Abstract

In gymnastics every exercise finishes with a landing. The quality of landing depends on subjective (e.g. biomechanical) and objective (e.g. mechanical characteristics of landing area) factors. The aim of our research was to determine which biomechanical (temporal, kinematic and dynamic) characteristics of landing best predict the quality of landing. Twelve male gymnasts performed a stretched forward and backward salto; also with 1/2, 1/1 and 3/2 turns. Stepwise multiple regression extracted five predictors which explained 51.5% of landing quality variance. All predictors were defining asymmetries between legs (velocities, angles). To avoid asymmetric landings, gymnasts need to develop enough height; they need higher angular momentum around the transverse and longitudinal axis and they need to better control angular velocity in the longitudinal axis.

Keywords: gymnastics, biomechanics, errors

INTRODUCTION

Every exercise in artistic gymnastics (whether men's or women's gymnastics) ends with a landing. Research results show a rather low rate of success of landings in competitions [14, 16, 18]. At the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta [16] landings from the high bar and parallel bars were investigated. Competitors performed twenty landings. Only one was performed without a mistake. Eight were over- and eleven under-rotated. Landing is characterized by high landing vertical forces with the double salto backward tucked vertical landing force from 8.8 up to 14.4 multiples of bodyweight [20]; vertical landing forces from different heights (0.32 m, 0.72 m, 1.28 m) were between 3.9 and 11 multiples of bodyweight [15]; in acrobatic jumps [10] 13.9 multiples of bodyweight vertical landing force were reported. Axis of rotation (only transverse, combined transverse and longitudinal axis), number of turns around the longitudinal axis (more turns mean more mistakes) and initial landing height have a significant impact on the magnitude of the landing mistake, while the direction of salto has no relation to the magnitude of the landing mistake [14]. Average angular velocities (ω) for different saltos backward are: around the longitudinal axis ω=947 degrees · s-1 and around the transverse axis ω=853 degrees · s-1 [4]. Successful landing is performed with high body stiffness in the first part of landing (from the first contact to the maximum force) [19]. The stiffness is mostly changed with ankle and knee angle, which is in accordance with maximum external forces and angular accelerations of trunk, thigh and calf [7]. Only active change of knee and ankle angle lowers external forces [9, 26]. According to the maximum knee angle, stiff landing (angle greater than 63 degrees) and soft landing (angle less than 63 degrees) can be differentiated [5]. Appropriate limb angles at the moment of touch down raise muscles’ ability to absorb energy [21]. The rank order of muscle activity is the same for jumps from different heights [1]. Asymmetric landing leg load was found in volleyball blocking [17]. At high level competitions the quality of landing often determines the final rankings. According to the quality of landing it can be defined as perfect (stick one), with small error, medium error, large error or fall. In the FIG (Fédération Internationale de Gymnastique) 2009 Code of Points (COP) for Men [8] the following landing errors are defined: small ones with deduction (legs apart on landing up to shoulder width, unsteadiness, minor adjustments of feet, or excessive arm swings on landing, loss of balance (small step or hop), incomplete twist (up to 30 degrees)), medium ones (legs apart on landing more than shoulder width, loss of balance (large step or hop or touching the mat with one or two hands), incomplete twist (31-60 degrees)), large errors (loss of balance (support with one or two hands on mat), incomplete twist (61-90 degrees)) and fall (during landing, or landing without feet contacting mat first). Reliability and validity of FIG's principles of evaluation are very high [12, 13]. Researchers have found many factors that affect the landings, but no studies have been done in vivo in which the quality of landing is related to biomechanical characteristics and how lateral symmetry affects the quality of landing. The aim of our research was to investigate how temporal, kinematic and dynamic characteristics of landing are related to the landing quality.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Twelve gymnasts from the Slovenian national gymnastics team took part in the study. On the day of the measurements the average age was 18.75 ± 2.63 years, average height was 168.85 ± 6.41 cm and average weight was 67.48 ± 10.16 kg. Every gymnast had to demonstrate proficiency in performing the acrobatic skills of interest.

Procedure

Each gymnast performed the following saltos once: stretched forward and backward salto, stretched forward and backward salto with 1/2 twist, stretched forward and backward salto with 1/1 twist, stretched forward and backward salto with 3/2 twists (one gymnast did not perform the salto forward stretched with 3/2 twists due to safety reasons). The number of turns around the longitudinal axis in combination with salto direction (forward and backward) leads to similar landings, e.g. salto forward has the same landing as salto backward with ½ twist.

