Abstract

The aim of this study was to simulate the activity pattern of rink hockey by designing a specific skate test (ST) to study the energy expenditure and metabolic responses to this intermittent high-intensity exercise and extrapolate the results from the test to competition. Six rink hockey players performed, in three phases, the 20-metre multi-stage shuttle roller skate test, a tournament match and the ST. Heart rate was monitored in all three phases. Blood lactate, oxygen consumption, ventilation and respiratory exchange ratio were also recorded during the ST. Peak HR was 190.7±7.2 beats · min−1. There were no differences in peak HR between the three tests. Mean HR was similar between the ST and the match (86% and 87% of HRmax, respectively). Peak and mean ventilation averaged 111.0±8.8 L · min−1 and 70.3±14.0 L · min−1 (60% of VEmax), respectively. VO2max was 56.3±8.4 mL · kg−1 · min−1, and mean oxygen consumption was 40.9±7.9 mL · kg−1 · min−1 (70% of VO2max). Maximum blood lactate concentration was 7.2±1.3 mmol · L-1. ST yielded an energy expenditure of 899.1±232.9 kJ, and energy power was 59.9±15.5 kJ · min−1. These findings suggest that the ST is suitable for estimating the physiological demands of competitive rink hockey, which places a heavy demand on the aerobic and anaerobic systems, and requires high energy consumption.

Keywords: field test, intermittent exercise, physiological responses, energy expenditure, rink hockey

INTRODUCTION

Rink hockey, also known as roller hockey or hardball hockey in the USA, is a team sport that is played on a rink of 20 x 40 metres with a wall around its perimeter. The actual time of the game is 50 minutes (two halves of 25 minutes), but the total time including pauses is approximately 70-80 minutes and sometimes more [6]. Mean participation time of field players is between 40 and 70 minutes per match [10].

The match demands of “multiple-sprint” sports include periods of physical activity and recovery interspersed with brief periods of sprinting [1, 6, 10]. In rink hockey, some studies have monitored the physiological demands in competition, showing that the heart rate is between 85 and 90% of HRmax, and blood lactate concentration is between 4.0 and 4.6 mmol · L−1[7, 19].

In other multiple-sprint sports, investigators have tried to replicate the demands by means of field and laboratory tests [4, 13, 16]. The development of portable metabolic test systems has made it possible to measure oxygen consumption (VO2) in competition, and to develop specific tests [2, 11, 12]. During specific tests, VO2 consumption has been shown to increase up to 62.2 ± 5.0 mL · kg−1 · min−1 in professional soccer players [12] and 59.1 ± 4.8 mL · kg−1 · min−1 in young, trained players [2]. In squash VO2 increased to 54 ± 4.8 mL · kg−1 · min−1[11]. When comparing a soccer-specific field test and a laboratory treadmill test, no differences were observed in VO2max, maximal heart rate, maximal breathing frequency, respiratory exchange ratio or oxygen pulse [13].

Some investigations have measured maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max) in rink hockey players by means of laboratory and field tests using maximal continuous tests, with maximal values of approximately 55 mL · kg−1 · min−1 in elite rink hockey players [18, 19]. However, even with portable systems, it is difficult to perform measurements in an actual game situation. In order to estimate the demands of the game, it is important that the field tests simulate the game conditions as accurately as possible.

Therefore, the aims of this study were: (1) to design a skate test that simulates the activity pattern characteristic of rink hockey, (2) to describe the energy expenditure and metabolic responses to this intermittent high-intensity skating test, and (3) to extrapolate the results from the test to competition.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

This study included six subjects from a rink hockey team in the Spanish first division. Their mean (SD) age was 23.4 ± 3.1 years, height 173.7 ± 4.7 m, and body mass 72.3 ± 5.1 kg. The protocol of this study was in accordance with the revised declaration of Helsinki. The Ethical Committee of Asturias University Central Hospital approved the study. All subjects gave written informed consent to participate in this study.

Experimental design

Data were collected from three separate phases at the end of the pre-season period (after four weeks of training). In phase one, all participants completed the 20-metre multi-stage shuttle roller skate test (20MSRST) [18], which was adapted to rink hockey purposes from the multi-stage fitness test (20-metre shuttle run) [14, 15]. In phase two, the six subjects participated in one tournament match, and in phase three they completed the simulation test. The three phases were conducted in the same sports hall (having a polished cement floor with good adherence for roller skates).

