Abstract

The evolutionarily conserved Hippo signaling pathway controls organ size by regulating cell proliferation and apoptosis and this process involves Yap1. The zebrafish Yap1 acts during neural differentiation, but its function is not fully understood. The detailed analysis of yap1 expression in proliferative regions, revealed it in the otic placode that gives rise to the lateral line system affected by the morpholino-mediated knockdown of Yap1. The comparative microarray analysis of transcriptome of Yap1-deficient embryos demonstrated changes in expression of many genes, including the Wnt signaling pathway and, in particular, prox1a known for its role in development of mechanoreceptors in the lateral line. The knockdown of Yap1 causes a deficiency of differentiation of mechanoreceptors, and this defect can be rescued by prox1a mRNA. Our studies revealed a role of Yap1 in regulation of Wnt signaling pathway and its target Prox1a during differentiation of mechanosensory cells.

The Hippo signaling pathway is evolutionarily conserved from fly to human. It controls organ size by regulating cell proliferation and apoptosis1,2. Recent studies linked this pathway with regulation of cell proliferation in the CNS3,4. An important role in the Hippo pathway is performed by Yes-Associated Protein 65 (Yap), the transcription regulator containing the binding domain and transactivation domain. Yap was discovered as 65 KDa protein binding to Src homology domain (SH3) of the Yes protein5. Homologs of Yap have since been discovered in Drosophila (Yorkie)6, human and mouse (YAP1)7, zebrafish (yap1)8, Xenopus9. YAP functions to regulate cell proliferation, growth and survival1,6,10,11. Recently YAP was found to act as a nuclear relay of mechanical signals exerted by ECM rigidity and cell shape. This regulation requires Rho GTPase activity and tension of the actomyosin cytoskeleton, but is independent of the Hippo cascade. Within this context YAP/TAZ activity was promoted by overexpression of activated Diaphanous causing F-actin polymerization and stress fibres formation12,13. The zebrafish Yap1 has been shown to play a role during the development of the brain, eyes, and neural crest8.

The lateral line system is a specialized sensory organ of aquatic animals for detection of changes in hydrodynamic pressure. It consists of neuromasts arranged in a particular pattern on the body surface. Each neuromast represents a central rosette of mechanosensory hair cells surrounded by mantle cells and support cells. The mechanoreceptors are functionally and morphologically related to the mechanoreceptors of the inner ear and functionally the lateral line organ is linked to the inner ear too. The lateral line system develops in result of collective cell migration of several lateral line primordia, where early events of cell differentiation and neuromast morphogenesis are taking place14,15,16,17. Another example of collective cell migration is studied in Drosophila border cells during oogenesis. Here the Hippo signaling pathway was found to be involved in regulation of interaction of determinants of cell polarity resulting in polarization of the actin cytoskeleton18.

The developmental events regulating the specification of mechanoreceptors remain not fully understood. Several signaling pathways were implicated in this process, including, but not limited to the chemokine, Wnt, Fgf and Notch14,19,20,21,22,23. These pathways induce an expression of bHLH transcription factor Atoh1 in committed precursors each of which divides in a process regulated by Atp2b1a that gives rise to a pair of mechanoreceptors15,24. Prospero-related homeobox gene 1 (Prox1a) is a transcription factor; depending on the target gene it acts as a transcription activator or repressor. Regulation of cell cycle and cell fate specification in several types of tissue, including pancreas, lens and adrenal gland requires Prox1a25,26,27. In the chick spinal cord Prox1 drives neuronal precursors out of the cell cycle to initiate expression of neuronal proteins during differentiation of interneurons28. Importantly, Prox1a is expressed in the lateral line primordium. It is necessary for mechanoreceptors in the zebrafish lateral line to differentiate and acquire functionality29,30.

The recent discovery of the GPCR-mediated signaling acting upstream of the Hippo-Yap pathway is important within a context of the lateral line development. It was found that Gi proteins linked to SDF1-CXCR4 axis act as moderate activators of Yap, whereas G12, G13 proteins linked to SDF-1 induced migration through Cxcr4 and sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) signals act as strong activators of Yap31,32. Given a role of S1P as an enhancer of the CXCR4-dependent effects induced by SDF1 in other contexts33, the net effect of Yap activation, controlled by GPCRs at different levels, could be to promote migration of the lateral line primordium. This suggested a role of Hippo-Yap pathway in development of the lateral line system in teleosts.

With this notion in mind, we analyzed the late expression pattern of yap1 and demonstrated that this gene is highly expressed in proliferative regions, including the otic placode that gives rise to the ear vesicle and lateral line system. The morpholino-mediated knockdown (KD) of Yap1 affects development of the lateral line system in developing zebrafish. The comparative microarray analysis of transcriptome of zebrafish embryos deficient in Yap1 demonstrated that this protein regulates expression of many genes, including prox1a linked to differentiation of mechanosensory cells. The knockdown of Yap1 recapitulates the Prox1a deficiency in neuromast mechanosensory cells, which could be rescued by prox1a mRNA. Thus, our studies revealed a novel function of Yap1 in regulation of Prox1a, which in turn regulates terminal differentiation of mechanosensory cells.

Results

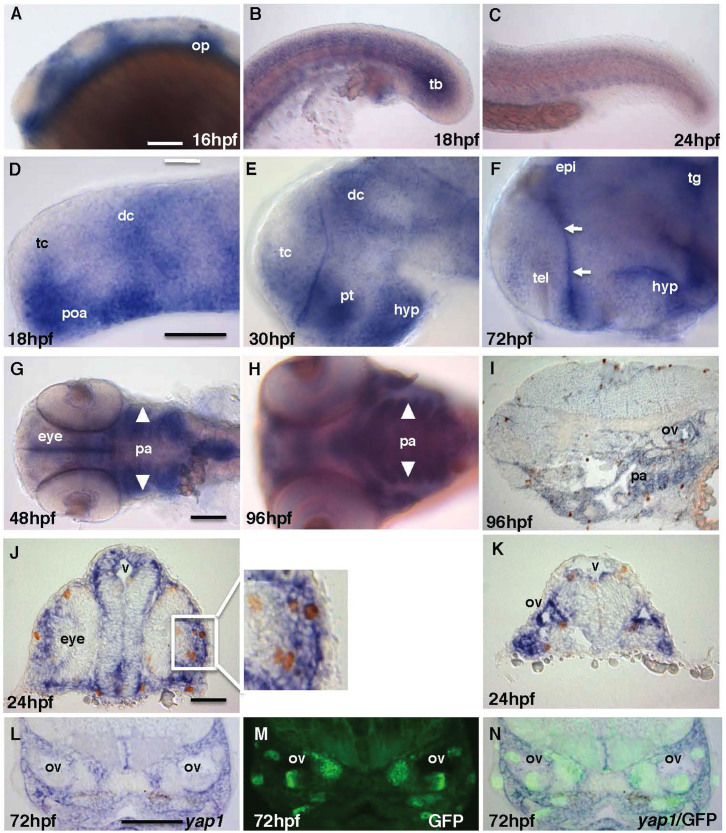

Zebrafish yap1 is expressed in proliferative regions during embryonic development