All the saltos were performed on the Spieth competition floor after a warm up. Informed consent was obtained from each gymnast according to the Declaration of Helsinki and approval of the ethic commission of the Faculty of Sport, University of Ljubljana. The difficulty of the salto was increased in half twist intervals. Because the gymnasts did not twist in the same direction, the leading and non-leading limb was defined according to the direction of the twist. The limb corresponding to the direction of the gymnast's twist was assigned as the leading limb. In that sense the gymnast who twisted to the left had his left leg as his leading leg and his right leg as his non-leading leg.

Data acquisition and data analysis

The Parotec system was used to measure temporal and dynamic characteristics at the moment of landing. Parotec insoles are equipped with 24 discrete hydrocell pressure sensors for each foot. Both insoles are triggered at the same time. Hydrocell technology enables one to measure compressive force and shear force but does not discriminate between them. The sensors have shown less than 2% measurement error in the range of 0–400 kPa and reliably provided highly consistent and valid data [3, 27] which were deemed acceptable for our study. The following temporal variables were measured and calculated: contact time (time from first contact with feet on floor to time when ground reaction forces are the same as the gymnast's body weight), difference between leading and non-leading leg in contact time, time needed to reach maximum ground reaction forces, time from maximum ground reaction forces to body weight, time to the first peak of ground reaction forces, time to the second peak of ground reaction forces, time to maximum ground reaction forces of leading leg, time to maximum ground reaction forces of non-leading leg, time to maximum difference between left and right leg ground reaction forces. The following dynamic variables were measured and calculated: average ground reaction forces of both legs in contact time, average ground reaction forces of leading leg, average ground reaction forces of non-leading leg, proportion between average ground reaction forces of leading and non-leading leg, impact force of both legs in contact time, impact of leading leg in contact time, impact of non-leading leg in contact time, normalized impact (impact/ maximum impact per subject per salto variation) in contact time, normalized impact of leading leg (impact/maximum impact per subject in any salto) in contact time, normalized impact of non-leading leg (impact/maximum impact per subject in any salto) in contact time, maximum ground reaction forces, the first peak of ground reaction forces, the second peak of ground reaction forces, maximum difference between ground reaction forces of leading and non-leading leg in contact time, average ground reaction forces of leading leg in contact time, average ground reaction forces of non-leading leg in contact time, proportion between average ground reaction forces between leading and non-leading leg, maximum ground reaction forces of leading leg, maximum ground reaction forces of non-leading leg.

The Ariel Performance Analysis System was used to measure kinematic characteristics of landing. All saltos were recorded with three video cameras with the frequency of 50 frames per second. The landing area was defined as the total size of 3x2x1 metres. The sample of independent variables is represented by a group of kinematic variables which were calculated from a 7-segment model of the gymnast. The following segments were used: right/left foot, right/left shank, right/left thigh and the segment that connects the left and right hip. With the help of the 7-segment model we were able to calculate the following kinematic variables: vertical leading and non-leading hip velocity, angle in leading and non-leading ankle, angle in leading and non-leading knee, distance between left and right knee, distance between left and right foot, angle change in contact time in knee and ankle (leading and non-leading leg).

The landing quality was determined according to the FIG COP by two qualified international level 2 judges. The sum of deductions represented the final score for quality of landing. Deductions were: small step or hop (0.1 point), long step or hop (0.3 point), touching floor with hands (0.3 point), hands support on floor (0.5 point), fall (1.0 point). The reliability and validity of FIG's principles of judging in gymnastics are very high [2, 12, 13].

The main focus of the study is on the influence of the symmetry/asymmetry on the landing quality. Therefore temporal, kinematic and dynamic variables that could expose the symmetry/asymmetry were used. For the purpose of regression analysis only non-composite variables were subjected to further analysis.

As we wanted to find the most important predictors of landing quality we used SPSS 18.0 and performed linear stepwise regression analysis with 46 variables as predictors. The statistical significance level for regression and predictors was set to p<0.05.

RESULTS

In Table 1 descriptive statistics are shown only for those variables which have significant prediction of landing quality.

TABLE 1.

DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS OF LANDING QUALITY AND BEST PREDICTORS

| Mean | Std. Deviation | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Landing quality | 0.30 | 0.22 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Diff. in vert. hip velocity in lowest position (m · s-1) | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.66 |

| Vert. velocity of leading hip at first contact (m · s-1) | -4.63 | 0.66 | -5.97 | -2.52 |

| Diff. in ankle angle in lowest position (degrees) | 9.22 | 12.64 | 0.00 | 77.00 |

| Diff. in knee angle at first contact (degrees) | 3.51 | 3.47 | 0.00 | 17.00 |

| Knee angle change, non-leading leg (degrees) | 55.42 | 12.72 | 3.00 | 84.00 |

TABLE 2.

REGRESSION ANALYSIS RESULTS

| Step | R (uncorrected) | R Square | F Change | df1 | df2 | Sig. F Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.503 | 0.253 | 31.487 | 1 | 93 | <0.001 |

| 2 | 0.631 | 0.398 | 22.173 | 1 | 92 | <0.001 |

| 3 | 0.679 | 0.461 | 10.676 | 1 | 91 | 0.002 |

| 4 | 0.702 | 0.493 | 5.627 | 1 | 90 | 0.020 |

| 5 | 0.718 | 0.515 | 4.127 | 1 | 89 | 0.045 |

|

| ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | |||

| B | Std. Error | Beta | ||||

|

| ||||||

| (Constant) | 0.724 | 0.142 | 5.094 | <0.001 | ||

| Diff. in vert. hips velocity in lowest position | 0.654 | 0.151 | 0.349 | 4.330 | <0.001 | |

| Vert. velocity of leading hip at first contact | 0.076 | 0.028 | 0.233 | 2.749 | 0.007 | |

| Diff. in ankle angle in lowest position | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.214 | 2.546 | 0.013 | |

| Knee angle change non leading leg | -0.004 | 0.001 | -0.219 | -2.791 | 0.006 | |

| Diff. in knee angle in first contact | 0.011 | 0.005 | 0.170 | 2.032 | 0.045 | |

DISCUSSION

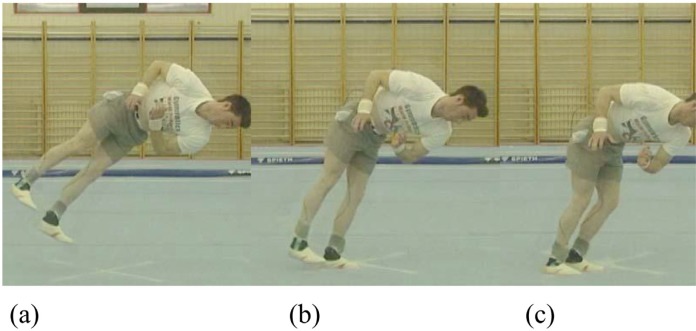

The average deduction for landing was 0.30 points, which can be described as medium error. The multiple correlation between landing quality and best predictors was 0.718, which means the five best predictors explain 51.5% of landing quality (the majority of it). The best predictors were difference in vertical hip velocity in lowest position, vertical velocity of leading hip at first contact, difference in ankle angle in lowest position, knee angle change (from first contact with floor down to lowest position) in non-leading leg and difference in knee angle at first contact. All variables were positively related to landing score (the bigger the error at landing, the greater the value of the variable) except for knee angle change in the non-leading leg, which was negatively related (the bigger the error at landing, the smaller the value of the variable). The main predictor was the difference in vertical hip velocities in the lowest position. It showed that while the leading hip stopped at the lowest position the non-leading hip was still declining (diff.= 0.1 m · s-1); it seems the uneven load on the legs (whole leg chain) was mostly expressed in the hips; it is worth noting that such a load makes the vertebra curved in an S shape like in scoliosis (seen from video recorded material). Despite the fact that the lowest position is not shown in