Experimental protocol

20-metre multistage shuttle roller skate test

The participants were required to skate between two lines, 20 m apart, with the same protocol to that described by Brewer, Ramsbottom, & Williams [9]. The subjects started skating at 8.5 km · h−1 and increased their speed by 0.5 km · h−1 each minute. Speed was dictated by an audio signal from a computer using software developed for this purpose. The software was programmed with LabWindows CVI 7.1 (National Instruments Corporation, USA). Before the test, all subjects performed the same 15 minute warm-up, which included 10 minutes of stretching and 5 minutes of skating on the test track at 7.5 km · h−1. All subjects were verbally encouraged to perform maximally during the test. The protocol consisted of skating from the start line to the parallel line, turning, and skating back to the start line in time with the signals emitted from the speaker computer. Subjects continued this pattern of shuttle skating until they could no longer skate (volitional exhaustion) or they failed to reach the line in time with the speaker signals on two successive occasions (disqualification).

HR was monitored and recorded every five seconds using Polar Accurex Plus heart rate monitors (Polar Electro Oy, Kempele, Finland). The computer data were transferred with Polar Interface Plus and Polar Training Advisor V 1.05 software (Polar Electro Oy, Kempele, Finland).

20MSRST results were expressed as total time from the start to the point of volitional exhaustion or disqualification, speed (km · h−1) of the last stage completed and maximum HR in the test.

Match

Heart rate (HR) was monitored and recorded every five seconds in one tournament match. The following heart rate variables were analysed: peak HR, peak HR relative to maximum (HRmax), mean HR, and mean HR relative to HRmax. Furthermore, the participation time in each period, as well as the total participation time in the match, was recorded for each player.

