Abstract

Objective

To address a gap in understanding of verbal exchange (oral and aural) health literacy by describing the systematic development of a verbal exchange health literacy (VEHL) definition and model which hypothesizes the role of VEHL in health outcomes.

Methods

Current health literacy and communication literature was systematically reviewed and combined with qualitative patient and provider data that were analyzed using a grounded theory approach.

Results

Analyses of current literature and formative data indicated the importance of verbal exchange in the clinical setting and revealed various factors associated with the patient-provider relationship and their characteristics that influence decision making and health behaviors. VEHL is defined as the ability to speak and listen that facilitates exchanging, understanding, and interpreting of health information for health-decision making, disease management and navigation of the healthcare system. A model depiction of mediating and influenced factors is presented.

Conclusion

A definition and model of VEHL is a step towards addressing a gap in health literacy knowledge and provides a foundation for examining the influence of VEHL on health outcomes.

Practice Implications

VEHL is an extension of current descriptions of health literacy and has implications for patient-provider communication and health decision making.

Keywords: health literacy, oral exchange, oral literacy, patient-provider communication

1. Introduction

Literacy is a skill that when combined with social skills becomes “functional literacy” and enables effective participation in society [1]. Health literacy is usually discussed in terms of functional health literacy and commonly defined as: “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions”(p.32) [2, 3]. In 2004, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) described the array of skills subsumed by health literacy to include reading, writing, speaking, listening and numeracy [2]. Yet, to date, most of what we know about health literacy's role in health outcomes is based on reading and numeracy skills. There has been minimal examination of the roles of speaking or listening skills and their impact on overall functional health literacy. Speaking is often referred to as “oral” and listening as “aural” health literacy. Oral health literacy most often refers to dental health literacy in the literature; therefore, we propose “verbal exchange” to represent the speaking and listening skills required for two-way communication.

Over one-third of U.S. adults is estimated to have inadequate health literacy [4] which has been linked negatively to health issues, such as poor asthma outcomes [5], poor diabetes control [6, 7], poor medication adherence [6, 8, 9], and more hospitalizations and less preventive care [10]. Inadequate health literacy also has been found to directly contribute to known health disparities in vulnerable populations [10-21] and accounts for an estimated $106-$238 billion in costs of healthcare insufficiency [22]. Patients with limited health literacy are reported to have less interest in shared health decision-making [23-26] which has implications for treatment adherence and health outcomes [27, 28]. Complicating the patient's experience is that healthcare providers have difficulty detecting patients with limited health literacy [29, 30].

The communication of everyday information occurs on multiple levels, including interpersonal, group, organizational, mass, and technological, through two primary formats, oral and written [31]. Despite multiple communication levels and modes, patients most often prefer and exchange a large percentage of personal health information through interpersonal verbal communication with the healthcare provider [32, 33]. Unfortunately, patients report understanding and retaining only about 50% of the information their providers discuss [34, 35]. Moreover, patients with limited health literacy are less likely to ask questions [36], seek information from print resources [37], or process (i.e., remember) verbally communicated medication instructions [38], further contributing to patients' inability to use information effectively. Speaking and listening skills are considered more important than reading and numeracy in patient self-advocacy within the healthcare system [39]. Two studies that have examined these skills, using Woodcock-Johnson test components “understanding directions” to determine listening skills and “story recall” to asses speaking, found a significant association between understanding and health outcomes [40, 41].

Verbal exchange skills are key to patient understanding and use of health information that impact health outcomes [2, 42, 43]. Despite this important role, the verbal exchange aspects of health literacy have not been defined nor described to the degree that reading and numeracy constructs of health literacy have. There is a need to better understand how verbal exchange of individually relevant information during the patient–provider interaction [44] impacts health outcomes and inequalities. An operational definition of “verbal exchange health literacy” (VEHL) and theoretical model of VEHL are first steps in addressing this need and can provide the foundation to use VEHL to inform intervention design and educational approaches, and its evaluation, including in outcomes research. The focus of this paper is to describe the multi-step development of the proposed definition and model of VEHL presented herein.

