Abstract

Static stretch is a safe and feasible method which usually is used before exercise to avoid muscle injury and to improve muscle performance. The purpose of this study was to determine the effects of cyclic static stretch (CSS) on fatigue recovery of triceps surae (TS) in female basketball players. Nine athlete volunteers between 20 and 30 years participated in this study containing two sessions. After warm-up a pressure cuff was fastened above the knee joint and its pressure was increased to 140 mmHg. The subjects were asked to perform one maximum voluntary contraction (MVC) followed by a fatigue test including maximum isometric fatiguing contraction of TS. These steps were similar in both sessions. Then, a two-minute rest was included in the first session while 4 static stretches were performed to TS in the second session. After interventions, one MVC was done and the pressure cuff was released. During these steps, peak torque (PT) and electromyography (EMG) were recorded. The amount of lower leg pain was determined by the visual analogue scale (VAS). The value of PT increased significantly after CSS but its increase was not significant after rest. It seems that the effects of rest and CSS on the EMG parameters, PT and pain are similar.

Keywords: static stretch, fatigue recovery, triceps surae, basketball player, EMG, peak torque

INTRODUCTION

Fast muscle recovery is necessary for better muscle performance in sports with short inter-bout rest periods [14]. Static stretch is usually used before sport activities and it is believed that pre-exercise stretch will increase flexibility and reduce the risk of injury [3, 8]. A traditional warm-up regimen containing aerobic exercise and static stretch is used by athletes [9].

Blood flow improvement and fast muscle recovery are achieved by different modes of muscle relaxation that can help fast removal of metabolites. While it is obvious that rest is beneficial for muscle relaxation [14], some studies have reported the effects of stretch on the maximal strength, force production, muscular endurance and isokinetic PT [5, 7, 8]. Evidence suggests that pre-exercise stretch may compromise muscle ability to produce maximal force [8]. Some studies have reported that stretch may decrease muscle performance [7, 8], while others have reported no changes or even increase in strength capacity after stretching [8, 18]. After muscular fatigue there are some changes in electromyographic parameters. The purpose of this study was to examine the effects of stretch on median frequency (MDF), root mean square (RMS), and muscle PT after muscle fatigue, and compare the acute effects of CSS and rest on the fatigue recovery of TS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Nine female basketball players (mean ± SD: age = 24.11 ± 3.55 years, weight 63.22 ± 10.23 kg, height 170.78 ±10, body mass index 21.64 ± 2.4) participated in this study. All subjects were healthy and right leg dominant without any neurological, orthopaedic or cardiovascular diseases. They were not in monthly cycle and not pregnant at the time of the tests. The subjects were asked to avoid any foods or drinks containing caffeine for at least two hours before the test. If there were any artefacts in EMG recordings or if the subjects were not able to continue the test because of cramp or severe pain, they were excluded from the study. Prior to participating in the study, the subjects were informed about the project and signed written informed consent and voluntarily participated in the study. The study was approved by the ethical committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

Experimental approach to the problem

In this study, the effects of CSS and rest on the fatigue recovery of the TS were determined by changes in EMG parameters and PT. In this regard, two different experiments were performed and subjects were visited in two sessions. A fatigue test was applied in each session. Following fatigue protocols, rest and CSS of TS were used as interventions in the first and second sessions, respectively. The experimental sessions were separated by a one-week interval. Our pilot study demonstrated that this interval was sufficient to prevent any influence of the first session intervention on the results of the second session.

