Abstract

Chronic neuropathic pain is often refractory to current pharmacotherapies. The rodent Mas-related G-protein-coupled receptor subtype C (MrgC) shares substantial homogeneity with its human homolog, MrgX1, and is located specifically in small-diameter dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons. However, evidence regarding the role of MrgC in chronic pain conditions has been disparate and inconsistent. Accordingly, the therapeutic value of MrgX1 as a target for pain treatment in humans remains uncertain. Here, we found that intrathecal injection of BAM8-22 (a 15-amino acid peptide MrgC agonist) and JHU58 (a novel dipeptide MrgC agonist) inhibited both mechanical and heat hypersensitivity in rats after an L5 spinal nerve ligation (SNL). Intrathecal JHU58-induced pain inhibition was dose-dependent in SNL rats. Importantly, drug efficacy was lost in Mrg-cluster gene knockout (Mrg KO) mice and was blocked by gene silencing with intrathecal MrgC siRNA and by a selective MrgC receptor antagonist in SNL rats, suggesting that the drug action is MrgC-dependent. Further, in a mouse model of trigeminal neuropathic pain, microinjection of JHU58 into ipsilateral subnucleus caudalis inhibited mechanical hypersensitivity in wild-type but not Mrg KO mice. Finally, JHU58 attenuated the mEPSC frequency both in medullary dorsal horn neurons of mice after trigeminal nerve injury and in lumbar spinal dorsal horn of mice after SNL. We provide multiple lines of evidence that MrgC agonism at spinal but not peripheral sites may constitute a novel pain inhibitory mechanism that involves inhibition of peripheral excitatory inputs onto postsynaptic dorsal horn neurons in different rodent models of neuropathic pain.

Keywords: MrgC, dorsal root ganglion, spinal cord, neuropathic pain, analgesia

1. Introduction

Chronic neuropathic pain is challenging to treat and often refractory to current pharmacotherapies [3,42,43]. Because the major analgesics (eg, opioids) bind to receptors that are widely expressed throughout the central nervous system, dose-limiting adverse effects and perceived risks of addiction and abuse present substantial barriers to their clinical use [42]. Hence, recent efforts have focused on identifying novel molecular targets on nociceptive sensory neurons in trigeminal and dorsal root ganglia (DRG). Such targets may offer an opportunity for pain-selective pharmacologic interventions [1,9].

Mas-related G-protein-coupled receptors (Mrg) may play an important role in pain sensation [18,33]. Of the rodent Mrgs (A-D), MrgC (mouse MrgC11 and rat homolog rMrgC) is expressed specifically in small-diameter afferent neurons, which are presumably nociceptive. MrgC shares substantial homogeneity with its human homolog, MrgX1 [18,50], and can function as a receptor for peptides terminating in RF/Y-G or RF/Y-amide, such as the molluscan peptide FMRFamide, γ2-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH), and bovine adrenal medulla peptide (BAM) [18,33]. Some MrgC ligands belong to the family of endogenous opioid peptides known to be involved in pain transmission. Examples include proenkephalin A gene products BAM8-22 and BAM22 [18,19,33]. Mrgs experienced strong positive selection during evolution and may direct nociception [13,18]. However, reports on the role of MrgC in chronic pain conditions have been disparate and inconsistent [19,21]. Systemic and intrathecal injections of BAM8-22 and γ2-MSH were reported to produce pronociceptive effects in acute pain models and contribute to heat hyperalgesia in an inflammatory pain model [19,23,39]. In contrast, others have shown that intrathecal injection of BAM8-22 inhibits persistent inflammatory pain, chemical pain, and spinal c-fos expression in an opioid-independent manner [6,7,12,26,28,49]. To date, the selectivity and mechanisms of drugs that act on the rodent MrgC receptor have not been clearly demonstrated. Consequently, the therapeutic value of its human homolog MrgX1 as a target for pain treatment is uncertain.

The obstacle to investigating the role of MrgC in pain has been in part a lack of tools for examining its expression (eg, antibody) and function (eg, selective agonist and antagonist). Accordingly, we generated an MrgC-specific antibody for use in immunohistochemical analysis [24] and a dipeptide MrgC-selective agonist (JHU58) for use in functional analysis. We further confirmed that 2,3-disubstituted azabicyclo-octane, previously shown to be an antagonist of human MrgX1 [31], also blocks MrgC activation in vitro. Using these new tools, we tested the hypothesis that MrgC agonism at the spinal level alleviates neuropathic pain manifestations in different rodent models of neuropathic pain, especially that induced by an L5 spinal nerve ligation (SNL). Importantly, we tested the specificity of JHU58 at Mrgs in Mrg-cluster gene knockout mice (Mrg KO) [21,35] and by using MrgC siRNA and the MrgC antagonist in rats. We then examined the effect of Mrg-dependent inhibition of JHU58 on trigeminal neuropathic pain in mice that had undergone chronic constriction injury (CCI) of the infraorbital nerve (ION). Finally, we conducted patch clamp recording in wild-type mice after ION-CCI and SNL to determine if JHU58 attenuates primary excitatory inputs onto postsynaptic dorsal horn neurons.

2. Methods

2.1. Animals and surgery

2.1.1. Mrg KO mice

Chimeric Mrg KO mice were produced by blastocyst injection of positive embryonic stem cells [35]. The KO mice were generated by mating chimeric mice to C57BL/6 mice. The progeny were backcrossed to C57BL/6 mice for at least five generations. Mrg KO mice have a deletion of 845 kb in chromosome 7, which contains 12 intact Mrg genes, including MrgC11 [21,35]. Thus, all nociceptive neuron-expressing Mrgs are deleted in Mrg KO mice [21,35].

2.1.2. Rat L5 SNL

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (200–350 g, Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane. The left L5 spinal nerve was ligated with a 6-0 silk suture and cut distally [30]. The muscle layer was closed with 4-0 chromic gut suture and the skin closed with metal clips.

2.1.3. Mouse SNL

Male C57BL/6 mice (3 weeks old) were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane. The left L5 spinal nerve was exposed and ligated with a 9-0 silk suture and cut distally [40]. The muscle layer was closed with 6-0 chromic gut suture and the skin closed with metal clips.

2.1.4. Mouse sciatic CCI

Adult male C57BL/6 mice (25–35 g) were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane delivered through a nose cone. Under aseptic conditions, the left sciatic nerve at the middle thigh level was separated from the surrounding tissue and loosely tied with three nylon sutures (9-0 nonabsorbable monofilament, S&T AG, Neuhausen, Switzerland) as described previously [21]. The distance between two adjacent ligatures was approximately 0.5 mm.

2.1.5. Mouse ION CCI

The trigeminal nerve is composed of three large branches: the ophthalmic (V1), maxillary (V2), and mandibular (V3). The ION, a major component of the maxillary nerve, was loosely ligated to induce CCI in adult male C57BL/6 mice [47].

2.1.6. Intrathecal catheter implantation

A small slit was cut in the atlanto-occipital membrane of rats, into which a saline-filled piece of PE-10 tubing (6–7 cm) was inserted. After completing the experiment, we confirmed intrathecal drug delivery by injecting lidocaine (400 μg/20 μl, Hospira, Lake Forest, IL), which resulted in a temporary motor paralysis of the lower limbs.

2.2. Animal behavioral tests

All procedures were approved by the Johns Hopkins University and University of Maryland Animal Care and Use Committees as consistent with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Use of Experimental Animals. Animals received food and water ad libidum and were housed on a 12-hour day–night cycle in isolator cages (maximum of 3 rats or 5 mice/cage). All behavioral tests were conducted in the morning. Drugs were tested in nerve-injured rats at the maintenance phase of neuropathic pain (4–5 weeks post-SNL) [20,22]. All behavioral tests and electrophysiology recordings were performed by an experimenter blind to genotype and/or drug treatment conditions.

2.2.1. Paw withdrawal threshold (PWT) test in rats

Hypersensitivity to punctuate mechanical stimulation was determined with the up-down method by using a series of von Frey filaments (0.38–13.1 g) applied for 4–6 seconds to the test area on the plantar surface of the hindpaw [10]. The PWT was determined according to the formula provided by Dixon [17]. Rats that underwent SNL but did not develop mechanical hypersensitivity (>50% reduction of PWT from pre-SNL baseline) by day 5 post-SNL and rats that showed impaired motor function or deteriorating health after treatment were eliminated from the subsequent behavioral studies, and data were not analyzed.

2.2.2. Paw withdrawal frequency (PWF) test in mice

Two calibrated von Frey monofilaments (low force: 0.07 g, high force: 0.45 g) were applied perpendicularly to the plantar side of the hindpaw for approximately 1 second; the same stimulation was repeated 10 times to each hindpaw [21]. The occurrence of paw withdrawal in 10 trials was expressed as a percent response frequency.

