Abstract

Bone mineralization is strongly stimulated by weight-bearing exercise during growth and development. Judo, an Olympic combat sport, is a well-known form of strenuous and weight-bearing physical activity. Therefore, the primary goal of this study was to determine the effects of Judo practice on the bone health of male high school students in Korea. The secondary goal of this study was to measure and compare the bone mineral density (BMD) of the hands of Judo players and sedentary control subjects. Thirty Judo players (JDP) and 30 sedentary high school boys (CON) voluntarily participated in the present study, and all of the sedentary control subjects were individually matched to the Judo players by body weight. BMD was determined by using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (Hologic, Bedford, MA, USA). The lumbar spine, femur and forearm BMD in the JDP group were significantly greater by 22.7%, 24.5%, and 18.3%, respectively, than those in the CON group. In addition, a significant difference in the CON group was observed between the dominant hand (DH) radius (0.710 ± 0.074 g/cm2) and the non-dominant hand (NDH) radius (0.683 ± 0.072 g/cm2), but this was not observed in the JDP group (DH = 0.819 ± 0.055 g/cm2; NDH = 810 ± 0.066 g/cm2) (P < 0.05). Therefore, the results of this study suggest that Judo practice during the growth period significantly improves bone health in high school male students. In addition, it seems that Judo practice could eliminate the effect of increased BMD in the dominant hand.

Keywords: judo, bone mineral density, dominant hand

INTRODUCTION

A decrease in physical activity may lead to an increased loss of bone mineralization, and the increasing incidence of bone fractures is a major modern medical problem [6, 30]. Attaining maximal peak bone mass during the growth period, as well as minimizing bone mineral loss due to aging, is an important strategy for the prevention of osteoporosis and bone fractures. The greatest accumulation of bone mass occurs during the first and second decades of life, and bone mass peaks around the age of 20 years [27]. Therefore, the first two decades of life may play an important role in preventing fractures and enhancing lifetime bone health.

In previous studies, skeletal loads including dynamic loads, high magnitude loads, high frequency loads, fast loads and loads with unusually distributed strains have been shown to constitute the most pronounced osteogenic stimuli [24, 28]. Judo, Taekwondo, Tai-Chi and Karate, which are all forms of martial art that are also considered to be a form of strenuous physical activity and weight-bearing exercise, have been reported to stimulate the osteogenic process and improve bone health [1, 23, 26]. Longitudinal training studies have also indicated that strength training and high-impact endurance training increase bone density [2, 21]. However, few investigators have evaluated the effects of Judo activity on bone health.

As an Olympic combat sport, Judo involves both high intensity and high strain rates, which strongly stimulate bone formation. Specifically, unusual strain distribution and versatile loading patterns, which are both involved in the practice of Judo, promote increased bone mineralization more than exercises that involve regular loading patterns [7]. Both BMC and BMD in Judo players have been reported to be significantly higher compared to those in sedentary control subjects [1, 22]. Thus, Judo may have optimal osteogenic potential in both upper and lower extremities as specific strain-related variables are integrated into the dynamic loading conditions of Judo. The BMD in the arm region of Judo players has been reported to be significantly greater than that of sedentary control subjects [1]. However, in this study, the effect of hand dominance was not separately determined in Judo players and sedentary controls even though it is reported that a side-to-side difference of BMD of the hand is normally observed in sedentary subjects [8, 15, 29, 32].

Hand dominance along with associated unilateral loading, such as in tennis players, results in greater bone mineral content, bone mineral density and bone area in the upper extremity of the dominant hand [5, 25]. Differential increase in bone mass between lower extremities can also be observed in specific training [29, 32]. It is generally agreed that side-to-side differences of bone mass measurements in sedentary subjects are usually lower than in athletes [8, 15, 29, 32]. In sedentary subjects, the side-to-side differences between the upper extremities can vary up to 6.4% for BMC and up to 4.6% for BMD, although the extent of these side-to-side differences varies among sub-regions of the extremity [8, 15]. The side-to-side differences in BMC and BMD measurements between lower extremities were not detected in the literature [29, 32] with the exception of one report that showed that hip BMD was 8.1% greater on the dominant side than the non-dominant side [10]. However, it is necessary to examine side-to-side difference in BMD of Judo players since both hands are equally involved in Judo training.