Procedures

In the first session, the subjects were familiarized with the instruments and experimental procedures. Then the subjects lay in a supine position on the dynamometer bench with their right lower limbs in full extension and their feet were placed on the force acceptance plate at 15 degrees of ankle dorsiflexion. Two straps were fastened across the thoracic and pelvic areas to fix the body on the dynamometer bench. Then three MVCs of TS were performed by each subject by pressing the foot against the force acceptance plate as hard as possible for 10 seconds with a 20-second rest between them. During MVCs, verbal encouragement was included. If there was more than 5% variation between recorded MVCs, an additional trial was performed and the upper value was chosen as the subject's MVC. After the three MVCs, they had 15 minutes of rest followed by a warm-up with 10 series of plantar flexion and dorsiflexion at 20% of MVC with the speed of 210 degrees per second, with an interval of one minute of rest. After warm-up and two minutes of rest, a pressure cuff was applied and fastened 10 centimetres above the knee joint and its pressure was increased in order to reach fatigue in a short time. The pilot study demonstrated that pressure of 140 mmHg was the best tolerable occlusive pressure and the subjects did not experience any cramp or pain that would prohibit them from continuing the tests. Thus, duration of the fatiguing contraction test for all subjects was proved to be shorter. Then, the subjects performed one MVC before the fatigue test (MVCbf), followed by the fatigue test consisting of a sustained maximum isometric contraction of TS. The subjects were asked to maintain the maximum plantar flexion PT to exhaustion. The output of PT was displayed on a personal computer and used as visual feedback for subjects. The time of exhaustion was determined when the maximum plantar flexion torque dropped to 50% of PT and did not increase at least for four seconds. These steps were similar in both sessions. In the first session after the fatigue test, the subjects had two minutes rest in a neutral position of the ankle joint and then performed one MVC after rest (MVCar). In the final stage, the cuff pressure was released.

In the second session, CSS of TS was done while the subject's foot was in a neutral position on the force acceptance unit of the dynamometer.

To perform the CSS protocol, the lever arm of the instrument moved the subject's foot passively to 20 degrees of ankle dorsiflexion with the speed of 20 degrees per second. The foot was held in this position for 20 seconds. Static stretch was repeated four times with a 10-second interval between them. Any muscular activity or stretch reflex of TS while performing CSS was checked by EMG. Then the subject performed one MVC after cyclic static stretch (MVCas) and the pressure cuff was released.

Measurements

Peak torque

The isometric torque of TS was recorded by an isokinetic dynamometer (Biodex sys 3. Medical, Incshirly, New York). The values of PT of MVCbf, at the end of the fatigue test, and MVCs after interventions (MVCar and MVCas) were determined and normalized to the PT of each subject's MVC.

EMG

After skin preparation, three bipolar silver/silver electrodes (diameter of 1 cm, centre to centre distance of 1 cm) were placed in the direction of the three heads of TS according to SENIAM recommendations. The captured signals were passed through a differential amplifier (gain 1000, internal impedance > 1015 Ohms, CMRR > 96 dB, bandwidth 20-450 Hz) (SX 230, Biometrics Ltd, UK). The reference electrode was placed on the ankle.

The values of RMS and median frequency (MDF) in the middle three seconds of MVCbf, MVCar and MVCas were measured. Also RMS and MDF of 500 ms during the fatiguing contraction just before reaching 50% of PT were calculated (RMS of the end of the fatigue test [RMSef] and MDF of the end of the fatigue test [MDFef]).

Pain

The amount of lower leg pain was determined by using a 100 mm visual analogue scale (VAS) before and after the fatigue test and after rest/CSS.

Statistical analyses

Two separate two-way repeated measures ANOVAs (time×muscle) were used to analyse the data of RMS and MDF. Two separate oneway ANOVAs with repeated measures of time were used to determine changes of pain and PT. When appropriate, Bonferroni was used for post-hoc comparison. Paired sample t-test was used to compare between the effects of rest and CSS.

RESULTS

Duration of the fatigue test

The mean duration of the fatigue test in the first session was 223.11 ± 84.56 seconds, while the fatigue test duration in the second session was 220 ± 77.09 seconds.

Pain

The subjects did not have any pain in their calf muscles before performing the fatigue tests. Repeated measure ANOVA demonstrated a significant main effect of time in the first session (F (2, 7) = 58.37, P = 0.0001). Post hoc analysis showed that at the end of the fatigue test compared to before the fatigue test, the amount of pain increased significantly to 7.06 ± 1.84 (P = 0.0001). However, after rest compared to the end of the test pain decreased significantly to 2.24 ± 1.39 (P = 0.0001). In the second session, there was a significant main effect of time (F (2, 7) = 43.7, P = 0.0001). At the end of the fatigue test, pain increased significantly compared to before the test (6.67 ± 2.10) (p = 0.0001). However, after CSS, the amount of pain decreased significantly to 2.37 ± 1.84 (P = 0.004) after CSS.

