Abstract

The triple jump is a demanding athletics event that, after an approach run, consists of three consecutive phases: the hop, the bound, and the jump. During the involved three take-off actions a jumper is exposed to increased risk of injury due to the high impact forces from the ground and powerful muscle/tendon efforts, which are further reflected in the internal loads of the lower limb joints. While external ground reactions can possibly be measured using force platforms, in vivo measurements of the internal loads are practically not feasible. The purpose of the paper is to present the development of an effective formulation for the inverse dynamics simulation of the triple jump, based on the jumper dynamical model and non-invasive kinematic recordings of the movement. The developed simulation model serves for the analysis of all the triple jump phases, irrespective of whether the jumper is in flight or in contact with the ground with one of his feet, and is focused on effective assessment of the external reactions on the supporting leg as well as the muscle forces and joint reaction forces in the leg. Some numerical results of inverse dynamics simulation of the triple jump are reported.

Keywords: triple jump, biomechanical loadings, inverse dynamics

INTRODUCTION

The triple jump is a demanding athletics event which, after an approach run, is divided into the hop, step (skip or bound), and jump phases, all executed in one continuous sequence. The hop is a sort of cycling movement – the athlete jumps from one leg, cycles this leg through, and ends on the runway with the same leg. The immediately following step is from the takeoff leg to the opposite leg, and the final jump, from the non-takeoff leg, is very similar to the long jump. The distinct phases must be learned and practised to combine them in one successful (long distance) event. During the three take-off actions a jumper is exposed to increased risk of injury due to the high impact forces from the ground and powerful muscle/tendon efforts, which are further reflected in the internal loads of the lower limb joints. The triple jump is therefore one of the most technically and physically demanding athletic events [11, 13].

The previous studies on triple jump focused mainly either on qualitative analyses of the individual athlete techniques [12], biomechanical loading from the ground [13] or more specific aspects of the optimum phase ratio [16] and function of arm swing motions [2] (see also [1, 11] for a broader review). The present contribution attempts to supplement the studies with the inverse dynamics simulation of the triple jump, aimed at quantitative evaluation of external and internal loads during the movement. The insight into how the muscle forces interact to produce the movement and assessment of the internal loads in lower limb joints may be of importance for better understanding of the triple jump technique and possible injury mechanisms. While inverse dynamics analysis, based on musculoskeletal modelling and non-invasive kinematic recordings, is intensively used in studying the biomechanics and motor control of human movement [8, 14, 15, 17], its applications to triple jump analysis are rare.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Modelling preliminaries

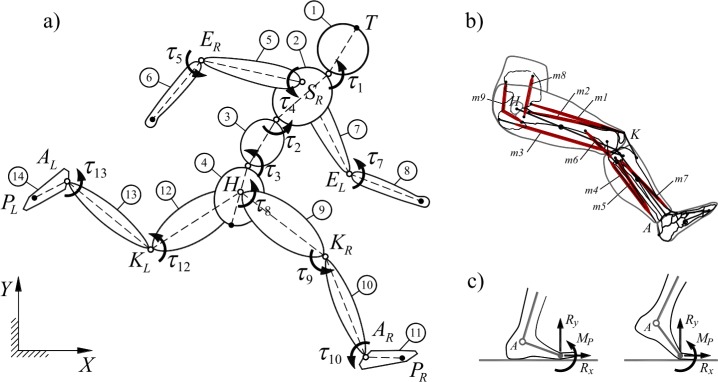

The crucial feature of the present modelling effort is a uniform formulation for the inverse dynamics study of all the distinct phases of triple jump, irrespective of whether the jumper is in flight or in contact with the ground. Under the assumption that the motion of all the body segments is executed, with some exactitude, in the planes parallel to the sagittal plane, a planar model of the jumper is developed, which extends and improves the model used previously in [5]. It is designed as a kinematic structure composed of N=14 rigid segments connected by k=13 ideal hinge joints, branching from the head segment (point T) into the open chain linkages (Fig. 1a). Considering the model as a flier, its number of degrees of freedom is r=3 + k=16. The flier can then contact the ground with one foot, which yields external reaction forces on this particular foot.

