Abstract

The HIV gp41 protein catalyzes fusion between viral and target cell membranes. Although the ~20-residue N-terminal fusion peptide (FP) region is critical for fusion, the structure of this region is not well-characterized in large gp41 constructs that model the gp41 state at different times during fusion. This paper describes solid-state NMR (SSNMR) studies of FP structure in a membrane-associated construct (FP-Hairpin) which likely models the final fusion state thought to be thermostable trimers with six-helix bundle structure in the region C-terminal of the FP. The SSNMR data show that there are populations of FP-Hairpin with either α helical or β sheet FP conformation. For the β sheet population, measurements of intermolecular 13C-13C proximities in the FP are consistent with a significant fraction of intermolecular antiparallel β sheet FP structure with adjacent strand crossing near L7 and F8. There appears to be negligible in-register parallel structure. These findings support assembly of membrane-associated gp41 trimers through inter-leaving of N-terminal FPs from different trimers. Similar SSNMR data are obtained for FP-Hairpin and a construct containing the 70 N-terminal residues of gp41 (N70) which is a model for part of the putative pre-hairpin intermediate state of gp41. FP assembly may therefore occur at an early fusion stage. On a more fundamental level, similar SSNMR data are obtained for FP-Hairpin and a construct containing the 34 N-terminal gp41 residues (FP34) and support the hypothesis that the FP is an autonomous folding domain.

Keywords: HIV, gp41, structure, fusion peptide, NMR

INTRODUCTION

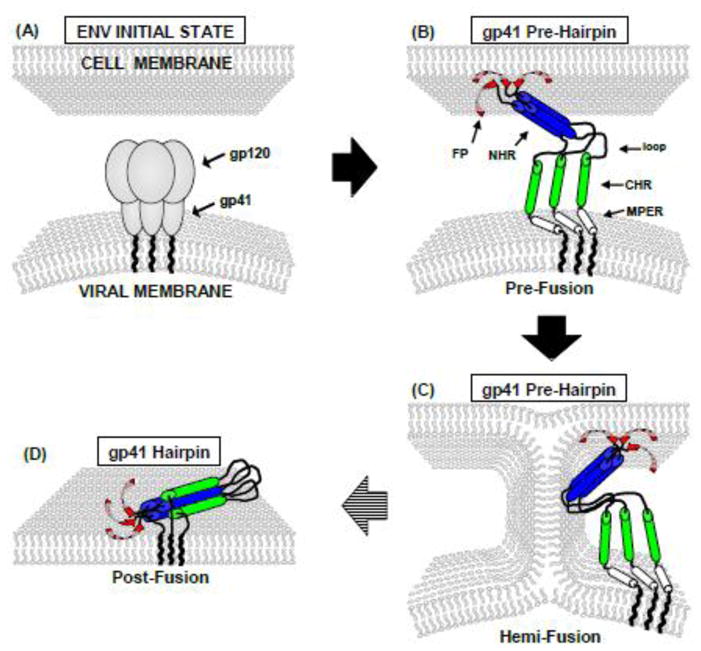

The initial step of infection by HIV involves fusion between viral and host cell membranes at or near physiologic pH.1 Membrane fusion is facilitated/catalyzed by the HIV gp120/gp41 protein complex where gp41 is a monotopic integral membrane protein and gp120 is non-covalently associated with the gp41 ectodomain, i.e. the N-terminal ~175-residues that are outside the virus (fig. 1). It is likely that gp41 is assembled as a trimer and each trimer has three associated gp120s (fig. 2).2 Binding of gp120 to target cell receptors triggers a change in the gp120/gp41 structural topology followed by putative binding of the ~20-residue N-terminal “fusion peptide” (FP) residues of gp41 to the target cell membrane and gp41 structural changes.3

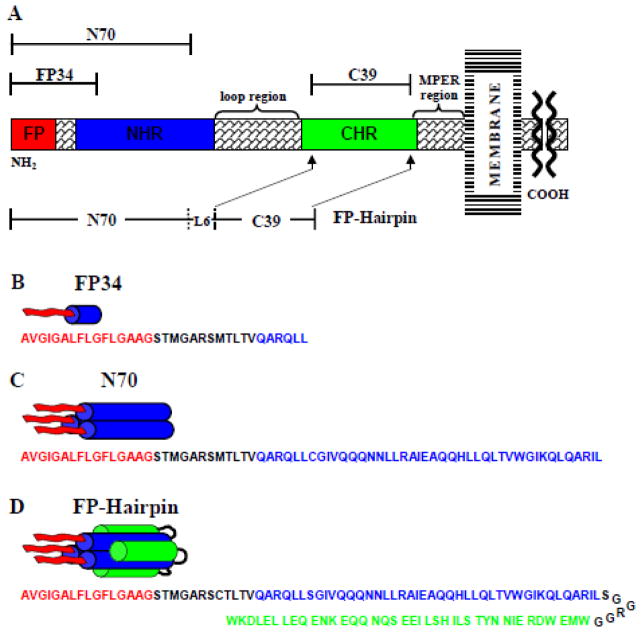

Fig. 1.

(A) Schematic of the HIV gp41 ectodomain. Primary functional regions are designated by colored boxes and additional functional regions are specified above in braces. Above and below in brackets are the gp41 fragments under study. (B–D) Structural models of FP34, N70, and FP-Hairpin (N70(L6)C39), with primary sequence given below each and color coded to match functional regions in (A). “NHR” and “CHR” respectively mean N-heptad and C-heptad repeats and are an alternate terminology for the N- and C-helices. MPER means “membrane-proximal external region”.

Fig. 2.

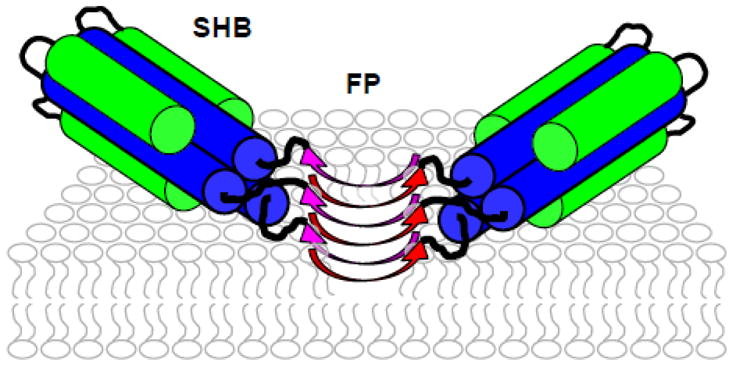

Qualitative working model of HIV gp41-mediated fusion with colors matched to Fig. 1. “NHR” and “CHR” respectively mean N-heptad and C-heptad repeats and are an alternate terminology for the N- and C-helices. MPER means “membrane-proximal external region”. (A) Prior to interaction with cell receptors, gp41 and gp120 form a non-covalent complex that is likely trimeric. (B–D) Following gp120/receptors interaction, gp41 mediates membrane fusion through protein-membrane interaction. There is substantial experimental evidence supporting multiple trimers at the fusion site but for clarity, only one trimer is shown. The model includes an early extended PHI (B–C) and final compact SHB (D) state of gp41. Studies of HIV-cell, cell-cell, and vesicle fusion support gp41 in the PHI state for most fusion steps. Membrane-inserted β structure is shown for the FP region and is based on (primarily SSNMR) data for the 23-residue HFP. Fig. 9 provides a more biophysically realistic model of antiparallel β sheet structure with two trimers.

gp41-mediated membrane fusion is often pictured as a time-series of structural states for the “soluble ectodomain” which is C-terminal of the FP. These states include an early “pre-hairpin intermediate” (PHI) and final “six-helix bundle” (SHB) in which the soluble ectodomain is either extended or compact, respectively (fig. 2). The PHI state has been postulated from peptide inhibitors of fusion as well as interpretations of electron density in cryoelectron tomography.1,4 The SHB state is supported by atomic-resolution structures of parts of the soluble ectodomain that show a hairpin motif for individual gp41 molecules, i.e. N-helix–180° turn–C-helix motif (fig. 1).1,5–7 In figs. 1 and 2, “NHR” and “CHR” respectively mean N-heptad and C-heptad repeats and are an alternate terminology for the N- and C-helices. MPER means “membrane-proximal external region”. In addition, gp41 molecules are assembled as trimers with three interior N-helices in parallel coiled-coil configuration and three exterior C-helices antiparallel to the N-helices. Antibody-binding studies of FP+N-helix constructs that model the N-PHI were interpreted to support a significant fraction of molecules with parallel trimeric coiled-coil N-helices (fig. 1C).8 In our view, most functional and electron microscopy data support a requirement of multiple gp41 trimers for fusion.9–11 There are little higher-resolution structural data about these assemblies of trimers and one contribution of the present work is insight into gp41 inter-trimer structure.

