Abstract

The purpose of this article is to describe a conceptual model of methods used to develop culturally focused interventions. We describe a continuum of approaches ranging from nonadapted/surface-structure adapted programs to culturally grounded programs, and present recent examples of interventions resulting from the application of each of these approaches. The model has implications for categorizing culturally focused prevention efforts more accurately, and for gauging the time, resources, and level of community engagement necessary to develop programs using each of the different methods. The model also has implications for funding decisions related to the development and evaluation of programs, and for planning of participatory research approaches with community members.

Keywords: Cultural adaptation, Culturally grounded prevention, Community-based participatory research, Health disparities

The social/behavioral intervention literature has increasingly focused on interventions tailored to specific ethnocultural groups. This literature has developed largely in the area of treatment, and has adhered predominantly to a framework of adapting evidence-based interventions to reflect the cultural and social norms of specific ethnic groups (Hwang, 2009; Lau, 2006). The field of prevention has similarly adopted the lexicon and framework of cultural adaptation; however, this term is presently being used to describe a wide variety of practices in the field of prevention (Deschine et al., 2013; Dustman, & Kulis, 2013; Kulis & Dustman, 2013; Sims, Beltangady, Gonzalez, Whitesell, & Castro, 2013). As a result, there is a lack of understanding related to the level and depth in which culturally focused interventions reflect the worldviews of the populations they are intended to serve, and the resources and efforts that are being used to develop these interventions.

In this article, we describe a model for developing culturally focused prevention interventions for specific ethnocultural populations that is based on the prevention literature in minority health and health disparities. Specifically, this article categorizes literature on a continuum from culturally adapted to grounded approaches, provides examples of interventions developed using each type of approach, and describes the strengths and limitations of adhering to each approach. This article is intended to provide a more accurate representation of recent efforts toward developing prevention interventions for minority populations currently described in the literature. It has implications for funding agencies and communities, in terms of decision-making related to investments in the development of different prevention efforts.

A Model for Developing Culturally Focused Prevention Interventions

The term “cultural adaptation” is widely recognized in the field of prevention, and various stage models have been described that specify the process of adapting interventions to specific cultural groups (see Castro, Barrera, & Holleran Steiker, 2010; McKleroy et al., 2006; Sims et al., 2013). Inherent in these models is the adoption of an empirically supported intervention as the foundation for another intervention tailored for a cultural group that is different from the group(s) for whom the original intervention was developed. The practice of cultural adaptation can range from minor modifications, such as changes to the images and terms used in the curriculum (surface structure changes), to more substantial changes that reflect complex cultural phenomena that are more closely intertwined with core prevention components (deep-structure adaptations; Castro, Barrera, & Martinez, 2004; Resnicow, Soler, Braithwaite, Ahluwalia, & Butler, 2000). Far less attention has been directed toward the development of culturally grounded interventions in the prevention literature. Culturally grounded interventions have been designed from the “ground up” (that is, starting from the values, behaviors, norms, and worldviews of the populations they are intended to serve), and therefore are most closely connected to the lived experiences and core cultural constructs of the targeted populations and communities. Table 1 describes these different approaches to developing culturally focused prevention, including the strengths and limitations of each approach. The next section of this article will elucidate these strengths and limitations and provide examples of programs that reflect each of the approaches toward developing culturally focused prevention interventions.

Table 1.

Strengths and Limitations of Approaches in Developing Culturally Focused Interventions

| Culturally Grounded Prevention | Deep-Structure Cultural Adaptation | Non-Adaptation/Surface-Structure Cultural Adaptation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strengths | Limitations | Strengths | Limitations | Strengths | Limitations |

| Community is engaged and invested in the development of the program | Time consuming | Based on empirically supported intervention principles | Assumes the core components of an evidence-based program are applicable across cultural groups | Tests the applicability of generic/universal prevention principles to unique groups | Often unacceptable to or disconnected from the community |

| Directly addresses core cultural constructs | Expensive | Balances length of time and costs to develop curriculum with the ability to bring the program to scale | Need to specify and retain the core prevention components for fidelity | Faster to develop, implement, and bring to scale | Can potentially avoid core cultural components |

| Core prevention components are derived organically (from the “ground up”) and can therefore be intertwined with core cultural components | Difficult to evaluate and replicate in similar settings | Engages the community, but within the parameters of a specific evidence-based program | May inadvertently alter core components and decrease their effectiveness | Based on empirically supported interventions, but with questionable “fit” | |

