Abstract

The axe kick, in Olympic style taekwondo, has been identified as the most popular scoring technique aimed to the head during full contact competition. The first purpose of this study was to identify and investigate design issues with the current World Taekwondo Federation approved chest protector. A secondary purpose was to develop a novel chest protector addressing the identified design issues and to conduct a biomechanical analysis. Fifteen male elite Taekwondo players were selected to perform three different styles of the axe kick, i.e., front, in-out, and out-in axe kick five times each for a total of 45 kicks. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA showed significant differences between the novel and existing chest protector conditions for vertical height of the toe, downward kicking foot speed, hip flexion angle and ipsilateral shoulder flexion extension range of motion (ROM) (p < 0.05). There were no significant differences between the control condition (no chest protector) and the novel chest protector condition for these variables (p > 0.05). These results indicate that the novel chest protector interferes less with both the lower and upper limbs during the performance of the axe kick and provides a more natural, free-moving alternative to the current equipment used.

Keywords: axe kick, novel chest protector, taekwondo

INTRODUCTION

According to the World Taekwondo Federation (WTF) there are more than 80 million [8] practitioners of Taekwondo (TKD) in 200 countries [14]. The WTF has amended earlier rules [15] to now allow four points for successful spinning kicks to the head. As a direct result it has been recently demonstrated, in a study of the techniques used in the WTF finals from 2001 to 2011, that there has been an increase in the number of kicks executed by athletes to the head [5]. Koh and Cassidy [6], in a study of the incidence of concussions in TKD competitions, concluded that the most common head strikes observed in competitions in Korea were the axe kick, roundhouse kick, back kick and spinning hook kick.

The axe kick has been shown to be a highly effective offensive and defensive scoring technique [6, 11] and its purpose is to attack an opponent's head with a powerful downward force [13]. In Koh and Watkinson's study [7], from a total sample of 1652 males and 676 females, 51.4% of head blows were by the axe kick, followed by the roundhouse kick, (25.7%). The sequential movements during the axe kick include the knee raising in an upward in-to-out or out-to-in arc motion. Another variation to this kick involves the simple raising of the leg straight up and down in front of the body, where the leg is extended above the target and pulled down onto the target [1]. Because the axe kick motion requires the kicking foot to be raised higher than the intended target, the angle created at the hip joint is found to require a substantially large range of motion [11].

Various studies have been carried out about different aspects of the chest protector in taekwondo, focusing on protective qualities [3, 4, 9] and the introduction of the electronic scoring protector system [2]. The first published study [9] investigated the protective qualities of the chest protector in taekwondo for various swing-like kicks and push-like kicks. The authors demonstrated that without a chest protector, a kick to the chest can induce thoracic deflections up to 5 cm and peak viscous tolerance values of up to 1.4 m · s−1. This means that if a player is to receive a kick unprotected, there is a high probability of serious injury. Similarly, there have been two further studies investigating the protective function of the chest protector [3, 4]. Chi et al. [2] report on the use of wireless force sensing chest protectors and their role in improving judging in taekwondo competition. However, there have been no published studies that examine the ergonomic difficulties of having to wear a chest protector during competition.

