Recent case–control genome-wide association studies have linked common variants of TMEM132D (KIAA1944, MOLT) with panic disorder (PD), anxiety comorbidity in depression, and anxiety symptom severity in healthy and diseased subjects.1 One risk genotype (rs11060369 AA) is associated with enhanced TMEM132D mRNA expression in the brain; brain mRNA expression is also higher in mice bred for extreme anxiety-like behavior.1 The current study demonstrates enhanced amygdala gray matter volumetric estimates and an anxiety-related (but not panic-specific) personality profile in healthy normal carriers of the rs11060369 AA genotype. Our data suggest a role for TMEM132D in shaping threat processing.

TMEM132D is a transmembrane protein expressed in neurons and colocalized with actin filaments2 that putatively functions as a cell-surface marker for oligodendrocyte differentiation.3 The TMEM132D single-nucleotide polymorphisms related so far to PD in patients of European ancestry or to anxiety in general are intronic and presumably tag yet unknown intronic functional regulatory variants.1,4 Next to common variants, rare TMEM132D variants have also been linked with pathological anxiety.5

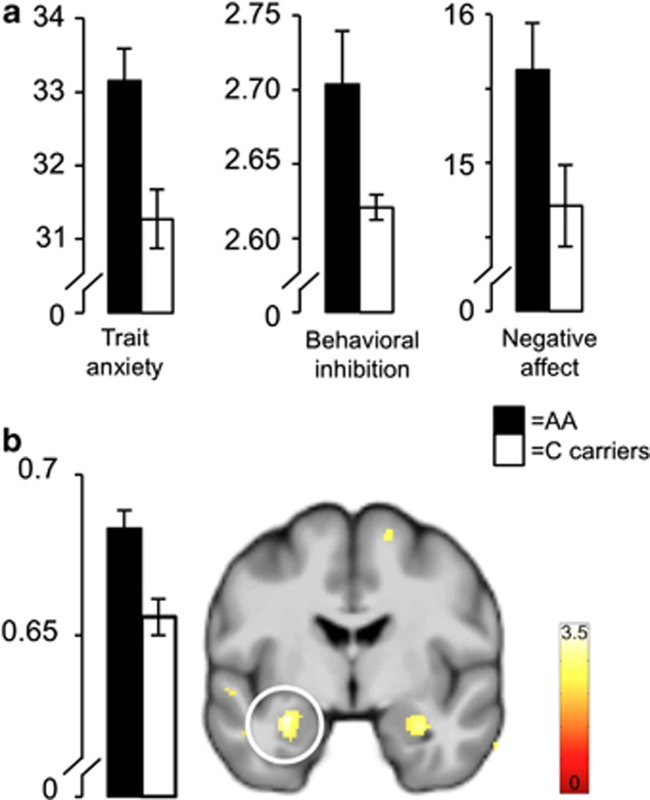

We interrogated an independent sample of 315 healthy normal subjects (99 female) of Caucasian descent, of which 132 (22 female) underwent structural magnetic resonance imaging, for TMEM132D genotype effects on personality and brain morphology (see Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Table 1 for details). The variant rs11060369 was the only one that showed a significant omnibus effect on a battery of anxiety-related personality questionnaires (F(8,32)=3.34, P=0.0008, η2=0.07). A homozygotes had higher scores than C carriers on general measures of trait anxiety (F(1,302)=12.72, P<0.001, η2=0.04), behavioral inhibition (F(1,302)=8.53, P=0.004, η2=0.03) and negative affect (F(1,302)=4.98, P=0.026, η2=0.02; Figure 1a), but not on more disease-specific measures like anxiety sensitivity, agoraphobic cognitive style, worrying, social anxiety or depression (all P-values>0.17; see Supplementary Table 2).

Figure 1.