Simulation test

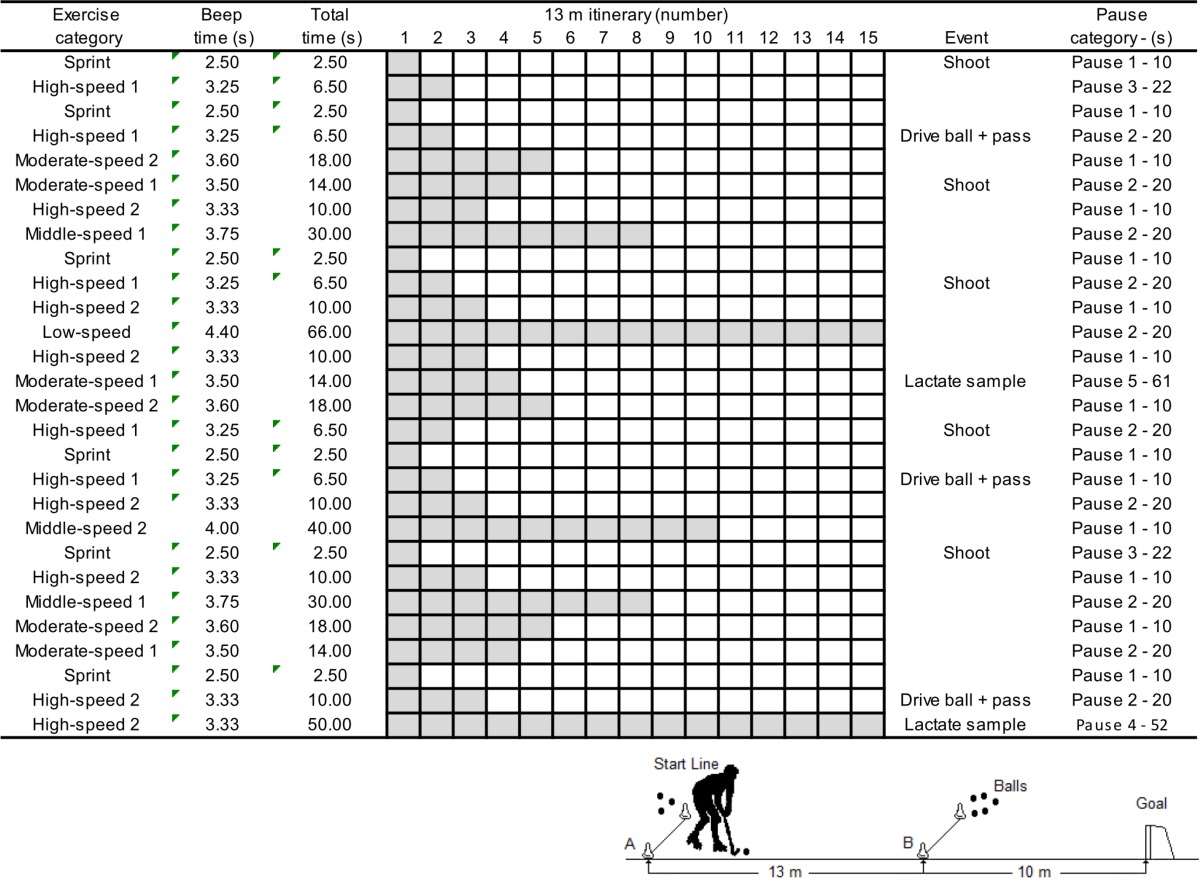

The test was conducted in a rink hockey sports hall. The participants were required to skate between two lines, 13 m apart, and the test lasted for 15 minutes. The test included basic rink hockey skills such as shooting, drive balls and passing. Some balls were placed near the lines, and a rink hockey goal was placed 10 metres from the second line. An intermittent pattern including exercise (44.80%) and pause phases (55.20%), as well as basic rink hockey skills, was repeated throughout the test. The total distance skated was 1521 metres. The exercise and pause phases were designed to be similar to the activity pattern typically shown in rink hockey match play based on previous time-motion analysis [6]. Different exercise and pause categories were established (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

CATEGORIES OF EXERCISE AND PAUSES, SPEED, DISTANCE AND TIME DURING THE SIMULATION TEST

| Exercise category | Speed | Distance | Total Time | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (m·s−1) | (m) | (%) | (s) | (%) | |

| Sprint | 5.20 | 78 | 5.13 | 15.0 | 1.66 |

| High-speed 1 | 4.00 | 130 | 8.55 | 32.5 | 3.61 |

| High-speed 2 | 3.90 | 429 | 28.21 | 109.9 | 12.22 |

| Moderate-speed 1 | 3.71 | 156 | 10.26 | 42.0 | 4.66 |

| Moderate-speed 2 | 3.61 | 195 | 12.81 | 54.0 | 6.00 |

| Middle-speed 1 | 3.47 | 208 | 13.68 | 60.0 | 6.66 |

| Middle-speed 2 | 3.25 | 130 | 8.55 | 40.0 | 4.44 |

| Low-speed | 2.95 | 195 | 12.81 | 50.0 | 5.55 |

| Pause category | Duration (s) | Number (n) | (%) | Total Time (s) | (%) |

| Pause 1 | 10 | 14 | 50.00 | 140 | 15.60 |

| Pause 2 | 20 | 10 | 35.70 | 200 | 22.20 |

| Pause 3 | 22 | 2 | 7.14 | 44 | 4.87 |

| Pause 4 | 52 | 1 | 3.57 | 52 | 5.76 |

| Pause 5 | 61 | 1 | 3.57 | 61 | 6.77 |

Skating speeds during the exercise phases and the duration of the pauses were dictated by an audio signal from a computer using software developed for this purpose. The software was programmed with LabWindows CVI 7.1 (National Instruments Corporation, USA). Exercise, pause phases and events during all tests were developed according to the design proposed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

SCHEMATIC REPRESENTATION OF SIMULATION TEST PROTOCOL

|

|---|

The subjects were verbally informed about the itinerary, subsequent intensity and technical events during the test. Before the test, all subjects performed the same 20-minute warm-up, which included 10 minutes of stretching and 10 minutes of intermittent skating, including sprints.

Heart rate, volume of oxygen uptake, volume of carbon dioxide produced, ventilation, respiratory exchange ratio, and breathing frequency were measured using the MedGraphics VO2000 portable metabolic test system (Medical Graphics Corporation, U.S.A.). Measurements were taken breath-by-breath throughout the test. All analysers were calibrated before each trial with gases of known concentrations. The computer data were transferred with BreezeSuite software (Medical Graphics Corporation, U.S.A.). Blood samples were drawn from the subject's fingertip by pin prick and were analysed for whole blood lactate concentration using an Analox micro-stat P-LM4 (Analox Instruments, London, England). The same devices were used in all three phases of the study.

Maximum heart rate

Maximum HR (HRmax) was considered the maximum registered value of each subject during the entire study (20MSRST, match and simulation test).