Non-Adapted Programs and Surface-Structure Cultural Adaptations

One option for prevention interventionists and researchers is to either implement a universal, selective, or indicated prevention program without any modifications to the unique, targeted cultural groups, or to adapt the surface structure of a prevention program, such as making changes to images or phrases throughout its content or lessons, in order to align the program more with familiar concepts or references of a specific cultural group. Both of these approaches bear consideration for several reasons. Culturally adapted approaches are much less expensive and much less time intensive to develop than culturally grounded approaches, and they are faster to bring to scale and thereby exert a public health impact (Holleran Steiker et al., 2008; Okamoto et al., 2012). This is particularly relevant for populations that may not necessarily need culturally specific prevention components to achieve positive outcomes. For example, Fang and Schinke (2013) recently found that a culturally generic, family based substance abuse prevention curriculum for Asian American girls had promising results (e.g., increased use of drug resistance strategies, improved self efficacy, and lower intentions to use substances in the future). Delivered in an online format, this program has the potential to be brought to scale faster and thereby have a wide-scale preventive impact on this population. Non-adapted or surface-structure adapted programs also can be used as an intermediary step in the process of creating deep-structure cultural adaptations of existing programs. For example, Deschine et al. (2013) recently described the process of creating the Parenting in 2 Worlds Curriculum for urban American Indian families of the Southwest U.S. This process involved the implementation of a generic prevention curriculum, which was closely evaluated in multiple sites and then culturally adapted in later phases of the adaptation process. The benefit of this approach is that specific prevention components needing adaptation can be identified, modified, pilot tested, and examined in a final version of the curriculum (Ringwalt & Bliss, 2006).

Several empirically supported universal prevention programs, such as Life Skills Training (Botvin, Schinke, Epstein, & Diaz, 1994; Botvin, Schinke, Epstein, Diaz, & Botvin, 1995) and The Strengthening Families Program (Kumpfer, Alvarado, Smith, & Bellamy, 2002; Kumpfer, Pinyuchon, de Melo, & Whiteside, 2008) have been adapted to fit the norms and values of specific ethnocultural groups. These studies have reported mixed findings, and have prompted the examination of issues of fidelity versus “fit” of adapted prevention programs (Castro et al., 2004). Part of the issue in cultural adaptations which may have contributed to their mixed findings is the difficulty in identifying the core components of empirically supported prevention programs, which are necessary to help guide the process of adaptation (Sims et al., 2013). Without knowledge of these components, interventionists and prevention researchers are forced to make conservative modifications to universal prevention programs (i.e., surface structure changes) in order to retain as much of the original intervention as possible. This ensures that the unidentified core components of empirically supported prevention programs are retained in the adapted versions, but at the risk of questionable “fit” to specific cultural groups (Castro et al., 2004). Further, communities are often resistant to adopting non-adapted programs or programs with only minor surface structure modifications. This is particularly the case for populations with an absence of prevention research to support the use of these types of programs, such as indigenous populations (Edwards, Giroux, & Okamoto, 2010).

In most cases, infusing culturally specific constructs into prevention curricula is preferred or expected. However, in instances where culturally generic or non-adapted versions of a curriculum are found to be effective, one could argue that they should be implemented to scale in order to exert a public health impact more quickly for particularly vulnerable populations. Future iterations of these generic or non-adapted curricula might examine the impact of infusing culturally specific content, to see if this content further enhances outcomes.

Deep-Structure Cultural Adaptations

Deep-structure cultural adaptations involve using systematic methods to infuse the unique cultural worldviews, beliefs, values, and behaviors of a population into a prevention curriculum that has been developed and normed on a different population. Methods to infuse complex cultural elements deep into the curriculum require much more time and close collaboration with the targeted community than does the use of non-adapted programs or programs with surface-structure adaptations. Nonetheless, deep-structure adaptations balance the cost and time to create relevant culturally focused interventions for unique cultural groups with increasing the likelihood of achieving desired program effects and the ability to bring the program to scale. Therefore, they may be a good fit for populations with immediate health-related needs and a lack of prevention research to inform or guide the adaptation process. For example, community groups and epidemiological data provide strong support that substance use/abuse disparities for American Indian populations call for an immediate response through culturally focused interventions. However, little is known as to the core prevention and cultural components that are necessary for programs targeting these populations to be effective. Deep-structure adaptations have the potential to tap into these core prevention and cultural components within an existing framework of an applicable evidence-based intervention.