FIG. 1.

THE MODELLING ISSUES: A) TORQUE-ACTUATED MODEL, B) LOWER LIMB MUSCLES, C) GROUND REACTIONS

The dynamic equations can conveniently be introduced in n=3 N=42 absolute coordinate p=[x C1 y C1 θ 1 … x CN y CN θ N]T that specify the locations of mass centres and orientations of the segments with respect to the inertial frame XY, and the equations are affected by l=2 k=26 constraint reaction forces λ=[λ 1 … λ l]T(the X and Y components of the joint reaction forces) consequent to l kinematic constraints due to the connections in the joints,.Φ(p) = 0. The matrix form of the dynamic equations is

| 1 |

where are the dynamic equations of unconstrained segments, with the generalized mass matrix M=diag(m 1,m 1, J C1, … m N ,m N,J CN), and the generalized force vector due to the gravitational forces f g=[0 −m 1 g 0 … 0 −m N g 0]T, and where mi and JCi are the mass and the central moment of inertia of the ith segment, and g is the gravity acceleration. The other generalized force vectors are related to: f c−C T λ –joint reactions, where C = ∂Φ/∂p is the l × n constraint matrix, fu– external reactions, and fu – system actuation.

The external reaction components exerted on the foot in contact with the ground are modelled as λ r = [R x R y M p]T, where R x and R y are the X and Y components of the reaction force, and Mp is the reaction force moment about the “end” point P of the foot segment; see Fig. 1c (during the flying phases λr should by principle vanish). The generalized force vector fr can then be represented as , where the n × lr (42 × 3) matrix of distribution of λr in p directions can easily be formulated (not reported here for brevity).

Models of actuation

Two models of actuation are considered. The deterministic model of actuation involves torques u τ = [τ1 … τ13] that represent the resultant muscle action in all k=16 model joints (Fig. 1a). In the nondeterministic model of actuation, k” = 3 torques in the supporting leg are replaced with the action of m=9 muscle forces seen in Fig. 1b, F = [F 1 … F 9]T. Denoted symbolically u τ = [τ′T τ″T]T, where τ″ are the torques in the supporting leg, and τ′ are the k′ = k – k″ = 10 torques in the other joints, the non-deterministic model of actuation is related to u τF = [τ′T F T]T, which is a mixed set of resultant muscle torques and muscle forces. Due to this hybrid model of actuation, attention can be focused on a more detailed analysis of internal loads in the supporting leg, while retrieving the dynamic interaction between the upper body and the locomotion apparatus; see also [5], where a similar methodology was introduced.

The generalized actuation force vector f u in Eq. (1), respectively for the deterministic and nondeterministic models of actuation, is modelled as follows:

| 2 |

where the n×k′ matrix is exactly the same in both cases, and and are of dimensions n×k″ and n×m, respectively. The deterministic and nondeterministic models of actuation are not equivalent, B τ u τ ≠ B τF u τF, and in particular . More strictly, while the muscle forces F in the nondeterministic model must result in the same control torques τ" about the respective joints, the tensile muscle forces contribute to the internal joint reactions λ, represented in Eq. (1) by f c= − C T λ, and the contribution is neglected when the deterministic model of actuation is used. The assessment of joint reactions should therefore include the nondeterministic model of actuation.

The formulation of Bτ is evident. It is a sparse matrix with two nonzero entries, equal to either 1 or −1, in each column [5]. The formulation of in is more challenging. Each muscle in the lower limb must be modelled considering its action on the skeleton segments. Of special importance is accurate identification of the muscle paths relative to the skeleton [9, 21] to determine the muscle moment arms around the joints. Consequently, the effective origin and insertion points must be estimated, where the muscle forces are applied to the model segments. These aspects are discussed in more detail in [4].

