New crystallization conditions for the catalytic domain of human ubiquitin specific protease 7 (USP7CD) were found that produced crystals in space group C2 with one molecule in the asymmetric unit which is an advantage over previous crystallization conditions of USP7CD which produced crystals in space group P21 with two molecules in the asymmetric unit. Comparison of the refined structure of USP7CD in space group C2 with that of P21 suggests that conformational rearrangement of blocking loop residues 410–419 must occur in order for ubiquitin to bind and that the catalytic triad and switching loop region are in the same catalytically unproductive conformations as in the P21 structure in the absence of ubiquitin.

Keywords: USP7, ubiquitin binding

Abstract

A sparse-matrix screen for new crystallization conditions for the USP7 catalytic domain (USP7CD) led to the identification of a condition in which crystals grow reproducibly in 24–48 h. Variation of the halide metal, growth temperature and seed-stock concentration resulted in a shift in space group from P21 with two molecules in the asymmetric unit to C2 with one molecule in the asymmetric unit. Representative structures from each space group were determined to 2.2 Å resolution and these structures support previous findings that the catalytic triad and switching loop are likely to be in unproductive conformations in the absence of ubiquitin (Ub). Importantly, the new structures reveal previously unobserved electron density for blocking loop 1 (BL1) residues 410–419. The new structures indicate a distinct rearrangement of the USP7 BL1 compared with its position in the presence of bound Ub.

1. Introduction

Post-translational addition of ubiquitin (Ub) or Ub-like proteins serves as a signal that can alter the fate of cellular proteins by prompting degradation, regulation or movement between subcellular locations. Ub is a 76-residue globular protein that is covalently coupled to the C-terminus of target-protein lysine residues by Ub ligases. Adding further Ub molecules to one of the seven lysine residues in the original Ub can create Ub chains with specific signaling purposes. The activity of Ub ligases is balanced by a family of more than 80 de-ubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) or ubiquitin-specific proteases (USPs) that catalyze the removal of Ub modifications of varying lengths and linkage types (Hershko & Ciechanover, 1998 ▶). Regulation of the balance between Ub-ligase and DUB activity is vital to cellular homeostasis and to the process of programmed cell death. Perturbation of this balance can lead to cancer owing to cells that lack adequate levels of tumor suppressor protein or are allowed to inappropriately exit cell-cycle checkpoints as a result of DUB overexpression or overactivity (Nicholson et al., 2007 ▶; Reyes-Turcu et al., 2009 ▶).

USP7, also known as herpes-associated ubiquitin-specific protease (HAUSP), exhibits extensive human tissue distribution as well as overexpression in prostate cancer (Song et al., 2008 ▶). It plays a role in regulation of the tumor suppressor protein p53 by removing Ub from the E3 ubiquitin ligase HDM2, which is responsible for ubiquitination of p53 (Li et al., 2004 ▶; Cummins et al., 2004 ▶). Additionally, USP7 is involved in herpesviral and adenoviral infection and replication (Everett et al., 1997 ▶). Despite the impressive scope of USP7 interactions and target pathways, only modest progress towards the development of small-molecule inhibitors of USP7 is evident, and currently no crystal structures of USP7 bound to a small-molecule inhibitor exist. Co-crystallization or soaking of enzymes with validated hits from high-throughput screening (HTS) can provide indispensable structural information that improves further rounds of inhibitor synthesis. The structures described herein represent our efforts to find a crystallization condition that yields robust reproducible crystals in a space group that is amenable to inhibitor soaking and to rapid structure solution by isomorphous molecular replacement.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Protein expression and purification