2.2.3. Mechanical test of trigeminal neuropathic pain in mice

A series of calibrated von Frey filaments (0.008–4 g) was applied to the orofacial skin within the infraorbital territory. An active withdrawal of the head from the probing filament was defined as a response [47]. Each von Frey filament was applied five times. The response frequencies [(number of responses/number of stimuli) ×100%] to a range of von Frey filament forces were determined. After nonlinear regression analysis, an EF50 value was defined as the von Frey filament force (g) that produced a 50% response frequency.

2.2.4. Pinprick test in rats

Mechanical hyperalgesia was determined by pressing the plantar surface of the hindpaw with a custom-designed pinprick stimulator, which produces a quick reflex withdrawal response in normal animals but is insufficient to damage the skin [14]. Left and right sides were tested three times (5-minute interval). The duration of paw holding/elevation after stimulation was timed in SNL rats with a stopwatch, but it was often too short to be timed accurately in uninjured animals, so a duration of 0.5 seconds was assigned.

2.2.5. Hargreaves test

Paw withdrawal latency (PWL) to radiant heat stimuli (cutoff: 20 seconds) was measured with a plantar stimulator analgesia meter (IITC model 390, Woodland Hills, CA) [14]. Rats were habituated for >30 minutes on a heated glass floor (30°C) before testing. Both hindpaws were tested three times (2-minute interval). The average PWL of the three trials was used for analysis.

2.2.6. Rota-rod test

Motor function of the rats was evaluated with the rota-rod test as described in a previous study [5]. The time that each animal remained on the accelerating rod without falling was recorded.

2.3. Molecular biology

2.3.1. Culture of dissociated DRG neurons and HEK-293 cells

DRGs from 3–4-week-old mice were collected in cold DH10 medium and treated with enzyme solution at 37°C. After trituration and centrifugation, cells were resuspended in DH10, plated on glass coverslips coated with poly-D-lysine and laminin, cultured at 37°C, and used within 24 hours. DRG neurons were electroporated with Mrg expression constructs by using the Mouse Neuron Nucleofector Kit (Amaxa Biosystems, Gaithersburg, MD). HEK-293 cells were cultured in growth medium at 37°C and co-transfected with Mrg expression constructs by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) [35].

2.3.2. Calcium imaging

Neurons were loaded with Fura 2-acetomethoxyl ester (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 30 minutes in the dark at room temperature [24,35]. After being washed, cells were imaged at 340 and 380 nm excitation for detection of intracellular free calcium. Calcium imaging assays were performed by an experimenter blind to genotype.

2.3.3. Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (QRT-PCR)

Reverse transcription PCR was carried out with a modified version of a previously described method [45]. Total RNA was extracted from DRGs by using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). Purified RNA was quantified on the GeneQuant UV spectrophotometer (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) at 260 nm absorbance and assessed for purity by using the 260/280 nm ratio. DNA was reverse transcribed with the Superscript First Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen). PCR amplifications were carried out with a GeneAmp 5700 thermal cycler (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA). The reaction mixture contained 1× SYBR PCR buffer (Perkin-Elmer), 200 μM each of dATP, dCTP, and dGTP, 400 μM dUTP, 0.025 U/μl AmpliTaq Gold, 0.01 U/μl AmpEraseUNG (uracil-N-glycosylase), 3 mM MgCl2, and 200 nM of each primer in a total volume of 50 μl. PCR conditions were 94°C for 3 minutes and 40 cycles of 94°C for 15 seconds, 52°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 45 seconds. The MrgC-specific intron-spanning primers (to avoid genomic contamination) and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) primers were designed by using the Primer Express 1.0 software program (Perkin-Elmer, MrgC-F: CAGCACAAGTCAGCTCCTCAAC; MrgC-R: ATGCCCATGAGAAAGGACAGAACC; GAPDH-F: TGCACCACCAACTGCTTAG; GAPDH-R: GGATGCAGGGATGATGTTC). Melting curve analysis was applied to all final PCR products after the cycling protocol. For each sample, we also carried out PCR reactions with RNA that had not been reverse transcribed to exclude genomic DNA contamination. The PCR products were separated on a 3% (w/v) agarose/Tris-acetate-EDTA gel to confirm the product size. Samples were run in triplicate, and threshold cycle (Ct) values from each reaction were averaged. Tissues from different experimental groups were processed together.

2.3.4. Immunofluorescence

The animals were deeply anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital (100 mg/kg) and perfused intracardially with 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4, 4°C) followed by fixative (4% formaldehyde and 14% [v/v] saturated picric acid in PBS, 4°C). DRG tissues were cryoprotected in 20% sucrose for 24 hours before being serially cut into 25-μm sections and placed onto slides. The slides were pre-incubated in blocking solution (10% normal goat serum, 1 hour) and then incubated overnight at 4°C in primary rabbit polyclonal MrgC antibody (1:500), which was custom-made (Proteintech Group, Inc., Chicago, IL). Slides were incubated in secondary donkey antibody to rabbit (1:100; 711-295-152, Rhod Red-X conjugated, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) for 2 hours at room temperature. The total number of neurons in each section was determined by counting both labeled and unlabeled cell bodies. Tissues from different experimental groups were processed together. Data were analyzed by an investigator blinded to experimental group.

2.4. Whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings from brainstem slices

Tissue from adult C57BL/6 wild-type mice was immersed in ice-cold carbogenated protective artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF). Slices (300 μm) were cut on a tissue slicer (Vibratome VT1200, Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL), transferred to carbogenated protective aCSF at 33°C, and incubated for 1 hour prior to use. Brainstem slices were transferred into a recording chamber and continuously perfused with oxygenated Krebs solution. Superficial neurons of the subnucleus caudalis (Vc) were visualized with infrared Nomarski optics (E600FN, Nikon, Japan). Pipette electrodes (7–10 MΩ) were positioned on the border of the V2 and V3 area of the left substantia gelatinosa of the Vc.

2.5. Whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings from spinal cord slices

A laminectomy was performed in adult C57BL/6 wild-type mice deeply anesthetized with isoflurane (2%, Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL). Then the lumbosacral segment of the spinal cord was rapidly removed and placed in ice-cold, low-sodium Krebs solution (in mM: 95 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 26 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4-H2O, 6 MgCl2, 1.5 CaCl2, 25 glucose, 50 sucrose, 1 kynurenic acid), saturated with 95%O2/5% CO2. The tissue was trimmed and mounted on a tissue slicer (Vibratome VT1200, Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL). Transverse slices (400 μm) with attached dorsal roots were prepared and then incubated in preoxygenated low-sodium Krebs solution without kynurenic acid. The slices recovered at 34°C for 40 minutes and then at room temperature for an additional 1 hour before experimental recordings. Whole-cell patch-clamp recording of lamina II cells was carried out under oblique illumination with an Olympus fixed-stage microscope system (Melville, NY). Slices were transferred into a low-volume recording chamber and continuously perfused with room-temperature Krebs solution (in mM: 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 26 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4-H2O, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 25 glucose) bubbled with a continuous flow of 95% O2/5% CO2 at a rate of 5 ml/min. Data were acquired with pClamp 10 software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) and a Multiclamp amplifier. Thin-walled glass pipettes (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) were fabricated with a puller (P1000, Sutter, Novato, CA) with resistances of 3–6 MΩ and filled with internal saline (in mM: K-gluconate 120, KCl 20, MgCl2 2, EGTA 0.5, Na2-ATP 2, Na2-GTP 0.5, and HEPES 20). The cells were voltage clamped at −70 mV. Membrane current signals were sampled at 10 kHz and low-pass filtered at 2 kHz.

2.6. Drugs

Stock solutions were freshly prepared as instructed by the manufacturer. BAM8-22, FMRFamide, and JHU58 were all diluted in saline or extracellular solution. JHU58 and 2,3-disubstituted azabicyclo-octane were synthesized by Johns Hopkins University. Other drugs were purchase from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) or Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, UK).

2.7. Statistical analysis

The methods for statistical comparisons in each study are given in the figure legends. The number of animals used in each study was based on our experience with similar studies and power analysis calculations. We randomized animals to the different treatment groups and blinded the experimenter to drug treatment to reduce selection and observation bias. After the experiments were completed, no data point was excluded. Representative data are from experiments that were replicated biologically at least three times with similar results. STATISTICA 6.0 software (StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, OK) was used to conduct all statistical analyses. The Tukey honestly significant difference (HSD) post-hoc test was used to compare specific data points. Bonferroni correction was applied for multiple comparisons. Two-tailed tests were performed, and data are expressed as mean ± SEM; P<0.05 was considered significant in all tests.

