Awareness and activities

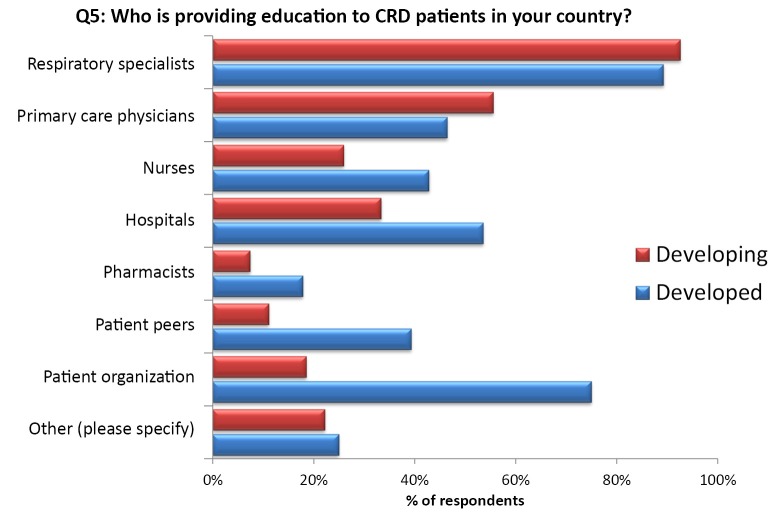

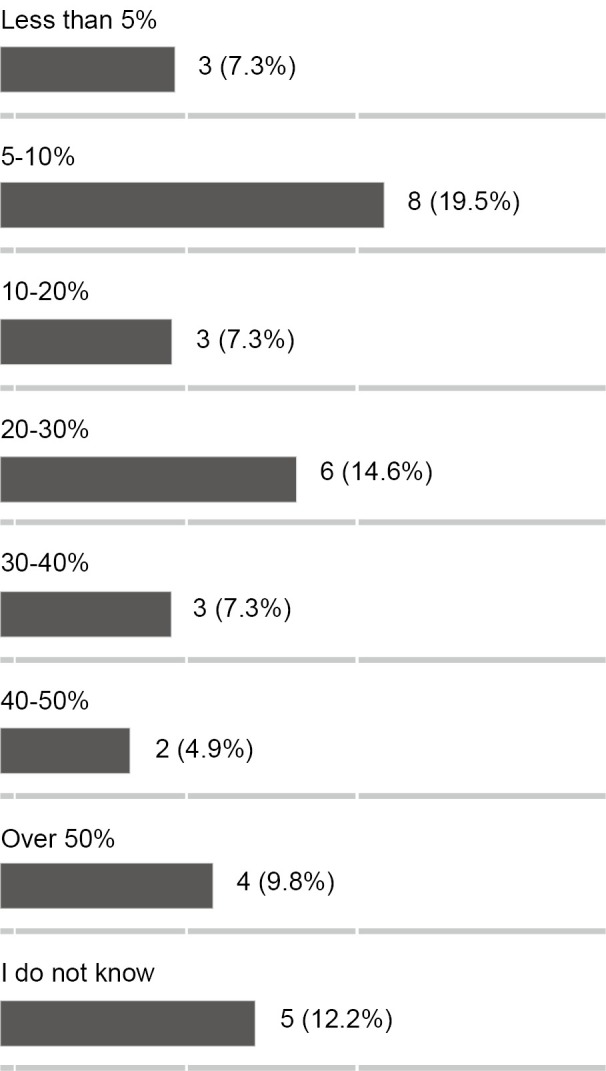

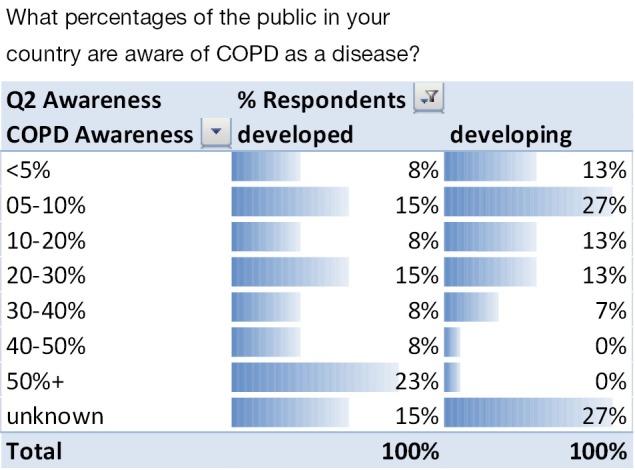

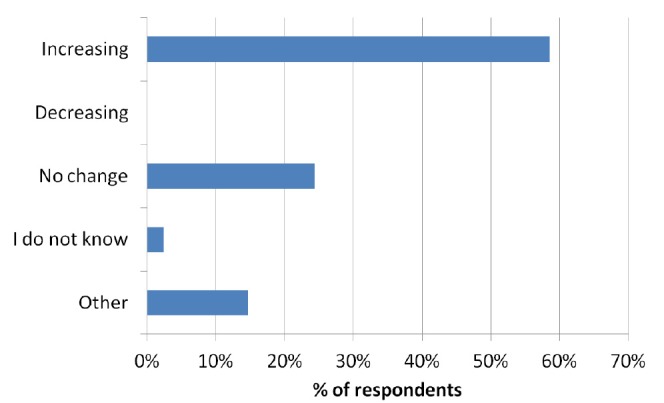

The International COPD Coalition (ICC) has been working to improve COPD awareness and action since it was organized in 2001. Shortly after the launch of ICC in 2001 we did an omnibus phone and in-person interview study of COPD awareness in Canada, Brazil, China, and Germany and found that global public awareness of COPD was very limited. It ranged from 4% of the public in Brazil to about 10% in Germany. Increasing public awareness was a high priority to help COPD patients. This was important because these data showed us early on how few people knew about the disease and how important it was to increase awareness globally. By now—in 2014—many countries’ COPD leaders are tracking public awareness of COPD every year. The data from a survey (Figure 1) that ICC has just completed of estimated COPD awareness in 41 different countries (26 developed and 15 developing countries) as provided by the ICC COPD patient organization leaders from each of the countries shows clearly that there has been an overall global increase in awareness since 2001, with almost 37% of the countries reporting public awareness figures of 20% or greater. Figure 2 shows the differences in the estimates of awareness from developed and developing countries. 31% of developed countries have public awareness greater than 40%, while 0% of developing countries have such high awareness. However, even though developing countries have lower awareness of COPD, Figure 3 indicates that awareness has been increasing in almost 60% of all countries, while no countries report decreasing awareness.

