Abstract

Introduction

Prolonged exercise may compromise immunity through a reduction of salivary antimicrobial proteins (AMPs). Salivary IgA (IgA) has been extensively studied, but little is known about the effect of acute, prolonged exercise on AMPs including lysozyme (Lys) and lactoferrin (Lac).

Objective

To determine the effect of a 50-km trail race on salivary cortisol (Cort), IgA, Lys, and Lac.

Methods

14 subjects: (6 females, 8 males) completed a 50km ultramarathon. Saliva was collected pre, immediately after (post) and 1.5 hrs post race (+1.5).

Results

Lac concentration was higher at +1.5 hrs post race compared to post exercise (p < 0.05). Lys was unaffected by the race (p > 0.05). IgA concentration, secretion rate, and IgA/Osm were lower +1.5 hrs post compared to pre race (p < 0.05). Cort concentration was higher at post compared to +1.5 (p < 0.05), but was unaltered from pre race levels. Subjects finished in 7.81±1.2 hrs. Saliva flow rate did not differ between time points. Saliva Osm increased at post (p < 0.05) compared to pre race.

Conclusions

The intensity could have been too low to alter Lys and Lac secretion rates and thus, may not be as sensitive as IgA to changes in response to prolonged running. Results expand our understanding of the mucosal immune system and may have implications for predicting illness after prolonged running.

Keywords: lysozyme, lactoferrin, IgA, Upper Respiratory Tract Infection

INTRODUCTION

Prolonged exercise may compromise immune function [23]. The risk of infection increases 100-500% following an ultramarathon [14] as runners experience significant immune system stress post race [20]. Within two weeks after completing an ultramarathon, 25% of race finishers reported an upper respiratory symptoms (URS), and this was correlated with a decline in salivary IgA (IgA) secretion rate [20].

IgA is the most abundant antibody at the mucosal surface and is a commonly researched biomarker for innate mucosal immunity during exercise. Despite IgA's abundance, the decline in IgA after an ultramarathon may not be related to post race URS incidence [24]. Therefore it is important to continue to examine other immune factors in mucosal secretions, such as antimicrobial proteins (AMPs), which may be altered by ultra-endurance exercise.

Lysozyme (Lys) and lactoferrin (Lac) are the two most abundant AMPs. Salivary Lys and Lac are produced by epithelial cells and salivary glands, and also localized in granules of neutrophils [10]. Lys may enhance protection against gram-positive bacteria [19]. Lac may improve immunity by inhibiting iron uptake by microorganisms, thereby reducing bacterial growth [28]. Lys and Lac are also thought to function synergistically to augment immunity [8]. Lac can enhance Lys ability to remove gram–positive bacteria [19].

To date, few studies have examined the effect of acute exercise on salivary Lys and/or Lac. Lys concentration and secretion rate increased immediately after short, intense cycling [1] and Lac and Lys concentration increased after intense rowing [29]. Swimmers, however, decreased Lys concentration and secretion rate immediately after an intense workout [18], and a single session of sprinting increased the concentration of IgA and Lys, along with the secretion rate of IgA, but Lys secretion rate was unaltered immediately post or 30 min post exercise [7]. Moderate, sustained cycling for 2 h reduced salivary Lys concentration and secretion rate immediately post exercise and returned to baseline within 1 h post exercise [9]. Taken together, previous reports suggest that Lys and Lac expression can be altered by exercise, but this may be independently affected by duration and intensity.

Cortisol (Cort) is considered a reliable marker of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activity and has been shown to alter mucosal immunity through a reduction in salivary IgA [17] and ly sozyme [22]. Cort expression in response to exercise is dependent on the intensity of exercise with greater intensity leading to increased Cort release [26]. However, salivary Cort may not impact mucosal immunity in an exercise model [1]. Little is known about the relationship between Cort and AMPs during prolonged exercise.