An early example in the use of a deep-structure cultural adaptation was demonstrated in the development of the Zuni Life Skills Curriculum (LaFromboise & Howard-Pitney, 1995). The program was a school-based, suicide prevention curriculum targeting Zuni Pueblo adolescents of New Mexico, and focused on skills training and psychoeducation related to suicidal behavior. Initially, a culturally generic version of the program was developed from existing models of suicide prevention. However, over the course of a year, Zuni tribal members and schoolteachers adapted the curriculum to reflect Zuni values and beliefs. For example, core values such as resistance and fortitude were underscored in the curriculum (LaFromboise & Lewis, 2008). While the adaptation of the curriculum appeared to rely heavily on the expertise of cultural and tribal leaders and experts, it is unclear as to the role that Zuni youth had in the development of the adapted version of the curriculum.

Two more recent examples of programs utilizing deep-structure adaptations are the Living in 2 Worlds Curriculum (L2W; Dustman & Kulis, 2013; Jumper-Reeves, Dustman, Harthun, Kulis, & Brown, 2013; Kulis, Dustman, Brown, & Martinez, 2013) and Parenting in 2 Worlds Curriculum (P2W; Deschine et al., 2013; Kulis & Dustman, 2013). L2W is based on the keepin’ it REAL multicultural drug prevention curriculum developed for middle school youth (Hecht et al., 2003; Kulis et al., 2005; Marsiglia, Kulis, Wagstaff, Elek, & Dran, 2005), and relies on a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach to adapt the curriculum to fit the values and beliefs of urban American Indian youth. Focus groups with American Indian youth, adults, and elders were used to make substantial changes in the keepin’ it REAL program that were necessary to fit the worldviews of urban American Indian youth of the southwest. These groups described the importance of infusing Native values, traditions, and connectivity into the curricular content, as well as addressing issues related to pressures to assimilate to mainstream cultural values and the importance of maintaining tribal and cultural identities (Jumper-Reeves et al., 2013). The P2W program was based on the Families Preparing a New Generation Program (Parsai, Castro, Marsiglia, Harthun, & Valdez, 2011), and used a CBPR model of cultural adaptation similar to the adaptation of L2W (Kulis & Dustman, 2013). P2W is currently engaged in multiple phases of adaptation, validation, and pilot testing in preparation for a randomized controlled trial in collaboration with urban American Indian communities in Arizona. The goal is to ensure accurate representation of cultural constructs within the adapted curriculum. Through these processes, language, concepts, and learning style approaches that are common within universal parent training curricula have been changed to reflect the distinctive worldviews of American Indian families and their approaches to raising children. For example, rather than focusing on techniques for “disciplining” children consistently, P2W discusses ways of providing parental “guidance” for children. In addition, P2W was restructured to reflect a circular rather than linear approach to learning, starting each workshop lesson with a holistic concept rooted within traditional Native culture and moving to discuss its parts, rather than a part-to-whole learning style (Deschine et al., 2013). Overall, deep-structure cultural adaptations are most likely to address the core cultural components of prevention, because they rely heavily on the community as “experts” and collaborators in the adaptational process. Thus, in many ways, these types of adaptations are aligned more closely with culturally grounded approaches to prevention development.

