Abstract

The type III RNAse, Dicer, is responsible for the processing of microRNA (miRNA) precursors into functional miRNA molecules, non-coding RNAs that bind to and target messenger RNAs for repression. Dicer expression is essential for mouse midbrain development and dopaminergic (DAergic) neuron maintenance and survival during the early post-natal period. However, the role of Dicer in adult mouse DAergic neuron maintenance and survival is unknown. To bridge this gap in knowledge, we selectively knocked-down Dicer expression in individual DAergic midbrain areas, including the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) via viral-mediated expression of Cre in adult floxed Dicer knock-in mice (Dicerflox/flox). Bilateral Dicer loss in the VTA resulted in progressive hyperactivity that was significantly reduced by the dopamine agonist, amphetamine. In contrast, decreased Dicer expression in the SNpc did not affect locomotor activity but did induce motor-learning impairment on an accelerating rotarod. Knock-down of Dicer in both midbrain regions of adult Dicerflox/flox mice resulted in preferential, progressive loss of DAergic neurons likely explaining motor behavior phenotypes. In addition, knock-down of Dicer in midbrain areas triggered neuronal death via apoptosis. Together, these data indicate that Dicer expression and, as a consequence, miRNA function, is essential for DAergic neuronal maintenance and survival in adult midbrain DAergic neuron brain areas.

Introduction

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small, non-coding RNAs that modulate mRNA expression (Cao et al., 2006, Bicker and Schratt, 2008, Fiore et al., 2008, Pietrzykowski et al., 2008, Huang and Li, 2009, Karr et al., 2009). miRNAs bind to miRNA-recognition elements (MRE), specific sequences usually located in target mRNA 3′-untranslated regions (UTRs) resulting in either mRNA cleavage (Bartel, 2004, Huppi et al., 2005, Martin and Caplen, 2006) or inhibition of translation (Ambros, 2004, Bartel, 2004, Zamore and Haley, 2005). In some cases, miRNAs have been shown to increase expression of their target genes (Vasudevan et al., 2007). miRNAs are derived from long primary transcripts that are sequentially processed by the ribonuclease, Drosha, and the type III RNAse, Dicer. While it is clear that miRNA expression and function is critical during CNS development (Davis et al., 2008, De Pietri Tonelli et al., 2008, Li et al., 2011, McLoughlin et al., 2012, Rosengauer et al., 2012) and neuronal maintenance and survival in some brain regions during post-natal periods (Schaefer et al., 2007), the role of miRNAs in the adult CNS is still largely unknown.

In the dopaminergic (DAergic) neuron-rich midbrain, a structure critical for voluntary locomotor processing and motivation (Salamone and Correa, 2012, Sulzer and Surmeier, 2013), miRNA expression is essential for midbrain formation during development and DAergic neuron differentiation. Wnt1-Cre-mediated conditional loss of Dicer in mice results in embryos with smaller midbrains compared to control embryos (Huang et al., 2010). In addition, Wnt1-Cre Dicer knock-out (KO) mice express DAergic precursor neurons that do not properly differentiate into DAergic neurons at E12.5. In cell culture, Dicer deletion in DAergic neurons derived from embryonic stem cells, triggers apoptosis and neuronal-like cell death (Kim et al., 2007). Finally, conditional knock-out of Dicer in dopamine transporter (DAT)-expressing neurons results in significant death of midbrain DAergic neurons in mice by three weeks of age. However, whether expression of Dicer dependent miRNAs is critical for maintenance and survival of adult midbrain DAergic neuron areas is unknown. We sought to test the hypothesis that Dicer expression, and by extension miRNAs, are critical for DAergic neuron maintenance and survival even in adult animals. To do this, we knocked-out Dicer expression in mice homozygous for a floxed Dicer allele (Dicerflox/flox) allowing for conditional knock-out of Dicer in neuronal populations that express Cre (Harfe et al., 2005). However, to induce Dicer deletion in discreet midbrain areas during adulthood, we delivered Cre into the VTA and SNpc using adeno-associated virus (AAV)- mediated gene delivery.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Dicerflox/flox mice, which contain loxP sites on either side of exon 23 of the Dicer1 (Dicer1, Dcr-1 homolog (Drosophila)) gene, were purchased from Jackson Laboratories and bred in our animal facilities. Breeding was conducted by mating heterozygous pairs. The mice were group housed four mice/cage on a 12-h light-dark cycle and given food and water ad libitum. Male mice were used for all experiments. Mice were at least 8 weeks old at the beginning of each experiment. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines for care and use of laboratory animals provided by the National Research Council (National Research Council, 1996), as well as with an approved animal protocol from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Massachusetts Medical School.

Virus microinjection

AAV2-CMV-PI-Cre-ZsGreen and AAV2-eGFP virus particles were provided by the viral vector core facility of the University of Massachusetts Medical School. Dicerflox/flox mice were anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) (VEDCO). The surgical area was shaved and disinfected. Mice were placed in a stereotaxic frame (Stoelting Co.) with mouse adaptor and a small incision was cut in the scalp to expose the skull. Using bregma and lambda as landmarks, the skull was leveled in the coronal and sagittal planes. AAV2-Cre-ZsGreen or AAV2-eGFP was injected into either VTA or SNpc. For the VTA, the coordinates were: anterior-posterior (AP), −3.3 mm from bregma; medial-lateral (ML), ±0.5 mm from midline; dorsal-ventral (DV), −4.0 mm from brain surface. For the SNpc, the coordinates were: AP, −3.0 mm from bregma; ML, ±1.5 mm from midline; DV, −4.0 mm from brain surface. The virus (1 × 1012 viral particles/ml, 0.5 μl/side) was injected at a flow rate of 0.1 μl/min. The injection needle remained in place for 5 min post-injection before slowly being withdrawn.