Although past research indicates the importance of Lac and Lys for immune function, and both appear to be altered by exercise, little is known about the effects of acute, prolonged exercise. Even less is known about their response to ultra-endurance exercise in a field setting. Therefore, our purpose was to determine the effect of a trail ultramarathon race on salivary Cort, IgA, Lac, and Lys

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fourteen (6 females and 8 males) participants completed the 50 km Jemez Mountain Trail run near Los Alamos, NM (elevation: 2,231m). All subjects were experienced endurance athletes. Mean finishing time was 7.8 ± 1.2 hours (6.5 ± 1.1 km · h-1). Ambient temp was 18.8 °C at 0600, 21.1 °C at 1200, and 26.1 °C at 1700. The course consisted of 4,000 m of elevation change. The University of New Mexico's Institutional Review Board, which is in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, approved this protocol and the subjects provided informed, written consent prior to participation.

Preliminary testing

Five weeks prior to the race, subjects reported to the laboratory for preliminary screening. Body composition and cardiorespiratory fitness were assessed for all subjects. Three site skinfold (Lange, Beta Technology, Santa Cruz, CA) measurements (Men: chest, abdomen, thigh; Women: triceps, suprailiac, thigh) were used to determine percent body fat. Each site was measured in triplicate and the mean value was used to calculate percent body fat [3]. Cardiorespiratory fitness was assessed as described elsewhere [11]. Briefly, subjects walked for 8 min, 4 min at 2.5 mph and 0% grade, followed by 4 min at 4.5 mph and 5% grade. Heart rate during the second 4 min stage was used to predict VO2peak. Descriptive characteristics of subjects are displayed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

SUBJECT CHARACTERISTICS (MEAN ± SD)

| Age (yrs) | Height (cm) | Weight (kg) | Body Fat (%) | VO2peak (ml ·kg-1 min-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 43.7 ± 9.9 | 173.5 ± 9.7 | 66.3 ± 13.1 | 18.7 ± 6.6 | 47.1 ± 4.8 |

Experimental design

Saliva was collected at 3 time points: pre race (pre), immediately post race (post), and 1.5 h post race (+1.5) as previously modeled [21]. For the pre sample, subjects reported to the starting line 30 min prior to the start of the race. All subjects had eaten breakfast prior to saliva collection as they were encouraged to consume their normal pre-race meal. Post race collection occurred within 10 min of completing the race. All subjects consumed food provided by he organization within 30 min post race, thus, the 1.5 h post race sample was collected within the same amount of time post feeding between subjects. Subjects were asked to refrain from alcohol after the race. Hydration status was controlled through salivary osmolality and flow rate [27]. Subjects that did not increase saliva flow rate and/or decrease osmolality from post to 1.5 h post race, suggesting adequate rehydration, were not included in the analysis.

Saliva collection

Subjects rinsed their mouth with water 10 min prior to each collection and were not allowed to eat or drink until after the collection. Subjects were seated and asked to swallow to cleanse their mouth prior to un-stimulated collection for 4 min via passive drool into pre-weighed tubes. Subjects sat with their head tilted forward and were asked to maintain minimal oro-facial movement during collection. Saliva was immediately stored in a portable freezer after collection before being taken to the lab after the last saliva collection time. Saliva volumes were estimated by weighing to the nearest mg. Density of saliva was assumed to be 1.00 g · ml-1. Flow rate was calculated as the volume of saliva collected divided by the collection time. Secretion rate was calculated as the product of the flow rate and concentration of salivary protein.

Saliva analysis

After thawing, saliva was mixed and osmolality was assessed using a freeze point depression osmometer (Advanced Instruments, Norwood, MA, USA) after calibration with 290 mOsm/kg NaCl solution. Saliva was then analyzed using ELISA according to manufacturer's instruction. Lys and Lac (AssayPro, St. Charles, MO, USA) was detectable at 0.1 ng · ml-1 with an intra-assay coefficient of 4.1% and an inter-assay coefficient of 7.2%. IgA (Salimetrics, State College, PA, USA) was detectible at 2.5 µg · ml-1 with an intra-assay coefficient of 4.49% and an inter-assay coefficient of 8.65%. Data were generated using Gen5 software (BioTek Instruments, Inc, Winooski, VT, USA).