2. Methods

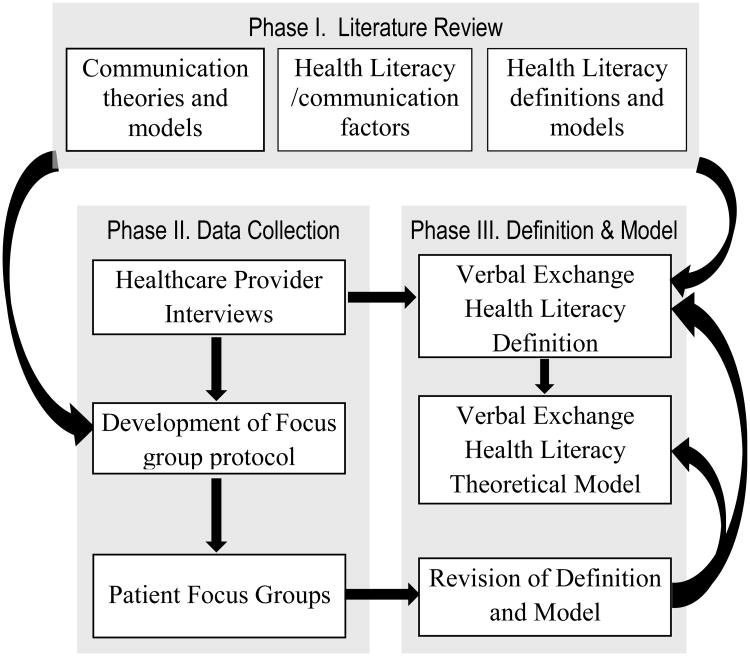

The development of a definition and model of VEHL was a multi-step process (see Figure 1) in three interconnected phases. Details of these phases are described below.

Figure 1. Systematic Protocol for Development of a Verbal Exchange Health Literacy Definition and Theoretical Model.

Phase I - Review of health literacy and communication literature

We reviewed the health literacy and communication literature to identify current health literacy definitions, models, theories and categorize contributing factors and influences on verbal exchange. PubMed and Google Scholar search engines were used; the following search terms were included: health literacy, functional health literacy, verbal exchange communication, health literacy AND decision-making, oral literacy, oral health literacy, aural literacy, aural health literacy, health literacy AND speaking, health literacy AND listening, health literacy AND health outcomes, patient-provider communication, model of health literacy, health literacy framework, theory of health literacy, and communication theory. As part of the literature review, existing conceptual models of health literacy were reviewed to identify predisposing influences (e.g., demographics, healthcare system characteristics) on health literacy and their inter-relationships. Factors identified as related to health literacy or mediating its role in health outcomes were examined for their probable relationship to VEHL. The potential influences on VEHL and mediators of its role in health outcomes were then grouped using a card sort procedure to identify like factors. Each group of factors was then reviewed and assigned a “theme” label, which serve as the bases for the VEHL factors, and the wording of a VEHL definition.

Phase II – Data Collection

a. Provider interviews

As part of an exploratory health literacy study, pediatric healthcare providers were asked to use their clinical judgment to rate the health literacy of their patients' caregivers as adequate, marginal, or inadequate, immediately following the child's clinic visit. One-on-one in-depth interviews were then completed with providers to identify the specific factors they considered in assessing a caregiver's health literacy, and how their assessment influenced what and how treatment recommendations were communicated. Themes were identified and prioritized using two stages proposed by Thomas and Harden: stage 1 involved coding interviews based on patterns of meaning within the text, and stage 2 identified descriptive themes from these patterns [45]. A constant comparative method allowed concomitant examination of data across interviews and to review interview responses after coding to ensure no themes were overlooked [46].

b. Development of qualitative questions for patient focus groups

From the first two steps, focus group questions and a moderator's guide were developed to elicit the patient perspective of factors identified in Phase I and to further elucidate relationships among the identified potential VEHL factors.

c. Patient Focus Groups

Six focus groups were conducted, two with each of three health literacy levels as determined by the Newest Vital Sign [47]: Low (high-likelihood of limited), Mid (possibility-of-limited), and High (adequate). One focus group with patients representing each level was held in Alabama and in Michigan. IRB approvals from the University of Alabama at Birmingham and the University of Michigan were received prior to recruitment and data collection. Patients were recruited from federally qualified healthcare centers and a family medicine clinic. Group discussions were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Analyses were conducted using a grounded theory approach [48], with each focus group coded separately with thematic categories developed across all transcripts. Four independent researchers coded each transcript with consensus resolution (e.g., adding or collapsing codes) to resolve coding discrepancies. Themes and sub-themes were identified by the two authors and given priority ratings by their frequency of appearance in the transcripts.

Phase III – Development of the VEHL Definition and Model

a. Draft of the VEHL definition and model

Findings from Phase I and the healthcare provider interviews provided the basis for an initial draft of a VEHL definition and the constructs of the model. Relationships among constructs also were delineated.

b. Refinement of the VEHL definition and model

Themes from the focus group guided revision and refinement of the VEHL definition and model. Factors identified by patients were added with relationships among factors further specified.