Therefore, the primary goal of this study was to determine the effects of Judo training on bone health in Korean male high school students. The secondary goal of this study was to test the hypothesis that BMD of the forearm is greater in the extremity that corresponds to the side of the dominant hand. The information gained from this study will allow researchers and clinicians to better understand the effects of Judo training on male bone health.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

The study subjects were male high school students in Daegu, Korea. Thirty boys who had undergone between 3 and 10 years in Judo training (JDP) participated in this study, and 30 sedentary boys who had not experienced any extra-curriculum activities in school or home served as control subjects (CON). None of the participants had notable medical problems. Written informed consent was obtained from all of the subjects. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Kyungpook National University. Table 1 presents all of the participant characteristics.

TABLE 1.

SUBJECT CHARACTERISTICS

| CON | JDP | |

|---|---|---|

| Chronological Age (yr) | 17.2±1.2 | 17.2±0.6 |

| Height (cm) | 175.0±3.3 | 174.5±3.9 |

| Body weight (kg) | 72.5±4.6 | 75.8±4.3 |

| Exercise Career (yr) | - | 5.7±2.5 |

| BMI (kg · m-2) | 23.7±1.7 | 24.9±1.7 |

| Exercise Volume (hr · weeks-1) | - | 10.5±1.5 |

Note: Data are shown as mean ± SD. Sedentary high school boys, CON; Judo players, JDP. Body Mass Index, BMI

Bone mass measurements

We conducted the health examinations for this study in the Spring of 2012. The forearm, lumbar and femoral BMD were measured using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (Hologic, Bedford, MA, USA).

Measurement precision, which is expressed as the coefficient of variation (CV), of the BMD measurements was 1.26% for the ulna, 1.73% for the radius, 0.89% for the lumbar spine and 1.97% for the femur.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SE. Two-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test the mean difference between the dominant and non-dominant hands. The sphericity assumption was justified by using the paired t-test within subjects, and the independent t-test between groups was also performed. P values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

BMD in the lumbar spine

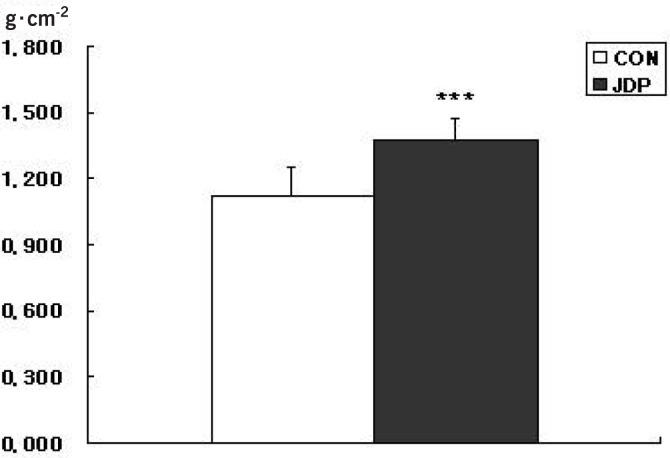

Figure 2 shows that the JDP group (1.374 ± 0.129 g · cm-2) had a total lumbar spine BMD that was significantly greater than that of the CON group (1.119 ±0.096 g ·cm-2, P < 0.001). The average BMD values of all of the lumbar spine regions in the JDP group were significantly higher than in the CON group (P < 0.001) (Table 2).

FIG. 1.

BMD OF THE LUMBAR SPINE

Note: Sedentary high school boys, CON; Judo players, JDP. Data are shown as mean ± SD. ***P < 0.001 versus CON.

TABLE 2.

