Abstract

Umbilical cord blood (UCB)-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have been introduced as a possible therapy in acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). This case history is reported of a 59-yr-old man who was treated with MSCs in the course of ARDS and subsequent pulmonary fibrosis. He received a long period of mechanical ventilation and weaning proved difficult. On hospital day 114, he underwent the intratracheal administration of UCB-derived MSCs at a dose of 1 × 106/kg. After cell infusion, an immediate improvement was shown in his mental status, his lung compliance (from 22.7 mL/cmH2O to 27.9 mL/cmH2O), PaO2/FiO2 ratio (from 191 mmHg to 334 mmHg) and his chest radiography over the course of three days. Even though he finally died of repeated pulmonary infection, our current findings suggest the possibility of using MSCs therapy in an ARDS patient. It is the first clinical case of UCB-derived MSCs therapy ever reported.

Keywords: Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome, Acute Lung Injury, Stem Cells, Therapy

INTRODUCTION

While the recent strategies of lung-protective ventilation and proper fluid restriction therapy have reduced mortality in patients with acute lung injury (ALI) and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), the mortality rate remains high. Although many pharmacological therapies have been attempted to treat ALI/ARDS, no specific therapy has demonstrated a clear effect so far. Accordingly, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have been introduced as a possible therapy. MSCs are multipotent adult stem cells that have the ability to differentiate into many different cell lineages and the capacity for self-renewal (1). In early research on the use of MSCs to treat ALI/ARDS, the main mechanism of action of these cells seemed likely to involve the replacement of injured lung epithelium. However, subsequent studies have suggested that the most important therapeutic effect probably comes from the paracrine properties of MSCs (2, 3).

Thus far, the therapeutic potentials of MSCs have primarily been supported by preclinical evidence and the need for clinical trials has been suggested (4). As there is a lack of clinical data, we here introduce a patient who was treated with MSCs in the course of ARDS and subsequent pulmonary fibrosis.

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 59-yr-old man with a history of pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) and no significant family history was diagnosed with idiopathic thrombocytopenia in June 2008. The patient was treated with corticosteroid therapy. In October 2008, he developed a cough, sputum, and rhinorrhea and five days later displayed fever and dyspnea. He was subsequently admitted to hospital. His chest radiography and computed tomography (CT) scan showed multifocal patchy ground-glass opacities (GGOs) in both lungs with underlying emphysema with large bullae in the left lower lobe and focal irregular nodular lesions in the right upper lobe that were presumed to be TB sequelae. He was assessed as having atypical pneumonia. Considering his immunocompromised status, antibiotic therapy was commenced empirically.

After five days, he was transferred to our hospital, a tertiary referral center, and admitted to the medical intensive care unit. At admission, he had tachypnea with a fever of 39℃. He had progressive bilateral diffuse infiltrations on his chest radiography. His initial SaO2 level was 75% and his PaO2/FiO2 (P/F) ratio was 166 mmHg. He was diagnosed with ARDS caused by atypical pneumonia. He then received mechanical ventilation (MV). We started a course of methylprednisolone at a dose of 40 mg twice a day to treat a possible Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia in conjunction with a continuing regimen of empirical antibiotics and an antiviral agent. However, no specific pathogen was identified in any specimen from this patient, including bronchoalveolar lavage, blood or sputum. Then, his chest radiography was stationary and his P/F ratio began to gradually improve.

On hospital day (HD) 7, he underwent tracheostomy to enable early weaning from MV. However, he then developed hospital-acquired pneumonia and hydropneumothorax due to a ruptured bullae with bronchopulmonary fistula (BPF). The repeated lung infections made him dependent on MV and weaning proved difficult. He was conscious during this time but he could not communicate with the medical team or even his family members. A psychiatrist diagnosed a hypoactive delirium due to his poor condition. On HD 87, he had a follow-up high-resolution CT, which showed aggravation of diffuse GGOs and interlobular septal thickening in both lungs. This indicated the progression of pulmonary fibrosis as a post-ARDS sequelae. After discussing the possibility of administering MSCs with his family, we commenced with a trial of this therapy.