3. Results

Phase I - Review and thematic identification from the literature

Reports from the IOM and Healthy People work groups on health communication and health literacy were used to identify the primary types of health tasks experienced by patients: clinical, prevention, and navigation of the healthcare system [49-51]. Factors related to a patient's ability to complete these tasks, along with basic speaking and listening skills necessary for verbal exchange, were identified from existing health literacy frameworks, communication theories, and research on patient-provider communication.

a. Communication theories and models

Two communication theories/models were identified as particularly applicable to verbal exchanges within the healthcare setting: McGuire's Communication/Persuasion Model (McGuire) [52] and Watzlawick, Beavan and Jackson's Interactional Theory (Interactional Theory) [53].

McGuire describes input and output variables that effect communication. “Receiver” characteristics, such as demographics, ability, personality and lifestyle, impact communication and are considered the most important of the five input variables as other variables rely heavily on them. For the receiver (patient), the credibility of the source (healthcare provider), the type of information and repetitiveness of the message (health condition and acute vs. chronic messages), the modality and context of the channel (in person – verbal vs. written) and the destination or specificity of the message (specific behavior vs. general admonition) all impact their ability to understand and use health information. Communication, as an exchange, is bi-directional with the provider also in the role of the listener (receiver) of the verbal (channel) description of symptoms/history (message) from the patient (source). This exchange may be positive or negative and in some cases may not be effective if the patient or provider do not fully participate.

Interactional Theory proposes that communication has both content and relationship components, and that it is either symmetrical (same power balance) or complementary (differing power balance). Communication in the medical setting has disease or health specific content while the relationship reflects the context of the communication (number and type of previous interactions). As healthcare providers are usually in a more powerful position as the “expert,” communication is most often complementary.

These theories support inclusion of both patient and provider characteristics, with their relationship mediating the clinical exchange. Particularly, we adopted patient characteristics, health issue context, and history and type of previous exchanges as factors influencing VEHL.

b. Health literacy and communication factors

We found two primary sources of factors to consider: those identified by patients and those identified empirically. We drew upon both to specify factors and relationships for the VEHL model.

Jordan et al. report seven patient-identified capacities as important in seeking, understanding and utilizing health information within the healthcare setting [54]. In addition to knowing when and where to seek health information, the patient needs to possess verbal communication skills, assertiveness, literacy skills, the capacity to process and retain information, and application skills. We incorporated these capacities into the model under three factors in Patient Characteristics: health system experience, attributes and skills. Further, patients' identified socioeconomic (SES) circumstances, social support, provider approach to information delivery, the nature of the healthcare setting (e.g., emergency room) and emotional distress as influencing their ability to understand health information. Patients also have reported the importance of their relationship with the provider and his/her communication skills in their active involvement in their own healthcare [55]. These factors are represented in the VEHL model external to the patient characteristics. They are related to decision making (social support, SES), provider/system characteristics (provider approach, context), or relationship characteristics.

Demographic variables included in the model have been found to be associated with health literacy and patient abilities. Specifically, health literacy skills have been found to decline with age [56]. Education, which impacts health through economic and therefore lifestyle advantages, affects thinking and decision-making patterns [57].

Edwards, Davies and Edwards' meta-study report of influences on information exchange in the healthcare setting supports health literacy as critical to the information exchange that precedes decision-making (p.49) [58]. This suggested that health literacy mediates the roles of patient and provider characteristics and relationship in health decision making.

c. Health Literacy Definitions and Models

A number of health literacy frameworks focus on individual level capacity and traits while others describe health literacy in global contexts. For example, Zarcadoolas and colleagues propose an expanded model of health literacy to include domains of fundamental, science, civic and cultural literacy [59] while Nutbeam proposes health literacy in terms of the public health and societal realms [60]. These models extend into socio-ecological realms, highlighting external influences on the patient and the provider. In the VEHL model, external influences are found within both patient and provider/system level as factors that mediate the patient-provider relationship and exchange. These influencing factors include family/friends and others as well as technology (e.g., resources) and the health system (e.g., complexity and health issue).

Parker's and Nutbeam's views of health literacy focus on the intersection of the patient's skills and abilities and the healthcare system's demands and complexity [61, 62] emphasizing the role of the provider/system and the patient encounter. Roter and colleagues further develop the healthcare demand side in a framework for “oral literacy demand” [63, 64], having four separate language elements: 1) medical jargon; 2) general language complexity; 3) contextualized language; and 4) structural characteristics of dialogue [65]. Their descriptions focus on the communication demands of the interaction and are represented in the provider/system characteristics (language/communication skills; health issue context, interpersonal skills and patient-centered care).

