Abstract

Background and objectives

AKI is associated with major adverse kidney events (MAKE): death, new dialysis, and worsened renal function. CKD (arising from worsened renal function) is associated with a higher risk of major adverse cardiac events (MACE): myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, and heart failure. Therefore, the study hypothesis was that veterans who develop AKI during hospitalization for an MI would be at higher risk of subsequent MACE and MAKE.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

Patients in the Veterans Affairs (VA) database who had a discharge diagnosis with International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, code of 584.xx (AKI) or 410.xx (MI) and were admitted to a VA facility from October 1999 through December 2005 were selected for analysis. Three groups of patients were created on the basis of the index admission diagnosis and serum creatinine values: AKI, MI, or MI with AKI. Patients with mean baseline estimated GFR<45 ml/min per 1.73 m2 were excluded. The primary outcomes assessed were mortality, MAKE, and MACE during the study period (maximum of 6 years). The combination of MAKE and MACE—major adverse renocardiovascular events (MARCE)—was also assessed.

Results

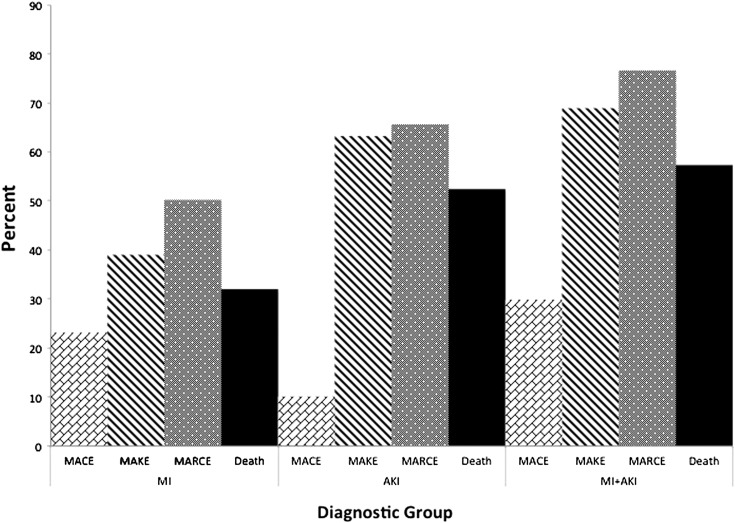

A total of 36,980 patients were available for analysis. Mean age±SD was 66.8±11.4 years. The most deaths occurred in the MI+AKI group (57.5%), and the fewest (32.3%) occurred in patients with an uncomplicated MI admission. In both the unadjusted and adjusted time-to-event analyses, patients with AKI and AKI+MI had worse MARCE outcomes than those who had MI alone (adjusted hazard ratios, 1.37 [95% confidence interval, 1.32 to 1.42] and 1.92 [1.86 to 1.99], respectively).

Conclusions

Veterans who develop AKI in the setting of MI have worse long-term outcomes than those with AKI or MI alone. Veterans with AKI alone have worse outcomes than those diagnosed with an MI in the absence of AKI.

Introduction

AKI is a common disorder that complicates the hospital course of many patients (1–4). The incidence of AKI is increasing, and the mortality of AKI remains unacceptably high (3,4). AKI is linked with an independent risk of death in multiple cohort studies (5,6). Although the early hazard of AKI has been demonstrated, the long-term consequences of AKI in survivors are not as well appreciated. More recently, multiple large cohort studies have demonstrated that patients who survive an episode of AKI are at risk for progression to advanced stages of CKD (7–12). As a consequence of these findings, the composite endpoint of major adverse kidney events (MAKE) (13) has been endorsed by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases clinical trials workgroup to harmonize and encourage future clinical trials (14–16).

Because patients who develop AKI and CKD also tend to have risk factors for cardiovascular disease (e.g., diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia), some authors have suggested that the increased cardiovascular events and excess mortality outcomes seen in patients with kidney disease (both AKI and CKD) are largely an epiphenomenon due to shared risk factors (7,17–21). AKI is associated with the development of CKD, and CKD is also a robust risk factor for major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) (22). Therefore, patients who sustain AKI and then develop CKD will be at risk for developing cardiovascular events.

We hypothesized that patients who develop AKI are at risk for future MACE and MAKE. In this study we compared the renal and cardiovascular outcomes of patients with AKI, myocardial infarction (MI), and both MI and AKI. We also assessed the development of the combination of MACE and MAKE, a term we refer to as major adverse renocardiovascular events (MARCE).

Materials and Methods

Patients

All patients in the Veterans Affairs (VA) Decision Support System database who had an admission from October 1999 through December 2005 with a primary discharge diagnosis for International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9), code of 584.xx (AKI) or 410.xx (MI) were selected for analysis. Each of these ICD-9 codes is highly specific for its respective diagnoses (23–25). The first such admission during this period was defined as the index admission. For this admission, all serum creatinine (SC) and albumin (SAlb) laboratory evaluations during the previous year (baseline) and for up to 6 years following admission were examined.

