Abstract

Background & Aims

Biliary epithelial cells (BECs) are considered to be a source of regenerating hepatocytes when hepatocyte proliferation is compromised. However, there is still controversy about the extent to which BECs can contribute to the regenerating hepatocyte population, and thereby to liver recovery. To investigate this issue, we established a zebrafish model of liver regeneration in which the extent of hepatocyte ablation can be controlled.

Methods

Hepatocytes were depleted by administration of metronidazole to Tg(fabp10a:CFP-NTR) animals. We traced the origin of regenerating hepatocytes using short-term lineage tracing experiments as well as the inducible Cre/loxP system; specifically, we utilized both a BEC tracer lineTg(Tp1:CreERT2) and a hepatocyte tracer line Tg(fabp10a:CreERT2). We also examined BEC and hepatocyte proliferation as well as liver marker gene expression during liver regeneration.

Results

BECs gave rise to most of the regenerating hepatocytes in larval and adult zebrafish after severe hepatocyte depletion. Following hepatocyte loss, BECs proliferated as they dedifferentiated into hepatoblast-like cells; they subsequently differentiated into highly proliferative hepatocytes that restored the liver mass. This process was impaired in zebrafish wnt2bb mutants; in these animals, hepatocytes regenerated but their proliferation was greatly reduced.

Conclusions

BECs contribute to regenerating hepatocytes following substantial hepatocyte depletion in zebrafish, thereby leading to recovery from severe liver damage.

Keywords: oval cells, liver regeneration, dedifferentiation, stem cells

Introduction

In the liver, there are two endodermal cell types: the hepatocytes, the main functional cells of the liver, and the biliary epithelial cells (BECs), also known as cholangiocytes, which form the biliary ducts that transport bile from the hepatocytes towards the gallbladder. During liver regeneration, hepatocytes proliferate to replenish lost hepatocytes. However, if hepatocyte proliferation is compromised, a subset of BECs actively proliferate to produce oval cells that later differentiate into hepatocytes1, 2.

Oval cells appear to originate from BECs in bile ductules and ductule extensions, the canals of Hering1, 2. Oval cells express both albumin and cytokeratin 19, which are hepatocyte and BEC markers, respectively, and can differentiate into hepatocytes or BECs when isolated and cultured in vitro3-5. Pulse-labeling with tritiated thymidine in rats6 and marker analyses in rats7 and humans8 support the conversion of oval cells to hepatocytes in the diseased liver, implying that BECs have the potential to give rise to hepatocytes to restore liver function. Recently, this potential has been rigorously tested in vivo, using the Cre/loxP lineage-tracing technique in mice, to determine whether BECs/oval cells indeed give rise to hepatocytes, and if so, to what extent they contribute to the pool of regenerated hepatocytes. Using the Sox9:CreERT2 line to label BECs, it was reported that Sox9-expressing BECs contributed extensively to hepatocytes during liver regeneration and homeostasis9. In contrast, subsequent studies reported that BECs minimally contributed to hepatocytes10-12. Labeling of all hepatocytes before diverse liver injuries led to the finding that nearly all regenerated hepatocytes were derived from preexisting hepatocytes11. Labeling of Sox9-expressing ductal plate cells, which later give rise to BECs and oval cells, at embryonic day 15.510 or osteopontin-expressing BECs at postnatal day 2012 revealed that BECs contributed minimally to hepatocytes during liver regeneration. Thus, whether BECs can extensively contribute to hepatocytes and thereby lead to liver recovery remains controversial.

We hypothesized that the severity of liver damage influences the extent of BEC-driven liver regeneration, and that severe liver damage will lead to an increased contribution of BECs to hepatocytes. To this end, we established a novel zebrafish liver regeneration model in which the extent of hepatocyte ablation can be controlled. Using this model, we found that upon severe hepatocyte ablation, BECs extensively contributed to hepatocytes, leading to full liver recovery from the damage. Moreover, BECs did not contribute to hepatocytes upon moderate hepatocyte ablation, indicating that the extent of liver damage determines the cell type used in the regenerative response.

Materials and Methods

Zebrafish Studies

Experiments were performed with approval of University Animal Care and Use Committees. Hepatocyte ablation of Tg(fabp10a:CFP-NTR) animals was performed by treating larvae with 10mM metronidazole (Mtz) in egg water supplemented with 0.2% DMSO and 0.2mM 1-phenyl-2-thiourea or adults with 5mM Mtz in system water supplemented with 0.5% DMSO. For Cre/loxP-mediated lineage tracing, Tg(fabp10a:CFP-NTR);Tg(ubi:loxP-GFP-loxP-mCherry);Tg(Tp1:CreERT2) or Tg(fabp10a:CFP-NTR);Tg(ubi:loxP-GFP-loxP-mCherry);Tg(fabp10a:CreERT2) embryos were treated with 10 M 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT) at 48 hours post-fertilization (hpf) for 36 hours to induce Cre-mediated recombination, and then with Mtz for hepatocyte ablation. 1-30 days later, animals were harvested and processed for immunostaining to reveal the lineage-traced mCherry+ cells as previously described13. Other transgenic and mutant fish lines and analytic methods are described in the Supplementary material section.

Results

A zebrafish liver regeneration model allows for extreme hepatocyte ablation and rapid liver regeneration

We generated a transgenic line, Tg(fabp10a:CFP-NTR)s931, that expresses bacterial nitroreductase (NTR), fused with cyan fluorescent protein (CFP), under the hepatocyte-specific fabp10a promoter. NTR converts the non-toxic prodrug, Mtz, into a cytotoxic drug, thereby ablating only NTR-expressing cells14-16. TUNEL labeling or active Caspase-3 immunostaining revealed apoptotic hepatocytes in Tg(fabp10a:CFP-NTR) larvae treated with Mtz for 18 or 36 hours, but not in controls (Supplementary Figure 1A-1B), indicating hepatocyte-specific ablation. To severely ablate hepatocytes and monitor subsequent liver regeneration, we treated Tg(fabp10a:CFP-NTR) larvae with Mtz from 3.5 to 5 days post-fertilization (dpf) for 36 hours (ablation, A36h) followed by Mtz washout, which we considered as the beginning of liver regeneration (R) (Figure 1A). After the ablation, at A36h, liver size was dramatically reduced compared to controls and very faint CFP expression was detected in the remaining liver (Figure 1B, arrows). However, strong CFP expression reappeared at 30 hours post-washout (A36h-R30h) and liver size appeared to fully recover by A36h-R102h (Figure 1C and Supplementary Figure 2B), indicating rapid liver regeneration after severe hepatocyte ablation in this model.