The nucleic acid sequence coding for the catalytic domain (208–560) of Ub-specific protease (USP7CD) with an N-terminal hexahistidine (His6) tag followed by a Tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease cleavage site was synthesized by BioBasic (codon-optimized for expression in Escherichia coli) and inserted into the expression vector pET-11a using NdeI and BamHI restriction sites. Recombinant protein was expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells by initial incubation in 1 l LB medium at 37°C with shaking until the cultures reached an optical density of 0.6. Expression of USP7CD was then induced with 0.25 mM (final concentration) isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) followed by incubation at 18°C with shaking overnight. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4000g at 4°C for 15 min. Lysis was performed by sonication on ice using a cycle of 10 s on, 5 s off at 65% amplitude for a total of 10 min. The lysate was then clarified by centrifugation at 13 000g at 4°C for 30 min. USP7CD was isolated from the clarified lysate using Ni–NTA chromatography on a 5 ml HisTrap column (GE Healthcare) as described previously (Wrigley et al., 2011 ▶). The His6 tag was removed by overnight incubation at 4°C with TEV protease at a 1:50 (TEV protease:USP7CD) ratio. The cleaved sample was concentrated to 5 mg ml−1 in a volume of 5 ml using a 10 000 Da molecular-weight cutoff concentrator (Millipore) and was then loaded onto a 300 ml Superdex 75 (GE Healthcare) size-exclusion chromatography column equilibrated with 20 mM Tris pH 7.6, 200 mM NaCl, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol (βME), 1 mM EDTA, 2%(v/v) glycerol for final purification. Peak fractions containing USP7CD, as visualized by SDS–PAGE and confirmed by Ub-AMC activity assays, were pooled and concentrated to a protein concentration of 24 mg ml−1. The final purified USP7CD was then either flash-frozen in SEC buffer and stored at −80°C or immediately dialyzed against 10 mM Tris pH 7.6, 10 mM NaCl, 10 mM βME for crystallization trials.

2.2. Crystallization

The Classics and Classics II Suites (Qiagen) sparse-matrix screens were set up in 96-well sitting-drop trays (Corning) at a USP7CD concentration of 24 mg ml−1 with drops consisting of 1 µl protein solution and 1 µl well solution and were incubated at 25°C. An initial hit of thin plate-like crystals was obtained at 25°C from The Classics II Suite condition No. 72 consisting of 0.15 M NaCl, 25% PEG 3350, 0.1 M HEPES pH 7.5. Optimization of this condition was initially achieved by substitution of NaBr and KCl for NaCl, variation of the PEG 3350 concentration over a range from 20 to 30% in 2% intervals and incubation at 12 and 20°C. The best crystals grew at 12°C in 0.2 M NaBr, 0.1 M HEPES pH 7.5, 22% PEG 3350 and were pursued by further optimization of this condition via supplementation with a 96-condition additive screen (Hampton Research) and microseeding. A microseed stock was made by harvesting the plates grown in a 4 µl drop of the original condition and was employed according to the methods outlined by Bergfors (2003 ▶). Diffraction-quality crystals formed in a variety of conditions from the second round of optimization at both temperatures. The crystals that produced the best diffraction appeared after 12 h at 12°C in buffer consisting of 0.2 M NaBr, 22% PEG 3350, 0.1 M HEPES pH 7.5, 0.15 mM CYMAL-7 and after addition of a 4.44 × 10−8 seed stock from the original condition. Crystals (mounted on 0.1–0.5 µm nylon loops) were cryoprotected by moving them sequentially through small drops containing well solution plus 5%, 10%, 15% and finally 20% glycerol. After the final soak, the crystals were mounted and then rapidly flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen.

2.3. Data collection and structure refinement

X-ray diffraction data were collected on LS-CAT beamline 21-ID-G of the Advanced Photon Source (APS) at Argonne National Laboratory, Argonne, Illinois, USA. For those crystals from which full data sets were not collected, their space groups were determined by indexing two or more frames. Full data sets were collected from other crystals and were indexed, integrated and scaled using HKL-2000 (Otwinowski & Minor, 1997 ▶). The resulting structure factors were used for molecular replacement (MR) using the molecular-replacement module of PHENIX (Adams et al., 2010 ▶) and the structure of the USP7CD apoenzyme (PDB entry 1nb8; Hu et al., 2002 ▶). The model was refined using PHENIX (Afonine et al., 2005 ▶), and manual inspection, rebuilding and addition of water molecules and ions were performed iteratively with Coot (Emsley et al., 2010 ▶) and PHENIX using the refine module. Data-collection and refinement statistics are given in Table 1 ▶.

Table 1. Data-collection and refinement statistics for USP7CD structures.