3. Results

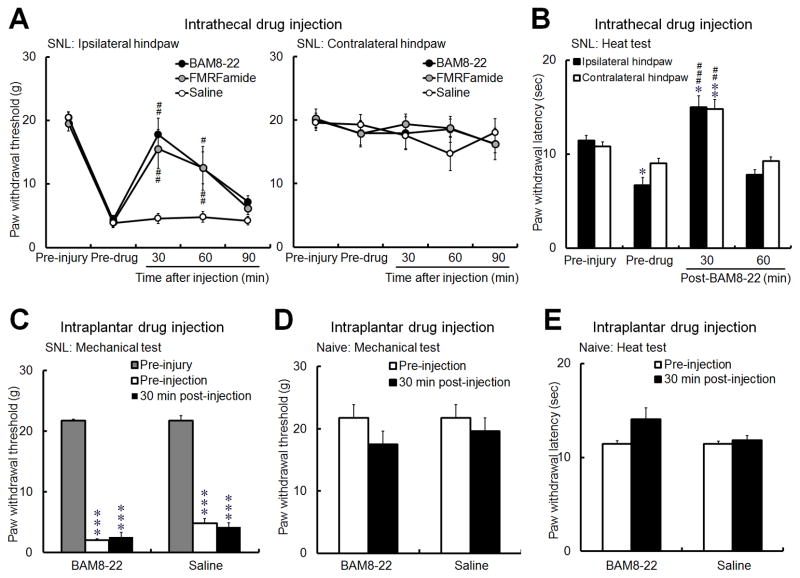

3.1. Intrathecal, but not peripheral, administration of a peptide MrgC agonist alleviates neuropathic pain in rats

We first determined the site(s) at which BAM8-22, a 15-amino acid peptide MrgC agonist that has been tested in previous studies [21,25], can inhibit neuropathic pain in SNL rats. Intrathecal injection of BAM8-22 (0.5 mM, 10 μl, n=8) and a less-selective MrgC agonist (molluscan peptide FMRFamide, 2 mM, 10 μl, n=7), but not saline (n=6), inhibited mechanical hypersensitivity in the ipsilateral hindpaw of SNL rats, as indicated by a significant increase in PWTs at 30 and 60 minutes after injection (Fig. 1A). Intrathecal BAM8-22 (0.5 mM, 10 μl, n=5) also reversed heat hypersensitivity of the ipsilateral hindpaw in SNL rats, as indicated by a significant increase in PWL at 30 minutes after injection (Fig. 1B). However, neither BAM8-22 (1 mM, 30 μl, n=8) nor saline (30 μl, n=6) significantly changed PWT in SNL rats when administered by intraplantar injection into the ipsilateral hindpaw (Fig. 1C). In naïve rats, intraplantar injection of neither BAM8-22 at a higher dose (3 mM, 30 μl, n=6) nor saline (30 μl, n=6) altered mechanical PWT or PWL to noxious heat stimuli (Fig. 1D). These data suggest that the pain-inhibitory effects of BAM8-22 rely on a spinal site of action, presumably through activation of MrgC receptors on the central terminals of DRG neurons. Accordingly, subsequent behavioral studies of MrgC ligand were carried out solely through intrathecal drug administration.

Fig. 1. Administration of BAM8-22 in the spinal cord, but not in peripheral tissue, inhibits neuropathic pain in rats.

(A) BAM8-22 (0.5 mM, 10 μl, n=8) and molluscan peptide FMRFamide (2 mM, 10 μl, n=7) significantly increased paw withdrawal threshold (PWT) in the ipsilateral hindpaw of rats with spinal nerve ligation (SNL) at 30 and 60 minutes after intrathecal injection; saline injection (n=6) had no effect. (B) Intrathecal BAM8-22 (0.5 mM, 10 μl, n=5) also increased paw withdrawal latency (PWL) to noxious heat stimuli in both ipsilateral and contralateral hindpaws in SNL rats. (C) However, intraplantar injection of BAM8-22 (1 mM, 30 μl, n=8) or saline (30 μl, n=6) into the ipsilateral hindpaw of SNL rats did not significantly change PWT from the pre-injection level. (D, E) In naïve rats, intraplantar injection of neither a higher dose of BAM8-22 (3 mM, 30 μl, n=6) nor saline (30 μl, n=6) altered mechanical PWT (D) or PWL (E) to noxious heat stimuli. The drug effects were examined 30 minutes after injection in C–E. #P<0.05, ##P<0.01, ###P<0.001 versus pre-injection; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 versus pre-injury. One-way repeated measures ANOVA (A-C); paired t-test (D, E).

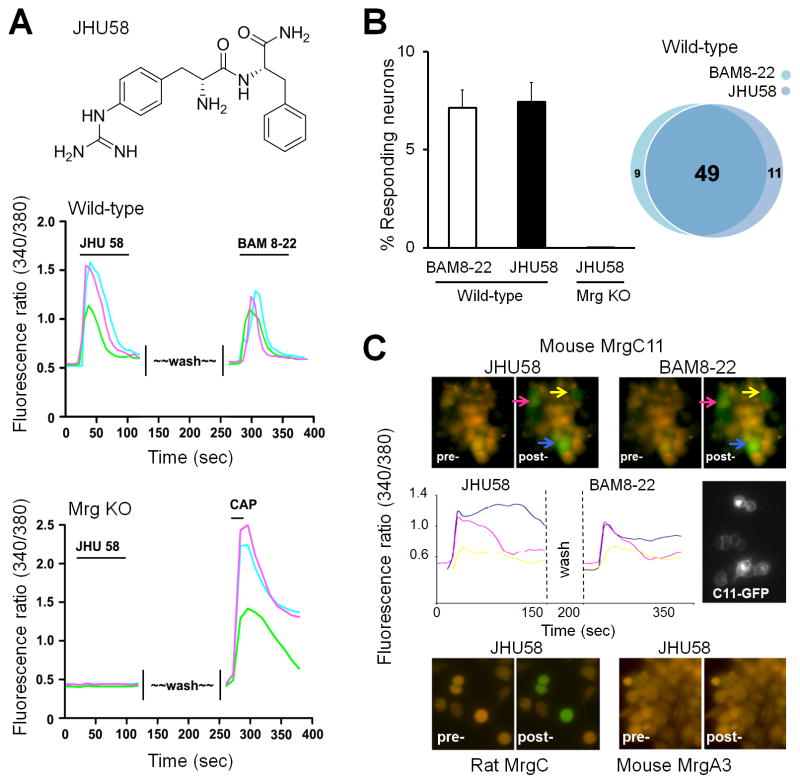

3.2. JHU58 is a novel MrgC agonist

Because BAM8-22 is a 15-amino acid peptide, its stability and tissue penetration were a concern. Our efforts to design and synthesize multiple truncated analogs of BAM8-22 led to discovery of the MrgC-selective agonist JHU58, a peptidomimetic of Arg-Phe-NH2 (Fig. 2A; synthesis and chemical characterization are described in a separate publication). In cultured DRG neurons (n=827) from wild-type mice, bath application of JHU58 (3 μM) induced a transient increase in [Ca2+]i similar to that produced by BAM8-22 (2 μM, Fig. 2A). Further, JHU58-responsive cells (n=60) largely overlapped with BAM8-22–responsive cells (n=58) in wild-type DRG neurons (Fig. 2B). Importantly, JHU58 (3 μM) did not induce an increase in [Ca2+]i in any of the DRG neurons (n=463) from Mrg KO mice (Fig. 2A,B). Subsequent bath application of capsaicin (0.5 μM, positive control) evoked an increase in [Ca2+]i in 32% of DRG neurons from Mrg KO mice, indicating that the lack of response to JHU58 was not due to poor cell condition. Finally, JHU58 (3 μM) selectively induced a transient increase in [Ca2+]i in HEK-293 cells transfected with mouse MrgC11 or rat rMrgC (Fig. 2C). However, cells transfected with other Mrg subtypes (eg, MrgA3) did not respond to JHU58. Together, these findings suggest that JHU58 is an MrgC-selective agonist. Using a high-throughput screening assay based on a calcium imaging technique, we found that the EC50 values for JHU58 and BAM8-22 to induce a calcium transient were 0.6 μM and 0.3 μM, respectively, in HEK-293 cells expressing rat MrgC, and 1.0 μM and 0.3 μM, respectively, in HEK-293 cells expressing mouse MrgC11.

Fig. 2. JHU58 is a novel MrgC agonist.

(A) Upper panel: The structure of JHU58, a peptidomimetic of Arg-Phe-NH2. Middle panel: Representative calcium-imaging traces (marked with different colors) in cultured DRG neurons from wild-type mice show that [Ca2+]i increases after bath application of JHU58 (3 μM) and after the subsequent application of BAM8-22 (2 μM). Lower panel: Representative calcium-imaging traces in DRG neurons from Mrg-cluster gene knockout mice (Mrg KO) show that [Ca2+]i increases after bath application of capsaicin (CAP; 0.5 μM) but not JHU58 (3 μM). (B) BAM8-22 and JHU58 activated a similar proportion (bar graph) and overlapping population (Venn diagram) of DRG neurons (n=827) from wild-type mice. However, JHU58 did not induce an increase in [Ca2+]i in any of the DRG neurons (n=463) from Mrg KO mice (bar graph). (C) Upper panel: JHU58 (3 μM) induced a transient increase (green) in [Ca2+]i in HEK-293 cells (marked with colored arrows) transfected with MrgC11 that are also activated by BAM8-22 (2 μM). Middle panel: Representative traces from three HEK-293 cells show an increase in [Ca2+]i after bath application of JHU58 and BAM8-22. The MrgC11-transfected cell can be seen by the co-expression of green fluorescent protein. Lower panel: JHU58 also induced a transient calcium influx (green) in cells transfected with rat MrgC, but not in cells transfected with mouse MrgA3.