There are conflicting ideas about the roles of the putative early-stage PHI and final SHB gp41 states in fusion catalysis. One hypothesis is membrane fusion contemporaneous with the PHI→SHB structural change, although in our view, there are few supporting experimental data.12 The underlying thinking is that some of the free energy released during this change provides the work to move lipid molecules along the fusion reaction coordinate. Fig. 2 presents an alternate model in which most membrane fusion steps occur while gp41 is in the putative PHI state. These steps include inter-membrane lipid mixing (hemifusion) and initial fusion pore formation. The final SHB state stabilizes the fused membranes including the fusion pore and induces fusion arrest. This model is supported by experimental results including: (1) the nascent fusion pores formed in gp41-mediated cell-cell fusion are closed upon addition of a peptide which likely prevents the PHI → SHB structural change; (2) HIV infection and gp41-mediated cell-cell fusion are inhibited by soluble ectodomain constructs of gp41 with SHB structure; (3) gp41 ectodomain constructs that model the PHI induce rapid vesicle fusion at physiologic pH whereas those with SHB structure induce negligible fusion; and (4) vesicle fusion induced by shorter FP constructs (including a PHI model) is inhibited by SHB constructs.12–15

The functional significance of the FP has been demonstrated by reduction/elimination of HIV/cell fusion and HIV infection with some FP mutations.9 Similar functional effects of these mutations are detected in gp41-mediated cell/cell fusion.16 The functional importance of the FP has been further supported with observations of vesicle fusion induced by some FP-containing gp41 ectodomain constructs in the absence of gp120 and cellular receptors.17,18 The mutation-fusion activity relationships are similar to what is observed in HIV/cell and cell/cell fusion.19,20 For FP-containing gp41 constructs that model the PHI and SHB states, native gels/Western blots show higher molecular weight bands that may correspond to oligomers of trimers whereas there is often only a single trimer band in the absence of FP.8 Thus, one FP function may be oligomerization of trimers. Membrane insertion of short FP constructs may be similar to insertion of the gp41 FP in the target cell membrane during fusion.20,21

Higher-resolution structural data has been obtained for short FP constructs. For example, solid-state NMR (SSNMR) has been applied to “HFP” which contains the 23 N-terminal residues of gp41. HFP is bound to membranes that contain physiological fractions of anionic lipids and cholesterol.22 SSNMR data including chemical shifts and internuclear proximities are consistent with small oligomers with intermolecular antiparallel β sheet structure.23,24 A significant fraction of adjacent strands cross near L7 and F8. The β sheet HFP oligomer inserts into but does not traverse the membrane bilayer with deeper insertion of residues in the β sheet center (e.g. A6 and L9) and membrane surface location of residues near the β sheet termini (e.g. A1 and A14).21 In membranes lacking cholesterol, there are two populations with either α helical or β sheet structure.20,25,26 Other biophysical data are also consistent with these two populations.19,27–31

There are little FP structural data for larger gp41 constructs that model either the early PHI or final SHB gp41 states and it is therefore not known whether the detailed HFP structure is a good model for the PHI or SHB FP. This motivates the present study which provides extensive data for the FP-Hairpin construct that contains most of the N- and C-helix regions as well as a short non-native loop (fig. 1D). Earlier circular dichroism, calorimetric, and SSNMR data for FP-Hairpin are consistent with highly helical structure for the region C-terminal of the FP and therefore support SHB structure.32 The 13CO shift distribution of L7 in the FP is consistent with distinct populations of molecules with either a β sheet or α helical FP. The present study provides shift data for four additional FP residues. Data are also provided about the fractional populations of parallel and antiparallel β sheet FPs of FP-Hairpin with insight into the assembly of multiple gp41 trimers during HIV/host cell fusion. We think that this is the first information about β sheet FP of gp41 in its final SHB state.

This paper also provides comparative data for the FP34 and N70 constructs that are respectively the N-terminal 34 and 70 residues of gp41 (fig. 1B, C). N70 has the FP and much of the N-helix and is a model of the N-PHI. Earlier SSNMR work showed large populations of FP34 and N70 with β sheet FPs.32 There are large differences in the rates and extents of vesicle fusion induced by FP34, N70, and FP-Hairpin at physiologic pH: moderate, high, and negligible fusogenicities, respectively. The dramatic functional difference between the PHI model, N70, and the SHB model, FP-Hairpin, supports earlier work showing: (1) most HIV/cell fusion happens with gp41 in the PHI state; and (2) SHB gp41 is an inhibitor of HIV fusion and infection. A fraction of N70 likely forms parallel trimers and larger oligomers and the fusion rate of N70 is similar to that of a trimeric cross-linked HFP.17 FP trimers/oligomers may therefore have an important role in the rapid vesicle fusion induced by N70 and in the HIV/cell fusion catalyzed by PHI gp41. However, there are also trimers/oligomer FPs in FP-Hairpin, so the negligible fusion induced by this construct likely reflects a counteracting effect of the appended SHB such as charge repulsion from a negatively charged membrane.18 Although β and α FP populations are observed for many FP-containing constructs, in our view there is not yet a clear experimental correlation between fusogenicity and FP conformation. Overall, understanding HIV/cell fusion requires more structural data (such as those described in this paper) on large, membrane-associated gp41 constructs that model the PHI and SHB states.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Sample preparation

FP-Hairpin had a single labeled (lab) and directly-bonded 13CO/15N spin pair in the FP region, i.e. at I4/G5, L7/F8, F8/L9, F11/L12, or L12/G13 (fig. 1). For both N70 and FP34, the lab spin pair was L7/F8. “Membrane” samples are prepared by initially solubilizing protein in 10 or 20 mM formate buffer at pH 3 (“Buffer”) followed by dropwise addition to a vesicle suspension buffered at pH 7, with a final pH of 7. The typical vesicle composition was DTPC:DTPG:cholesterol (8:2:5 mole ratio) which reflects dominant choline headgroup, significant negatively charged lipid, and approximate lipid:cholesterol ratio found in viral and host cell plasma membranes.22 “Membrane+D-malt” samples are similarly prepared except that the initial protein solution is Buffer + decyl maltoside (D-malt) detergent which is non-ionic and non-denaturing. D-malt was added with the intent of reducing protein aggregation. FP-Hairpin binds vesicles at pH 7 but does not induce inter-vesicle lipid mixing (i.e. no vesicle fusion).18 The thermostable SHB structure and lack of vesicle fusion of FP-Hairpin at pH 7 are not affected by D-malt. The protein+vesicle suspension is centrifuged and the hydrated pellet is transferred to a SSNMR rotor. In the manuscript, spectra and corresponding data for samples without D-malt are shown in black and with D-malt are shown in red.

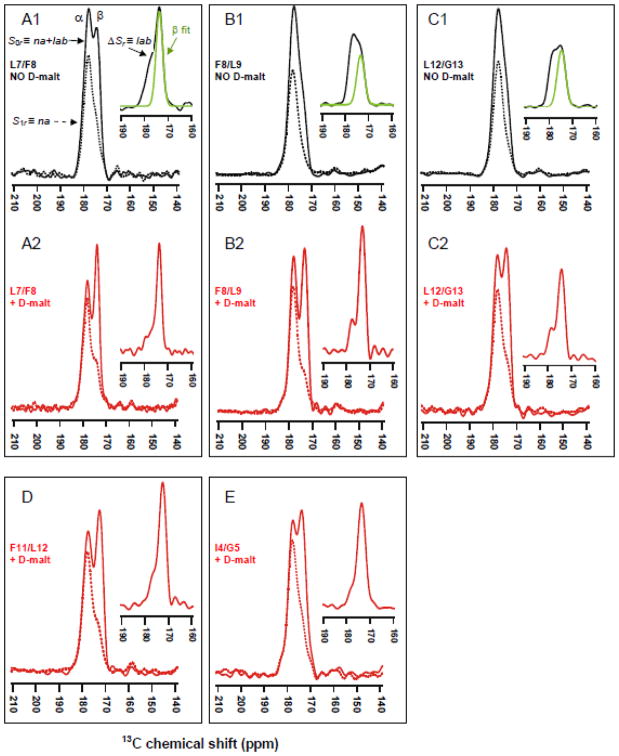

β and α FP populations of FP-Hairpin

As noted in the Introduction, an earlier SSNMR study showed approximately equal populations of FP-Hairpin molecules with either β or α structure at residue L7 in the FP region. One of the goals of the present study is delineation of these populations at other residues in the FP region. These populations provide a more global view of membrane-associated FP structure with C-terminal SHB, which likely models the final fusion state of gp41 (fig. 2).

Each FP-Hairpin molecule contains 1 lab and 144 unlabeled CO sites. Although there is only 0.011 13C natural abundance (na) at each unlabeled site, an unfiltered 13CO spectrum will have a total 0.61 fractional contribution from all of the na sites and corresponding 0.39 fractional contribution from the lab site. The unfiltered spectrum is therefore not useful for determination of the fractional β and α populations at the lab residue. This determination requires selective detection of the lab 13CO signal and was done using the rotational-echo double-resonance (REDOR) pulse sequence.33–36 The interpretation and analysis of the resulting REDOR spectra are illustrated with Fig. 3A1 from the membrane sample with L7/F8 (13CO/15N) labeling. The lower-left black and dashed traces are the “S0r” and “S1r” spectra, respectively, and the upper-right black trace is the ΔSr = S0r − S1r difference spectrum. The S0r, S1r, and ΔSr spectra respectively represent the total na + lab, na, and lab 13CO signals. Interpretation of the peaks in these spectra relies on the well-described correlation between local β or α structure and respective lower or higher backbone 13CO shift.25,37 The higher shift peak in the S0r spectrum is therefore considered to have a large contribution from na sites in the highly helical SHB domain while the lower shift peak is dominated by the lab signal from molecules with β conformation at the lab residue. The S1r spectrum reflects the na signal and the higher shift α peak is dominant. By contrast, the ΔSr spectrum reflects the lab signal and the lower shift β peak is dominant.

The determination of the fractional β and α populations at the lab residue is based on deconvolution of the ΔSr spectrum into lineshapes that are assigned to β and α structure based on peak shift. The fractional β and α populations are the fractional integrated intensities of their respective lineshapes. The green traces in panels A1, B1, and C1 are the deconvolved β lineshapes and complete deconvolutions for all spectra are provided in the SI. Each sum of lineshapes matches well to the experimental spectrum and the peak shifts, linewidths, and fractional integrated intensities from the deconvolutions are listed in Table I.

Table I.