Higher anxiety-related personality scores in rs11060369 A homozygotes (N=164) as compared to C carriers (N=151). (a) Higher gray matter volumetric estimates in rs11060369 A homozygotes (N=68) as compared to C carriers (N=65) in the left amygdala (bars show maximum at Montreal Neurological Institute coordinates x, y, z=−30, −6, −20) and, at trend level, right amygdala (30, −6, −20). (b) Color-coded effects are superimposed on average structural image. Color bar: t-scores. Display threshold: P(uncorrected)<0.01. Error bars: s.e.m.

rs11060369 A homozygotes also had higher gray matter volumetric estimates in the left amygdala (Z=3.39, P=0.014, small volume corrected for multiple comparisons (SVC); right side: Z=2.87, P(SVC)=0.089, trend; Figure 1b). Including trait anxiety, behavioral inhibition and negative affect scores into the volumetric analysis as covariates of no interest did not change the results (data not shown). An exploratory whole-brain analysis at an uncorrected threshold of P<0.001 additionally yielded higher estimates in A homozygotes in the left hippocampus extending into the amygdala and the cerebellum (Supplementary Table 3; reported descriptively only). There were no supra-threshold voxels in the inverse contrast.

In a further exploratory analysis of the other common TMEM132D risk variants, carriers of the T/A rs11060369/7309727 combination showed a strong trend for higher estimates in the left amygdala (Z=3.17, P(SVC)=0.026 and Z=3.15, P(SVC)=0.027) than carriers of the C/A and C/C combinations (Supplementary Table 3, Supplementary Figure 1). At an uncorrected threshold, differences were also observed in the hippocampus, the insula and the other regions (Supplementary Table 3). At the same exploratory threshold (P<0.001), we observed higher volumetric estimates in the right hippocampus and right caudate in T Carrier compared to C homozygotes in an additional common TMEM132D risk variant, rs7309727 (Supplementary Table 3). There were minor effects of variant rs7309727 and no effects of variants rs900256 and rs879560 (Supplementary Table 3).

rs11060369, rs7309727 and their combination have so far been more closely linked to a diagnosis of PD than to anxiety disorders in general or to non-disease-specific dimensional anxiety phenotypes.1,4 A correlation with dimensional anxiety measures for rs900256 and rs879560 and the cited mouse TMEM132D expression data, however, have been taken to support a more generic role for the protein in threat processing.1 Our observation in a sample of healthy normal volunteers of extended, genotype-dependent volumetric differences in a key neural structure associated with fear and anxiety6, 7, 8 can be interpreted as pointing toward a generic role in threat processing. This conclusion is further supported by our personality data. Our results therefore highlight TMEM132D as having an important molecular role in fear and anxiety.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG grants: KA1623/3-1, KA1623/4-1, SFB TRR58 Z02) and the State of Hamburg excellence initiative (neurodapt! consortium). We thank F Faβbinder for help with data acquisition and processing.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Translational Psychiatry website (http://www.nature.com/tp)

Supplementary Material

References

- Erhardt A, Czibere L, Roeske D, Lucae S, Unschuld PG, Ripke S, et al. Mol Psychiatry. 2011. pp. 647–663. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Walser SM, Dedic N, Touma C, Floss T, Wurst W, Holsboer F, et al. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2011.

- Nomoto H, Yonezawa T, Itoh K, Ono K, Yamamoto K, Oohashi T, et al. J Biochem. 2003. pp. 231–238. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Erhardt A, Akula N, Schumacher J, Czamara D, Karbalai N, Müller-Myhsok B, et al. Transl Psychiatry. 2012. p. e156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Quast C, Altmann A, Weber P, Arloth J, Bader D, Heck A, et al. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2012. pp. 896–907. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ono T, Nishijo H. Wiley-Liss: New York, NY, USA; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein JS, Adolphs R, Damasio A, Tranel D. Curr Biol. 2011. pp. 34–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Davis M, Whalen PJ. Mol Psychiatry. 2001. pp. 13–34. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.