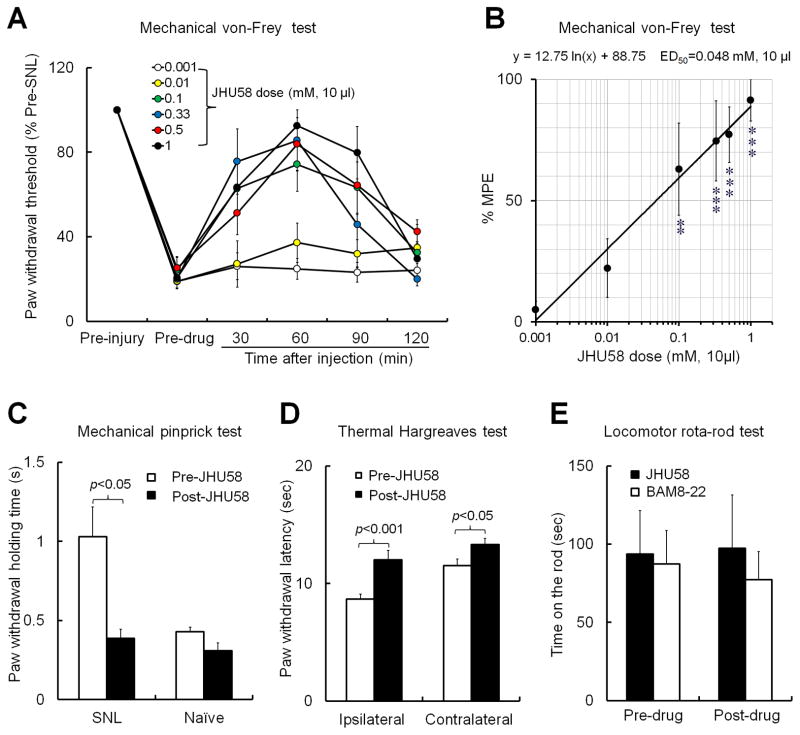

3.3. Intrathecal JHU58 inhibits various manifestations of neuropathic pain

We next tested whether MrgC agonism with JHU58 at the spinal level inhibits chronic neuropathic pain. Mechanical allodynia is a common manifestation of neuropathic pain. We found that intrathecal JHU58 (0.001–1 mM, 10 μl, n=5–9/dose) dose dependently inhibited behavioral hypersensitivity to non-noxious tactile stimulation in rats after an L5 SNL (Fig. 3A,B). The dose-response function was established based on the % Maximum Possible Effect (%MPE) at 60 minutes post-injection (peak effect). %MPE = [(post-drug PWT) – (pre-drug PWT)]/[(cutoff) – (pre-drug PWT)] × 100. %MPE values were plotted against the doses of JHU58 on a logarithmic scale, and ED50 (dose estimated to produce 50% MPE) for reversing mechanical allodynia was calculated accordingly. Intrathecal JHU58 (0.1 mM, 10 μl) also attenuated mechanical hyperalgesia to noxious pinprick stimuli in the ipsilateral hindpaw of SNL rats (n=4), but it had no effect in naïve rats (n=7, Fig. 3C). Intrathecal JHU58 (0.1 mM, 10 μl, n=12) not only alleviated heat hypersensitivity in the ipsilateral hindpaw of SNL rats, but also induced heat antinociception in the contralateral hindpaw (Fig. 3D), as indicated by PWLs that were increased from the pre-injection levels. In the rota-rod test, therapeutic doses of neither JHU58 (0.1 mM, 10 μl, n=5) nor BAM8-22 (1.0 mM, 10 μl, n=6) impaired locomotor function in SNL rats, which were examined at 30–60 min post-injection (Fig. 3E). Finally, intrathecal infusion of neither BAM8-22 nor JHU58 at the doses tested elicited signs of discomfort (eg, scratching, vocalizing, escaping, sudden and rigorous adjusting of body posture) in rats. Mice exhibited brief and mild irritation (tail flick, 3–5 times/minute) that lasted 1–2 minutes after lumbar puncture injection of JHU58. However, this irritation occurred in both wild-type and Mrg KO mice, suggesting that it was a nonselective action associated with the injection procedure and mediated through an Mrg-independent mechanism or by Mrg family members that were not part of the deleted cluster.

Fig. 3. Intrathecal JHU58 inhibits neuropathic pain manifestations in rats.

(A) In rats with spinal nerve ligation (SNL), intrathecal JHU58 (0.001–1 mM, 10 μl, n=5-9/dose) dose dependently increased ipsilateral paw withdrawal thresholds, reflecting attenuated mechanical hypersensitivity. (B) The dose-response function was established based on the % Maximum Possible Effect (%MPE) at 60 minutes post-injection (peak effect). **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 versus 0.001 mM group, one-way ANOVA. (C) Intrathecal JHU58 (0.1 mM, 10 μl) also attenuated mechanical hyperalgesia to pinprick stimuli in the ipsilateral hindpaw of SNL rats (n=4) but had no effect in naïve rats (n=7). (D) Intrathecal JHU58 (0.1 mM, 10 μl, n=12) increased paw withdrawal latency to noxious heat stimuli in both hindpaws of SNL rats. (E) Intrathecal JHU58 (0.1 mM, 10 μl, n=5) and BAM8-22 (1.0 mM,10 μl, n=6, delivered 30 minutes before rota-rod test) did not induce motor dysfunction in SNL rats. Paired t-test (C–E).