Fitting of FP-Hairpin ΔSr spectra.a

| Sample/(13CO label) | β sheetb | α helixb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak shift (ppm) | Linewidthc (ppm) | Fractional intensity | Peak shift (ppm) | Linewidthc (ppm) | Fractional intensity | |

| Membrane/(L7) | 173.8 | 3.0 | 0.60 | 177.3 | 4.0 | 0.35 |

| 180.6 | 2.6 | 0.05 | ||||

| Membrane+D-malt/(L7) | 174.0 | 2.4 | 0.73 | 177.1 | 3.6 | 0.22 |

| 180.0 | 1.6 | 0.05 | ||||

| Membrane/(F8) | 173.4 | 3.9 | 0.43 | 177.0 | 4.1 | 0.57 |

| Membrane+D-malt/(F8) | 173.3 | 3.0 | 0.80 | 177.5 | 3.1 | 0.20 |

| Membrane/(L12) | 174.7 | 4.1 | 0.52 | 178.7 | 4.2 | 0.48 |

| Membrane+D-malt/(L12) | 174.2 | 3.3 | 0.75 | 178.5 | 3.5 | 0.25 |

| Membrane+D-malt/(F11) | 172.6 | 3.3 | 0.76 | 176.3 | 3.9 | 0.24 |

| Membrane+D-malt/(I4) | 173.7 | 4.0 | 0.88 | 178.2 | 3.5 | 0.12 |

Spectra are displayed in fig. 3 insets and are fitted to the sum of two or three Gaussian lineshapes. The black (red) colors match the colors of the inset spectra. Fits are shown in the SI.

Conformation is assigned by similarity between the peak 13CO shift and the peak shift of the database distribution of the amino acid in a specific conformation. Database peak shifts (standard deviations) in ppm include: Leu, β strand, 175.7 (1.5); Leu, helix; 178.5 (1.3); Phe, β strand, 174.3 (1.6); Phe, helix; 177.1 (1.4); Ile, β strand, 174.9 (1.4); Ile, helix, 177.7 (1.3). Each β sheet shift of FP-Hairpin is within 1 ppm of the corresponding β sheet HFP shift where HFP residue (shift) include L7 (174.2), F8 (173.8), L12 (174.4), F11 (173.3), and I4 (174.5).

Full-width at half-maximum.

Higher β population in membrane+D-malt samples

The effect of the absence vs presence of D-malt in the initial protein solublization buffer is examined with comparison of the ΔSr fittings of samples with the same labeled protein, e.g. panels A1 vs A2, B2 vs B2, and C1 vs C2. The peak shifts agree to within ±0.3 ppm while linewidths in D-malt samples are narrower by 0.4 to 0.9 ppm. For membrane samples, there are approximately equal populations of molecules with either β or α structure at the lab site, as highlighted by comparison of the green (β lineshape) and black (full ΔSr) traces in panels A1, B1, and C1 insets. Membrane+D-malt samples have a larger β:α population ratio (~3). The narrower linewidths and higher β population with D-malt are clearly observed in the S0r spectra. D-malt is expected to reduce aggregation of FP-Hairpin so the β and α FP populations may respectively correlate with smaller and larger FP-Hairpin oligomers/aggregates in membranes, although we currently have no data about these oligomer sizes.

The β peak shifts of either a membrane or membrane+D-malt sample agrees to within 0.8 ppm with the corresponding shift of the membrane-associated HFP (which lacks the SHB).23 A large body of SSNMR data supports β sheet structure for HFP in membranes with cholesterol and this structure may be a reasonable model for the β sheet FP of membrane-associated FP-Hairpin.

The β and α FP populations observed for FP-Hairpin have also been observed for HFP and larger gp41 constructs (including a 154-residue ectodomain construct) with a variety of membrane compositions.38 One of these compositions specifically reflected the typical lipid headgroup and cholesterol content of membranes of host cells of the virus.39 The populations appear to reflect comparable free energies of the two structures and these populations have also been observed for fusion peptides from other viruses.40–43 It is possible, although we think unlikely, that the free energy difference between the β and α states is dramatically changed by inclusion of the transmembrane domain of gp41.30

Predominant antiparallel FP of membrane-associated FP-Hairpin

As noted in the Introduction, β sheet FP structure has been observed for the 23-residue HFP bound to membranes with cholesterol content comparable to that of host cell and viral membranes. There are also significant populations of molecules with β sheet FP for N70 and FP-Hairpin which are models of putative intermediate and final states of gp41, respectively. There is often rapid fusion of cholesterol-rich vesicles by FP constructs so the β sheet FP is likely fusogenic and it is worthwhile to make high-resolution measurements for this β structure in membranes. For small constructs such as HFP, earlier SSNMR studies were consistent with small oligomers of HFP with antiparallel β structure and ~0.4 fraction of adjacent molecules crossing near L7 and F8.24 There was no population of parallel β structure for HFP. However, it seems possible that parallel β FP structure could be promoted in FP-Hairpin as an extension of the parallel arrangement of the NHR regions (fig. 1D). This motivated the SSNMR experiments of the present study to detect populations of membrane-associated FP-Hairpin molecules with either parallel or antiparallel FPs.

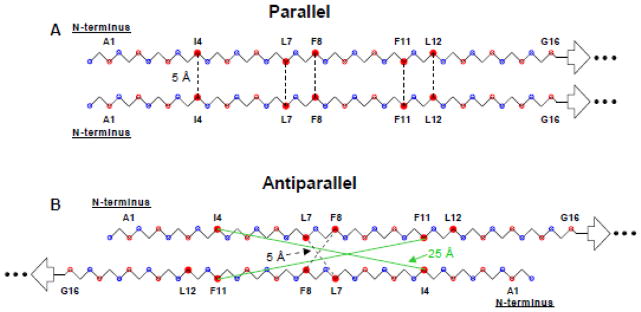

The samples for these experiments were the same as those described above and had a single lab 13CO nucleus in the FP region. SSNMR was applied to probe proximities between the lab 13CO nuclei on adjacent FP strands in the intermolecular β sheet. These proximities were then compared to those predicted for the parallel and antiparallel models displayed in Fig. 4. For the parallel model in fig. 4A, the intermolecular distance (≡ rll) between lab 13CO nuclei is ~5 Å and also independent of the identity of the lab residue, i.e. ~5 Å for the I4, L7, F8, F11, and L12 samples. For the antiparallel model in fig. 4B, the rll is strongly dependent on the identity of the lab residue, i.e. ~5 Å for the L7 and F8 samples and >20 Å for the I4, F11, and L12 samples. The dependence of the SSNMR-derived rll on lab site is used to assess the fractions of parallel and antiparallel strand arrangements.

Fig. 4.

Backbone models of two strands of the apolar (residues 1→16) FP region with either (A) in-register parallel 1→16/1→16 or (B) antiparallel 1→15/15→1 β sheet structure. Open blue and red circles are N and CO nuclei, respectively, and closed red circles are the 13CO labels used in this study. Some residues are identified. The following distances are used: (1) 3.35 Å between CO nuclei of adjacent residues in a single strand; (2) 5.0 Å between CO nuclei at the same residue position on adjacent strands in the parallel structure; and (3) 4.1 Å between C and N in a CO…HN hydrogen bond. For either model, the length of each dashed line represents 5 Å. For the antiparallel model, the intercarbonyl intermolecular distances for F11–F11 and I4–I4 are 23 Å and 25 Å, respectively, and are indicated by green lines. The L12 – L12 distance is 30 Å.

The rll of a sample was probed using the finite-pulse constant-time double-quantum build-up (fpCTDQBU) SSNMR technique.25,44–47 The 13CO-13C dipole-dipole coupling scales as r−3 and the fpCTDQBU method detects such couplings between proximal nuclei, i.e. those with 13CO-13C distance ≤ 10 Å. Some of the fpCTDQBU 13CO spectra and analysis are displayed in Figs. 5 and 6 with spectra denoted by S0f or S1f and respectively displayed with solid or dashed lines. The notation was consistent with the REDOR notation and the “f “ subscript refers to fpCTDQBU. Similar to the REDOR S0r spectra of Fig. 3, each fpCTDQBU 13CO S0f spectrum has a lower shift β peak dominated by the lab FP signal and a higher shift α peak dominated by the na SHB signal. The respective assignments of the β and α peaks to dominant lab FP and na SHB contributions are supported by good agreement between the β peak shifts of the S0f and ΔSr spectra, typically different by ≤ 0.3 ppm, and small sample-to-sample variation of the α peak shift, typically ≤ 0.5 ppm (Table II). Additional support for the assignments were much larger attenuations of the β signals relative to the α signals in the REDOR S1r spectra of fig. 3. We also use S0fβ and S0fα to respectively denote the β and α peak intensities of the S0f spectrum and S1fβ and S1fα to denote the corresponding intensities in the S1f spectrum.

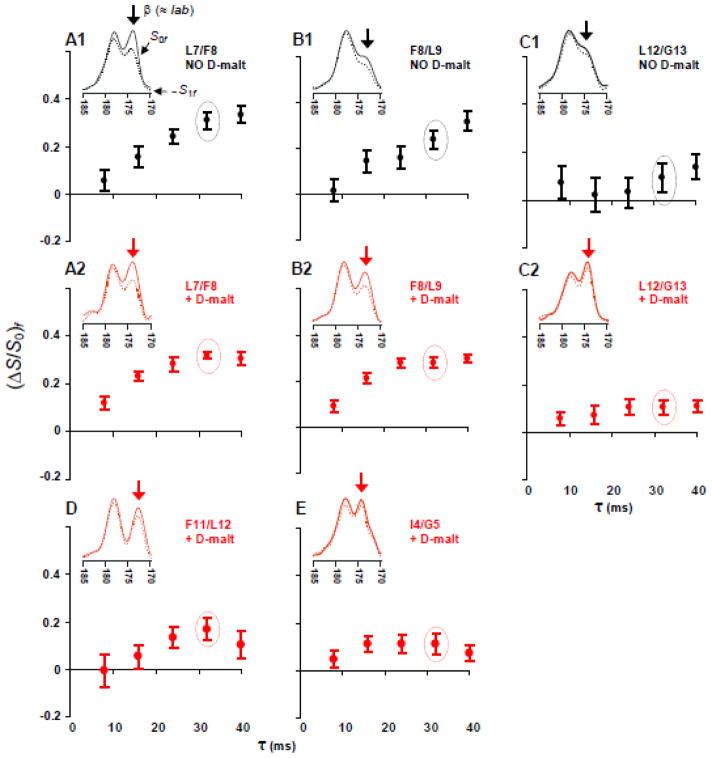

Fig. 5.

fpCTDQBU (ΔS/S0)fβ vs dephasing time τ for samples containing FP-Hairpin 13CO labeled at (A) L7, (B) F8, (C) L12, (D) F11, and (E) I4. Panels A1, B1, and C1 (black circles) are membrane samples and panels A2, B2, C2, D, and E (red circles) are membrane+D-malt samples. (A–E) Inset are experimental S0f (solid line) and S1f (dotted line) 13CO spectra for τ = 32 ms. Relative to S0f, attenuation of the S1f signal is due to 13CO-13C couplings. The (ΔS/S0)fβ are calculated using the 13CO spectral intensities integrated in a 1.0 ppm window centered at the β peak shift (denoted by an arrow). Spectral processing was typically done without line broadening and with polynomial baseline correction (see SI). Each S0f and S1f spectrum represents the sum of (A1) 15000, (A2) 12000, (B1) 12000, (B2) 11000, (C1) 14000, (C2) 12000, (D) 16000, and (E) 14000 scans.