Previous study demonstrated that in zebrafish yap1 transcripts are of maternal origin, but in later embryos they were detected in the notochord, brain, eyes, pharyngeal arches, and pectoral fins8. Here we focused on a role of Yap1 during late neural development. Therefore a distribution of yap1 transcripts in the CNS during development up to 96 hpf was analyzed. Indeed, early on, yap1 is expressed ubiquitously (not shown), but later its expression becomes restricted to the proliferative regions, including the ventricular zone of the neural tube (Figure 1A, D–F), pectoral fin (30 hpf onwards, not shown), and pharyngeal arches (16 hpf onwards, Figure 1G–I). Most mitotic cells with phospho-histone 3 (ph3)-positive nuclei were found within yap1 expression domains (Figure 1I–K). It is important in the context of this paper to note that yap1 was also expressed in the tail bud mesoderm and somites (Figure 1B, C). This analysis of the expression pattern suggests that Yap1 plays a role in cell proliferation.

Figure 1. Zebrafish yap1 is highly expressed in regions with active cell proliferation and in particular sensory progenitor cells of the inner ear.

(A–C) yap1 is expressed in the brain, somites and tail bud until mid-somitogenesis and its expression in the posterior body declines later on. (D–F) yap1 expression become more restricted to the ventricular zones (proliferative region, arrows) in the brain as the embryo matures. (G–I) Staining of yap1 in pharyngeal arch (arrowhead) at 48–96 hpf. (J), (K) Most proliferative cells detected by anti-pH3 antibody (brown, cell nucleus) are yap1-positive (blue) in cross-section of 24 hpf and (I) sagittal-section of 96 hpf embryos. L-N – cross-sections at the mid-hindbrain (ear) level of 72 hpf SqET33-mi60A transgenic larvae (lnfg, progenitors of sensory cells). (L) yap1 in situ hybridization; (M) GFP expression; (N) composite yap1 in situ hybridization/GFP expression. (A–F) – lateral view, (G), (H) – ventral view. Scale bar = 40 μm. Abbreviations: dc, diencephalon; epi, epiphysis; hyp, hypothalamus; op, otic placode; pa, pharyngeal arches; poa, preoptic area; pt, prethalamus; tb, tail bud; tc, telencephalon; tg, tegmentum.

Yap1 knockdown affects the lateral line

To understand the function of Yap1 in zebrafish early neurodevelopment, we injected translational and splice-site MO against the 5′-untranslated region (5′UTR) and exon1-intron1 (E1I1) splice site at 1 to 2-cell stage and analyzed changes in Yap1 expression, general morphology of morphants, cell proliferation and apoptosis. We also studied morphant transcriptome using microarray. Both yap1 MOs elicited similar phenotype characterized by delayed development, reduced head and eyes, cardiac edema, and curved trunk (Figure S1B, S1D). 5′UTR MO elicited more severe phenotype probably due to its effect on maternal transcripts of Yap1. The effect of E1I1 MO has been rescued by co-injection of yap1 mRNA (Figure S1F, S2). Thus the follow-up analysis of Yap1 loss-of-function (LOF) was done in E1I1 morphants. RT-PCR of yap1 morphant total RNA showed a reduction of the band corresponding to the yap1 transcript and appearance of a minor band (Figure S1G). This indicated that the E1I1 MO-mediated block of a splice-site generated an abnormally spliced and unstable yap1 mRNA that contributed to the partial LOF of Yap1. Interestingly, the gain-of-function (GOF) experiment by overexpression of yap1 mRNA did not cause any obvious phenotype (Figure S1E, S2A, C). An injection of the anti-Yap1 MO caused extensive apoptosis, which was efficiently rescued by yap1 mRNA (Fig. S2A). The effect of MO was transient and by 48 hpf, when the lateral line primordium (Prim1) completed its migration to the tail bud and primary neuromasts were formed, the level of cell death in the posterior lateral line was similar to that in controls (Figure S2B). At gross morphological level cell proliferation was not significantly affected in both LOF and GOF of Yap1 (Figure S2C); this observation correlates with a lack of excessive growth of embryos upon Yap1 overexpression and suggests that Yap1 acts as a permissive regulator of embryo growth during development.

To understand molecular events downstream of Yap1 we used the microarray analysis to compare gene expression in controls versus Yap1 morphants. This analysis demonstrated changes in expression of genes in the p53 and Wnt signaling (Figure S3 and not shown; Supplementary Table 1). Changes in the p53 signaling network is the likely cause of the observed apoptotic phenotype. A role of Yap1 in the Hippo pathway has been studied largely within a context of cell proliferation, but little is known about its role in regulation of genes involved in cell differentiation and specification. According to information in the Zebrafish Information Network (ZFIN) some of the genes down-regulated in Yap1 morphants were associated with detection and processing of sensory information in the eye, ear, cranial ganglia, optic tectum and ear (ccng2, crx, fhl2b, icat, isl1, lnx2, pnp4a, ptpra, rbpms2, rufy3, tomm34, vsx1). Several other genes are known to be expressed in the ear and lateral line system, including myo1bl2, ndrg4, prox1a, ptena, sema3aa.

Prox1a acts downstream of Yap1

Prox1a is a target of β-catenin-TCF/LEF signaling in the mammalian hippocampus and zebrafish eye and liver34,35,36. It is expressed in the lateral line primordium29 playing a role in differentiation of mechanosensory cells30. Hence we decided to do more detailed analysis of its expression in yap1 morphants. In order to avoid the non-specific effects due to apoptosis in Yap1 morphants, all follow-up experiments were performed in presence of anti-p53 MO.