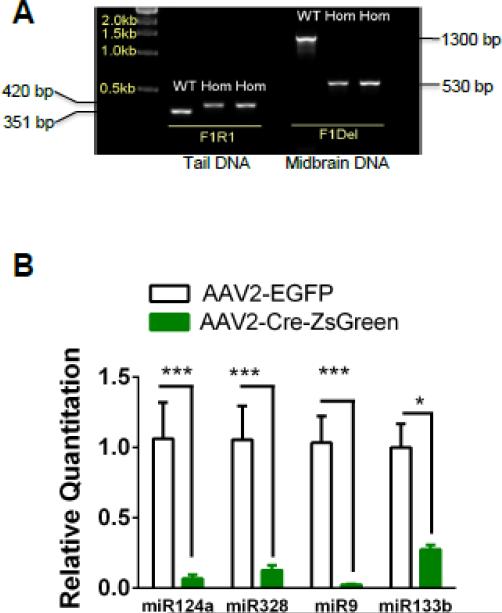

Genotyping

As described previously (Harfe et al., 2005), two sets of primers were used to verify the insertion of the loxP site and the deletion of the Dicer gene. The conditional floxed allele was genotyped using primers DicerF1 (5′-CCTGACAGTGACGGTCCAAAG-3′) and DicerR1 (5′-CATGACTCTTCAACTCAAACT-3′), which amplify a DNA fragment that is 351 bp in wild-type (WT) mice, and 420 bp in Dicerflox/flox (Figure 1). Four weeks after the AAV2-Cre-ZsGreen virus infection, brain tissue was laser captured (described below). Total DNA was extracted with a tissue DNA extraction kit (DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit, Qiagen). The deletion allele was genotyped using primers DicerF1 and DicerDel (5′-CCTGAGCAAGGCAAGTCATTC-3′). The band for the deleted allele is 471 bp whereas the band for a WT allele is 1,300 bp (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Verification of conditional Dicer knock-out. A. DNA agarose gel illustrating amplified DNA fragments from genomic DNA of WT and homozygous Dicerflox/flox mice using Dicer F1 and Dicer R1 primers (left). Right, amplified fragments from midbrain DNA of WT and Dicerflox/flox infected with AAV2-Cre-ZsGreen using the Dicer F1 and Dicer Del primers. B. Midbrain miRNA expression from Dicerflox/flox mice infected with AAV2-eGFP (white bars) or AAV2-Cre-ZsGreen (green bars). *p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001, Student's t-test (n =3 mice/treatment).

Laser capture microdissection

Eight weeks after virus infection, mice were sacrificed and the brains were removed, snap-frozen in dry ice-cooled 2-methylbutane (−60°C) and stored at −80°C. Coronal serial sections (10 μm) were cut using a cryostat (Leica Microsystems Inc.) and mounted on pre-cleaned glass slides (Fisher Scientific). The sections were immediately placed in a slide box on dry ice until completion of sectioning followed by storage at −80°C. Frozen sections were allowed to thaw for 30 s and then immediately fixed in cold acetone for 4 min. The slides were washed twice in PBS (prepared in DEPC water) and subsequently dehydrated in a graded ethanol series (for 30 s each in 70% ethanol, 95% ethanol, 100% ethanol, and once for 5 min in xylene). Slides were allowed to dry for 5 min. All ethanol solutions and xylene were prepared fresh to preserve RNA integrity. The Veritas Microdissection System Model 704 (Arcturus Bioscience) was used for laser capture microdissection (LCM). ZsGreen- or EGFP-positive neurons were captured on CapSure Macro LCM caps (Arcturus Bioscience) for total RNA isolation.

Real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from individual replicate samples using a Micro Scale RNA Isolation Kit (Ambion). miRs were amplified from laser-captured material except for miR-133b which was amplified from tissue punches of infected areas due to low yield. RNA samples extracted from ZsGreen- or eGFP-positive neurons were reverse-transcribed into cDNA using a miRNA TaqMan Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems). Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using an Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time System and miRNA TaqMan assays (Applied Biosystems). Samples containing no reverse transcriptase were used as negative controls. Relative gene expression differences between eGFP-positive neurons and ZsGreen-positive neurons were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method. Expression values were normalized to expression of sno202, a small nucleolar RNA not produced by Dicer (Politz et al., 2009, Brattelid et al., 2011). Samples were analyzed in triplicate. Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis.

Immunohistochemistry

Eight weeks after virus infection, mice were sacrificed and the brains removed to make coronal serial sections (10 μm) and mounted onto pre-cleaned glass slides. Immunolabeling was done as previously described (Zhao-Shea et al., 2011). Briefly, the sections were immediately placed in a slide box on dry ice until completion of sectioning followed by storage at −80°C. The frozen sections were thawed for 30 s and fixed in 4 % paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). The slides were rinsed in PBS twice for 5 min, and treated with 0.2 % Trition X-100 PBS (PBST) for 5 min followed by incubation in 2 % BSA/PBS for 30 min. Sections were washed with PBS once and then incubated in primary antibodies directed to tyrosine hydroxylase (TH, monoclonal, 1:250 dilution, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) in 2 % BSA/PBS overnight at 4°C. The sections were washed with PBS three times for 5 min followed by incubation in secondary fluorescent labeled (goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 594, 1:300 dilutions, Invitrogen) at room temperature in the dark for 30 min. For NeuN and TH double labeling, the sections were washed with PBS and incubated with primary antibodies NeuN (monolclonal, 1:100 dilution, Millipore) and TH (polyclonal, 1:1000 dilution, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) overnight at 4°C. After PBS washing, the secondary antibodies (goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 594 and goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488, 1:300 dilutions, Invitrogen) were incubated at room temperature in the dark for 30 min. After washing with PBS 5 times for 5 min/wash, sections were covered with cover slides using VECTASHIELD® Mounting Medium (Vector laboratories, Inc.). Neurons were counted as signal-positive if intensities were at least 2 times higher than that of the average value of background (sections stained without primary antibodies).