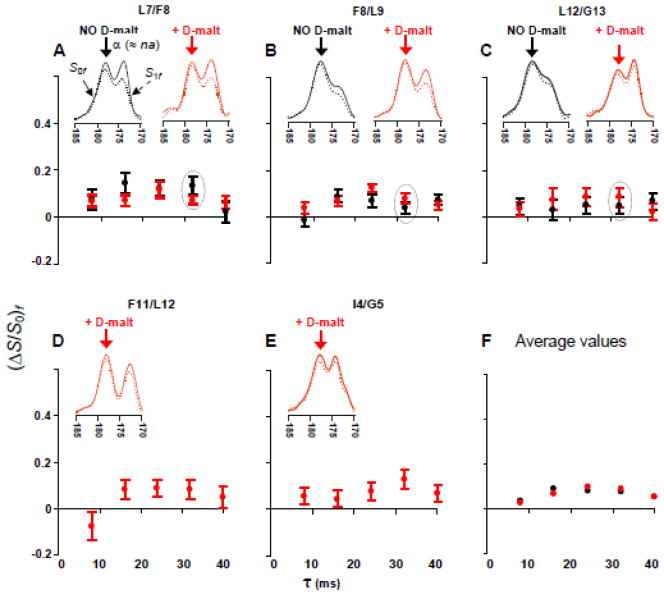

Fig. 6.

fpCTDQBU (ΔS/ S0)fα vs dephasing time for samples containing FP-Hairpin 13CO labeled at (A) L7, (B) F8, (C) L12, (D) F11, and (E) I4. Black circles are for membrane samples and red circles are for membranes+D-malt samples. Data are overlaid in panels A–C to compare samples with the same label prepared without or with D-malt. (F) The average (ΔS/S0)fα of membrane samples (black dots) or membranes+D-malt samples (red dots). (A–E) The insets are experimental S0f (solid line) and S1f (dotted line) 13CO spectra for τ = 32 ms. The (ΔS/S0)fα are calculated using the 13CO spectral intensities integrated in a 1.0 ppm window centered at the α peak shift (denoted by an arrow).

Fig. 3.

13CO REDOR spectra of samples containing FP-Hairpin with a single directly-bonded 13CO/15N spin pair at (A) L7/F8, (B) F8/L9, (C) L12/G13, (D) F11/L12, and (E) I4/G5. Samples A1, B1, and C1 (black spectra) were prepared with initial protein solubilization in Buffer, whereas samples A2, B2, C2, D, and E (red spectra) were prepared with solubilization in Buffer + D-malt. The solid and dotted lines are respectively the total na + lab (S0r) and the na (S1r) spectra. Inset in each figure is the lab spectrum (ΔSr) with deconvolved β sheet peak in green. Spectral processing included Gaussian line broadening of 150 and 100 Hz respectively for A1 and C2 as well as polynomial baseline correction for all spectra. Each S0r and S1r spectrum is the sum of (A1) 76128, (A2) 9328, (B1) 8928, (B2) 36597, (C1) 19856, (C2) 68308, (D) 20000, and (E) 51904 scans.

Table II.

S0r and S0f 13CO peak shifts (ppm) of FP-Hairpina

| Sample/(13CO label) | S0r | S0fb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β sheet | α helix | β sheet | α helix | |

| Membrane/(L7) | 174.1 | 177.8 | 174.1 | 178.2 |

| Membrane+D-malt/(L7) | 174.0 | 178.2 | 174.1 | 178.5 |

| Membrane/(F8) | 173.4 | 177.7 | 173.5 | 177.8 |

| Membrane+D-malt/(F8) | 174.4 | 178.0 | 173.7 | 178.3 |

| Membrane/(L12) | 174.3 | 178.2 | 174.4 | 178.4 |

| Membrane+D-malt/(L12) | 174.5 | 178.3 | 174.4 | 178.2 |

| Membrane+D-malt/(F11) | 172.9 | 177.6 | 172.9 | 178.2 |

| Membrane+D-malt/(I4) | 174.3 | 177.9 | 174.3 | 177.9 |

Most spectra have well-resolved β and α peaks and the peak shifts were measured by visual inspection. For the more poorly-resolved membrane/(F8) and membrane/(L12) samples, the peak shifts were measured by deconvolution.

Each S0f shift is the average for all τ values. For any particular sample, the standard deviation of the shift distribution is 0.1–0.2 ppm.

For the β fpCTDQBU signals dominated by lab 13CO nuclei, larger lab 13CO-lab 13CO couplings and corresponding shorter rll are indicated by higher attenuation of S1fβ relative to S0fβ. For example, the panel A1 and A2 spectra of Fig. 5 show significant β signal attenuation for the L7 sample that is consistent with adjacent strands with proximal L7 residues. Attenuation is quantitated using the intensity ratio (S0fβ − S1fβ)/S0fβ = (ΔS/S0)fβ. The fpCTDQBU spectra were obtained for five different values of the dephasing time (τ) and significant buildup of (ΔS/S0)fβ with τ was an indicator of proximal lab 13CO nuclei on adjacent strands. Fig. 5 displays plots of (ΔS/S0)fβ vs τ for the different samples with inset spectra corresponding to τ = 32 ms. For a particular lab FP-Hairpin, the (ΔS/S0)fβ build-up is typically comparable for the membrane and membrane+D-malt samples. Uncertainties are usually smaller for the membrane+D-malt samples because of the higher fractional population with β FP and because of narrower β linewidths.

The (ΔS/S0)fβ data are first interpreted in terms of the dominant contribution of the lab 13CO nuclei to the β signal and intermolecular lab 13CO-lab 13CO couplings due to rll. This basic interpretation is not changed by more detailed analysis which also considers the minor contribution of na 13CO nuclei to the β signal as well as couplings to na 13C nuclei. This detailed analysis is presented in a subsequent section of the paper.

The (ΔS/S0)fβ data can be separated into two categories: (1) L7 and F8 samples for which (ΔS/S0)fβ reaches 0.3 – 0.4 for τ ≥ 32 ms; and (2) I4, F11, and L12 samples for which (ΔS/S0)fβ ≤ 0.1 for τ ≥ 32 ms. The I4, F11, and L12 data correlate to rll > 10 Å and are therefore inconsistent with a significant population of parallel strand arrangement for which rll ≈ 5 Å for all residues (fig. 4A). The I4, F11, and L12 data are consistent with a significant population of antiparallel arrangement for which rll > 10 Å for these residues (fig. 4B). For this antiparallel arrangement with adjacent strand crossing near L7 and F8, the rll ≈ 5 Å for the L7 and F8 samples. For 100% population of this antiparallel arrangement and rll ≈ 5 Å, the (ΔS/S0)fantipar will build up to ~0.8 for τ ≥ 32 ms.25,46 However, for the L7 and F8 samples, (ΔS/S0)fβ ≈ 0.35 which suggests that only ~0.4 fraction of the FP-Hairpin molecules have these particular antiparallel registries. This result is consistent with the experimentally-derived ~0.4 fraction of these registries in membrane-associated HFP. It is likely that the remaining ~0.6 fraction for FP-Hairpin and HFP are in antiparallel registries with adjacent strand crossing at residues other than L7 and F8.

In summary, observation of a strong dependence of (ΔS/S0)fβ on lab site supports a significant fraction of antiparallel (fig. 4B) but not parallel (fig. 4A) structure for FP-Hairpin. The antiparallel structure of membrane-associated FP-Hairpin appears similar to that of membrane-associated HFP and supports the hypothesis of the FP as an autonomous β sheet folding unit in membranes.

Effects of na 13C nuclei

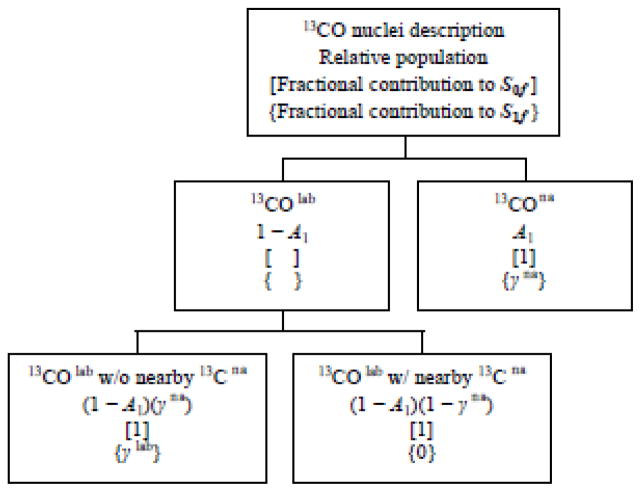

The analysis of the previous section is based on the reasonable approximations that the β 13CO signal is dominated by lab nuclei and that the (ΔS/S0)fβ buildups are dominated by lab 13CO-lab 13CO couplings. A more accurate analysis requires calculation of the effects of na 13C nuclei including: (1) the contribution of these nuclei to the β 13CO signal; and (2) 13CO-na 13C couplings.