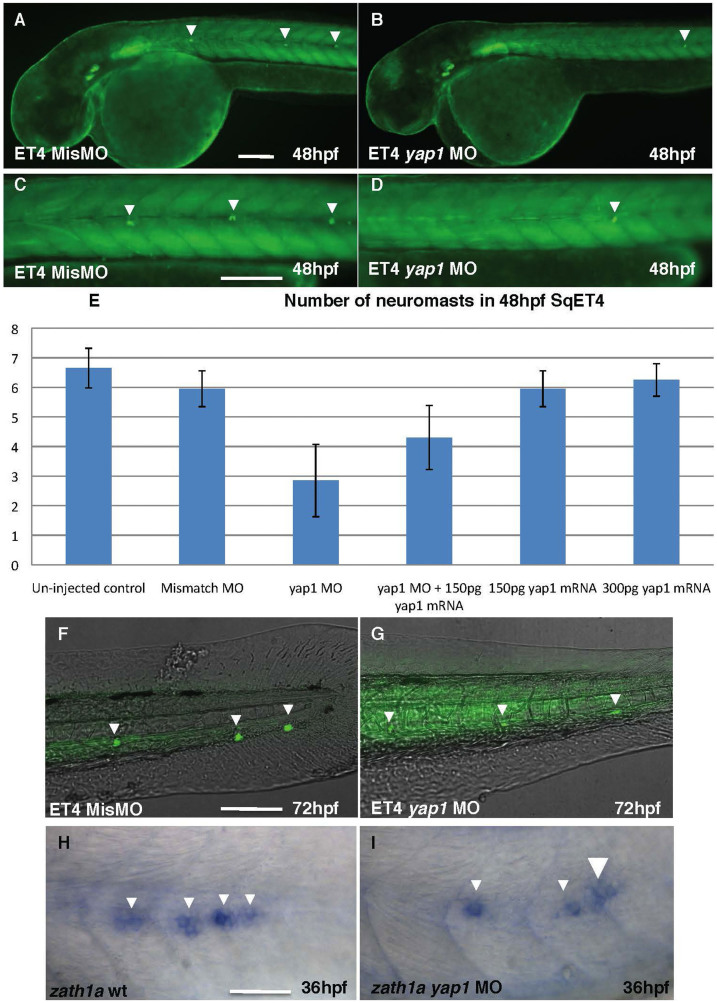

SqET4 trangenics express GFP in mechanosensory cells of the lateral line24. MO-mediated Yap1 LOF caused a reduction in a number of neuromasts of SqET4 larvae (Figure 2B, D), in absence of such effect of the mismatch MO (Figure 2A, C). This defect was rescued in a dose-dependent manner by coinjection of MO and yap1 mRNA. At 48 hpf both wild type control and mismatch control SqET4 embryos developed six or more neuromasts in the lateral line on each side of the trunk, whereas in Yap1 morphants only three neuromasts were detected (Figure 2E, Table 1). By 72 hpf neuromasts were detected in the tail of morphants, but GFP expression in neuromasts was significantly reduced (Figure 2F, G). This also correlated with a reduction in expression of zath1a in the primordium (PrimI; Figure 2H, I).

Figure 2. The number of neuromasts is reduced in yap1 SqET4 morphants.

(A), (C), (F) – controls; (B), (D), (G) – Yap1 morphants. All embryos are shown in lateral view. The table illustrates the rescue effect of yap1 mRNA coinjection. The original data are provided as a supplement. (A), (B) – head and anterior trunk, (C), (D) – intermediate trunk, (F), (G) – tail. Notice a reduction in a number of neuromast cells and increase of background due to longer exposure in (G) comparing to (F). (H), (I) – zath1a expression in the lateral line primordium of controls (H) and morphants (I). Scale bar = 40 μm, (H)&(J) = 20 μm.

Table 1. The number of neuromasts is reduced in yap1 SqET4 morphants.

| Embryos | Number of neuromasts | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 48 hpf control | Un-injected control | Mismatch MO | yap1 MO | yap1 MO + 150 pg yap1 mRNA | 150 pg yap1 mRNA | 300 pg yap1 mRNA |

| 1 | 6 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 6 |

| 2 | 7 | 7 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 6 |

| 3 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 6 |

| 4 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 5 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 7 |

| 6 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 6 |

| 7 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 6 |

| 8 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 7 |

| 9 | 7 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 10 | 7 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 6 |

| 11 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 |

| 12 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 |

| 13 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| 14 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 5 |

| 15 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| 16 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 |

| 17 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 18 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 7 |

| 19 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 |

| 20 | 7 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Average | 6.65 ± 0.67 | 5.95 ± 0.60 | 2.85 ± 1.22 | 4.3 ± 1.08 | 5.95 ± 0.60 | 6.25 ± 0.55 |

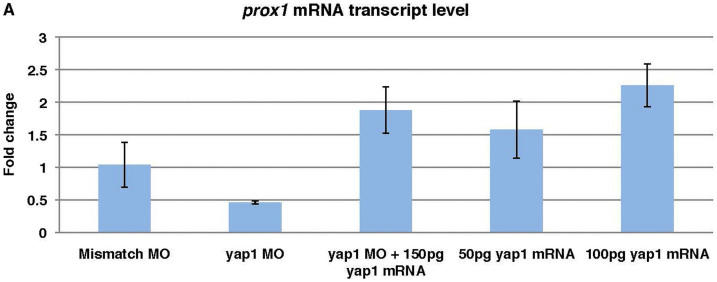

Quantitative PCR showed that the transcript level of prox1a in the mismatch MO control is similar to that in the un-injected control, while that in yap1 morphants was reduced below 50%. yap1 mRNA injection into yap1 morphants caused an increase in prox1a transcripts, whereas in the yap1 GOF experiment prox1a transcription increased in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 3). Thus we decided to explore this phenomenon in more detail.

Figure 3. prox1a transcript level is yap1-dose-dependent.

Taking un-injected control as 1 fold change, reduced prox1a expression level in yap1 morphants could be rescued with yap1 mRNA. Higher doses of yap1 mRNA led to elevated prox1a expression. Mismatch control embryos showed no significant deviation from un-injected controls. Quantitative PCR results from yap1 morphants, rescued morphants and yap1 gain-of-function were calculated with delta CT method for fold change. The significant difference of the fold change, as compared to control with assumed fold change of one, was analyzed with two-tailed t-test.

