Abstract

Objective

To identify baseline attributes associated with consecutively missed data collection visits during the first 48 months of Look AHEAD—a randomized, controlled trial in 5145 overweight/obese adults with type 2 diabetes designed to determine the long-term health benefits of weight loss achieved by lifestyle change.

Design and Methods

The analyzed sample consisted of 5016 participants who were alive at month 48 and enrolled at Look AHEAD sites. Demographic, baseline behavior, psychosocial factors, and treatment randomization were included as predictors of missed consecutive visits in proportional hazard models.

Results

In multivariate Cox proportional hazard models, baseline attributes of participants who missed consecutive visits (n=222) included: younger age ( Hazard Ratio [HR] 1.18 per 5 years younger; 95% Confidence Interval 1.05, 1.30), higher depression score (HR 1.04; 1.01, 1.06), non-married status (HR 1.37; 1.04, 1.82), never self-weighing prior to enrollment (HR 2.01; 1.25, 3.23), and randomization to minimal vs. intensive lifestyle intervention (HR 1.46; 1.11, 1.91).

Conclusions

Younger age, symptoms of depression, non-married status, never self-weighing, and randomization to minimal intervention were associated with a higher likelihood of missing consecutive data collection visits, even in a high-retention trial like Look AHEAD. Whether modifications to screening or retention efforts targeted to these attributes might enhance long-term retention in behavioral trials requires further investigation.

Keywords: randomized clinical trials, behavioral trial, retention, obesity

Participant retention is a major challenge in long-term randomized controlled trials of behavioral lifestyle interventions.1 There is evidence that attrition in randomized behavioral weight-loss studies is associated with treatment-related factors including random assignment to the ‘control’ group 2 and dissatisfying weight loss outcomes early in the intervention.3 Moreover, there may be behavioral and psychosocial factors at baseline that are overlooked during screening or enrollment, but predict poor retention. Previous studies indicate that number of weight loss attempts, poorer quality of life, mental illness, lack of exercise, and lack of self-efficacy to increase physical activity at pretreatment are associated with attrition.4,5

Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) is a 16-center randomized clinical trial of an intensive weight loss intervention for overweight and obese adults with type 2 diabetes.6 The main purpose of Look AHEAD is to examine the long-term effects of weight loss on incidence of major cardiovascular events.6 Participants were enrolled from 2001 to 2004, and one-year7 and four-year 8 results have been published. Participant follow-up rates have been 93% or greater each year between year one and year four.7,8 Thus, Look AHEAD presents a unique opportunity to examine predictors of missed follow-up visits in a large-scale, long-term randomized clinical trial of a lifestyle intervention.

We analyzed data from the first 48 months of Look AHEAD to identify behavioral and psychosocial factors at baseline that predict missing two consecutive 6-month data collection visits (defined in the study as ‘inactive status’).

Methods

Details regarding recruitment, eligibility criteria, randomization, and data collection have been reported elsewhere.6-9 In summary, 5145 adults were recruited from 16 centers across the United States. Eligible participants were between ages 45-76, diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, and had a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25 kg/m2 (BMI ≥ 27 kg/m2 if taking insulin). Each participant underwent a standardized interview to obtain information on employment, education, smoking, and alcohol use. Race/ethnicity was self-reported using questions from the 2000 U.S. Census questionnaire. Participants also completed several assessments at baseline regarding their eating patterns, physical activity, use of resources, weight control practices, binge eating, weight loss history, symptoms of depression, and health related quality of life. Items for these assessments were developed by the Look AHEAD research team, with the exception of measures of quality of life (SF-36),10 symptoms of depression (Beck Depression Inventory),11 and physical activity (Paffenbarger scale).12

Randomization and Intervention

After screening and baseline visits, participants within each center were randomized to either the Diabetes Support and Education (DSE; control condition) or Intensive Lifestyle Intervention (ILI) condition. Details about the intervention design have been reported previously.13 In summary, the DSE intervention consisted of three group sessions per year focused on diet, physical activity, and social support. ILI included dietary counseling and physical activity sessions in both individual and group formats. The ILI goal was an average weight loss of 7% at year one and maintenance in the following years. We adjusted for treatment randomization in the analysis as a predictor of missing two consecutive 6-month visits.

Measures

For this current analysis, we were particularly interested in potential baseline behavioral and psychosocial as well as demographic predictors of missing two consecutive 6-month visits during the first 48 months of Look AHEAD. Selection of variables to include in the analysis was exploratory (see descriptions below) and consisted of variables found to be significant predictors of attrition in previous studies and variables that had not previously been examined, but that represented behavioral attributes we thought may be associated with missing data collection visits.

Eating Patterns

Aspects of dietary intake have been associated with attrition in a previous clinical trial.5 Therefore, we included two dietary items as predictors in the analysis: 1) number of times the participant ate per day; and 2) how many times per week the participant ate fast food. These items were administered as part of the Eating Patterns questionnaire14 at baseline. .

Physical Activity

Engagement, or the lack thereof, in physical activity has also been associated with poor retention.5 Self-reported physical activity data was collected using two separate measures: 1) the Paffenbarger scale12 to assess leisure time physical activity (LTPA); and 2) a single item measure that asked participants to provide the number of days per week they engaged in activities long enough to work up a sweat (i.e., “sweat episodes”). LTPA level and number of ‘sweat episodes’ at baseline were assessed on approximately 50% of Look AHEAD participants.15 Standardized scoring procedures were used to compute total energy expenditure (kcal*wk−1) of LTPA from the Paffenbarger scale.12

Use of Resources

Lack of self-efficacy to increase physical activity was a significant predictor of attrition in a recent trial of a weight loss intervention for individuals at high risk for type 2 diabetes.4 Self-efficacy was not formally assessed at baseline in Look AHEAD; however, participants were asked to rate their feelings about physical activity (i.e., enjoy, neutral, or dislike exercise). This item was included as a predictor in the analyses. In addition to having the confidence, level of social support for and time spent engaging in healthy behaviors may also be participant attributes associated with trial retention. We included the following two items from the Use of Resources questionnaire (total of 12 items) as predictors: 1) number of hours per week family and friends spent exercising with the participant; and 2) number of hours the participant spends shopping and preparing food for him or herself.