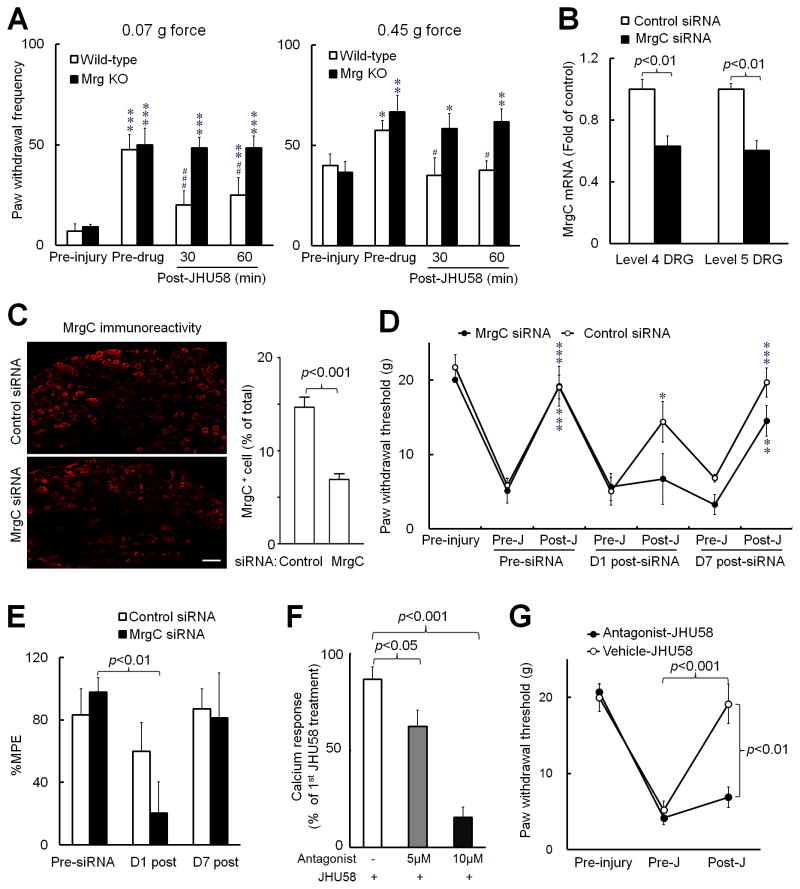

3.4. JHU58-induced analgesia is MrgC-dependent

Next we examined whether JHU58-induced pain inhibition in vivo depends on MrgC receptor activation. First we found that intrathecal JHU58 (0.5 mM, 5 μl) attenuated neuropathic mechanical allodynia in wild-type mice (n=5), but not in Mrg KO mice (n=6, Fig. 4A), suggesting that the mechanism is Mrg-dependent. Then we knocked down rMrgC expression in rats with four once-daily intrathecal injections of rMrgC siRNA. The rMrgC mRNA levels in lumbar DRGs were significantly lower in naïve rats that received rMrgC siRNA (5 μg/25 μl/day, n=6) than in those that received mismatch siRNA (control, n=4, Fig. 4B). Likewise, the percentage of MrgC+ neurons was significantly decreased in lumbar DRGs of naïve rats at 1 day after the fourth rMrgC siRNA injection (n=4), as compared to that in rats that received mismatch siRNA (n=5, Fig. 4C). As in the Mrg KO mice, downregulation of rMrgC expression with siRNA abolished JHU58-induced analgesia in SNL rats at 1 day after the fourth rMrgC siRNA injection (Fig. 4D). In contrast, mismatch siRNA injections had no effect on JHU58-induced increases in ipsilateral PWT of SNL rats (Fig. 4D). In an in vitro calcium imaging study, pretreatment with 2,3-disubstituted azabicyclo-octane (3 minutes, 5 μM: n=9, 10 μM: n=26), which has been suggested to be a competitive antagonist for MrgX1 (human homolog of MrgC) [31], dose dependently blocked JHU58 (5 μM)-induced calcium transients in rat DRG neurons (Fig. 4F) and inhibited BAM8-22 activation of HEK-293 cells transfected with MrgC11 (data not shown). Thus, 2,3-disubstituted azabicyclo-octane is also an MrgC antagonist. Finally, pretreatment with intrathecal 2,3-disubstituted azabicyclo-octane (0.2 mM, 10 μl, n=8), but not vehicle (n=6), blocked JHU58-induced pain inhibition in SNL rats (Fig. 4G). Together, these data demonstrate that selective, in vivo activation of MrgC by JHU58 results in pain relief.

Fig. 4. JHU58-induced pain inhibition depends on MrgC receptor activation in vivo.

(A) Intrathecal JHU58 (0.5 mM, 5 μl) significantly reduced the increased ipsilateral paw withdrawal frequencies to low force (0.07 g) and high force (0.45 g) punctuate mechanical stimuli in wild-type mice (n=5), but not in Mrg-cluster gene knockout mice (Mrg KO, n=6), after sciatic chronic constriction injury. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 versus pre-injury; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01, ###P<0.001 versus pre-drug. (B) The MrgC mRNA levels in lumbar DRGs were significantly lower in naïve rats that received four once-daily intrathecal infusions of MrgC siRNA (5 μg/25 μl/day, n=6) than in those that received mismatch siRNA (control, n=4). (C) The percentage of MrgC+ neurons was also significantly reduced in lumbar DRGs of naïve rats 1 day after the fourth MrgC siRNA treatment (n=4), as compared to that of rats that received control siRNA (n=5). Scale bar: 50 μm. (D) On day 1 (D1) post-siRNA treatment, JHU58 (J, 0.1 mM, 10 μl) significantly increased the ipsilateral paw withdrawal threshold in rats with spinal nerve ligation (SNL) that were pretreated with control siRNA (n=5), but not in those pretreated with MrgC siRNA (5 μg/25 μl/day on days 9 to 13 post-SNL, n=5). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 versus pre-JHU58. (E) The % Maximum Possible Effect (%MPE) of JHU58 to inhibit mechanical allodynia was significantly decreased from the pre-siRNA value in the MrgC siRNA-treated group. (F) JHU58 (5 μM) evoked calcium transients in rat DRG neurons. The second JHU58 (5 μM) treatment minimally reduced the [Ca2+]i increase (white bar, n=7). However, the calcium transient was significantly reduced by a 3-minute pretreatment with MrgC antagonist 2,3-disubstituted azabicyclo-octane (5 μM: n=9, 10 μM: n=26). (G) In SNL rats, pretreatment with intrathecal 2,3-disubstituted azabicyclo-octane (0.2 mM, 10 μl, n=8), but not vehicle (n=6), blocked inhibition of mechanical hypersensitivity by JHU58 (0.3 mM,10 μl). Unpaired t-test (B,C,F); one-way repeated measures ANOVA (A,D,E); two-way mixed model ANOVA (G).

3.5. JHU58 alleviates mechanical hypersensitivity and decreases the enhanced primary excitatory inputs onto medullary dorsal horn neurons after trigeminal nerve injury

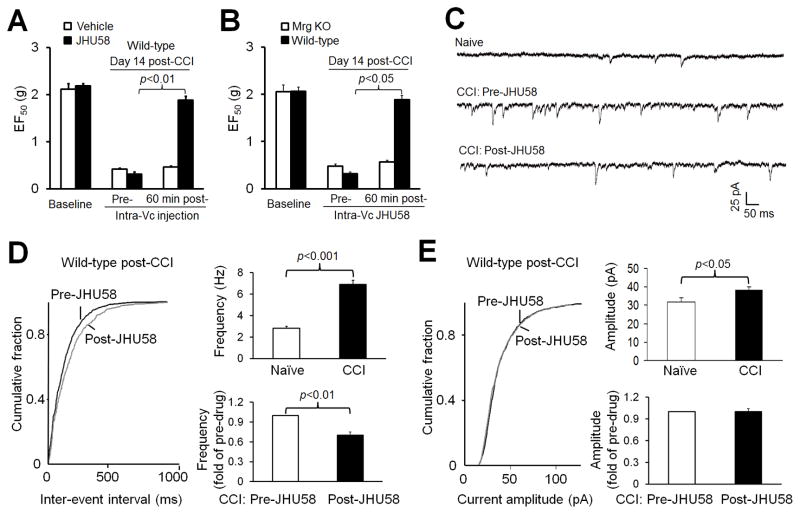

The orofacial region is a focus of persistent pain after trigeminal nerve injury, and pain processing may differ between the trigeminal system and spinal system. To generalize JHU58-induced analgesia from rat SNL and mouse sciatic CCI models of neuropathic pain, we asked whether intramedullary injection of JHU58 also induces an Mrg-dependent inhibition of neuropathic pain that results from injuries to the trigeminal system. The EF50 threshold, the von Frey filament force that produces a 50% response frequency, was decreased in mice on day 14 after ION-CCI. Microinjection of JHU58 (0.2 mM, 0.5 μl, n=6, paired t-test), but not vehicle (n=6), into the ipsilateral Vc, the trigeminal homolog of the spinal cord, significantly increased EF50 after 60 minutes (Fig. 5A). This finding suggests that JHU58 attenuated mechanical hypersensitivity in skin of the infraorbital territory, consistent with our observation in the rat SNL and mouse sciatic CCI models. In a separate study, microinjection of JHU58 (0.2 mM, 0.5 μl) into the ipsilateral Vc significantly increased EF50 threshold from pre-drug level in wild-type littermates (n=6) but not in Mrg KO mice (n=6, paired t-test) on day 14 after ION-CCI (Fig. 5B). Thus, JHU58 also inhibits neuropathic pain that results from injuries to the trigeminal system, and the effect is Mrg-dependent.

Fig. 5. JHU58 inhibits mechanical hypersensitivity and decreases miniature excitatory postsynaptic current (mEPSC) frequency in medullary dorsal horn neurons of wild-type mice after trigeminal nerve injury.

(A) The threshold for the von Frey filament force that produced a 50% response frequency (EF50) was decreased in mice on day 14 after chronic constriction injury (CCI) of the infraorbital nerve (ION). Microinjection of JHU58 (0.2 mM, 0.5 μl, n=6, paired t-test), but not vehicle (n=6), into the ipsilateral subnucleus caudalis significantly increased EF50 after 60 minutes. (B) In a separate study, JHU58 (0.2 mM, 0.5 μl) significantly increased EF50 threshold in wild-type littermates (n=6) but not in Mrg-cluster gene knockout mice (Mrg KO, n=6, paired t-test) on day 14 post-CCI, as compared to pre-drug level. (C) Examples of mEPSC recorded in medullary dorsal horn neurons of naïve mice and in ION-CCI mice before and after bath application of JHU58 (5 μM). (D) Left: An example of the cumulative probability distribution of inter-event intervals for mEPSCs shifted rightward in ION-CCI mice after JHU58 treatment, indicating decreased frequency. Right: The mEPSC frequency in subnucleus caudalis neurons from ION-CCI mice (n=8) was significantly higher than that in neurons from naïve animals (n=7, Student t-test). JHU58 (5 μM) significantly decreased the frequency of mEPSC events in ION-CCI mice (0.7 ± 0.05 fold of pre-drug, n=8, paired t-test). (E) Left: The amplitude of mEPSC was significantly increased after CCI (Student t-test). However, the amplitude of mEPSC in ION-CCI mice was not affected by JHU58 treatment (5 μM; 1.0 ± 0.04 fold of pre-drug, paired t-test).