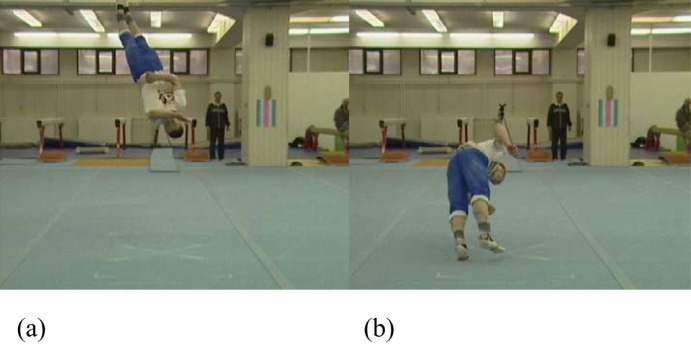

Figure 1(c) the asymmetric load on the hips can be seen, where the leading leg is in a lower position. The cause of different vertical hip velocities is the lack of angular momentum at the moment of take-off [24]. The relation between vertical velocity of the leading hip at first contact and landing quality was positive, but nature is just the opposite, as a higher velocity (as the gymnast is falling from height, the vertical velocity is negative; higher vertical hip velocity means the flight phase is shorter in duration and the maximum height of the salto is lower) means lower landing quality, which can be shown as under-rotation of the salto, which results in more deductions for the landing. Vertical velocity of the leading hip at the moment of the first contact is 4.63 m · s-1. It can be calculated from kinematics (t=v/g; h=gt2/2) that it was falling 1.09 metres. If there were more height in flight (Figure 2(a) and 2(b)) under-rotation would not be happening and better landing performance could be achieved as the strategy is stable independently of the flight height [6].

FIG. 1.

LANDING – PREPARATION (A), FIRST CONTACT (B), MOMENT OF MAXIMUM FORCE (C)

FIG. 2.

FLIGHT (A) AND MOMENT THE FIRST CONTACT WITH FLOOR (B)

The third best predictor was the difference in ankle angle between the legs in the lowest position, which is on average 9.5 degrees; this can be evaluated as quite a big difference as we were expecting mostly symmetric landings. The difference in ankle angle starts at the first contact (Figure 1(b), 2(b)) and increases until the lowest point. A bigger difference causes mostly unbalanced distribution of pressure on the feet; as one foot is more loaded it ruins the equilibrium and corrective movements are needed (step aside, hop).

The fourth best predictor is knee angle change of the non-leading leg from the first contact to the lowest position. The amortization in the non-leading knee was on average 55.4 degrees; the relation to landing quality is negative, which means if there were more angle change the landing would be better. It can be stated that the softer is the landing by Devita and Skelly [5] criteria, the better is the landing.

The last significant predictor was the difference in knee angle between the leading and non-leading leg at first contact. Although it is small in size (3.5 degrees) it shows the beginning of landing asymmetry and its importance for asymmetry development in further landing phases. The asymmetry obviously continues in most cases and develops further in worse landing quality. According to Marinšek and Čuk [14] perfect landings can be performed and they are performed at competitions; from a motor control perspective it is easier to control the landing after a better performed salto (e.g. higher duration of flight, optimum angular momentum); short times from feet to floor contact require a lot and specific training to start to predict, control and accommodate landing characteristics; as we stated, a perfect landing is possible, but unfortunately rare.

CONCLUSIONS

The main reasons for low quality landings are asymmetries between the legs; asymmetries predict more than 50% of landing quality variance. Although temporal, dynamic and kinematic variables were included in the research, only kinematic variables were significant in stepwise regression. From the practical perspective this is good, as coaches can use video cameras during training to analyse and present the reasons for bad landing quality to their gymnasts. To avoid asymmetric landing, gymnasts first of all need to develop enough height; second, they need higher angular momentum around the transverse and longitudinal axis; and third, they need to better control angular velocity in the longitudinal axis. Therefore they need to improve their motor abilities and technique.

Probably long-term asymmetric landing can cause acute (mostly like ankles or knees) or chronic injuries (most likely the back trunk) [22, 25]. It is especially important that young gymnasts learn to perform every landing as symmetrically as possible.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arampatzis A, Morey-Klapsing G, Brüggemann G.P. The effect of falling height on muscle activity and foot motion during landings. J. Electromyo. Kinesiol. 2003;13:533–544. doi: 10.1016/s1050-6411(03)00059-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bučar Pajek M, Forbes W, Pajek J, Leskošek B, Čuk I. Reliability of real time judging system. Sci. Gymn. J. 2011;3:47–54. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chesnin K.J, Selby-Silverstein L, Besser M.P. Comparison of an in-shoe pressure measurement device to a force plate: concurrent validity of center of pressure measurements. Gait Posture. 2000;12:128–133. doi: 10.1016/s0966-6362(00)00071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Čuk I, Ferkolj S. Kinematic analysis of some backward acrobatic jumps. Procedings of XVIIIth International Symposium on Biomechanics in Sports; Hong Kong. 2000. pp. 36–39. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Devita P, Skelly W.A. Effect of landing stiffness on joint kinetics and energetics in the lower extremity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1992;24:108–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dyhre-Poulsen P, Simonsen E.B, Voigt M. Dynamic control of muscle stiffness and H reflex modulation during hopping and jumping in man. J. Physiol. 1991;437:287–304. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elvin N.G, Elvin A.A, Arnoczky S.P, Torry M.R. The correlation of segment accelerations and impact forces with knee angle in jump landing. J. Appl. Biomech. 2007;23:203–212. doi: 10.1123/jab.23.3.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.FIG. Code of Points for Men Artistic Gymnastics Competitions (2009 Edition) Available at: http://figdocs.lx2.sportcentric.com/external/serve.php?document=2921. Accessed 14.10.2011.