Data analysis

Graphical analysis was performed with Microsoft® Excel 2002, and means and standard deviations were calculated. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS® V13.0. Differences between maximal heart rate in 20MSRST, match and ST were calculated by the Kruskal-Wallis H test for several independent samples. Mean heart rate in match and ST was analysed by the Mann-Whitney U test for two independent samples.

RESULTS

20-metre multi-stage shuttle roller skate test. Performance in 20MSRST is shown in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

RESPIRATORY AND METABOLIC PARAMETERS IN SIX RINK HOCKEY PLAYERS DURING THE STUDY.

| Test | Parameters | Mean ± SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20MSRST | Time | min | 14.4 ± 0.6 |

| Speed | km · h−1 | 15.4 ± 0.3 | |

| Peak HR | beats · min−1 | 190.5 ± 7.4 | |

| % HRmax | 99.9 ± 0.6 | ||

| Match | Peak HR | beats · min−1 | 188.3 ± 5.6 |

| % HRmax | 98.7 ± 0.8 | ||

| Mean HR | beats · min−1 | 167.2 ± 3.4 | |

| % HRmax | 87.6 ± 0.7 | ||

| Simulation Test | Peak HR | beats · min−1 | 189.2 ± 6.2 |

| % HRmax | 99.3 ± 0.9 | ||

| Mean HR | beats · min−1 | 165.2 ± 4.6 | |

| % HRmax | 86.3 ± 0.8 | ||

| Peak VE | L · min−1 | 111.0 ± 8.8 | |

| Mean VE | L · min−1 | 70.3 ± 14.0 | |

| % VEmax | 61.1 ± 8.8 | ||

| Peak VO2 | L · min−1 | 4.1 ± 2.1 | |

| mL · kg−1 · min−1 | 56.3 ± 8.4 | ||

| mL · kg-0.75 · min−1 | 164.1 ± 12.4 | ||

| Mean VO2 | L · min−1 | 2.9 ± 0.8 | |

| mL · kg−1 · min−1 | 40.9 ± 7.9 | ||

| mL · kg-0.75 · min−1 | 119.2 ± 13.8 | ||

| % VO2max | 69.1 ± 9.3 | ||

| Mean RER | 0.9 ± 0.1 | ||

| [La]1 | mmol · L−1 | 5.2 ± 1.0 | |

| [La]2 | mmol · L−1 | 7.2 ± 1.3* | |

Note: RER = respiratory exchange ratio.

Significant difference (P < 0.05) between [La]2 and [La]1

Match

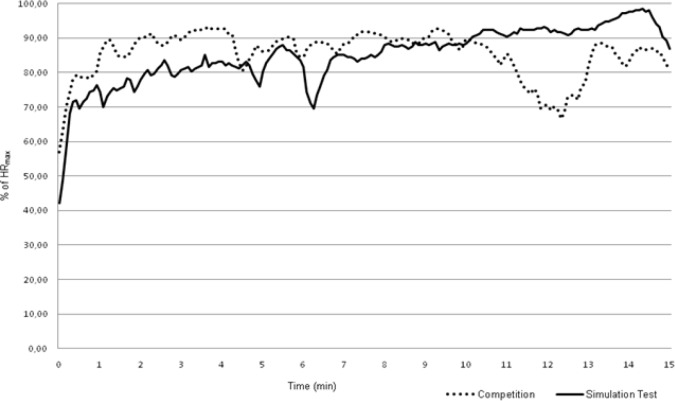

Heart rate behaviour during the competition showed the typical pattern of the intermittent exercise with phases where maximal heart rate was reached, recovery phases, and an elevated average heart rate (Figure 1 and Table 3).

FIG. 1.

INDIVIDUAL HEART RATE, EXPRESSED IN PERCENTAGE OF MAXIMAL HEART RATE OF ONE PARTICIPANT FOR A PERIOD OF 15 MIN EXERCISE DURING THE COMPETITION (MEAN 85.45%) AND SIMULATION TEST (MEAN 84.98%)

Heart rate

Maximum HR was 190.7 ± 7.2 beats · min−1. There were no differences in peak heart rate between 20MSRST 190.5 ± 7.4 beats · min−1, match 188.3 ± 5.6 beats · min−1 and ST 189.2 ± 6.2 beats · min−1. Similarly, no differences were observed in mean HR between ST and match (165.2 ± 4.6 vs 167.2 ± 3.4 beats · min−1, or 86 vs 87% HRmax).