RESULTS

Determinate inverse dynamics problem

The developed human body model can be used for the inverse dynamics simulation of the triple jump. The input data for the simulation are measured (numerically smoothed) kinematic characteristics of the movement, p d(t) and ( are not involved). Depending on the actuation model, the inverse dynamics problem that arises is then either determinate or indeterminate. In the determinate inverse dynamics problem the k = 13 resultant muscle torques u τ in all the joints and the l r = 3 external reactions λr on one foot can explicitly be determined (total number of the unknowns equals the number of degrees of freedom of the system, r = k + l r = 16). To achieve this the initial dynamic equations defined in Eq. (1) need to be projected into the space defined by independent coordinates, here q=[x T y T θ 1 … θ 14]T, where X T and y T are the coordinates of point T at the top of the head segment (Fig. 1a), and θ i are as introduced previously in p. The relation p=g(q) leads then to an n×r matrix D =∂g/∂q, which is an orthogonal complement matrix to the l×n constraint matrix C, i.e. CD=0 ⇔ D T C T =0 [5]. The projected dynamic equations are then , where the arising 16 × 3 matrix and the 16 × 13 matrix can be augmented to form an invertible r×r matrix Tr so that

| 3 |

Using the kinematic characteristics of the triple jump, p d(t) and , the time variations λ rd (t) λ d (t) and in the observed motion can explicitly be determined. Note that the solution is valid irrespective of whether the jumper is in flight or in contact with the ground with one of his feet. Evidently, during the flying phases the calculated ground reactions are expected to vanish, which can be treated as a criterion of validity of the simulation model and accuracy of the recorded (and numerically processed) kinematic characteristics.

Indeterminate inverse dynamics problem

The indeterminate inverse dynamics problem (redundant problem in biomechanics [8, 14, 15, 17, 18]) is consequent to control of overactuation in musculoskeletal joints if muscle forces are introduced as actuators. The problem is usually solved using optimization techniques that apply some predetermined criteria to share the muscular joint torques into the individual muscle efforts. For the present hybrid model of actuation u τF = [τ′T F T]T, the redundancy is limited to the supporting leg joints, which yields some modelling peculiarities reported previously in [5]. An improved formulation of this type, which uses τ d(t) from the determinate inverse dynamics, is as follows. The actuation effort represented in the projected dynamic equations, where and , is projected in the directions of control torques uτ, which leads to , where . Following the partitions described in Eq. (2), the problem of distribution of torques in τ” the lower limb joints to the respective muscle forces F can be decomposed to

| 4 |

where and are of dimensions k″×k″(3 × 3) and k″×m (3× 9), respectively. For known from the determinate inverse dynamics solution, Eq. (4) constitutes k″ =3 kalgebraic equations in m=9 unknown F. The redundancy of muscular load sharing, τ″→F, is then commonly addressed by minimizing a cost (objective) function. One popular cost function is that proposed by Crowninshied and Brand [6, 8, 14, 17, 18], , where σ=[σ1 … σm] are the muscle stresses, σj=Fj/A j , and A=diag(A 1, … A m) are the physiological cross-sectional areas (PCSA) of the muscles. Denoting F = A σ, and then , the muscular load sharing problem in the supporting leg can be stated as the following optimization scheme:

| 5 |

where σ min and σ max are the physiologically allowable minimal and maximal values of muscle stresses. In this way a solution σ d (t)and then Fd (t) = A σ d (t) related to the lower limb is found, which substitutes for the resultant muscle force torques τ″ d (t).