- 9.Hargrave M.D, Carcia C.R, Gansneder B.M, Shultz S.J. Subtalar pronation does not influence impact forces or rate of loading during a single-leg landing. J. Athl. Train. 2003;38:18–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karacsony I, Čuk I. Floor exercises – Methods, Ideas, Curiosities, History. Ljubljana: STD Sangvinčki; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kleina P.J, DeHavenb J.J. Accuracy of three-dimensional linear and angular estimates obtained with the ariel performance analysis system. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1995;76:183–189. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(95)80028-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leskošek B, Čuk I, Karacsony I, Pajek J, Bučar Pajek M. Realibility and validity of judging in men's artistics gymnastics at the 2009 university games. Sci. Gymn. J. 2010;2:25–34. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leskošek B, Čuk I, Pajek J, Forbes W, Bučar Pajek M. Bias of in men's artistic gymnastics at the European Championship 2011. Biol. Sport. 2012;29:107–113. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marinšek M, Čuk I. Landing errors in the men's floor exercise are caused by flight characteristics. Biol. Sport. 2010;27:123–128. [Google Scholar]

- 15.McNitt-Gray J. Kinetics of the lower extremities during drop landings from three heights. J. Biomech. 1993;26:1037–1046. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(05)80003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McNitt-Gray J, Munkasy B.A, Costa K, Mathiyakom D, Eagle J, Ryan M.M. Invariant features o multi joint control strategies used by gymnasts during landings performed in Olympic competition. Ontario, Canada: North American Congress of Biomechanics. University of Waterloo; 1998. pp. 441–442. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McNitt-Gray J, Munkasy B.A, Mathiyakom W, Somera N.H. Asymmetrical loading of lead and lag legs during landings of blocking movements. Volleyball USA. 1998;26:14–16. [Google Scholar]

- 18.McNitt-Gray J, Requejo P, Costa K, Mathiyakom W. Landing success rate during the artistic gymnastics competition of the 2000 Olympic Games: Implications for improved gymnast/mat interaction. Retrieved June 8th, 2006, from http://coachesinfo.com/category/gymnastics/75/.

- 19.McNitt-Gray J, Takashi Y, Millward C. Landing strategies used by gymnasts on different surfaces. J. Appl. Biomech. 1994;10:237–252. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Panzer V.P. Lower Extremity Loads in Landings of Elite Gymnasts; Oregon: University of Oregon; 1987. Doctoral dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prassas S, Gianikellis K. Vaulting Mechanics. Applied Proceedings of the XXth International Symposium on Biomechanics in Sport – Gymnastics; Caceres, Spain: University of Extremadura, Department of Sport Science; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steffen T, Baramki H.G, Rubin R, Antoniou J, Aebi M. Lumbar intradiscal pressure measured in the anterior and posterolateral annular regions during asymmetrical loading. Clin. Biomech. 1998;13:495–505. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(98)00039-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson D.J, Smith B.K, Gibson J.K. Accuracy of reconstructed angular estimates obtained with the ariel performance analysis system. TM. Phys. Ther. 1997;77:1741–1746. doi: 10.1093/ptj/77.12.1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yeadon M.R. The biomechanics of twisting somersaults. Part I: Rigid body motions. J. Sports Sci. 1993;11:187–198. doi: 10.1080/02640419308729985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yeadon M.R. Learning how to twist fast. In: Sanders R.H, Gibb B.J, editors. Applied Proceedings of the XVIIth International Symposium on Biomechanics in Sports – Acrobatics. Western Australia: School of Biomedical and Sport Sciences, Edith Cowan University, Perth; 1999. pp. 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu B, Lin C.F, Garrett W.E. Lower extremity biomechanics during the landing of a stop-jump task. Clin. Biomech. 2006;21:297–305. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zequera M, Stephan S, Paul J. The „parotec” foot pressure measurement system and its calibration procedures. 28th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society; New York, NY. 2006. pp. 5212–5216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]