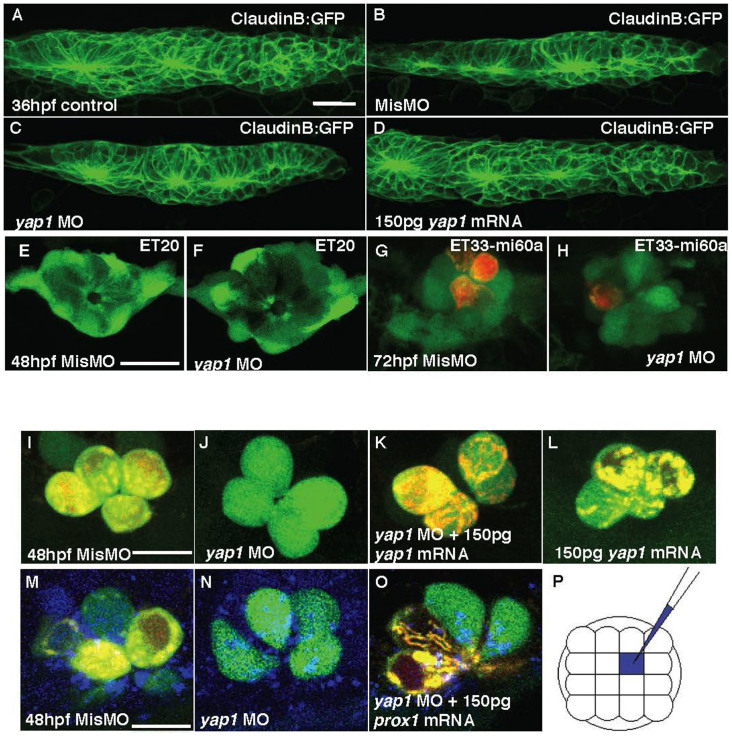

A number of neuromasts in yap1 morphants was reduced even despite correction for developmental stage difference between controls and morphants. This defect in yap1 morphants was completely rescued by yap1 mRNA (Table 1), whereas overexpression of yap1 did not increase a number of neuromasts (data not shown). Several reasons may cause a reduction of neuromasts, including, but not limited to, the reduction of the primordium proper, its abnormal migration, failure of neuromast deposition, and defective differentiation of hair cells. To find which of these may play a role here, yap1 MO was injected into the claudinB:GFP transgenics, where all cells of PrimI are labeled by GFP37. Characterization of PrimI in morphants at 36 hpf demonstrated a reduction of size of PrimI by 28% comparing to 12% reduction in the mismatch control embryos and 9% reduction upon GOF, where the two latter values probably reflect effect of microinjection (Table 2;Figure 4A–D). Similar, the otic vesicle of morphants appears somewhat reduced, but its patterning seems to be not affected (Figure S4A–C).

Table 2. PrimI volume (μm3).

| 36 hpf embryos | Un-injected control | Mismatch MO | yap1 MO | 150 pg yap1 mRNA overexpression |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 93951.70 | 85101.09 | 66624.06 | 83936.00 |

| 2 | 91343.15 | 85275.50 | 53287.04 | 96432.14 |

| 3 | 90352.86 | 83684.40 | 69950.38 | 76964.15 |

| 4 | 80658.73 | 72548.66 | 65498.25 | 78275.99 |

| 5 | 83206.31 | 85557.68 | 51501.79 | 75647.91 |

| 6 | 110148.70 | 71752.63 | 76168.50 | 76688.70 |

| 7 | 97783.95 | 72515.25 | 87276.48 | 79408.34 |

| 8 | 86273.50 | 82327.12 | 29689.07 | 81211.77 |

| 9 | 81884.88 | 76362.45 | 83427.23 | 88952.49 |

| Average | 90622.64 ± 9312.42 | 79458.308 ± 6060.98 | 64824.76 ± 17867.26 | 81946.39 ± 6850.83 |

Volume of PrimI at 36 hpf measured in μm3 was more significantly affected in LOF of yap1 (n = 9).

Figure 4. The primordium, neuromasts and mechanoreceptors of the lateral line in yap1 morphants.

(A–D) Primordium I (PrimI) in yap1 morphants. (E) Size of PrimI at 36 hpf. (E, F) Mantle cells of neuromast in 72 hpf ET20 yap1 morphants. (G–H) Mechanoreceptors of neuromast (red, DiAsp) in 72 hpf ET33-mi60a embryos, support cells (green). (I–L) hair cells. (J–L) Loss of yap1 abolished the functionality of hair cells in SqET4 transgenics, stained with DiAsp (red); it was rescued with yap1 mRNA injection. (M–O) Mismatch MO, yap1 MO or yap1 MO with prox1 mRNA were co-injected with a marker (Cascade Blue) into single cell of SqET4 embryos at 16-cell stage. (P) The schematic drawing of injected single cell (blue), any one of the middle four cells, at 16-cell stage. Scale bar = 10 μm.

To identify specific cells of neuromast affected by yap1 LOF, the transgenic zebrafish lines with GFP expression in the mantle (SqET20), support (SqET33-mi60a), and hair cells (SqET4) were utilised24,38,39. Functional hair cells were also stained with the viable DiAsp dye to check whether terminal differentiation of hair cells was affected by yap1 knockdown. This analysis showed that in morphants the support and mantle cells appeared relatively normal (Figure 4E–H), but the functional DiAsp-positive hair cells were reduced (Figure 4G–J).

In the L1 neuromast at 48 hpf (Figure 4I), 70% of hair cells were terminally differentiated and functional in mismatch control morphants similar to that in the wild type controls (61.83%, Table 3), but in the yap1 morphants they were reduced in a dose-dependent manner upon injection of 0.05 pmol (52.5%) and 0.1 pmol morpholino (13.33%; Figure 4J, Table 3). Moreover, hair cells functionality increased in a dose-dependent manner to 22.3%, when 0.1 pmol yap1 MO was co-injected with 75 pg of yap1 mRNA, and to 65%, when a dose of yap1 mRNA increased to 150 pg (Figure 4K). There was no significant difference in a number of functional hair cells (63.5%; Table 3) and neuromasts (Table 1) between controls and Yap1-overexpressing embryos (Figure 4L).

Table 3. Percentage of functional hair cells in L1 neuromast (%).

| 48 hpf Embryos | Un-injected control | Mismatch MO | 0.1 pmol yap1 MO | 0.05 pmol yap1 MO | yap1 MO + 75 pg yap1 mRNA | yap1 MO + 150 pg yap1 mRNA | 150 pg yap1 mRNA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4/6 (66.67%) | 4/6 (66.67%) | 0/4 (0%) | 3/4 (75.00%) | 1/3 (33.33%) | 1/2 (50.00%) | 2/6 (33.33%) |

| 2 | 2/4 (50.0%) | 2/4 (50.0%) | 1/3 (33.33%) | 3/6 (50.0%) | 0/2 (0%) | 2/4 (50.0%) | 3/5 (60.0%) |

| 3 | 4/6 (66.67%) | 2/4 (50.0%) | 0/2 (0%) | 2/4 (50.0%) | 1/2 (50.0%) | 2/4 (50.0%) | 2/2 (100.0%) |

| 4 | 1/2 (50.0%) | 3/3 (100%) | 1/3 (33.33%) | 2/4 (50.0%) | 2/5 (40.0%) | 2/4 (50.0%) | 2/4 (50.0%) |