Values in parentheses are for the last shell.

| PDB entry | 4m5w | 4m5x |

|---|---|---|

| Data-collection parameters | ||

| Crystal conditions | Flash-cooled at 173C | |

| X-ray source/detector | 21-ID-G, APS/MAR Mosaic 300 | |

| Wavelength () | 0.976 | |

| Resolution limit () | 2.24 | 2.19 |

| Space group | C2 | P21 |

| Unit-cell parameters (, ) | a = 102.3, b = 69.2, c = 75.7, = 131.3 | a = 75.9, b = 67.6, c = 76.8, = 96.2 |

| Data-processing statistics | ||

| Data resolution range () | 502.24 (2.292.24) | 502.19 (2.242.19) |

| Reflections | ||

| Total No. recorded | 61729 | 130445 |

| No. unique | 17493 | 38925 |

| Completeness† (%) | 92.6 (66.4) | 98.5 (89.0) |

| Average multiplicity | 3.5 (2.8) | 3.4 (2.9) |

| R merge (%) | 7.7 (54.9) | 7.7 (50.8) |

| Average I/(I) | 19.9 (2.1) | 20.44 (1.9) |

| Refinement statistics | ||

| Data resolution range () | 38.42.24 (2.382.24) | 38.222.19 (2.142.19) |

| No. of reflections in working set | 17493 | 38888 |

| No. of reflections in test set | 899 | 1956 |

| R work ‡ (%) | 18.6 (26.55) | 18.0 (21.7) |

| R free § (%) | 24.2 (34.7) | 22.1 (26.3) |

| Figure of merit¶ | 0.7467 | 0.825 |

| R.m.s. deviations | ||

| Bond lengths () | 0.007 | 0.008 |

| Bond angles () | 1.11 | 1.16 |

| Dihedrals () | 15.8 | 15.7 |

| Ramachandran plot | ||

| Most favored (%) | 93.51 | 95.2 |

| Allowed (%) | 6.49 | 4.35 |

| Disallowed (%) | 0 | 0.45 |

| No. of protein molecules in final model | 1 | 2 |

| Wilson B factor (2) | 40.0 | 32.6 |

| Average B factor (2) | 61.2 | 41.3 |

| No. of ligand molecules in final model (Br) | 4 | 3 |

| No. of H2O molecules | 86 | 145 |

Completeness for I/(I) > 1.0.

R

work =

.

.

R free was calculated against 5% of the reflections removed at random.

Figure of merit =

, where is the phase and P() is the phase probability distribution.

, where is the phase and P() is the phase probability distribution.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Crystallization, structure determination and model quality