EMG parameters

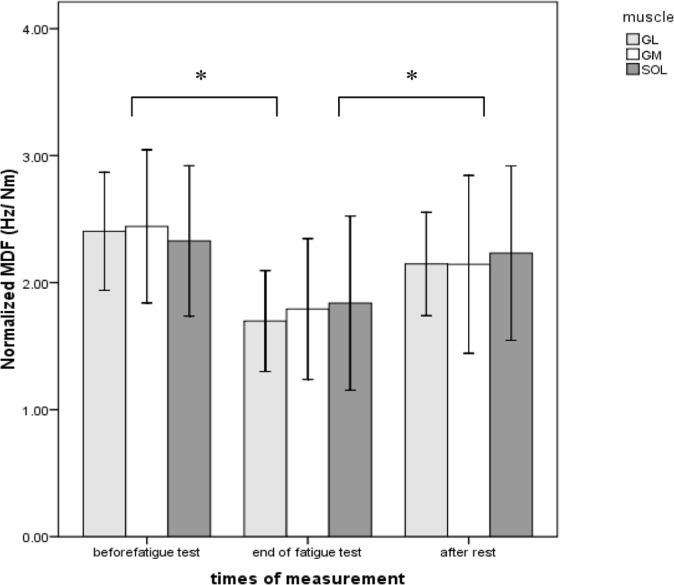

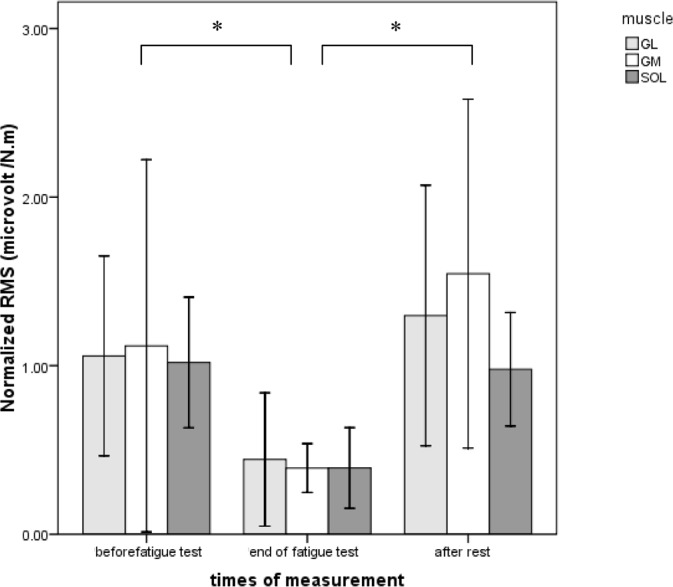

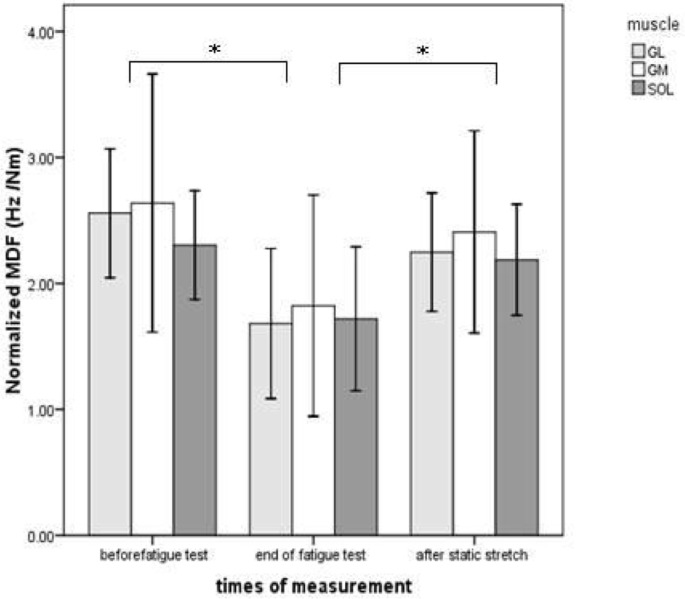

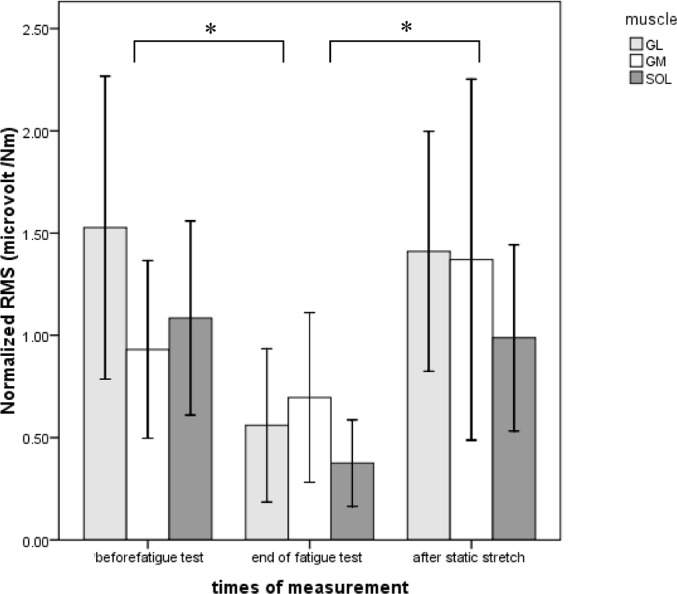

Analyses of data in the first session indicated neither a significant two-way interaction (time × muscle) nor a significant main effect of muscle; however, there was a significant main effect of time for MDF (F (2, 7) =28.2, P = 0.001) and RMS (F (2, 6) =15.11, P = 0.003). Post hoc analysis showed that in the first session at the end of the fatigue test there were significant decreases of MDF (P = 0.001) and RMS (P = 0.03) compared to before the test. In comparison with MDFef and RMSef, the values of MDFar and RMSar increased significantly (P = 0.001 and P = 0.002, respectively) (Figures 1, 2). Table 1 shows the mean values for MDF and RMS of the three heads of TS in the first session. In the second session the main effect of muscle and the interaction between time and muscle were statistically insignificant, but a significant main effect of time for MDF and RMS (F (2, 7) = 22.88, P = 0.001 and F (2, 7) = 16.22, P= 0.002, respectively), was observed. Post hoc analyses showed that the values of MDFef and RMSef compared with MDFbf and RMSbf decreased significantly (P = 0.0001 and P = 0.008, respectively). However, compared