Culturally Grounded Prevention

Culturally grounded approaches to developing drug prevention interventions utilize methods that place the culture and social context of the targeted population at the center of the intervention. Methods are used in which curricular components evolve from the “ground up” (i.e., from the worldviews, values, beliefs, and behaviors of the population that the program is intended to serve) and therefore look and sound familiar to the participants (Marsiglia & Kulis, 2009). Rigorously evaluated, culturally grounded prevention programs have been developed over the past decade, such as keepin’ it REAL (Hecht et al., 2003; Kulis et al., 2005; Marsiglia et al., 2005), which focuses on multicultural youth in the Southwestern U.S. (including Mexican Americans, European Americans and African Americans), and the Strong African American Families Program (SAAF; Brody, Murry, Chen, Kogan, & Brown, 2006; Brody, Murry, Gerrard, et al., 2006), which focuses on African American youth in the Southern U.S. While these programs are based on scientifically supported prevention components (e.g., resistance skills training), the specific content and delivery of these components evolved from CBPR practices (Gosin, Dustman, Drapeau, & Harthun, 2003). Community driven, culturally grounded prevention curricula have also been recently described, in which the research methods to create and validate the programs develop organically from the targeted population. For example, Puni Ke Ola is a unique photovoice project which is intended to develop drug prevention curricular components from Native Hawaiian methods and constructs (e.g., ‘āina; Helm, Lee, & Hanakahi, 2013). ‘Āina-based, or land-based, programs have been described as a unique core cultural component in social/behavioral interventions for Native Hawaiians (Morelli & Mateira, 2010). Components of the Puni Ke Ola curriculum emerge from interviews with rural Native Hawaiian youth based on their detailed interpretations of photos taken by them in their community.

Compared with culturally adapted approaches, culturally grounded approaches pose unique challenges related to evaluation and replication of interventions resulting from the process, as the process assumes that researchers and program developers have the unique skills and background to translate culture norms and values into developmentally appropriate prevention interventions. Culturally grounded interventions often evolve from researchers’ or developers’ in-depth, insider knowledge of specific cultural groups, making program replication and evaluation difficult for those less familiar with those cultural groups. Further, culturally grounded approaches require the most resources to develop and evaluate. For example, curricular components of the Ho’ouna Pono drug prevention curriculum created for rural Hawaiian youth took approximately six years to develop and validate, and have only recently been pilot tested (Helm & Okamoto, 2013). Further, these approaches require the highest level of engagement with the community, as youth and adult stakeholders contribute to the program at both the pre-prevention and translational phases of program development (Okamoto et al., 2006, 2012). While the time and cost investments are high, they may be necessary for unique populations in which available evidence-based practices have limited applicability or generalizability. For example, the prevention effects of the keepin’ it REAL drug prevention curriculum, which is an evidence-based curriculum evaluated with a predominantly Mexican/Mexican American youth sample in the Southwest U.S. (Hecht et al., 2003), was found to be generalizable to other ethnocultural groups in the region except for American Indian youth (Dixon et al., 2007). Based in part on these findings, Okamoto et al. (2012) have recently argued for the use of a culturally grounded approach to the development of prevention programs for indigenous youth populations (e.g., American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian youth), due to the inability of currently available empirically supported prevention interventions to effectively address the unique cultural constructs and contexts related to health disparities for these populations. Due to the lack of evidence-based, culturally grounded prevention interventions for these populations, Okamoto and colleagues further argued that more culturally grounded prevention interventions are needed, in order to develop the foundation for an indigenous prevention science that could serve as the starting point for adaptations for these youth.

Specifically, culturally grounded approaches may be most indicated for populations in which there is a high need for interventions within the community, a lack of prevention science to guide the adaptation of an intervention, and a potentially high overall scientific and health impact that could result from the culturally grounded effort. For example, the development of the Ho’ouna Pono drug prevention curriculum (Helm & Okamoto, 2013) was based on the disproportionately high rates of substance use for Native Hawaiian youth compared with other youth ethnic groups in Hawai’i, and evolved out of a lack of drug prevention research for Hawaiian youth (Edwards et al., 2010). The curriculum addresses the health needs of three underserved and intersecting populations in Hawai’i—indigenous youth (i.e., youth whose ancestors were native to the area comprising the State of Hawai’i prior to 1778), Pacific Islander youth (i.e., youth whose ethnocultural background originated among the islands in the Pacific region), and rural youth. Therefore, the impact of the curriculum is based on its potential to anchor future adaptations for these broader groups, in addition to addressing the substance use of the specific targeted population.

Overall, culturally grounded approaches are particularly innovative, because they situate evidence-based practices within a health disparities framework. Rather than adapting prevention curricular components from one population to another, they build the evidence base within the communities and cultures that are intended to be served. School-based, culturally grounded prevention curricula, in particular, are consistent with models of multicultural education, which have emphasized cultural and ethnic identification as a part of contemporary citizen education (Banks, 2012). Culturally grounded prevention interventions also tap into youths’ funds of knowledge (i.e., historically accumulated and culturally developed bodies of knowledge and skills), which are used as the foundation and context for delivering prevention curricula within specific communities of color (González & Moll, 2002; Moll, Amanti, Neff, & González, 1992). Ultimately, delivering prevention curricular content within youths’ funds of knowledge ensures that the core prevention components of the program address the social and cultural validity of the targeted population.