Performance in ST

Respiratory and metabolic parameters during the simulation test (peak and mean values) are shown in Table 3.

Energy expenditure

Total oxygen uptake after 15 minutes of the ST was 44.4 ± 11.5 L. The test yielded an energy expenditure of 899.1 ± 232.9 kJ, and energy power was 59.9 ± 15.5 kJ · min−1 or 3596.4 ± 931.2 kJ · h−1.

DISCUSSION

The simulation test was designed as a controlled field test to simulate the activity patterns observed during a rink hockey match. There were no significant differences between peak heart rate in 20MSRST, ST and competition. In addition, no significant differences were observed in mean HR between ST and competition. The heart rate response during ST was similar to the levels observed during a rink hockey match (Figure 1).

This finding was the basis for extrapolating the results from the test to competition. Previous studies have shown that heart rate stays between 85 and 88% of HRmax during the game (first and second half), and that the intensity remains constant throughout the whole game [7, 19]. Differences in HR are not observed among player positions (defenders, forwards) in the field [7.19]. As HR was constant during the whole game, one time period of 15 minutes for the ST may be enough to predict rink hockey demands during the game. With this short duration, it is easier to motivate the players to participate in the tests than with a longer duration similar to competition.

Maximum HR was 190.7 ± 7.2 beats · min−1. Five subjects exhibited their maximum HR in 20MSRST and one in ST. The peak HR reached in ST corresponded to 99% of that reached in 20MSRST, indicating that ST can be used to determine individual maximal heart rate. Heart rate responses (mean and peak) during the ST and match situations were similar to those reported during rink hockey matches in previous studies, where mean HR was between 85 and 88% of HRmax, and maximal HR was close to 100% [7, 19].

Blood lactate levels during the test (5.2 ± 01.0 mmol · L−1 in the middle and 7.2 ± 1.0 mmol · L−1 at the end) were comparable to but slightly higher than those obtained during rink hockey matches (around 4.5–5.5 mmol · L−1 and 5.5–6.5 mmol · L−1) at the end of the games [19]. Blood lactate concentration probably reflects activities immediately before blood sampling [3]. In previous studies relating heart rate and lactate concentration in competition, values of 4.4 mmol · L−1 during the first half and 4.7 mmol · L−1 during the second half corresponded to a mean HR of 93 and 92% of HRmax, respectively, during the four minutes prior to the sampling [19]. During ST, values obtained from the second sample were higher than the mean values obtained in competition. This sample was obtained after a maximal effort of 50 seconds of high-intensity exercise at the end of the test (High-speed 2, Table 2) where maximum HR was reached. Maximum effort and maximum HR are also reached in competition frequently [7, 19]. Accordingly, at certain time points after intense exercise, lactate levels in competition could be similar to those obtained at the end of the ST. This phenomenon has been observed by Bangsbo [5] in elite level soccer matches, where individual values frequently exceed 10 mmol · L−1 during match play after high-intensity phases. This blood lactate concentration reflects an important contribution of glycolysis, especially at the end of the test. This situation can also occur occasionally during a rink hockey game, because maximal heart rate is frequently reached. New studies in rink hockey matches are necessary, particularly those analysing blood lactate concentration after high-intensity phases.

Peak ventilation was 111.0 ± 8.8 L · min−1, with a range of 100–122 L · min−1. These values are lower than those previously reported in soccer [12, 13]. However, maximal ventilation in specific field tests could be lower than in classical laboratory protocols because it may be harder to work to exhaustion when simultaneously performing technical skills [13]. Mean ventilation was 70.3 ± 14.0 L · min−1, which was approximately 60% of VEmax.

Maximal oxygen uptake was 56.3 ± 8.4 mL · kg−1 · min−1, which is comparable to VO2max values obtained from rink hockey players, with values between 50 and 60 mL · kg−1 · min−1 in maximal treadmill running tests in the laboratory [18], as well as values obtained from field test skating using a portable metabolic test system [19]. Mean oxygen uptake was 2.9 ± 0.8 L · min−1 or 40.9 ± 7.9 mL · kg−1 · min−1, which indicates that on average, subjects operated at 70% of VO2max during the ST. The same average oxygen uptake was reported in soccer match play [5].