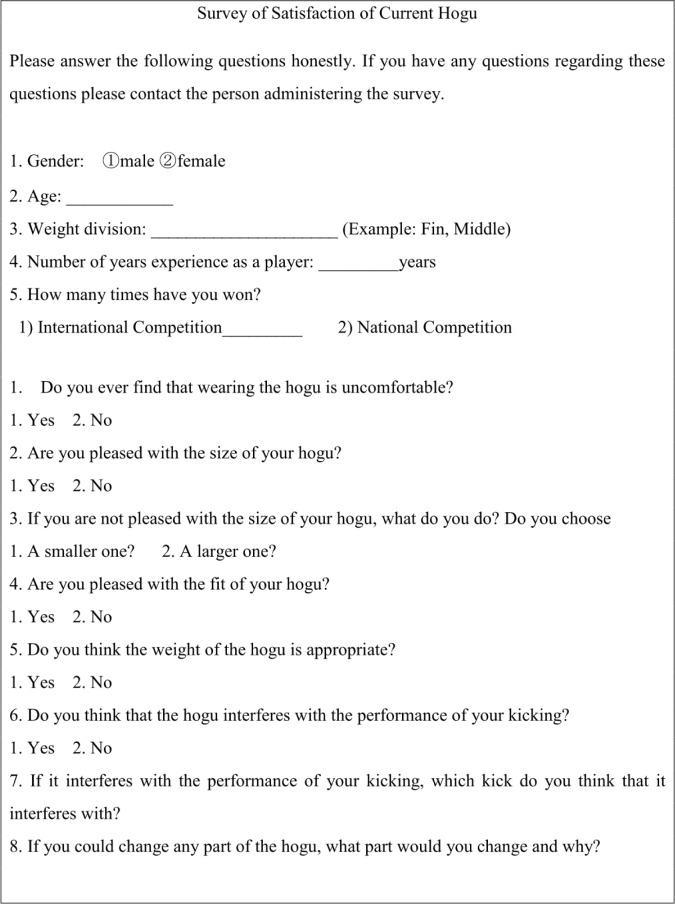

At the 2011 Gyungju World Taekwondo Competition the authors surveyed the 56 Korean professional players (age: 21.8 ± 2.21 years) using the provided satisfaction survey of the chest protector (Figure 1). Over 96% of the players agreed with the statement that the current chest protector interferes with kicking to the head. When the players were asked about which kick in particular the chest protector interfered with, over 91% indicated the axe kick. To investigate whether the chest protector was really interfering with the performance of the axe kick the following variables were recorded: maximum vertical height of the toe, maximum downward kicking foot speed, hip flexion (relative angle between the trunk and the thigh), ipsilateral shoulder flexion-extension range of motion and ipsilateral shoulder extension pulling speed.

FIG. 1.

SURVEY OF EXISTING CHEST PROTECTOR

FIG. 2.

DIMENSIONS OF NEW HOGU

FIG. 3.

STANDARD SIZE 3 EXISTING CHEST PROTECTOR

TABLE 1.

DIFFERENCES IN HOGU DIMENSIONS

| Official Specifications | New Hogu | |

|---|---|---|

| Official Size | 3 | 3 |

| Recommended Weight Range (kg) | 51∼63 | 51∼63 |

| A Chest circumference (cm) | 98 | 94 |

| B Length from naval to sternum (cm) | 47.5 | 35.9 |

| C Closure length (cm) | 29.5 | 25 |

| D Shoulder width (cm) | 15 | 14 |

| E Centre of side length (cm) | 29.5 | 20.3 |

The purpose of this study was to discover functional performance limitations associated with using the current WTF approved chest protector and to modify the chest protector to fit more ergonomically to enhance axe kick functional kicking performance. The final objective was to evaluate the effect of this modified chest protector on biomechanical kicking parameters, in comparison to two other kicking conditions: wearing the WTF approved chest protector, and a control condition (no chest protector).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Development of novel chest protector

Prior to the change in design of the existing chest protector the authors carried out a survey about the satisfaction level of the chest protector among the national team player squad in Korea. Fifty-six of these professional players completed the questionnaire which included closed and open-ended questions (Figure 1). When asked if the chest protector interferes with kicking to the head, over 96% of the players indicated that it was a limiting factor, and 91% of these respondents indicated that the axe kick was the most restricted technique. These responses provided the basis for the follow through study involving the development and assessment of the ergonomic ecology of the design.

