noggin;Follistatin embryos vs. embryos lacking Noggin alone. We propose that across vertebrates, Follistatin normally functions to control TGF-beta-mediated proliferation and differentiation of the muscle progenitors of the dermomyotome (Amthor et al., 2004; Manceau et al., 2008). In the Noggin-mutant state, Follistatin can resist lateralization of paraxial mesoderm by BMP, thus explaining the increased severity of axial skeletal deficiencies observed in Noggin;Follistatin double mutants.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Loss of Follistatin enhances Noggin mutant axial skeleton defects

In Noggin mutants, Follistatin aids in maintaining proper somite size

Follistatin affects somite size following somite formation

Follistatin limits BMP-mediated lateralization of paraxial mesoderm

Noggin and Gremlin1 mutation does not reduce somitic Follistatin activation

Acknowledgements

We thank Debbie Pangilinan for animal care. This work is supported by NIH GM49346.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Albano RM, Smith JC. Follistatin expression in ES and F9 cells and in preimplantation mouse embryos. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 1994;38:543–547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amthor H, Connolly D, Patel K, Brand-Saberi B, Wilkinson DG, Cooke J, Christ B. The expression and regulation of follistatin and a follistatin-like gene during avian somite compartmentalization and myogenesis. Dev. Biol. 1996;178:343–362. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amthor H, Nicholas G, McKinnell I, Kemp CF, Sharma M, Kambadur R, Patel K. Follistatin complexes Myostatin and antagonises Myostatin-mediated inhibition of myogenesis. Dev. Biol. 2004;270:19–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer H, Meier A, Hild M, Stachel S, Economides A, Hazelett D, Harland RM, Hammerschmidt M. Follistatin and noggin are excluded from the zebrafish organizer. Dev. Biol. 1998;204:488–507. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunet LJ, McMahon JA, McMahon AP, Harland RM. Noggin, cartilage morphogenesis, and joint formation in the mammalian skeleton. Science. 1998;280:1455–1457. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5368.1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzerro E, Smerdel-Ramoya A, Zanotti S, Stadmeyer L, Durant D, Economides AN, Canalis E. Conditional deletion of gremlin causes a transient increase in bone formation and bone mass. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:31549–31557. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701317200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond KL, Baxendale S, McCauley DW, Ingham PW, Whitfield TT. Expression of patched, prdm1 and engrailed in the lamprey somite reveals conserved responses to Hedgehog signaling. Evol. Dev. 2009;11:27–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2008.00300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang R, Zhi Q, Schmidt C, Wilting J, Brand-Saberi B, Christ B. Sclerotomal origin of the ribs. Development. 2000;127:527–532. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.3.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgez CJ, Klysik M, Jamin SP, Behringer RR, Matzuk MM. Granulosa cell-specific inactivation of follistatin causes female fertility defects. Mol. Endocrinol. 2004;18:953–967. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khokha MK, Hsu D, Brunet LJ, Dionne MS, Harland RM. Gremlin is the BMP antagonist required for maintenance of Shh and Fgf signals during limb patterning. Nat. Genet. 2003;34:303–307. doi: 10.1038/ng1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewandoski M, Meyers EN, Martin GR. Analysis of Fgf8 gene function in vertebrate development. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 1997;62:159–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macqueen DJ, Johnston IA. Evolution of follistatin in teleosts revealed through phylogenetic, genomic and expression analyses. Dev. Genes Evol. 2008;218:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s00427-007-0194-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manceau M, Gros J, Savage K, Thomé V, McPherron A, Paterson B, Marcelle C. Myostatin promotes the terminal differentiation of embryonic muscle progenitors. Genes Dev. 2008;22:668–681. doi: 10.1101/gad.454408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcelle C, Stark MR, Bronner-Fraser M. Coordinate actions of BMPs, Wnts, Shh and noggin mediate patterning of the dorsal somite. Development. 1997;124:3955–3963. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.20.3955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon JA, Takada S, Zimmerman LB, Fan CM, Harland RM, McMahon AP. Noggin-mediated antagonism of BMP signaling is required for growth and patterning of the neural tube and somite. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1438–1452. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.10.1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogasawara M, Shigetani Y, Hirano S, Satoh N, Kuratani S. Pax1/Pax9-Related genes in an agnathan vertebrate, Lampetra japonica: expression pattern of LjPax9 implies sequential evolutionary events toward the gnathostome body plan. Dev. Biol. 2000;223:399–410. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafford DA, Brunet LJ, Khokha MK, Economides AN, Harland RM. Cooperative activity of noggin and gremlin 1 in axial skeleton development. Development. 2011;138:1005–1014. doi: 10.1242/dev.051938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonegawa A, Takahashi Y. Somitogenesis controlled by Noggin. Dev. Biol. 1998;202:172–182. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.8895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijgerde M, Karp S, McMahon J, McMahon AP. Noggin antagonism of BMP4 signaling controls development of the axial skeleton in the mouse. Dev. Biol. 2005;286:149–157. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.