Statistical analysis

Data in text and tables are represented as mean ± SD. For clarity, data in figures are shown as mean ± SEM. A 1 way repeated measures ANOVA (time), using Statistica version 8 (Tulsa, OK, USA), was used to determine the effect of the race on the dependent variables. When appropriate, Tukey HSD post hoc tests were used. Pearson's Product Moment Correlation was used to determine an association between Cort, IgA, Lys, and Lac. Statistical significance was set at α ≤ 0.05. Normality and homogeneity of variance was assessed for each variable prior to statistical analysis. Data representing immunological variables of saliva were log transformed before the statistical analysis took place to correct for violations of normality.

The necessary n size was estimated to be 12 subjects, given a power of 0.80 and an alpha level of 0.05, using Statistica. Because Lac and Lys have not been assessed during ultra-endurance exercise, we based this estimate from the longest duration that has been published for either Lac or Lys [9].

RESULTS

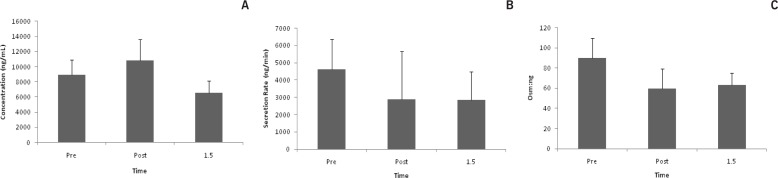

Lactoferrin

Lac concentration increased after exercise (p = 0.01). Post hoc test revealed a difference between post and +1.5 (p = 0.01). (Fig. 1a). At +1.5, Lac secretion rate decreased by 36% from pre race values, but was not statistically different (Fig. 1b). Lac/Osm was not affected by exercise (Fig. 1c).

FIG. 1A.

LAC CONCENTRATION *p < 0.05 between post and +1.5

FIG. 1B. LAC SECRETION

FIG. 1C. LAC OSM:NG

Note: Saliva was collected pre, post, and 1.5 hrs post 50 km trail race. Data are represented as mean±SEM

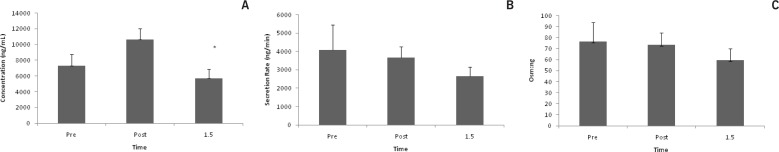

Lysozyme

Lys concentration did not change in response to the race (Fig. 2a). At +1.5, Lys secretion rate decreased by 37% from pre race values, but was not statistically different (Fig. 2b). Lys/Osm ratio was not affected by the race (Fig. 2c).

FIG. 2A.

LYS CONCENTRATION

FIG. 2B. LYS SECRETION RATE

FIG. 2C. LYS OSM:NG

Note: Saliva was collected pre, post, and 1.5 hrs post 50 km trail race. Data are represented as mean±SEM.

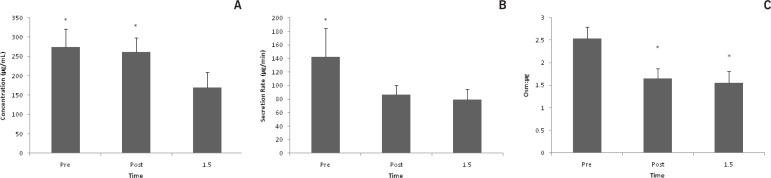

IgA

IgA concentration decreased after exercise (p < 0.001). Post hoc tests revealed a significant difference from pre to +1.5 (p < 0.001) and post to +1.5 (p < 0.001) (Fig. 3a). Secretion rate decreased with exercise (p = 0.04). Post hoc tests revealed a significant difference from pre to +1.5 (p = 0.03). (Fig. 3b). IgA/Osm decreased after exercise (p = < 0.001). Post hoc tests revealed a significant difference from pre to post (p = < 0.001), and pre to +1.5 (p = < 0.001) (Fig. 3c).