| 5 | 3/5 (60.0%) | 2/3 (66.67%) | 0/3 (0%) | 3/3 (100.0%) | 2/3 (66.67%) | 2/3 (66.67%) | 2/3 (66.67%) |

| 6 | 3/4 (75.00%) | 3/3 (100.0%) | 0/2 (0%) | 0/2 (0%) | 0/2 (0%) | 4/4 (100.0%) | 4/4 (100.0%) |

| 7 | 2/4 (50.0%) | 3/3 (100.0%) | 0/2 (0%) | 2/4 (50.0%) | 0/1 (0%) | 4/6 (66.67%) | 3/6 (50.0%) |

| 8 | 3/6 (50.0%) | 2/4 (50.0%) | 1/3 (33.33%) | 2/4 (50.0%) | 0/1 (0%) | 1/2 (50.0%) | 2/4 (50.0%) |

| 9 | 2/2 100 | 2/4 (50.0%) | 1/3 (33.33%) | 2/4 (50.0%) | 1/3 (33.33%) | 2/2 (100.0%) | 3/4 (75.00%) |

| 10 | 2/4 (50.0%) | 2/3 (66.67%) | 0/2 (0%) | 2/4 (50.0%) | 0/3 (0%) | 2/3 (66.67%) | 2/4 (50.0%) |

| Average % | 61.83 ± 16.2 | 70 ± 21.9 | 13.33 ± 17.2 | 52.5 ± 24.8 | 22.33 ± 25.3 | 65 ± 18.9 | 63.5 ± 22.2 |

To investigate whether prox1a manipulation could rescue the phenotype of yap1 morphants, prox1a mRNA was co-injected with yap1 MO into 1–2 cell stage embryos. In this setup of global inhibition of Yap1 and overexpression of Prox1a, prox1a mRNA failed to rescue global morphology of Yap1 morphants (data not shown). This was expected since comparing to Yap1, Prox1a is expressed in more restricted manner. This suggests that Prox1a probably functions downstream of Yap1 only in some cells. To focus on interaction of these two genes in the lateral line system, prox1a mRNA was co-injected with yap1 MO into one of the middle four cells fated to adopt ectoderm fate of the 16-cell stage SqET4 embryos (Figure 4M–O24,40). Cascade blue dye was added into the injection mixture as tracing dye to identify hair cells derived from injected blastomere. 77.74% hair cells in L1 neuromast were functional in mismatch morphants. In contrast, only 21.07% hair cells were functional in Yap1 morphants. Upon prox1a mRNA co-injection this number increased (69.6%, Table 4). This evidence strongly supported an idea that yap1 acts not only during proliferation of mechanoreceptors in the lateral line system, but it also acts to regulate their terminal differentiation of these cells acting upstream of prox1a.

Table 4. Percentage of functional hair cells in L1 neuromast (%).

| 48 hpf embryos | Mismatch MO | yap1 MO | yap1 MO + 150 pg prox1 mRNA |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2/2 (100.0%) | 0/2 (0%) | 4/6 (66.67%) |

| 2 | 2/3 (66.67%) | 0/2 (0%) | 5/6 (83.33%) |

| 3 | 4/5 (80.0%) | 2/4 (50.0%) | 4/6 (66.67%) |

| 4 | 3/4 (75.0%) | 0/4 (0%) | 3/4 (75.0%) |

| 5 | 2/4 (50.0%) | 0/2 (0%) | 3/4 (75.0%) |

| 6 | 2/4 (100.0%) | 1/2 (50.0%) | 2/4 (50.0%) |

| 7 | 2/2 (50.0%) | 1/2 (50.0%) | 4/4 (100.0%) |

| 8 | 4/4 (100.0%) | 0/2 0(0%) | 4/4 (100.0%) |

| 9 | 2/4 (50.0%) | 0/2 (0%) | 2/4 (50.0%) |

| 10 | 3/3 (100.0%) | 1/2 (50.0%) | 4/6 (66.67%) |

| 11 | 4/4 (100.0%) | 2/4 (50.0%) | 2/4 (50.0%) |

| 12 | 3/4 (75.0%) | 1/4 (25.0% | 4/6 (66.67%) |

| 13 | 4/6 (66.67%) | 2/4 (50.0%) | 2/2 (100.0%) |

| 14 | 4/6 (66.67%) | 1/3 (33.33%) | 4/6 (66.67%) |

| 15 | 2/3 (66.67%) | 0/2 (0%) | 2/4 (50.0%) |

| 16 | 3/4 (75.0%) | 0/4 (0%) | 3/6 (50.0%) |

| 17 | 4/4 (100.0%) | 0/4 (0%) | 4/6 (66.67%) |

| Average % | 77.75 ± 18.5 | 21.07 ± 23.2 | 69.6 ± 17.1 |

Discussion

Zebrafish yap1 is essential for maintenance of progenitors

The fact that yap1 is expressed in proliferative regions reaffirms its role in survival of progenitor cells in other animal models such as chick3,4. Yap1 may regulate cell proliferation differentially not only due to a high level of expression in the proliferative region. It may act later on in different proliferative regions and through multiple downstream targets many of which belong to the Wnt signalling pathway as shown by microarray analysis presented here. For example, yap1 is expressed in pharyngeal arches from 16 hpf onwards while in somites it expression is limited by the 10–30 hpf window. Thus yap1 probably plays an important role in regulation of cell proliferation, which is well coordinated in space and time.

The knockdown of yap1 in zebrafish embryos reported here causes the reduction of the head, eyes and defective axis elongation in a mode similar to that observed with Yap1/yorkie LOF in Drosophila6, Xenopus9 and zebrafish8. This suggested that Yap1 function is conserved in evolution. The phenotype observed is also suggestive of a role of yap1 in cell survival, as shown by an increase in cell death in yap1 morphants. This phenotype may arise also due to reduced cell proliferation (Table 2, Figure 4C). In particular, yap1 is essential for neural development as demonstrated by expression of this gene in regions containing neural progenitors in human fetal and adult brain41. Little cell death observed in the trunk of zebrafish at 48 hpf indicated that neuromast reduction was not due to an apoptosis in the lateral line system or surrounding tissue. Alternatively, it could be due to a role of Yap1 in cell proliferation during early development of the lateral line, which correlates with its expression in the posterior placodal area. The initial size of the primordium of the lateral line defines a number of neuromasts it generates42. Hence Yap1 expression in the proliferative cells of otic placode and a reduction of the PrimI volume in Yap1 morphants support a role of Yap1 in cell proliferation during development of the lateral line.

