Abstract

The purpose of this study was to investigate the relationship between biomechanical variables and running economy in North African and European runners. Eight North African and 13 European male runners of the same athletic level ran 4-minute stages on a treadmill at varying set velocities. During the test, biomechanical variables such as ground contact time, swing time, stride length, stride frequency, stride angle and the different sub-phases of ground contact were recorded using an optical measurement system. Additionally, oxygen uptake was measured to calculate running economy. The European runners were more economical than the North African runners at 19.5 km · h−1, presented lower ground contact time at 18 km · h−1 and 19.5 km · h−1 and experienced later propulsion sub-phase at 10.5 km · h−1,12 km · h−1, 15 km · h−1, 16.5 km · h−1 and 19.5 km · h−1 than the European runners (P < 0.05). Running economy at 19.5 km · h−1 was negatively correlated with swing time (r = -0.53) and stride angle (r = -0.52), whereas it was positively correlated with ground contact time (r = 0.53). Within the constraints of extrapolating these findings, the less efficient running economy in North African runners may imply that their outstanding performance at international athletic events appears not to be linked to running efficiency. Further, the differences in metabolic demand seem to be associated with differing biomechanical characteristics during ground contact, including longer contact times.

Keywords: athletes, biomechanics, stride angle, ethnicity, running efficiency, endurance

INTRODUCTION

North African runners are world renowned for their success in middle-and long-distance running. To date, North African countries have more world champions in middle-distance running than other any region in the world including East Africa. Further, male runners originating from North Africa have won twice as many world championship medals in the 1500 m than any other ethnic population. Most recently, North Africans have won the Olympic gold and bronze medals in the 1500 m during London 2012.

To explain their success, the ability to maintain a relatively high maximal aerobic velocity during running, together with advantageous psychological conditioning, has been hypothesized [19]. However, it seems that their outstanding performance on the track at international athletic events is not linked to metabolic differences. A few researchers have described the factors contributing to running performance in North African runners [3, 19]; however, these researchers failed to examine running biomechanics in these athletes.

During running, various biomechanical factors contribute to performance by influencing running economy [24]. Longer ground contact times are correlated with higher O2 [17, 22], whereas small vertical oscillation [25], longer strides, smaller changes in velocity during ground contact and lower peak ground reaction forces [1] have been related to economical runners. North African runners may exhibit running gait that positively contributes to their superior performance.

To date, the influence of biomechanical variables on running economy in runners originating from North Africa remains unclear. Thus, this study aimed to determine whether biomechanical characteristics such as ground contact time, swing time, stride length and frequency, stride angle and the distribution of the different sub-phases during ground contact might be instrumental in the exceptional North African running performance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Twenty-one high-level runners (8 North African runners of Moroccan descent, 13 European runners of Spanish descent) were recruited for the study from local running clubs. The mean age was 29.9 ± 6.5 years for the North Africans and 27.9 ± 6.4 years for the Europeans. Performance in their primary distance was rated according to the scoring procedures of the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF score) [23]. The two groups were of the same performance standard with no significant difference in mean current IAAF scores in their primary distance or in their best recent 10-km record (North Africans 937 ± 53 points and 31.2 ± 1.1 min; Europeans 960 ± 58 points and 31.7 ± 1.4 min).

Before participation, subjects underwent a medical examination to ensure that they were free of cardiovascular, musculoskeletal and metabolic disease. The Ethics Committee for Research on Human subjects of the University of the Basque Country (CEISH/GIEB) approved this study, which was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (October 2008, Seoul). All athletes were informed about all the tests and possible risks involved and provided written informed consent before testing.

All participants were seasoned competitors and they were tested between May and June 2012, i.e., whilst they were in their peak condition for target competitions of the summer season. Athletes were excluded if they were not currently competing in races or if they possessed an IAAF score lower than 850 points in their primary distance.

24 hours prior to testing, athletes were encouraged to abstain from a hard training session and competition in order to be well rested for the tests. They were also requested to maintain their pre-competition diets throughout the test procedures and to refrain from alcohol and caffeine ingestion for at least 24 hours before testing. All athletes had previous experience with treadmill running, including a thorough familiarization session with the treadmill used for the study.