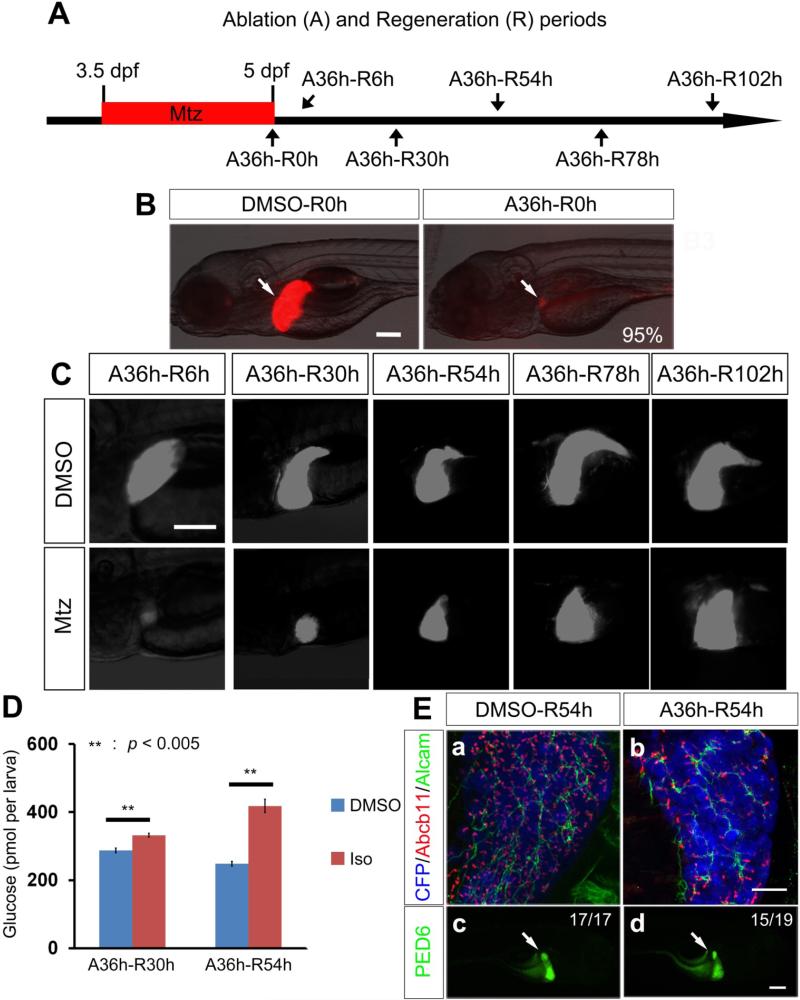

Figure 1.

A zebrafish liver regeneration model. (A) Scheme illustrating the periods of Mtz treatment (A, ablation) and liver regeneration (R). (B, C) To reveal liver size, CFP expression from Tg(fabp10a:CFP-NTR) larvae (B, red; C, white) was examined right after hepatocyte ablation (B) and during liver regeneration (C) under an epifluorescence microscope. (D) Glucose levels in the regenerating larvae treated with DMSO or isoprenaline (Iso) for 30 hours after hepatocyte ablation. (E) Confocal images showing whole-mount immunostaining of the regenerating liver reveal the correct location of bile canaliculi between hepatocytes and BECs, as assessed by Abcb11 (red) and Alcam (green) expression (Ea-Eb). Epifluorescence images of regenerating larvae treated with PED6 reveal the accumulation of the processed PED6 in the gallbladder at A36h-R54h (Ed, arrow), as in DMSO controls. Scale bars, 100 μm (B-C, Ec-Ed); 20 μm (Ea-Eb).

To determine whether liver function recovered during liver regeneration, we first examined the expression patterns of Abcb11, a bile salt export pump, present in the bile canaliculi of hepatocytes17, and Alcam which is present in the membrane of BECs18. Abcb11 expression in the liver was completely absent at A36h (Supplementary Figure 2A), but reappeared at the apical side of hepatocytes at A36h-R54h (Figure 1Eb). Second, we tested, using the fluorescently labeled fatty acid reporter PED6 which accumulates in the gallbladder after biliary secretion19, whether hepatocyte secretion into bile ducts occurred in the regenerating liver. PED6 accumulation in the gallbladder was detected in most regenerating larvae (15 out of 19) at A36h-R54h (Figure 1Ed, arrow). Third, we examined the expression of two hepatocyte-specific genes, ceruloplasmin (cp) and group-specific component (gc). cp is a multi-copper oxidase gene implicated in iron metabolism20; gc appears to be the only albumin gene family member present in the zebrafish genome21. cp or gc expression was not detected in the regenerating liver at A36h-R6h, but strongly present at A36h-R54h (Supplementary Figure 2C-2D). A recent report showed that treatment with isoprenaline, a β-adrenergic agonist, greatly increased expression of pck1, which encodes an enzyme catalyzing an early step in gluconeogenesis, resulting in an approximately 1.7-fold increase in glucose levels in 6 dpf larvae22. We observed a 1.15- and 1.68-fold increase in glucose levels at A36h-R30h and A36h-R54h, respectively (Figure 1D), indicating that the regenerating liver is responsive to isoprenaline-stimulated gluconeogenesis, further suggesting the recovery of functional hepatocytes. Altogether, these data indicate that liver function rapidly recovers after extreme hepatocyte loss.

The intrahepatic biliary network is disrupted after severe hepatocyte ablation but is rapidly reestablished during liver regeneration

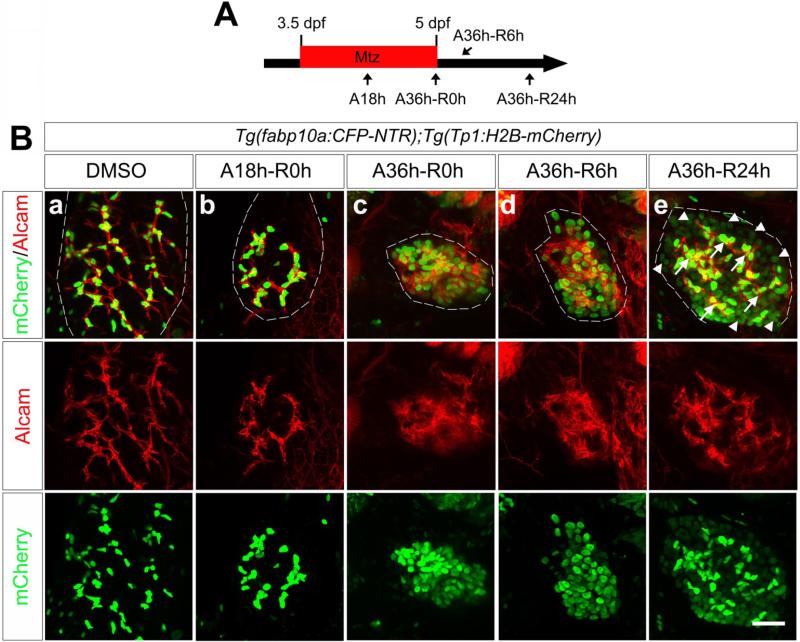

Since both hepatocytes and BECs are derived from hepatoblasts during development23, and a subset of BECs have the potential to give rise to hepatocytes in vitro3-5, we examined in detail how the intrahepatic biliary network composed of BECs changed during hepatocyte ablation and liver regeneration. To clearly reveal the network, we used Alcam antibodies and the Tg(Tp1:H2B-mCherry)s939 line that expresses a nuclear red fluorescent protein under the control of an element containing 12 RBP-Jĸ binding sites24. This element drives gene expression exclusively in BECs in the liver25, 26, allowing for easy detection of BEC nuclei (Figure 2B). As hepatocyte ablation proceeded, BECs appeared closer to each other (Figure 2Bb) and eventually aggregated at A36h-R0h, resulting in a collapsed intrahepatic biliary network (Figure 2Bc). However, this network was rapidly re-established during subsequent liver regeneration (Figures 2Be and 1Eb). Intriguingly, H2B-mCherry was strongly expressed in the re-established Alcam+ BECs, whereas it was weakly expressed in many Alcam− cells (Figure 2Be, arrows versus arrowheads). Weak H2B-mCherry+ cells were fabp10a:CFP-NTR+, whereas strong H2B-mCherry+ cells were fabp10a:CFP-NTR− (Supplementary Figure 3, arrowheads versus arrows), indicating that weak H2B-mCherry+ cells are hepatocytes. Since the extended stability of H2B-mCherry allows one to trace cell lineages over several cell divisions24, this expression pattern may suggest the generation of new hepatocytes from BECs upon severe hepatocyte ablation.