Figure 1.

COPD awareness. What percentages of the public in your country are aware of COPD as a disease?

Figure 2.

ICC survey 3-COPD awareness.

Figure 3.

Have there been any changes in the past several years in COPD awareness among the public in your country?

Mass communication by television and the internet have made a big difference in expanding COPD awareness. In the US, direct-to-consumer advertising of COPD products has played a key role, with its broad reach and frequent reminders. It is important to realize that overall COPD awareness in a country can be rapidly increased by well-planned communications, especially if the government, the medical and commercial leaders, and the patient organizations play active roles with the mass media.

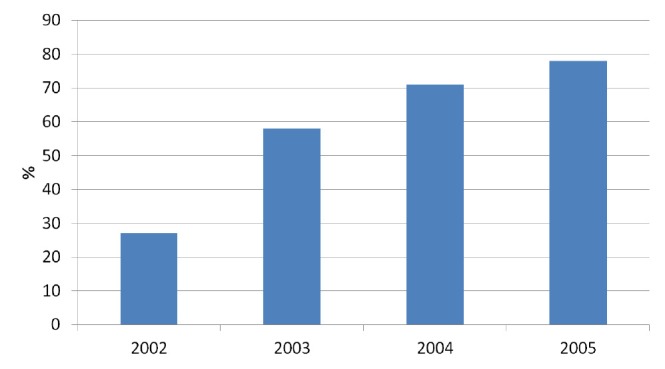

Respiratory medical professional groups in Norway performed phone surveys from 2002 to 2005 in conjunction with a national COPD awareness initiative and asked a random sample of adults in Norway “Have you ever heard about COPD?” During the four years of this campaign the positive responses to this question went from 27% to 78% (Figure 4) (1). The success of the Norwegian awareness campaign has greatly improved our understanding of how to increase COPD awareness. The yearly World COPD Day campaigns, which ICC initiated in 2002 in collaboration with the GOLD initiative, have helped many countries build COPD awareness and action.

Figure 4.

Have you ever heard about COPD? (Adapted from the Clinical Respiratory Journal).