The MSC trial was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center. The umbilical cord blood (UCB)-derived MSCs (UCB-MSCs) were prepared as follows. UCB was obtained from a full-term delivery with informed maternal consent. UCB-MSCs were produced at the Good Manufacturing Practice facility of Medipost Co., Ltd., Seoul, Korea. Quality control and quality assurance for the production of these cells were performed according to the standards of the Korea Food and Drug Administration. Flow cytometry analysis of expressed surface antigens showed that these cells were uniformly positive for CD29, CD44, CD73, CD105, and CD166 and negative for the hematopoietic lineage markers CD34, CD45, CD14, and HLA-DR. The final UCB-MSCs preparations used in the infusion were harvested from cell culture passage 6 and suspended at a final density of 7.5×106/1.5 mL in normal saline.

On HD 114, the patient underwent the intratracheal administration of UCB-MSCs at a target dose of 1×106/kg. Before the procedure, the ventilator was set to the pressure-controlled ventilation (PCV) mode of 26 cmH2O of inspiratory pressure (IP) and 0.45 of FiO2. We evenly infused 5.5×107 MSCs into both bronchi by wedging each bronchus. There were no peri-procedural complications.

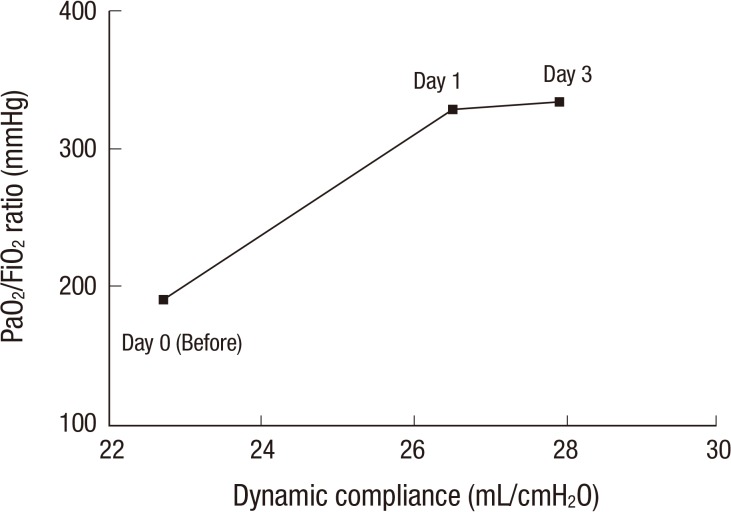

The next morning (16 hr later), he was able to communicate effectively with our medical team, which had not been possible in the previous few months. The IP was reduced to 24 cmH2O with 0.4 of FiO2. After 24 hr, we changed the PCV to a pressure support mode with 18 cmH2O of support pressure with 0.4 of FiO2. After 48 hr, PCV was applied again with 22 cmH2O with 0.35 of FiO2. The dynamic compliance of his lung improved from a pre-procedure value of 22.7 to 26.5, 27.3, and 27.9 mL/cmH2O after 24, 48, and 72 hr, respectively. His P/F ratio subsequently increased from pre-procedural 191 to 328 mmHg on day 1 after the procedure and to 334 mmHg on day 3 (Fig. 1). A follow-up chest radiography showed a slight decrease in bilateral lung infiltrates (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

The interval changes of the physiologic parameters. The interval change of the dynamic compliance and PaO2/FiO2 ratio before (day 0) and after (day 1 and day 3) the intratracheal administration of umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells. After the injection, subsequent dynamic compliance and P/F ratio showed a marked improvement.

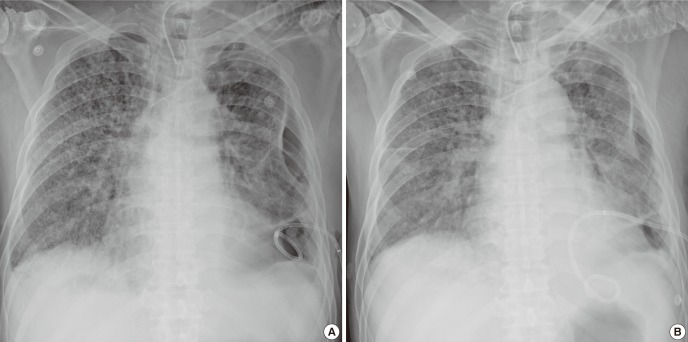

Fig. 2.

Radiologic images before and after stem cell administration. A slight improvement was shown between day 0 (A) and day 3 (B).