Effect (1) is calculated based on S0fna and S0flab contributions to a total normalized S0fβ intensity, i.e. S0fβ = S0fna + S0flab = 1. The S0fna and S0flab values are calculated using S0fna = (S1/S0)rβ ≡ A and S0flab = 1 − A where S0rβ and S1rβ are the experimental intensities in the β region of the REDOR S0r and S1r spectra. The A value for each sample is presented in the SI. This approach to calculation of S0fna and S0flab is based on the reasonable approximations (S1/S0)rna = 1 and (S1/S0)rlab = 0 for samples with directly-bonded labeled 13CO/15N spin pairs.34,35 The same 1.0 ppm shift interval is used to calculate the S0rβ, S1rβ, S0fβ and S1fβ intensities.

The contribution of 13CO-na 13C couplings to the (ΔS/S0)fβ data (effect 2 above) is assessed using the (ΔS/S0)fα build-ups of the 13CO α signals (fig. 6). These (ΔS/S0)fα build-ups are dominated by na couplings as evidenced by: (1) (ΔS/S0)fα ≤ 0.1; and (2) (ΔS/S0)fα that are approximately independent of both the identity of the lab residue and the relative contributions of the na and lab 13CO nuclei to the α signal (fig. 3).

For each τ, the average (ΔS/S0)fα of the membrane+D-malt samples serve as consensus values of (ΔS/S0)f due to 13CO-na 13C couplings (red circles in fig. 6F). There are similar average (ΔS/S0)fα (to within 0.01) for the membrane samples (black circles in fig. 6F) and the (ΔS/S0)fα of each sample typically agrees within error with these averages. Because there are smaller uncertainties in the (ΔS/S0)fα of the membrane+D-malt samples, the average (ΔS/S0)fα (τ) ≡ 1 − γna(τ) of these samples are used to describe (ΔS/S0)f due to 13CO-na 13C couplings. Table III lists these 1 − γna(τ) values along with the corollary γna(τ) ≡ (S1/S0)fα(τ). In the remainder of the paper, the notation is typically simplified by not explicitly writing “(τ)”. A model for 1 − γna is described in the SI and yields calculated values in the 0.03–0.08 range that are consistent with the experimental values in Table III.

Table III.

| τ (ms) | γna | 1 − γna |

|---|---|---|

| 8 | 0.96 | 0.04 |

| 16 | 0.93 | 0.07 |

| 24 | 0.91 | 0.09 |

| 32 | 0.92 | 0.08 |

| 40 | 0.94 | 0.06 |

γna ≡ (S1/S0)f ratio from attenuation due to couplings to nearby na 13C nuclei. This ratio is the average of the experimental (S1/S0)fα ratios of the membrane + D-malt samples.

1 − γna ≡ (ΔS/S0)f ratio from attenuation due to couplings to nearby na 13C nuclei.

The S0fβ = S0fna + S0flab and the S1fβ = S1fna + S1f,lab. The attenuation of the S1fna β 13CO signal relative to the S0fna β 13CO signal depends on na 13CO-na 13C couplings whereas attenuation of the S1f,lab β 13CO signal relative to S0flab β 13CO signal depends on lab 13CO-na 13C couplings as well as lab 13CO-lab 13CO couplings. These lab 13CO-lab 13CO couplings are described by the parameter γlab = γlab(τ), i.e. the (S1/S0)f ratio for lab 13CO nuclei coupled to other lab 13CO nuclei in the β sheet. The variation of γlab (or equivalently 1 − γlab ≡ (ΔS/S0)flab) with lab residue provides detailed information about the populations of parallel and antiparallel β strand arrangements (fig. 4).

The γlab for each sample are calculated using a model outlined in Fig. 7. Aspects of the model include: (1) quantitative separation of the S0fβ signal into S0fna and S0flab fractions using (S1/S0)rβ ≡ A and 1 − A as described previously; (2) further separation of S0flab into fractions for which the lab 13CO nuclei are respectively close and far from na 13C nuclei; and (3) calculation of γlab using (1) and (2) as well as the experimentally-determined γna and (ΔS/S0)fβ. For the same labeling, there are similar (ΔS/S0)fβ build-ups for membrane and membrane+D-malt samples and the γlab values are calculated for the latter data which have larger and narrower signals.

Fig. 7.

Flow chart for the calculation of γlab which reflects intermolecular lab 13CO–lab 13CO dipolar couplings and distances.

This model results in an equation for the S0fβ signal:

| (1) |

The left-most A term is the signal of na 13CO nuclei and the [(1 − A) × (1 − γna)] and [(1 − A) × γna] terms are respectively the signals of lab 13CO nuclei close to and far from na 13C nuclei. The γ = (S1/S0)f, for each of these terms are respectively γna, 0, and γlab. The S1fβ signal:

| (2) |

The S1fβ and γlab depend on τ and labeled 13CO site. The quantity 1 − γlab is the (ΔS/S0)f for lab β sheet 13CO nuclei close to other lab 13CO nuclei and not close to na 13C nuclei. As noted above, 1 − γlab is diagnostic of the FP antiparallel β sheet strand registry distribution. Eqs. 1 and 2 are algebraically combined:

| (3) |

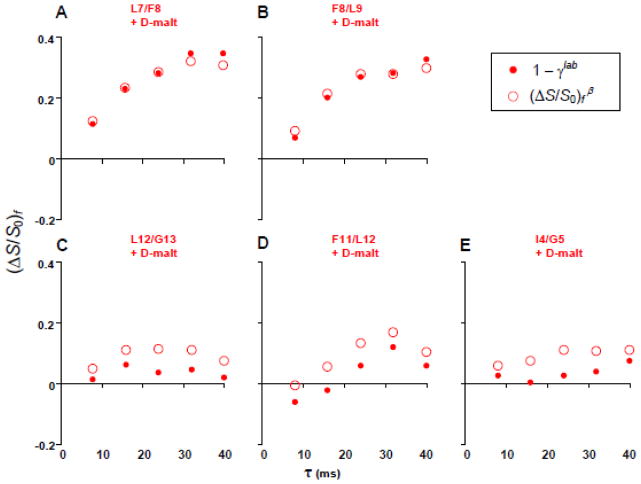

Fig. 8 displays the (ΔS/S0)fβ (open circles) and the 1 − γlab (closed circles) vs τ for the differently labeled membrane+D-malt samples. The 1 − γlab of the (A) L7 and (B) F8 samples reach ~0.35 for τ ≥ 32 ms and there are only small differences with the experimental (ΔS/S0)fβ, i.e. consideration of na 13C effects has little impact on the analysis. The 1 − γlab of the (C) L12, (D) F11, and (E) I4 samples are close to 0 and support negligible in-register parallel β sheet FP structure in FP-Hairpin. Consideration of na 13C effects for these samples results in reduced 1 − γlab relative to (ΔS/S0)f β. The 1 − γlab ≈ 0.35 values at τ ≥ 32 ms for the L7 and F8 samples support a significant antiparallel β sheet population (~0.4 fraction) with adjacent strand crossing near L7 and F8. This antiparallel β sheet structure is similar to that reported for membrane-associated HFP that contains the 23 N-terminal residues of gp41. These findings suggest that membrane-associated antiparallel β sheet FP oligomers are a stable structure either with or without the rest of the ectodomain. To our knowledge, this is the first higher-resolution study of the tertiary structure of the FP region of any larger gp41 ectodomain construct.

Fig. 8.

(ΔS/S0)fβ (open circles) and 1 − γlab (solid circles) vs dephasing time for membrane+D-malt samples with FP-Hairpin 13CO labeled at (A) L7, (B) F8, (C) L12, (D) F11, and (E) I4.

FP-Hairpin is a model for the final SHB gp41 state during HIV/host-cell membrane fusion. The SHB is a molecular trimer with the three FPs extending in parallel from the SHB. Our detection of FPs with oligomeric antiparallel β sheet structure in FP-Hairpin indicates interleaving of FP strands between two or more trimers (fig. 9). The membrane location of the FP in fig. 9 is based on earlier SSNMR data for HFP.21 The SHB is shown away from the membrane because both the SHB and the membrane are negatively charged at pH 7 and there may be considerable motion of the SHB.18,30

Fig. 9.

Schematic of membrane-associated FP-Hairpin at pH 7. There is a SHB and antiparallel β sheet FP structure so FP-Hairpin minimally oligomerizes as a dimer of trimers. The FP membrane location is chosen to be the same as the 23-residue HFP which lacks the SHB. The FP region binds negatively-charged membranes at pH 7 whereas the negatively charged SHB region may not bind these membranes.

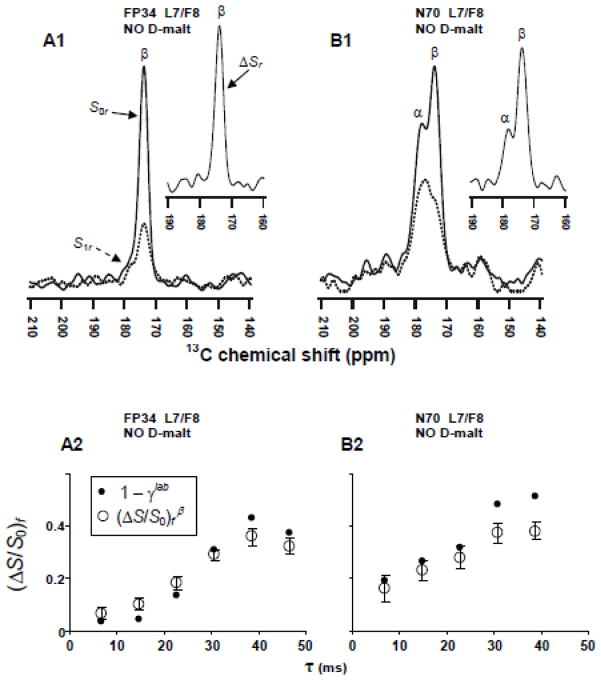

REDOR and fpCTDQBU spectra and analysis of FP34 and N70 in membranes

FP34 is the 34 N-terminal residues of gp41 and is a FP model while N70 is the 70 N-terminal residues and is a N-PHI model (fig. 2). Both constructs bind anionic membranes and induce vesicle fusion at physiologic pH.15,32 N70 is significantly more fusogenic than FP34 which may be due to formation of oligomers of N70 with parallel helical coiled-coils in the N-helix region and consequent clusters of FPs like in the model PHI structure. Fig. 10 displays REDOR spectra and fpCTDQBU (ΔS/S0)fβ build-ups of L7-13CO/F8-15N labeled FP34 and N70 in membranes. The 13CO ΔSr spectrum of the FP34 sample (fig. 10A1 inset) has a peak shift of 174 ppm that is consistent with predominant β conformation at L7. The 13CO ΔSr spectrum of the N70 sample (fig. 10B1 inset) has two peaks with shifts of 174 and 178 ppm that are respectively assigned to populations of N70 molecules with β and α conformation at L7. Figs. 10A2, B2 display plots of (ΔS/S0)fβ (open circles) and 1 − γlab (filled circles) for the two samples. Determination of 1 − γlab is done as described for FP-Hairpin. The analysis uses the γna from Table III with γna = 0.94 for τ ≥ 38 ms. The fpCTDQBU spectra are shown in the SI. The (ΔS/S0)fβ buildups of the L7-labeled FP34, N70, and FP-Hairpin samples are all comparable with values of ~0.35 for τ ≥ 32 ms. The 1 − γlab are also comparable and are consistent with ~0.4 fraction of adjacent strands crossing near L7 in the β sheet as has also been observed for HFP. Earlier HFP data as well as FP-Hairpin data from the present paper are consistent with antiparallel rather than parallel arrangement of adjacent FP strands in the β sheet.