Weight Control Practices and Weight Loss History

Although there is support for the association between number of weight loss attempts and study attrition,5 other aspects of weight management history still need to be explored. Weight control practices prior to enrollment were assessed using a self-report measure developed for the Look AHEAD Study.14 The measure consists of items that address questions related to self-weighing, attempts to lose weight, and diet- and physical activity- related behaviors in the past year, including self-monitoring. For the item assessing frequency of self-weighing, we combined the two responses ‘weighing everyday’ and ‘weighing more than once a day’ due to low frequency of endorsement of the latter; thus, there were six possible response options for this item (see Table 1). We also included the following items in the analyses regarding weight control practices: 1) ever tried to lose weight (yes/no); 2) ever participated in a weight loss program (yes/no); 3) ate a low calorie diet in the past year (yes/no); 4) reduced calories consumed in the past year (yes/no); 5) recorded food intake daily in the past year (yes/no); 6) used meal replacements in the past year (yes/no); and 7) used diet pills in the past year (yes/no). For weight loss history,14 we included the item, ‘how many times have you lost 20 lbs on purpose since the age of 20 years old.’ Response categories for this item is on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0, 1-2, 3-4, 5-6, and 7+ times.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics by Missed Visit Status (N = 5016)

| No Consecutive Missed Visits (n = 4794) | Two Consecutive Missed Visits (n = 222) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Treatment, % | .028 | ||

| DSE | 50 | 57 | |

| ILI | 50 | 43 | |

| Age (years), M(SD) | 58.75 (6.84) | 57.21 (6.56) | < .001 |

| Race, % | < .001 | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 64 | 59 | |

| African American | 16 | 21 | |

| Hispanic | 12 | 18 | |

| Native American plus | 8 | 2 | |

| Other/Mixed | |||

| Sex, % | .418 | ||

| Men | 40 | 43 | |

| Women | 60 | 57 | |

| Education, % | .369 | ||

| < 13 years | 20 | 19 | |

| 13-16 years | 38 | 43 | |

| > 16 years | 42 | 39 | |

| Employment, % | .412 | ||

| Employed | 71 | 74 | |

| Unemployed | 29 | 26 | |

| Marital Status, % | < .001 | ||

| Married | 69 | 58 | |

| Not Married | 31 | 42 | |

| Body Mass Index kg/m2, M(SD) | 35.96 (5.92) | 35.93 (5.61) | .938 |

| Substance Use | |||

| Current Smoker, % | .345 | ||

| Yes | 9 | 7 | |

| No | 91 | 94 | |

| No. of beers/week, M(SD) | .69 (2.31) | .77 (1.72) | .593 |

| No. of hard drinks/week, M(SD) | .57 (1.74) | .53 (1.65) | .812 |

| No. of glasses of wine/week, M(SD) | .98 (2.11) | .83 (1.78) | .348 |

| Mental Health | |||

| Binge Eating, % | .081 | ||

| Yes | 13 | 17 | |

| No | 87 | 83 | |

| Beck Depression Score, M(SD) | 5.39 (4.82) | 6.76 (6.26) | .002 |

| SF-36 Physical Function, M(SD) | 49.11 (7.56) | 48.76 (7.97) | .518 |

| SF-36 Role Physical, M(SD) | 50.41 (7.93) | 49.79 (8.37) | .286 |

| SF-36 General Health, M(SD) | 47.28 (8.85) | 45.93 (9.42) | .037 |

| SF-36 Role Emotional, M(SD) | 51.84 (7.42) | 50.62 (8.34) | .034 |

| SF-36 Mental Health, M(SD) | 53.82 (7.82) | 52.47 (8.88) | .028 |

| Weight Loss Practices & History | |||

| Ever tried to lose weight, % | .258 | ||

| Yes | 94 | 96 | |

| No | 6 | 4 | |

| Ever participated in weight loss program, % | .566 | ||

| Yes | 54 | 52 | |

| No | 46 | 48 | |

| Self-weighing in past year, % | .019 | ||

| Never | 7 | 13 | |

| Once a year | 6 | 8 | |

| Every couple months | 27 | 27 | |

| Every month | 17 | 19 | |

| Every week | 30 | 22 | |

| Every day or more than once a day | 13 | 11 | |

| Weight loss group in past year, % | .601 | ||

| Yes | 12 | 13 | |

| No | 88 | 87 | |

| Meal replacement in past year, % | .685 | ||

| Yes | 16 | 15 | |

| No | 84 | 85 | |

| Take diet pills in past year, % | .867 | ||

| Yes | 4 | 5 | |

| No | 96 | 95 | |

| Keep graph of weight in past year, % | .589 | ||

| Yes | 7 | 8 | |

| No | 93 | 92 | |

| Number of times lost 20-49lbs, % | .978 | ||

| 0 | 47 | 46 | |

| 1-2 | 37 | 37 | |

| 3-4 | 10 | 11 | |

| 5-6 | 3 | 3 | |

| 7+ | 3 | 3 | |

| Dietary Behaviors | |||

| No. of days/week eat fast food, M(SD) | 1.84 (2.62) | 2.38 (3.47) | .025 |

| No. of hours/week shopping and preparing food for yourself, M(SD) | 6.60 (5.86) | 5.96 (5.01) | .085 |

| No. of hours/week family shopping and preparing food for you, M(SD) | 5.32 (5.53) | 5.56 (5.35) | .623 |

| No. of times eat per day, M(SD) | 4.94 (2.92) | 5.51 (4.96) | .091 |

| Record intake daily past year, M(SD) | .126 | ||

| Yes | 38 | 33 | |

| No | 62 | 67 | |

| Low calorie diet in past year, M(SD) | .361 | ||

| Yes | 18 | 20 | |

| No | 82 | 80 | |

| Reduce calories in past year, M(SD) | .958 | ||

| Yes | 52 | 52 | |

| No | 48 | 48 | |

| Exercise Behaviors | |||

| Feelings about Exercise, M(SD) | .039 | ||

| Enjoy exercise | 66 | 58 | |

| Neutral | 26 | 31 | |

| Dislike exercise | 7 | 10 | |

| Paffenbarger Score, M(SD) | 874.9 (1162.3) | 711.1 (951.0) | .089 |

| No. of times/week engage in sweat exercise, M(SD) | 1.73 (2.21) | 1.44 (2.16) | .178 |

| No. of hours/week family spends exercising with you, M(SD) | 2.72 (3.68) | 2.06 (1.80) | .008 |