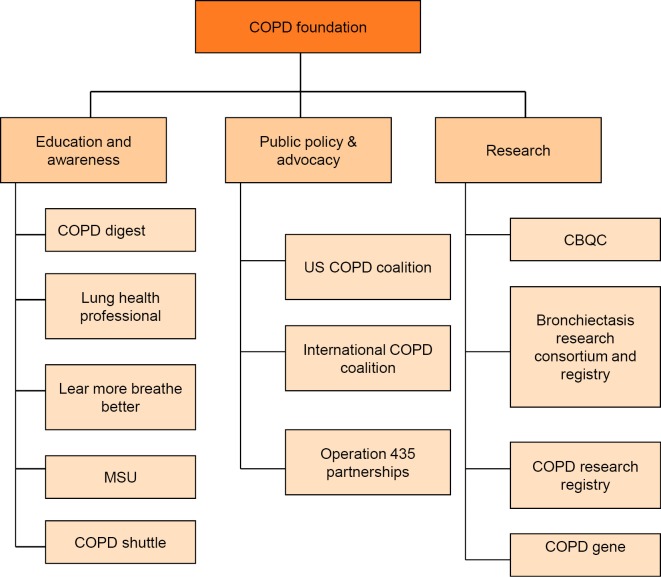

The activities of national respiratory patient organizations are crucial in proposing and implementing improvements in respiratory disease prevention and treatment. ICC has surveyed these activities globally as well. In wealthy countries, like the US, a great deal of COPD education and promotion is being done. Particularly successful have been the activities organized by the US COPD Foundation. Figure 5 shows the algorithm that summarizes the comprehensive programs that the US COPD Foundation conducts for COPD education and awareness promotion in the US. Their work includes public policy liaison, COPD advocacy, and COPD research!

Figure 5.

US COPD Foundation algorithm of services (2).

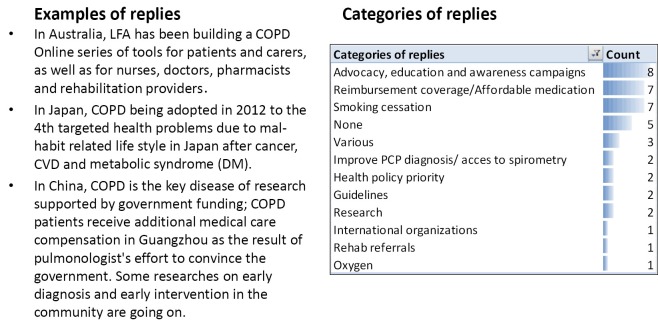

Figure 6 presents top line information from an ICC survey of the major activities globally of COPD organizations in their countries. There are many creative and effective educational programs of different types that have been carried out globally to serve the many different countries throughout the world. Some resemble those in the US, but most countries have their own COPD priorities and their own means of communication. In the developing world there are limited budgets and fewer COPD activities are possible. Appendix 1 contains verbatim remarks from national ICC leaders concerning country-specific COPD patient organization activities. They include different approaches to COPD education, prevention, and management.

Figure 6.

What is the most important action to benefit COPD patients that is going on in your country?

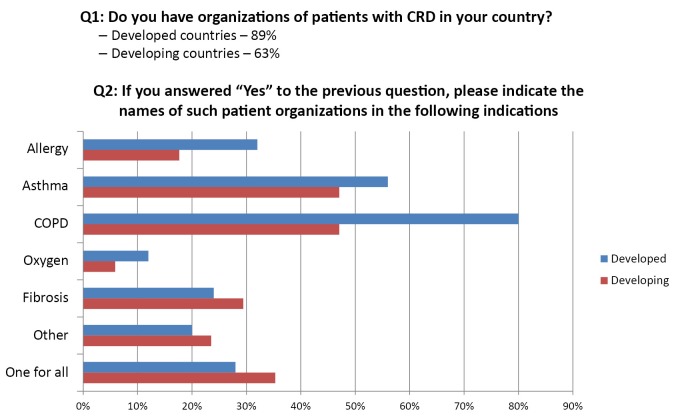

Budgetary limitations on respiratory patient organizations, particularly in the developing world, limit their ability to carry out educational programs. Figure 7 presents data from an ICC survey in press in the Journal of Thoracic Disease. It tabulates the presence of various respiratory patient organizations globally. These organizations focus their education and advocacy on different respiratory diseases (asthma, COPD, pulmonary fibrosis, airway allergy) and treatments (oxygen). Only about one third of the countries have patient advocacy organizations for most chronic respiratory diseases. However, 80% of the developed countries have COPD patient organizations. Only about 45% of developing countries have them.

Figure 7.

Availability of patient organizations.