Figure 2.

The intrahepatic biliary network collapses upon severe hepatocyte ablation but is reestablished during liver regeneration. (A) Scheme illustrating the periods of Mtz treatment and liver regeneration. (B) Confocal images of the ablated or regenerating liver immunostained for mCherry (green) and Alcam (red). H2B-mCherry and Alcam are expressed in the nuclei and membrane of BECs, respectively. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Proliferation of BECs and hepatocytes during hepatocyte ablation and liver regeneration

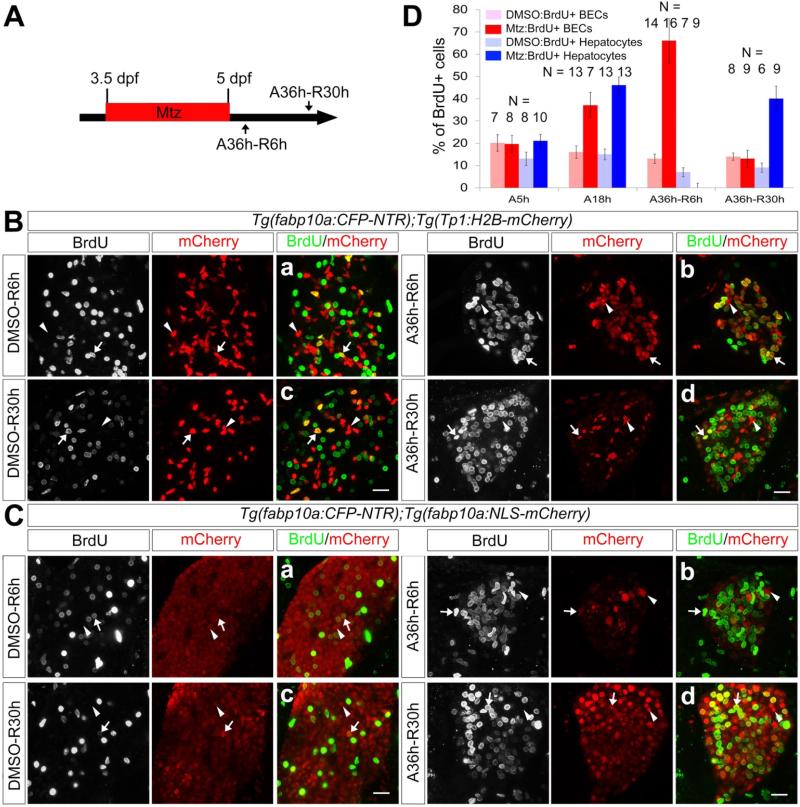

Since liver size rapidly recovered after hepatocyte ablation (Figure 1C), we investigated the extent to which the proliferation of BECs and hepatocytes contributed to liver regeneration. The Tg(Tp1:H2B-mCherry) and Tg(fabp10a:NLS-mCherry) lines were used to count BECs and hepatocytes, respectively. At A36h-R6h, most BECs were BrdU+ (Figure 3Bb, arrows; 66%±10) and few BrdU+ hepatocytes were detected (Figure 3Cb, arrows). However, at A36h-R30h, the BEC proliferation rate in the regenerating liver had decreased to the rate observed in controls (Figure 3Bd, 13%±4; Figure 3Bc, 14%±2), whereas hepatocyte proliferation had greatly increased in the regenerating liver compared to controls (Figure 3Cd, 40%±6; Figure 3Cc, 9%±2). These data suggest that BEC proliferation is temporarily enhanced after hepatocyte ablation and that subsequently, newly generated hepatocytes rapidly proliferate to restore liver mass.

Figure 3.

Proliferation of BECs and hepatocytes during liver regeneration. (A) Scheme illustrating the periods of Mtz treatment and liver regeneration. (B, C) Confocal images of the regenerating liver immunostained for BrdU. Tg(Tp1:H2B-mCherry) and Tg(fabp10a:NLS-mCherry) larvae were used to mark BEC (B) and hepatocyte (C) nuclei, respectively. The larvae were treated with BrdU for 6 hours prior to harvest. Arrows point to BrdU+;mCherry+ cells; arrowheads point to BrdU−;mCherry+ cells. Scale bars, 20 μm. (D) Graph showing the percentage of BrdU+ cells among BECs (red) or hepatocytes (blue) during liver regeneration. Error bars, ±SD.

We next investigated whether BEC or hepatocyte proliferation increased during hepatocyte ablation (A5h and A18h) as well as post-ablation (A36h-R6h and A36h-R30h). Mtz-treated larvae were harvested at A5h when liver size was not noticeably reduced and at A18h when it was noticeably reduced (data not shown). To quantify hepatocyte ablation levels, we counted the number of active Caspase-3+ and fabp10a:NLS-mCherry+ cells and found that 0%, 19±2%, and 78±8% of the hepatocytes at A5h, A18h, and A36h, respectively, were Caspase-3+ (Supplementary Figure 1C). Hepatocyte, but not BEC, proliferation in the ablating liver at A5h slightly but significantly increased compared to that in controls (21%±3 versus 13%±3; Figure 3D and Supplementary Figure 4B-4C). Moreover, both hepatocyte and BEC proliferation greatly increased in the ablating liver at A18h compared to controls (hepatocytes, 46%±4 versus 15%±2; BECs, 37%±6 versus 16%±3; Figure 3D and Supplementary Figure 4B-4C). These data indicate that hepatocyte and BEC proliferation increased during hepatocyte ablation as well as post-ablation. Altogether, these proliferation data reveal that moderate hepatocyte ablation (A5h) enhanced only hepatocyte proliferation, whereas intermediate ablation (A18h) enhanced both hepatocyte and BEC proliferation, and that severe ablation (A36h) enhanced only BEC proliferation since only few hepatocytes survived (Figure 3D). These proliferation patterns suggest that the extent of liver damage influences whether hepatocytes or BECs proliferate and thus which of these cell types is the primary contributor to liver regeneration.