Three groups of patients were identified on the basis of the ICD-9 diagnosis of the index admission and SC values: (1) AKI group (patients with AKI ICD-9 diagnosis and an increase in SC to a level corresponding to stage 1, 2, or 3 of the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes [KDIGO] criteria) (26); (2) MI without an increase in SC; and (3) MI with an increase in SC values to a level corresponding to stage 1, 2, or 3 of the KDIGO criteria. KDIGO criteria for this analysis were defined as a peak SC during admission at least 1.5–1.9 times higher than baseline or an increase of ≥0.3 mg/dl (stage 1), an increase of at least 2.0–2.9 times baseline (stage 2), or an increase of ≥3.0 times baseline or ≥4.0 mg/dl (stage 3). Urine output criteria for KDIGO criteria were not assessed. Thus, the patients in the AKI and the MI+AKI groups had AKI validated by their SC values in addition to their primary discharge diagnosis for the index admission. Patients who had progressed to CKD stage 3b, 4, or 5 before their index admission; those who started long-term dialysis; those with mean baseline estimated GFR (eGFR)<45 ml/min per 1.73 m2; and those with no SC evaluations during baseline were not included in the analysis (26). Patients with a 25% decrease in eGFR during the year before admission were also excluded. Patients with admissions for AKI followed by MI (or vice-versa) were kept in the analysis.

Variables

For each patient in the sample, we collected every SC and SAlb date and value during the study period. We computed eGFR from SC, sex, age, and race using the CKD-Epidemiology Collaboration formula (27). Any eGFR values >120 ml/min per 1.73 m2 were recoded to 120 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (Figure 1). The date on which eGFR decreased by 25% was defined as the first date on which eGFR decreased to ≤75% of the mean baseline eGFR and never again increased above 75% of the baseline value for that patient, as previously described (7). Long-term dialysis was defined as having >13 outpatient dialysis treatments during any 60-day period, with the start date defined as the date of the first of these treatments (7). Primary diagnoses for all outpatient visits during the study period were examined. Patients were coded as positive for pre–index-admission hypertension if they had visits with an ICD-9 code of 401.xx and as positive for diabetes if they had clinic visits with a code of 250.xx before the admission date for the index admission (7). Dates of all admissions during the study period with discharge diagnoses of MI (ICD-9 code, 410.xx), heart failure (428.xx), coronary artery disease/coronary atherosclerosis (414.xx), and stroke (434.xx, 435.xx, or 436.xx) were recorded. Each of these ICD-9 codes is highly specific for its respective diagnosis (24,28). Patients with outpatient visits before the index admission with primary diagnosis ICD-9 codes of 401.xx or 250.xx were coded as having hypertension and diabetes, respectively. Patients with pre–index-admission inpatient stays with primary diagnosis ICD-9 codes of 434.xx, 435.xx, or 436.xx were coded as having stroke, and those with a code of 414.xx were coded as positive for coronary artery disease (CAD).

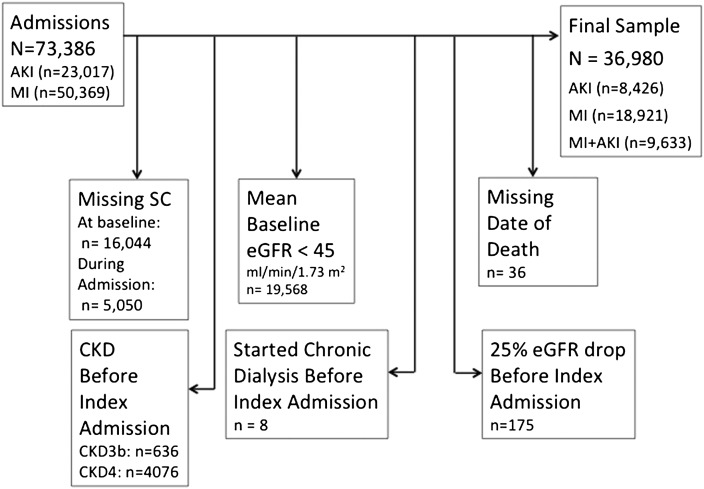

Figure 1.

Patient flow into the study. Of the patients excluded, some had multiple criteria for exclusion. eGFR, estimated GFR; MI, myocardial infarction; SC, serum creatinine concentration.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes assessed were mortality, MAKE, and MACE during the study period (maximum of 6 years depending on the index hospitalization). Date of death was available from the VA Beneficiary Identification Records Locator Subsystem Death File, which is updated weekly with data from the Social Security Administration. Secondary outcomes were as follows: MACE was coded as positive for patients who had at least one subsequent admission for stroke, congestive heart failure, or MI following the index admission. MAKE was coded as positive for patients who, after the index admission, underwent long-term dialysis, had a 25% decrease in eGFR, or died. MARCE was defined as having MAKE or MACE or both. The dates of MAKE, MACE, and MARCE were defined as the date of the first qualifying event.

Statistical Analyses

All data were extensively checked for out-of-range values. The Pearson chi-squared test was used to examine associations between diagnostic group and binary outcomes. Several multivariate analyses were then used to correct for potential confounding variables, including age; race; sex; baseline renal function; and preadmission hypertension, CAD, stroke, or diabetes. Time-to-event analyses were then used to assess differences between diagnostic groups in the rate at which patients reached each endpoint: death, MACE, MAKE, and MARCE. For each of the four outcome variables, Kaplan–Meier analysis was used to examine univariate differences between groups. Cox regression was used to correct the time-to-event estimates for the effects of covariates.

To further assess the effect of outcomes, the primary analysis was conducted with the subset of patients with MI who had an ICD-9 code specific for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) (ICD-9 codes of 410.0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, and 0.8). Using the same methods described above, we created a STEMI group and a STEMI+AKI group; we compared these groups with the AKI cohort. We also conducted a stratified analysis by baseline eGFR tertile, and we conducted a sensitivity analysis in which we substituted the lowest eGFR during admission for patients with missing baseline SC values.