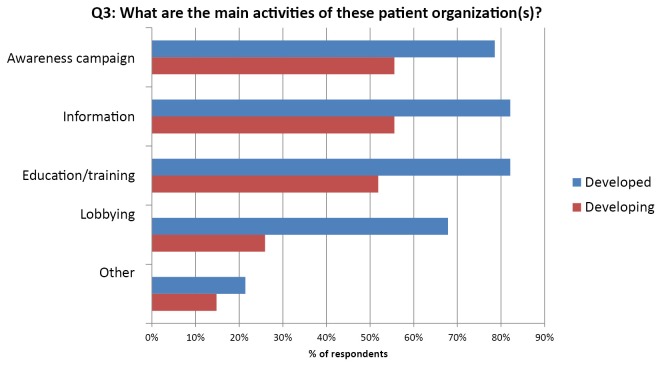

Figure 8 shows a global picture of the major categories of activities of respiratory patient organizations. The kinds of activities are the same in both developed and developing countries; however, because of financial limitations in developing countries, their activities are only about half of those in developed countries.

Figure 8.

Activities of patient organizations.

Finally, we see which groups of educators provide respiratory patient education in developed and developing countries (Figure 9). Clearly, respiratory specialists are the major providers of education for respiratory patients worldwide. However, the ICC survey shows some deficiencies in education. First, little education is provided by COPD patient groups in developing countries. This probably results both from the shortage of COPD patient organizations in developing countries as well as their limited resources. Another concern that is raised from these data is that primary care physicians, who do most of the care for respiratory patients, apparently do little patient education.

Figure 9.

Providers of CRD patient education.

These data suggest that developing countries need assistance to develop their COPD patient organizations. They need this support so they can provide needed education, improve care, advocate for COPD patients rights, and improve COPD prevention and awareness in their countries.

The need for more efforts and resources in developing countries is highlighted by Prof. Yousser Mohammad, ICC Co-Chair, and her colleagues in their article (in press) in the Journal of Thoracic Disease. They observe that 63% of global deaths result from non-communicable diseases. A percentage of 80 of global deaths occur in low and middle income countries and 90% of global deaths from COPD occur in developing countries (3). To deal with respiratory diseases globally, the efforts must increase in developing countries.

Patient Micro-Organizations

Prof. Muhammad and her colleagues in the WHO Global Alliance against Chronic Respiratory Disease have a concept to improve respiratory patient education in developing countries through what they call Patient Micro-Organizations (4). These COPD patient groups are built locally and from the ground up rather than being mandated from top down by health ministries. They are organized around local institutions like hospitals and schools and they develop and provide educational materials about COPD for health care professionals and patients that are appropriate for their country and region. A number of these patient micro-organizations have been successfully established in developing countries. ICC believes that such local COPD organizations can make a big difference in COPD awareness and action. Patient Micro-Organizations follow the ICC philosophy, which is to think globally, but act locally.

Lack of progress

The final question is whether or not the global medical community is making progress in preventing and managing COPD. Data from the World Health Organization suggests that the progress is very limited. COPD continues to increase as a global non-communicable disease epidemic. Stroke and coronary heart disease, the other leading non-communicable diseases, have had their mortality rates decrease. COPD has increased in its effects on years lived with disability (referred to as YLDs) (5). The World Health Organization Burden of Disease report recently compared data from 1990 and 2010 and showed a 46% rise in YLDs globally. The global deaths caused by COPD have made it the 3rd major cause of death in 2010, up from 4th in 1990 (6).

In many countries, such as the US, life expectancy has shown a small increase from 1990 to 2010; however healthy life expectancy, which is years lived without disability has actually decreased. That is, people are living longer but with more disability and less good health. This is especially true of COPD patients. Years lived with disability from COPD in the US increased from 1.3 million in 1990 to 1.8 million in 2010 (5). As respiratory health care providers, we want to improve life expectancy with COPD, but we want it to be healthy life expectancy.

In years lost prematurely (YLLs) from COPD, the global regions most severely affected are the Caribbean, Oceania, north and sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America (5).

Although COPD awareness and activities have increased globally, COPD continues to increase as a deadly and costly health menace. In the second part of this report we will examine the efforts of the four key global medical partners in combating COPD and other respiratory diseases to try to understand why the progress has been so limited.

Acknowledgements

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix 1. This appendix provides the verbatim responses from all the ICC leaders who replied to the full questionnaire. It includes the detailed descriptions of the COPD patient activities in each of the countries represented.