BECs can extensively give rise to regenerating hepatocytes upon severe hepatocyte ablation

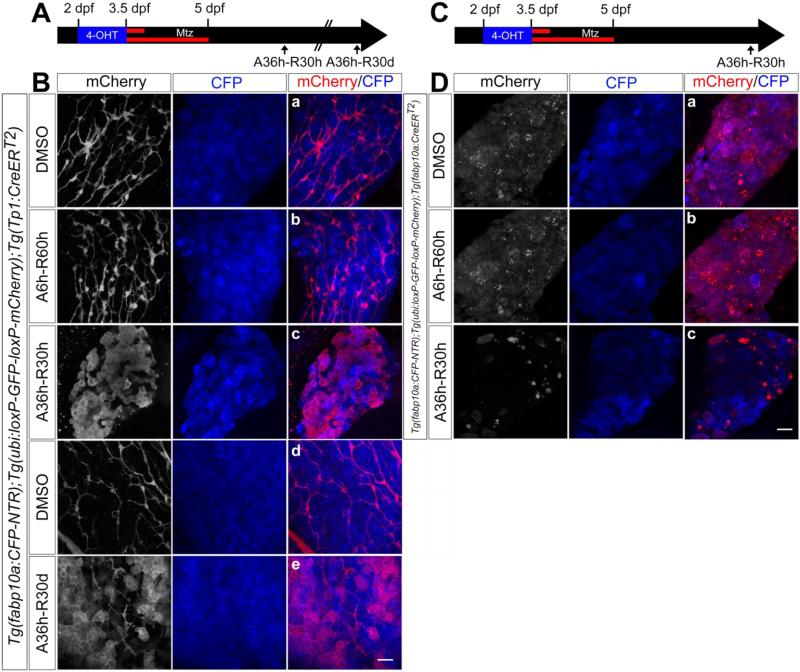

Weak Tp1:H2B-mCherry expression in Alcam− cells in the regenerating liver at A36h-R24h (Figure 2Be, arrowheads) suggested the possibility that BECs were the origin of the regenerating hepatocytes. We sought to confirm whether BECs extensively contributed to the regenerating hepatocyte population using Cre/loxP-mediated permanent lineage tracing. To trace the BEC lineage, we used the Tg(Tp1:CreERT2)s951 line which expresses CreERT2 in BECs27, and together with a Cre reporter line13, Tg(ubi:loxP-GFP-loxP-mCherry)cz1701, labels BECs with mCherry expression (Supplementary Figure 5A). Tg(fabp10a:CFP-NTR);Tg(ubi:loxP-GFP-loxP-mCherry);Tg(Tp1:CreERT2) embryos were treated with 4-OHT from 2 dpf for 36 hours to label BECs, which resulted in the labeling of 96±3% BECs (Supplementary Figure 5B-5D), before hepatocyte ablation by Mtz treatment (Figure 4A). Upon severe hepatocyte ablation (A36h), mCherry expression was observed in most CFP+ hepatocytes at A36h-R30h (Figure 4Bc), whereas upon moderate hepatocyte ablation (A6h), it was not observed in CFP+ hepatocytes but in Alcam+ BECs (Figure 4Bb and data not shown). If BEC-derived hepatocytes were not fully functional, they should be replaced by fully functional hepatocytes that were not derived from BECs as the larvae grow. However, we found that mCherry+ hepatocytes were still detected 30 days after severe hepatocyte ablation (Figure 4Be), suggesting that BEC-derived hepatocytes are fully functional.

Figure 4.

Severe hepatocyte ablation results in extensive BEC contribution to hepatocytes. (A, C) Scheme illustrating the permanent lineage tracing of BECs (A) or hepatocytes (C) upon moderate (A6h) or severe (A36h) hepatocyte ablation. (B, D) Confocal images of the regenerating liver immunostained for mCherry and processed for fluorescence detection of the fabp10a:CFP-NTR transgene (blue). The Tg(Tp1:CreERT2) and Tg(fabp10a:CreERT2) lines were used to trace the lineage of BECs (B) and hepatocytes (D), respectively. Embryos were treated with 4-OHT from 2 to 3.5 dpf followed by Mtz treatment for 6 (Bb and Db) or 36 (Bc, Be and Dc) hours. Scale bars, 20 μm.

Although most regenerating hepatocytes were derived from BECs after A36h (Figure 4Bc), we could not rule out the possibility that some hepatocytes that escaped the ablation significantly contributed to regenerating hepatocytes. To test this possibility, we generated the Tg(fabp10a:CreERT2) line that expresses CreERT2 in hepatocytes and traced their lineage during liver regeneration (Figure 4C). 4-OHT treatment from 2 dpf for 36 hours resulted in the labeling of 93±2% hepatocytes (Supplementary Figure 5B-5D). mCherry expression was observed in a small subset of CFP+ hepatocytes in the regenerating liver at A36h-R30h (Figure 4Dc), whereas it was observed in most CFP+ hepatocytes in control livers (Figure 4Da), indicating that preexisting hepatocytes minimally contributed to regenerating hepatocytes upon severe hepatocyte ablation.

Given the correlation between the extent of hepatocyte ablation and the proliferation patterns of hepatocytes and BECs (Figure 3D), we sought to determine whether the correlation extended to the cell types that gave rise to regenerating hepatocytes. Upon moderate hepatocyte ablation (A6h), there were no BEC-derived mCherry+ hepatocytes at A6h-R60h, whereas most hepatocytes were hepatocyte-derived (Figure 4Bb versus 4Db), consistent with the finding that only hepatocyte proliferation increased at A5h (Figure 3D). Upon intermediate hepatocyte ablation (A18h, Supplementary Figure 5E), both BEC- and hepatocyte-derived mCherry+ hepatocytes were observed at A18h-R48h (Supplementary Figure 5F), consistent with the finding that both BEC and hepatocyte proliferation increased at A18h (Figure 3D). Altogether, these data reveal a correlation between the extent of hepatocyte ablation, BEC proliferation, and BEC contribution to regenerating hepatocytes.

BECs dedifferentiate into hepatoblast-like cells (HB-LCs) and subsequently redifferentiate into hepatocytes upon severe hepatocyte ablation

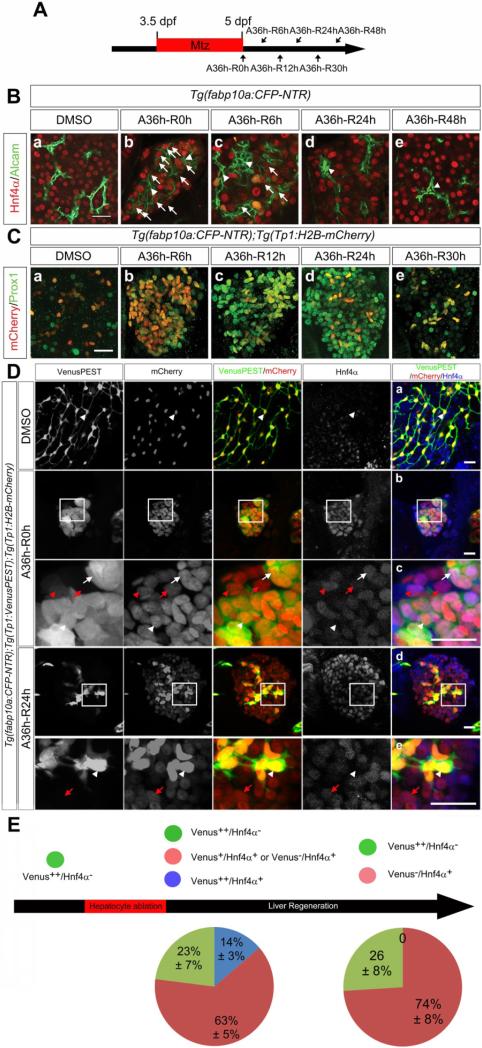

To determine how BECs gave rise to hepatocytes, we examined the expression of the hepatoblast/hepatocyte marker Hnf4α28, which is not expressed in BECs, and the earliest hepatoblast marker Prox129 that is later expressed in both hepatocytes and BECs18. Hnf4α was expressed in hepatocytes, but not in Alcam+ BECs, in control livers (Figure 5Ba), whereas it was expressed in many Alcam+ cells at A36h-R0h (Figure 5Bb, arrows). These Hnf4α/Alcam double-positive cells were still detected at A36h-R6h (Figure 5Bc, arrows), but not at A36h-R24h or A36h-R48h (Figure 5Bd-5Be). Prox1 expression was observed in a subset of hepatocytes and in most BECs in control livers at 5-7 dpf (Figure 5Ca and data not shown); however, it was greatly enhanced in all Tp1:H2B-mCherry+ cells (Figure 5Cb) and all newly generated hepatocytes at least until A36h-R24h (Figure 5Cb-5Cd and Supplementary Figure 6A). As liver regeneration proceeded, Prox1 expression level and pattern became similar to those observed in controls (Figure 5Ce). Since zebrafish hepatoblasts express Hnf4α, Prox1 and Alcam18, 28, we considered these triple-positive cells, which temporarily appeared during liver regeneration, to be HB-LCs, similar to oval cells in rodent oval cell activation models. Although HB-LCs are the equivalent of oval cells, hepatic progenitor cells, and hepatobiliary stem/progenitor cells in mammals, we used this terminology because Hnf4α is not expressed in oval cells and there are no oval cell markers currently available in zebrafish.