Fig. 10.

SSNMR spectra of membrane samples containing (A1, A2) FP34 and (B1, B2) N70 with a L7 13CO/F8 15N spin pair. Panels A1, B1 display REDOR total S0r, na S1r, and lab ΔSr spectra as solid, dotted, and inset lines, respectively. Each S0r and S1r spectrum is the sum of (A1) 29136 and (B1) 76832 scans. Spectra are processed with 200 Hz Gaussian line broadening and baseline correction. Panels A2, B2 display fpCTDQBU (ΔS/S0)fβ (open circles) and 1 − γlab (solid circles) vs dephasing time. Each S0f and S1f spectrum is the sum of (A2) 20000 and (B2) 16000 scans.

We note that different earlier infrared studies of FP34 and N70 in membranes had been interpreted to support in-register parallel β sheet structure of the FP.48 This interpretation is based on ascribing spectral changes to inter- rather than intra-molecular electric dipole-electric dipole couplings. However, the peptides contained 13CO labels at sequential residues and the large intra-molecular couplings could not be distinguished from inter-molecular couplings.

In our view, the site-specific 13CO labeling of the present study was critical to provide unambiguous information about the FP regions of these larger membrane-associated gp41 constructs. Relative to uniform 13C labeling, there is spectral simplification with the specific labeling so that the peaks can be unambiguously assigned.49 This simplification is important because of the ~3 ppm 13CO linewidths (fig. 3) as well as the structural heterogeneity in the FP region including a mixture of β and α populations and a distribution of antiparallel strand registries.

CONCLUSIONS

SSNMR is applied to probe FP conformation and intermolecular FP β sheet structure of N70 and FP-Hairpin gp41 constructs that respectively model the putative early PHI and final SHB gp41 states during fusion. The shorter FP-only FP34 construct is also studied. The samples are prepared with membranes. FP-Hairpin is fusion-inactive at physiologic pH whereas N70 and FP34 are highly and moderately active, respectively. There are typically positive correlations between membrane cholesterol content and (1) β population and (2) rate and extent of vesicle fusion.17,29,32 The β and α structures have also been observed for the membrane-associated structures of fusion peptides of other viral fusion proteins.28,34,41–43 Our main findings and interpretations are summarized.

FP-Hairpin contains N- and C-helices that are C-terminal of the FP and are likely part of a SHB structure. There are two populations of FP-Hairpin with either β sheet or α helical FP structure.

Relative to initial solubilization of FP-Hairpin in Buffer, solubilization in Buffer+D-malt results in a sample with increased population with β FP. D-malt is expected to reduce aggregation of FP-Hairpin so the β and α FP populations may respectively correlate with smaller and larger FP-Hairpin oligomers/aggregates in membranes.

The FP-Hairpin 13CO α peaks are dominated by na signals of the N- and C-helices. The fpCTDQBU intensity ratios (S1/S0)fα = γna = γna(τ) are consistent with the dominance of couplings to na 13C nuclei. The samples have a directly-bonded 13CO/15N spin pair and the REDOR intensity ratio in the β region, A = (S1/S0)rβ, and 1 − A are respectively the fractional na and lab contributions to S0fβ. The A, γna, and (S1/S0)fβ values are used to calculate γlab = γlab(τ), the (S1/S0)fβ ratio of lab FP β 13CO nuclei coupled to other lab FP β 13CO nuclei. The variation of γlab values with lab site supports negligible FP population with in-register parallel β sheet structure and a significant population (>1/3 fraction) with antiparallel structure and adjacent strand crossing near L7 and F8 in the most apolar part of the FP. The remaining population is likely in antiparallel registries with adjacent strand crossing at residues other than L7 and F8. There may be interleaving of FP strands between two FP-Hairpin trimers (fig. 9).

The antiparallel β sheet FP structural model for FP-Hairpin in membranes is similar to the FP structure of membrane-associated HFP which only contains the 23 N-terminal residues of the gp41 protein. The FP sequence in membranes may therefore be an autonomous antiparallel β sheet folding unit.

The L7 13CO labeled samples containing either FP-Hairpin, N70, or FP34 all have comparable (ΔS/S0)fβ build-ups that indicate a significant population with strands crossing near L7. Like FP-Hairpin which models the final SHB gp41 state, FP34 and N70 (which models the intermediate PHI state) likely have antiparallel rather than parallel β sheet structure.

N70 induces rapid vesicle fusion at pH 7 whereas FP-Hairpin is fusion-inactive. This functional difference might be explained by: (1) deeper FP membrane insertion of N70 with consequent greater membrane perturbation; and/or (2) a somewhat different distribution of antiparallel FP registries for N70 that is correlated with higher hydrophobicity of the β-sheet; and/or (3) differential membrane perturbation by the N-helix of N70 vs the SHB of FP-Hairpin. Earlier studies on different HFP constructs showed that there is a strong positive correlation between depth of FP membrane insertion and vesicle fusion rate.21

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Boc and Fmoc amino acids, Boc-MBHA resin, and Fmoc-rink amide MBHA resin were purchased from Novabiochem (San Diego, CA). S-Trityl-β-mercaptopropionic acid was purchased from Peptides International (Louisville, KY). Di-tert-butyl-dicarbonate, Tris(2-Carboxyethyl) phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP), 4-mercaptophenylacetic acid, 2-mercaptoethanesulfonic acid sodium salt, and N-(2-Hydroxyethyl) piperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), were purchased from Sigma. 1,2-di-O-tetradecyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DTPC), 1,2-di-O-tetradecyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-rac-(1-glycerol) sodium salt (DTPG), and cholesterol were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). Labeled amino acids were purchased from Cambridge Isotopes Labs (Andover, MA) and were Boc-protected using literature methods.50 The Micro Bicinchoninic Acid (BCA) protein assay was obtained from Pierce (Rockford, IL). “Buffer” refers to 10 or 20 mM formate buffer, 200 μM TCEP, pH 3.

Protein preparation

The sequences (fig. 1) are from the HXB2 laboratory strain of the HIV-1 Envelope protein with names and residue numbering: (a) FP34(linker), 512-545-(thioester); (b) FP23(linker), 512-534(S534A)-(thioester); (c) FP34, 512-545; (d) N36, 546-581(S546C); and (e) N47(L6)C39 aka “Hairpin”, 535(M535C)-581 + non-native SGGRGG loop + 628-666. Chemical syntheses of (a–d) have been previously described and usually included a single directly-bonded 13CO/15N spin pair.51 Hairpin was produced recombinantly in bacteria with subsequent dialysis of the soluble lysate against 0.05% trifluoroacetic acid + 150 μM dithiothreitol, and then filtration and concentration.15,52 All proteins were purified by RP-HPLC and quantitated by (a-d) BCA assay or (e) A280. Mass spectra were consistent with ~95% protein purity.

Native chemical ligation

N70 was prepared by ligating FP34(linker) with N36(S546C) as described previously.51 FP-Hairpin was prepared by ligating FP23(linker) with purified Hairpin at ambient temperature in a solution containing 8 M guanidine hydrocholoride and either 30 mM 4-mercaptophenylacetic acid or 30 mM 2-mercaptoethanesulfonic acid, sodium salt.15 N70 and FP-Hairpin were purified by RP-HPLC and eluted as single peaks and were respectively quantitated using the BCA assay and A280. N70 was lyophilized and FP-Hairpin was dialyzed against Buffer at 4 °C.

Lipid vesicle preparation

Large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs) were prepared in 25 mM HEPES pH 7.4 buffer by extrusion through 100 nm diameter pores. The typical vesicle composition was DTPC:DTPG:cholesterol at 1.6:0.4:1.0 mM which reflects dominant choline headgroup, significant negatively charged lipid, and approximate lipid:cholesterol ratio found in viral and host cell plasma membranes.22 The na 13CO signal was reduced with use of DTPC and DTPG lipids which lack CO nuclei. For membrane-associated HFP, similar FP structure was observed with either ether- or ester-linked lipids.25 FP-Hairpin binds to membranes with this headgroup and cholesterol composition.18

NMR sample preparation

The protein solution was added dropwise to the vesicle suspension which maximized membrane binding of the protein and minimized protein aggregation. The mixture was stirred over the ~1 hour addition time and the pH was maintained above 7 with addition of pH 7.4 buffer. The initial protein solution either contained Buffer with pH ≈ 3 and [protein] = 40 μM (membrane samples), or [protein] = 80 μM and [D-malt] = 9 mM (membrane + D-malt samples). A typical mixture contained [lipid + cholesterol] ≈ 1100 μM and [protein] ≈ 25 μM with ~0.7 μmole protein. The SI provides the specific molar quantity protein and lipid:protein mole ratio for each sample. Proteoliposomes settled during overnight incubation at 4 °C with subsequent centrifugation first at 4000g and then at either 16000 or 100000g. The pellet was transferred to a 4 mm diameter magic angle spinning (MAS) rotor.