TUNEL staining

Frozen sections were made as described above at different time points (2 weeks, 4 weeks, 6 weeks and 8 weeks) after virus infection. The TUNEL assay (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Locomoter activity

Locomotor activity was recorded using an automated system (San Diego Instruments, La Jolla, CA, USA) with photobeams, which recorded ambulation (consecutive beam breaks). Before virus microinjection, mice were placed individually in a novel cage and recorded for 90 min for their baseline locomotor activity. At different time points after the virus infection (4 weeks, 6 weeks, and 8 weeks), locomotor activity was recorded in a novel cage. For amphetamine treatment, mice were placed in a novel cage and activity was recorded for 20 min, followed by an i.p. injection of amphetamine (0.5 mg/kg) or saline. Activity post-injection was recorded for 3 h.

Rotarod test

A rotarod apparatus (San Diego Instruments, San Diego, CA) was used to evaluate motor coordination and balance. Mice were placed on an accelerating rod (4 to 40 rpm) over a period of 300 s. Any mice remaining on the apparatus after 300 s were removed and the rotor rod time scored as 300. The length of time that the mouse remained on the rod (latency to fall) was recorded. Each mouse underwent seven consecutive trials with 10 min intervals between trials.

At the end of each behavioral experiment, brains of mice were isolated, sliced, and stained to verify infection site and loss of DAergic neurons as described above. Mice that were mis-injected were subsequently removed from behavioral analysis.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using 1- or 2-way ANOVAs as indicated followed by Bonferroni post-hoc tests. Data were analyzed using GraphPad software. Student's t tests were used to analyze fold expression of qRT-PCR data and immunohistochemistry data. Results were considered significant at p < 0.05. All data are expressed as the mean ± SEM.

Results

To test the hypothesis that Dicer expression is critical for maintenance and survival of DAergic neurons in adult midbrain areas, we selectively expressed Cre recombinase in either the VTA or SNpc of adult (>8 week old) Dicerflox/flox mice. To do this, recombinant adeno-associated virus serotype 2 (AAV2) co-expressing Cre under the control of the CMV promotor and the green fluorescent marker, ZsGreen under the control of the β-actin promotor, were injected into VTA or SNpc. Control mice received AAV2 encoding enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) alone. To verify loss of Dicer expression, 4-6 weeks post AAV2 injection, midbrain areas expressing Cre, identified by expression of ZsGreen under fluorescence microscopy, were isolated and genotyped. Deletion of the floxed NEO-cassette was verified by PCR using primers spanning the floxed region (Fig. 1A). To verify loss of miRNA expression, infected areas were laser dissected followed by isolation of small RNAs and quantitation using qRT-PCR. Expression of Cre in midbrain of Dicerflox/flox mice resulted in statistically significant reduction of common neuronal miRNAs including miR-124a, -328, -9, and -133b (Fig. 1B).