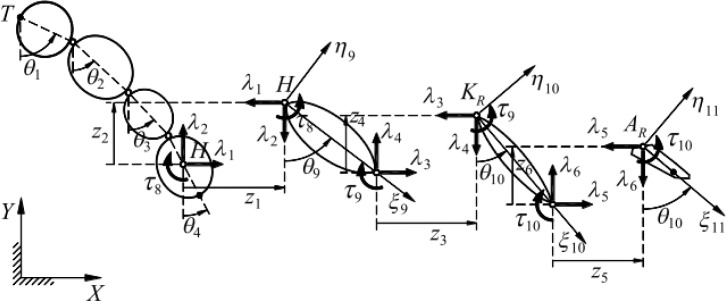

Determination of joint reactions in the supporting leg

Using the muscle forces F d(t) in the supporting leg, assessed from the decomposed indeterminate inverse dynamics problem, and the ground reaction forces λ rd (t) and resultant muscle torques τ′ d (t). obtained from the determinate inverse dynamics problem, one can estimate the joint reactions in the supporting leg. To achieve this an effective method described in [3–5] can be applied. In this method, the previously used relationship p=g(q) is augmented to the form p=g(q,z″), where z″ are the open-constraint coordinates that describe the prohibited relative motions in the supporting leg joints, z″=[z 1 … z 6]T, which are the X and Y relative translations in the leg joints, illustrated in Fig. 2 for the right leg. From the augmented relationship one can obtain an n×l″ (42 × 6) matrix E″=(∂g/∂z″)z″ = 0, which is constant (and simple) for the case at hand. An important feature of the matrix is that , where 0 is the l″×l′ (6 × 20) null matrix and I″ is the l″×l″ (6 × 6) identity matrix. As explained in detail in [3–5], using E″ one can effectively determine the joint reaction forces in the supporting leg joints, i.e.

| 6 |

FIG. 2.

THE KINEMATIC CHAIN OF THE RIGHT LOWER LIMB, THE OPEN-CONSTRAINT COORDINATES AND THE RESPECTIVE REACTION FORCES IN THE LIMB JOINTS

The solution takes into account the ground reaction forces (during the contact phases), the contribution of the tensile muscle forces to the internal loads, and the dynamic interaction with the whole body motion.

Identification of the model

The anthropometric data used in the developed simulation model include the lengths of the segments, locations of their mass centres in the local coordinate frames, and their masses and central moments of inertia. The locations of the shoulder and hip joints in the local reference frames of segments 2 and 4, and the distance from the ankle joint A to point P, are also required (Fig. 1a). The segment lengths were directly measured from the subject, and the competitor mass was 70.1 kg. The segment masses, locations of their mass centres and the central moments of inertia were then estimated using the regression equations reported in [17, 18, 22], which were concerned with a series of additional measurements of characteristic lengths and sizes of the subject body. The lower limb musculoskeletal model required in addition the cross-sectional areas of the modelled muscles, and then the origin and insertion point locations in the local reference frames of appropriate segments. Of special importance was identification of the muscle paths relative to the skeleton [9, 21]. This involves, in particular, estimation of the muscle force arms with respect to appropriate joints [4].

Kinematic data

With the consent of the subject taking part in the experiment, the triple jump performance was recorded using a set of synchronized digital cameras (100 Hz), and the X and Y coordinates of a set of p = 19 base points on the athlete's body were digitized from the photographic images. The base points were marked on the jumper's skin so as to coincide with k = 13 model joints, and p – k = 6 additional base points were defined at the external segment tips, seen as black dots in Fig. 1a. With the coordinates of the base points, rj=[x j y j]T and , the position of each segment in the sagittal plane was defined by two appropriate base points. Then, for the ith segment, using the coordinates of its two assigned base points and the segment anthropometric data, the segment absolute coordinates p i =[x C y C θ i]T were determined. Repeating this for all the segments, the transformation r(t)→p(t) can effectively be achieved. The raw kinematic data were then smoothed to p d(t) using the second order Butterworth filter [15] with the cut-off frequency 10 Hz. The required characteristics were finally computed from p d(t), sampled with fixed time intervals Δt = 0.01s.