Discussion

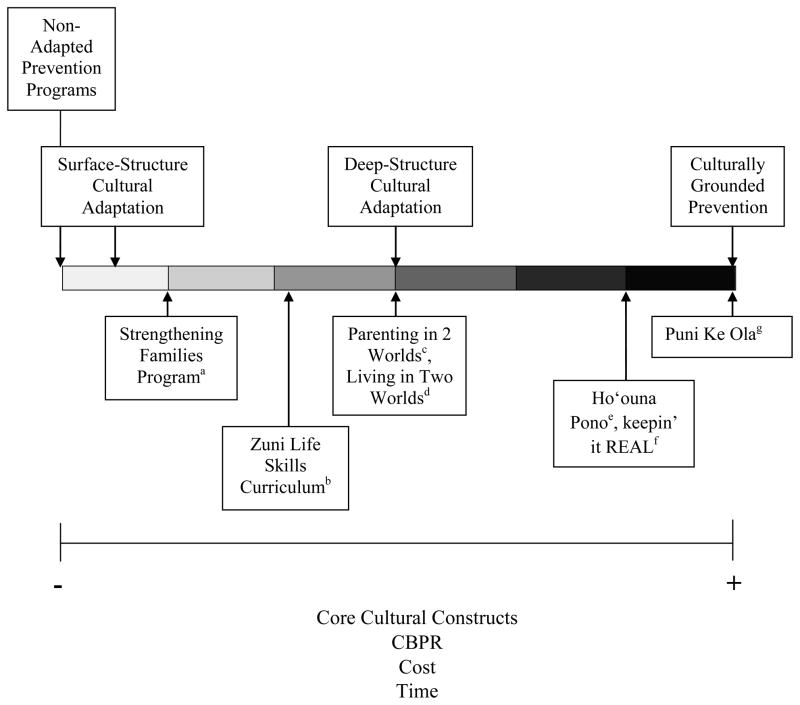

This article describes different approaches toward developing culturally focused interventions. These approaches range from non-adapted or surface-structure adapted programs to culturally grounded programs. Figure 1 describes these approaches on a continuum and maps examples of programs briefly described in this article across this continuum. Further, the figure also highlights how cost, time, engagement and collaboration with the community in the prevention developmental process (CBPR), and the ability to reflect core cultural constructs, vary based on the preventive approach. The relevance of this conceptual model is two-fold. First, it helps to clarify the variability in the use of the term “cultural adaptation” in prevention science. Currently, this term has been used to refer to a wide spectrum of principles and practices in health disparities and prevention science (Sims et al., 2013). The conceptual model differentiates between surface-structure adaptations, which are more similar to non-adapted approaches, and deep-structure adaptations, which are more similar to culturally grounded approaches. Second, the model helps to identify and define culturally grounded prevention within the context of cultural adaptations. While culturally grounded prevention interventions are not as widely recognized and have not been described in the literature as often as culturally adapted approaches, they have been developed and evaluated over the past decade in prevention research. Overall, this conceptual model provides a way for preventionists to refer to culturally focused programs along a continuum of different developmental prevention practices that have been used to create them.

Figure 1.

A Continuum of Approaches Toward Developing Culturally Focused Interventions

Note: CBPR = Community-Based Participatory Research

aKumpfer et al., 2002, 2008; bLaFromboise & Howard-Pitney, 1995; cDeschine et al., 2013; dJumper-Reeves et al., 2013; eHelm & Okamoto, 2013; fHecht et al., 2013; gHelm, Lee, & Hanakahi, 2013

Implications for Practice

The continuum of approaches to creating culturally focused prevention programs has implications for funding of the development of these programs, and for the nature of collaborations with communities in their creation. Recently, federal budgets for health research have been severely cut, requiring funding agencies to make investments in studies that reflect their specific missions more directly (Sims & Crump, 2013). As a result, these agencies are increasingly expected to consider the cost and time to conduct programs of research alongside their potential scientific impact. The conceptual model provides a means to address both of these issues. As proposed prevention studies become more culturally grounded in nature, they require more resources, but also address core cultural constructs more directly. Prevention researchers who conduct deep-structure or culturally grounded intervention research should subsequently identify the scientific and community-based need to address core cultural constructs for their specific target populations, in order to justify the investment required to develop these types of programs. Notable, however, is that innovative prevention practices that make important contributions to prevention science often emerge from culturally grounded approaches. These approaches provide a means toward situating prevention practices within a unique culture, region, and context, which in turn may function as a template for adaptations to populations within similar cultures, regions, and/or contexts (Okamoto et al., 2012).