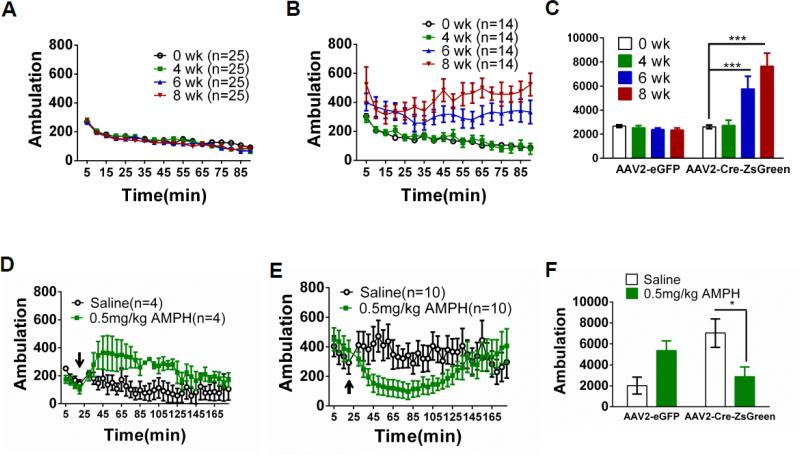

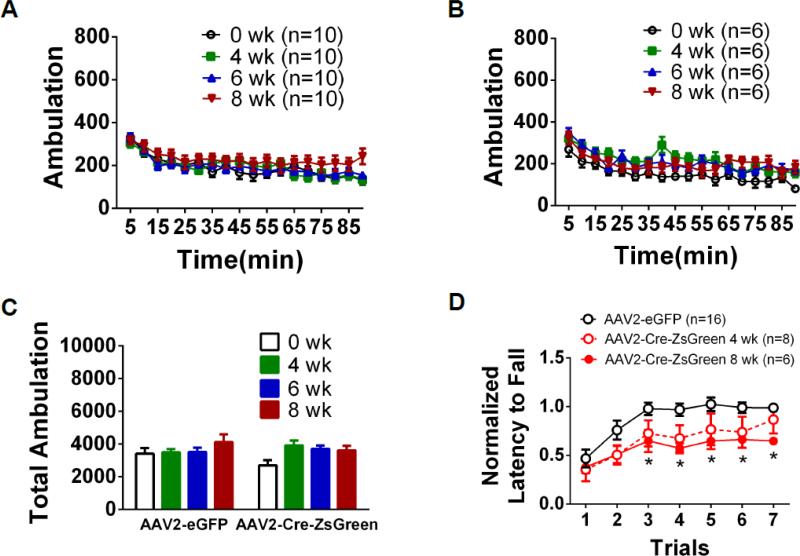

To determine the effect of Dicer deletion in the VTA on behavior, Dicerflox/flox mice were infected with AAV2-eGFP (control) or AAV2-Cre-ZsGreen in the VTA, bilaterally. Locomotor activity was monitored weekly 4-8 weeks post infection. In control animals, locomotor activity 4-8 weeks after infection did not differ from baseline (activity measured prior to infection, Fig. 2A, C). In contrast, locomotor activity in AAV2-Cre-ZsGreen-infected animals progressively increased from 6-8 weeks post-infection (Fig. 2B, C). Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of virus (F1, 140 = 58.7, p < 0.001) and time (F3, 140 = 16.3, p < 0.001) and significant time x virus interaction (F3, 140 = 20.3, p < 0.001). Post-hoc analysis indicated a statistically significant increase in locomotor activity six and eight weeks post-infection for AAV2-Cre-ZsGreen (p < 0.001), but not AAV2-eGFP infected mice. To determine the role of DA in hyperactivity elicited by reduced Dicer expression in the VTA, we injected control and hyperactive VTA Cre-expressing Dicerflox/flox mice with the DA agonist, amphetamine (Fig. 2D, E, F). Two-way ANOVA indicated a significant drug treatment and virus interaction (F1, 23 = 7.52, p < 0.05). Control animals responded to amphetamine with increased locomotor activity compared to a saline injection (Fig. 2D, F). Interestingly, hyperactivity in VTA Cre-expressing animals was paradoxically reduced in response to amphetamine similar to what is seen in models of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (p < 0.05, Fig. 2E, F)(Gong et al., 2011, Won et al., 2011).

Figure 2.

Dicer loss in adult VTA elicits locomotor hyperactivity. A. Ambulation in Dicerflox/flox mice infected with AAV2-eGFP in the VTA. Ambulation at baseline (prior to injection) and 4, 6, and 8 weeks (wk) post-infection over 90 min are shown. Each data point represents summed ambulation during 5 min intervals (the VTA was correctly targeted in 25/26 mice). B. Ambulation in Dicerflox/flox mice infected with AAV2-Cre-ZsGreen in the VTA. Ambulation at baseline and 4, 6, and 8 weeks post-infection are shown (the VTA was correctly targeted in 14/16 mice). C. Summed total ambulation over 90 min in each group at each time point post-infection. D. Ambulatory response to saline (i.p., open circles) or 0.5 mg/kg amphetamine (AMPH, i.p., green squares) in Dicerflox/flox mice expressing eGFP in VTA (the VTA was correctly targeted in 4/4 mice). Time of injection is indicated by the arrow. E. Ambulatory response to saline or AMPH in Dicerflox/flox mice expressing Cre in VTA (the VTA was correctly targeted in 10/12 mice). F. Summed total ambulation over 90 min post-saline or -AMPH injection in each group. Two-way ANOVA, Bonferroni post-hoc, * p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001.