Figure 5.

BECs appear to dedifferentiate into HB-LCs and subsequently redifferentiate into hepatocytes in BEC-driven liver regeneration. (A) Scheme illustrating the periods of Mtz treatment and liver regeneration. (B) Confocal images of the regenerating liver immunostained for Alcam (green) and Hnf4α (red). Arrows point to Alcam+;Hnf4α+ cells; arrowheads point to Alcam+;Hnf4α− cells. (C) Confocal images of the regenerating liver immunostained for Prox1 (green) and processed for fluorescence detection of the Tp1:H2B-mCherry transgene (red). (D) Confocal images of the regenerating liver immunostained for Hnf4α and processed for fluorescence detection of the Tp1:VenusPEST and Tp1:H2B-mCherry transgenes. Arrowheads, arrows, red arrowheads, and red arrows point to Venus++/Hnf4α−, Venus++/Hnf4α+, Venus+/Hnf4α+, and Venus−/Hnf4α+ cells, respectively. Dc and De are enlarged images of the boxes in Db and Dd, respectively. (E) Diagram illustrating the percentage of each group as shown in D. Scale bars, 20 μm.

We used the Tg(Tp1:H2B-mCherry) and Tg(Tp1:VenusPEST) lines24 to better reveal the transition process from BECs to hepatocytes. Since H2B makes its fusion protein very stable30 and PEST makes its fusion protein rapidly degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway31, these two lines allowed us to distinguish BECs (Venus++) from BEC-derived and newly generated hepatocytes (Venus+ or Venus−) based on the fluorescence intensity from these two proteins. All mCherry-expressing cells in control livers strongly expressed both H2B-mCherry and VenusPEST, but did not express Hnf4α at all (Figure 5Da, arrowheads, Venus++/mCherry++/Hnf4α−). However, mCherry-expressing cells at A36h-R0h were roughly divided into four groups based on Venus intensity and Hnf4α expression: Venus++/Hnf4α−, Venus++/Hnf4α+, Venus+/Hnf4α+, and Venus−/Hnf4α+ cells (white arrowheads, white arrows, red arrowheads, and red arrows, respectively, in Figure 5Dc). At A36h-R24h, mCherry-expressing cells were clearly divided into two groups: Venus++/Hnf4α− and Venus−/Hnf4α+ cells (white arrowheads and red arrows, respectively, in Figure 5De). At these two time points, Prox1 was expressed in all mCherry-expressing cells (data not shown). Since BECs (Venus++/Hnf4α−) appeared to give rise to newly generated hepatocytes (Venus−/Hnf4α+) through Venus++/Hnf4α+ and Venus+/Hnf4α+ cells, these intermediate cells, especially Venus++/Hnf4α+ cells, might represent HB-LCs. Such cells were detected at A36h-R0h but not at A36h-R24h (Figure 5E, blue, 14±3% versus 0%), implying that they had already differentiated into hepatocytes or BECs at A36h-R24h. Altogether, these data reveal that upon severe hepatocyte ablation, BECs dedifferentiate into HB-LCs, which subsequently redifferentiate into hepatocytes.

BEC-driven liver regeneration is compromised in wnt2bb mutants

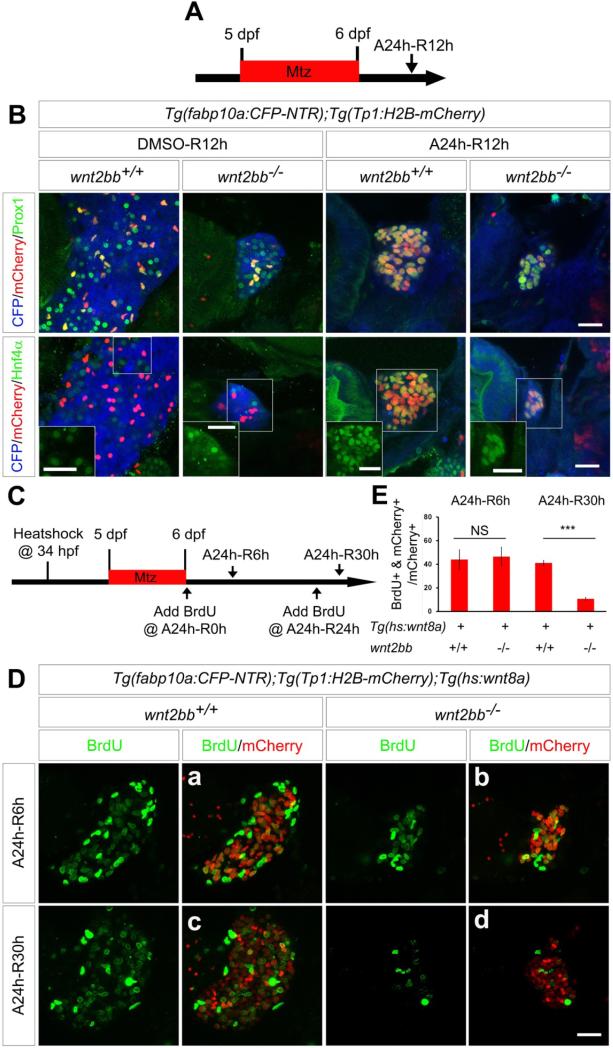

To begin to understand the molecular mechanisms underlying BEC-driven liver regeneration, we examined liver regeneration in wnt2bb mutants upon severe hepatocyte ablation. Since Wnt/β-catenin signaling is implicated in liver development and regeneration32 and zebrafish wnt2bb mutants exhibit delayed liver growth29, 33, we speculated that BEC-driven liver regeneration might be impaired in wnt2bb mutants. Because liver size in wnt2bb mutants is smaller than in controls but continues to grow29, 33, larvae were treated with Mtz from 5 dpf as well as from 3.5 dpf. Both A36h from 3.5 dpf (Supplementary Figure 7) and A24h from 5 dpf (Figure 6) resulted in severe hepatocyte ablation. Upon ablation, strong CFP expression was detected in wnt2bb mutants as in wild-types; however, mutant liver size was greatly reduced compared to wild-type at A36h-R30h and A36h-R54h (Supplementary Figure 7B), suggesting that wnt2bb plays a critical role in BEC-driven liver regeneration. However, there was a possibility that the regeneration defect observed in wnt2bb mutants was simply due to the smaller size of their liver before ablation. To test this possibility, we used the Tg(hs:wnt8a)w34 line that expresses Wnt8a under the heat-shock promoter34, which allows for the rescue of liver defects in wnt2bb mutants35. Although Wnt8a overexpression via heat-shock at 34 hpf substantially rescued liver size in wnt2bb mutants, the size of the regenerating liver in the rescued wnt2bb mutants was still much smaller than in controls (Supplementary Figure 8B), further indicating a role for wnt2bb in BEC-driven liver regeneration.