BONE MINERAL DENSITY OF THE LUMBAR SPINE (g · cm-2)

| CON | JDP | |

|---|---|---|

| L1 | 1.039 ± 0.124 | 1.263 ± 0.081*** |

| L2 | 1.111 ± 0.144 | 1.390 ± 0.100*** |

| L3 | 1.159 ± 0.134 | 1.425 ± 0.104*** |

| L4 | 1.153 ± 0.129 | 1.139 ± 0.126*** |

Note: Data are shown as mean ± SD. Sedentary high school boys, CON; Judo players, JDP. Lumbar 1, L1; Lumbar 2, L2; Lumbar 3, L3; Lumbar 4, L4.

P < 0.001 versus CON

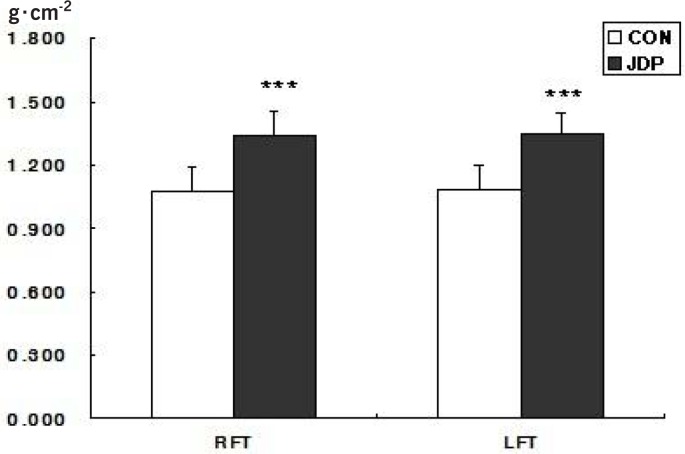

FIG. 2.

BMD OF THE FEMUR

Note: Sedentary high school boys, CON; Judo players, JDP. Right femur total, RFT; Left femur total, LFT. Data are shown as mean ± SD. ***P < 0.001 versus CON.

BMD in the femur

Figure 2 shows that the JDP group (right: 1.340 ± 0.117, left: 1.346 ± 0.102 g · cm-2) had significantly greater total femur BMD than the CON group (right: 1.074 ± 0.115, left: 1.084 ± 0.114 g · cm -2, P < 0.001). The average BMD of the femur regions of the JDP group was significantly higher than in the CON group (P < 0.001)(Table 3). However, the BMD values of the right and left femurs in the CON and the JDP groups were not significantly different.

TABLE 3.

BONE MINERAL DENSITY OF THE FEMUR (g · cm-2)

| CON | JDP | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Neck | Right | 1.086 ± 0.118 | 1.334 ± 0.106*** |

| Left | 1.089 ± 0.116 | 1.374 ± 0.141*** | |

| Wards | Right | 0.980 ± 0.141 | 1.333 ± 0.125*** |

| Left | 0.984 ± 0.140 | 1.350 ± 0.173*** | |

| Troch | Right | 0.882 ± 0.112 | 1.130 ± 0.101*** |

| Left | 0.893 ± 0.114 | 1.147 ± 0.104*** |

Note: Data are shown as mean ± SD. Sedentary high school boys, CON; Judo players, JDP.