FIG. 3A.

IGA CONCENTRATION *p < 0.05 different from 1.5

FIG. 3B. IGA SECRETION RATE *P < 0.05 BETWEEN PRE AND 1.5 TIME POINTS

FIG. 3C. IGA OSM:μG. * P < 0.05 BETWEEN PRE AND POST, AND PRE AND 1.5 TIME POINTS

Note: Saliva was collected pre, post, and 1.5 hrs post 50 km trail race. Data are represented as mean±SEM.

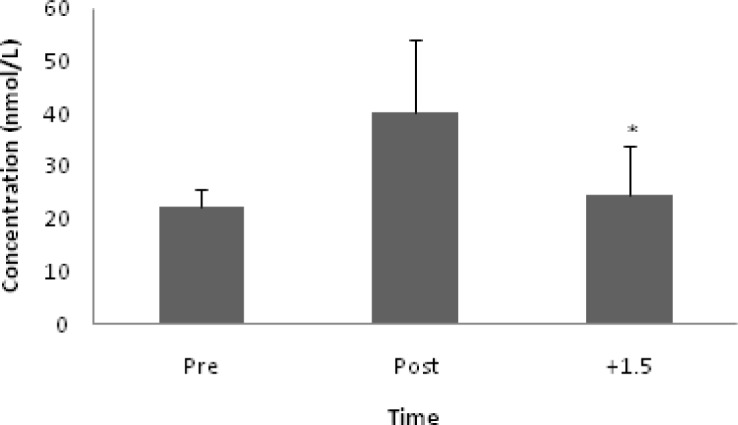

Cortisol

Cort concentration increased after exercise (p = 0.02). Post hoc test revealed a significant difference from post to +1.5 (p = 0.02; Fig. 4). Saliva Analysis. Running did not alter saliva flow rate. Saliva Osm (mOsm/kg) increased after exercise (p < 0.001), with significant differences being shown between pre and post (p = 0.01) and post and +1.5 (p < 0.001) (Table 2).

FIG. 4.

CORT CONCENTRATION. Note: *p < 0.05 between post to +1.5.

TABLE 2.

SALIVARY ANALYSIS

| Pre | Post | +1.5 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Osm (mOsm · kg-1) | Flow Rate (ml · min-1) | Osm (mOsm · kg-1) | Flow Rate (ml · min-1) | Osm (mOsm · kg-1) | Flow Rate (ml · min-1) |

| 103.2±34.6* | 0.51±0.3 | 161.6±82.5 | 0.40±0.2 | 102.3±45.7* | 0.54±0.3 |

Note: the values are: mean±SD * different from Osm post race values (p < 0.05)

Correlation

IgA and Lac concentrations (r = 0.36, p = 0.01), IgA and Lys concentrations (r = 0.37, p = 0.01), IgA and Lac secretion rates (r = 0.74, p < 0.001), IgA and Lys secretion rates (r = 0.77, p < 0.001), and Lac and Lys secretion rates (r = 0.65, p < 0.001) were all correlated. There was no association between Lac and Lys concentrations, Cort and IgA concentration, Cort and Lys concentration, Cort and Lac concentration, IgA Osm/µg and Lac Osm/ng, IgA Osm/µg and Lys Osm/ng, Lac Osm/ng and Lys Osm/ng.