SAS software, version 9.2 (Cary, NC), was used for all statistical analyses, including the Freq, Lifetest, and Phreg procedures.

Results

The initial sample had 73,386 patients with admissions during the study period for AKI (n=23,017) or MI (n=50,369) for whom the dataset contained valid SC data. Of these patients, 16,044 were dropped because they had no SC values before the index admission date; 5050 patients with no SC values during admission were dropped because we could not determine their KDIGO status during the index admission. We withdrew 19,568 patients because their mean baseline eGFR was <45 ml/min per 1.73 m2, 4712 patients because they entered CKD stage 3b before their index admission, and 8 patients because they started long-term dialysis before the index admission date. These exclusion criteria were not mutually exclusive. This left a final sample of 36,980 patients whose data were used in the subsequent analyses (AKI, 8426; MI, 18,921; MI+AKI, 9633) (Figure 1).

The mean age of the study sample±SD was 66.8±11.4 years; 1.5% of patients were female; 18.7% were African American, and 73.6% were white (Table 1). Lengths of stay for the index admission were longest in the MI+AKI group and shortest in the MI group. Baseline eGFR was lower in the AKI group than the other groups.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and outcomes, by diagnostic group.

| Variable | MI (n=18,921) | AKI (n=8426) | MI+AKI (n=9633) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preadmission | |||

| Age (yr) | 65.5±11.2 | 66.4±12.0 | 69.7±10.7 |

| Race | |||

| African American | 2954 (15.6) | 2172 (25.8) | 1773 (18.4) |

| Hispanic | 1061 (5.6) | 541 (6.4) | 622 (6.5) |

| White | 14,590 (77.1) | 5566 (66.1) | 7054 (73.2) |

| Other | 309 (1.7) | 139 (1.6) | 172 (1.8) |

| Unknown | 7 (0.04) | 8 (0.1) | 12 (0.1) |

| Women | 278 (1.5) | 170 (2.0) | 118 (1.2) |

| Median index admission LOS (d) (IQR) | 4.0 (2.0–6.0) | 4.0 (3.0–8.0) | 6.0 (3.0–11.0) |

| Median baseline SC evaluations (n) (IQR) | 3.0 (1.0–5.0) | 6.0 (3.0–13.0) | 3.0 (2.0–6.0) |

| Mean baseline eGFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 75.7±16.7 | 68.4±17.4 | 70.4±16.7 |

| Mean baseline albumin (g/dl) | 3.9±0.4 | 3.6±0.6 | 3.8±0.5 |

| Albumin<3 g/dl | 296 (1.6) | 883 (10.5) | 358 (3.7) |

| Albumin≥3 g/dl | 11,641 (61.5) | 5236 (62.1) | 5638 (58.5) |

| Unknown albumin value | 6984 (36.9) | 2307 (27.4) | 3637 (37.8) |

| Diabetes | 6330 (33.5) | 3425 (40.7) | 4334 (45.0) |

| Hypertension | 10944(57.8) | 5503 (65.3) | 5845 (60.7) |

| CAD | 2109 (11.2) | 560 (6.6) | 988 (10.3) |

| Stroke | 372 (2.0) | 235 (2.8) | 281 (2.9) |

| AKI stage | |||

| KDIGO stage 1 | NA | 1958 (23.2) | 7561 (78.5) |

| KDIGO stage 2 | NA | 2338 (27.7) | 1385 (14.4) |

| KDIGO stage 3 | NA | 4130 (49.0) | 687 (7.1) |

| Outcomes | |||

| 25% eGFR decrease | 2584 (13.7) | 2944 (34.9) | 3903 (40.5) |

| Long-term dialysis | 13 (0.1) | 48 (0.6) | 12 (0.1) |

| MI admission | 3082 (16.3) | 168 (2.0) | 1721 (17.9) |

| CHF admission | 1433 (7.6) | 647 (7.6) | 1396 (14.5) |

| Stroke admission | 385 (2.0) | 110 (1.3) | 206 (2.1) |

| Death | 6102 (32.3) | 4471 (53.1) | 5537 (57.5) |

| MACE | 4375 (23.1) | 859 (10.2) | 2881 (29.9) |

| MAKE | 7351 (39.0) | 5092 (60.4) | 6558 (68.1) |

| MARCE | 9460 (50.1) | 5370 (63.7) | 7326 (76.1) |

Groups differed significantly on all outcomes and preadmission variables (P<0.001). Unless otherwise noted, values are the number (percentage) of patients. Mean values are expressed with SDs. MI, myocardial infarction; LOS, length of stay; IQR, interquartile range; eGFR, estimated GFR; CAD, coronary artery disease; KDIGO, Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes; NA, not applicable; CHF, congestive heart failure; MACE, major adverse cardiac events (stroke, congestive heart failure, or MI admission); MAKE, major adverse kidney events (death, dialysis, or eGFR decrease of 25% from mean baseline level); MARCE, major adverse renal or cardiac events (MACE or MAKE).

Univariate Results

Median follow-up was 1.4 years after the index admission (interquartile range, 0.5–3.4 years). The most deaths occurred in the MI+AKI group (57.5%), and the fewest (32.3%) occurred in the MI group (Table 1).

Death.