Baker posits that beyond the individual's capacities, health literacy is influenced by the characteristics of the healthcare system [66], including the complexity of health messages. He posits that patients' use of acquired knowledge will lead to improved health outcomes over time. Similarly, in the arena of health psychology, vonWagner and colleagues propose a framework of health literacy and health related actions that includes the concept of experiential learning [67]. These frameworks suggest a reciprocal relationship between the patients' knowledge and understanding and their health literacy, as one improves so does the other, both of which influences health via decisions and behaviors.

The model developed by Paasche-Orlow and Wolf [14] focuses on the influence of health literacy on healthcare access and utilization, the patient-provider relationship, and self-care and takes into account multiple layers of influence – specifically, the structural to individual levels, as well as external factors. From this model, we adopted external influences on health outcomes.

Phase II – Qualitative data

a. The provider perspective

Themes (see Table 1) from the healthcare provider interviews (n=6) focused on the verbal exchange between the parent and providers based on the provider's experience with the parent. All six providers reported using the parent's ability to articulate the child's health history and /or prescribed treatment plan in assessing health literacy. Themes that emerged from these data represent the influence of parent attributes and skills, role expectations, history of interactions within the healthcare system, satisfaction with the relationship, knowledge and understanding, parent motivation, and the impact of parent resources on health decisions, adherence and outcomes.

Table 1. Provider Interview results and integration into the Verbal Exchange Health Literacy Model constructs.

| Construct in Model | Theme | Supporting Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics (attributes, skills)* | Patient ability |

|

| Relationship Characteristics (history and type of interactions, satisfaction with relationship, role expectations) | Expectations |

|

| Patient Psychosocial (knowledge/understanding, motivation) | Patient understanding |

|

| Patient Resources (transportation, insurance status) | Patient Resources |

|

Quotes supporting the patient characteristics represent the assessment of parent/caregiver characteristics by pediatric providers interviewed in Phase I.

b. Focus group questions/protocol

The focus group protocol arose from the first two steps which identified areas for exploration: the patient's perceived communication with their healthcare provider (types of information, understanding and ability to articulate), use of verbally provided information (functional health literacy), perceived barriers and strategies for improving understanding during verbal exchange (for both patient and provider), and satisfaction with the relationship and healthcare information received in the clinical setting.

c. The patient perspective

Forty-nine clinic patients participated in one of six focus groups based on health literacy scores: 15 high; 13 mid and 21 low. Most were female (73%) and from minority race/ethnic groups (69% African-American, 8% Latino and 23% White). The primary themes emerging from the focus groups are presented in Table 2. The most often identified sub-themes related to the provider characteristics were communication skills and time spent with the patient. Patient sub-themes focused on their comfort with the relationship and lack of understanding (doctor provided information and more issue-specific information needed). Among those patients with low health literacy, major sub-themes were lack of understanding information provided, providers seen as poor communicators, providers don't listen, patients want more information and the primary way they get information is to ask questions of the provider. Qualitative findings confirmed the influences of both the patient and provider level characteristics in VEHL. For example, participants indicated that their previous experiences within a specific health care setting were likely to influence their willingness to exchange information with providers.

Table 2. Focus group findings representative of the Verbal Exchange Health Literacy Model constructs.

| Construct in Model | Focus Group Theme | Supporting Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics | Patient Behaviors |

|

| Relationship Characteristics | Patient-Provider Relationship |

|

| Provider/System Characteristics | Patient-Provider Communication |

|

| System Influences | Barriers and Facilitators to Care/Understanding |

|

| Patient Resources | Health Care Behavior Decisions / Navigation of Health Care System |

|

| Patient Psychosocial | Patient Characteristics, Health Care Behavior Decisions |

|

| Health Decision Behaviors | Health Care Behavior Decisions |

|

UM= University of Michigan and UAB = University of Alabama Birmingham. Level of health literacy as measured by the NVS is indicated as: 1=high group; 2=mid group; 3=low group

Phase III – Definition and Model of Verbal Exchange Health Literacy

Based on the findings from Phase I and the provider data in Phase II, we developed an initial definition and model of VEHL (not shown) which was then revised slightly to reflect the additional findings from the patient focus groups. The definition we propose for VEHL is:

The ability to speak and listen that facilitates the exchanging, understanding, and interpreting of health information for health-decision making, disease management and navigation of the healthcare system.