DISCUSSION

The main finding of this study was that Lys and Lac secretion rates were unaffected by the race. The ultramarathon caused a decline in the secretion rate and Osm/µg of IgA. Also, Lac and Lys secretion rates were correlated. These results occurred without an alteration in flow rate. Taken together, these data suggest increased sensitivity to prolonged running in IgA compared to Lys and Lac.

While the IgA response to prolonged running has been extensively examine [20, 21, 23, 24], to our knowledge, this is the first report detailing the effect of prolonged exercise (>3 h) on Lys and/or Lac. The importance of IgA quantification after an ultramarathon is it's inverse relationship with URS [20], though some have questioned this [24]. It is suggested that reductions in IgA cannot be solely responsible for the decline in immune function that may lead to URS. Therefore, it is important to describe changes in other prominent mucosal factors.

2 h of moderate intensity cycling depressed Lys concentration and secretion rate compared to pre exercise values [9], while short, intense bouts of exercise increase Lys immediately post exercise [1, 13, 29]. Indeed, the intensity of exercise appears to contribute to Lys secretion rate as high intensity exercise demonstrated an increase in Lys secretion while there was no change at a submaximal intensity [1]. Limited data exists regarding salivary Lys, but is postulated that the ability of mononuclear cells to secrete Lys during the post exercise period may be decreased due to a “refractory period”. During this time, the secretion of Lys is inhibited until “recovery and restoration is achieved [30].” This may be similar for epithelial cells and could be a plausible explanation for the decreased Lys secretion rate after 2 hours of cycling. Our data showed no alteration in Lys from pre race values and this is likely due to the low intensity our subjects used to complete the ultramarathon. Indeed, laboratory studies suggest that experienced endurance athletes can maintain ∼65% of their VO2peak during 4 h of running [6], which is below the threshold necessary to increase Lys secretion rate [1] and similar to the exercise intensity necessary to decrease Lys secretion rate [9]. The current subjects, however, ran on average 3 h longer than Davies [6] subjects, so we can assume the exercise intensity in the current study was less than 65%, which could be too low significantly alter Lys secretion rate.

Limited data exists regarding salivary Lac and acute exercise, but Lac concentration may increase after short, intense exercise [29]. However, Lac is also found in specific granules of neutrophils. Serum Lac concentration increased immediately after a marathon [25]. Our data supports previous work [25] that showed an increase in Lac concentration after prolonged running. However, data from the current study may represent an increase in osmolality and not an increase in the availability of Lac on the mucosal surfaces since the secretion rate and Osm/µg were unaltered. Thus, it appears that salivary Lac may not be substantially altered through prolonged running.

Lac and Lys have been shown to act synergistically to defend against bacterial invasion [8], and our correlative data suggests that this finding may extend to ultramarathons. Although salivary measurements of Lac and Lys were not affected by the race, secretion rates were correlated. Lac may enhance Lys’ ability to remove gram– positive bacteria by making the mucosal environment unsuitable for colonies of bacteria to grow and this could be an important variable with regards to post race URS.

As the most abundant AMP at the mucosal surface, IgA is the primary means of measuring the “first line of defense” at the mucosal surface. Deficiencies in IgA concentration [16] and low flow rates [12] may result in increased rates of infection. While the current study did not assess post race URS due to limited sample size, the post race ultramarathon salivary IgA data is similar to previously published work [21, 24]. With regards to data from the current study, IgA seems to be more sensitive to ultramarathons than Lys or Lac.

Cort concentration was not correlated with mucosal immunity measures and thus, the HPA axis may not be regulating mucosal immunity at 1.5 h post race. This has been previously shown in laboratory work for IgA and Lys [1, 2] and our data extends this finding to an ultramarathon. However, our last time point could have been too short to assess Cort's effect on mucosal immunity. The post exercise (2-24 h) fall in IgA may be related to Cort [15], especially since there is often a delay in the appearance of Cort in the circulation [26].