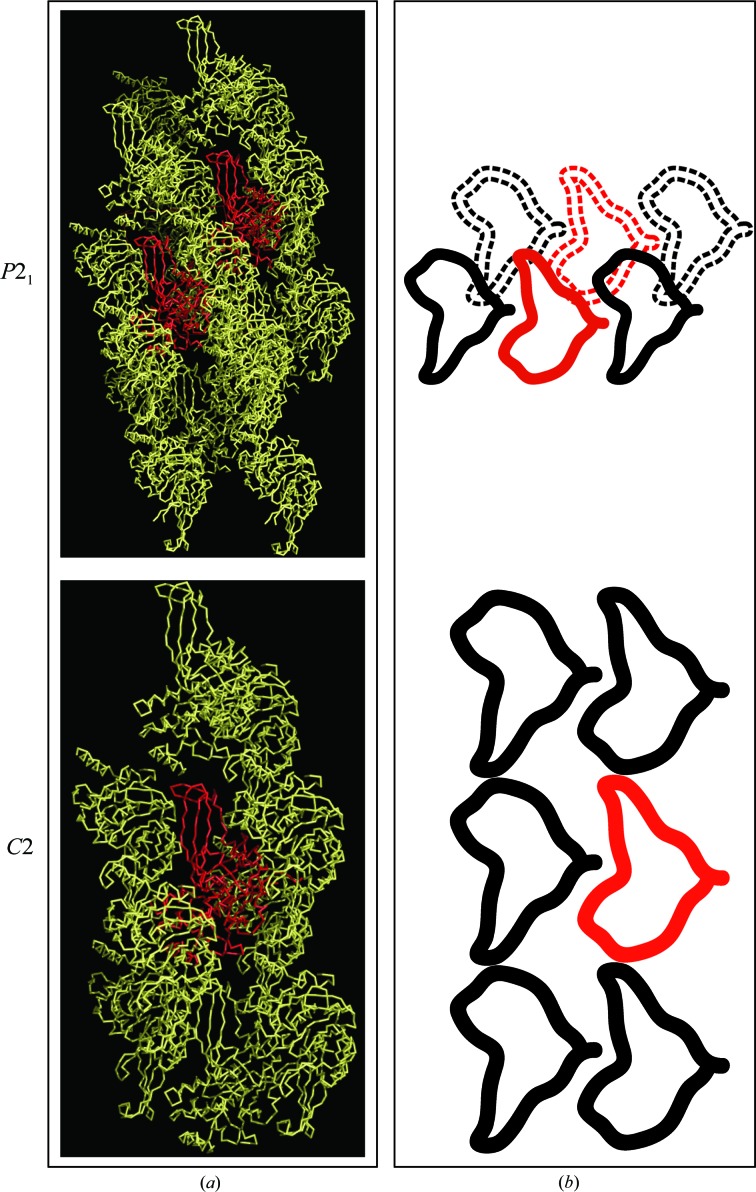

50 crystals were selected from the optimization screens at both 12 and 20°C for X-ray data collection. Of these crystals, 34 were found to belong to space group P21, with maximum resolution covering a range from 2.2 to 5.2 Å. Surprisingly, the remaining 16 crystals belonged to space group C2, with a maximum resolution range from 2.2 to 3.4 Å. Occasionally, crystals representing each space group were present in the same crystallization drop, as was the case for the crystals which generated the best data sets for each space group. The best representative structure from space group C2 (PDB entry 4m5w) was structurally aligned with chain A of the best P21 structure determined (PDB entry 4m5x) and the resulting all-atom r.m.s.d. value was 0.175 Å, suggesting that the two structures are essentially identical. Further analysis of the conditions that produced each space group revealed an interesting phenomenon with regard to the relationship between crystal-growth temperature and space group: 13 of the total of 16 C2 crystals (84%) grew at 12°C. This observation would at first suggest a significant difference in crystal growth between the two temperatures. However, analysis of the crystal packing in each space group indicates that no significant change in packing arrangement or solvent-channel dimensions occurs (Fig. 1 ▶ a). Instead, we propose that a temperature-related conformational change in one subunit breaks the C2 symmetry and leads to two molecules in the asymmetric unit (P21) instead of one (C2). It is worthwhile to note that the previously published USP7CD apoenzyme structure (PDB entry 1nb8; Hu et al., 2002 ▶) was also solved in space group P21 with very similar unit-cell parameters to those reported here for our P21 structure (PDB entry 4m5x). Since the C2 crystals have only one USP7CD molecule per asymmetric unit, compared with two molecules per asymmetric uni in the P21 crystals (Fig. 1 ▶ b), and the C2 crystals diffracted to higher resolution on average, conditions favoring space group C2 may be the best choice for future attempts at co-crystallization or soaking of USP7CD with inhibitors.

Figure 1.

USP7CD crystallizes in two space groups with similar but not identical packing arrangements. (a) Ribbon diagram showing symmetry mates within 4 Å of the asymmetric unit of USP7CD in space groups P21 (upper panel) and C2 (lower panel). (b) Schematic drawing of the packing arrangement for each space group, in the same orientation as in (a), where the USP7CD molecules shown in (a) are represented as an outline and the USP7CD molecules representing the asymmetric unit are shown in red (dashed lines represent an underlying row of molecules).