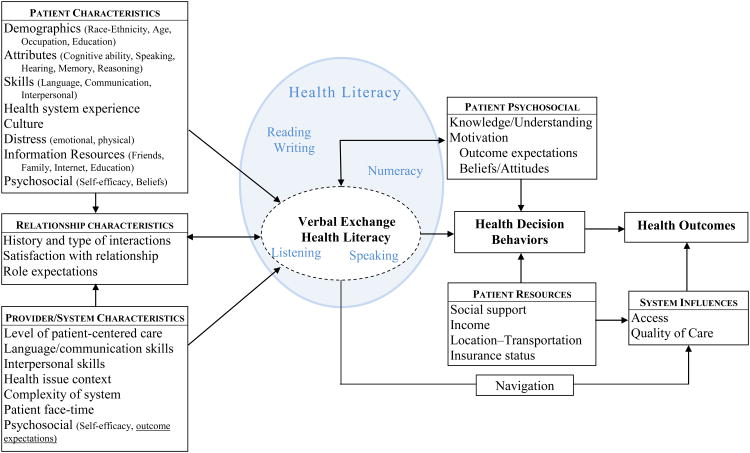

Consistent with this definition, we propose a model that depicts the impact of VEHL on health outcomes - see Figure 2.

Figure 2. Influences on Verbal Exchange Health Literacy and Health Outcomes.

4. Discussion and conclusion

4.1 Discussion

As with other definitions of health literacy, VEHL is functionally defined and context specific [68]. The proposed model has been designed to account for variability in an individual patient's VEHL based on the context, health problem, and provider. As healthcare tasks vary in difficulty by illness or preventive behavior, so does the demand required to understand and accomplish them. Further, variability in health decisions and resulting outcomes are subject to individuals' external factors.

The factors influencing VEHL include patient, provider, system and relationship characteristics which impact health outcomes [14, 66]. From the communication theories, we draw on the importance of the relationship of the communicators (patient-provider) and the content/context of the message. Patient characteristics include not only demographic descriptors, but cognitive and communication abilities. We recognize that patients have innate attributes which affect their communication and interpersonal skills, and learning of the healthcare “language.” The patient's previous personal or observed health system exposures are valuable learning experiences, similar to the experiential learning that vonWagner et al. describe [67]. Each patient enters the healthcare system with a set level of informational resources at their disposal, such as internet skills, comfort in asking questions, and friends or family in the healthcare field, as expressed by our focus group participants. These resources influence their patient experience and their VEHL.

As with other health literacy frameworks [14, 54, 58, 61, 66], the provider/system level characteristics are seen as influencing the patient's VEHL. These characteristics, which include the level of patient-centered care practiced, the provider's ability to communicate clearly using plain language and interpersonal skills, the health issue context, the complexity of the system and the amount of patient face-time, represent the “demand side” of health literacy.

Together, patient and provider characteristics influence verbal exchange as well as the relationship characteristics. The relationship between the patient and provider is based in part by past experiences with the provider (and others) and the satisfaction with the specific experience. Unlike some models that view the patient-provider interaction as influenced by health literacy, we believe this interaction influences the patient's context-specific health literacy, as the patient and provider's relationship encompasses their abilities to communicate with each other effectively and therefore the patient's ability to understand and use information for decision making. As suggested by Edwards, Davies and Edwards [58], and expressed by patients in the focus groups, both the provider's and the patient's role expectations are important. Patients enter each interaction with expectations about how much they should and need to share, how much they will participate in decision making, and what the provider's role should be. Providers also have expectations regarding provision of health information, how the particular patient should participate in their healthcare, and perhaps expectations that the patient will ask if something is not understood.

VEHL is one dimension of functional health literacy; it may be combined with reading, writing and numeracy skills in the completion of tasks related to the identification, processing and use of health information. How all these dimensions inter-relate has not been explored and is an area for future research. However, we hypothesize that these dimensions share some inter-dependency as some of the influences (e.g., education, memory) are the same and they share some common components (e.g., vocabulary, number concepts). While all dimensions of health literacy may change with time and/or experience (e.g., math education increases numeracy skills; age impacts memory of medical terms), we suggest that VEHL-related skills may be more malleable as they are influenced by every exchange within the health care system.

The patient's VEHL directly impacts the understanding and use of information exchanged between the patient and provider to make and act upon health decisions. The quality and maintenance of health decisions, including the adoption of treatments or preventive behaviors, impact health outcomes. Also influencing health decision making are patient motivation and patient resources. Our focus group participants described these factors as mediators of healthcare access and decision making rather than influences on understanding. VEHL also impacts an individual's ability to navigate the health system and access quality healthcare, as much requires speaking or listening (e.g., telephone calls to set up appointments, verbal directions within the healthcare facility).