The acceleration at the kth sample was found numerically as

| 7 |

Simulation results

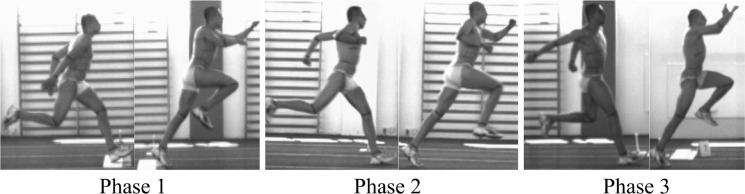

The analysis was limited to three landing and take-off phases, together with some short flying periods before and after the contacts with the runway (the contact phases were chosen for the expected high external reaction forces, reflected in the internal loads of the lower limbs). More strictly, Phase 1 starts after the approach run, just before the jumper touches the take-off board with the takeoff leg, covers the whole subsequent contact, and, after the take-off for the hop, includes a short period of the hop flight. Likewise, Phase 2 corresponds to the transition from the hop to the step (from the first to the second jump), and Phase 3 relates the transition from the step to the final jump. All the three phases are illustrated in Fig. 3, and the inverse dynamics simulation results can be seen in Fig. 4.

FIG. 3.

THE THREE CONTACT PHASES OF THE TRIPLE JUMP

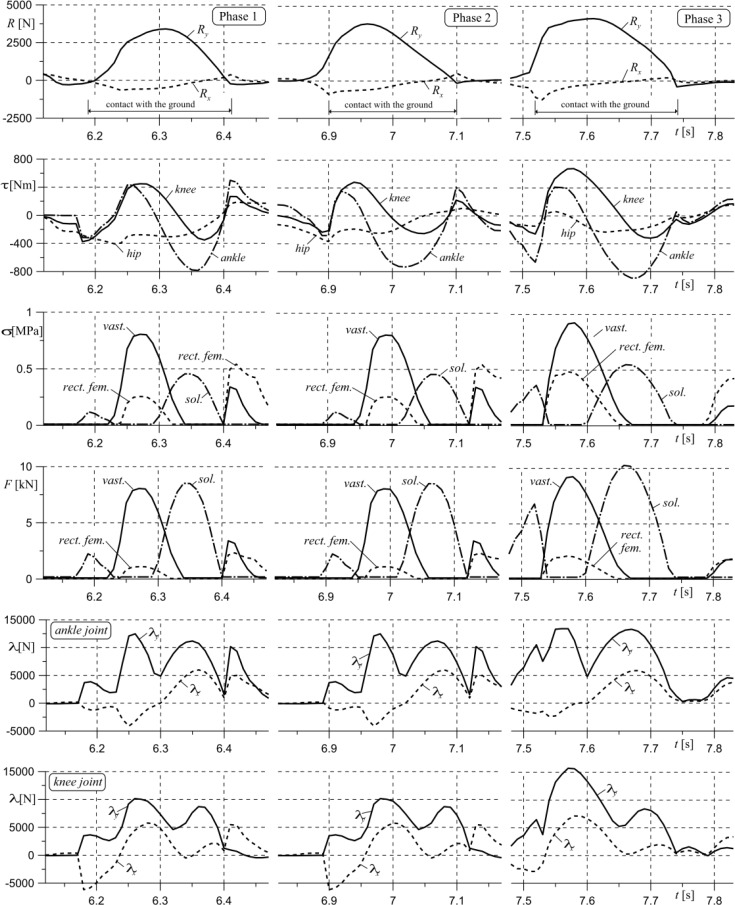

FIG. 4.