We then examined whether JHU58 alleviates trigeminal neuropathic pain through an inhibition of excitatory presynaptic responses in the Vc. We conducted patch-clamp recording of substantia gelatinosa neurons (lamina II) that exhibited miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) in Vc slices from ION-CCI mice. The mEPSC frequency in the ipsilateral Vc neurons from mice at day 14 after ION-CCI (n=8) was significantly higher than that in neurons from naïve animals (n=7, Fig. 5C,D), indicating an enhanced ectopic peripheral input after nerve injury. Bath application of JHU58 (5 μM) significantly attenuated the increased frequency of mEPSCs induced by ION-CCI (0.7 ± 0.05 fold of pre-drug, n=8, Fig. 5C, D) but did not affect mEPSC amplitude (1.0 ± 0.04 fold of pre-drug, Fig. 5E). These findings suggest that JHU58 may inhibit the enhanced primary excitatory inputs onto postsynaptic Vc neurons after ION-CCI.

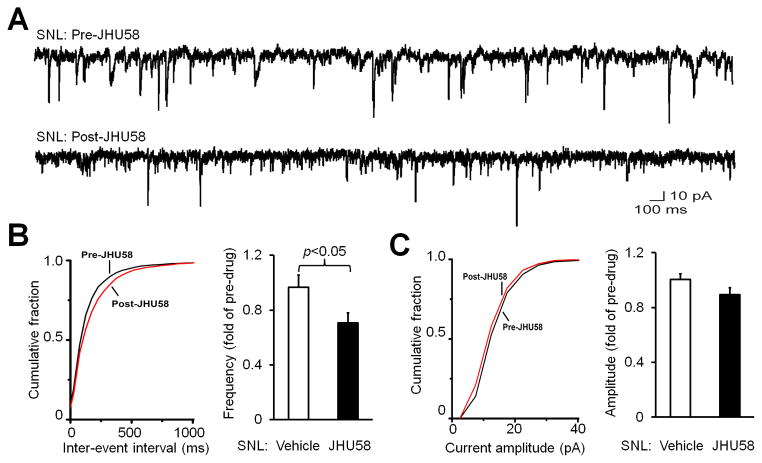

3.6. JHU58 decreases mEPSC frequency in spinal dorsal horn neurons after spinal nerve injury

Finally, we examined whether JHU58 also inhibits mEPSC in substantia gelatinosa neurons in the lumbar spinal cord (L4-L5 spinal segment) of adult wild-type mice after SNL. The mEPSC frequency in the ipsilateral substantia gelatinosa neurons of mice 7–14 days post-SNL (n=8) was significantly reduced (0.71 ± 0.07 fold of pre-drug) after bath application of JHU58 (5 μM), as compared to that after vehicle treatment (0.97 ± 0.09 fold of pre-drug, Fig 6A,B). Accordingly, the cumulative probability distribution of inter-event intervals for mEPSCs shifted rightward after JHU58 treatment. However, the amplitude of mEPSC in these neurons was not significantly decreased by JHU58 (Fig 6C), as compared to vehicle treatment.

Fig. 6. JHU58 decreases miniature excitatory postsynaptic current (mEPSC) frequency in the superficial dorsal horn neurons of wild-type mice after spinal nerve injury.

(A) Examples of mEPSC before and after bath application of JHU58 (5 μM). mEPSC was recorded in substantia gelatinosa (lamina II) neurons from lumbar spinal cord slices of wild-type mice that underwent spinal nerve ligation (SNL). (B) Left: An example of the cumulative probability distribution of inter-event intervals for mEPSCs, which shifted rightward afterJHU58 treatment in SNL mice, indicating decreased frequency. Right: At 7–14 days after SNL, the mEPSC frequency in dorsal horn neurons was significantly less in JHU58-treated mice (5 μM; n=8) than in vehicle-treated mice (n=8, Student t-test). (C) Left: An example of the cumulative probability distribution of the amplitude of mEPSC before and after JHU58 treatment. Right: JHU58 did not significantly change the amplitude of mEPSC compared to that after vehicle treatment.

4. Discussion

The MrgC receptor may be transported from cell body to both peripheral and central terminals, as indicated by a specific radioligand binding assay and an immunohistochemical study [19,23,24]. Using BAM8-22, we first determined that MrgC agonism inhibits neuropathic pain manifestations in rats by acting at a spinal site, presumably at the central terminals of afferent neurons in the dorsal horn, but not at peripheral nerve endings in the skin. This finding supports the premise that MrgC ligands function as antihyperalgesic agents at the spinal level [6,21]. In our study, an intraplantar injection of BAM8-22 did not attenuate mechanical allodynia in nerve-injured rats, nor did it significantly change mechanical and heat hypersensitivity in naïve rats. Yet, it remains possible that the MrgC agonist may act at other peripheral sites (eg, along the course of the nerve) to modulate pain. Information regarding the roles of MrgC in persistent pain states is sparse and conflicting [12,19,25,28]. After verifying that intrathecal BAM8-22 induces analgesia under neuropathic pain conditions, we demonstrated that JHU58, a novel MrgC agonist, provides broad inhibition of different neuropathic pain manifestations. Specifically, JHU58 alleviated both mechanical allodynia (von Frey test) and mechanical hyperalgesia (pinprick test) in SNL rats. The inhibition of mechanical allodynia by JHU58 was dose-dependent and lasted for more than 1 hour. Both JHU58 and BAM8-22 also reversed heat hyperalgesia in SNL rats and produced thermal antinociception, as indicated by the increase in ipsilateral PWL above pre-injury baseline and by the increase in contralateral PWL after drug treatment. To preserve the protective thermal nociception, dose titration may be needed for an MrgC agonist to achieve a selective antihyperalgesic effect.

Interpreting the effect of “selective Mrg compounds” on pain in vivo has been difficult because of the apparent promiscuity of Mrg for a number of ligands. For example, γ2-MSH, another putative MrgC ligand, is also the endogenous ligand for the MC3 melanocortin receptor. Thus, one limitation in previous peptide injection experiments is that the selectivity and receptor mechanism of drug action were not directly addressed. Our in vitro studies suggested that MrgC is the rodent receptor for BAM8-22 and JHU58; both compounds activated HEK-293 cells transfected with rat MrgC and mouse MrgC11, but not cells transfected with other rodent Mrg subtypes. The similarity in drug actions and overlap between JHU58- and BAM8-22–responding DRG cells suggest that they may target the same receptor. In our previous study, BAM8-22–induced drug action was completely lost in Mrg-deficient DRG neurons, in wild-type DRG neurons electroporated with MrgC11 siRNA, and in neurons treated with MrgC antagonist 2,3-disubstituted azabicyclo-octane [35]. In the current study, JHU58-induced drug action was also completely lost in Mrg mutant DRG neurons. Although our in vitro study suggested that MrgC is the major receptor for BAM8-22 and JHU58, it is still critical to determine the specificity of these compounds for pain inhibition in vivo. We have shown previously that deletion of the Mrg gene cluster eliminates the analgesic effect of intrathecally applied BAM8-22 on neuropathic mechanical allodynia [21]. Furthermore, BAM8-22 attenuated windup of the wide-dynamic-range neuronal response to repetitive noxious inputs in wild-type mice, an effect also eliminated in Mrg KO mice [21]. Because MrgC11 is the only Mrg absent from the Mrg KO mouse that is activated by BAM8-22, these findings suggest that the pain inhibitory effect of BAM8-22 is most likely mediated by MrgC11 signaling in mice. Here, we found that deletion of the Mrg gene cluster, MrgC siRNA, and an MrgC-selective antagonist each eliminated or significantly reduced JHU58-induced analgesia. Thus, MrgC is also likely the receptor responsible for intrathecal JHU58-induced analgesia in vivo.

Suppression of gene expression in DRG neurons can be achieved by intrathecal delivery of siRNA [27,34,37,39]. In our study, the MrgC mRNA levels in lumbar DRGs were significantly reduced by intrathecal MrgC siRNA treatment. The decrease in mRNA was accompanied by a decrease in percentage of MrgC+ neurons in lumbar DRGs, confirming the efficacy of in vivo gene silencing by MrgC siRNA. Although we have not found MrgC mRNA in spinal cord [18,35], it is possible that MrgC siRNA may have nonselective actions on dorsal horn neurons. To confirm MrgC siRNA specificity, changes in the expression of other genes in DRG and spinal cord after siRNA treatment need to be examined. Nevertheless, mismatch siRNA treatment did not significantly decrease MrgC expression or JHU58-induced pain inhibition, suggesting that the siRNA we used is selective for MrgC. Previously, we demonstrated the specificity of MrgC antibody in Mrg KO mice [24]. Although we cannot rule out the possibility that the antibody could react with other members of the Mrg family, as several other Mrg subtypes are deleted in the Mrg KO mice, the likelihood of this cross-reactivity is low because the peptide antigen used to generate the antibody is present only in MrgC.