There are several limitations to this study. There are other communication theories that could be applied to the health context, but the gain in specificity may be offset by complexity. Another limitation is that the provider interviews were conducted with a small number of pediatric providers who assessed parents, not patients, as part of a health literacy study. Therefore, their perceptions may not be representative of other types of providers. This warrants additional research, especially with primary care versus specialist physicians, as relationships may vary considerably. All participating patients were attending primary care appointments when recruited and therefore, we did not capture the perceptions of patients who attend specialty care clinics exclusively. Finally, as with any qualitative research, it is possible that personal subjective biases influenced interpretations of qualitative data. We attempted to address this by having four individuals code the focus group transcripts.

The VEHL model is specific to the aural and oral exchange of health information between patients and providers. VEHL is one of several constructs contributing to the patient's health literacy and ability to acquire and use health information as well as navigate the healthcare system. As verbal exchange is often the primary mode for sharing of health information, it is essential to explore its role in health behaviors and outcomes. Other constructs in health literacy (reading, writing and numeracy skills) combine with the VEHL to moderate health decision making and impact knowledge and conceptual understanding. In other words, acknowledgement of VEHL as factor within the total health literacy concept is essential to expanding the understanding of health literacy's impact on health outcomes.

Finally, some influences on VEHL vary by context and over time with each experience within the healthcare system as suggested by vonWagnor and Paasche-Orlow and Wolf, and with the exchange of other sources of health information (e.g., media, friends). As the patient-provider interactions and verbal exchanges with knowledgeable friends and family take place, a patient's VEHL, which may be static at any time point, continues to evolve.

4.2 Conclusion

Health literacy efforts and research focused on reading and numeracy related skills have initiated understanding of health literacy's role in health outcomes. A more robust approach requires an operational understanding of all constructs encompassed by functional health literacy. The delineation of VEHL (definition and model) proposed here is a step towards advancing this understanding. Future research should operationalize the model through use of a measure of VEHL, assessing its relationship with other dimensions of health literacy as well as its role in clinical and behavioral health outcomes, eventually leading to the design of interventions to improve VEHL for both individual and provider/system levels.

4.3 Practice Implications

Addressing the needs of individuals with inadequate health literacy to improve health outcomes may be advanced by expanding the emphasis on health literacy beyond reading, writing, and numeracy based skills to include VEHL. Increased understanding of the role of VEHL may allow more appropriate “universal precautions”; that is, facilitate better health decisions, self-management and outcomes through more effective patient-provider/system communication for all patients. This approach is consistent with the IOM's identified quality-based domain of patient-centered care [69], and will likely enhance shared decision making [32], both of which are associated with improved patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Funding Acknowledgement: The majority of this work was funded by 1R21NR01192301A1 (NINR) and some of this work was funded by R40MC8728 (HRSA-MCH)

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Kathleen F. Harrington, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama USA

Melissa A. Valerio, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, School of Public Health, San Antonio, Texas USA