P < 0.001 versus CON

BMD in the forearm

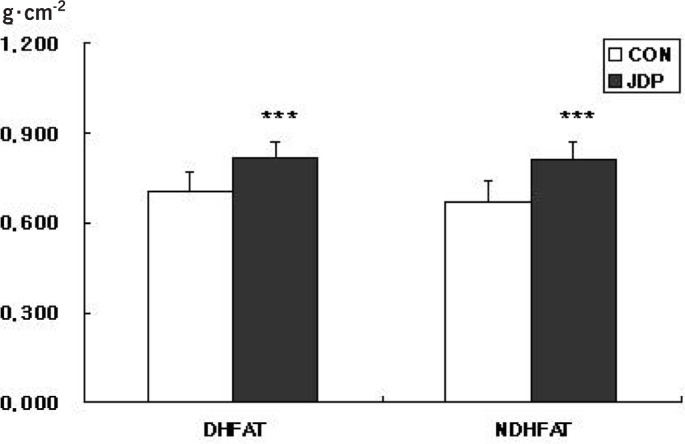

Figure 3 shows that the JDP group (dominant hand forearm total [DHFAT]: 0.816 ± 0.057, non-dominant hand forearm total [NDHFAT]: 0.807 ± 0.065 g · cm-2) had a significantly higher total forearm BMD than the CON group (DHFAT: 0.701 ± 0.057, NDHFAT: 0.671 ± 0.065 g · cm-2, P < 0.001). The average BMD values of the radius and ulna regions of the JDP group were also significantly greater than in the CON group (P < 0.001) (Table 4). The total BMD of the forearm and ulna in the CON group was not significantly different between the dominant hand and the non-dominant hand, but the average BMD of the radius was significantly lower in the non-dominant hand than in the dominant hand (P < 0.05). However, the BMD of the forearm in the JDP group was not statistically different between the non-dominant hand and the dominant hand.

FIG. 3.

BMD OF THE LUMBAR SPINE

Note: Sedentary high school boys, CON; Judo players, JDP. Dominant hand forearm total, DHFAT; Non-dominant hand forearm total, NDHFAT. Data are shown as mean ± SD. ***P < 0.001 versus CON

TABLE 4.

BONE MINERAL DENSITY OF THE FOREARM (g · cm-2)

| CON | JDP | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ulna | DN | 0.690 ± 0.068 | 0.812 ± 0.069*** |

| NDH | 0.654 ± 0.059 | 0.804 ± 0.071*** | |

| Radius | DH | 0.710 ± 0.074 | 0.819 ± 0.055*** |

| NDN | 0.683 ± 0.072* | 0.810 ± 0.066*** |

Note: Data are shown as mean ± SD. Sedentary high school boys, CON; Judo players, JDP. Dominant hand, DH; Non-dominant hand, NDH.

P < 0.001 versus CON.

p < 0.05 versus DH

DISCUSSION

Weight-bearing exercise has been shown to improve bone health when performed during the adolescent period [18, 9]. Several studies have demonstrated an association between vigorous exercise and BMD at various body sites [17, 20, 19]. It has been suggested that vigorous physical activity affects the skeleton, BMC and BMD in an anabolic manner [11]. However, high-school boys who currently attend school in Korea are subjected to a few daily vigorous physical activities as they focus instead on preparation for the Korea University Entrance Examination, and this lack of activity may have an influence on their bone formation. Eight of our sedentary subjects who were randomly selected for this study were borderline for osteopenia (data not shown). In the current study, the boys who had engaged in Judo practice had greater BMD in their lumbar, femur, and wrist regions when compared with their non-active peers, because they have practised Judo for 3 to 10 years (average = 5.7+/-2.5 years). In addition, no side-to-side difference in BMD of the wrist region was found at the distal radius of Judo players, but an approximate 3.8% difference did exist in the control subjects.

According to the results of this study, the BMD was approximately 22.7% higher in the lumbar spine, 24.5% higher in the femur and 18.3% higher in the forearm of Judo players when compared to the sedentary controls. The mechanical load required to stimulate osteogenesis decreases as the strain magnitude and frequency increase [4, 12]. The osteogenic response to high magnitude loading saturates after a few loading cycles, after which additional loading has limited benefits [17]. Thus, high intensity sports, such as squash, tennis, soccer, ice hockey, badminton, volleyball and weight-lifting, are most effective when performed periodically, at different times throughout the week, if the aim is to improve skeletal strength [17]. Based on the results of these studies and the present study, we strongly recommend intermittent Judo activity to increase BMD in high-school-aged boys.