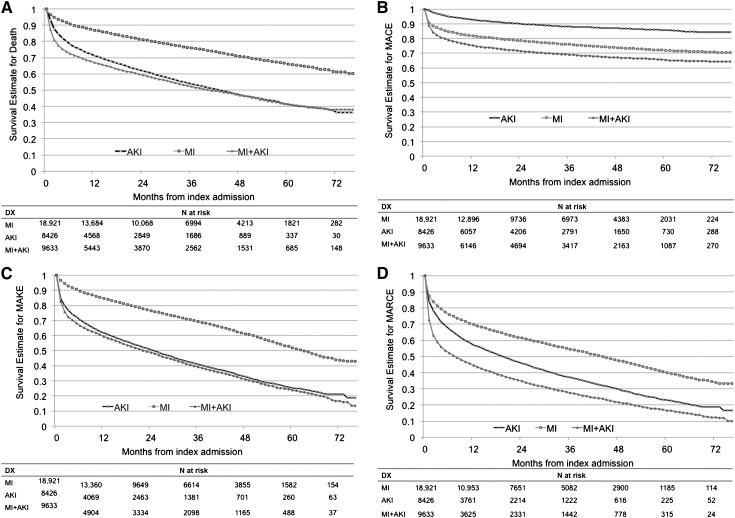

Kaplan–Meier analysis was used to account for the timing of events relative to the index admission date (Figure 2). The likelihood of dying during the follow-up period differed significantly between groups (log-rank statistic P<0.001). The survival estimates (Figure 2A) show clear differentiation 1 year after index admission, with Kaplan–Meier survival estimates of 0.86 for patients with MI, 0.70 for those with AKI, and 0.66 for those with MI+AKI. Survival rates 5 years after index admission were 0.66, 0.41, and 0.41 for the MI, AKI, and MI+AKI, groups, respectively. Confidence intervals (CIs) for these estimates are shown in Supplemental Table 1.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier event rate estimates over time, by diagnostic group. (A) Death. (B) Major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE). (C) Major adverse kidney events (MAKE). (D) Major adverse renocardiovascular events (MARCE). The curves display the cumulative survival probability over time. The observation time started at the index admission, thus the follow-up time varied across patients. DX, diagnosis.

MACE.

Time-to-event functions for MACE differed significantly between groups (log-rank P<0.001). One year after admission, the MI and MI+AKI groups had a higher MACE event probability than the AKI group (Figure 2B). Estimates of the percentage of patients free of MACE at 1 year were 0.81 in the MI group, 0.75 in the MI+AKI group, and 0.93 in the AKI group.

MAKE.

Time-to-event functions for MAKE differed significantly between groups (log-rank P<0.001) (Figure 2C). The percentages of patients free of MAKE events 1 year after admission were 0.84, 0.61, and 0.58 in the MI, AKI, and MI+AKI groups, respectively. Five years after admission, the estimates were 0.51, 0.25, and 0.24.

MARCE.

Time-to-event functions for MARCE differed significantly between groups (log-rank P<0.001) (Figure 2D). The percentages of patients free of MARCE events at 1 year were 0.69, 0.56, and 0.43 in the MI, AKI, and MI+AKI groups. At 5 years, the percentage of patients free of MARCE were 0.40, 0.23, and 0.16 for the MI, AKI, and MI+AKI groups, respectively. Outcomes across diagnostic groups are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Outcomes across diagnostic groups.

Multivariate Results

Cox regression models were tested for four outcomes: death, MACE, MAKE, and MARCE. We selected covariates that have been shown to predict CKD after AKI and covariates linked to cardiovascular outcomes (7–9,29). In each model, the covariates included diagnosis, sex, African American race, age>80 years, mean eGFR during baseline, preadmission diabetes or hypertension, history of CAD, previous stroke, and baseline serum SAlb<3 g/dl. Each of these four models was significant (likelihood ratio chi-squared P<0.001).

In the Cox regression model for time from index admission to death, after correcting for all covariates, the hazard ratios (HRs) for the AKI and MI + AKI groups were 1.85 (95% CI, 1.76 to 1.94) and 2.14 (95% CI, 2.05 to 2.23), respectively (with MI used as the reference group; all P<0.001), indicating that the risk of death during the follow-up period was almost twice as high for patients with AKI and more than twice as high for those with MI+AKI compared with those with MI (Table 2). Other predictors with a significant independent association included eGFR (higher eGFR was associated with lower risk for death), sex (female sex was associated with lower risk), age >80 years (older patients were at higher risk), diabetes (patients with diabetes were at higher risk), diagnosis of hypertension or CAD (both associated with lower risk), previous stroke (associated with higher risk), and SAlb <3 g/dl (associated with higher risk) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Cox regression hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals for four outcomes

| Predictor | Death | MACE | MAKE | MARCE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AKI | 1.85 (1.76 to 1.94) | 0.40 (0.38 to 0.44) | 2.07 (1.99 to 2.16) | 1.37 (1.32 to 1.42) |

| MI+AKI | 2.14 (2.05 to 2.23) | 1.24 (1.18 to 1.30) | 2.30 (2.21 to 2.38) | 1.92 (1.86 to 1.99) |

| eGFR>100 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 0.60 (0.54 to 0.66) | 0.64 (0.56 to 0.72) | 0.71 (0.66 to 0.78) | 0.73 (0.68 to 0.79) |

| eGFR>90–100 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 0.65 (0.60 to 0.71) | 0.68 (0.61 to 0.75) | 0.77 (0.71 to 0.83) | 0.78 (0.73 to 0.83) |

| eGFR>80–90 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 0.76 (0.71 to 0.82) | 0.69 (0.63 to 0.76) | 0.86 (0.81 to 0.92) | 0.84 (0.79 to 0.89) |