3.2. The blocking loop 1 (BL1) and catalytic triad are in a catalytically incompetent state in the USP7CD apoenzyme

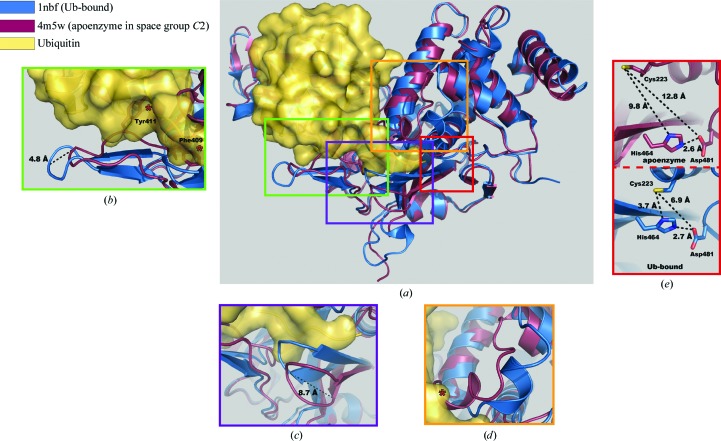

When these new structures in space groups C2 and P21 are aligned with the original USP7CD apoenzyme structure (Hu et al., 2002 ▶), the resulting all-atom r.m.s.d. values for the superposition are 0.26 and 0.28 Å, respectively. These r.m.s.d. values match within coordinate error, indicating significant similarities among the structures. Moreover, the residues composing the catalytic triad overlay without discernable deviation between the three structures. However, the r.m.s.d. values of the C2 and P21 structures reported here when aligned in the same manner with the Ub-bound structure of USP7CD (Hu et al., 2002 ▶) are 1.09 and 0.98 Å, respectively, suggesting conformational differences between the structures of the apo and Ub-bound forms (Fig. 2 ▶ a). A similar r.m.s.d. (0.77 Å) is observed upon comparison of the previous apoenzyme and Ub-bound structures of USP7CD.

Figure 2.

Structural rearrangements of USP7CD upon ubiquitin binding. (a) Alignment of PDB entries 1nbf (Hu et al., 2002 ▶; USP7CD in blue, ubiquitin in yellow) and 4m5w (maroon). (b) Blocking loop 1 (BL1) is visible in the new apoenzyme structure (shown here in space group C2). Residues Phe409 and Tyr411, which clash with Ub in the apoenzyme structure, are marked with red asterisks. To accommodate Ub, the BL1 loop must shift away from the Ub site to remove any steric hindrance. (c) Blocking loop 2 (BL2) rearranges via an 8.7 Å shift to stabilize the Ub C-terminus upon Ub binding. (d) The switching loop (residues 285–291) clashes with Ub (red asterisk) in the apoenzyme conformation but undergoes translation and rotation in the presence of Ub. (e) Ub binding prompts reorientation of active-site residues from a nonproductive conformation (top) to a classic triad formation (bottom). The measurements in each panel indicate the distances between residues of the catalytic triad.

Importantly, our new structures reveal density for the backbone of a loop region that was not visible in the previous USP7CD apoenzyme structure. These residues (410–419) form the majority of blocking loop 1 (BL1; Fig. 2 ▶ b). Density for BL1 is observable in the single molecule of the C2 asymmetric unit (PDB entry 4m5w), as well as in chain A (but not chain B) of the P21 asymmetric unit (PDB entry 4m5x). For clarity, the C2 structure (PDB entry 4m5w) is used from this point forward for purposes of visual comparison; however, comments pertaining to USP7 BL1 positioning refer to the BL1 loops visible in both new structures.