Our study supports previous observations that intrathecal injection of BAM8-22 inhibits persistent inflammatory pain, chemical pain, and spinal c-fos expression in an opioid-independent manner [6,7,26,28,49]. However, it contradicts other reports that BAM8-22 has a pronociceptive effect [19,39]. The reasons for these contradictory findings remain unclear, but may relate to differences in animal conditions and etiologies (physiologic condition versus nerve injury) [4,29,41], behavioral measures (spontaneous versus reflex), and drug dose. The pronociceptive effect (eg, scratching) after injection of BAM8-22 into skin can also be due to itch [44], as MrgC may function in sensory processing of itch at peripheral terminals in skin [35,44,48]. However, intrathecal injection of MrgC agonists at the doses we tested inhibited neuropathic pain manifestations without eliciting itch-like behavior or signs of discomfort. Further, intraplantar injection of MrgC agonists produced no pain inhibition. It is unclear why peripheral injections of MrgC agonists induce itch whereas central administration inhibits pain, but the difference may relate in part to drug dose or local concentration. Inducing an itch response usually requires high local drug concentrations (eg, BAM8-22 > 1 mM) after intracutaneous injections into hairy skin, but intrathecal MrgC agonists induce analgesia at lower doses (eg, BAM8-22: 0.5 mM, JHU58: 0.05 mM, 10 μl). Other G-protein-coupled receptor ligands (eg, serotonin, capsaicin) also have different effects on pain and other sensations when applied at different locations. For example, capsaicin induces burning pain in the periphery, but it inhibits pain when applied centrally [9,32]. This central inhibition by capsaicin may involve presynaptic inhibition [38]. Finally, the varied effects of MrgC agonists may also be caused by differential distribution and compartmentalization of MrgC and by coupling of different downstream targets (eg, Gi and Gq) at peripheral (e.g., TRP channels) and central (e.g., calcium channels) terminals [16,36,48].

The precise mechanisms that underlie the analgesic effects of MrgC agonism remain unclear and are probably multiple. MrgC may couple to both Gi and Gq pathways and thus cause different cellular effects [25]. Intriguingly, BAM8-22 inhibits high-voltage-activated (HVA) Ca2+ channels in cells that express human MrgX1 [11]. The inhibition of HVA Ca2+ channels by BAM8-22 is pertussis toxin-sensitive, indicating involvement of the Gi pathway [11]. Activation of HVA Ca2+ channels plays an important role in neurotransmitter release and in transmission of nociceptive stimuli in DRG neurons [2,8]. If activation of MrgC also inhibits HVA Ca2+ currents in native rodent DRG neurons, MrgC agonists might reduce presynaptic neurotransmitter release into dorsal horn, thereby inhibiting pain. In line with this possibility, JHU58 attenuated the mEPSC frequency in substantia gelatinosa neurons in both medullary dorsal horn of ION-CCI mice and lumbar spinal dorsal horn of SNL mice. These novel findings suggest that inhibition of the peripheral excitatory inputs onto postsynaptic dorsal horn neurons may be a common cellular mechanism by which intrathecal JHU58 induces pain inhibition after nerve injury. Intrathecal BAM8-22 dose-dependently diminished NMDA-evoked pain behaviors in rats, suggesting that it may induce spinal analgesia by suppressing NMDA receptor-mediated excitation on dorsal horn neurons [12]. A recent study reported that activation of MrgC also suppresses upregulation of pronociceptive mediators (eg, nNOS, CGRP) and c-fos expression in the dorsal horn under inflammatory pain conditions [28], increases mRNAs that code for μ-opioid receptors and proopiomelanocortin in the lumbar spinal cord, and modulates the coupling of μ-opioid receptors with Gi-protein [46]. Therefore, an MrgC agonist might inhibit pain through both direct and indirect mechanisms [28]. So far, the effects of MrgC activation on afferent sensory neuronal responsiveness and spinal pain transmission remain largely elusive. Thus, the underlying cellular and neurobiologic mechanisms of MrgC-mediated pain inhibition are still an open question.

Knowledge of pain-inhibitory systems, such as opioidergic and adrenergic systems, has led to significant improvement in pain treatment [1,15,41]. Here, we provide multiple lines of evidence that MrgC agonism at spinal sites may constitute a novel pain inhibitory mechanism for neuropathic pain in rodents. Because MrgC shares substantial homogeneity with its human homolog, MrgX1 [18,33], our findings may provide proof of principle for developing MrgX1 agonists for the treatment of neuropathic pain in humans.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources: This study was supported by grants from the NIH: NS70814 (Y.G.), NS58481 (X.D.), GM087369 (X.D.), NS26363 (S.N.R.), DE18573 (F.W.); the Johns Hopkins Blaustein Pain Research Fund (Y.G.); and Brain Science Institute Awards (Y.G., X.D.). X.D. is an Early Career Scientist of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

The authors thank Claire F. Levine, MS (scientific editor, Department of Anesthesiology/CCM, Johns Hopkins University), for editing the manuscript and Yixun Geng and Alene Carteret for mouse genotyping and maintenance.

Footnotes

Author contributions

S-Q.H and Z.L. performed most of the experiments and were involved in writing a draft manuscript. Y-X.C., Q.X., M.L., Y.F., H.L., Q.L., R.S., Y.W., Z.T., and V.T. also conducted some of the electrophysiology, molecular, and behavioral experiments. T.T., N.H., and B.S. developed and synthesized the JHU compounds. F.W. and S.N.R. were involved in experimental design and data analysis. Y.G. and X.D. designed and directed the project and wrote the final manuscript. None of the authors has a commercial interest in the material presented in this paper.

There are no other relationships that might lead to a conflict of interest in the current study.