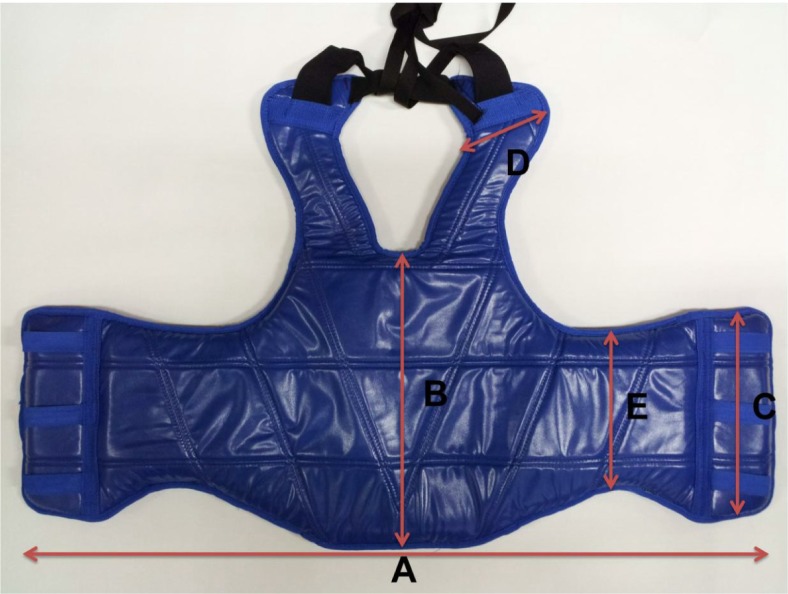

For sizing of the chest protector, the height, weight, chest circumference, waist front length, front interscye field length, back interscye field length, closure length (iliac crest to scapular inferior angle), shoulder width, neck-clavicle length (first rib to inferior part of the clavicle) and clavicle length of 20 Taekwondo players were measured using a vernier calipers (NA500-300s, 600s, Bluebird, Korea). The male (54-62 kg) and female (51-62 kg) players surveyed all used the officially approved size 3. These measurements were performed both in a standing position and in a standard fighting position. The measurement changes were based on the measurements shown in The following changes were applied to the dimensions of the chest protector as a result of the anthropometric measurements and comments from the survey. The 95th percentile was used for the fitting as the 50th percentile was suggested to be too small [16]. With the original chest protector 2 cm above the clavicle, the athletes tended to pull or move the chest protector down approximately 8 cm. This 8 cm was measured between before and after the players adjusted the chest protector for comfort. As a result of the players moving the chest protector down, it began to interfere with their kicking and as they kicked the chest protector would slide back up, hitting their neck. Therefore to prevent the players from repositioning their chest protector to a lower position the straight neck part was changed to a V-neck. During competition, dynamic trunk positions (e.g., trunk flexion) force the clavicle to navel distance to be shortened by 6.0 cm to 35.9 cm. This altering of the clavicle-navel distance indicates that the chest protector is too long, thus interfering with the hip range of motion during various kicking techniques. Side dimensions (C, D and E) were shortened to allow for more movement of the scapula and more natural arm movement. The sides were curved to follow more movement for both the legs and the arms accordingly. The lower parts were shorted to follow the arc above the iliac crest and the higher parts were shortened to follow the natural curve of the scapula (Figure 4).

FIG. 4.

COMPARISON OF TWO CHEST PROTECTORS (NEW CHEST PROTECTOR ABOVE)

In addition, the standard chest protector is made out of 1.0 cm of polyester sponge and 1.5 cm of ethylene vinyl acetate copolymer for shock absorption. To increase the pliability and comfort, the padding was changed to two sheets of memory foam (width = 0.5 cm). Two sheets of ethylene vinyl acetate copolymer (width = 0.5 cm) were covered with one sheet of toilon (width = 0.5 cm). A rubber band was also used to fix the chest protector as close as possible to the body for extra comfort.

Participants

Fifteen elite collegiate level taekwondo players (mass 59.4 ± 4.3 kg, height 1.71 ± 0.04 m, leg length 0.84 ± 0.03 m) were recruited. Each of these elite participants reported over ten years of experience in taekwondo. Participants suffering from any musculoskeletal injury within the last two years were excluded.