Fracture frequency is generally related to bone mass [31]. The higher fracture rates of the non-dominant forearm that have been reported in epidemiological studies [3] may be explained in part by lower bone mass since the BMC is lower in the non-dominant extremity compared to that of the dominant forearm. BMC is 25–35% higher in the dominant arms of professional tennis players compared to the non-dominant arms [14]. Furthermore, life-long tennis players aged 70–84 years exhibited 4–7% higher BMC in their dominant forearm compared to their non-dominant forearm [13]. Both male and female gymnasts, soccer players, weight-lifters and ballet dancers are reported to have 10–25% higher BMCs than non-exercising controls [18, 9, 17, 16]. In the current study, the BMD difference was 18.3% between the JDP and CON group. Also, a 3.8% difference in BMD existed between the distal radii of the two hands of the sedentary controls, but this was not observed in the Judo players. Thus, we suggest that this difference between the two hands of the sedentary controls may partially explain the higher fracture rates of the non-dominant hand.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, Judo practice significantly enhances bone health during the growth period of adolescent males. The BMD between the dominant and non-dominant hands was not significantly different in Judo players, but there was an approximate 3.8% difference in BMD when side-to-side hand comparisons were performed in the sedentary controls. Therefore, Judo activity is strongly recommended to improve bone health and prevent osteopenia in young Korean males. Additional well-designed investigations of the relationship between Judo activity and bone health across age groups and gender are warranted.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andreoli A, Monteleone M, Van Loan M, Promenzio L, Tarantino U, De Lorenzo A. Effects of different sports on bone density and muscle mass in highly trained athletes. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2001;33:507–511. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200104000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bennell K.L, Malcolm S.A, Khan K.M, Thomas S.A, Reid S.J, Brukner P.D, Ebeling P.R, Wark J.D. Bone mass and bone turnover in power athletes, endurance athletes, and controls: a 12-month longitudinal study. Bone. 1997;20:477–484. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(97)00026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borton D, Masterson E, O'Brien T. Distal forearm fractures in children: the role of hand dominance. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 1994;14:496–497. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199407000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cullen D.M, Smith R.T, Akhter M.P. Bone-loading response varies with strain magnitude and cycle number. J. Appl. Physiol. 2001;91:1971–1976. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.5.1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ducher G, Tournaire N, Meddahi-Pelle A, Benhamou C.L, Courteix D. Short-term and long-term site-specific effects of tennis playing on trabecular and cortical bone at the distal radius. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2006;24:484–490. doi: 10.1007/s00774-006-0710-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eickhoff J.A, Molczyk L, Gallagher J.C, De Jong S. Influence of isotonic, isometric and isokinetic muscle strength on bone mineral density of the spine and femur in young women. Bone Miner. 1993;20:201–209. doi: 10.1016/s0169-6009(08)80001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frost H.M. Muscle, bone, and the Utah paradigm: a 1999 overview. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2000;32:911–917. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200005000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haapasalo H, Kannus P, Sievanen H, Heinonen A, Oja P, Vuori I. Long-term unilateral loading and bone mineral density and content in female squash players. Calcif. Tissue Int. 1994;54:249–255. doi: 10.1007/BF00295946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hara S, Yanagi H, Amagai H, Endoh K, Tsuchiya S, Tomura S. Effect of physical activity during teenage years, based on type of sport and duration of exercise, on bone mineral density of young, premenopausal Japanese women. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2001;68:23–30. doi: 10.1007/BF02684999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henderson R.C. Assessment of bone mineral content in children. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 1991;11:314–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hind K, Burrows M. Weight-bearing exercise and bone mineral accrual in children and adolescents: a review of controlled trials. Bone. 2007;40:14–27. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsieh Y.F, Turner C.H. Effects of loading frequency on mechanically induced bone formation. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2001;16:918–924. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.5.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huddleston A.L, Rockwell D, Kulund D.N, Harrison R.B. Bone mass in lifetime tennis athletes. JAMA. 1980;244:1107–1109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones H.H, Priest J.D, Hayes W.C, Tichenor C.C, Nagel D.A. Humeral hypertrophy in response to exercise. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1977;59:204–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kannus P, Haapasalo H, Sievanen H, Oja P, Vuori I. The site-specific effects of long-term unilateral activity on bone mineral density and content. Bone. 1994;15:279–284. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(94)90289-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karlsson M.K, Hasserius R, Obrant K.J. Bone mineral density in athletes during and after career: a comparison between loaded and unloaded skeletal regions. Calcif. Tissue Int. 1996;59:245–248. doi: 10.1007/s002239900117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karlsson M.K, Nordqvist A, Karlsson C. Physical activity increases bone mass during growth. Food Nutr. Res. 2008;52 doi: 10.3402/fnr.v52i0.1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kriemler S, Zahner L, Puder J.J, Braun-Fahrlander C, Schindler C, Farpour-Lambert N.J, Kranzlin M, Rizzoli R. Weight-bearing bones are more sensitive to physical exercise in boys than in girls during pre-and early puberty: a cross-sectional study. Osteoporos. Int. 2008;19:1749–1758. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0611-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morris F.L, Naughton G.A, Gibbs J.L, Carlson J.S, Wark J.D. Prospective ten-month exercise intervention in premenarcheal girls: positive effects on bone and lean mass. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1997;12:1453–1462. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.9.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petit M.A, Hughes J.M, Wetzsteon R.J, Novotny S.A, Warren M. Re: weight-bearing exercise and bone mineral accrual in children and adolescents: a review of controlled trials. Bone. 2007;41:903–905. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pollock M.L, Mengelkoch L.J, Graves J.E, Lowenthal D.T, Limacher M.C, Foster C, Wilmore J.H. Twenty-year follow-up of aerobic power and body composition of older track athletes. J. Appl. Physiol. 1997;82:1508–1516. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.82.5.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prouteau S, Pelle A, Collomp K, Benhamou L, Courteix D. Bone density in elite judoists and effects of weight cycling on bone metabolic balance. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2006;38:694–700. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000210207.55941.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qin L, Choy W, Leung K, Leung P.C, Au S, Hung W, Dambacher M, Chan K. Beneficial effects of regular Tai Chi exercise on musculoskeletal system. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2005;23:186–190. doi: 10.1007/s00774-004-0559-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rubin C.T, Lanyon L.E. Regulation of bone mass by mechanical strain magnitude. Calcif. Tissue Int. 1985;37:411–417. doi: 10.1007/BF02553711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sanchis-Moysi J, Dorado C, Olmedillas H, Serrano-Sanchez J.A, Calbet J.A. Bone and lean mass inter-arm asymmetries in young male tennis players depend on training frequency. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 110:83–90. doi: 10.1007/s00421-010-1470-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shin Y.H, Jung H.L, Kang H.Y. Effects of taekwondo training on bone mineral density of high school girls in Korea. Biol. Sport. 2011;28:195–198. doi: 10.5604/20831862.1077556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teegarden D, Proulx W.R, Martin B.R, Zhao J, McCabe G.P, Lyle R.M, Peacock M, Slemenda C, Johnston C.C, Weaver C.M. Peak bone mass in young women. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1995;10:711–715. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650100507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Turner C.H, Woltman T.A, Belongia D.A. Structural changes in rat bone subjected to long-term, in vivo mechanical loading. Bone. 1992;13:417–422. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(92)90084-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vuori I, Heinonen A, Sievanen H, Kannus P, Pasanen M, Oja P. Effects of unilateral strength training and detraining on bone mineral density and content in young women: a study of mechanical loading and deloading on human bones. Calcif. Tissue Int. 1994;55:59–67. doi: 10.1007/BF00310170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang M.C, Dixon L.B. Socioeconomic influences on bone health in postmenopausal women: findings from NHANES III, 1988-1994. Osteoporos. Int. 2006;17:91–98. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-1917-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wasnich R. Bone mass measurement: prediction of risk. Am. J. Med. 1993;95:6S–10S. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(93)90374-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu J, Ishizaki S, Kato Y, Kuroda Y, Fukashiro S. The side-to-side differences of bone mass at proximal femur in female rhythmic sports gymnasts. J. Bone. Miner Res. 1998;13:900–906. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.5.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]