Note. Not married category includes single, separated, divorced, and widowed. DSE = Diabetes Support & Education; ILI = Intensive Lifestyle Intervention

Binge Eating

A previous weight loss study demonstrated that the presence of binge eating was associated with participant attrition.5 In Look AHEAD, binge eating was assessed using two items from the Questionnaire of Eating and Weight Patterns16: 1) Did you ever eat a really big amount of food within a short time (two hours or less) in the past six months; and 2) When you ate a really big amount of food, did you ever feel that you could not stop eating. If the participant responded ‘yes’ to both questions then he/she was classified as engaging in binge eating.

Depression and Health Related Quality of Life

Mental illness and quality of life have been established as predictors of attrition in previous studies.5,17-19 The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)11 was used to assess participants’ experience of depression symptoms at baseline. Quality of life was assessed using the SF-36,10 a widely used measure in clinical studies. For this current study, we examined the T scores for physical functioning, physical role functioning, general health, emotional role, and mental health subscales of the SF-36 as predictors.

Outcomes

The main outcome for the current study was whether or not a participant had missed two consecutive 6-month data collection visits, among participants who were not deceased. Data collection visits occurred every six months, alternating between phone and in-person follow-up. Missing two consecutive visits does not equate to study drop-out; however, participants were considered in an ‘inactive status’ in the trial. Although participants could have missed two consecutive data collection visits several times during the 48 months, we only examined time to first missing two consecutive visits.

Statistical Analysis

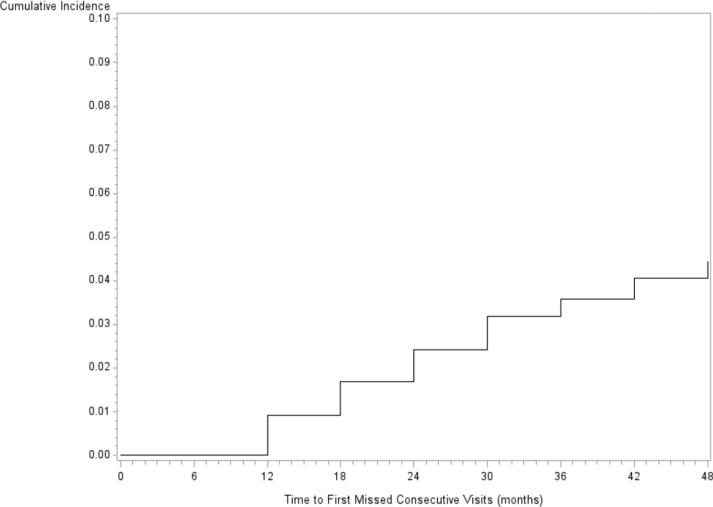

Descriptive statistics, proportional hazard models, and survival analysis were completed using SAS, version 9.2.20 Participants were excluded from analyses if they (a) had died or (b) were randomized at a clinical center which experienced changes in institutional home and the participant elected not to continue in the study after this change (pooled n=129). Therefore, the total sample included in the analyses was 5016 participants. Chi-square and t-tests were conducted to compare participants who missed two consecutive visits to those who did not on demographic, substance use, mental health, weight control practices, weight loss history, dietary behaviors, and physical activity (Table 1). Variables that differed significantly between the two groups, according to the chi-square and t-tests (p < .05), were included in the Cox proportional hazard models. We ran univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard models to obtain the hazard ratios for each predictor variable of time to first missing two consecutive data collection visits. Kaplan-Meier plot was constructed to examine the cumulative incident functions for time to first missing two consecutive 6-month data collection visits over the first 48 months of Look AHEAD. Participants who never missed two consecutive visits during the 48 months were censored at month 48. Statistical significance was defined as p < .05.

Results

There were 222 participants who missed two consecutive data collection visits (i.e., were classified as ‘inactive’) during the first 48 months of Look AHEAD, 66 of whom went on to withdraw during that time period. Figure 1 presents the unadjusted cumulative incidence plot for time to first missing two consecutive six-month visits. The plot increases in a step-wise function every six months, suggesting an event rate that was slow, but steady.

Figure 1.

Unadjusted Cumulative Incidence Function of Time to Missing Two Consecutive Visits during First 48 Months in Look AHEAD

Table 1 displays baseline sample characteristics for Look AHEAD participants by consecutive missed visit status. Based on chi-square and t-test analyses, the following baseline characteristics were significantly different between the groups and thus included in the univariate Cox proportional hazard models as predictors of missing two consecutive data collection visits: race/ethnicity; age, marital status; frequency of self-weighing (categorical); social support for exercise; Beck depression score; general health score on SF-36; emotional role score on SF-36; mental health score on SF-36; feelings about physical activity; frequency of fast food consumption per week; and treatment randomization.