The simulation test enabled an investigation of the physiological responses to intermittent high-intensity exercise in rink hockey players. Extrapolating these results to competition, the average work rate during a rink hockey match is approximately 85–88% of maximal HR, and 70% of maximal oxygen uptake. The mean energy expenditure during match play (estimated from ST results) is 59.9 ± 15.5 kJ · min−1, with a range of 43–88 kJ · min−1. For an entire match, this would correspond to between 2.39 and 3.59 MJ for a participation time between 40 and 60 minutes. Match demands of rink hockey are comparable to field hockey, with an oxygen uptake of 2.26 L · min−1 and an estimated energy expenditure ranging from 36 to 50 kJ · min−1 [17], or 61 kJ · min−1 (left corner forward position) to 83 kJ · min−1 (centre midfield position) in elite male players [8].

CONCLUSIONS

The present study showed that the specific test closely simulates the demands of competitive rink hockey. During the test, aerobic and anaerobic energy systems are highly stressed. The simulation test is a valuable tool for studying metabolic responses to intermittent high-intensity exercise in rink hockey players.

Conflict of interest

non declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atkins S.J. Performance of the yo-yo intermittent recovery test by elite professional and semiprofessional rugby league players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2006;20:222–225. doi: 10.1519/R-16034.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aziz A.R, Tan F.H.Y, Teh K.C. A pilot study comparing two field tests with the treadmill run test in soccer players. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2005;4:105–112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bangsbo J, Norregaard L, Thorso F. Activity profile of competition soccer. Can. J. Sport Sci. 1991;16:110–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bangsbo J, Norregaard L, Thorso F. The effect of carbohydrate diet on intermittent exercise performance. Int. J. Sports Med. 1992;13:152–157. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1021247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bangsbo J. Energy demands in competitive soccer. J. Sports Sci. 1994;12:5–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blanco A, Enseñat A, Balagué N. Hockey sobre patines: análisis de la actividad competitiva. RED, Revista de Entrenamiento Deportivo. 1993;7:9–17. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blanco A, Enseñat A. Hockey sobre patines: cargas de competición, RED. Revista de Entrenamiento Deportivo. 2002;12:21–26. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyle P.M, Mahoney C.A, Wallace W.F. The competitive demands of elite male field hockey. J. Sport. Med. Phys. Fit. 1994;34:235–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brewer J, Ramsbottom R, Williams C. Multistage fitness test. Leeds: National Coaching Foundation; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castagna C, Impellizzeri F.M, Belardinelli R, Abt G, Coutts A, Chamari K, D'Ottavio S. Cardiorespiratory responses to Yo-yo Intermittent Endurance Test in nonelite youth soccer players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2006;20:326–330. doi: 10.1519/R-17144.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Girard O, Chevalier R, Habrard M, Sciberras P, Hot P, Millet G.P. Game analysis and energy requirements of elite squash. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2007;21:909–914. doi: 10.1519/R-20306.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoff J, Wisløff U, Engen L.C, Kemi O.J, Helgerud J. Soccer specific aerobic endurance training. Br. J. Sports Med. 2002;36:218–221. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.36.3.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kemi O.J, Hoff J, Engen L.C, Helgerud J, Wisløff U. Soccer specific testing of maximal oxygen uptake. J. Sport Med. Phys. Fit. 2003;43:139–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Léger L, Lambert J. A maximal 20-m shuttle run test to predict VO2 max. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 1982;49:1–12. doi: 10.1007/BF00428958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Léger L, Mercier D, Gadoury C, Lambert J. The multistage 20 metres shuttle run test for aerobic fitness. J. Sports Sci. 1988;6:93–101. doi: 10.1080/02640418808729800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nicholas C.W, Nuttall F.E, Williams C. The Loughborough Intermittent Shuttle Test: a field test that simulates the activity pattern of soccer. J. Sports Sci. 2000;18:97–104. doi: 10.1080/026404100365162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reilly T, Borrie A. Physiology applied to field hockey. Sports Med. 1992;14:10–26. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199214010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodríguez F.A, Martín R, Hernández J. Prueba máxima progresiva en pista para valoración de la condición aeróbica en hockey sobre patines. Apunts: Educació Física i Esports. 1991;23:63–70. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yagüe P. Hockey sobre patines; Demandas fisiológicas, perfil fisiológico y valoración funcional del jugador; University of Oviedo: Oviedo; 2007. Phd. Thesis. [Google Scholar]