Anthropometry

Height (cm) and body mass (kg) were determined by the use of a precision stadiometer and balance (Seca, Bonn, Germany) wearing only running shorts. Body mass index (BMI) was determined. Eight skinfold sites (biceps, triceps, subscapular, supraspinale, abdominal, suprailiac, mid-thigh, and medial calf) were measured in duplicate with skinfold calipers (Holtain, Crymych, UK) by the same researcher to the nearest millimetre and the sum of skinfolds was calculated.

Treadmill velocity test

All participants completed a maximal incremental running test at 1% slope on a treadmill (ERGelek EG2, Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain), which started at 9 km · h−1 without previous warm up. The velocity was increased by 1.5 km · h−1 every 4 minutes until volitional exhaustion, with a minute recovery between each stage. The treadmill was calibrated using a measuring wheel (ERGelek, Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain) with a measurement error <0.5 m per 100-m interval. All testing sessions were performed under similar environmental conditions (20-24°C, 45-55% relative humidity).

During the test, respiratory variables were continuously measured using a gas analyser system (Ergocard, Medisoft, Sorinnes, Belgium) calibrated before each session. Volume calibration was performed at different flow rates with a 3 L calibration syringe (Medisoft, Sorinnes, Belgium) allowing an error ≤ 2%, and gas calibration was performed automatically by the system using both ambient and reference gases (CO2-4.10%; O2-15.92%) (Linde Gas, Germany). O2 data collected during the last 30 seconds of each workload were averaged and designated as the steady-state value for data analysis. The coefficient of variation of the variables measured with the Medisoft Ergocard gas analyser ranged from 1.0 to 3.4%.

To reduce the influence of body mass, O2 was normalized using allometric scaling and expressed as ml · kg0.75 · min−1 [8]. Moreover, running economy (RE) was determined as steady-state O2 per distance covered (ml · kg−1 · km−1) [7]. Heart rate (HR) was recorded continuously by a heart rate monitor (Polar RS800, Kempele, Finland) and rating of perceived exertion (RPE) was assessed immediately after each exercise stage using the 10-point Borg scale [2].

Athletes were considered to have attained their maximal ability, and therefore reached their O2max, when three of the following criteria were fulfilled: 1) a plateau in O2 occurred; 2) Respiratory exchange ratio (RER) > 1.15; 3) HR within 5 beats · min−1 of theoretical maximal HR (220-age); 4) lactate concentration > 8 mmol · L−1; 5) RPE= 10.

Peak treadmill velocity (PTV; in km · h−1) was calculated as follows taking every second into account:

PTV= Completed full intensity (km · h−1) + [(seconds at final velocity · 240 s−1-) · 1.5 km · h−1]

Biomechanics

Ground contact time (tc), defined as the time from when the foot contacts the ground to when the foot toes off the ground; swing time (tsw), defined as the time from toe off to initial ground contact of consecutive footfalls of the same foot; stride length, defined as the length the treadmill belt moves from toe off to initial ground contact in successive steps; stride frequency, defined as the number of ground contact events per second; stride angle, defined as the angle of the parable tangent derived from the movement of a stride; and the percentage of ground contact time at which the different sub-phases of the stance phase occur (initial contact, midstance and propulsion) were measured for every step during the treadmill velocity test using an optical measurement system (Optojump-next, Microgate, Bolzano, Italy). During the stance phase of the gait cycle, the initial contact sub-phase corresponds to the time from when the foot contacts the ground to foot flat; the midstance sub-phase is from foot flat to heel off; and the propulsive sub-phase is from heel off to toe off. The coefficient of variation of the variables measured with the Opto-jump-next ranged from 1.0 to 7.6%.

Statistics

All values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and the statistical analyses of data were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 15.0 software package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data were screened for normality of distribution and homogeneity of variances using a Shapiro-Wilk normality test and Levene's test, respectively. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measures was applied to determine differences between groups. If a main effect was detected, post hoc comparisons were made with Tukey's honestly significant difference test for pairwise comparisons.