Our conceptual model also provides a way in which to describe the commitment of the community in the development of the program, and the potential outcomes of their efforts. In some communities, particularly those with indigenous populations, there is an expectation of more intensive collaboration between researchers and the community in the development of a curriculum (Harthun, Dustman, Reeves, Marsiglia, & Hecht, 2009; Okamoto et al., 2006), which aligns more with deep-structure adaptations or culturally grounded approaches. In other communities, expectations for community involvement or collaboration may be lower, which suggests the use of non-adapted or surface-structure adapted approaches. The model allows for a description of the types of programs that could result from different levels of researcher and community collaborative efforts. Further, for researchers in partnership with communities, the model could also be used to describe multiple phases in the development of culturally focused interventions. As an example, a non-adapted version of an existing efficacious intervention could be implemented in order to gauge the nature and extent to which cultural adaptation is necessary for a given cultural group or population. The conceptual model presented in this paper could be used after the preliminary implementation and evaluation of the non-adapted version of the curriculum, in order to determine whether surface- or deep-structure adaptations or culturally grounded approaches are indicated.

Conclusions

Resnicow et al. (2000) originally defined the terms “deep structure” and “surface structure” in the context of cultural adaptations of interventions, while Okamoto et al. (2012) more recently described culturally “adapted” versus “grounded” approaches. While conceptually useful, dichotomizing these concepts may be misleading and over simplistic in that they suggest that the developers of prevention programs have used (or should use) one method or another. This article extends these initial definitions by encompassing programs evolving from efforts to achieve deep and surface structure and those using culturally grounded methods within a comprehensive conceptual model. The model described in this article includes programs using these different methods along a continuum, which has implications for funding as well as collaboration with communities in developing programs. The model provides a more accurate description of current efforts toward developing culturally focused prevention interventions, allowing preventionists and researchers to more accurately identify the process used to develop their interventions, and the type of content reflected in their curricula. Future research could use these categorizations to describe and examine which of these types of approaches toward prevention intervention development should be used, and under what circumstances, in order to justify the use of these different approaches. Future research specific to deep-structure and culturally grounded approaches might examine the developmental process in creating these interventions more closely. Specifically, this research might clarify who in the community should participate in the development of the prevention interventions, the impact that the development of the interventions has on community members (both the targeted population and community stakeholders), and how the cultural background of the developers and researchers influence the content and delivery of the intervention.

Acknowledgments

Resources used for preparation of this article were funded by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Drug Abuse (R34 DA031306, P.I.-Okamoto) and the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (R01 MD006110, P.I.-Kulis, and P20 MD002316, P.I.-Marsiglia). The authors would like to acknowledge Ms. Jessica Valdez and Ms. Michela Lauricella for their assistance in preparing this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Scott K. Okamoto, Hawai’i Pacific University

Stephen Kulis, Arizona State University

Flavio F. Marsiglia, Arizona State University

Lori K. Holleran Steiker, University of Texas at Austin

Patricia Dustman, Arizona State University

References

- Banks JA. Ethnic studies, citizenship education, and the public good. Intercultural Education. 2012;23(6):467–473. [Google Scholar]

- Botvin GJ, Schinke SP, Epstein JA, Diaz T. Effectiveness of culturally focused and generic skills training approaches to alcohol and drug abuse prevention among minority youths. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1994;8(2):116–127. [Google Scholar]