Disclosures: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Agarwal N, Pacher P, Tegeder I, Amaya F, Constantin CE, Brenner GJ, Rubino T, Michalski CW, Marsicano G, Monory K, Mackie K, Marian C, Batkai S, Parolaro D, Fischer MJ, Reeh P, Kunos G, Kress M, Lutz B, Woolf CJ, Kuner R. Cannabinoids mediate analgesia largely via peripheral type 1 cannabinoid receptors in nociceptors. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:870–9. doi: 10.1038/nn1916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altier C, Zamponi GW. Targeting Ca2+ channels to treat pain: T-type versus N-type. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:465–70. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baron R. Mechanisms of disease: neuropathic pain--a clinical perspective. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2006;2:95–106. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Basbaum AI. Distinct neurochemical features of acute and persistent pain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:7739–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.7739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brittain JM, Duarte DB, Wilson SM, Zhu W, Ballard C, Johnson PL, Liu N, Xiong W, Ripsch MS, Wang Y, Fehrenbacher JC, Fitz SD, Khanna M, Park CK, Schmutzler BS, Cheon BM, Due MR, Brustovetsky T, Ashpole NM, Hudmon A, Meroueh SO, Hingtgen CM, Brustovetsky N, Ji RR, Hurley JH, Jin X, Shekhar A, Xu XM, Oxford GS, Vasko MR, White FA, Khanna R. Suppression of inflammatory and neuropathic pain by uncoupling CRMP-2 from the presynaptic Ca(2)(+) channel complex. Nat Med. 2011;17:822–9. doi: 10.1038/nm.2345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cai M, Chen T, Quirion R, Hong Y. The involvement of spinal bovine adrenal medulla 22-like peptide, the proenkephalin derivative, in modulation of nociceptive processing. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:1128–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cai Q, Jiang J, Chen T, Hong Y. Sensory neuron-specific receptor agonist BAM8-22 inhibits the development and expression of tolerance to morphine in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2007;178:154–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Callaghan B, Haythornthwaite A, Berecki G, Clark RJ, Craik DJ, Adams DJ. Analgesic alpha-conotoxins Vc1. 1 and Rg1A inhibit N-type calcium channels in rat sensory neurons via GABAB receptor activation. J Neurosci. 2008;28:10943–51. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3594-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caterina MJ, Leffler A, Malmberg AB, Martin WJ, Trafton J, Petersen-Zeitz KR, Koltzenburg M, Basbaum AI, Julius D. Impaired nociception and pain sensation in mice lacking the capsaicin receptor. Science. 2000;288:306–13. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5464.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaplan SR, Bach FW, Pogrel JW, Chung JM, Yaksh TL. Quantitative assessment of tactile allodynia in the rat paw. J Neurosci Methods. 1994;53:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(94)90144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen H, Ikeda SR. Modulation of ion channels and synaptic transmission by a human sensory neuron-specific G-protein-coupled receptor, SNSR4/mrgX1, heterologously expressed in cultured rat neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24:5044–53. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0990-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen T, Hu Z, Quirion R, Hong Y. Modulation of NMDA receptors by intrathecal administration of the sensory neuron-specific receptor agonist BAM8-22. Neuropharmacology. 2008;54:796–803. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi SS, Lahn BT. Adaptive evolution of MRG, a neuron-specific gene family implicated in nociception. Genome Res. 2003;13:2252–9. doi: 10.1101/gr.1431603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chung C, Carteret AF, McKelvy AD, Ringkamp M, Yang F, Hartke TV, Dong X, Raja SN, Guan Y. Analgesic properties of loperamide differ following systemic and local administration to rats after spinal nerve injury. Eur J Pain. 2012;16:1021–32. doi: 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2012.00148.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Costigan M, Woolf CJ. No DREAM, No pain. Closing the spinal gate Cell. 2002;108:297–300. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00640-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delmas P, Abogadie FC, Buckley NJ, Brown DA. Calcium channel gating and modulation by transmitters depend on cellular compartmentalization. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:670–8. doi: 10.1038/76621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dixon WJ. Efficient analysis of experimental observations. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1980;20:441–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.20.040180.002301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dong X, Han S, Zylka MJ, Simon MI, Anderson DJ. A diverse family of GPCRs expressed in specific subsets of nociceptive sensory neurons. Cell. 2001;106:619–32. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00483-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grazzini E, Puma C, Roy MO, Yu XH, O’Donnell D, Schmidt R, Dautrey S, Ducharme J, Perkins M, Panetta R, Laird JM, Ahmad S, Lembo PM. Sensory neuron-specific receptor activation elicits central and peripheral nociceptive effects in rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:7175–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307185101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guan Y, Johanek LM, Hartke TV, Shim B, Tao YX, Ringkamp M, Meyer RA, Raja SN. Peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor agonist attenuates neuropathic pain in rats after L5 spinal nerve injury. Pain. 2008;138:318–29. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guan Y, Liu Q, Tang Z, Raja SN, Anderson DJ, Dong X. Mas-related G-protein-coupled receptors inhibit pathological pain in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:15933–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011221107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guan Y, Yuan F, Carteret AF, Raja SN. A partial L5 spinal nerve ligation induces a limited prolongation of mechanical allodynia in rats: an efficient model for studying mechanisms of neuropathic pain. Neurosci Lett. 2010;471:43–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hager UA, Hein A, Lennerz JK, Zimmermann K, Neuhuber WL, Reeh PW. Morphological characterization of rat Mas-related G-protein-coupled receptor C and functional analysis of agonists. Neuroscience. 2008;151:242–54. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.09.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han L, Ma C, Liu Q, Weng HJ, Cui Y, Tang Z, Kim Y, Nie H, Qu L, Patel KN, Li Z, McNeil B, He S, Guan Y, Xiao B, LaMotte RH, Dong X. A subpopulation of nociceptors specifically linked to itch. Nat Neurosci. 2012 doi: 10.1038/nn.3289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han SK, Dong X, Hwang JI, Zylka MJ, Anderson DJ, Simon MI. Orphan G protein-coupled receptors MrgA1 and MrgC11 are distinctively activated by RF-amide-related peptides through the Galpha q/11 pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:14740–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192565799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hong Y, Dai P, Jiang J, Zeng X. Dual effects of intrathecal BAM22 on nociceptive responses in acute and persistent pain--potential function of a novel receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;141:423–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang F, Wang X, Ostertag EM, Nuwal T, Huang B, Jan YN, Basbaum AI, Jan LY. TMEM16C facilitates Na(+)-activated K(+) currents in rat sensory neurons and regulates pain processing. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1284–90. doi: 10.1038/nn.3468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiang J, Wang D, Zhou X, Huo Y, Chen T, Hu F, Quirion R, Hong Y. Effect of Mas-related gene (Mrg) receptors on hyperalgesia in rats with CFA-induced inflammation via direct and indirect mechanisms. Br J Pharmacol. 2013 doi: 10.1111/bph.12326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Julius D, Basbaum AI. Molecular mechanisms of nociception. Nature. 2001;413:203–10. doi: 10.1038/35093019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim KJ, Yoon YW, Chung JM. Comparison of three rodent neuropathic pain models. Exp Brain Res. 1997;113:200–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02450318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kunapuli P, Lee S, Zheng W, Alberts M, Kornienko O, Mull R, Kreamer A, Hwang JI, Simon MI, Strulovici B. Identification of small molecule antagonists of the human mas-related gene-X1 receptor. Anal Biochem. 2006;351:50–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2006.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kusudo K, Ikeda H, Murase K. Depression of presynaptic excitation by the activation of vanilloid receptor 1 in the rat spinal dorsal horn revealed by optical imaging. Mol Pain. 2006;2:8. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lembo PM, Grazzini E, Groblewski T, O’Donnell D, Roy MO, Zhang J, Hoffert C, Cao J, Schmidt R, Pelletier M, Labarre M, Gosselin M, Fortin Y, Banville D, Shen SH, Strom P, Payza K, Dray A, Walker P, Ahmad S. Proenkephalin A gene products activate a new family of sensory neuron--specific GPCRs. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:201–9. doi: 10.1038/nn815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li L, Cao XH, Chen SR, Han HD, Lopez-Berestein G, Sood AK, Pan HL. Up-regulation of Cavbeta3 subunit in primary sensory neurons increases voltage-activated Ca2+ channel activity and nociceptive input in neuropathic pain. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:6002–13. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.310110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu Q, Tang Z, Surdenikova L, Kim S, Patel KN, Kim A, Ru F, Guan Y, Weng HJ, Geng Y, Undem BJ, Kollarik M, Chen ZF, Anderson DJ, Dong X. Sensory neuron-specific GPCR Mrgprs are itch receptors mediating chloroquine-induced pruritus. Cell. 2009;139:1353–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu Y, Yang FC, Okuda T, Dong X, Zylka MJ, Chen CL, Anderson DJ, Kuner R, Ma Q. Mechanisms of compartmentalized expression of Mrg class G-protein-coupled sensory receptors. J Neurosci. 2008;28:125–32. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4472-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luo MC, Zhang DQ, Ma SW, Huang YY, Shuster SJ, Porreca F, Lai J. An efficient intrathecal delivery of small interfering RNA to the spinal cord and peripheral neurons. Mol Pain. 2005;1:29. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-1-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.MacDermott AB, Role LW, Siegelbaum SA. Presynaptic ionotropic receptors and the control of transmitter release. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1999;22:443–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.22.1.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ndong C, Pradhan A, Puma C, Morello JP, Hoffert C, Groblewski T, O’Donnell D, Laird JM. Role of rat sensory neuron-specific receptor (rSNSR1) in inflammatory pain: contribution of TRPV1 to SNSR signaling in the pain pathway. Pain. 2009;143:130–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park U, Vastani N, Guan Y, Raja SN, Koltzenburg M, Caterina MJ. TRP vanilloid 2 knock-out mice are susceptible to perinatal lethality but display normal thermal and mechanical nociception. J Neurosci. 2011;31:11425–36. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1384-09.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pernia-Andrade AJ, Kato A, Witschi R, Nyilas R, Katona I, Freund TF, Watanabe M, Filitz J, Koppert W, Schuttler J, Ji G, Neugebauer V, Marsicano G, Lutz B, Vanegas H, Zeilhofer HU. Spinal endocannabinoids and CB1 receptors mediate C-fiber-induced heterosynaptic pain sensitization. Science. 2009;325:760–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1171870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raja SN, Haythornthwaite JA. Combination therapy for neuropathic pain--which drugs, which combination, which patients? N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1373–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe058039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scholz J, Woolf CJ. Can we conquer pain? Nat Neurosci. 2002;5 (Suppl):1062–7. doi: 10.1038/nn942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sikand P, Dong X, LaMotte RH. BAM8-22 peptide produces itch and nociceptive sensations in humans independent of histamine release. J Neurosci. 2011;31:7563–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1192-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ueno S, Yamada H, Moriyama T, Honda K, Takano Y, Kamiya HO, Katsuragi T. Measurement of dorsal root ganglion P2X mRNA by SYBR Green fluorescence. Brain Res Brain Res Protoc. 2002;10:95–101. doi: 10.1016/s1385-299x(02)00187-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang D, Chen T, Yang J, Couture R, Hong Y. Activation of Mas-related gene (Mrg) C receptors enhances morphine-induced analgesia through modulation of coupling of mu-opioid receptor to Gi-protein in rat spinal dorsal horn. Neuroscience. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.08.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wei F, Guo W, Zou S, Ren K, Dubner R. Supraspinal glial-neuronal interactions contribute to descending pain facilitation. J Neurosci. 2008;28:10482–95. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3593-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilson SR, Gerhold KA, Bifolck-Fisher A, Liu Q, Patel KN, Dong X, Bautista DM. TRPA1 is required for histamine-independent, Mas-related G protein-coupled receptor-mediated itch. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:595–602. doi: 10.1038/nn.2789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zeng X, Huang H, Hong Y. Effects of intrathecal BAM22 on noxious stimulus-evoked c-fos expression in the rat spinal dorsal horn. Brain Res. 2004;1028:170–9. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zylka MJ, Dong X, Southwell AL, Anderson DJ. Atypical expansion in mice of the sensory neuron-specific Mrg G protein-coupled receptor family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:10043–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1732949100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]