Flow rate did not change from pre race values. The exercise intensity in the current study may have been too low to increase sympathetic nervous system activity above a critical threshold to reduce salivary flow rate. In addition, hydration can affect osmolality flow rate. Walsh, et al [27] noted that a significant reduction in flow rate only occurred after a 2% decrease in body weight, while osmolality increased after 1.1% body mass loss. In the current study osmolality increased immediately post exercise before returning to pre race levels 1.5 h post race, while flow rate did not change. Accordingly, we can assume that our subjects were 1.1-2.0% dehydrated. Taken together, our data suggest that the intensity of exercise was low, and adequate hydration was maintained, therefore flow rate was unaltered.

Limitations

This observational field study provides unique “real world” insights into the role of mucosal immunity. However, current results should be corroborated through a more stringent experimental design that accounts for caloric intake and controls for hydration. Although all subjects consumed food pre and post race, and ingested fluids during the race, specific macronutrient and fluid intake was not recorded. However, Carbohydrate (CHO) consumption during a marathon [21], or immediately after 2 h of cycling at 75% VO2max [4], did not affect IgA concentration or secretion rate compared to the control group. In addition, saliva flow rate, IgA concentration, and IgA secretion rate after 2 h of cycling did not differ in subjects who were fed prior to exercise compared to those who cycled after an overnight fast [2]. Lys secretion rate was similar in the first hour of recovery after the ingestion of a CHO-protein drink consumed post exercise compared to the fasted group [4]. Supplementation with bovine colostrums attenuated the post exercise decrements in Lys concentration and secretion rate [9] and increased resting IgA levels [5]. The effect of macronutrient or micronutrient consumption pre or post exercise on Lac is unclear. Taken together, macronutrient intake before or after endurance exercise (>2 h) has little impact IgA and Lys secretion rates. Thus, despite limited nutritional control, the current observational field study extends the findings of laboratory studies to a real world setting.

CONCLUSIONS

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine Lys and Lac after an ultramarathon. Furthermore, assessing Lys and Lac after acute, prolonged exercise in a field setting is novel and provides direct application for sport scientists. Our data suggests that IgA is more sensitive to prolonged running than either Lys or Lac. Results from the current study expand our understanding of the mucosal immune system and may have implications for predicting URS after prolonged running.

Authors’ declaration

There are no conflicts of interest for any author.