to MDFef and RMSef, the values of MDFas and RMSas increased significantly (P = 0.01 and P = 0.001, respectively) (Figures 3, 4). Table 2 shows the mean values of MDF and RMS of the three heads of TS in the second session.

FIG. 1.

NORMALIZED MDF BEFORE FATIGUE, AT THE END OF THE FATIGUE TEST AND AFTER REST

Note: The error bars represent mean ±1 SD, significant difference (P < 0.05)

FIG. 2.

NORMALIZED RMS BEFORE FATIGUE, AT THE END OF THE FATIGUE TEST AND AFTER REST

Note: The error bars represent mean ±1 SD., *significant difference (P < 0.05)

TABLE 1.

PURE VALUES OF MDF (HZ) AND RMS (V) (MEAN±SD) OF THE THREE HEADS OF TS BEFORE FATIGUE, AT THE END OF FATIGUE AND AFTER REST

| Muscle | Variable | Before fatigue | End of fatigue | After rest |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastrocnemius lateralis | MDF (Hz) | 128.6 ± 26.1 | 90.54 ± 21.28 | 116.02 ± 28.47 |

| RMS (v) | 54.5 ± 28.17 | 21.25 ± 14.71 | 66.58 ± 35.18 | |

| Gastrocnemius medialis | MDF (Hz) | 130.14 ± 37.80 | 92.53 ± 24.28 | 113.7 ± 30.38 |

| RMS (v) | 51.75 ± 44.01 | 22.03 ± 9.09 | 79.64 ± 48.53 | |

| Soleus | MDF (Hz) | 122.13 ± 18.97 | 96.93 ± 33.25 | 117.63 ± 28.31 |

| RMS (v) | 53.42 ± 19.46 | 20 ± 9.28 | 51.08 ± 14.9 |

Note: MDF - median frequency, RMS - root mean square

FIG. 3.