The magnitude of differences or effect size (ES) were calculated according to Cohen [5] and interpreted as small (>0.2 and <0.6), moderate (≥0.6 and <1.2) and large (≥1.2 and <2) according to the scale proposed by Hopkins et al. [9]. Pearson's product-moment correlations were performed to analyse the relationship between RE and the biomechanical variables at 19.5 km · h−1, which was the velocity eliciting the 10-km race pace in both groups of athletes. Significance for all analyses was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Descriptive characteristics and maximal treadmill test results for both North African and European runners are listed in Table 1. No significant anthropometric differences were found between the North African and European runners. Similarly, there were no physiological differences in maximal values of O2, HR and RER.

TABLE 1.

SUBJECT CHARACTERISTICS AND MAXIMAL TEST RESULTS OF THE NORTH AFRICAN (N = 8) AND EUROPEAN RUNNERS (N = 13)

| North African runners (n = 8) | European runners (n = 13) | ES | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 29.9 ± 6.5 | 27.9 ± 6.4 | 0.31 |

| PTV, km · h−1 | 20.8 ± 0.7 | 20.7 ± 1.1 | 0.10 |

| 10-km time, min | 31.2 ± 1.1 | 31.7 ± 1.4 | 0.47 |

| IAAF score, points | 937 ± 53 | 960 ± 58 | 0.41 |

| Height, cm | 177.7 ± 5.3 | 176.7 ± 5.3 | 0.18 |

| Mass, kg | 64.3 ± 5.9 | 64.7 ± 3.9 | 0.07 |

| BMI | 20.8 ± 1.4 | 20.3 ± 1.0 | 0.41 |

| Σ 8 skinfold, mm | 47.4 ± 18.1 | 46.6 ± 12.0 | 0.05 |

| VO2max, mL · kg−1 · min−1 | 66.4 ± 3.7 | 63.1 ± 4.0 | 0.85 |

| HRmax, beats · min−1 | 186.5 ± 6.3 | 187.1 ± 5.8 | 0.09 |

| RERmax | 1.14 ± 0.07 | 1.20 ± 0.06 | 0.92 |

Note: Values are means ± SD. n, number of subjects; PTV, peak treadmill velocity; BMI, body mass index; Σ 8 skinfold, (biceps, triceps, subscapular, supraspinale, abdominal, suprailiac, mid-thigh, and medial calf); VO2max, maximum oxygen uptake; HRmax, maximum heart rate; RERmax, maximum respiratory exchange ratio. ES, effect sizes (Cohen's d). *Significantly different from PTV (P < 0.05).