Figure 6.

BEC-driven liver regeneration is compromised in wnt2bb mutants. (A) Scheme illustrating the periods of Mtz treatment and liver regeneration. (B) Confocal images of the regenerating liver in wild-type or wnt2bb−/− larvae immunostained for Prox1 or Hnf4α (green) and processed for fluorescence detection of the fabp10a:CFP-NTR (blue) and Tp1:H2B-mCherry (red) transgenes. Hnf4α single-labeling images of the boxed regions are shown in insets to clearly show Hnf4α expression in H2B-mCherry+ cells. (C) Scheme illustrating the times of heat-shock and BrdU treatment and the periods of Mtz treatment and liver regeneration. (D) Confocal images of the regenerating liver in wild-type and wnt2bb−/− larvae in which Wnt8a was temporarily overexpressed via a single heat-shock at 34 hpf. The larvae were immunostained for BrdU (green) and mCherry (red). (E) A graph showing the percentage of BrdU+ cells among H2B-mCherry+ cells during liver regeneration as shown in D. Error bars, ±SD; asterisks, P<0.00001; NS, not statistically significant. Scale bars, 20 μm.

Since failure in dedifferentiation, redifferentiation, or proliferation could result in liver regeneration defects, we sought to determine the reason for impaired BEC-driven liver regeneration in wnt2bb mutants. Both Prox1 and Hnf4α were expressed in Tp1:H2B-mCherry+ cells in wnt2bb mutants at A24h-R12h, as in controls (Figure 6B), suggesting that the dedifferentiation of BECs into HB-LCs was not defective in wnt2bb mutants. In addition, strong fabp10a:CFP-NTR expression in wnt2bb mutants (Supplementary Figure 7B) indicates that the redifferentiation of HB-LCs into hepatocytes was not defective. To determine whether proliferation was altered in wnt2bb mutants, we performed BrdU proliferation assays in rescued wnt2bb mutants (Figure 6C). Tp1:H2B-mCherry+ cells were detected by mCherry immunostaining instead of intrinsic fluorescence to reveal newly generated hepatocytes as well as BECs at R30h. The percentage of BrdU+ cells among Tp1:H2B-mCherry+ cells in the rescued wnt2bb mutants at A24h-R6h was similar to controls (Figure 6Db versus 6Da), whereas it was greatly reduced in the rescued wnt2bb mutants at A24h-R30h compared to controls (Figure 6Dd versus 6Dc). These proliferation data together with the expression data suggest that the proliferation of newly generated hepatocytes is impaired in wnt2bb mutants during BEC-driven liver regeneration.

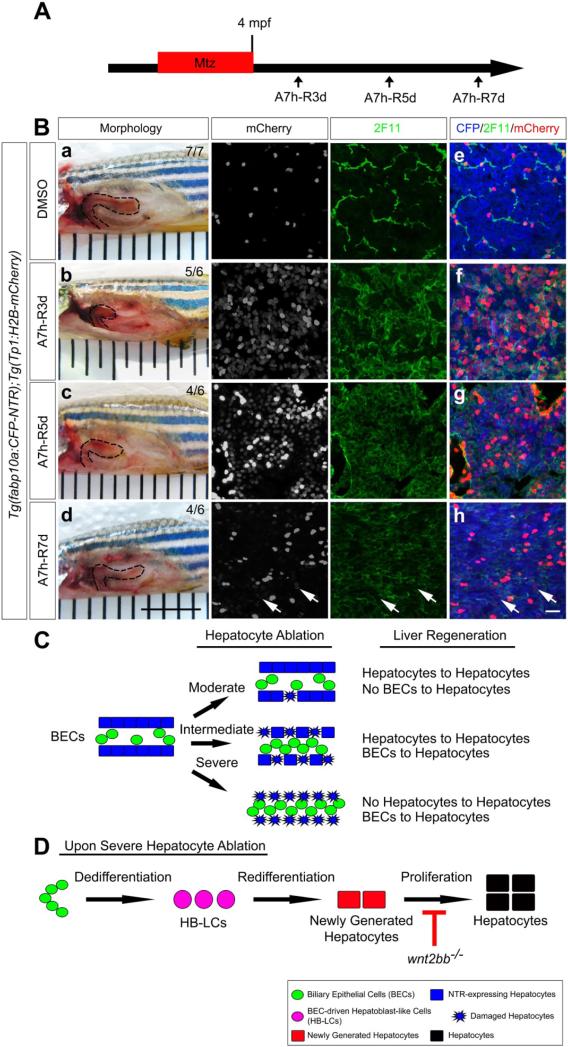

BECs can extensively give rise to hepatocytes in adults

Although our data demonstrate the conversion of BECs to hepatocytes upon severe hepatocyte ablation in larvae, it was not clear whether this conversion could still occur in adults, given the general notion that the regenerative capacity of organs or tissues is reduced as animals age. To this end, 4-month old adult zebrafish containing the fabp10a:CFP-NTR and Tp1:H2B-mCherry transgenes were treated with 5mM Mtz for 7 hours (longer treatment killed the fish), and their livers were dissected out 3-7 days later for subsequent analyses (Figure 7A). Upon 7-hour Mtz treatment (A7h), liver size was greatly reduced and the liver appeared to shrink from its posterior end at A7h-R3d (Figure 7Bb, dashed line). Later, liver size recovered (Figure 7Bc-7Bd, dashed lines) although such recovery was much slower in adults than in larvae. To detect BECs in adults, we examined the expression of the 2F11 antigen, a BEC marker18, as well as Tp1:H2B-mCherry, another BEC-specific marker, in control livers (Figure 7Be). The number and density of double-positive cells dramatically increased at A7h-R3d and then gradually decreased at A7h-R5d and A7h-R7d (Figure 7Bf-7Bh). Moreover, the number of the proliferation marker PCNA and Tp1:H2B-mCherry double-positive cells greatly increased at A7h-R3d and then gradually decreased, whereas such double-positive cells were barely detected in control livers (Supplementary Figure 9). Importantly, a number of strong fabp10a:CFP-NTR+ hepatocytes weakly expressed Tp1:H2B-mCherry at A7h-R5d and more weakly at A7h-R7d (Figure 7Bg-7Bh and Supplementary Figure 10, arrows), indicating the BEC origin of these hepatocytes.

Figure 7.

BECs give rise to hepatocytes in adult zebrafish as well as in larvae. (A) Scheme illustrating the periods of Mtz treatment and liver regeneration. (B) Liver morphology (dashed lines) of 4 month-old adults treated with DMSO (Ba) or Mtz (Bb-Bd). Confocal images of the dissected liver processed for section immunostaining with 2F11 (Be-Bh) (green) and for fluorescence detection of the fabp10a:CFP-NTR (blue) and Tp1:H2B-mCherry (red) transgenes (Be-Bh). Arrows point to faint H2B-mCherry+ cells expressing strong CFP-NTR (Bh). Scale bars, 6.35 mm (Ba-Bd); 20 μm (Be-Bh). (C) Cartoon summarizing our findings that the severity of hepatocyte ablation determines the relative contribution of BECs and hepatocytes to the regenerating hepatocytes. (D) A model of BEC-driven liver regeneration in zebrafish.