Univariate Analysis

Table 2 presents the results of the univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard models. In the univariate analysis, participants randomized to the DSE condition were at 35% higher risk for missing two consecutive visits compared to ILI participants. Risk for missing two consecutive visits was higher for African American and Hispanic participants compared to non-Hispanic Whites. Given the small sample sizes of Native Americans, Alaskan Natives, American Indian, Asian/Pacific Islander, and Other or Mixed Race, we combined these participants into one group (n = 401). This combined group was at less risk for missing consecutive data collection visits compared to non-Hispanic Whites. Participants who were not married (i.e., divorced, never married, separated, or widowed) compared to married (also includes, participants who were ‘living in a marriage like relationship’), participants who disliked exercise compared to those who enjoyed exercise, and participants who never self-weighed compared to those who weighed weekly or more prior to study enrollment were at increased risk for missing two consecutive data collection visits during the first 48 months of the trial. Higher Beck depression score, higher consumption of fast food at baseline, and being of younger age were also associated with an increase in risk for missing two consecutive six-month data collection visits.

Table 2.

Proportional Hazard Models for Predicting Missed Visits in Look AHEAD Trial, First 48 Months

| Univariate model HR (95% CI) | Multivariate adjusted modelcHR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment Assignment | ||

| DSE | 1.35 (1.03, 1.76) | 1.46 (1.11, 1.91) |

| ILI | Reference | Reference |

| Race/ethnicitya | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | Reference | Reference |

| African American | 1.44 (1.03, 2.01) | 1.21 (.85, 1.74) |

| Hispanic | 1.60 (1.13, 2.27) | 1.41 (.98, 2.03) |

| Native Americans plus Others | .30 (.12, .74) | .58 (.22, 1.58) |

| Age (per 5 years) | 1.18 (1.06, 1.30) | 1.18 (1.05, 1.30) |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married | Reference | Reference |

| Not Married | 1.54 (1.18, 2.01) | 1.37 (1.04, 1.82) |

| Beck Depression Score | 1.05 (1.03, 1.07) | 1.04 (1.01, 1.06) |

| SF-36 General Healthb | .99 (.97, 1.01) | --- |

| SF-36 Emotional Roleb | .99 (.97, 1.01) | --- |

| SF-36 Mental Healthb | .98 (.97, 1.00) | --- |

| Feelings about exercise | ||

| Enjoy exercise | Reference | Reference |

| Neutral | 1.34 (.99, 1.79) | 1.27 (.94, 1.71) |

| Dislike exercise | 1.56 (1.02, 2.47) | 1.12 (.69, 1.81) |

| Number of hours/week family spends exercising with you | .90 (.80, 1.01) | --- |

| Number of days/week eat fast food | 1.06 (1.02, 1.11) | 1.03 (.99, 1.08) |

| Frequency of self-weighing | ||

| Never | 2.33 (1.47, 3.71) | 2.01 (1.25, 3.23) |

| Once a year | 1.62 (.93, 2.81) | 1.37 (.78, 2.40) |

| Every couple of months | 1.33 (.91, 1.93) | 1.21 (.82, 1.78) |

| Every month | 1.52 (1.00, 2.29) | 1.45 (.96, 2.20) |

| Every week | Reference | Reference |

| Everyday or more than once a day | 1.14 (.70, 1.86) | 1.21 (.74, 1.99) |

Dummy vectors for African Americans, Hispanics, and Native Americans plus Others compared to Non-Hispanic Whites were included in the same univariate model. Native American category includes Native Americans, Alaskan Natives, American Indian, Asian/Pacific Islander, and Other or Mixed Race.

SF-36 General Health, Emotional Role and Mental Health were included in the same univariate model.

Multivariate adjusted model included treatment assignment, race/ethnicity, age, marital status, depression score, frequency of fast food consumption, feelings about physical activity, and frequency of self-weighing.

Multivariate Analysis

The multivariate model included all the variables that were significant in the univariate analysis (i.e., treatment randomization, race/ethnicity, age, marital status, frequency of self-weighing, Beck depression score, feelings about physical activity, and number of days per week consumed fast food). Race/ethnicity, feelings about physical activity, and fast food consumption were no longer significant predictors of missing two consecutive visits in the multivariate model (Table 2). In the multivariate analysis, not being married (HR = 1.37; 95% CI 1.04, 1.82), never self-weighing prior to enrollment (HR = 2.01; 95% CI 1.25, 3.23), and randomization to DSE (HR = 1.46; 95% CI 1.11, 1.91) remained significant predictors for missing two consecutive data collection visits. Also, participants experiencing more symptoms of depression (HR = 1.04; 95% CI 1.01, 1.06) and of younger age (per 5 years; HR = 1.18; 95% CI 1.05, 1.30) were at increased risk for missing consecutive visits. There were no significant interactions between treatment randomization and the other predictor variables included in the model.

Discussion

We sought to identify baseline predictors of missing two consecutive six-month data collection visits in the Look AHEAD Study. Only 4.4% of participants missed two consecutive data collection visits at some point during the first 48 months of the trial, indicating successful retention efforts. Despite impressive retention, we identified demographic, psychosocial, and behavioral characteristics associated with missing consecutive visits. In a multivariate model adjusted for significant predictors from the univariate models, age, marital status, symptoms of depression, frequency of self-weighing, and treatment randomization remained significant, independent predictors of missing two consecutive data collection visits.

In many ways, our findings are similar to previous studies that have examined predictors of attrition within weight loss trials. Specifically, younger age has commonly been associated with participant drop-out.17,21,22 Furthermore, reporting more symptoms of depression at baseline5,17-19 as well as randomization to control or minimal intervention2 have consistently been shown to predict attrition. However, it should be noted that persons who had been hospitalized for depression within the last six months prior to baseline were excluded from the trial, so our estimates of the relationship between symptoms of depression and missing consecutive visits may be an underestimate. There is also previous support for our finding regarding marital status as a predictor.22

Our finding that never self-weighing prior to study enrollment as a predictor of poor retention is novel. Frequency of self-weighing, specifically never self-weighing, may be an indicator of lack of resources such as a scale, lack of concern about weight or overall health (i.e., lack of self-awareness), poor self-regulatory skills, and/or anxiety regarding getting on the scale and seeing one's weight. As a primary outcome measure, participants were weighed during the in-person follow-up visits. If never self-weighing prior to enrollment was due to lack of resources, then the larger issue may be low socioeconomic status, and the relationship between never self-weighing and missed consecutive visits may have been due to the individual not having the means (i.e., transportation or money for public transportation) to attend the visit. However, if participants expressed lack of transportation or money as reasons for not attending visits, transportation was arranged or home visits were conducted by the Look AHEAD study site. Another speculation is that never self-weighing prior to enrollment was perhaps a way to avoid or reduce the anxiety, depression, and/or low self-esteem individuals may experience before and after stepping on the scale. Perhaps to maintain this coping strategy, these participants missed follow-up visits in which they knew they had to get on the scale. Whereas participants who were already in the habit of weekly self-weighing were more comfortable with getting on the scale and thus were less likely to miss follow-up visits.