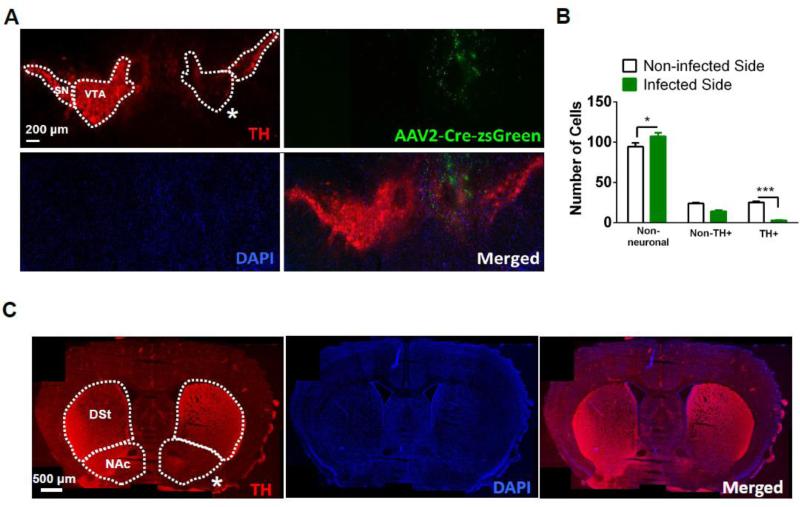

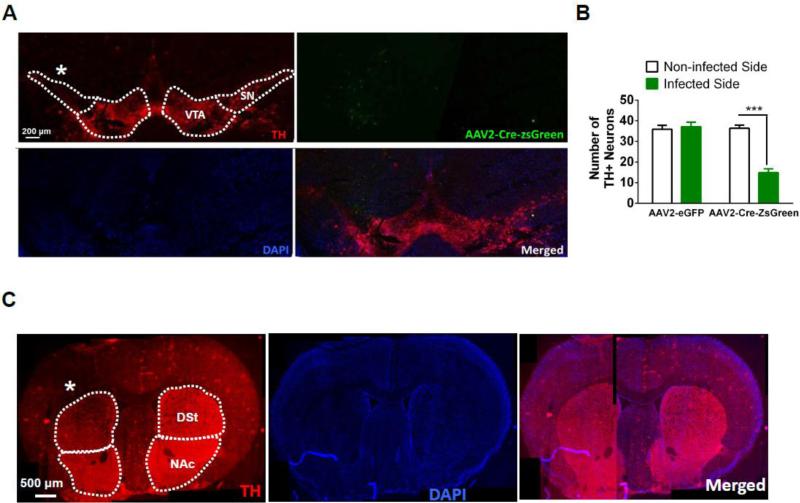

To test the hypothesis that reduction of Dicer expression was necessary for VTA DAergic neuron maintenance and survival, Dicerflox/flox mice were injected with AAV2-Cre-ZsGreen unilaterally into the VTA. Six weeks post-infection, brains were harvested, sliced, and labeled with the nuclear stain, DAPI, the neuronal specific nuclear stain, NeuN, and the TH antibody allowing for detection of total cells, total neurons, and DAergic neurons, respectively, in infected and control midbrain regions. The number of non-neuronal cells (DAPI positive, NeuN negative), DAergic (TH immunopositive), and non-DAergic neurons (NeuN positive, TH immunonegative) in the VTA were counted and compared to the non-infected side 6 weeks after injection (Fig. 3A, B). Two-way ANOVA indicated a significant effect of virus infection (F1, 12 = 7.93, p < 0.05), cell type (F2, 12 = 623.6, p < 0.001), and a significant virus x cell type interaction (F2,12 = 20.6, p<0.001). Post-hoc analysis revealed that reduction of Dicer expression significantly reduced the number of TH immunopositive neurons within the VTA compared to the non-infected side (Fig. 3B, p < 0.001) while increasing the number of non-neuronal cells (p<0.05), presumably glia which proliferate or migrate to the lesioned area (Maia et al., 2012). Although there was a trend for decreased non-TH immunopositive neurons with reduced Dicer expression compared to control, it was not statistically significant. In addition, TH staining was dramatically reduced in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) indicating loss of DAergic neuron terminals (Fig. 3C). Reduction of TH staining was localized to the NAc; whereas dorsal striatum (DSt) was relatively unaffected consistent with loss of DAergic neurons specifically in the VTA. To further control for the specificity of our viral-mediated approach, we unilaterally infected the VTA of Dicerflox/flox mice with AAV2-eGFP and unilaterally infected the VTA of WT mice (Dicerwt/wt) with AAV2-Cre-ZsGreen. The number of VTA DAergic neurons in the infected sides of both sets of control mice did not significantly differ compared to the number of VTA DAergic neurons in the non-infected sides (Fig. 4A).

Figure 3.

Dicer expression is necessary for DAergic neuron survival in the adult VTA. A. Representative photomicrograph from a Dicerflox/flox mouse infected with AAV2-Cre-ZsGreen unilaterally. Dicer loss leads to significant reduction of TH immunopositive neurons (stained red, top left panel) on the infected side (indicated by the white asterisk). Photomicrograph of virus infected area (green, top right panel) is shown. DAPI-labeled cells are depicted in blue (bottom left panel). Merged image is illustrated in the bottom right panel. B. Average total number of non-neuronal cells, TH-immunonegative (non-TH+) neurons and TH-immunopositive (TH+) neurons in the VTA of AAV2-Cre-ZsGreen-infected (infected compare to the non-infected side). Cell counts were calculated 8 weeks after virus injection (n = 15-42 slices from 3 mice/treatment). C. Representative photomicrograph illustrating loss of TH expression in the NAc. Twoway ANOVA, Bonferroni post-hoc, *p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001.

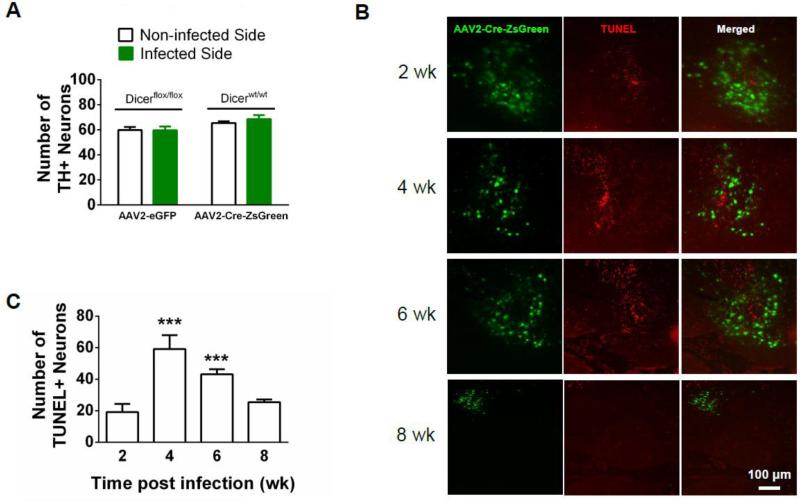

Figure 4.

Loss of adult VTA DAergic neurons with reduced Dicer expression is specific and triggered by apoptosis. A. Averaged sum of TH immunopositive VTA neurons in Dicerflox/flox mice infected with AAV2-eGFP and Dicerwt/wt mice infected with AAV2-Cre-ZsGreen. TH immunopositive neurons are compared between the infected and control, non-infected side. B. Representative photomicrographs illustrating AAV2-Cre-ZsGreen expression in the VTA (green, left), TUNEL stained neurons (red, middle) and merged images (right) at different time points after virus injection in Dicerflox/flox mice. C. Number of TUNEL-positive neurons in infected Dicerflox/flox mice at different time points. One-way ANOVA, Bonferroni post-hoc, *** p < 0.001.