General SSNMR

Experiments were done on a 9.4 T (400 MHz) spectrometer (Agilent Infinity Plus, Palo Alto, CA) using a MAS probe in triple resonance 1H/13C/15N configuration for REDOR experiments and double resonance 13C/1H configuration for fpCTDQBU experiments. The 13C shifts were externally referenced to the methylene resonance of adamantane at 40.5 ppm which allows direct comparison with database 13C shifts.53 Samples were cooled with nitrogen gas at −50 °C because relative to ambient temperature, signal-to-noise was improved without changing FP structure.54 The 13C channel was tuned to 100.8 MHz, the 1H channel was tuned to 400.8 MHz, and the 15N channel was tuned to 40.6 MHz. The 1H and 13C rf fields were optimized with polycrystalline samples containing either N-acetyl-leucine (NAL) or GFF tripeptide. NAL was crystallized by slow evaporation of a solution containing doubly 13CO-labeled and unlabeled molecules in a 1:9 ratio and GFF tripeptide was crystallized from doubly 13CO-labeled (G1+F3) and unlabeled molecules in a 1:50 ratio.25,46 The 15N π pulse was optimized using the lyophilized helical “I4” peptide with A9 13CO and A13 15N labels.25

REDOR SSNMR

The REDOR pulse sequence begins with generation of 13C transverse magnetization followed by a dephasing period and then 13C detection. During the 2 ms dephasing period of both the S0r and S1r acquisitions, there was a 13C π pulse at the end of each rotor cycle except the last cycle. For the S1r acquisition, a 15N π pulse was included at the midpoint of each cycle, and the two π pulses per cycle resulted in near-complete attenuation of the signal of directly-bonded 13CO/15N spin pairs. The S0r, S1r and ΔSr = S0r − S1r signals respectively correspond to the total, na, and lab 13CO signals.34 The 13C transmitter shift = 153 ppm, the MAS frequency = 8.0 kHz, and pulse sequence times included: cross-polarization (CP), 1.6 ms; dephasing, 2.0 ms; and recycle delay, 1.0 s. Typical rf fields were: 13C π, 54 kHz; 13C CP ramp, 58–68 kHz; 15N π, 43 kHz; 1H π/2 and CP, 50 kHz; and 1H decoupling, 90 kHz. XY-8 phase cycling was applied to both 15N and 13C π pulses except for the final 13C π pulse. Pulses were calibrated as previously described.25

fpCTDQBU SSNMR

The fpCTDQBU pulse sequence is sequential generation of 13C transverse magnetization, a constant-time period of duration CT split between a variable dephasing period of duration τ and a variable echo period of duration CT − τ, and 13C detection. One finite 13C π pulse per rotor cycle is applied during the CT period; ie. the fpRFDR sequence, and there is a pair of back-to-back 13C π/2 pulses at the midpoints of both the dephasing and the echo periods. For S0f, the phases of the π/2 pulses of each pair are offset by 90° and resulted in refocusing of 13CO-13C dipolar evolution. For S1f, the 90° phase offset is retained for the echo period pair whereas for the dephasing period pair, either 0° or 180° offset is used and results in dipolar evolution during this period and attenuation of the 13CO signal intensity. Because CT is the same for all τ, couplings other than 13CO-13C as well as relaxation could be neglected and the buildup of (S0f − S1f)/S0f = (ΔS/S0)f with τ is attributed to 13CO-13C couplings. The fpCTDQBU pulses were calibrated as previously described and the experiment was verified by good agreement between the (ΔS/S0)f vs τ for NAL and GFF and the (ΔS/S0)f calculated based on the known intramolecular lab 13CO–lab 13CO distances of 3.1 and 5.4 Å, respectively.25,46 Couplings due to intermolecular lab 13CO–lab 13CO distances could be neglected because of dilution with unlabeled molecules.

Typical fpCTDQBU experimental parameters included: MAS frequency = 12.0 kHz; 13C transmitter shift = 163 ppm; 2.0 ms CP; CT = 41.33 ms; 8 ms ≤ τ ≤ 40 ms; 1.5 s recycle delay; 50–60 kHz ramped 13C and constant 56 kHz 1H fields during CP; 22 kHz 13C π pulse and 50 kHz 13C π/2 pulse fields; and 90 and 60 kHz 1H decoupling fields during the CT and acquisition periods, respectively. The (ΔS/S0)fβ and (ΔS/S0)fα were determined from spectral integrations in 1.0 ppm windows centered at the peak β or α shifts. The σ parameter was the root-mean-squared deviation of the intensities of 24 separate 1.0 ppm windows in noise regions of the S0f and S1f spectra. The uncertainty (σexp) in (ΔS/S0)fexp was calculated:

| (4) |

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Fusion peptide structure in membrane-associated gp41

Solid-state NMR measurements of chemical shifts and internuclear proximities

β sheet and α helical fusion peptide populations

Antiparallel β sheet fusion peptides with strand crossing near L7 and F8

Interleaved antiparallel strands from two gp41 trimers show trimer assembly

Acknowledgments

The MSU Mass Spectrometry and NMR facilities are acknowledged. The work was supported by NIH awards R01AI047153 to D.P.W. and F32AI080136 to K.S. We acknowledge Yechiel Shai for tBoc peptide synthesis and cleavage facilities that were partially supported by the Israel Science Foundation.

Abbreviations

- BCA

Bicinchoninic Acid

- Buffer

10 or 20 mM formate at pH 3 + 200 μM TCEP

- chol

cholesterol

- CP

cross-polarization

- D-malt

n-decyl β-D-maltopyranoside

- DTPC

1,2-di-O-tetradecyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- DTPG

1,2-di-O-tetradecyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-rac-(1-glycerol) sodium salt

- FP

fusion peptide

- fpCTDQBU

finite-pulse constant-time double-quantum build-up

- γlab

(S1/S0)f ratio due to nearby lab 13CO nuclei

- γna

(S1/S0)f ratio due to nearby na 13C nuclei

- HEPES

N-(2-Hydroxyethyl) piperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid

- HFP

peptide containing the 23 N-terminal residues of gp41

- lab

labeled

- LUV

large unilamellar vesicle

- MAS

magic angle spinning

- na

natural abundance

- N-PHI

N-terminal region of the PHI

- PHI

pre-hairpin intermediate

- r

internuclear distance

- rll

lab 13CO-lab 13CO internuclear distance

- REDOR

rotational-echo double-resonance

- RP-HPLC

reverse- phase high-performance liquid chromatography

- S0f

fpCTDQBU S0 data and the 13CO signal intensity in the corresponding spectrum

- S1f

fpCTDQBU S1 data and the 13CO signal intensity in the corresponding spectrum

- S0r

REDOR S0 data and the 13CO signal intensity in the corresponding spectrum

- S1r

REDOR S1 data and the 13CO signal intensity in the corresponding spectrum

- SHB

six-helix bundle

- SSNMR

solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance

- ΔSf

S0f − S1f subtracted data and the 13CO signal intensity in the corresponding spectrum

- ΔSr

S0r − S1r subtracted data and the 13CO signal intensity in the corresponding spectrum