Several limitations of our analyses deserve mention. First, Look AHEAD achieved very high retention by using a variety of retention strategies, so our findings may not be applicable to trials with less successful retention efforts. Second, we used a proxy for drop-out (i.e., missing two consecutive visits) rather than actual withdrawal from the trial because the number of these events was small. Nonetheless, missing consecutive visits is a widely accepted indicator of high drop-out risk. Third, the baseline characteristics included in the models may be proxies for other variables/constructs not actually assessed during the trial. Finally, the results do not indicate causation, but rather an association between baseline characteristics and missing consecutive visits.

Despite these limitations, the study has several strengths. Look AHEAD, a long-term, behaviorally demanding, multicenter trial, maintained an over 90% retention rate during the first four years of the study. This high retention rate allowed us to examine potential predictors of high drop-out risk over 48 months using survival analysis in a large diverse sample. Study retention was a priority in Look AHEAD as there was a dedicated retention committee with representatives from each study site. Retention efforts included providing honorariums for completing study visits as well as regular mailings of postcards or informational letters to maintain contact with participants between visits. Furthermore, weekend data collection visits were made available to participants who were not available during the week at some study sites. However, the effectiveness of these efforts has yet to be examined.

Our findings that age, marital status, endorsing symptoms of depression, and frequency of self-weighing are associated with missed consecutive data collection visits in a long-term clinical trial begs the question of how individuals with these attributes should be treated in future trials. We don't believe it is appropriate for these attributes to be considered exclusion criteria, but instead individuals with these attributes may be specifically targeted for retention efforts if these efforts do not influence the main outcome of the study. For instance, retention efforts in future trials for younger adults may include weekend data collection visits or the use of technology to decrease the need for in-person contacts. Furthermore, providing pamphlets (control group) or early intervention sessions (treatment group) on stress, depression, coping, and building a healthy psychological relationship with the scale may improve retention of individuals who report depressive symptoms or failure to self-weigh at baseline. Although, we do not have enough evidence to expect that retention efforts that address these characteristics will indeed increase retention, additional qualitative and quantitative studies that address the mechanisms behind these associations with missed visits are warranted.

What is already known about this subject?

Retention in a long-term behavioral weight loss trial is challenging

Randomization to control group and mental illness are associated with poor retention

What does this study add?

Younger age, depression, and non-married status are independent predictors of high risk for drop-out

Failure to self-weigh prior to enrollment in a behavioral weight loss trial is associated with high risk for drop-out

Acknowledgements

This paper is in memory of our mentor, colleague, and friend, Dr. Frederick L. Brancati. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award U01DK057149.

Clinical Sites

The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions Frederick L. Brancati, MD, MHS1; Lee Swartz2; Lawrence Cheskin, MD3; Jeanne M. Clark, MD, MPH3; Kerry Stewart, EdD3; Richard Rubin, PhD3; Jean Arceci, RN; Suzanne Ball; Jeanne Charleston, RN; Danielle Diggins; Mia Johnson; Joyce Lambert; Kathy Michalski, RD; Dawn Jiggetts; Chanchai Sapun

Pennington Biomedical Research Center George A. Bray, MD1; Kristi Rau2; Allison Strate, RN2; Frank L. Greenway, MD3; Donna H. Ryan, MD3; Donald Williamson, PhD3; Brandi Armand, LPN; Jennifer Arceneaux; Amy Bachand, MA; Michelle Begnaud, LDN, RD, CDE; Betsy Berhard; Elizabeth Caderette; Barbara Cerniauskas, LDN, RD, CDE; David Creel, MA; Diane Crow; Crystal Duncan; Helen Guay, LDN, LPC, RD; Carolyn Johnson, Lisa Jones; Nancy Kora; Kelly LaFleur; Kim Landry; Missy Lingle; Jennifer Perault; Cindy Puckett; Mandy Shipp, RD; Marisa Smith; Elizabeth Tucker

The University of Alabama at Birmingham Cora E. Lewis, MD, MSPH1; Sheikilya Thomas MPH2; Monika Safford, MD3; Vicki DiLillo, PhD; Charlotte Bragg, MS, RD, LD; Amy Dobelstein; Stacey Gilbert, MPH; Stephen Glasser, MD3; Sara Hannum, MA; Anne Hubbell, MS; Jennifer Jones, MA; DeLavallade Lee; Ruth Luketic, MA, MBA, MPH; L. Christie Oden; Janet Raines, MS; Cathy Roche, PhD, RN; Janet Truman; Nita Webb, MA; Casey Azuero, MPH; Jane King, MLT; Andre Morgan

Harvard Center

Massachusetts General Hospital. David M. Nathan, MD1; Enrico Cagliero, MD3; Kathryn Hayward, MD3; Heather Turgeon, RN, BS, CDE2; Linda Delahanty, MS, RD3; Ellen Anderson, MS, RD3; Laurie Bissett, MS, RD; Valerie Goldman, MS, RD; Virginia Harlan, MSW; Theresa Michel, DPT, DSc, CCS; Mary Larkin, RN; Christine Stevens, RN; Kylee Miller, BA; Jimmy Chen, BA; Karen Blumenthal, BA; Gail Winning, BA; Rita Tsay, RD; Helen Cyr, RD; Maria Pinto