To determine if reducing Dicer expression induced apoptosis as the mechanism of cell death in DAergic neurons within the VTA, we infected the VTA of a cohort of Dicerflox/flox mice with AAV2-Cre-ZsGreen and performed TUNEL staining at various time points post-infection including 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks (Fig. 4B, C). One-way ANOVA indicated a main effect of time on TUNEL-positive cells (F4, 32 = 49.6, p < 0.001, Fig. 4C). Post-hoc analysis revealed a significant increase in neurons undergoing apoptosis at four and six weeks post-infection compared to two weeks post-infection (p < 0.001). Thus, TUNEL staining was detected as early as two weeks post-infection, but peaked at 4 weeks indicating reduced Dicer expression triggers apoptosis in adult VTA. Interestingly, the majority of TUNEL stained nuclei within the infected area did not co-localize with Zs-Green expression. As TUNEL stained slices are processed at fixed time intervals, this is likely due to loss of Zs-Green expression in dying/dead neurons or diffusion of fluorophore in apoptotic neurons with compromised membrane integrity.

To determine the effect of Dicer deletion in SNpc, adult Dicerflox/flox mice were infected with AAV2-Cre-ZsGreen bilaterally in SNpc. Locomotor activity was monitored weekly post-infection (Fig. 5). Locomotor activity was not affected by reduced Dicer expression in the SNpc as locomotor activity did not differ from baseline up to 8 weeks post-Cre expression (Fig. 5A, B, C). Because DA is critical for motor coordination learning in addition to voluntary movement (Beeler et al., 2010), we compared rotarod performance of AAV2-Cre-ZsGreen-infected animals at 4- and 8-weeks post-infection to control-infected animals (Fig. 5D). Two-way ANOVA indicated a significant main effect of trial (F6, 162 = 13.3, p < 0.001) and virus (F2, 27 = 5.05, p < 0.05) bot not a significant interaction. Over seven successive trials on the accelerating rotarod, control mice significantly increased their latency to fall of the apparatus indicating motor coordination learning. Post-hoc analysis revealed that AAV2-Cre-ZsGreen-infected animals exhibited poorer performance at 8- but not 4-weeks post-infection, compared to controls as reflected in decreased latency to fall on trials 3-7 compared to AAV2-eGFP infected mice (p<0.05). As with the VTA, the number of TH immunopositive neurons in the SNpc of AAV2-Cre-ZsGreen-infected animals was significantly reduced compared to control indicating Dicer expression is necessary for DAergic neuron survival in adult animals (Fig. 6A, B). This was also confirmed by decreased TH labeling in DSt of infected animals (Fig. 6C).

Figure 5.

Loss of Dicer expression in SNpc impairs motor-learning. Ambulation in Dicerflox/flox mice infected with (A) AAV2-eGFP or (B) AAV2-Cre-ZsGreen in the SNpc at baseline (prior to injection) and 4, 6, and 8 weeks post-infection over 90 min are shown (the SNpc was correctly targeted in A) 10/10 and 6/7 mice, respectively). C. Summed total ambulation from (A) and (B). D. Normalized latency to fall off an accelerating rotarod on 7 consecutive trials in Dicerflox/flox mice infected with AAV2-eGFP or AAV2-Cre-ZsGreen (4- or 8-weeks post-infection) in the SNpc. Each trial was normalized to the average latency of trials 5-7 in control, AAV2-eGFP-infected animals (i.e. when rotarod performance reached a stable baseline). Two-way ANOVA, Bonferroni Post-hoc, * p < 0.05.

Figure 6.

Dicer expression is necessary for DAergic neuron survival in the adult SNpc. A. Representative photomicrographs illustrating TH expression (red, top left panel), AAV2-Cre-ZsGreen-infected area (green, top right panel), DAPI staining (blue, bottom left panel) and merged signals (bottom right panel). The infected side is denoted by a white asterisk. B. Average total number of TH-immunopositive neurons in the SNpc of AAV2-eGFP (control) and AAV2-Cre-ZsGreen infected mice. Neurons were quantified 8 weeks after virus injection (n = 18-20 slices from 4 mice/treatment). C. Representative photomicrograph illustrating loss of TH expression in the DSt.

Discussion

Here we show that Dicer expression is critical for survival and maintenance of adult DAergic midbrain neurons in C57BL/6J mice. Genetic deletion of Dicer specifically in midbrain elicited a progressive loss of both VTA and SNpc DAergic neurons through an apoptotic mechanism. The present data extend previous studies (Kim et al., 2007) and indicate that Dicer expression is necessary for survival of DAergic neurons even in adulthood. The progressive loss of DAergic neurons over time in the VTA resulted in hyperactivity and this hyperactivity was, paradoxically, reduced by amphetamine. These data are consistent with previous VTA lesioning studies in rats, which also induced amphetamine-sensitive hyperactivity (Galey et al., 1977, Le Moal et al., 1977, Stinus et al., 1977). Interestingly, Dicer loss in SNpc did not affect locomotor activity but did impair rotarod performance cogent with prior work implicating a role for striatal DA in acquisition of motor learning (Beeler et al., 2010). Our results also support recent data indicating that, at least in mice, skilled motor learning is more sensitive to the effects of partial DAergic neuron depletion compared to simple motor activity (Chagniel et al., 2012).

A previous study examined Dicer deletion under control of the DAT promoter and found that animals that develop without Dicer expression in DAT-expressing neurons exhibit significant loss of neurons by three weeks of age and a 90 % loss by 8 weeks (Kim et al., 2007). Neuronal loss occurred via apoptosis. Similarly, our study indicates knockout of Dicer in adult DAergic neuron-rich midbrain areas also induces apoptosis. Apoptosis peaked 4 weeks post-infection returning to baseline after 8 weeks matching the progressive severity of the measured motor behavioral phenotype in these animals and also mirroring the peak time of Cre-expression using AAV2-mediated gene delivery.