Crystal structures of other USP catalytic domains suggest the presence of two surface loops, BL1 (408–429) and BL2 (459–462), that obscure the binding pocket for the C-terminus of Ub in the apoenzyme. While there are examples of observable density for the BL1 and BL2 positions in either Ub-bound or apoenzyme forms of USPs, USP14 (Hu et al., 2005 ▶) and USP8 (Ernst et al., 2013 ▶; Avvakumov et al., 2006 ▶) were the only cases in which structures had been solved in both apoenzyme and bound forms. It was previously concluded that the absence of residues 410–419 in the USP7CD apoenzyme structure indicated that BL1 does not disrupt Ub binding in USP7 (Hu et al., 2005 ▶). Our structural data clearly show, however, that in the absence of Ub the BL1 backbone is fully capable of blocking the Ub binding site. An approximately 3.3 Å shift of the BL1 loop away from the Ub site has to occur in order for the apoenzyme to accommodate the binding of Ub (Fig. 2 ▶ c). Although flexibility suggests movement of BL1, our structure reveals a small but distinct conformational change upon Ub binding in every instance in which BL1 is observable. Additionally, the USP7 BL1 loop seems to become more ordered in the presence of Ub in a manner similar to that observed for the structures for USP2, USP8 and USP14 based on the change in B factors calculated for the loop in the presence and absence of Ub (Supplementary Fig. S1a 1). Further support for increased stability stems from the observation that the amino acids within the loop adopt more β-sheet character in the Ub-bound structures compared with the apoenzyme structures (Renatus et al., 2006 ▶; Hu et al., 2005 ▶; Ernst et al., 2013 ▶). Despite the elevated B factors of this loop, there is continuous observable density for the peptide backbone in both 2F o − F c and OMIT maps for the residues that would interfere with Ub binding (Supplementary Fig. S2). BL2 also repositions by approximately 8.7 Å upon Ub binding, possibly to stabilize the Ub C-terminal region in the catalytic channel (Fig. 2 ▶ c). When analyzed along with the BL1 and BL2 loop positions observed in other USP structures, our structure strongly suggests that movement of these loops is a prerequisite for Ub binding and subsequent catalysis in all USPs in which they are present.

The new structures of USP7 further support the observation that residues 285–291, referred to as the ‘switching loop’ (Faesen et al., 2011 ▶), seem to rearrange upon Ub binding (Fig. 2 ▶ d). Although not highlighted previously (Hu et al., 2002 ▶), the importance of this region, which is proximal to the helix containing the active-site catalytic cysteine Cys223, is now brought into focus by the observation that this loop seems to interact with the ‘activation peptide’ composed of the most C-terminal residues of USP7 (residues 1058–1077; Faesen et al., 2011 ▶). We observed a rotation and translation of the switching loop compared with the Ub-bound structure, as in the earlier work. B-factor analysis of this loop indicates that its positioning in the apoenzyme may be somewhat more rigid than in the Ub-bound form (Supplementary Fig. 1 ▶ b). This observation suggests that external forces, such as interaction with the activating peptide, may be required to reposition the switching loop to prevent clashes with Ub and for rearrangement of the catalytic triad.

As in the original USP7CD apoenzyme structure, the catalytic triad in the C2 and P21 structures is clearly in a noncatalytic conformation, with the catalytic cysteine (Cys223) 10.6 and 9.6 Å away from Asp481 and His464, respectively (Fig. 2 ▶ e). These distances are too large to allow cleavage of the Ub isopeptide bond. Finally, our observations with both new USP7CD structures support the notion that the orientation of the catalytic triad previously reported for USP7CD is not a crystallographic artifact, but rather a true representation of the USP7CD active site in the absence of bound Ub.

In conclusion, we have elucidated two new structures of the USP7 catalytic domain at 2.2 Å resolution. These structures revealed a loop not previously seen in the apoenzyme composed of residues 410–419 (BL1). Comparison of our apoenzyme structures with the Ub-bound structure suggests that in USP7 BL1 rearranges upon binding of Ub. Our structures also clearly show the switching loop (residues 285–291) and the catalytic triad (Cys223, Asp464 and Asp481) in unproductive conformations.

When compared with full-length USP7 (1–1102), the isolated USP7 catalytic domain (208–560) has a ∼120-fold lower catalytic activity (Faesen et al., 2011 ▶; Wrigley et al., 2011 ▶). The catalytically incompetent orientation of the active site in the absence of Ub and subsequent rearrangement upon Ub binding observed by us and others is so far unique to USP7 (Faesen et al., 2011 ▶), and significant additional structural information will be required to illuminate the still unclear mechanisms underlying the process and purpose of the active-site rearrangement. Nevertheless, USP7 remains a vital therapeutic target based on its involvement in myriad cellular processes closely connected to tumorigenesis and viral infection. Although the BL1 loop in this structure may occlude the active site, we hypothesize that the inherent flexibility of this loop (as indicated by increased BL1 loop B factors) and the available room surrounding the loop within the crystal lattice will allow it to move in order to accommodate small-molecule binding. As further progress is made in the discovery and optimization of USP7 inhibitors, rapid co-crystallization, data collection and structure elucidation will be of vital importance, and the results presented here are an important step in this direction.