| Q4 | Q5 | Q6 |

|---|---|---|

| What percetage (%) of COPD patients cannot afford state-of-the-art medications in your country? | How do the patients deal in your country with the expense of COPD care if they do not have adequate financial resources? | What is your country? |

| 30-40 | It varies: some go without, some find help for paying for meds, some of the pharma companies have programs for low income folks | USA |

| 10-20 | Limited resourses at Govt Hospitals and voluntary agencies. I have established COPD Club for patients organising meetings and issue of medicines to the poor | India |

| Less than 5 | Consult social workers’ office | South Korea |

| Over 50 | Public nor we gain health insurance | Norway |

| 30-40 | Liquid oxygen cost 4,300 per month In my case half of this cost comes out of my pocket, as in my case as with my case as with others, it may require substantial loans and re-mortgage of my home and others, there are grey areas in provincial coverage | Canada |

| Over 50 | Patients only seek medical care when they are in acute exacerbation stage. Patients use only the cheap, affordable medications that are less effective | China |

| Less than 5 | The need is sometimes for caregiver support, for respite and for home services | Canada |

| 20-30 | Deprived of care | USA |

| I do not know | Most of the ones I deal with here simply do not use their meds the way they are ordered if they can’t afford them. They will either not get the scripts filled or they will only use the expensive meds when they are having a hard time | USA |

| 30-40 | They are covered “in this moment” put its too expensive | Castellon-Valencian comunity-Spain |

| 20-30 | Some access government funded or charity care, some do without | US |

| Less than 5 | They just suffer and eventually die if they have no access to even oxygen | Philippines |

| I do not know | They do not they go without a lot of the time | Bermuda |

| 30-40 | They look for the lowest priced products, get family help or Civil society help. They quit smoking | Syrian Arab Republic |

| 5-10 | Medicare in the U.S. | United States of America |

| 20-30 | Rx assistance programs | USA |

| Over 50 | They can get some of the medication for free | Brazil |

| I do not know | Many qualify for subsidy schemes. Our patient groups have not indicated concerns in this area with the exception of oxygen access | Australia |

| Over 50 | They use aminophylline tbl. It is the cheapest drug. Most COPD patients believe they have asthma. COPD is not recognized as a distinct chronic disease. More than 50% of population smoke | Serbia |

| 5-10 | The patients either do not see the doctor or they do not pick up the prescribed medication | Czech Republic |

| Over 50 | They remain under-treated. Sometimes get financial supports from NGOs | Bangladesh |

| 5-10 | There is “universal health insurance” (medicare) for everyone for medical and allied health care plus medications, PLUS those who can afford it buy extra private insurance | Australia |

| Guessed estimate, it’s also about access | COPD care is generally well state funded access and personal prioritising can be financial strain | New Zealand |

| I do not know | If the compensation of the Social Insurance Service do not cover expences of the medicine, patients are useing only low cost medicine such as the inhaled opening medice instead of corticosteroid or others | Finland |

| 0 | Care is paid by national health insurance | Austria |

| Over 50 | We are using Theophyllin and Triotopium as these two drugs are less costly than others | Bangladesh |

| Less than 5 | They have free care | Italy |

| Less than 5 | All COPD patients get their medicines on blue prescription, which in reality means free after a low amount early in the year | Norway |

| I do not know | They do not comply with treatment | Pakistan |

| 30-40 | They ask help from social workers and at the hospital | Portugal |

| I do not know | Buy meds from India I do not believe anyone in this country is denied health care | America |

| Are payed from the state we have only a little ticket | The poor people do not pay the ticket | Italy |

| I do not know | They were not treated or discontinued therapy | BULGARIA, Association of Bulgarian with Bronchial Asthma, Alergi and COPD/ABBA/Diana Hadzhiangelova, Chairman of ABBA www.asthma-bg.com asthma@mail.bg |

| Drug treatment is cheapest in the world. But poverty is also amongst biggest in the world despite economic growth which has not been entirely non-inclusive | Under diagnosis under monitoring and under-treatment is rampant. Non drug components such as smoking cessation, doctor patient motivational sessions, action plans, rehabilitation services, care giver training, home hospital care, end of life issues-all these are practically unheard of in India | Incredible India |

| Because they do not visit their primary care doctor | Government provide free medications for all registered in primary care COPD patients | Kazakhstan |

| Less than 5 | In my country there is a public health service for everybody | Italy |

| Less than 5 | 90-70% of all medical cost are covered by public insurance system in Japan. The coverage extends to virtually all people | Japan |

| Over 50 | If patients can not cover the expenses they use aminophylline tablets | Serbia |

| 5-10 | If elderly they are OK. If not they are on their own | USA |

| Over 50 | They do not unfortunately | Philippines |

| Less than 5 | Not applicable | UK |

References

- 1.Gulsvik A, Myrseth SE, Henrichsen SH, et al. Increased awareness of COPD in the Norwegian population. Clin Respir J 2007;1:118-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walsh JW. The evolving role of COPD patient advocacy organizations for COPD. J Thorac Dis 2012;4:676-80 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Measuring the global burden of disease. N Engl J Med 2013;369:448-57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Global alliance against chronic respiratory diseases (GARD). (2013). Available online: http://www.who.int/gard/en/

- 5.Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2163-96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2197-223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]