Joslin Diabetes Center: Edward S. Horton, MD1; Sharon D. Jackson, MS, RD, CDE2; Osama Hamdy, MD, PhD3; A. Enrique Caballero, MD3; Sarah Bain, BS; Elizabeth Bovaird, BSN, RN; Barbara Fargnoli, MS,RD; Jeanne Spellman, BS, RD; Ann Goebel-Fabbri, PhD; Lori Lambert, MS, RD; Sarah Ledbury, MEd, RD; Maureen Malloy, BS; Kerry Ovalle, MS, RCEP, CDE

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center: George Blackburn, MD, PhD1; Christos Mantzoros, MD, DSc3; Ann McNamara, RN; Kristina Spellman, RD

University of Colorado Health Sciences Center James O. Hill, PhD1; Marsha Miller, MS, RD2; Brent Van Dorsten, PhD3; Judith Regensteiner, PhD3; Ligia Coelho, BS; Paulette Cohrs, RN, BSN; Susan Green; April Hamilton, BS, CCRC; Jere Hamilton, BA; Eugene Leshchinskiy; Lindsey Munkwitz, BS; Loretta Rome, TRS; Terra Worley, BA; Kirstie Craul, RD,CDE; Sheila Smith, BS

Baylor College of Medicine John P. Foreyt, PhD1; Rebecca S. Reeves, DrPH, RD2; Henry Pownall, PhD3; Ashok Balasubramanyam, MBBS3; Peter Jones, MD3; Michele Burrington, RD, RN; Chu-Huang Chen, MD, PhD3; Allyson Clark Gardner,MS, RD; Molly Gee, MEd, RD; Sharon Griggs; Michelle Hamilton; Veronica Holley; Jayne Joseph, RD; Julieta Palencia, RN; Jennifer Schmidt; Carolyn White

The University of Tennessee Health Science Center

University of Tennessee East. Karen C. Johnson, MD, MPH1; Carolyn Gresham, RN2; Stephanie Connelly, MD, MPH3; Amy Brewer, RD, MS; Mace Coday, PhD; Lisa Jones, RN; Lynne Lichtermann, RN, BSN; Shirley Vosburg, RD, MPH; and J. Lee Taylor, MEd, MBA

University of Tennessee Downtown. Abbas E. Kitabchi, PhD, MD1; Ebenezer Nyenwe, MD3; Helen Lambeth, RN, BSN2; Amy Brewer, MS, RD,LDN; Debra Clark, LPN; Andrea Crisler, MT; Debra Force, MS, RD, LDN; Donna Green, RN; Robert Kores, PhD

University of Minnesota Robert W. Jeffery, PhD1; Carolyn Thorson, CCRP2; John P. Bantle, MD3; J. Bruce Redmon, MD3; Richard S. Crow, MD3; Scott Crow, MD3; Susan K Raatz, PhD, RD3; Kerrin Brelje, MPH, RD; Carolyne Campbell; Jeanne Carls, MEd; Tara Carmean-Mihm, BA; Julia Devonish, MS; Emily Finch, MA; Anna Fox, MA; Elizabeth Hoelscher, MPH, RD, CHES; La Donna James; Vicki A. Maddy, BS, RD; Therese Ockenden, RN; Birgitta I. Rice, MS, RPh, CHES; Tricia Skarphol, BS; Ann D. Tucker, BA; Mary Susan Voeller, BA; Cara Walcheck, BS, RD

St. Luke's Roosevelt Hospital Center Xavier Pi-Sunyer, MD1; Jennifer Patricio, MS2; Stanley Heshka, PhD3; Carmen Pal, MD3; Lynn Allen, MD; Lolline Chong, BS, RD; Marci Gluck, PhD; Diane Hirsch, RNC, MS, CDE; Mary Anne Holowaty, MS, CN; Michelle Horowitz, MS, RD; Nancy Rau, MS, RD, CDE; Dori Brill Steinberg, BS

University of Pennsylvania Thomas A. Wadden, PhD 1; Barbara J Maschak-Carey, MSN,CDE 2; Robert I. Berkowitz, MD 3; Seth Braunstein, MD, PhD 3 ; Gary Foster, PhD 3; Henry Glick, PhD 3; Shiriki Kumanyika, PhD, RD, MPH 3; Stanley S. Schwartz, MD 3 ; Michael Allen, RN; Yuliis Bell; Johanna Brock; Susan Brozena, MD; Ray Carvajal, MA; Helen Chomentowski; Canice Crerand, PhD; Renee Davenport; Andrea Diamond, MS, RD; Anthony Fabricatore, PhD; Lee Goldberg, MD; Louise Hesson, MSN, CRNP; Thomas Hudak, MS; Nayyar Iqbal, MD; LaShanda Jones-Corneille, PhD; Andrew Kao, MD; Robert Kuehnel, PhD; Patricia Lipschutz, MSN; Monica Mullen, RD, MPH

University of Pittsburgh John M. Jakicic, PhD1, David E. Kelley, MD1; Jacqueline Wesche-Thobaben, RN, BSN, CDE2; Lewis H. Kuller, MD, DrPH3; Andrea Kriska, PhD3; Amy D. Otto, PhD, RD, LDN3, Lin Ewing, PhD, RN3, Mary Korytkowski, MD3, Daniel Edmundowicz, MD3; Monica E. Yamamoto, DrPH, RD, FADA 3; Rebecca Danchenko, BS; Barbara Elnyczky; David O. Garcia, MS; George A. Grove, MS; Patricia H. Harper, MS, RD, LDN; Susan Harrier, BS; Nicole L. Helbling, MS, RN; Diane Ives, MPH; Juliet Mancino, MS, RD, CDE, LDN; Anne Mathews, PhD, RD, LDN; Tracey Y. Murray, BS; Joan R. Ritchea; Susan Urda, BS, CTR; Donna L. Wolf, PhD