Supplementary Material

PDB reference: USP7 catalytic domain, space group C2, 4m5w

PDB reference: space group P21, 4m5x

Supplementary Figure S1.. DOI: 10.1107/S2053230X14002519/tt5045sup1.tif

Supplementary Figure S2.. DOI: 10.1107/S2053230X14002519/tt5045sup2.tif

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Walther Cancer Foundation for financial support for this project and the Purdue University Center for Cancer Research for use and support of the Macromolecular Crystallography shared resource. We would also like to than the Advanced Photon Source and LS-CAT beamline staff for their continued support and assistance. Use of the Advanced Photon Source, an Office of Science User Facility operated for the US Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory, was supported by the US DOE under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. Use of the LS-CAT Sector 21 was supported by the Michigan Economic Development Corporation and the Michigan Technology Tri-Corridor (Grant 085P1000817).

Footnotes

Supporting information has been deposited in the IUCr electronic archive (Reference: TT5045).

References

- Adams, P. D. et al. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 213–221.

- Afonine, P. V., Grosse-Kunstleve, R. W. & Adams, P. D. (2005). Acta Cryst. D61, 850–855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Avvakumov, G. V., Walker, J. R., Xue, S., Finerty, P. J. Jr, Mackenzie, F., Newman, E. M. & Dhe-Paganon, S. (2006). J. Biol. Chem. 281, 38061–38070. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bergfors, T. (2003). J. Struct. Biol. 142, 66–76. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cummins, J. M., Rago, C., Kohli, M., Kinzler, K. W., Lengauer, C. & Vogelstein, B. (2004). Nature, 428, 10.1038/nature02501. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ernst, A. et al. (2013). Science, 339, 590–595.

- Everett, R. D., Meredith, M., Orr, A., Cross, A., Kathoria, M. & Parkinson, J. (1997). EMBO J. 16, 1519–1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Faesen, A. C., Dirac, A. M. G., Shanmugham, A., Ovaa, H., Perrakis, A. & Sixma, T. K. (2011). Mol. Cell, 44, 147–159. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hershko, A. & Ciechanover, A. (1998). Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67, 425–479. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hu, M., Li, P., Li, M., Li, W., Yao, T., Wu, J.-W., Gu, W., Cohen, R. E. & Shi, Y. (2002). Cell, 111, 1041–1054. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hu, M., Li, P., Song, L., Jeffrey, P. D., Chenova, T. A., Wilkinson, K. D., Cohen, R. E. & Shi, Y. (2005). EMBO J. 24, 3747–3756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Li, M., Brooks, C. L., Kon, N. & Gu, W. (2004). Mol. Cell, 13, 879–886. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Nicholson, B., Marblestone, J. G., Butt, T. R. & Mattern, M. R. (2007). Future Oncol. 3, 191–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Otwinowski, Z. & Minor, W. (1997). Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Renatus, M., Parrado, S. G., D’Arcy, A., Eidhoff, U., Gerhartz, B., Hassiepen, U., Pierrat, B., Riedl, R., Vinzenz, D., Worpenberg, S. & Kroemer, M. (2006). Structure, 14, 1293–1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Reyes-Turcu, F. E., Ventii, K. H. & Wilkinson, K. D. (2009). Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78, 363–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Song, M. S., Salmena, L., Carracedo, A., Egia, A., Lo-Coco, F., Teruya-Feldstein, J. & Pandolfi, P. P. (2008). Nature (London), 455, 813–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wrigley, J. D., Eckersley, K., Hardern, I. M., Millard, L., Walters, M., Peters, S. W., Mott, R., Nowak, T., Ward, R. A., Simpson, P. B. & Hudson, K. (2011). Cell Biochem. Biophys. 60, 99–111. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PDB reference: USP7 catalytic domain, space group C2, 4m5w

PDB reference: space group P21, 4m5x

Supplementary Figure S1.. DOI: 10.1107/S2053230X14002519/tt5045sup1.tif

Supplementary Figure S2.. DOI: 10.1107/S2053230X14002519/tt5045sup2.tif