NORMALIZED MDF BEFORE FATIGUE, AT THE END OF THE FATIGUE TEST AND AFTER STATIC STRETCH

Note: The error bars represent mean ±1 SD., *significant difference (P < 0.05)

FIG. 4.

NORMALIZED RMS BEFORE FATIGUE, AT THE END OF THE FATIGUE TEST AND AFTER STATIC STRETCH

Note: The error bars represent mean ±1 SD., *significant difference (P < 0.05)

TABLE 2.

PURE VALUES OF MDF (HZ) AND RMS (V) (MEAN±SD) OF THE THREE HEADS OF TS BEFORE FATIGUE, AT THE END OF FATIGUE AND AFTER STRETCH

| Muscle | Variable | Before fatigue | End of fatigue | After rest |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastrocnemius lateralis | MDF (Hz) | 128.6 ± 26.1 | 90.54 ± 21.28 | 116.02 ± 28.47 |

| RMS (v) | 54.5 ± 28.17 | 21.25 ± 14.71 | 66.58 ± 35.18 | |

| Gastrocnemius medialis | MDF (Hz) | 130.14 ± 37.80 | 92.53 ± 24.28 | 113.7 ± 30.38 |

| RMS (v) | 51.75 ± 44.01 | 22.03 ± 9.09 | 79.64 ± 48.53 | |

| Soleus | MDF (Hz) | 122.13 ± 18.97 | 96.93 ± 33.25 | 117.63 ± 28.31 |

| RMS (v) | 53.42 ± 19.46 | 20 ± 9.28 | 51.08 ± 14.9 |

Note: MDF - median frequency, RMS - root mean square

Peak torque

Peak torque analyses demonstrated a significant main effect of time in the first and second session (F (2, 7) =10.88, P = 0.003 and F (2, 6) =63.29, P = 0.0001, respectively). Post hoc analyses showed significant decreases of PT (P =0.003 and P = 0.0001, respectively) at the end of the tests compared to before the tests. Before the test in the first and second sessions the values of PT were 52.03 ± 13.38 Nm and 53.51 ± 9.01 Nm, while at the end of the tests these values decreased to 34.46 ± 6.63 Nm and 37.92 ± 5.63 Nm, respectively. After rest an insignificant increase of PT (44.66 ± 9.53 Nm) (P = 0.08) occurred compared with the end of the fatigue test. However, after stretch compared to the end of the test, PT increased significantly (P = 0.01) to 47.78 ± 7.55 Nm.

Paired sample t-test did not show any significant differences between the effects of two interventions (rest/CSS) on PT.

DISCUSSION

According to the results of the study, in both sessions, maximum isometric fatiguing contraction of TS resulted in MDF decrease at the end of the fatigue test compared with before the test. Also, RMS decreases at the end of the fatigue test as compared with pre-test were significant in the first and second sessions. Based on previous studies, shift of the EMG power spectrum toward lower frequencies in sustained isometric contraction is an indication of muscle fatigue [14, 17, 20] and it is related to peripheral fatigue 13], insufficient muscle blood supply [15], pain [7, 17] and decrease of muscle fibre conduction velocity [13]. Moreover, pain receptor feedback may contribute to decrease of central drive [7]. In different studies changes of RMS were reported as increased, unchanged and decreased after fatiguing exercise [4]. Karabulut et al. [10] reported a significant decrease of EMG amplitude following fatiguing dynamic contraction of the vastus lateralis with vasorestriction (VR) compared with the condition without VR. They suggested that neuromuscular fatigue in the condition of VR may be due to a combination of peripheral and central fatigue, and decrease of EMG amplitude is an indication of inhibition of central drive to motor units [10]. In our study, the blood supply of the lower limb was restricted. This local ischaemia might cause disruption of the muscle excitation contraction cycle in muscular fatigue [22]. Some studies have reported an association between an increase in pain and a decrease in EMG activity of maximum contraction [7, 17]. Decrease of MDF and RMS in the present study showed a decrease of muscle activity level [5] and it might be due to both neural drive decrement and peripheral fatigue.