Discussion

In this study, we provide several lines of evidence that BECs can extensively give rise to hepatocytes, thereby resulting in recovery from severe liver damage. First, the short-term lineage tracing of BECs, based on the stability of H2B-mCherry, showed that hepatocytes in the regenerating liver faintly expressed Tp1:H2B-mCherry, indicating their BEC origin. Second, the Cre/loxP lineage tracing of BECs and hepatocytes showed that most hepatocytes in the regenerating liver were derived from BECs, but not from preexisting hepatocytes. Last, liver marker analysis combined with the expression analysis of Tp1:H2B-mCherry and Tp1:VenusPEST showed that HB-LCs, which express Hnf4α, Alcam and VenusPEST, were transiently present during BEC-driven liver regeneration. Although all these experiments were performed in larvae, the short-term lineage tracing of BECs in adults importantly showed that many hepatocytes in the regenerating liver also expressed Tp1:H2B-mCherry, indicating that BECs can extensively give rise to hepatocytes in adults as well.

It has been proposed that if hepatocyte proliferation is compromised, BECs give rise to hepatocytes and thereby contribute to recovery from liver damage1, 2, 36. However, recent Cre/loxP lineage-tracing studies in mice make this a controversial concept. One study showed that BECs contributed significantly to the hepatocyte population in certain liver injury models and even during homeostasis9. In contrast, several other liver injury studies showed that BECs minimally contributed to the hepatocyte population10-12. Furthermore, the lineage tracing of Foxl1-37 or Lgr5-38 positive cells, whose expression is barely detected in the normal liver but dramatically induced in oval cells, only revealed a small contribution of Foxl1+ or Lgr5+ oval cells to hepatocytes. However, it was speculated that a more substantial conversion of BECs to hepatocytes might be detected if more severe injury models were used. Our findings demonstrate that the severity of hepatocyte ablation influences the extent of BEC contribution to hepatocytes and are in parallel with a recent report on pancreas regeneration in mice. Extreme ablation of adult pancreatic β-cells leads to α- to β-cell transdifferentiation, whereas milder ablation leads to β-cell proliferation39.

As a first step towards understanding BEC-driven liver regeneration at the molecular level, we investigated the role of wnt2bb, which has been implicated in hepatoblast specification29, 40, in this process. We found that the proliferation of newly generated hepatocytes, but not the dedifferentiation of BECs or subsequent redifferentiation into hepatocytes, was impaired in wnt2bb mutants during BEC-driven liver regeneration. Wnt/β-catenin signaling has also been implicated in BEC-driven liver regeneration in rodents32. Liver-specific β-catenin knockout mice exhibit a dramatic decrease in oval cell numbers upon 3,5-diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine diet, suggesting its role in the activation and proliferation of hepatic progenitor cells41. Although we did not find such defects in wnt2bb mutants, it is possible that other Wnt ligands, such as Wnt2 which has also been implicated in hepatoblast specification in zebrafish40, may regulate the proliferation of BECs and HB-LCs. In line with this possibility, a recent paper reported that in mouse, WNT2 from liver sinusoidal endothelial cells promotes hepatic proliferation upon partial hepatectomy thereby contributing to liver regeneration42.

Our model is unique because of the extensive contribution of BECs, but minor contribution of preexisting hepatocytes, to regenerated hepatocytes upon severe hepatocyte ablation. However, upon intermediate hepatocyte ablation (A18h from 3.5 dpf), BECs significantly contributed to regenerated hepatocytes, but surviving hepatocytes also contributed to liver regeneration (Figure 7C). BEC-driven liver regeneration appears to proceed through the following steps: BEC proliferation is first enhanced as these cells dedifferentiate into HB-LCs that subsequently proliferate and redifferentiate into newly generated hepatocytes (Figure 7D). This process is quite similar to that proposed based on studies of rodent injury models in which oval cells are utilized instead of HB-LCs36; thus, HB-LCs in our model may be considered as oval-like cells. The zebrafish liver is replete with bile preductules positioned between the canaliculi and bile ductules in the biliary tree, and bile preductular epithelial cells (BPDECs) comprise the majority of BECs in the zebrafish liver. Bile preductules are considered the equivalent of the canals of Hering in mammals because BPDECs directly contact hepatocytes and have no basal lamina43. This structural feature of the zebrafish liver may contribute to the extensive biliary conversion to hepatocytes upon severe hepatocyte ablation.

The correlation between disease severity and oval cell numbers in chronic human liver diseases44 suggests that BEC-driven liver regeneration may be initiated to recover liver function in patients. However, activated oval cells in humans fail to extensively give rise to hepatocytes, thereby resulting in the failure of liver recovery. Therapeutic enhancement of BEC-driven liver regeneration in patients might improve liver recovery by making hepatocytes from oval cells. Thus, findings from our model may provide new insights into molecular pathways used to augment this process in patients with severe liver diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Geoffrey Burns for the Tol2 destination vector pDestTol2pA2AC and Mehwish Khaliq, Neil Hukriede, Michael Tsang, and Andrew Duncan for discussions and critical reading of the manuscript.

Grant Support: The work was supported in part by grants from the American Liver Foundation and the March of Dimes Foundation (5-FY12-39) to D.S. and from the NIH (DK60322) and Packard foundation to D.Y.R.S.

Abbreviations

- BEC

biliary epithelial cell

- BPDEC

bile preductular epithelial cell

- CFP

cyan fluorescent protein

- cp

ceruloplasmin

- dpf

days post-fertilization

- gc

group-specific component

- HB-LCs

hepatoblast-like cells

- hpf

hours post-fertilization

- Mtz

metronidazole

- NTR

nitroreductase

- 4-OHT

4-hydroxytamoxifen

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions:

T.Y.C: study concept and design; acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data; writing the manuscript

N.N.: material support

D.Y.R.S.: material support; critical revision of the manuscript

D.S.: study concept and design; interpretation of data; study supervision; writing the manuscript