References

- 1.Appleby Y, Hamilton M. Literacy as social practice: Travelling between everyday and other forms of learning. In: Crowther J, S P, editors. Lifelong Learning: Contexts and Concepts. London: 2005. edn. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nielsen-Bohlman L, Panzer AM, Kindig DA. Institute of Medicine Health Literacy: A prescription to end confusion. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ratzan SC, Parker RM, Selden CR, Zorn M, Ratzan SC, Parker RM. National Library of Medicine Current Bibliographies in Medicine: Health Literacy. Bethesda, MD: NL Pub No CBM 2000-1; National Institutes of Health, USDepartment of Health and Human Services; 2000. Introduction. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kutner M, Greenberg E, Jin Y, Paulsen C. In: The Health Literacy of America's Adults: Results From the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy. Education USDo: National Center for Education Statistics, editor. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mancuso CA, Rincon M. Impact of health literacy on longitudinal asthma outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:813–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00528.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Regan S, Viana JC, Reyen M, Rigotti NA. Prevalence and Predictors of Smoking by Inpatients During a Hospital Stay. Arch of Intern Med. 2012:1–5. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schillinger D, Grumbach K, Piette J, Wang F, Osmond D, Daher C, Palacios J, Sullivan GD, Bindman AB. Association of health literacy with diabetes outcomes. J Amer Med Assoc. 2002;288:475–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.4.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Persell SD, Osborn CY, Richard R, Skripkauskas S, Wolf MS. Limited health literacy is a barrier to medication reconciliation in ambulatory care. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1523–6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0334-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalichman SC, Ramachandran B, Catz S. Adherence to combination antiretroviral therapies in HIV patients of low health literacy. J Genl Intern Med. 1999;14:267–73. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00334.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:97–107. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeWalt DA, Hink A. Health literacy and child health outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Peds. 2009;124:S265–74. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1162B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sudore RL, Mehta KM, Simonsick EM, Harris TB, Newman AB, Satterfield S, Rosano C, Rooks RN, Rubin SM, Ayonayon HN, Yaffe K. for the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study: Limited literacy in older people and disparities in health and healthcare access. J Am Geriatric Soc. 2006;54:770–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yin HS, Johnson M, Mendelsohn AL, Abrams MA, Sanders LM, Dreyer BP. The health literacy of parents in the United States: a nationally representative study. Peds. 2009;124:S289–98. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1162E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paasche-Orlow MK, Wolf MS. The causal pathways linking health literacy to health outcomes. Am J Health Beh. 2007;31:S19–26. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2007.31.supp.S19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeWalt DA, Berkman ND, Sheridan S, Lohr KN, Pignone MP. Literacy and health outcomes - A systematic review of the literature. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:1228–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.40153.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baker DW, Gazmararian JA, Williams MV, Scott T, Parker RM, Green D, Ren JL, Peel J. Functional health literacy and the risk of hospital admission among Medicare managed care enrollees. Am J Pub Health. 2002;92:1278–83. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.8.1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baker DW, Gazmararian JA, Williams MV, Scott T, Parker RM, Green D, Ren JL, Peel J. Health literacy and use of outpatient physician services by Medicare managed care enrollees. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:215–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.21130.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baker DW, Wolf MS, Feinglass J, Thompson JA, Gazmararian JA, Huang J. Health literacy and mortality among elderly persons. Arch Int Med. 2007;167:1503–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.14.1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bryant-Stephens T. Asthma disparities in urban environments. J Allergy Clin Imm. 2009;123:1199–1206. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gold DR, Wright R. Population disparities in asthma. Ann Rev Pub Health. 2005;26:89–113. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simon PA, Zeng Z, Wold CM, Haddock W, Fielding JE. Prevalence of childhood asthma and associated morbidity in Los Angeles County: impacts of race/ethnicity and income. J Asthma. 2003;40:535–43. doi: 10.1081/jas-120018788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vernon JA, Trujillo A, Rosenbaum S, DeBuono B. Low Health Literacy: Implications for National Health Policy. Partnership for Clear Health Communications. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeWalt DA, Boone RS, Pignone MP. Literacy and its relationship with self-efficacy, trust, and participation in medical decision making. Am J Health Beh. 2007;31:S27–35. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2007.31.supp.S27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arora NK, McHorney CA. Patient preferences for medical decision making: who really wants to participate? Med Care. 2000;38:335–41. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200003000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levinson W, Kao A, Kuby A, Thisted RA. Not all patients want to participate in decision making. A national study of public preferences. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:531–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.04101.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cooper LA, Beach MC, Clever SL. Participatory decision-making in the medical encounter and its relationship to patient literacy. In: Schwartzberg J, Van Geest J, Wang C, Garzmararian J, Parker RM, Roter D, et al., editors. Understanding Health Literacy: Implications for Medicine and Public Health. Chicago, IL: AMA Press; 2004. pp. 101–18. edn. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guadagnoli E, Ward P. Patient participation in decision-making. Social Science and Medicine. 1998;47:329–39. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eckman MH, Wise R, Leonard AC, Dixon E, Burrows C, Khan F, Warm E. Impact of health literacy on outcomes and effectiveness of an educational intervention in patients with chronic diseases. Patient Educa Couns. 2012;87:143–51. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turner T, Cull WL, Bayldon B, Klass P, Sanders LM, Frintner MP, Abrams MA, Dreyer B. Pediatricians and health literacy: descriptive results from a national survey. Peds. 2009;124:S299–305. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1162F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wittich AR, Mangan J, Grad R, Wang W, Gerald LB. Pediatric asthma: caregiver health literacy and the clinician's perception. J Asthma. 2007;44:51–5. doi: 10.1080/02770900601125672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Emmons KM, Goldstein MG. Smokers who are hospitalized: a window of opportunity for cessation interventions. Prev Med. 1992;21:262–9. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(92)90024-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: Asthma prevalence, disease characteristics, and self-management education—United States, 2001-2009. MMWR Weekly. 