The two morpholino used in this study caused changes in expression of a number of genes including prox1a, but there were some genes which expression was affected by only one of these two morpholino. This indicates a possibility of differential splicing of yap1. Whereas in zebrafish so far only one yap1 copy and only one isoform have been predicted, in other species this gene is either duplicated or expressed as a number of protein-coding isoforms, processed transcripts and mRNA containing introns. For example, in human nine YAP1 isoforms were predicted, in mice 10 isoforms and in fugu five, one of which lacks exon 143,44. At the same time, the number of exons of Yap1 annotated, which often is well conserved in evolution, varies between eight (zebrafish, stickleback, tetraodon, and tilapia), nine (fugu, cod, coelacanth, medaka) and 10 (mouse and human). The mammalian gene contains two tiny exons, one of which may have been left unnoticed so far in teleosts. This warrants further study of complexity of yap1 transcripts in zebrafish, where their specific functions could be addressed by morpholino-mediated knockdown of specific transcripts.

It has been shown that yap1 expression is activated during cancer development45. Overexpression of yap1 in embryonic zebrafish neither caused tumor formation nor led to excessive proliferation and overgrowth of organ size reported in other model animals10. Increase of yap1 mRNA dose up to 750 pg per embryo only increased mortality and caused non-specific developmental defects, with LD50 at 300 pg. Similarly, an injection of mRNA of the constitutively active (Ser-87-Ala) Yap1 produced similar outcome (data not shown). While this indicates that a scenario that plays in developing zebrafish upon Yap1 GOF could be different from that in Drosophila development or human carcinogenesis, the nature of a transient experiment used here could be the main reason of absence of significant tissue overgrowth and/or tumor formation.

Yap1 and mechanoreceptors

prox1a acts downstream of the canonical Wnt signaling34. Prox1a has been previously linked to terminal differentiation and functionality of hair cells in lateral line neuromasts as detected by the marker of mitochondrial activity DiAsp30. Since we found that prox1a is a downstream target of yap1 and yap1 knockdown phenocopies prox1a LOF, we investigated whether yap1 influences hair cell functionality through prox1a. Similar to prox1a GOF, yap1 overexpression did not cause an increase in the neuromast number and/or increased functionality of mechanoreceptors (Figure 5). In yap1 morphants prox1a rescues a number of characteristics in the lateral line resulting in improved functionality of mechanoreceptors. This supported an idea that yap1 acts in an epistatic manner upstream of prox1a. The cranial placodes are specialized areas of embryonic ectoderm giving rise to many sensory organs and neural ganglia of the vertebrate head. Of the seven cranial placodes, the epibranchial, otic and lateral line placodes originate from the posterior placodal area, where each placode is specified in response to additional signals41. yap1 is expressed in the posterior placodal area giving rise to the lateral line and several other lineages (Figure 1). This suggests a potential functional link between yap1 and prox1a in the posterior placodal area, where prox1a is also expressed30. Since yap1 expression is absent in the primordium of the posterior lateral line and mechanosensory cell differentiation in otic vesicles was unaffected in yap1 morphants, the regulatory interaction involving yap1 and prox1a is probably indirect and may take place during development of the posterior placodal area and specification of the lateral line placode. Given the fact that Yap1 regulates a number of genes in the Wnt signaling pathway (Figure S3), an activity of this pathway well-known for its role in the lateral line development may mediate an effect of Yap1 on Prox1a23,34.

Being developed initially as a cationic mitochondrial dye DiAsp is used also to evaluate functionality of mechanosensory hair cells46. Since mitochondria/ATP-dependent PrimI migration is relatively normal, it does not look like that mitochondria were strongly affected by yap1 knockdown. And yet the microarray analysis revealed a down-regulation of the gene tomm34 encoding a translocase of the outer mitochondrial membrane subunit 3447. This provided a potential explanation for the deficient maturation of Prox1a-deficient mechanosensory cells evaluated by the mitochondrial dye DiAsp30. Since Tomm34 could be one of the most downstream components of the signaling cascade involved here, its link to Yap1-Prox1a could be studied further.

Although yap1 is largely known as a part of Hippo pathway, which is a subject of intense studies in cell proliferation, survival, and apoptosis, the function of yap1 in development of mechanoreceptors have not been addressed so far. Here we found and analyzed the link between yap1 that acts in cell proliferation and prox1a that acts to initiate cell differentiation within a context of complex interactions taking place during regulation of terminal differentiation of mechanoreceptors. These may involve the linear pathway including Yap1-canonical Wnt-Prox1a-Tomm34. Recently, it was shown that during collective migration of border cells in Drosophila oogenesis Yorkie/Yap acts independently of Hippo pathway18. Further studies are required to clarify a role of upstream regulation of Yap1 in the lateral line development.

Methods

Zebrafish maintenance and manipulation

The experiments using the wild type AB strain and transgenic lines SqET4, SqET20, SqET33-mi60A24,39 and Tg(claudinB-GFP)37 of zebrafish (Danio rerio) were carried on according to the permission of the Biopolis institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) approving the experiments (application #090430) and regulations of the IMCB Fish Facility. Pigmentation was prevented in 24 hpf and older embryos with 0.2 mM 1-phenyl-2-thiourea (PTU), and selected embryos were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde-phosphate buffed saline (PFA-PBS) at desired development stages48.

Morpholino and synthetic mRNA injection

yap1 antisense morpholinos (MO) were designed and synthesized by Gene Tools LLC (Corvallis, USA) to target translational start site (5′UTR) and splice site (E1I1). Sequence of MOs were as follows: 5′UTR MO, 5′-ACTGAAACCGTTTTCAAGGAAAGTC-3′; E1I1 MO, 5′-GGTGGTCTCTTACTTGTCTGGAGTG-3′; 5-base-pair mismatch MO designed against E1I1 MO, 5′-GGTGCTCTGTTACTTCTCAGCAGTG-3′. The MOs were reconstituted to 1 mM with sterile water and diluted with Danieu's solution for working solution. The injected volume was 1 nL per embryo of 0.1 pmol and 0.125 pmol for mismatch/E1I1 MO and 5′UTR MO respectively at 1 to 2-cell stage. All embryos were co-injected with p53 MO at 1.5 fold of E1I1 MO or 5′UTR MO to reduce off-target neural death. Where necessary the developmental stage of morphants was adjusted to compensate for a developmental delay. yap1 mRNA and prox1a mRNA were synthesized according to mMessage mMachine protocol (Ambion, USA). Embryos were injected with yap1 mRNA encoding stabilized versions of Yap1 - T259G (S → A) and T262G (S → A). 16-cell stage injection was achieved by placing the embryo in Petri dish with moulded agar (1.5% agarose in egg water) injection wells and injecting one of the middle four blastomeres with 200 pl of working solution24. Cascade blue (D-1976, Invitrogen, USA) was added as tracer. To identify ectodermal derived cells that would eventually give rise to lateral line system, embryos with defined cone-shaped region of fluorescently labelled cells at 4 hpf were allowed to develop further for analysis.