Disclosures: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Fausto N, Campbell JS. The role of hepatocytes and oval cells in liver regeneration and repopulation. Mechanisms of Development. 2003;120:117–130. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00338-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duncan AW, Dorrell C, Grompe M. Stem Cells and Liver Regeneration. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:466–481. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.05.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okabe M, Tsukahara Y, Tanaka M, et al. Potential hepatic stem cells reside in EpCAM(+) cells of normal and injured mouse liver. Development. 2009;136:1951–1960. doi: 10.1242/dev.031369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dorrell C, Erker L, Schug J, et al. Prospective isolation of a bipotential clonogenic liver progenitor cell in adult mice. Genes & Development. 2011;25:1193–1203. doi: 10.1101/gad.2029411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shin S, Walton G, Aoki R, et al. Foxl1-Cre-marked adult hepatic progenitors have clonogenic and bilineage differentiation potential. Genes & Development. 2011;25:1185–1192. doi: 10.1101/gad.2027811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evarts RP, Nagy P, Nakatsukasa H, et al. In vivo Differentiation of Rat-Liver Oval Cells into Hepatocytes. Cancer Res. 1989;49:1541–1547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Golding M, Sarraf CE, Lalani EN, et al. Oval Cell-Differentiation into Hepatocytes in the Acetylaminofluorene-Treated Regenerating Rat-Liver. Hepatology. 1995;22:1243–1253. doi: 10.1016/0270-9139(95)90635-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoon SM, Gerasimidou D, Kuwahara R, et al. Epithelial Cell Adhesion Molecule (EpCAM) Marks Hepatocytes Newly Derived from Stem/Progenitor Cells in Humans. Hepatology. 2011;53:964–973. doi: 10.1002/hep.24122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furuyama K, Kawaguchi Y, Akiyama H, et al. Continuous cell supply from a Sox9-expressing progenitor zone in adult liver, exocrine pancreas and intestine. Nature Genetics. 2011;43:34–41. doi: 10.1038/ng.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carpentier R, Suner RE, van Hul N, et al. Embryonic Ductal Plate Cells Give Rise to Cholangiocytes, Periportal Hepatocytes, and Adult Liver Progenitor Cells. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1432–1438. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malato Y, Naqvi S, Schurmann N, et al. Fate tracing of mature hepatocytes in mouse liver homeostasis and regeneration. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2011;121:4850–4860. doi: 10.1172/JCI59261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Espanol-Suner R, Carpentier R, Van Hul N, et al. Liver Progenitor Cells Yield Functional Hepatocytes in Response to Chronic Liver Injury in Mice. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1564–1575. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mosimann C, Kaufman CK, Li P, et al. Ubiquitous transgene expression and Cre-based recombination driven by the ubiquitin promoter in zebrafish. Development. 2011;138:169–77. doi: 10.1242/dev.059345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pisharath H, Rhee JM, Swanson MA, et al. Targeted ablation of beta cells in the embryonic zebrafish pancreas using E. coli nitroreductase. Mech Dev. 2007;124:218–29. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Curado S, Anderson RM, Jungblut B, et al. Conditional targeted cell ablation in zebrafish: A new tool for regeneration studies. Developmental Dynamics. 2007;236:1025–1035. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Curado S, Stainier DYR, Anderson RM. Nitroreductase-mediated cell/tissue ablation in zebrafish: a spatially and temporally controlled ablation method with applications in developmental and regeneration studies. Nature Protocols. 2008;3:948–954. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerloff T, Stieger B, Hagenbuch B, et al. The sister of P-glycoprotein represents the canalicular bile salt export pump of mammalian liver. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:10046–50. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.16.10046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sakaguchi TF, Sadler KC, Crosnier C, et al. Endothelial signals modulate hepatocyte apicobasal polarization in zebrafish. Curr Biol. 2008;18:1565–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.08.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farber SA, Pack M, Ho SY, et al. Genetic analysis of digestive physiology using fluorescent phospholipid reporters. Science. 2001;292:1385–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1060418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hellman NE, Gitlin JD. Ceruloplasmin metabolism and function. Annual Review of Nutrition. 2002;22:439–458. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.22.012502.114457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Noel ES, dos Reis M, Arain Z, et al. Analysis of the Albumin/alpha-Fetoprotein/Afamin/Group specific component gene family in the context of zebrafish liver differentiation. Gene Expression Patterns. 2010;10:237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.gep.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gut P, Baeza-Raja B, Andersson O, et al. Whole-organism screening for gluconeogenesis identifies activators of fasting metabolism. Nature Chemical Biology. 2013;9:97–104. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zaret KS, Grompe M. Generation and regeneration of cells of the liver and pancreas. Science. 2008;322:1490–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1161431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ninov N, Borius M, Stainier DYR. Different levels of Notch signaling regulate quiescence, renewal and differentiation in pancreatic endocrine progenitors. Development. 2012;139:1557–1567. doi: 10.1242/dev.076000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lorent K, Moore JC, Siekmann AF, et al. Reiterative use of the notch signal during zebrafish intrahepatic biliary development. Dev Dyn. 2010;239:855–64. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Delous M, Yin C, Shin D, et al. Sox9b is a key regulator of pancreaticobiliary ductal system development. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002754. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ninov N, Hesselson D, Gut P, et al. Metabolic Regulation of Cellular Plasticity in the Pancreas. Current Biology. 2013;23:1242–1250. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Field HA, Ober EA, Roeser T, et al. Formation of the digestive system in zebrafish. I. Liver morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 2003;253:279–90. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(02)00017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ober EA, Verkade H, Field HA, et al. Mesodermal Wnt2b signalling positively regulates liver specification. Nature. 2006;442:688–91. doi: 10.1038/nature04888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brennand K, Huangfu D, Melton D. All beta cells contribute equally to islet growth and maintenance. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e163. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Madrigal Pulido J, Padilla Guerrero I, Magana Martinez Ide J, et al. Isolation, characterization and expression analysis of the ornithine decarboxylase gene (ODC1) of the entomopathogenic fungus, Metarhizium anisopliae. Microbiol Res. 2011;166:494–507. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nejak-Bowen KN, Monga SPS. Beta-catenin signaling, liver regeneration and hepatocellular cancer: Sorting the good from the bad. Seminars in Cancer Biology. 2011;21:44–58. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shin D, Weidinger G, Moon RT, et al. Intrinsic and extrinsic modifiers of the regulative capacity of the developing liver. Mechanisms of Development. 2012;128:525–535. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weidinger G, Thorpe CJ, Wuennenberg-Stapleton K, et al. The Sp1-related transcription factors sp5 and sp5-like act downstream of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in mesoderm and neuroectoderm patterning. Curr Biol. 2005;15:489–500. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shin D, Lee Y, Poss KD, et al. Restriction of hepatic competence by Fgf signaling. Development. 2011;138:1339–1348. doi: 10.1242/dev.054395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Michalopoulos GK. Liver regeneration: Alternative epithelial pathways. International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 2011;43:173–179. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sackett SD, Li ZD, Hurtt R, et al. Foxl1 Is a Marker of Bipotential Hepatic Progenitor Cells in Mice. Hepatology. 2009;49:920–929. doi: 10.1002/hep.22705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huch M, Dorrell C, Boj SF, et al. In vitro expansion of single Lgr5+ liver stem cells induced by Wnt-driven regeneration. Nature. 2013;494:247–50. doi: 10.1038/nature11826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thorel F, Nepote V, Avril I, et al. Conversion of adult pancreatic alpha-cells to beta-cells after extreme beta-cell loss. Nature. 2010;464:1149–1154. doi: 10.1038/nature08894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poulain M, Ober EA. Interplay between Wnt2 and Wnt2bb controls multiple steps of early foregut-derived organ development. Development. 2011;138:3557–3568. doi: 10.1242/dev.055921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Apte U, Thompson MD, Cui SS, et al. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling mediates oval cell response in rodents. Hepatology. 2008;47:288–295. doi: 10.1002/hep.21973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ding BS, Nolan DJ, Butler JM, et al. Inductive angiocrine signals from sinusoidal endothelium are required for liver regeneration. Nature. 2010;468:310–315. doi: 10.1038/nature09493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yao YL, Lin JX, Yang P, et al. Fine Structure, Enzyme Histochemistry, and Immunohistochemistry of Liver in Zebrafish. Anatomical Record-Advances in Integrative Anatomy and Evolutionary Biology. 2012;295:567–576. doi: 10.1002/ar.22416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lowes KN, Brennan BA, Yeoh GC, et al. Oval cell numbers in human chronic liver diseases are directly related to disease severity. American Journal of Pathology. 1999;154:537–541. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65299-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.