| eGFR>70–80 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 0.77 (0.72 to 0.82) | 0.79 (0.72 to 0.86) | 0.87 (0.82 to 0.93) | 0.88 (0.83 to 0.93) |

| eGFR>60–70 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 0.85 (0.80 to 0.91) | 0.85 (0.78 to 0.93) | 0.93 (0.88 to 0.99) | 0.94 (0.89 to 0.99) |

| eGFR>50–60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 0.98 (0.92 to 1.05) | 0.91 (0.83 to 0.99) | 1.01 (0.95 to 1.07) | 0.99 (0.94 to 1.05) |

| Sex (female) | 0.66 (0.55 to 0.77) | 0.84 (0.69 to 1.03) | 0.79 (0.69 to 0.90) | 0.82 (0.73 to 0.92) |

| African American race | 1.14 (1.09 to 1.19) | 1.05 (0.99 to 1.11) | 1.09 (1.05 to 1.14) | 1.06 (1.03 to 1.10) |

| Age>80 yr | 2.15 (2.06 to 2.25) | 0.99 (0.93 to 1.05) | 1.92 (1.84 to 1.996) | 1.59 (1.53 to 1.65) |

| Diabetes | 1.10 (1.06 to 1.14) | 1.37 (1.31 to 1.43) | 1.23 (1.19 to 1.27) | 1.22 (1.18 to 1.25) |

| Hypertension | 0.79 (0.76 to 0.82) | 0.98 (0.94 to 1.03) | 0.91 (0.88 to 0.94) | 0.93 (0.90 to 0.95) |

| Serum albumin<3 g/dl | 2.35 (2.19 to 2.51) | 0.83 (0.72 to 0.95) | 2.22 (2.08 to 2.36) | 1.82 (1.71 to 1.93) |

| CAD | 0.93 (0.87 to 0.99) | 1.34 (1.25 to 1.42 | 0.94 (0.89 to 0.99) | 1.03 (0.98 to 1.08) |

| Stroke | 1.37 (1.23 to 1.52) | 1.16 (1.01 to 1.32) | 1.39 (1.27 to 1.52) | 1.29 (1.19 to 1.40) |

The reference group for diagnosis was MI (this was done because MI has the best survival). The reference group for eGFR was ≤50 ml/min per 1.73 m2. CAD, coronary artery disease.

In the model predicting time to MACE, the HRs for the AKI and MI+AKI groups were 0.40 (95% CI, 0.38 to 0.44) and 1.24 (95% CI, 1.18 to 1.30), respectively (with MI used as the reference group; all P<0.001). Other predictors with significant independent associations with MACE included eGFR (higher eGFR was associated with lower risk), diabetes, previous stroke, and history of CAD (all associated with higher risk) (Table 2).

HRs for MAKE for the AKI and MI+AKI groups were 2.07 (95% CI, 1.99 to 2.16) and 2.30 (95% CI, 2.21 to 2.38), respectively (with MI used as the reference group; all P<0.001). Higher baseline eGFR (P<0.001), female sex, and treatment for hypertension (different from hypertension per se) were associated with a lower risk, whereas African American race, age>80 years, diabetes, previous stroke, and SAlb<3 g/dl were independently associated with increased risk of reaching the MAKE endpoint.

In the overall composite endpoint (MARCE), HRs for the AKI and MI+AKI groups were 1.37 (95% CI, 1.32 to 1.42) and 1.92 (95% CI, 1.86 to 1.99). Higher baseline eGFR (P<0.001), female sex, and hypertension were associated with lower risk of reaching MARCE, whereas African American race, age>80 years, diabetes, previous stroke, and SAlb<3 g/dl were associated with higher risk of reaching MARCE.

Sensitivity Analyses

When patients without a STEMI were removed from the prior analysis, the same patterns were maintained as when they were included (Table 3). Patients with AKI alone were more than twice as likely to die than patients with a STEMI alone (HR, 2.24; 95% CI, 2.08 to 2.41) after correcting for covariates.

Table 3.

Kaplan–Meier and Cox regression results for AKI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, and ST-segment myocardial infarction+AKI

| Outcome | Log-Rank Chi-Square (P Value) | Cox HR for AKI versus STEMI (95% CI) (P Value) | Cox HR for STEMI+AKI versus STEMI (95% CI) (P Value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Death | 875.6 (P<0.001) | 2.24 (2.08 to 2.41) (P<0.001) | 2.41 (2.21 to 2.63) (P<0.001) |

| MACE | 552.5 (P<0.001) | 0.43 (0.39 to 0.47) (P<0.001) | 1.29 (1.17 to 1.42) (P<0.001) |

| MAKE | 1394.9 (P<0.001) | 2.45 (2.30 to 2.61) (P<0.001) | 2.57 (2.39 to 2.77) (P<0.001) |

| MARCE | 809.5 (P<0.001) | 1.54 (1.46 to 1.63) (P<0.001) | 2.15 (2.02 to 2.30) (P<0.001) |

Analysis adjusted for age, sex, race, baseline estimated GFR, diabetes, hypertension, serum albumin level, history of previous stroke, and presence of coronary artery disease. HR, hazard ratio; STEMI, ST-segment myocardial infarction; CI, confidence interval.

Two additional sensitivity analyses (one stratified by eGFR tertile and the other using lowest during-admission eGFR for patients with missing preadmission SC values) produced results that did not substantively differ from the above findings (Supplemental Table 2).