On day 3, however, he suddenly experienced six generalized tonic-clonic seizures during the course of the day with a fever near to 39℃. He had no focal lateralizing signs. A brain CT was performed and showed no hemorrhage. His electroencephalogram showed no abnormal epileptiform discharge. We discussed the case with neurological specialists and determined that the current use of carbapenem was the most probable cause of his seizure. We discontinued it and started him on an anticonvulsant. Subsequently, he had no more seizures.

The weaning trial was restarted for our patient and the IP was reduced to 12 cmH2O with 0.3 of FiO2 during the following week. However, he could not be weaned because his repeated infection by multidrug-resistant pathogens was not controlled. Eventually, he suffered septic shock due to empyema and died on HD 231 or day 118 after MSC administration.

DISCUSSION

Our current case involved a patient who developed ARDS due to pneumonia. He subsequently had post-ARDS pulmonary fibrosis. Weaning from MV was difficult as he did not improve for a long-period (four months). Although he failed to survive, his immediate improvement after cell infusion is worthy of mention. His mental status, his lung compliance, P/F ratio and his chest radiography all showed improvement over the course of at least three days. We speculate that these clinical, physiological and radiological improvements might be related to the paracrine properties of MSCs, with immunomodulation, alveolar fluid clearance and regulation of lung protein permeability known as potential mechanisms (2).

The main reasons for our failure to help this patient survive by MSCs therapy are likely to be the following. First, his pulmonary fibrosis was so advanced that it could not respond to the stem cell therapy. Its effectiveness may depend mainly on paracrine activity rather than regeneration by stem cell engraftment. Thus, a long-term effect would not be expected due to his advanced stage of fibrosis. Second, his BPF-related repeat infections may have caused the lack of improvement in his lung compliance. Since the pathogens that were responsible for the infection were multidrug-resistant to current antibiotics, a proper antimicrobial treatment could not be performed in advance of the stem cell therapy.

A third possible reason concerns the dose and the number of stem cells administered. We intratracheally infused 1×106/kg stem cells on one occasion but no study regarding the proper number of cells for intrapulmonary administration in humans has thus far been reported. Accordingly, our dose was based on that used intravenously in a trial in acute graft-versus-host-disease after allogeneic hematologic stem cell transplantation (5). We decided to infuse using a local route as we expected more intrapulmonary action and less systemic adverse effects than for an intravenous injection. However, our dose or the one-time-only administration may have been insufficient to produce a significant effect.

This report has a number of notable limitations that hinder the interpretation of the definite effect of MSCs in post-ARDS pulmonary fibrosis. First, we did not check the level of cytokines or other soluble factors that have been shown to be associated with the functions of MSCs in preclinical studies. In addition, our interpretation in this case study relied on clinical parameters and radiological images only. Thus, it is difficult to precisely link the patient's short-term clinical improvement to the definite action of the MSCs. Finally, even though the clinical studies of MSC therapy for acute lung injury are currently underway, there is no definite evidence so far. Thus, our decision on the MSC therapy may have some ethical problems although we had no other way as a salvage therapy for his fibrotic stage of ARDS.

Our current findings suggest the possibility of using MSC therapy in an ARDS patient and it is the first clinical case of UCB-MSCs therapy ever reported. For a clear verification of MSC therapy in ALI, future clinical trials are required.

Footnotes

This work was performed at Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea.

References

- 1.Loebinger MR, Janes SM. Stem cells for lung disease. Chest. 2007;132:279–285. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee JW, Fang X, Krasnodembskaya A, Howard JP, Matthay MA. Concise review: mesenchymal stem cells for acute lung injury: role of paracrine soluble factors. Stem Cells. 2011;29:913–919. doi: 10.1002/stem.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matthay MA, Goolaerts A, Howard JP, Lee JW. Mesenchymal stem cells for acute lung injury: preclinical evidence. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(10 Suppl):S569–S573. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181f1ff1d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mac Sweeney R, McAuley DF. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy in acute lung injury: is it time for a clinical trial? Thorax. 2012;67:475–476. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-201309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Le Blanc K, Frassoni F, Ball L, Locatelli F, Roelofs H, Lewis I, Lanino E, Sundberg B, Bernardo ME, Remberger M, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of steroid-resistant, severe, acute graft-versus-host disease: a phase II study. Lancet. 2008;371:1579–1586. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60690-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]