- Botvin GJ, Schinke SP, Epstein JA, Diaz T, Botvin EM. Effectiveness of culturally focused and generic skills training approaches to alcohol and drug abuse prevention among minority adolescents: Two-year follow-up results. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1995;9(3):183–194. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Murry VM, Chen Y, Kogan SM, Brown AC. Effects of family risk factors on dosage and efficacy of a family-centered preventive intervention for rural African Americans. Prevention Science. 2006;7:281–291. doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0032-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Murry VM, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, McNair L, Brown AC, et al. The Strong African American Families Program: Prevention of youths’ high-risk behavior and a test of a model for change. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20(1):1–11. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Barrera M, Holleran Steiker LK. Issues and challenges in the design of culturally adapted evidence-based interventions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2010;6:213–239. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-033109-132032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Barrera M, Martinez CR. The cultural adaptation of prevention interventions: Resolving tensions between fidelity and fit. Prevention Science. 2004;5:41–45. doi: 10.1023/b:prev.0000013980.12412.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschine NA, Harthun M, Denetsosie SM, Lewis SJ, Wolfersteig WL, Hibbler PK, et al. Cultural program adaptation to address “deep structure”: The Parenting in 2 Worlds Project for urban American Indian families. Paper presented at the the 21st Annual Meeting of the Society for Prevention Research; San Francisco, CA. 2013. May, [Google Scholar]

- Dixon A, Yabiku S, Okamoto SK, Tann SS, Marsiglia FF, Kulis S, et al. The effects of a multicultural school-based drug prevention curriculum with American-Indian youth in the Southwest U.S. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2007;28(6):547–568. doi: 10.1007/s10935-007-0114-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dustman P, Kulis SS. Reaching an invisible native population: Implementing a culturally adapted curriculum in urban schools. In: Okamoto S Chair, editor. Innovations in prevention interventions with indigenous youth and families; Symposium conducted at the 21st Annual Meeting of the Society for Prevention Research; San Francisco, CA. 2013. May, [Google Scholar]

- Edwards C, Giroux D, Okamoto SK. A review of the literature on Native Hawaiian youth and drug use: Implications for research and practice. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2010;9(3):153–172. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2010.500580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang L, Schinke SP. Two-year outcomes of a randomized, family-based substance use prevention trial for Asian American adolescent girls. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27(3):788–798. doi: 10.1037/a0030925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González N, Moll LC. Cruzando el Puente: Building bridges to funds of knowledge. Educational Policy. 2002;16(4):623–641. [Google Scholar]

- Gosin MN, Dustman PA, Drapeau AE, Harthun ML. Participatory action research: Creating an effective prevention curriculum for adolescents in the Southwest. Health Education Research: Theory and Practice. 2003;18(3):363–379. doi: 10.1093/her/cyf026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harthun M, Dustman P, Reeves L, Marsiglia FF, Hecht ML. Using community-based participatory research to adapt keepin’ it REAL: Creating a socially, developmental, and academically appropriate prevention curriculum for 5th graders. Journal of Alcohol & Drug Education. 2009;53:12–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht ML, Marsiglia FF, Elek E, Wagstaff DA, Kulis S, Dustman P. Culturally-grounded substance use prevention: An evaluation of the keepin’ it REAL curriculum. Prevention Science. 2003;4:233–248. doi: 10.1023/a:1026016131401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helm S, Lee W, Hanakahi V. Puni Ke Ola pilot project. In: Okamoto S Chair, editor. Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander (NHOPI) substance abuse prevention interventions; Symposium conducted at the 21st Annual Meeting of the Society for Prevention Research; San Francisco, CA. 2013. May, [Google Scholar]

- Helm S, Okamoto SK. Developing the Ho’ouna Pono Substance Use Prevention Curriculum: Collaborating with Hawaiian youth and communities. Hawai’i Journal of Medicine and Public Health. 2013;72(2):66–69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holleran Steiker LK, Castro FG, Kumpfer K, Marsiglia FF, Coard S, Hopson LM. A dialogue regarding cultural adaptation of interventions. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions. 2008;8(1):154–162. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang WC. The formative method for adapting psychotherapy (FMAP): A community-based developmental approach to culturally adapting therapy. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2009;40(4):369–377. doi: 10.1037/a0016240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jumper-Reeves L, Dustman PA, Harthun ML, Kulis S, Brown EF. American Indian cultures: How CBPR illuminated intertribal cultural elements fundamental to an adaptation effort. Prevention Science. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s11121-012-0361-7. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulis SS, Dustman P. The Parenting in 2 Worlds Project: CBPR with urban American Indian families. In: Okamoto S Chair, editor. Innovations in prevention interventions with indigenous youth and families; Symposium conducted at the 21st Annual Meeting of the Society for Prevention Research; San Francisco, CA. 2013. May, [Google Scholar]