Outcomes were examined in subgroups of patients in the AKI and AKI+MI groups, stratified by AKI severity (Supplemental Table 3). As AKI severity increased, so did the incidence of death, MACE and death, MAKE, and MARCE in the AKI+MI group. Even patients in the MI+AKI group who had the lowest severity (KDIGO category 1) had higher rates of each outcome than did the patients with MI.

Discussion

In this study of United States veterans, a multivariable analysis adjusted for renal and cardiovascular risk factors showed that patients with an index inpatient diagnosis of MI had the best survival compared with those with an index inpatient diagnosis of AKI or MI + AKI (Figure 2, Table 2). This finding remained present even when severity of AKI was assessed (Supplemental Table 3) and also remained present when patients with STEMI were compared with those with AKI and STEMI+AKI in a multivariable Cox model (Table 3).

The second aim of our study was to determine the incidence of MAKE, MACE, and MARCE, because these are proposed composite endpoints of clinical trials (14,15). Our analysis showed that patients who experienced an episode of AKI were at significant risk for death and permanent loss of renal function. During 6 years of follow-up, 53.1% of patients with AKI died and 62.5% developed MAKE. Perhaps more saliently, compared with patients in the MI group, those hospitalized for MI complicated by AKI had a marked increase in episodes of MAKE, MACE, and MARCE (Figure 2, Table 1). Thus, when AKI complicated MI, the overall event rates for death and all composite endpoints increased. This finding was confirmed in multivariate time-to-event analyses (Table 2).

Our findings that AKI is associated with long-term cardiovascular events, even after multivariable adjustment (Table 2), confirm the findings of a smaller study (30). Our finding that patients with MI+AKI have twice the adjusted mortality risk of patients with MI alone is consistent with findings from previous cohort studies (31,32). In addition to the risk of death, some smaller studies have suggested that when MI is complicated by AKI, the risk of long-term cardiovascular events is increased (32–34). One observational study of approximately 15,000 patients undergoing coronary angiography (a majority of whom had acute coronary syndrome) showed a long-term risk of MACE (32). We confirm these findings in >28,000 patients with MI, showing that those with MI+AKI are more likely to develop MACE and almost twice as likely to be admitted for congestive heart failure compared with patients with MI alone (Figure 2, Table 1). We also showed that MI complicating AKI increases the incidence of MAKE, suggesting that the deleterious effect of acute heart failure or AKI is bidirectional. In aggregate, these data suggest that when AKI complicates MI, there is significant long-term risk for the development of cardiorenal syndrome (35).

In general, administrative database studies rarely have adequate granularity to account for all the possible aspects that influence outcome (4,8,36–39). These types of studies are valuable for hypothesis generation and revealing important associations. In this study, all circumstances that cause AKI in the dataset cannot be fully ascertained. However, the striking finding remains that an “exposure” of AKI portends severe renal and cardiovascular outcomes compared with a patient group with similar cardiovascular risk factors (MI group). We believe that this observation—that an AKI exposure is potentially worse for an individual than is a STEMI exposure—is novel and may be of great importance to funding agencies and public health officials.

In addition, when AKI complicates MI, renal, cardiovascular, and mortality outcomes are all worsened (Table 1). Some of this amplification may be because the development of AKI in these diseases is a surrogate for increased severity of illness. However, many of the observed MARCE events occur months to years after the index hospitalization, suggesting that acute cardiorenal injury may induce a vicious cycle that persists long after the acute event. The link between AKI and downstream cardiovascular events is plausible. Studies suggest that “organ cross-talk” may be active long after the initial injury. Preclinical models demonstrate that AKI can result in distant organ effects that include cardiac cell apoptosis and cardiac leukocyte infiltration (40). In a review, Ratliff and colleagues conclude that “AKI is a paradigm of a localized damage triggering systemic inflammatory disease,” and when that inflammatory response is severe or prolonged, it may involve other organs (heart, lungs, and liver) (41,42).

This study has several strengths. First, it was undertaken with a large sample with access to longitudinal data. Second, the ICD-9 codes we used are highly specific for their respective diagnoses, and we had access to the inpatient serum creatinine values to further confirm the presence of AKI. Third, we had access to postdischarge diagnostic information and serial SC measurements relevant to the composite endpoints for MAKE, MACE, and MARCE.

This study also, however, has several limitations. Because we are unable to discern the severity of illness of patients with MI who developed AKI during their index hospitalization, we may have overestimated the effect of AKI per se as a surrogate for severity of illness. However, our findings are consistent with other smaller cohort reports (30,32). In addition, we used ICD-9 codes that tend to be specific for their respective diagnoses and that may have biased the AKI group to patients with more severe AKI. We were unable to adjust for some comorbid conditions (such as liver disease and malignancy) and socioeconomic status, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Because this is a cohort of veterans, the population is older and overwhelmingly male. However, there are no a priori reasons to suspect outcomes for similar patients or women in other populations would be substantially different (7,29). Because we were not able to link our database with the US Renal Data System dataset, our reported rate for the need for long-term dialysis is probably underestimated. However, that aspect of the MAKE and MARCE endpoint was captured by the 25% loss in baseline eGFR.