2011;60:547–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown CJ, Peel C, Bamman MM, Allman RM. Exercise program implementation proves not feasible during acute care hospitalization. Journal of Rehabilitation and Research Development. 2006;43:939–46. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2006.04.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kessels RP. Patients' memory for medical information. J Royal Soc Med. 2003;96:219–22. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.96.5.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schillinger D, Piette J, Grumbach K, Wang F, Wilson C, Daher C, Leong-Grotz K, Castro C, Bindman AB. Closing the loop - Physician communication with diabetic patients who have low health literacy. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:83–90. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Katz MG, Jacobson TA, Veledar E, Kripalani S. Patient literacy and question-asking behavior during the medical encounter: a mixed-methods analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:782–6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0184-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koo M, Krass I, Aslani P. Enhancing patient education about medicines: factors influencing reading and seeking of written medicine information. Health Expectations. 2006;9:174–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2006.00381.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rigotti N, Munafo M, Stead L. Smoking cessation interventions for hospitalized smokers: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1950–60. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.18.1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martin LT, Schonlau M, Haas A, Derose KP, Rosenfeld L, Buka SL, Rudd R. Patient activation and advocacy: which literacy skills matter most? J Health Comm. 2011;16:177–90. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2011.604705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martin LT, Schonlau M, Haas A, Derose KP, Rudd R, Loucks EB, Rosenfeld L, Buka SL. Literacy skills and calculated 10-year risk of coronary heart disease. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:45–50. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1488-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosenfeld L, Rudd R, Emmons KM, Acevedo-Garcia D, Martin L, Buka S. Beyond reading alone: The relationship between aural literacy and asthma management. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;82:110–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weiss BD, Coyne C. Communicating with patients who cannot read. New Eng J Med. 1997;337:272–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199707243370411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Finan N. Visual literacy in images used for medical education and health promotion. J Audiovisual Media Med. 2002;25:16–23. doi: 10.1080/0140511022011837X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kennedy A, Gask L, Rogers A. Training professionals to engage with and promote self-management. Health Ed Res. 2005;20:567–78. doi: 10.1093/her/cyh018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pleasant A. Health literacy: an opportunity to improve individual, community, and global health. New Dir Adult Cont Ed. 2011;130:43–53. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hewitt-Taylor J. Use of constant comparative analysis in qualitative research. Nurs Stan. 2001;15:39–42. doi: 10.7748/ns2001.07.15.42.39.c3052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weiss BD, Mays MZ, Martz W, Castro KM, DeWalt DA, Pignone MP, Mockbee J, Hale FA. Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: the newest vital sign. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3:514–22. doi: 10.1370/afm.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Second. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roundtable on Health Literacy. Health Literacy, eHealth and Communication: Putting the Consumer First - Workshop Summary. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Institute of Medicine. Innovation in Health Literacy Research Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020. Washington D.C.; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 52.McGuire WJ. Input and Output Variables Currently Promising for Constructing Persuasive Communications. In: Ra RE, Atkin CK, editors. Public Communication Campaigns. Third. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.; 2001. pp. 22–48. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Watzlawick P, Beavin J, Jackson D. Pragmatics of Human Communication. New York: W. W. Norton; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jordan JE, Buchbinder R, Osborne RH. Conceptualising health literacy from the patient perspective. Patient Educ Coun. 2010;79:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith SK, Dixon A, Trevena L, Nutbeam D, McCaffery KJ. Exploring patient involvement in healthcare decision making across different education and functional health literacy groups. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69:1805–12. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baker DW, Gazmararian JA, Sudano J, Patterson M. The association between age and health literacy among elderly persons. J Geront - Series B. 2000;55:S368–74. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.6.s368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cutler DM, Lleras-Muney A. Education and Health: Evaluating Theories and Evidence. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Edwards M, Davies M, Edwards A. What are the external influences on information exchange and shared decision-making in healthcare consultations: a meta-synthesis of the literature. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;75:37–52. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zarcadoolas C, Pleasant A, Greer DS. Understanding health literacy: an expanded model. Health Promo Int. 2005;20:195–203. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dah609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nutbeam D. Health litearcy as a public health goal: a challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promo Int. 2000;15:259–67. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Parker RM. Institute of Medicine workshop on Measures of Health Literacy: 26 February 2009. Washington D.C.; 2009. Measuring health literacy: What? So What? Now What? [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nutbeam D. The evolving concept of health literacy. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67:2072–8. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Roter DL, Erby L, Larson S, Ellington L. Oral literacy demand of prenatal genetic counseling dialogue: Predictors of learning. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;75:392–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Roter DL, Erby LH, Larson S, Ellington L. Assessing oral literacy demand in genetic counseling dialogue: preliminary test of a conceptual framework. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65:1442–57. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Roter DL. Oral literacy demand of health care communication: challenges and solutions. Nurs Outlook. 2011;59:79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Baker DW. The meaning and the measure of health literacy. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:878–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00540.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.von Wagner C, Steptoe A, Wolf MS, Wardle J. Health Literacy and health actions: a review and a framework from health psychology. Health Ed Beh. 2009;36:860–877. doi: 10.1177/1090198108322819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nutbeam D. Defining and measuring health literacy: what can we learn from literacy studies? Int J Pub Health. 2009;54:303–5. doi: 10.1007/s00038-009-0050-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]