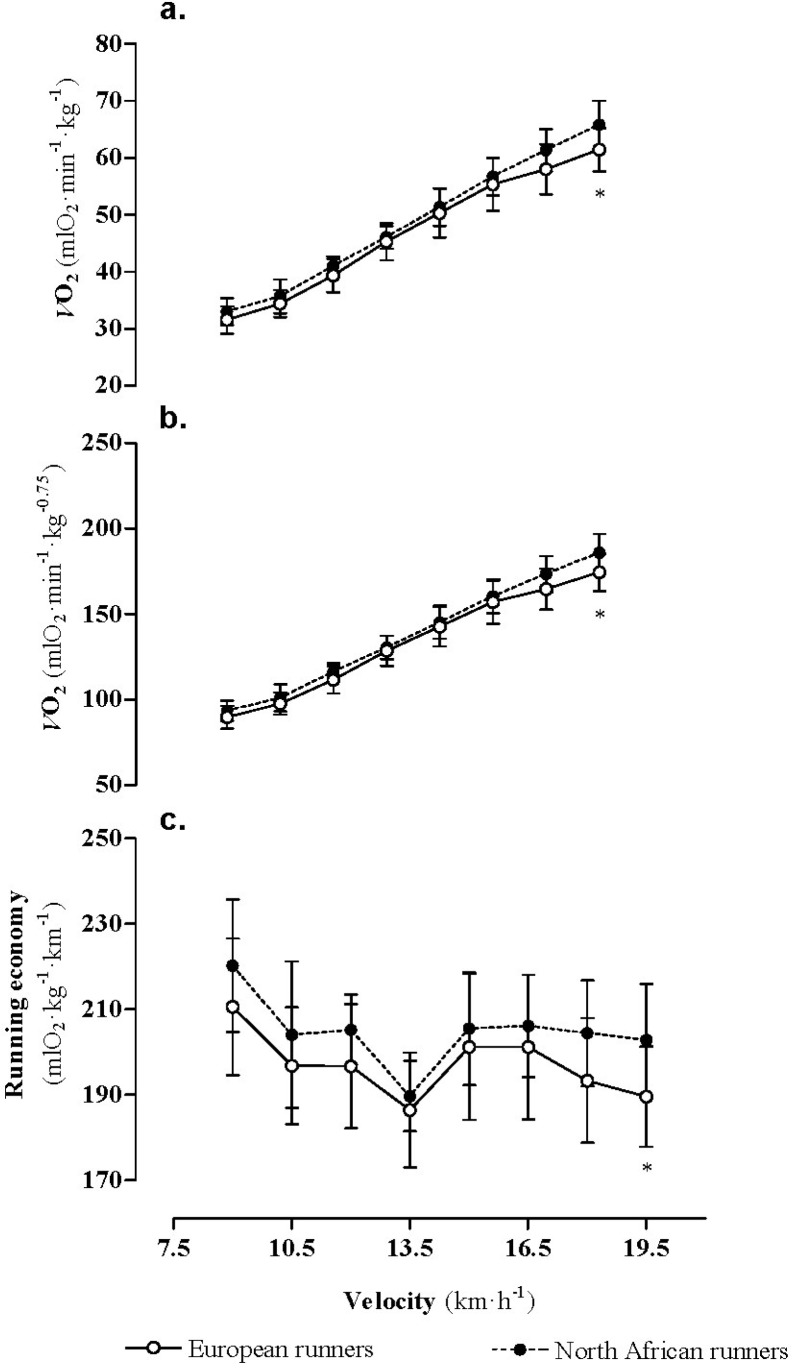

The European runners were significantly more economical than their North African counterparts at 19.5 km · h−1 according to O2 (relative to body mass and relative to body mass0.75) and the oxygen cost of running per distance (ml · kg−1 · km−1) (P < 0.05; ES = 1.07) (Figure 1).

FIG. 1.

OXYGEN UPTAKE (VO2) AND RUNNING ECONOMY AT DIFFERENT SET VELOCITIES IN THE NORTH AFRICAN (N = 8) AND EUROPEAN RUNNERS (N = 13). Note: *Significantly different from North African runners (P < 0.05).