RESULTS OF INVERSE DYNAMICS SIMULATION OF THE THREE TAKE-OFF ACTIONS

DISCUSSION

As seen from the first-row graphs in Fig. 4, the assessed maximal vertical reactions R y from the ground are somewhere in the middle of the contact phases, and are equal to 3403 N, 3815 N and 4171 N, respectively for phase 1, 2 and 3. The maximal resultant ground reactions, , are respectively 3437 N, 3861 N and 4177 N, which are, respectively, 5.0, 5.6 and 6.1 times the body weight (G = 687 N) of the jumper. The maximal horizontal ground reactions were found just after landing during the second and third take-off actions, respectively 910 N and 1258 N (1.3 and 1.8 times body weight). The peak values and time histories of the ground reaction force components are similar to those obtained in [7], where a moderate long jump was analysed. On the other hand, the peak values of ground reactions during the triple jump reported in [13] are much bigger, ca. 15 and 3 times body weight respectively for the vertical and horizontal components in the braking portion of the step contact phase in the jump (here Phase 3). These were, however, the values measured from the force platform, and the values related to the impact forces (not represented in our calculations due to the smoothed kinematic data). Moreover, the triple jump distances reported in [13] were more than 14 m, while the distance analysed in this paper was approximately 12.5 m. There were also differences in the values of contact times. Respectively for the hop, step and jump, the contact times reported in [13] were 0.139 s, 0.157 s and 0.177 s, while in our study these were ca. 0.22 s, 0.20 s, 0.22 s. The performance of the triple jump reported in this paper was thus much less dynamic.

The second-row graphs in Fig. 4 show the variations of resultant muscular torques in the hip, knee and ankle joints in the left (phases 1 and 2) and right (phase 3) lower limbs. The torque values vary especially intensively in the beginning and final stages of the contacts with the ground. Again, the time characteristics of the net torques are similar to those obtained in [7] for a moderate long jump.

The next two rows of graphs illustrate the assessed stresses and forces of three selected muscles in the lower limbs: rect. fem. (rectus femoris), vast. (vastus) and sol. (soleus), denoted, respectively, as muscles m1, m2 and m5 in Fig. 1b. As can be seen, the vastus is active mainly during the landing stages, while the soleus is responsible for the take-offs. Certainly the estimated values of the optimal muscle stresses/forces are highly approximate. The values are strongly dependent on the modelling assumptions and the biomechanical parameters used in the computations. Moreover, before landings antagonistic muscles at the joints are usually activated in order to adjust stiffness of the muscle-tendon complex [19], which significantly increases the muscle forces and joint reaction forces. These phenomena are not included in the present model.

The final two rows show variations of the X and Y components of the ankle and knee reactions. The maximal estimated joint reaction is that in the knee joint during the landing after the step; the magnitude is more than 25 times the body weight of the jumper, and three times higher than the maximal ground reaction. This increase in the internal loads, compared with the external loadings, is due to the contribution of tensile muscle forces in the joints. For comparison, in [10] the reported maximum internal contact force in the knee during running reached the level of 40 and 17 times body weight, depending on whether the knee joint was modelled as a 3-DOF (degrees of freedom) or 1-DOF hinge joint. It is also worth mentioning that the resultant contact force in the knee joint is distributed between two femur epicondyles.

CONCLUSIONS

The human motion apparatus is extremely complex and, as such, very difficult to model. For these reasons the models used in the inverse dynamics analyses always involve simplifications and inaccuracies. In the literature (see e.g. [8] for a review) advanced analyses exist which incorporate the quantification of muscle force sensitivity with diverse modelling parameters. Some critical model parameters are associated with the assumptions related to the musculotendon paths and the effective attachment points of the tendons [4, 9, 21]. The physiological cross-sectional area of muscles is the other parameter that significantly affects the magnitude of muscle force estimates. Also of importance is the way the raw kinematic data are processed before they are used in the inverse dynamics simulation [17]. Finally, the muscle force estimates are influenced by muscle decomposition and recruitment criteria used in the force sharing optimization process [4]. Nonetheless, though the inverse dynamics simulation is always burdened with possible large inaccuracy, it remains the only available non-invasive method for assessment of the internal loads during human movements.

The reported evaluations show that, while the external (ground) reactions in the triple jump can be considered as moderate, the internal loads in the lower limbs may be extremely high. This situation is reflected in frequent injuries of locomotion apparatus structures, and different diseases after longer sport activity [1, 11, 13]. Knowledge of the muscle forces and joint reactions during the triple jump can be of great importance for risk assessment. More reliable assessment of the external and internal loads needs further improvements of the proposed simulation model. The filming frequency of 100 Hz should also be increased to register the contact phase effects with improved accuracy.