- Kulis S, Dustman PA, Brown EF, Martinez M. Expanding urban American Indian youths’ repertoire of drug resistance skills: Pilot results from a culturally adapted prevention program. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research. 2013;20(1):35–54. doi: 10.5820/aian.2001.2013.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulis S, Marsiglia FF, Elek E, Dustman P, Wagstaff DA, Hecht ML. Mexican/Mexican American adolescents and keepin’ it REAL: An evidence-based substance use prevention program. Children and Schools. 2005;27(3):133–145. doi: 10.1093/cs/27.3.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumpfer KL, Alvarado R, Smith P, Bellamy N. Cultural sensitivity in universal family-based prevention interventions. Prevention Science. 2002;3(3):241–244. doi: 10.1023/a:1019902902119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumpfer KL, Pinyuchon M, de Melo AT, Whiteside HO. Cultural adaptation process for international dissemination of the Strengthening Families Program. Evaluation & the Health Professions. 2008;31(2):226–239. doi: 10.1177/0163278708315926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFromboise T, Howard-Pitney B. The Zuni Life Skills Development Curriculum: Description and evaluation of a suicide prevention program. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1995;42(4):479–486. [Google Scholar]

- LaFromboise T, Lewis HA. The Zuni Life Skills Development Program: A school/community-based suicide prevention intervention. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2008;38(3):343–353. doi: 10.1521/suli.2008.38.3.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau AS. Making the case for selective and directed cultural adaptations of evidence-based treatments: Examples from parent training. Clinical Psychology: Research and Practice. 2006;13:295–310. [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Kulis S. Diversity, oppression, and change: Culturally grounded social work. Chicago, IL: Lyceum Books; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Kulis S, Wagstaff D, Elek E, Dran D. Acculturation status and substance use prevention with Mexican and Mexican-American youth. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions. 2005;5(½):85–111. doi: 10.1300/J160v5n01_05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKleroy VS, Galbraith JS, Cummings B, Jones P, Harshbarger C, Collins C, et al. Adapting evidence-based behavioral interventions for new settings and target populations. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2006;18(suppl A):59–73. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.supp.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll LC, Amanti C, Neff D, González N. Fund of knowledge for teaching: Using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms. Theory into Practice. 1992;31(2):132–141. [Google Scholar]

- Morelli PT, Mataira PJ. Indigenizing evaluation research: A long-awaited paradigm shift. Journal of Indigenous Voices in Social Work. 2010;1(2):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto SK, Helm S, Pel S, McClain LL, Hill AP, Hayashida JKP. Developing empirically based, culturally grounded drug prevention interventions for indigenous youth populations. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s11414-012-9304-0. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto SK, LeCroy CW, Tann SS, Dixon Rayle A, Kulis S, Dustman P, et al. The implications of ecologically based assessment for primary prevention with Indigenous youth populations. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2006;27(2):155–170. doi: 10.1007/s10935-005-0016-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsai MB, Castro FG, Marsiglia FF, Harthun ML, Valdez H. Using community based participatory research to create a culturally grounded intervention for parents and youth to prevent risky behaviors. Prevention Science. 2011;12:34–47. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0188-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnicow K, Soler R, Braithwaite R, Ahluwalia J, Butler J. Cultural sensitivity in substance use prevention. Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28:271–290. [Google Scholar]

- Ringwalt C, Bliss K. The cultural tailoring of a substance use prevention curriculum for American Indian youth. Journal of Drug Education. 2006;36:159–177. doi: 10.2190/369L-9JJ9-81FG-VUGV. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims B, Beltangady M, Gonzalez NA, Whitesell N, Castro FG. The role of cultural adaptation in dissemination and implementation science. Roundtable conducted at the 21st Annual Meeting of the Society for Prevention Research; San Francisco, CA. 2013. May, [Google Scholar]

- Sims B, Crump AD. Your federal grant application-practical considerations for lean times. Roundtable conducted at the 21st Annual Meeting of the Society for Prevention Research; San Francisco, CA. 2013. May, [Google Scholar]