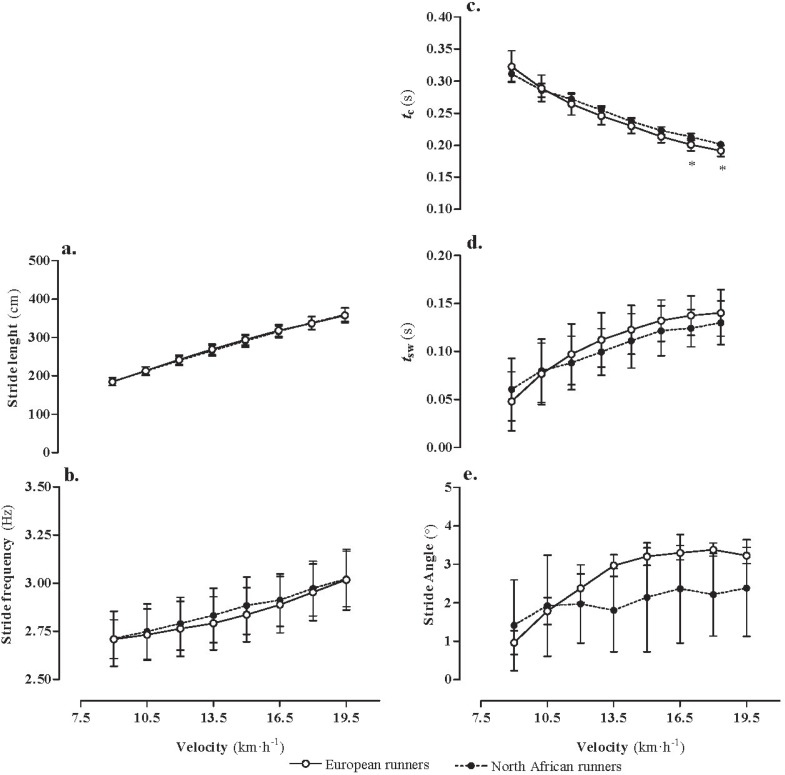

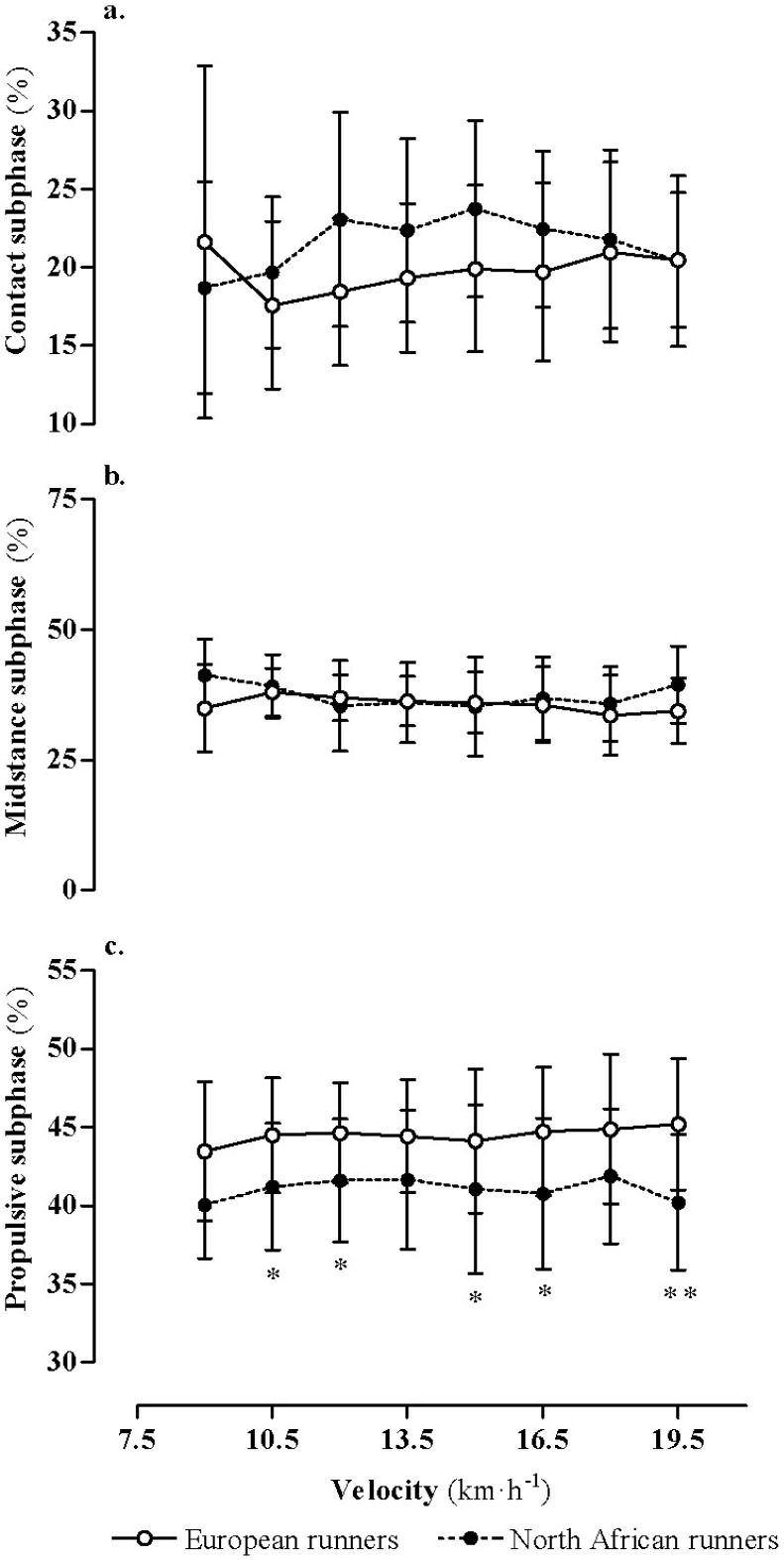

Biomechanically, the European runners presented lower tc at 18 km · h−1 (P < 0.05; ES = 1.09) and 19.5 km · h−1 (P < 0.05; ES = 0.92) than the North African runners (Figure 2a.). However, no differences were found in stride length, stride frequency, tsw or stride angle between groups at any velocity (Figure 2b, 2c, 2d and 2e, respectively). With respect to the different sub-phases during ground contact, European runners experienced an earlier propulsive sub-phase than the North African group during ground contact at 10.5 km · h−1 (P < 0.05; ES = 0.99), 12 km · h−1 (P < 0.05; ES = 0.98), 15 km · h−1 (P < 0.05; ES = 0.89), 16.5 km · h−1 (P < 0.05; ES = 0.88) and 19.5 km · h−1 (P < 0.01; ES = 1.32) (Figure 3c).

FIG. 2.

STRIDE LENGTH (A.), STRIDE FREQUENCY (B.), CONTACT TIME (TC) (C.), SWING TIME (TSW) (D.) AND STRIDE ANGLE (E.) AT DIFFERENT SET VELOCITIES IN THE NORTH AFRICAN (N = 8) AND EUROPEAN RUNNERS (N = 13)Note: *Significantly different from North African runners (P < 0.05)

FIG. 3.

PERCENTAGE OF THE GROUND CONTACT AT WHICH THE CONTACT SUBPHASE (A.), MIDSTANCE SUBPHASE (B.) AND PROPULSIVE SUB-PHASE (C.) OCCUR AT DIFFERENT SET VELOCITIES IN THE NORTH AFRICAN (N = 8) AND EUROPEAN RUNNERS (N = 13). NOTE: *Significantly different from North African runners (P < 0.05), * (P < 0.01).

There were significant correlations between RE and some biomechanical variables at 19.5 km · h−1. RE was positively correlated with tc (P < 0.05; r = 0.53), whereas it was negatively correlated with tsw (P < 0.05 r = −0.53) and the stride angle (P < 0.05 r = -0.52) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

NTER-RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN BIOMECHANICAL VARIABLES AND RUNNING ECONOMY AT 19.5 km·h−1 (N = 21).