Experimental procedure

Participants completed an informed consent form approved by the Hallym University Institutional Review Board held in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. After completion of the informed consent form, subjects were instructed to warm up by performing a combination of ten jumping jacks and light static stretching of the following muscles: quadriceps, biceps femoris, soleus, gastrocnemius, external abdominal obliques, erector spinae. In total the warm-up took approximately 10 minutes. After this warm-up, reflective markers were fixed to the relevant landmarks via double sided tape. Each of the participants was instructed to perform each kick five times for each condition. Each player executed a total of 45 kicks, 15 kicks for each condition, 5 in-out axe kicks, 5 out-in axe kicks and 5 straight axe kicks for each of the chest protector conditions. Conditions consisted of wearing the standard WTF approved chest protector, our novel chest protector, and the control condition (no chest protector). All kicks and chest protector conditions were randomized prior to testing and subjects were unaware of the order until execution of each kick and introduction of each condition. For each of the conditions maximum vertical height of the toe, maximum downward kicking foot speed, hip flexion (relative angle between the trunk and the thigh), ipsilateral shoulder flexion-extension range of motion and ipsilateral shoulder extension pulling speed were measured.

Data collection and statistical analysis

Kinematic data were recorded by eight Qualisys cameras (OQUS 100, Sweden) at a frequency of 150 Hz. Cameras were synchronized and reflective markers were manually labelled using QTM (Qualisys Track Manager, Sweden). All data were exported as a C3D file and processed and filtered by a second order Butterworth filter at 15 Hz using Visual3D version 4.01 (C-motion, Germantown, MD, USA). Repeated measures ANOVA was used to detect differences between the three conditions and independent variables. The level of significance was set at 0.05.

Terminology

Chest protector is the standard protective chest guard which must be worn by all athletes that are participating in Olympic style TKD competitions sanctioned by the WTF.

Leg length is measured from the marker on the anterior superior inferior spine (ASIS) to the marker on the medial malleolus.

Vertical height of the toe is measured by the maximum height in the z-axis from the positional data of the reflexive marker on the kicking foot's head of the fifth metatarsal.

Downward kicking foot speed is measured from the speed of the marker on the fifth metatarsal in the downward direction, i.e. after the foot has reached its maximum height to impact.

Hip flexion is the relative angle measured between the thigh segment and the trunk segment.

Ipsilateral shoulder flexion-extension range of motion is measured during the axe kick from the point of maximum flexion of the upper arm to the maximum extension of the upper arm.

Ipsilateral shoulder extension pulling speed is the measured speed at the distal end speed of the upper arm segment.

RESULTS

Table 2 displays the descriptive statistics and results of the two-way 3 (chest protector condition) x 3 (kick type) repeated measures ANOVA performed on the variables. There were no significant interactions between the kick type and the chest protector condition. There were significant main effects (p < 0.05; refer to Table 2) recorded between the chest protector conditions for all variables except the ipsilateral shoulder extension pulling speed for the straight axe kick. Post hoc analyses using the Bonferroni post hoc criterion were used to show significant differences within the groups. Results of the post-hoc analyses are also included in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

COMPARISON OF INDEPENDENT VARIABLES BY THE TYPES OF CHEST PROTECTOR (N = 15)

| CP types | Height (m) | Foot speed (m·s−1) | Hip flexion (°) | Shoulder ROM (°) | Shoulder speed (m·s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Front axe kick | |||||

| CPno | 1.76 ± 0.052 | 7.91 ± 1.102 | 146.98 ± 34.502 | 71.83 ± 16.182 | 2.70 ± 0.78 |

| CPe | 1.72 ± 0.051,3 | 7.22 ± 0.831,3 | 140.01 ± 32.521,3 | 60.45 ± 21.161,3 | 2.35 ± 0.40 |

| CPn | 1.75 ± 0.052 | 7.84 ± 0.982 | 145.11 ± 32.912 | 69.67 ± 22.542 | 2.63 ± 0.51 |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.003 | 0.010 | 0.080 |

| F | 10.417 | 17.818 | 7.413 | 5.512 | 3.082 |

| effect size | 0.427 | 0.733 | 0.346 | 0.282 | - |

| In-out axe kick | |||||

| CPno | 1.74 ± 0.052 | 7.72 ± 0.572 | 150.95 ± 34.502 | 71.45 ± 16.222 | 3.00 ± 0.83 |