The criticality of Dicer expression and Dicer-processed miRNA function in the CNS differs between brain regions, is developmentally-dependent, and depends on neuronal sub-type. For example, genetic deletion of Dicer in cells that express calmodulin kinase II (CAMKII), a marker for glutamatergic neurons in cortex and hippocampus, has different phenotypes in mice depending on the developmental period when the deletion occurs. Crossing Dicerflox/flox mice with a-R1AG-5 CAMKII-Cre mice results in Dicer deletion at embryonic day 15.5 (e15.5) (Davis et al., 2008). The resulting phenotype included microcephaly, significant increase in early post-natal apoptosis, and death by 20 days of age. Deleting Dicer in CamKII-expressing neurons beginning at P18 using a different Cre line also induces neurodegeneration with abnormal tau hyperphosphorylation (Hebert et al., 2010). In contrast, inducing Dicer deletion in CaMKII-expressing neurons during adulthood using a tamoxifen-inducible promoter enhances learning and memory in mice without dramatic neurodegeration for up to 14 weeks post-deletion (Konopka et al., 2010). Similarly, Dicer deletion in adult amygdala or in striatal dopaminoceptive medium spiny neurons does not induce apoptosis or neurodegeneration in these brain areas (Cuellar et al., 2008, Haramati et al., 2011). Interestingly, deletion of Dicer in Purkinje neurons of the cerebellum elicits a relatively slow neurodegenerative process whereby these neurons appear normal up to 10 weeks of age but begin to degenerate over the next several weeks of life (Schaefer et al., 2007). In contrast, our data indicate that in the absence of Dicer expression, DAergic neurons degenerate rapidly; whereas non-DAergic (presumably GABAergic) neurons within the VTA were more resistant to cell death similar to striatal medium spiny neurons and Purkinje neurons which are also GABAergic (Schaefer et al., 2007, Cuellar et al., 2008).

Interestingly, Kim et. al. identified a specific miRNA, miR-133b, that is enriched in DAergic neurons and depleted in Parkinson's disease brains, regulates DAergic neuron differentiation (Kim et al., 2007). While the precise role of miRNA-133b in DAergic neuron maintenance is unclear (Heyer et al., 2012), it raises the intriguing possibility that a specific set of miRNAs may be critical for DAergic neuron integrity throughout their lifespan. Identification of miRNAs integral for DAergic neuron health could lead to new strategies for treatment of DAergic neuron degenerative diseases such as Parkinson's disease.