| RE at 19.5 km·h−1 | r | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Contact time | 0.53 | 0.013 |

| Swing time | −0.53 | 0.014 |

| Stride length | −0.40 | 0.074 |

| Stride frequency | 0.35 | 0.122 |

| Stride angle | −0.52 | 0.016 |

| Contact sub-phase | −0.05 | 0.828 |

| Mid-stance sub-phase | 0.01 | 0.970 |

| Propulsive sub-phase | 0.02 | 0.906 |

Note: RE, running economy; r, Correlation co-efficien

DISCUSSION

The major finding of this study was that there were significant physiological and biomechanical differences that discriminated between the North African and European runners at different submaximal velocities. The European runners were more economical than the North African runners at increased running velocities, not only according to O2 and RE, but also when O2 was normalized to body mass0.75. Previous findings comparing RE in different groups of African athletes have been controversial, because no differences were found in the energy cost of running between South African Black and Caucasian runners [4, 6, 11], whereas a better RE was reported in Kenyan [20] and Eritrean runners [13] at training and racing pace for competitions of 10-12 km when compared to their European counterparts.

In this study, when ·O2 was normalized to body mass0.75, the differences persisted between both groups, indicating that other factors may largely contribute to differences in RE in both groups of runners and are not solely a result of anthropometric variables. It is known that the economy of movement and running performance are greatly influenced by the size of the athlete [15, 22]. Thus, our findings may be representative of intrinsic differences between both groups of athletes as significant anthropometric differences were absent.