Hair cells vital staining

Mature hair cells in neuromast were labelled red by immersing live embryos in 5 mM DiAsp (4-(4-Diethylaminostyryl)-1-methylpyridinium iodide) (D3418, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) for 5 min and rinsed with egg water prior to 0.2% tricaine treatment and fluorescent imaging.

Whole-mount in situ hybridization, immunohistochemistry, and cryosectioning

Probes were synthesized with either digoxigenin-labeled or fluorescine-labeled RNA antisense oligonucleotides (Roche, USA). WISH was performed according to published methods49. Anti-phosphohistone 3 antibodies (1:500, Millipore, USA) and anti-mouse Alexa fluor 488 stained for proliferating cells in 24 hpf whole-mount embryos. Cell death in 24 hpf and 48 hpf embryos were detected with TUNEL assay TMR red (Roche, USA). For cryosectioning, 4% PFA fixed embryos were embedded and oriented in 2% bactoagar (BDH, USA) and soaked in 30% sucrose (BD, USA) overnight. The agar blocks were trimmed and covered with Tissue-Tek O.C.T medium (Sakura, Japan) before being sectioned at 15 μm thickness using Microm HM 505 cryostat chamber (Carl Zeiss, Germany). The sections were collected with PolysineTM coated slides (Menzel GmbH and Co, Germany), and labelled for proliferating cells with anti-phosphohistone 3 antibodies and anti-mouse POD at a dilution of 1:500, before being stained with DAB (2,4-Diaminobutyric Acid) (Sigma-Aldrich, USA).

Microarray

To identify potential Yap1 downstream targets, total DNA-free RNA was extracted from wild type embryos, yap1 morphants (p53 MO not co-injected) and embryos injected with yap1 mRNA at 30 hpf using RNA purification kit (Qiagen, Germany). Using the extracted RNA, a first strand of cDNA was synthesized with SuperScriptIII kit (Stratagene, USA) and oligo dT primer provided. The synthesized cDNA was further amplified and labelled with Quick Amp Labelling Kit (Agilent Technologies, USA). Putative targets down-regulated in yap1 morphants were identified using methods in accordance to the Two-Colour Microarray-Based Gene Expression Analysis (Agilent Technologies, USA). Common down-regulated targets that occurred in both E1I1 and 5′UTR morphants that exhibited at least a two-fold decrease in expression when compared to expression of these genes in wild type embryos were selected for further analysis. The signaling pathways in the microarray data were analyzed using the DAVID bioinformatics database50.

Real Time Semi-quantitative RT-PCR

Total DNA-free RNA were extracted at 30 hpf with RNA purification kit (Qiagen, Germany). Gene-specific primers of actin, yap1 and prox1a were designed (1st BASE), sequence were as follows: actin forward, 5′-ATGATGCCCCTGGTGCTGTTTTC-3′; actin reverse, 5′-TCTCTGTTGGCTTTGGGATTCA- 3′; yap1 forward, 5′-GATAAAGCGGCCGGACACAGA-3′, yap1 reverse 5′-AGGTGGTTTTGTTCTTGTGAT-3′; prox1a forward, 5′-AGAACGCGGCAACTCAAACTACA -3′; prox1a reverse, 5′-CCATCATGCTCTGCTCCCGAATAA-3′. Observation of band-shift in yap1 RNA transcript of morphants was performed with One-Step RT-PCR (Qiagen, Germany) and gel electrophoresis. One-step RT-PCR with SYBR Green was performed according to manufacturer's manual (BioRad, USA) and ran in DNA Engine Opticon System (MJ Research, USA). Threshold cycle of each target gene in control and morphant was determined by using a housekeeping gene, actin, as a reference gene loading control for normalization. Fold change was calculated with delta-C(t) method and Microsoft Excel Student's two tailed t-test with respect to mismatch control. Primers that detect band-shift in yap1 RNA transcript from One-step RT-PCR gel electrophoresis analysis was: 277F, 5′-GATAAAGCGGCCGGACACAGA-3′: 1027R, 5′-AGGTGGTTTTGTTCTTGTGAT-3′.

Image acquisition and analysis

Observation and imaging of embryos were done using microscopes: Olympus AX70 (Olympus, Japan), Zen LSM700 and Zeiss Axioplan 2 (Carl Zeiss, Germany). Brightness and contrast, maximum projection of images and PrimI volume measurement were processed using ImageJ (NIH, USA) and Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, USA).

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed experiments: W.J.H., S.L.L., V.K. Performed the experiments: S.L.L., C.T., V.K. Analyzed the data: S.L.L., J.M., E.G., V.K. Wrote the paper: S.L.L., V.K.

Supplementary Material

Zebrafish yap1 plays a role in terminal differentiation and functionality of hair cells in posterior lateral line.

Acknowledgments

We thank personnel of the IMCB fish facility for maintenance of fish lines.