| CPe | 1.69 ± 0.061,3 | 7.24 ± 0.691,3 | 140.12 ± 33.111,3 | 63.24 ± 15.811,3 | 2.57 ± 0.573 |

| CPn | 1.73 ± 0.052 | 7.70 ± 0.842 | 146.81 ± 32.282 | 69.36 ± 19.692 | 2.94 ± 0.652 |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.014 | 0.010 |

| F | 36.220 | 17.546 | 15.298 | 5.022 | 6.715 |

| effect size | 0.721 | 0.556 | 0.522 | 0.264 | 0.508 |

| Out-in axe kick | |||||

| CPno | 1.72 ± 0.052 | 7.41 ± 0.732 | 145.55 ± 32.402 | 68.93 ± 23.952 | 2.93 ± 0.562 |

| CPe | 1.69 ± 0.061,3 | 6.87 ± 0.581,3 | 135.75 ± 33.671,3 | 57.75 ± 25.301,3 | 2.44 ± 0.401,3 |

| CPn | 1.71 ± 0.052 | 7.34 ± 0.742 | 143.94 ± 32.022 | 68.39 ± 24.102 | 2.87 ± 0.512 |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.003 | <0.001 | 0.006 |

| F | 12.270 | 13.460 | 9.765 | 12.189 | 7.891 |

| effect size | 0.467 | 0.490 | 0.600 | 0.465 | 0.548 |

Note: CP = chest protector; CPno = no chest protector; CPe = existing chest protector; CPn = novel chest protector; Height = maximum vertical height of the toe; Foot speed = maximum downward kicking foot speed; Shoulder ROM = ipsilateral shoulder flexion-extension range of motion; Shoulder speed = ipsilateral shoulder extension pulling speed.

Significantly different compared with CPno

Significantly different compared with CPe

Significantly different compared with CPn

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to compare the effects of a modified chest protector and those of a standard chest protector on axe kick performance. Results of the Korean Taekwondo National Team players’ responses to the survey indicated that existing chest protectors interfere with performance of the axe kick. Based on these results of the satisfaction survey, the chest protector was redesigned to be more flexible and not to interfere with kicks aimed to the head. The main changes to the chest protector included the change of padding material and layering to improve pliability and to narrow the side protection as it restricted thigh and upper arm movements. The effects of these modifications on vertical height of the kicking toe, downward kicking foot speed, hip flexion, ipsilateral shoulder flexion-extension ROM, and ipsilateral shoulder extension pulling speed, compared to the standard WTF approved chest protector and the control condition, were analyzed. The downward kicking foot speed of the straight axe kick before impact for the control group, the WTF approved protector group, and the novel chest protector group was 7.91 ± 1.10 m · s−1, 7.22 ± 0.83 m · s−1, and 7.84 ± 0.98 m · s−1, respectively. The maximum value recorded by this study was 11.43 m · s−1, which was nearly identical to the back leg axe kick foot velocity (11.3 m · s−1) recorded by Sung and colleagues [10].

With the importance of the use of the rectus abdominal muscles and hip flexors to raise the kicking leg, the chest protector must be flexible and not restrict hip flexion. The kicking foot height was highest for the no chest protector condition (1.76 ± 0.05 m) followed by the novel chest protector (1.75 ± 0.05 m) then the existing chest protector (1.72 ± 0.05 m), which implied that the existing chest protector interfered with the hip flexion during the kick. There was a significant difference in the foot height between the no chest protector group and the existing chest protector group. However, there was no significant difference between the no chest protector group and the novel chest protector group.