A number of biomechanical factors have been found to influence RE [22]. It has been reported that particular biomechanical patterns characterized by longer stride lengths are associated with economical runners [1]. We did not find differences in the stride length or stride frequency at any velocity, as this would be expected for anthropometrically similar athletes. Additionally, these biomechanical features were not related to RE at 19.5 km · h−1 in this study, whereas both t sw and stride angle were significantly associated with RE at this velocity. Stride angle comprises stride length and the maximum height the foot reaches during the swing phase. Greater stride angles imply a longer tsw with greater hip, knee and ankle flexion and shorter tc (characterized by effective energy transfer during the propulsive sub-phase). It appears that tsw and stride angle may be an effective discriminator of efficient gait patterns during running in competitive well-trained athletes. However, there were no differences in tsw and stride angle between North African and European runners. Therefore, the observed more efficient running pattern in European runners in this study may be closely related to ground contact variables.

The European runners had shorter tc than the North African runners at increased velocities. This finding agrees with previous studies [17, 25] and confirms that efficient runners are characterized by lower tc. It has been found that tc and peak medial force are correlated with sub-maximal O2 and that smaller antero-posterior and vertical forces in the vertical component of the ground contact are associated with economical runners [25]. Thus, the forces experienced during ground contact of the gait cycle will greatly determine the metabolic demand [22]. This is illustrated in this study as a positive correlation was found between tc and RE. Other authors have similar findings with studies investigating trained and untrained runners [10, 17, 25]. These data further suggest that tc may be a discriminator between economical and less economical runners regardless of gender, athletic ability or ethnic origin.

Interestingly, the percentage of the gait cycle at which the propulsion sub-phase of the stance phase occurred was higher in North African runners when compared to the European runners. During the propulsive sub-phase force is applied from the lower limbs to the ground to obtain forward horizontal displacement during running and has been suggested to be related to RE [22]. Although there is no formula for the most economical running form, several studies investigating the biomechanics of running gait have proposed that gait pattern may be related to the energy cost of running [18]. It has been observed that the percentage of the gait cycle at which toe off occurs depends not only on the velocity, but also on the level of the athlete [16]. Thus, it has been observed that world-class runners toe off earlier than runners of lower athletic ability [14], suggesting that an earlier propulsion sub-phase during the gait cycle is a desirable running feature. The North African runners in this study exhibited a later propulsive sub-phase, which in combination with longer tc may contribute towards a less efficient RE. However, the absence of a significant correlation between the propulsive sub-phase and RE at 19.5 km · h−1 implies that tc may be the major discriminator between North African and European runners in this study with regard to differences in metabolic demand during running.

A previous study has reported that factors such as greater aerobic ability and stronger psychophysiological conditioning may enable North African runners to outperform their European counterparts on the track [19]. In this regard, a moderate effect size (ES = 0.85) was found between the groups despite the absence of a significant difference in O2max. This ES may be biologically relevant, as a 1% change in O2max has been found to influence running performance [21]. Thus, North African runners in this study may compensate their less efficient RE when compared to European runners of matched ability through a meaningfully greater O2max.

Elite North African runners have performed outstandingly on the track at international athletic events. Despite the high level of runners participating in this study, a possible limitation was that they were 3-4 minutes slower than athletes of an Olympic standard. A question arises whether the physiological and biomechanical responses of the North African runners in this study would be similar to the responses of the best Moroccan and Algerian runners. Assuming the previous statement, our results suggest that the reasons for their superiority appear not to be biomechanical or RE based.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, the less efficient RE at velocity eliciting 10-km race pace in North African runners implies that their outstanding performance on the track at international athletic events appears not to be linked to running efficiency. The differences in metabolic demand at increased velocity were found to be associated with differing biomechanical running patterns. European runners presented shorter tc and an earlier propulsive sub-phase than North African runners at different set velocities. Assuming one could extrapolate these findings, the significant correlations between tc and RE at 19 km · h−1, together with the differences found in tc between the two groups, may imply that ground contact characteristics are the major discriminator between RE in North African and European runners.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by a Basque Government scholarship (ref. BFI08.51) to Jordan Santos-Concejero and by the Department of Physical Education and Sport of the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