The Miriam Hospital/Brown Medical School Rena R. Wing, PhD1; Renee Bright, MS2; Vincent Pera, MD3; John Jakicic, PhD3; Deborah Tate, PhD3; Amy Gorin, PhD3; Kara Gallagher, PhD3; Amy Bach, PhD; Barbara Bancroft, RN, MS; Anna Bertorelli, MBA, RD; Richard Carey, BS; Tatum Charron, BS; Heather Chenot, MS; Kimberley Chula-Maguire, MS; Pamela Coward, MS, RD; Lisa Cronkite, BS; Julie Currin, MD; Maureen Daly, RN; Caitlin Egan, MS; Erica Ferguson, BS, RD; Linda Foss, MPH; Jennifer Gauvin, BS; Don Kieffer, PhD; Lauren Lessard, BS; Deborah Maier, MS; JP Massaro, BS; Tammy Monk, MS; Rob Nicholson, PhD; Erin Patterson, BS; Suzanne Phelan, PhD; Hollie Raynor, PhD, RD; Douglas Raynor, PhD; Natalie Robinson, MS, RD; Deborah Robles; Jane Tavares, BS

The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio Steven M. Haffner, MD1; Helen P. Hazuda, Ph.D.1; Maria G. Montez, RN, MSHP, CDE2; Carlos Lorenzo, MD3; Charles F. Coleman, MS, RD; Domingo Granado, RN; Kathy Hathaway, MS, RD; Juan Carlos Isaac, RC, BSN; Nora Ramirez, RN, BSN; Ronda Saenz, MS, RD

VA Puget Sound Health Care System / University of Washington Steven E. Kahn, MB, ChB1; Brenda Montgomery, RN, MS, CDE2; Robert Knopp, MD3; Edward Lipkin, MD3; Dace Trence, MD3; Terry Barrett, BS; Joli Bartell, BA; Diane Greenberg, PhD; Anne Murillo, BS; Betty Ann Richmond, MEd; Jolanta Socha, BS; April Thomas, MPH, RD; Alan Wesley, BA

Southwestern American Indian Center, Phoenix, Arizona and Shiprock, New Mexico William C. Knowler, MD, DrPH1; Paula Bolin, RN, MC2; Tina Killean, BS2; Cathy Manus, LPN3; Jonathan Krakoff, MD3; Jeffrey M. Curtis, MD, MPH3; Justin Glass, MD3; Sara Michaels, MD3; Peter H. Bennett, MB, FRCP3; Tina Morgan3; Shandiin Begay, MPH; Paul Bloomquist, MD; Teddy Costa, BS; Bernadita Fallis RN, RHIT, CCS; Jeanette Hermes, MS,RD; Diane F. Hollowbreast; Ruby Johnson; Maria Meacham, BSN, RN, CDE; Julie Nelson, RD; Carol Percy, RN; Patricia Poorthunder; Sandra Sangster; Nancy Scurlock, MSN, ANP-C, CDE; Leigh A. Shovestull, RD, CDE; Janelia Smiley; Katie Toledo, MS, LPC; Christina Tomchee, BA; Darryl Tonemah, PhD

University of Southern California Anne Peters, MD1; Valerie Ruelas, MSW, LCSW2; Siran Ghazarian, MD2; Kathryn (Mandy) Graves Hillstrom, EdD,RD,CDE; Kati Konersman, MA, RD, CDE; Sara Serafin-Dokhan

Coordinating Center

Wake Forest University Mark A. Espeland, PhD1; Judy L. Bahnson, BA, CCRP3; Lynne E. Wagenknecht, DrPH3; David Reboussin, PhD3; W. Jack Rejeski, PhD3; Alain G. Bertoni, MD, MPH3; Wei Lang, PhD3; Michael S. Lawlor, PhD3; David Lefkowitz, MD3; Gary D. Miller, PhD3; Patrick S. Reynolds, MD3; Paul M. Ribisl, PhD3; Mara Vitolins, DrPH3; Haiying Chen, PhD3; Delia S. West, PhD3; Lawrence M. Friedman, MD3; Brenda L. Craven, MS, CCRP2; Kathy M. Dotson, BA2; Amelia Hodges, BS, CCRP2; Carrie C. Williams, MA, CCRP2; Andrea Anderson, MS; Jerry M. Barnes, MA; Mary Barr; Daniel P. Beavers, PhD; Tara Beckner; Cralen Davis, MS; Thania Del Valle-Fagan, MD; Patricia A. Feeney, MS; Candace Goode; Jason Griffin, BS; Lea Harvin, BS; Patricia Hogan, MS; Sarah A. Gaussoin, MS; Mark King, BS; Kathy Lane, BS; Rebecca H. Neiberg, MS; Michael P. Walkup, MS; Karen Wall, AAS; Terri Windham

Central Resources Centers

DXA Reading Center, University of California at San Francisco Michael Nevitt, PhD1; Ann Schwartz, PhD2; John Shepherd, PhD3; Michaela Rahorst; Lisa Palermo, MS, MA; Susan Ewing, MS; Cynthia Hayashi; Jason Maeda, MPH

Central Laboratory, Northwest Lipid Metabolism and Diabetes Research Laboratories Santica M. Marcovina, PhD, ScD1; Jessica Chmielewski2; Vinod Gaur, PhD4

ECG Reading Center, EPICARE, Wake Forest University School of Medicine Elsayed Z. Soliman MD, MSc, MS1; Ronald J. Prineas, MD, PhD1; Charles Campbell2; Zhu-Ming Zhang, MD3; Teresa Alexander; Lisa Keasler; Susan Hensley; Yabing Li, MD

Diet Assessment Center, University of South Carolina, Arnold School of Public Health, Center for Research in Nutrition and Health Disparities Robert Moran, PhD1

Hall-Foushee Communications, Inc. Richard Foushee, PhD; Nancy J. Hall, MA

Federal Sponsors

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Mary Evans, PhD; Barbara Harrison, MS; Van S. Hubbard, MD, PhD; Susan Z.Yanovski, MD; Robert Kuczmarski, PhD

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Lawton S. Cooper, MD, MPH; Peter Kaufman, PhD, FABMR

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Edward W. Gregg, PhD; David F. Williamson, PhD; Ping Zhang, PhD

Funding and Support

This study is supported by the Department of Health and Human Services through the following cooperative agreements from the National Institutes of Health: DK57136, DK57149, DK56990, DK57177, DK57171, DK57151, DK57182, DK57131, DK57002, DK57078, DK57154, DK57178, DK57219, DK57008, DK57135, and DK56992. The following federal agencies have contributed support: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute of Nursing Research; National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities; NIH Office of Research on Women's Health; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The Indian Health Service (I.H.S.) provided personnel, medical oversight, and use of facilities. The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the I.H.S. or other funding sources.