Acknowledgements

The work was financed in part from the government support of scientific research for years 2010-2012, under grant No. N N501 156438.

Conflict of interest

none declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen S.J. Loughborough, UK: Loughborough University; 2009. Optimization and performance in the triple jump using computer simulation. PhD Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen S.J, King M.A, Yeadon M.R. Is a single or double arm technique more advantageous in triple jumping? J. Biomech. 2010;43:3156–3161. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blajer W, Czaplicki A. An alternative scheme for determination of joint reaction forces in human multibody models. J. Theor. Appl. Mech. 2006;43:813–824. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blajer W, Czaplicki A, Dziewiecki K, Mazur Z. Influence of selected modeling and computational issues on muscle force estimates. Multibody Syst. Dyn. 2010;24:473–492. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blajer W, Dziewiecki K, Mazur Z. Multibody modeling of human body for the inverse dynamics analysis of sagittal plane movements. Multibody Syst. Dyn. 2007;18:217–232. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crowninshield R.D, Brand R.A. A physiologically based criterion of muscle force prediction in locomotion. J. Biomech. 1981;14:793–801. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(81)90035-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Czaplicki A, Silva M, Ambrósio J, Jesus O, Abrantes J. Estimation of the muscle force distribution in ballistic motion based on a multibody methodology. Comput. Meth. Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 2006;9:45–54. doi: 10.1080/10255840600603625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erdemir A, McLean S, Herzog W, van den Bogert A. Model-based estimation of muscle forces exerted during movements. Clin. Biomech. 2007;22:131–154. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garner B.A, Pandy M.G. The obstacleset method for representing muscle paths in musculoskeletal models. Comp. Meth. Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 2000;3:1–30. doi: 10.1080/10255840008915251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glitsch U, Baumann W. The three-dimensional determination of internal loads in the lower extremity. J. Biomech. 1997;30:1123–1131. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(97)00089-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hay J.G. The biomechanics of the triple jump: a review. J. Sport Sci. 1992;10:343–378. doi: 10.1080/02640419208729933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hay J.G. Effort distribution and performance of Olympic triple jumpers. J. Appl. Biomech. 1999;15:36–51. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perttunen J, Kyrolainen H, Komi P.V, Heinonen A. Biomechanical loading in the triple jump. J. Sport Sci. 2000;18:363–370. doi: 10.1080/026404100402421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robertson D.G.E, Caldwell G.E, Hamill J, Kamen G, Whittlesey S.N. Research Methods in Biomechanics. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seireg A, Arvikar R. Biomechanical Analysis of the Musculoskeletal Structure for Medicine and Sports. New York: Hemisphere Publishing Corporation; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Song J.-H, Ryu J.-K. Biomechanical analysis of the techniques and phase ratios of domestic elite triple jumpers. Int. J. Appl. Sports Sci. 2011;23:487–504. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Winter D.A. Biomechanics and Motor Control of Human Movement. 3rd Ed. Hoboken, Wiley, New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamaguchi G.T. Dynamic Modeling of Musculosceletal Motion. A Vectorized Approach for Biomechanical Analysis in Three Dimensions. Norwell, Kluwer, Massachusetts: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yeadon M.R, King M.A, Forrester S.E, Caldwell G.E, Pain M.T.G. The need for muscle co-contraction prior to a landing. J. Biomech. 2010;43:364–369. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.06.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu B, Hay J.G. Optimum phase ratio in the triple jump. J. Biomech. 1996;29:1283–1289. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(96)00048-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zajac F.E, Winters J.M. Modeling musculoskeletal movement systems: joint and body segmental dynamics, musculoskeletal actuation, and neuromuscular control. In: Winters J.M, Woo S.L.-Y, editors. Multiple Muscle Systems: Biomechanics and Movement Organizations. Berlin: Springer; 1990. pp. 121–148. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zatsiorsky V.M. Kinetics of Human Motion. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2002. [Google Scholar]