In conclusion, our data strengthen and further delineate evidence linking AKI and its severity in hospitalized patients either as a primary diagnosis or in association with other critical illness, such as MI, to increased long-term mortality and composite outcomes, such as MAKE, MACE, and MARCE. Furthermore, poor outcomes associated with AKI exceed those of an MI, a disease that carries a much higher public health profile, and whose prevention attracts very high levels of government and nongovernment funding. We also propose that composite endpoints (MAKE, MACE, and MARCE) be used in future clinical trials of AKI, because they provide a method that improves the ability to detect meaningful differences in therapeutic interventions (14–16). Finally, improved prevention and therapy of AKI, as well as follow-up surveillance of this high-risk group, are urgently required.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

This project was approved by the institutional review board and Research and Development Committee of the Washington, DC, VA Medical Center.

The authors express their gratitude to Dr. Paul Eggers (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases), to Mr. David Lyle and Dr. George J. Busch (Clinical User Support, Veterans Administration Decision Support System), and to Mr. Robert Williamson (Information Resource Management, Washington, DC, VA Medical Center) for their valuable assistance with data collection.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.02440213/-/DCSupplemental.

See related editorial, “AKI: Not Just a Short-Term Problem?,” on pages 435–436.

References

- 1.Uchino S, Kellum JA, Bellomo R, Doig GS, Morimatsu H, Morgera S, Schetz M, Tan I, Bouman C, Macedo E, Gibney N, Tolwani A, Ronco C, Beginning and Ending Supportive Therapy for the Kidney (BEST Kidney) Investigators : Acute renal failure in critically ill patients: A multinational, multicenter study. JAMA 294: 813–818, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waikar SS, Liu KD, Chertow GM: Diagnosis, epidemiology and outcomes of acute kidney injury. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 844–861, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waikar SS, Curhan GC, Wald R, McCarthy EP, Chertow GM: Declining mortality in patients with acute renal failure, 1988 to 2002. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 1143–1150, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xue JL, Daniels F, Star RA, Kimmel PL, Eggers PW, Molitoris BA, Himmelfarb J, Collins AJ: Incidence and mortality of acute renal failure in Medicare beneficiaries, 1992 to 2001. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 1135–1142, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chertow GM, Levy EM, Hammermeister KE, Grover F, Daley J: Independent association between acute renal failure and mortality following cardiac surgery. Am J Med 104: 343–348, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coca SG, Bauling P, Schifftner T, Howard CS, Teitelbaum I, Parikh CR: Contribution of acute kidney injury toward morbidity and mortality in burns: A contemporary analysis. Am J Kidney Dis 49: 517–523, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amdur RL, Chawla LS, Amodeo S, Kimmel PL, Palant CE: Outcomes following diagnosis of acute renal failure in U.S. veterans: Focus on acute tubular necrosis. Kidney Int 76: 1089–1097, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wald R, Quinn RR, Luo J, Li P, Scales DC, Mamdani MM, Ray JG, University of Toronto Acute Kidney Injury Research Group : Chronic dialysis and death among survivors of acute kidney injury requiring dialysis. JAMA 302: 1179–1185, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lo LJ, Go AS, Chertow GM, McCulloch CE, Fan D, Ordoñez JD, Hsu CY: Dialysis-requiring acute renal failure increases the risk of progressive chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 76: 893–899, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishani A, Xue JL, Himmelfarb J, Eggers PW, Kimmel PL, Molitoris BA, Collins AJ: Acute kidney injury increases risk of ESRD among elderly. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 223–228, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coca SG, Singanamala S, Parikh CR: Chronic kidney disease after acute kidney injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Kidney Int 81: 442–448, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chawla LS, Kimmel PL: Acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease: An integrated clinical syndrome. Kidney Int 82: 516–524, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shaw A: Models of preventable disease: contrast-induced nephropathy and cardiac surgery-associated acute kidney injury. Contrib Nephrol 174: 156–162, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okusa MD, Molitoris BA, Palevsky PM, Chinchilli VM, Liu KD, Cheung AK, Weisbord SD, Faubel S, Kellum JA, Wald R, Chertow GM, Levin A, Waikar SS, Murray PT, Parikh CR, Shaw AD, Go AS, Chawla LS, Kaufman JS, Devarajan P, Toto RM, Hsu CY, Greene TH, Mehta RL, Stokes JB, Thompson AM, Thompson BT, Westenfelder CS, Tumlin JA, Warnock DG, Shah SV, Xie Y, Duggan EG, Kimmel PL, Star RA: Design of clinical trials in acute kidney injury: A report from an NIDDK workshop—prevention trials. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 851–855, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palevsky PM, Molitoris BA, Okusa MD, Levin A, Waikar SS, Wald R, Chertow GM, Murray PT, Parikh CR, Shaw AD, Go AS, Faubel SG, Kellum JA, Chinchilli VM, Liu KD, Cheung AK, Weisbord SD, Chawla LS, Kaufman JS, Devarajan P, Toto RM, Hsu CY, Greene T, Mehta RL, Stokes JB, Thompson AM, Thompson BT, Westenfelder CS, Tumlin JA, Warnock DG, Shah SV, Xie Y, Duggan EG, Kimmel PL, Star RA: Design of clinical trials in acute kidney injury: Report from an NIDDK workshop on trial methodology. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 844–850, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Molitoris BA, Okusa MD, Palevsky PM, Chawla LS, Kaufman JS, Devarajan P, Toto RM, Hsu CY, Greene TH, Faubel SG, Kellum JA, Wald R, Chertow GM, Levin A, Waikar SS, Murray PT, Parikh CR, Shaw AD, Go AS, Chinchilli VM, Liu KD, Cheung AK, Weisbord SD, Mehta RL, Stokes JB, Thompson AM, Thompson BT, Westenfelder CS, Tumlin JA, Warnock DG, Shah SV, Xie Y, Duggan EG, Kimmel PL, Star RA: Design of clinical trials in AKI: A report from an NIDDK workshop. Trials of patients with sepsis and in selected hospital settings. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 856–860, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chawla LS, Seneff MG, Nelson DR, Williams M, Levy H, Kimmel PL, Macias WL: Elevated plasma concentrations of IL-6 and elevated APACHE II score predict acute kidney injury in patients with severe sepsis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2: 22–30, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chawla LS, Abell L, Mazhari R, Egan M, Kadambi N, Burke HB, Junker C, Seneff MG, Kimmel PL: Identifying critically ill patients at high risk for developing acute renal failure: a pilot study. Kidney Int 68: 2274–2280, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thakar CV, Arrigain S, Worley S, Yared JP, Paganini EP: A clinical score to predict acute renal failure after cardiac surgery. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 162–168, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu KD, Glidden DV, Eisner MD, Parsons PE, Ware LB, Wheeler A, Korpak A, Thompson BT, Chertow GM, Matthay MA, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute ARDS Network Clinical Trials Group : Predictive and pathogenetic value of plasma biomarkers for acute kidney injury in patients with acute lung injury. Crit Care Med 35: 2755–2761, 2007 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murugan R, Karajala-Subramanyam V, Lee M, Yende S, Kong L, Carter M, Angus DC, Kellum JA, Genetic and Inflammatory Markers of Sepsis (GenIMS) Investigators : Acute kidney injury in non-severe pneumonia is associated with an increased immune response and lower survival. Kidney Int 77: 527–535, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY: Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med 351: 1296–1305, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waikar SS, Wald R, Chertow GM, Curhan GC, Winkelmayer WC, Liangos O, Sosa MA, Jaber BL: Validity of International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification Codes for Acute Renal Failure. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 1688–1694, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Metcalfe A, Neudam A, Forde S, Liu M, Drosler S, Quan H, Jette N: Case definitions for acute myocardial infarction in administrative databases and their impact on in-hospital mortality rates. Health Serv Res 48: 290–318, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fry AM, Shay DK, Holman RC, Curns AT, Anderson LJ: Trends in hospitalizations for pneumonia among persons aged 65 years or older in the United States, 1988-2002. JAMA 294: 2712–2719, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kidney Disease : Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Acute Kidney Injury Work Group: KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Kidney Injury. Kidney Int Suppl 2: 1–138, 2012. 11904577 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF, 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J, CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) : A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150: 604–612, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Birman-Deych E, Waterman AD, Yan Y, Nilasena DS, Radford MJ, Gage BF: Accuracy of ICD-9-CM codes for identifying cardiovascular and stroke risk factors. Med Care 43: 480–485, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chawla LS, Amdur RL, Amodeo S, Kimmel PL, Palant CE: The severity of acute kidney injury predicts progression to chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 79: 1361–1369, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choi AI, Li Y, Parikh C, Volberding PA, Shlipak MG: Long-term clinical consequences of acute kidney injury in the HIV-infected. Kidney Int 78: 478–485, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jose P, Skali H, Anavekar N, Tomson C, Krumholz HM, Rouleau JL, Moye L, Pfeffer MA, Solomon SD: Increase in creatinine and cardiovascular risk in patients with systolic dysfunction after myocardial infarction. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 2886–2891, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.James MT, Ghali WA, Knudtson ML, Ravani P, Tonelli M, Faris P, Pannu N, Manns BJ, Klarenbach SW, Hemmelgarn BR, Alberta Provincial Project for Outcome Assessment in Coronary Heart Disease (APPROACH) Investigators : Associations between acute kidney injury and cardiovascular and renal outcomes after coronary angiography. Circulation 123: 409–416, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldberg A, Kogan E, Hammerman H, Markiewicz W, Aronson D: The impact of transient and persistent acute kidney injury on long-term outcomes after acute myocardial infarction. Kidney Int 76: 900–906, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsagalis G, Akrivos T, Alevizaki M, Manios E, Stamatellopoulos K, Laggouranis A, Vemmos KN: Renal dysfunction in acute stroke: An independent predictor of long-term all combined vascular events and overall mortality. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 194–200, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cruz DN, Gheorghiade M, Palazzuoli A, Ronco C, Bagshaw SM: Epidemiology and outcome of the cardio-renal syndrome. Heart Fail Rev 16: 531–542, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hsu RK, McCulloch CE, Dudley RA, Lo LJ, Hsu CY: Temporal changes in incidence of dialysis-requiring AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 37–42, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mithani S, Kuskowski M, Slinin Y, Ishani A, McFalls E, Adabag S: Dose-dependent effect of statins on the incidence of acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 91: 520–525, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Afshinnia F, Straight A, Li Q, Slinin Y, Foley RN, Ishani A: Trends in dialysis modality for individuals with acute kidney injury. Ren Fail 31: 647–654, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Waikar SS, Curhan GC, Ayanian JZ, Chertow GM: Race and mortality after acute renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 2740–2748, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kelly KJ: Distant effects of experimental renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 1549–1558, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ratliff BB, Rabadi MM, Vasko R, Yasuda K, Goligorsky MS: Messengers without borders: mediators of systemic inflammatory response in AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 529–536, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grams ME, Rabb H: The distant organ effects of acute kidney injury. Kidney Int 81: 942–948, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]