Additional support was received from The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions Bayview General Clinical Research Center (M01RR02719); the Massachusetts General Hospital Mallinckrodt General Clinical Research Center and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology General Clinical Research Center (M01RR01066); the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center General Clinical Research Center (M01RR00051) and Clinical Nutrition Research Unit (P30 DK48520); the University of Tennessee at Memphis General Clinical Research Center (M01RR0021140); the University of Pittsburgh General Clinical Research Center (GCRC) (M01RR000056), the Clinical Translational Research Center (CTRC) funded by the Clinical & Translational Science Award (UL1 RR 024153) and NIH grant (DK 046204); the VA Puget Sound Health Care System Medical Research Service, Department of Veterans Affairs; and the Frederic C. Bartter General Clinical Research Center (M01RR01346).

The following organizations have committed to make major contributions to Look AHEAD: FedEx Corporation; Health Management Resources; LifeScan, Inc., a Johnson & Johnson Company; OPTIFAST® of Nestle HealthCare Nutrition, Inc.; Hoffmann-La Roche Inc.; Abbott Nutrition; and Slim-Fast Brand of Unilever North America.

Some of the information contained herein was derived from data provided by the Bureau of Vital Statistics, New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene for providing vital statistics data.

Footnotes

Principal Investigator

Program Coordinator

Co-Investigator

All other Look AHEAD staffs are listed alphabetically by site.

References

- 1.Brownell KD, Wadden TA. Etiology and treatment of obesity: Understanding a serious, prevalent, and refractory disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992;60(4):505–517. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.4.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldberg JH, Kiernan M. Innovative techniques to address retention in a behavioral weight-loss trial. Health Educ Res. 2005;20(4):439–447. doi: 10.1093/her/cyg139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wadden TA, Womble LG, Sarwer DB, Berkowitz RI, Clark VL, Foster GD. Great expectations: “I'm losing 25% of my weight no matter what you say”. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71(6):1084–1089. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.6.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kong W, Langlois MF, Kamga-Ngande C, Gagnon C, Brown C, Baillargeon JP. Predictors of success to weight-loss intervention program in individuals at high risk for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;90(2):147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teixeira PJ, Going SB, Houtkooper LB, et al. Pretreatment predictors of attrition and successful weight management in women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28(9):1124–1133. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ryan DH, Espeland MA, Foster GD, et al. Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes): Design and methods for a clinical trial of weight loss for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes. Control Clin Trials. 2003;24(5):610–628. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(03)00064-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Look AHEAD Research Group. Pi-Sunyer X, Blackburn G, et al. Reduction in weight and cardiovascular disease risk factors in individuals with type 2 diabetes: One-year results of the Look AHEAD trial. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(6):1374–1383. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Look AHEAD Research Group. Wing RR. Long-term effects of a lifestyle intervention on weight and cardiovascular risk factors in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus: Four0year results of the Look AHEAD trial. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(17):1566–1575. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Look Ahead Research Group. Bray G, Gregg E, et al. Baseline characteristics of the randomised cohort from the Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) study. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2006;3(3):202–215. doi: 10.3132/dvdr.2006.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. SF-36 physical and mental health summary scales: A user's manual. New England Medical Center; Boston, MA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beck AT, Brown GK, Steer RA. Beck depression inventory-II. Psychological Corp; San Antonio, TX: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paffenbarger RS, Jr, Hyde RT, Wing AL, Hsieh CC. Physical activity, all-cause mortality, and longevity of college alumni. N Engl J Med. 1986;314(10):605–613. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198603063141003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Look AHEAD Research Group. Wadden TA, West DS, et al. The Look AHEAD study: A description of the lifestyle intervention and the evidence supporting it. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14(5):737–752. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raynor HA, Jeffery RW, Ruggiero AM, Clark JM, Delahanty LM. Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) Research Group. Weight loss strategies associated with BMI in overweight adults with type 2 diabetes at entry into the Look AHEAD (action for health in diabetes) trial. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(7):1299–1304. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jakicic JM, Jaramillo SA, Balasubramanyam A, et al. Effect of a lifestyle intervention on change in cardiorespiratory fitness in adults with type 2 diabetes: Results from the Look AHEAD study. Int J Obes (Lond) 2009;33(3):305–316. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spitzer RL, Devlin M, Walsh BT, et al. Binge eating disorder: A multi-site field trial of the diagnostic criteria. Int J Eat Disord. 1992;11:191–203. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fabricatore AN, Wadden TA, Moore RH, Butryn ML, Heymsfield SB, Nguyen AM. Predictors of attrition and weight loss success: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther. 2009;47(8):685–691. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang MW, Brown R, Nitzke S. Participant recruitment and retention in a pilot program to prevent weight gain in low-income overweight and obese mothers. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:424. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clark MM, Niaura R, King TK, Pera V. Depression, smoking, activity level, and health status: Pretreatment predictors of attrition in obesity treatment. Addict Behav. 1996;21(4):509–513. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(95)00081-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.SAS Institute I Help and documentation. 2000 - 2004;SAS 9.2.

- 21.Dalle Grave R, Calugi S, Molinari E, et al. Weight loss expectations in obese patients and treatment attrition: An observational multicenter study. Obes Res. 2005;13(11):1961–1969. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Honas JJ, Early JL, Frederickson DD, O'Brien MS. Predictors of attrition in a large clinic-based weight-loss program. Obes Res. 2003;11(7):888–894. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]