In summary, our data indicate that Dicer expression and Dicer-dependent miRNAs appear to be necessary for adult DAergic neuron maintenance and survival. Combined with previous studies, Dicer expression is critical for DAergic neuron integrity from early post-natal periods throughout adulthood.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Institute on Neurological Disorders and Stroke award number 1R01NS059586 (ART) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse award numbers 1R21DA031952 (ART and PDG) and 1R21DA033543 (PDG). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ambros V. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature. 2004;431:350–355. doi: 10.1038/nature02871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeler JA, Cao ZF, Kheirbek MA, Ding Y, Koranda J, Murakami M, Kang UJ, Zhuang X. Dopamine-dependent motor learning: insight into levodopa's long-duration response. Annals of neurology. 2010;67:639–647. doi: 10.1002/ana.21947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bicker S, Schratt G. microRNAs: tiny regulators of synapse function in development and disease. J Cell Mol Med. 2008;12:1466–1476. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00400.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brattelid T, Aarnes EK, Helgeland E, Guvaag S, Eichele H, Jonassen AK. Normalization strategy is critical for the outcome of miRNA expression analyses in the rat heart. Physiological genomics. 2011;43:604–610. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00131.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Yeo G, Muotri AR, Kuwabara t, Gage FH. Noncoding RNAs in the mammalian central nervous system. Ann Rev Neurosci. 2006;29:77–103. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.112839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chagniel L, Robitaille C, Lacharite-Mueller C, Bureau G, Cyr M. Partial dopamine depletion in MPTP-treated mice differentially altered motor skill learning and action control. Behav Brain Res. 2012;228:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuellar TL, Davis TH, Nelson PT, Loeb GB, Harfe BD, Ullian E, McManus MT. Dicer loss in striatal neurons produces behavioral and neuroanatomical phenotypes in the absence of neurodegeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:5614–5619. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801689105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis TH, Cuellar TL, Koch SM, Barker AJ, Harfe BD, McManus MT, Ullian EM. Conditional loss of Dicer disrupts cellular and tissue morphogenesis in the cortex and hippocampus. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2008;28:4322–4330. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4815-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Pietri Tonelli D, Pulvers JN, Haffner C, Murchison EP, Hannon GJ, Huttner WB. miRNAs are essential for survival and differentiation of newborn neurons but not for expansion of neural progenitors during early neurogenesis in the mouse embryonic neocortex. Development. 2008;135:3911–3921. doi: 10.1242/dev.025080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore R, Siegel G, Schratt G. MicroRNA function in neuronal development, plasticity and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1779:471–478. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galey D, Simon H, Le Moal M. Behavioral effects of lesions in the A10 dopaminergic area of the rat. Brain research. 1977;124:83–97. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90865-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong R, Ding C, Hu J, Lu Y, Liu F, Mann E, Xu F, Cohen MB, Luo M. Role for the membrane receptor guanylyl cyclase-C in attention deficiency and hyperactive behavior. Science. 2011;333:1642–1646. doi: 10.1126/science.1207675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haramati S, Navon I, Issler O, Ezra-Nevo G, Gil S, Zwang R, Hornstein E, Chen A. MicroRNA as repressors of stress-induced anxiety: the case of amygdalar miR-34. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2011;31:14191–14203. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1673-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harfe BD, McManus MT, Mansfield JH, Hornstein E, Tabin CJ. The RNaseIII enzyme Dicer is required for morphogenesis but not patterning of the vertebrate limb. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:10898–10903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504834102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert SS, Papadopoulou AS, Smith P, Galas MC, Planel E, Silahtaroglu AN, Sergeant N, Buee L, De Strooper B. Genetic ablation of Dicer in adult forebrain neurons results in abnormal tau hyperphosphorylation and neurodegeneration. Human molecular genetics. 2010;19:3959–3969. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyer MP, Pani AK, Smeyne RJ, Kenny PJ, Feng G. Normal midbrain dopaminergic neuron development and function in miR-133b mutant mice. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2012;32:10887–10894. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1732-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang T, Liu Y, Huang M, Zhao X, Cheng L. Wnt1-cre-mediated conditional loss of Dicer results in malformation of the midbrain and cerebellum and failure of neural crest and dopaminergic differentiation in mice. Journal of molecular cell biology. 2010;2:152–163. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjq008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W, Li MD. Differential allelic expression of dopamine D1 receptor gene (DRD1) is modulated by microRNA miR-504. Biol Psych. 2009;65:702–705. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huppi K, Martin SE, Caplen NJ. Defining and assaying RNAi in mammalian cells. Molecular Cell. 2005;17:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karr J, Vagin V, Chen K, Ganesan S, Olenkina O, Gvozdev V, Featherstone DE. Regulation of glutamate receptor subunit availability by microRNAs. J Cell Biol. 2009;185:685–697. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200902062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Inoue K, Ishii J, Vanti WB, Voronov SV, Murchison E, Hannon G, Abeliovich A. A MicroRNA feedback circuit in midbrain dopamine neurons. Science. 2007;317:1220–1224. doi: 10.1126/science.1140481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konopka W, Kiryk A, Novak M, Herwerth M, Parkitna JR, Wawrzyniak M, Kowarsch A, Michaluk P, Dzwonek J, Arnsperger T, Wilczynski G, Merkenschlager M, Theis FJ, Kohr G, Kaczmarek L, Schutz G. MicroRNA loss enhances learning and memory in mice. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2010;30:14835–14842. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3030-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Moal M, Stinus L, Simon H, Tassin JP, Thierry AM, Blanc G, Glowinski J, Cardo B. Behavioral effects of a lesion in the ventral mesencephalic tegmentum: evidence for involvement of A10 dopaminergic neurons. Advances in biochemical psychopharmacology. 1977;16:237–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Bian S, Hong J, Kawase-Koga Y, Zhu E, Zheng Y, Yang L, Sun T. Timing specific requirement of microRNA function is essential for embryonic and postnatal hippocampal development. PloS one. 2011;6:e26000. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maia S, Arlicot N, Vierron E, Bodard S, Vergote J, Guilloteau D, Chalon S. Longitudinal and parallel monitoring of neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration in a 6-hydroxydopamine rat model of Parkinson's disease. Synapse. 2012;66:573–583. doi: 10.1002/syn.21543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SE, Caplen NJ. Mismatched siRNAs downregulate mRNAs as a function of target site location. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:3694–3698. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoughlin HS, Fineberg SK, Ghosh LL, Tecedor L, Davidson BL. Dicer is required for proliferation, viability, migration and differentiation in corticoneurogenesis. Neuroscience. 2012;223:285–295. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzykowski AZ, Friesen RM, Martin GE, Puig SI, Nowak CL, Wynne PM, Siegelmann HT, Treistman SN. Posttranscriptional regulation of BK channel splice variant stability by miR-9 underlies neuroadaptation to alcohol. Neuron. 2008;59:274–287. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Politz JC, Hogan EM, Pederson T. MicroRNAs with a nucleolar location. Rna. 2009;15:1705–1715. doi: 10.1261/rna.1470409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosengauer E, Hartwich H, Hartmann AM, Rudnicki A, Satheesh SV, Avraham KB, Nothwang HG. Egr2::cre mediated conditional ablation of dicer disrupts histogenesis of Mammalian central auditory nuclei. PloS one. 2012;7:e49503. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salamone JD, Correa M. The mysterious motivational functions of mesolimbic dopamine. Neuron. 2012;76:470–485. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer A, O'Carroll D, Tan CL, Hillman D, Sugimori M, Llinas R, Greengard P. Cerebellar neurodegeneration in the absence of microRNAs. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2007;204:1553–1558. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinus L, Gaffori O, Simon H, Le Moal M. Small doses of apomorphine and chronic administration of d-amphetamine reduce locomotor hyperactivity produced by radiofrequency lesions of dopaminergic A10 neurons area. Biological psychiatry. 1977;12:719–732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulzer D, Surmeier DJ. Neuronal vulnerability, pathogenesis, and Parkinson's disease. Movement disorders : official journal of the Movement Disorder Society. 2013;28:41–50. doi: 10.1002/mds.25095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevan S, Tong Y, Steitz JA. Switching from repression to activation: microRNAs can up-regulate translation. Science. 2007;318:1931–1934. doi: 10.1126/science.1149460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Won H, Mah W, Kim E, Kim JW, Hahm EK, Kim MH, Cho S, Kim J, Jang H, Cho SC, Kim BN, Shin MS, Seo J, Jeong J, Choi SY, Kim D, Kang C, Kim E. GIT1 is associated with ADHD in humans and ADHD-like behaviors in mice. Nature medicine. 2011;17:566–572. doi: 10.1038/nm.2330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamore PD, Haley B. Ribo-gnome: the big world of small RNAs. Science. 2005;309:1519–1524. doi: 10.1126/science.1111444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao-Shea R, Liu L, Soll LG, Improgo MR, Meyers EE, McIntosh JM, Grady SR, Marks MJ, Gardner PD, Tapper AR. Nicotine-mediated activation of dopaminergic neurons in distinct regions of the ventral tegmental area. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:1021–1032. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]