References

- Chan S. W. et al. The Hippo pathway in biological control and cancer development. J. Cell Physiol. 226, 928–39 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudol M. Newcomers to the WW Domain-Mediated Network of the Hippo Tumor Suppressor Pathway. Genes Cancer 1, 1115–8 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camargo F. D. et al. YAP1 increases organ size and expands undifferentiated progenitor cells. Curr. Biol. 17, 2054–2060 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X., Pfaff S. L. & Gage F. H. YAP regulates neural progenitor cell number via the TEA domain transcription factor. Genes Dev. 22, 3320–34 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudol M. Yes-associated protein (YAP65) is a proline-rich phosphoprotein that binds to the SH3 domain of the Yes proto-oncogene product. Oncogene 9, 2145–52. (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Wu S., Barrera J., Matthews K. & Pan D. The Hippo signaling pathway coordinately regulates cell proliferation and apoptosis by inactivating Yorkie, the Drosophila Homolog of YAP. Cell 122, 421–34 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudol M. et al. Characterization of the mammalian YAP (Yes-associated protein) gene and its role in defining a novel protein module, the WW domain. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 14733–41 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q. et al. yap is required for the development of brain, eyes, and neural crest in zebrafish. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 384, 114–9 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee S. T., Milgram S. L., Kramer K. L., Conlon F. L. & Moody S. A. Yes-associated protein 65 (YAP) expands neural progenitors and regulates Pax3 expression in the neural plate border zone. PLoS One 6, e20309 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J. et al. Elucidation of a universal size-control mechanism in Drosophila and mammals. Cell 130, 1120–33 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong W. & Guan K. L. The YAP and TAZ transcription co-activators: Key downstream effectors of the mammalian Hippo pathway. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 23, 785–93 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont S. et al. Role of YAP/TAZ in mechanotransduction. Nature 474, 179–83 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aragona M. et al. A mechanical checkpoint controls multicellular growth through YAP/TAZ regulation by actin-processing factors. Cell 154, 1047–59 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas P. & Gilmour D. Chemokine signaling mediates self-organizing tissue migration in the zebrafish lateral line. Dev. Cell 10(5), 673–80 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Schier H. & Hudspeth A. J. A two-step mechanism underlies the planar polarization of regenerating sensory hair cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 103, 18615–20 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghysen A. & Dambly-Chaudière C. The lateral line microcosmos. Genes Dev. 21, 2118–2130 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitnis A. B., Nogare D. D. & Matsuda M. Building the posterior lateral line system in zebrafish. Dev. Neurobiol. 72, 234–55 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas E. et al. The Hippo pathway polarizes the actin cytoskeleton during collective migration of Drosophila border cells. J Cell Biol. 201, 875–85 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aman A. & Piotrowski T. Wnt/beta-catenin and Fgf signaling control collective cell migration by restricting chemokine receptor expression. Dev. Cell 15, 749–61 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessarab D. A., Chong S. W. & Korzh V. Expression of zebrafish six1 during sensory organ development and myogenesis. Dev Dyn 230, 781–6 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nechiporuk A. & Raible D. W. FGF-dependent mechanosensory organ patterning in zebrafish. Science 320, 1774–7 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aman A. & Piotrowski T. Cell-cell signaling interactions coordinate multiple cell behaviors that drive morphogenesis of the lateral line. Cell. Adh. Migr. 5, 499–508 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma E. Y. & Raible D. W. Signaling pathways regulating zebrafish lateral line development. Curr. Biol. 12, R381–386 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go W., Bessarab D. & Korzh V. atp2b1a tagged in enhancer trap zebrafish transgenic line SqET4 controls a number of mechanosensory hair cells. Cell Calcium 48, 302–313 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. et al. Prox1a activity controls pancreas morphogenesis and participates in the production of “secondary transition” pancreatic endocrine cells. Dev. Biol. 286, 182–94 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui W., Tomarev S. I., Piatigorsky J., Chepelinsky A. B. & Duncan M. K. Mafs, Prox1a, and Pax6 can regulate chicken betaB1-crystallin gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 11088–95 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. W., Gao W., Teh H. L., Tan J. H. & Chan W. K. Prox1a is a novel coregulator of Ff1b and is involved in the embryonic development of the zebra fish interrenal primordium. Mol. Cell Biol. 23, 7243–55 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misra K., Gui H. & Matise M. P. Prox1 regulates a transitory state for interneuron neurogenesis in the spinal cord. Dev. Dyn. 237, 393–402 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow E. & Tomarev S. I. Restricted expression of the homeobox gene prox 1 in developing zebrafish. Mech. Dev. 76, 175–8 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pistocchi A. et al. The zebrafish prospero homolog prox1a is required for mechanosensory hair cell differentiation and functionality in the lateral line. BMC Dev. Biol. 9, 58 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan W., Martin D. & Gutkind J. S. The Galpha13-Rho signaling axis is required for SDF-1-induced migration through CXCR4. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 39542–9 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu F. X. et al. Regulation of the Hippo-YAP pathway by G-protein-coupled receptor signaling. Cell 150, 780–91 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Möhle R. & Drost A. C. G protein-coupled receptor crosstalk and signaling in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1266, 63–7 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karalay O. et al. Prospero-related homeobox 1 gene (Prox1a) is regulated by canonical Wnt signaling and has a stage-specific role in adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 108, 5807–12 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain S. et al. Differential requirement for beta-catenin in epithelial and fiber cells during lens development. Dev. Biol. 321, 420–33 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ober E. A., Verkade H., Field H. A. & Stainier D. Y. Mesodermal Wnt2b signalling positively regulates liver specification. Nature 442, 688–91 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmour D. T., Maischein H. M. & Nüsslein-Volhard C. Migration and function of a glial subtype in the vertebrate peripheral nervous system. Neuron 34, 577–88 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parinov S., Kondrichin I., Korzh V. & Emelyanov A. Tol2 transposon-mediated enhancer trap to identify developmentally regulated zebrafish genes in vivo. Dev. Dynam. 231, 449–459 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondrychyn I., Garcia-Lecea M., Emelyanov A., Parinov S. & Korzh V. Genome-wide analysis of Tol2 transposon reintegration in zebrafish BMC Genomics. 10, 418 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fong S. H., Emelyanov A., Teh C. & Korzh V. Wnt signalling mediated by Tbx2b regulates cell migration during formation of the neural plate. Development 132, 3587–3596 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlosser G. Making senses development of vertebrate cranial placodes. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 283, 129–234 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapède D., Gompel N., Dambly-Chaudière C. & Ghysen A. Cell migration in the postembryonic development of the fish lateral line. Development 129, 605–15 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaffney C. J. et al. Identification, basic characterization and evolutionary analysis of differentially spliced mRNA isoforms of human YAP1 gene. Gene 509(2), 215–22 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilman D. & Gat U. The evolutionary history of YAP and the hippo/YAP pathway. Mol Biol Evol. 28(8), 2403–17 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overholtzer M. et al. Transforming properties of YAP, a candidate oncogene on the chromosome 11q22 amplicon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 103, 12405–10 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandre D. & Ghysen A. Somatotopy of the lateral line projection in larval zebrafish. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 96, 7558–62 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blesa J. R. et al. NRF-1 is the major transcription factor regulating the expression of the human TOMM34 gene. Biochem. Cell Biol. 86, 46–56 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerfield M. (2000) The Zebrafish Book: a Guide for the Laboratory Use of Zebrafish. The University of Oregon Press.

- Korzh V., Sleptsova-Friedrich I., Liao J., He J. & Gong Z. Expression of zebrafish bHLH genes ngn1 and nrD define distinct stages of neural differentiation. Dev. Dynam. 213, 92–104 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D. W., Sherman B. T. & Lempicki R. A. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID Bioinformatics Resources. Nature Protoc. 4, 44–57 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Zebrafish yap1 plays a role in terminal differentiation and functionality of hair cells in posterior lateral line.