There were no funding sources for this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allgrove J, Gomes E, Hough J, Gleeson M. Effects of exercise intensity on salivary antimicrobial proteins and markers of stress in active men. J. Sports Sci. 2008;26:653–661. doi: 10.1080/02640410701716790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allgrove J.E, Geneen L, Latif S, Gleeson M. Influence of fed or fasted state on the s-IgA response to prolonged cycling in active men and women. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2009;19:209–221. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.19.3.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brozek J, Grande F, Anderson J.T, Keys A. Densitometric analysis of body composition: Revision of some quantitative assumptions. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1963;110:113–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1963.tb17079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costa R.J, Fortes M.B, Richardson K, Bilzon J.L, Walsh N.P. The effects of postexercise feeding on saliva antimicrobial proteins. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2012;22:184–191. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.22.3.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crooks C.V, Wall C.R, Cross M.L. The effect of bovine colostrum supplementation on salivary IgA in distance runners. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2006;16:47–64. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.16.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davies C, Thompson M. Physiological responses to prolonged exercise in ultramarathon athletes. J. Appl. Physiol. 1986;61:611–617. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1986.61.2.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davison G. Innate immune responses to a single session of sprint interval training. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2011;36:395–404. doi: 10.1139/h11-033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davison G, Allgrove J, Gleeson M. Salivary antimicrobial peptides (LL-37 and alpha-defensins HNP1-3), antimicrobial and IgA responses to prolonged exercise. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2009;106:277–284. doi: 10.1007/s00421-009-1020-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davison G, Diment B.C. Bovine colostrum supplementation attenuates the decrease of salivary lysozyme and enhances the recovery of neutrophil function after prolonged exercise. Br. J. Sport Nutr. 2010;103:1425–1432. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509993503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dubin R, Robinson S, Widdicombe J. Secretion of lactoferrin and lysozyme by cultures of human airway epithelium. Am. J. Physiol. 2004;286:L750–L755. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00326.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ebbelin C.B. Development of a single stage submaximal treadmill walking test. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1991;23:966–972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fox P.C, van der Ven P.F, Sonies B.C, Weiffenbach J.M, Baum B.J. Xerostomia: evaulation of a symptom with increasing significance. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1975;110:519–525. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1985.0384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Francis J.L, Gleeson M, Pyne D.B, Callilster R, Clancy R. Variation of salivary immunoglobulins in exercising and sedentary populations. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2005;37:571–578. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000158191.08331.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gleeson M. Immune function in sport and exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 2007;103:693–699. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00008.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gleeson M, Bishop N.C, Steren V.L, Hawkins A.J. Diurnal variation in saliva immunoglobulin A concentration and the effecet of a previous day of heavy exercise. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2001;33(Suppl.) Abstract 54. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanson L.A, Bjorkander J, Oxelius V. Selective IgA Deficiency. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1983. Primary and secondary immunodeficiency disorders; pp. 62–64. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huckelbridge L.A, Clow A, Evans P. The relationship between salivary secretory immunoglobulin A and cortisol: neuroendocrine response to awakening and the dirurnal cycle. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 1998;31:69–76. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8760(98)00042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koutedakis Y, Sabin E, Perera S. Modulation of salivary lysosyme by training in elite male swimmers. J. Sports Sci. 1996;14:90. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leitch E.C, Willcox M.D. Elucidation of the antistaphylococcal action of lactoferrin and lysozyme. J. Med. Microbiol. 1999;48:867–871. doi: 10.1099/00222615-48-9-867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nieman D.C. Immune function responses to ultramarathon race competition. Med. Sport. 2009;13:189–196. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nieman D.C, Henson D.A, Fagoaga O.R, Utter A.C, Vinci D.M, Davis J.M, et al. Change in salivary IgA following a competitive marathon race. Int. J. Sports Med. 2002;23:69–75. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-19375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perera S, Uddin M, Hayes J. Salivary lysozyme: A non-invasive marker for the study of the effects of stress on natural immunity. Int. J. Behav. Med. 1997;4:170–178. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0402_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peters E.M, Bateman E.D. Ultramarathon running and upper respiratory tract infections. South Afr. Med. J. 1983;64:582–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peters E.M, Shaik J, Kleinveldt N. Upper respiratory tract infection symptoms in ultramarathon runners not related to immunoglobulin status. Clin. J. Sport Med. 2010;20:39–46. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e3181cb4086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suzuki K, Nakaji S, Yamada M. Impact of a competitive marathon race on systemic cytokine and neutrophil responses. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003;35:348–355. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000048861.57899.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Viru A, Viru M. Cortisol - an essential adaptaion hormone in exercise. Int. J. Sports Med. 2004;25:461–464. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-821068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walsh N.P, Montague J.C, Callow N, Rowlands A.V. Saliva flow rate, total protein concentration and osmolality as potential markers of whole body hydration status during progressive acute dehydration in humans. Arch. Oral Biol. 2004;49:149–154. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weinberg E.D. Iron depletion: a defense against intracellular infection and neoplasia. Life Sci. 1992:1289–1297. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(92)90279-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.West N.P, Pyne D.B, Kyd J.M, Renshaw G.M, Fricker P.A, Cripps A.W. The effect of exercise on innate mucosal immunity. Br. J. Sports Med. 2010;44:227–231. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.046532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.West N.P, Pyne D.B, Renshaw G, Cripps A.W. Antimicrobial peptides and proteins, exercise and innate mucosal immunity. FEMS Immunol. Med Mircobiol. 2006;48:293–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2006.00132.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]