Changes of RMS and MDF after interventions

In both sessions, after interventions (rest/CSS) compared with the end of the fatigue test, significant increases of MDF and RMS occurred. This may be interpreted by the recruitment of new motor units (MUs) and increase of firing frequency of present active MUs. Meanwhile, the levels of these factors were still insignificantly lower than the levels at the time of pre-fatigue tests. Mika et al. [14] reported that after isometric contraction of the vastus lateralis, rest and PNF (proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation) stretch did not result in increase of MU activity. They suggested that rest duration of shorter than 10 minutes was not enough for complete fatigue recovery. Probably, duration of the interventions was not sufficient for a full increase of RMS and MDF in the present study. Restriction of circulation and pain may provide the condition of continuous stimulation of group III nerve fibres [22]. Decrease of pain after interventions may result in decrease of group III nerve fibre stimulation and proportional increase of MDF and RMS of TS. Furthermore, blood restriction may cause central fatigue which, in turn, results in decrease of both RMS and MDF. In addition, humans cannot fully activate the plantar flexors even in a non-fatigued state and it is enhanced during fatigue [11]. These factors may also explain the incomplete increase of RMS and MDF after interventions.

Peak torque

Peak torque decreased significantly in the first and second sessions after fatigue tests (27.4% and 31.8% respectively). However, its increment after rest (24.87%) was insignificant while it showed a significant increase after CSS (32.92%). Svantesson et al. [21] reported a 25% decrease of plantar flexor PT after concentric contraction and a 36% decrease after eccentric contraction. The percentage of decrease in PT in the present study is somewhat different from their results, probably due to the different types of contraction or individual differences between the subjects [1]. Decrease of PT of the gastrocnemius lateralis after concentric contraction was also reported by Larsson et al. [12].

Non contractile components such as series and parallel elastic components affect muscle PT as well as contractile components. Studies have reported different influences of stretching on muscle strength (decrease, establish or increase). Fowles et al. [7] after using 13 sets of stretching exercise, each lasting for 135 seconds, found a reduction of plantar flexor force. Franco et al. [8] reported that a high volume of static stretch resulted in more reduction of muscle strength and suggested that muscle performance reduction was dependent on the stretching protocol [8]. Egan et al. [5] reported that static stretch of knee extensors in women basketball players did not decrease muscle strength. Boscher [2] reported a significant decrease of hand grip strength after 3 bouts of static stretch each lasting 10 seconds. The difference between the results of those studies and the present study is probably related to different duration and intensity of stretch or different biomechanical characteristics of the studied muscles. Muscle flexibility improves individual tolerance to pain [6]. It is also possible that stretching decreases the internal muscular pressure and consequently improves muscle circulation and oxygen uptake [22]. These factors may be beneficial in increasing the PT after static stretch of TS.

CONCLUSIONS

The main finding of the present study is that CSS and rest are effective in increasing RMS and MDF of TS after fatigue in women basketball players