There is no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson T. Biomechanics and running economy. Sports Med. 1996;22:76–89. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199622020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borg G. Psychophysical basis of perceived exertion. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1982;14:377–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaouachi M, Chaouachi A, Chamari K, Chtara M, Feki Y, Amri M, Trudeau F. Effects of dominant somatotype on aerobic capacity trainability. Br. J. Sports Med. 2005;39:954–959. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2005.019943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coetzer P, Noakes T.D, Sanders B, Lambert M.I, Bosch A.M, Wiggings T, Dennis S.C. Superior fatigue resistance of elite black South African distance runners. J. Appl. Physiol. 1993;75:1822–1827. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.75.4.1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harley Y.X, Kohn T.A, Gibson A.C, Noakes T.D, Collins M. Skeletal muscle monocarboxylate transporter content is not different between black and white runners. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2009;105:623–632. doi: 10.1007/s00421-008-0942-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Helgerud J. Maximal oxygen uptake, anaerobic threshold and running economy in women and men with similar performances level in marathons. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 1994;68:155–161. doi: 10.1007/BF00244029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Helgerud J, Støren O, Hoff J. Are there differences in running economy at different velocities for well-trained distance runners? Eur. J. App. Physiol. 2010;108:1099–1105. doi: 10.1007/s00421-009-1218-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hopkins W.G, Marshall S.W, Batterham A.M, Hanin J. Progressive statistics for studies in sports medicine and exercise science. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2009;41:3–13. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31818cb278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaneko M, Ito A, Fuchimoto T, Shishikura Y, Toyooka J. Influence of running speed of the mechanical efficiency of sprinters and distance runners. In: Winter D.A, Norman, Wells R.P, Heyes C.K, Patla A.E, editors. Biomechanics IX-B. Champaign: Human Kinetics; 1985. pp. 307–312. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kohn T.A, Essén-Gustavsson B, Myburgh K.H. Do skeletal muscle phenotypic characteristics of Xhosa and Caucasian endurance runners differ when matched for training and racing distances? J. Appl. Physiol. 2007;103:932–940. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01221.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kyröläinen H, Belli A, Komi P.V. Biomechanical factors affecting running economy. Med. Sci. Sport Exer. 2001;33:1330–1337. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200108000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lucia A, Esteve-Lanao J, Oliván J, Gómez-Gallego F, San Juan A.F, Santiago Pérez M, Chamorro-Viña C, Foster C. Physiological characteristics of the best Eritrean runners-exceptional running economy. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2006;31:530–540. doi: 10.1139/h06-029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mann R.A, Hagy J. Biomechanics of walking, running, and sprinting. Am. J. Sports Med. 1980;8:345–350. doi: 10.1177/036354658000800510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marino F, Lambert M.I, Noakes T.D. Superior performance of African runners in warm humid but not in cool environmental conditions. J. Appl. Physiol. 2004;96:124–130. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00582.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Novacheck T.F. Review paper: the biomechanics of running. Gait & Posture. 1998;7:77–95. doi: 10.1016/s0966-6362(97)00038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nummela A, Keränen T, Mikkelsson L. Factors related to top running speed and economy. Int. J. Sports Med. 2007;28:655–661. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-964896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perry J. Anatomy and biomechanics of the hindfoot. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;177:9–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santos-Concejero J, Granados C, Irazusta J, Bidaurrazaga-Letona I, Zabala-Lili J, Badiola A, Gil S.M. Physiological and performance responses of elite North African and European endurance runners to a traditional maximal incremental exercise. Int. Sportmed J. 2013 IN PRESS. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saltin B, Kim C.K, Terrados N, Larsen H, Svedenhag J, Rolf C.J. Morphology, enzyme activities and buffer capacity in leg muscles of Kenyan and Scandinavian runners. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. 1995;5:222–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.1995.tb00038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saunders P.U, Cox A.J, Hopkins W.G, Pyne D.B. Physiological measures tracking seasonal changes in peak running speed. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2010;5:230–238. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.5.2.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saunders P.U, Pyne D.B, Telford R.D, Hawley J.A. Factors affecting running economy in trained distance runners. Sports Med. 2009;34:465–485. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200434070-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spiriev B. IAAF scoring tables 2011. Monaco: Multiprint; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams K.R. Biomechanical factors contributing to marathon race success. Sports Med. 2007;37:420–423. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200737040-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams K.R, Cavanagh P.R. Relationship between distance running mechanics, running economy, and performance. J. Appl. Physiol. 1987;63:1236–1245. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1987.63.3.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]