The same order was shown for both the in-to-out axe kick and the out-to-in axe kick. With the extra height the player had the opportunity to develop more downward foot speed. The results showed significant differences between the no chest gear condition and the existing chest protector condition. The results also showed no significant differences between the no chest protector condition and the novel chest protector. Tsai and his colleagues examined how the upper arm motion affects the lower limb motion while performing the spinning heel kick [12]. Their data illustrated that the larger range of motion in the upper limbs, mainly the upper arm, then the larger the range of motion in the lower limbs. In this study, ipsilateral shoulder range of motion was calculated to observe whether the chest protector had any effect on the movement of the upper arm. Similarly, ipsilateral shoulder extension pulling speed was calculated for the same purpose. Our data suggest that even though the range of motion is larger for the upper arm movement, there were no significant differences between the groups in pulling arm speed. One of the limitations of this study is that the safety performance of the chest protector was not tested. The authors intend to test the shock absorption of the chest protector in a future study. It is also intended to develop more sizes and survey the appropriateness of fit and comfort.

CONCLUSIONS

The findings of this study, shown by the biomechanical variables, such as kick height, foot speed, hip flexion, shoulder ROM and shoulder speed, illustrate that using the novel chest protector enables a player to have more natural axe kicking motion.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aggeloussis N, Gourgoulis V, Sertsou M, Giannakou E, Mavromatis G. Repeatability of electromyographic waveforms during the Naeryo Chagi in taekwondo. J. Sport Sci. Med. 2007;6:6–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chi E.H, Song J, Corbin G. Killer App of wearable computing: wireless force sensing body protectors for martial arts; Paper presented at: UIST, 04: Proceedings of the 17th annual ACM symposium on User interface software and technology; New York, USA: ACM; 2004. pp. 277–285. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Del Vecchio F.B, Franchini E, Del Vecchio A.H.M, Pieter W. Energy absorbed by electronic body protectors from kicks in a taekwondo competition. Biol. Sport. 2011;28:75–78. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta S. The attenuation of strike acceleration with the used of safety equipment in tae kwon do. Asian J. Sport Med. 2011;2:235–240. doi: 10.5812/asjsm.34743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hansson O, O'Sullivan D. A study on the effects of rule changes on defensive and offensive behaviors from the 2001 to 2009 Taekwondo World Championship Final Matches; Paper presented at: The 3rd International Symposium for Taekwondo Studies; Korea: Gyeongju; 2011. Apr 29-30, [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koh J.O, Cassidy J.D. Incidence study of head blows and concussions in competition taekwondo. Clin. J. Sport Med. 2004;14:72–79. doi: 10.1097/00042752-200403000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koh J.O, Watkinson E.J. Video analysis of blows to the head and face at the 1999 World Taekwondo Championships. J. Sport Med. Phys. Fitness. 2002;42:348–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kukkiwon World Taekwondo Headquaters. http://www.kukkiwon.or.kr/eng/index.action. Accessed January 10, 2012.

- 9.Serina E.R, Lieu D.K. Thoracic injury potential of basic competition taekwondo kicks. J. Biomech. 1991;24:951–960. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(91)90173-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sung N.J, Lee S.Gg, Park H.J, Joo S.K. An analysis of the dynamics of the basic taekwondo kicks. US Taekwondo J. 1987;6:10–15. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsai Y.J, Gu G.H, Lee C.J, Huang C.F, Tsai C.L. Biomechanical analysis of the taekwondo front-leg axe kick; 2005. Aug 22-27, Paper presented at: The 23rd International Symposium on Biomechanics in Sport. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsai Y.J, Huang G.H. The kinematic analysis of spin-whip kick of taekwondo in elite athletes. J. Biomech. 2007:S645. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9290(07)70603-6. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsai Y.J, Hung C. The kinetic analysis of the taekwondo axe kick. Paper presented at: The 18th International Symposium on Biomechanics in Sports. 2000. Jun 25-30, http://w4.ub.uni-konstanz.de/cpa/article/view/2389/2242 accessed on February 12, 2012.

- 14.World Taekwondo Federation About WTF – Introduction. http://www.wtf.org/wtf_eng/site/about_wtf/intro.html accessed on February 12, 2012.

- 15.World Taekwondo Federation Competition rules & Interpretation. http://www.wtf.org/wtf_eng/site/rules/competition.html.

- 16.Yi K.H, Lee H.S. A suggestion of sizing system for developing taekwondo protectors. J. Kor. Soc. Cloth Text. 2008;32:1397–1406. [Google Scholar]