- τ

dephasing time

- TCEP

Tris(2-Carboxyethyl) phosphine hydrochloride

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.White JM, Delos SE, Brecher M, Schornberg K. Structures and mechanisms of viral membrane fusion proteins: Multiple variations on a common theme. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;43:189–219. doi: 10.1080/10409230802058320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mao YD, Wang LP, Gu C, Herschhorn A, Xiang SH, Haim H, Yang XZ, Sodroski J. Subunit organization of the membrane-bound HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein trimer. Nature Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:893–899. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu J, Bartesaghi A, Borgnia MJ, Sapiro G, Subramaniam S. Molecular architecture of native HIV-1 gp120 trimers. Nature. 2008;455:109–113. doi: 10.1038/nature07159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tran EEH, Borgnia MJ, Kuybeda O, Schauder DM, Bartesaghi A, Frank GA, Sapiro G, Milne JLS, Subramaniam S. Structural mechanism of trimeric HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein activation. PLOS Pathogens. 2012;8:e1002797. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tan K, Liu J, Wang J, Shen S, Lu M. Atomic structure of a thermostable subdomain of HIV-1 gp41. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12303–12308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caffrey M, Cai M, Kaufman J, Stahl SJ, Wingfield PT, Covell DG, Gronenborn AM, Clore GM. Three-dimensional solution structure of the 44 kDa ectodomain of SIV gp41. EMBO J. 1998;17:4572–4584. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.16.4572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang ZN, Mueser TC, Kaufman J, Stahl SJ, Wingfield PT, Hyde CC. The crystal structure of the SIV gp41 ectodomain at 1.47 A resolution. J Struct Biol. 1999;126:131–144. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1999.4116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sackett K, Wexler-Cohen Y, Shai Y. Characterization of the HIV N-terminal fusion peptide-containing region in context of key gp41 fusion conformations. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:21755–21762. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603135200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freed EO, Delwart EL, Buchschacher GL, Jr, Panganiban AT. A mutation in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmembrane glycoprotein gp41 dominantly interferes with fusion and infectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:70–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.1.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sougrat R, Bartesaghi A, Lifson JD, Bennett AE, Bess JW, Zabransky DJ, Subramaniam S. Electron tomography of the contact between T cells and SIV/HIV-1: Implications for viral entry. PLOS Pathogens. 2007;3:571–581. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Magnus C, Rusert P, Bonhoeffer S, Trkola A, Regoes RR. Estimating the stoichiometry of Human Immunodeficiency Virus entry. J Virol. 2009;83:1523–1531. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01764-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blumenthal R, Durell S, Viard M. HIV entry and envelope glycoprotein-mediated fusion. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:40841–40849. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R112.406272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shu W, Liu J, Ji H, Radigen L, Jiang SB, Lu M. Helical interactions in the HIV-1 gp41 core reveal structural basis for the inhibitory activity of gp41 peptides. Biochemistry. 2000;39:1634–1642. doi: 10.1021/bi9921687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Markosyan RM, Cohen FS, Melikyan GB. HIV-1 envelope proteins complete their folding into six-helix bundles immediately after fusion pore formation. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:926–938. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-09-0573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sackett K, Nethercott MJ, Shai Y, Weliky DP. Hairpin folding of HIV gp41 abrogates lipid mixing function at physiologic pH and inhibits lipid mixing by exposed gp41 constructs. Biochemistry. 2009;48:2714–2722. doi: 10.1021/bi8019492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Durell SR, Martin I, Ruysschaert JM, Shai Y, Blumenthal R. What studies of fusion peptides tell us about viral envelope glycoprotein-mediated membrane fusion. Mol Membr Biol. 1997;14:97–112. doi: 10.3109/09687689709048170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang R, Prorok M, Castellino FJ, Weliky DP. A trimeric HIV-1 fusion peptide construct which does not self-associate in aqueous solution and which has 15-fold higher membrane fusion rate. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:14722–14723. doi: 10.1021/ja045612o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sackett K, TerBush A, Weliky DP. HIV gp41 six-helix bundle constructs induce rapid vesicle fusion at pH 3.5 and little fusion at pH 7.0: understanding pH dependence of protein aggregation, membrane binding, and electrostatics, and implications for HIV-host cell fusion. Eur Biophys J. 2011;40:489–502. doi: 10.1007/s00249-010-0662-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pereira FB, Goni FM, Muga A, Nieva JL. Permeabilization and fusion of uncharged lipid vesicles induced by the HIV-1 fusion peptide adopting an extended conformation: dose and sequence effects. Biophys J. 1997;73:1977–1986. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78228-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gabrys CM, Qiang W, Sun Y, Xie L, Schmick SD, Weliky DP. Solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance measurements of HIV fusion peptide 13CO to lipid 31P proximities support similar partially inserted membrane locations of the α helical and β sheet peptide structures. J Phys Chem A. 2013;117:9848–9859. doi: 10.1021/jp312845w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qiang W, Sun Y, Weliky DP. A strong correlation between fusogenicity and membrane insertion depth of the HIV fusion peptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:15314–15319. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907360106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brugger B, Glass B, Haberkant P, Leibrecht I, Wieland FT, Krasslich HG. The HIV lipidome: A raft with an unusual composition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:2641–2646. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511136103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qiang W, Bodner ML, Weliky DP. Solid-state NMR spectroscopy of human immunodeficiency virus fusion peptides associated with host-cell-like membranes: 2D correlation spectra and distance measurements support a fully extended conformation and models for specific antiparallel strand registries. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:5459–5471. doi: 10.1021/ja077302m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmick SD, Weliky DP. Major antiparallel and minor parallel beta sheet populations detected in the membrane-associated Human Immunodeficiency Virus fusion peptide. Biochemistry. 2010;49:10623–10635. doi: 10.1021/bi101389r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng Z, Yang R, Bodner ML, Weliky DP. Conformational flexibility and strand arrangements of the membrane-associated HIV fusion peptide trimer probed by solid-state NMR spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 2006;45:12960–12975. doi: 10.1021/bi0615902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qiang W, Weliky DP. HIV fusion peptide and its cross-linked oligomers: efficient syntheses, significance of the trimer in fusion activity, correlation of β strand conformation with membrane cholesterol, and proximity to lipid headgroups. Biochemistry. 2009;48:289–301. doi: 10.1021/bi8015668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nieva JL, Agirre A. Are fusion peptides a good model to study viral cell fusion? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1614:104–115. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(03)00168-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Epand RM. Fusion peptides and the mechanism of viral fusion. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1614:116–121. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(03)00169-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lai AL, Moorthy AE, Li YL, Tamm LK. Fusion activity of HIV gp41 fusion domain is related to its secondary structure and depth of membrane insertion in a cholesterol-dependent fashion. J Mol Biol. 2012;418:3–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lakomek NA, Kaufman JD, Stahl SJ, Louis JM, Grishaev A, Wingfield PT, Bax A. Internal dynamics of the homotrimeric HIV-1 viral coat protein gp41 on multiple time scales. Angew Chem. 2013;52:3911–3915. doi: 10.1002/anie.201207266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grasnick D, Sternberg U, Strandberg E, Wadhwani P, Ulrich AS. Irregular structure of the HIV fusion peptide in membranes demonstrated by solid-state NMR and MD simulations. Eur Biophys J. 2011;40:529–543. doi: 10.1007/s00249-011-0676-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sackett K, Nethercott MJ, Epand RF, Epand RM, Kindra DR, Shai Y, Weliky DP. Comparative analysis of membrane-associated fusion peptide secondary structure and lipid mixing function of HIV gp41 constructs that model the early Pre-Hairpin Intermediate and final Hairpin conformations. J Mol Biol. 2010;397:301–315. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gullion T, Schaefer J. Rotational-echo double-resonance NMR. J Magn Reson. 1989;81:196–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang J, Parkanzky PD, Bodner ML, Duskin CG, Weliky DP. Application of REDOR subtraction for filtered MAS observation of labeled backbone carbons of membrane-bound fusion peptides. J Magn Reson. 2002;159:101–110. doi: 10.1016/s1090-7807(02)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gullion T. Introduction to rotational-echo, double-resonance NMR. Concepts Magn Reson. 1998;10:277–289. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murphy OJ, 3rd, Kovacs FA, Sicard EL, Thompson LK. Site-directed solid-state NMR measurement of a ligand-induced conformational change in the serine bacterial chemoreceptor. Biochemistry. 2001;40:1358–1366. doi: 10.1021/bi0015109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang HY, Neal S, Wishart DS. RefDB: A database of uniformly referenced protein chemical shifts. J Biomol NMR. 2003;25:173–195. doi: 10.1023/a:1022836027055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vogel EP, Curtis-Fisk J, Young KM, Weliky DP. Solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy of human immunodeficiency virus gp41 protein that includes the fusion peptide: NMR detection of recombinant Fgp41 in inclusion bodies in whole bacterial cells and structural characterization of purified and membrane-associated Fgp41. Biochemistry. 2011;50:10013–10026. doi: 10.1021/bi201292e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang J, Gabrys CM, Weliky DP. Solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance evidence for an extended beta strand conformation of the membrane-bound HIV-1 fusion peptide. Biochemistry. 2001;40:8126–8137. doi: 10.1021/bi0100283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang J, Prorok M, Castellino FJ, Weliky DP. Oligomeric β-structure of the membrane-bound HIV-1 fusion peptide formed from soluble monomers. Biophys J. 2004;87:1951–1963. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.103.028530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wasniewski CM, Parkanzky PD, Bodner ML, Weliky DP. Solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance studies of HIV and influenza fusion peptide orientations in membrane bilayers using stacked glass plate samples. Chem Phys Lipids. 2004;132:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pan JH, Lai CB, Scott WRP, Straus SK. Synthetic fusion peptides of tick-borne Encephalitis virus as models for membrane fusion. Biochemistry. 2010;49:287–296. doi: 10.1021/bi9017895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yao HW, Hong M. Membrane-dependent conformation, dynamics, and lipid Interactions of the fusion peptide of the paramyxovirus PIV5 from solid-state NMR. J Mol Biol. 2013;425:563–576. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gullion T, Vega S. A simple magic angle spinning NMR experiment for the dephasing of rotational echoes of dipolar coupled homonuclear spin pairs. Chem Phys Lett. 1992;194:423–428. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bennett AE, Weliky DP, Tycko R. Quantitative conformational measurements in solid state NMR by constant-time homonuclear dipolar recoupling. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:4897–4898. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zheng Z, Qiang W, Weliky DP. Investigation of finite-pulse radiofrequency-driven recoupling methods for measurement of intercarbonyl distances in polycrystalline and membrane-associated HIV fusion peptide samples. Magn Reson Chem. 2007;245:S247–S260. doi: 10.1002/mrc.2160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ishii Y. 13C-13C dipolar recoupling under very fast magic angle spinning in solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance: Applications to distance measurements, spectral assignments, and high-throughput secondary-structure determination. J Chem Phys. 2001;114:8473–8483. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sackett K, Shai Y. The HIV fusion peptide adopts intermolecular parallel β-sheet structure in membranes when stabilized by the adjacent N-terminal heptad repeat: A 13C FTIR study. J Mol Biol. 2005;350:790–805. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bodner ML, Gabrys CM, Struppe JO, Weliky DP. 13C-13C and 15N-13C correlation spectroscopy of membrane-associated and uniformly labeled HIV and influenza fusion peptides: Amino acid-type assignments and evidence for multiple conformations. J Chem Phys. 2008;128:052319. doi: 10.1063/1.2829984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harris RB, Wilson IB. Tert-butyl aminocarbonate (tert-butyloxycarbonyloxyamine) - a new acylating reagent for amines. Int J Peptide Protein Res. 1984;23:55–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1984.tb02692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sackett K, Shai Y. The HIV-1 gp41 N-terminal heptad repeat plays an essential role in membrane fusion. Biochemistry. 2002;41:4678–4685. doi: 10.1021/bi0255322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Curtis-Fisk J, Spencer RM, Weliky DP. Isotopically labeled expression in E. coli, purification, and refolding of the full ectodomain of the Influenza virus membrane fusion protein. Protein Expression Purif. 2008;61:212–219. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morcombe CR, Zilm KW. Chemical shift referencing in MAS solid state NMR. J Magn Reson. 2003;162:479–486. doi: 10.1016/s1090-7807(03)00082-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bodner ML, Gabrys CM, Parkanzky PD, Yang J, Duskin CA, Weliky DP. Temperature dependence and resonance assignment of 13C NMR spectra of selectively and uniformly labeled fusion peptides associated with membranes. Magn Reson Chem. 2004;42:187–194. doi: 10.1002/mrc.1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.