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from the Postgraduate Studies and Research Program, Tehran University of Medical Sciences. The authors would like to acknowledge the generous assistance of the staff and students of the Rehabilitation Faculty of Tehran University of Medical Sciences and the Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. We would like to acknowledge the professional basketball players who took part in this research and also the authors would like to thank the Farzan Institute for Research and Technology for technical assistance.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barry K.B, Enoka R.M. The neurology of muscle fatigue:15 years later. Symposim „Recent developments in neurobiology”; published online June 6, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boscher Torres J, Conceicao M.C.S.C, de Oliveria Sampaio A, Dantas E.H.M. Acute effects of static stretching on muscle strength. Biomed. Hum. Kinetics. 2009;1:52–55. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cramer T.J, Housh T.J, Weir J.P, Johnson G.O, Coburn J.W, Beck T.W. The acute effects of static stretching on peak torque, mean power output, electromyography, and mechanomyography. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2005;93:530–539. doi: 10.1007/s00421-004-1199-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dimitrova N.A, Dimitrov G.V. Interpretation of EMG changes with fatigue: facts, pitfalls, and fallacies. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2003;13:13–36. doi: 10.1016/s1050-6411(02)00083-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Egan A.D, Cramer J.T, Massy L.L, Marek S.M. Acute effect of static stretching on PT and mean power output in national collegiate athletic association division I women's basketball players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2006;20(4):778–782. doi: 10.1519/R-18575.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferreira G.N.T, Salmela T, Fuscaldi L, Queiroz G.C. Gains in flexibility related to measures of muscular performance: Impact of flexibility on muscular performance. Clin. J. Sports Med. 2007;17:276–281. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e3180f60b26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fowles J.R, Sale D.G, MacDougall J.D. Reduced strength after passive stretch of the human plantar flexors. J. Appl. Physiol. 2000;89:1179–1188. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.3.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franco B.L, Signorelli G.R, Trajano G.S, De Oliveira C.G. Acute affects of different stretching exercises on muscular endurance. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2008;22:1832–1837. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31818218e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gelen E. Acute effects of different warm-up methods on jump performance in children. Biol. Sport. 2011;28:133138. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karabulut M, Cramer J.T, Abe T, Sato Y, Bemben M.G. Neuromuscular fatigue following low-intencity dynamic exercise with externally applied vascular restriction. J Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2010;20:440–447. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kawakami Y, Amemia K, Kanehisa H, Ikegawa S, Fukunaga T. Fatigue responses of human TS muscles during repetitive maximal isometric contractions. J. Appl. Physiol. 2000;88:1969–1975. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.6.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larsson B, Kadi F, Lindvall B, Gerdle B. Surface electromyography and PT of repetitive maximum isokinetic plantar flexions in relation to aspects of muscle morphology. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2006;16:281–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maïsetti O, Guével A, Legros Hogrel J.-Y. SEMG power spectrum changes during a sustained 50% Maximum voluntary isometric torque do not depend upon the prior knowledge of the exercise duration. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2002;12:103–109. doi: 10.1016/s1050-6411(02)00010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mika A, Mika P, Fernhall B, Unnithan V.B. Comparison of recovery strategies on muscle performance after fatiguing exercise. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2007;86:474–481. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e31805b7c79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nordez A, Gue′vel A, Casari P, Catheline S, Cornu C. Assessment of muscle hardness changes induced by a submaximal fatiguing isometric contraction. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2009;19:484–491. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Osterberg U, Svantesson U, Takahashi H, Grimby G. Torque, work and EMG development in a heel-rise test. Clin. Biomech. 1998;13:344–350. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(98)00100-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ravier P, Buttelli O, Jennane R, Couratier P. An EMG fractal indicator having different sensitivities to changes in force and muscle fatigue during voluntary static muscle contractions. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2005;15:210–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schulte E, Ciubotariu A, Arendt-Nielsen L, Disselhorst-Klug C, Rau G, Graven-Nielsen T. Experimental muscle pain increases trapezius muscle activity during sustained isometric contractions of arm muscles. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2004;115:1767–1778. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shellock F.G, Prentice W.E. Warming –up and stretching for improved physical performance and prevention of sports-related injuries. Sports Med. 1985;2:267–278. doi: 10.2165/00007256-198502040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steele D.S, Duke A.M. Metabolic factors contributing to altered Ca2+ regulation in skeletal muscle fatigue. Acta Physiol. Scand. 2003;179:39–48. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2003.01169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Svantesson U, Österberg R, Thomeé Peeters M, Grimby G. Fatigue during eccentric – concentric and pure concentric muscle actions of the plantar flexors. Clin. Biomech. 1998;13:336–343. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(98)00099-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tiidus P.M. Manual massage and recovery of muscle function following exercise: A literature review. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 1997;25:107–112. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1997.25.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]