Abstract

Aims

To examine relationships between characteristics of the local alcohol environment and adolescent alcohol use and beliefs in 50 California cities.

Design

The study used longitudinal survey data collected from adolescents; city-level measures of local alcohol policy comprehensiveness, policy enforcement, adult drinking, and bar density; and multi-level modeling with three levels (city, individual, time), allowing for random effects. Models included interaction terms (time × alcohol environment characteristics) and main effects, controlling for city and youth demographic characteristics. Analyses also examined possible mediating effects of alcohol-related beliefs.

Setting

50 California cities (50,000 – 500,000 population).

Participants

Random samples of 1,478 adolescents and 8,553 adults.

Measurements

Past-year alcohol use and heavy drinking, and alcohol-related beliefs (e.g., perceived alcohol availability) among adolescents; past-28-day alcohol use among adults; ratings of local alcohol control policies; funding for enforcement activities; bars per roadway mile.

Findings

Local alcohol policy comprehensiveness and enforcement were associated with lower levels of past-year alcohol use (betas = −.003 and −.085, p<.05). Bar density was associated with a higher level of past-year alcohol use (beta = 1.09, p<.01). A greater increase in past-year alcohol use and heavy drinking over time was observed among adolescents living in cities with higher levels of adult drinking (betas = .224 and .108, p<.01). Effects of bar density appeared to be mediated through perceived alcohol availability and perceived approval of alcohol use.

Conclusions

Adolescent alcohol use and heavy drinking are related to characteristics of the local alcohol environment, including alcohol control policies, enforcement, adult drinking, and bar density. Change in adolescents’ drinking appears to be influenced by community-level adult drinking. Bar density effects appear to be mediated through perceived alcohol availability and approval of alcohol use.

Introduction

Despite a minimum legal drinking age of 21, hazardous drinking and alcohol-related problems such as drinking and driving remain prevalent among adolescents in the U.S. For example, the 2012 Monitoring The Future (MTF) Survey indicated that 11% of 8th graders, 27.6% of 10th graders, and 41.5% of 12th graders had consumed at least one alcoholic drink in the past 30 days, while prevalence rates for “binge” drinking (5+ consecutive drinks) in the past two weeks were 5.1%, 15.6%, and 23.7% among youth in these three grades, respectively [1]. The 2012 MTF Survey also indicated that 57.5% of 8th graders, 78.2% of 10th graders and 90.6% of 12th graders thought alcoholic beverages would be “fairly easy” or “very easy” to get.

The local alcohol environment may be an important point of intervention to prevent and reduce underage drinking. There is considerable variability in local alcohol control policies, enforcement, alcohol availability, and drinking norms; these characteristics have been associated with sources of alcohol used by adolescents, alcohol-related beliefs (e.g., perceived availability of alcohol) and adolescents’ drinking [2-6]. Much of the responsibility for enforcing alcohol policies relating to underage drinking falls to local communities. Local policies and enforcement efforts are frequently advocated as best practices to reduce youth access to alcohol, alcohol use, and related problems [7-9]. However, research on effects of the local alcohol environment on adolescents’ drinking is limited, particularly with respect to how the alcohol environment may affect change in adolescents’ drinking over time and possible mediating effects of alcohol-related beliefs.

A recent study of eight types of alcohol policies in 50 California cities found substantial variation in the presence and stringency of policies such as conditional use permits to regulate alcohol sales at licensed establishments, social host ordinances to reduce provision of alcohol to youth in private settings, and storefront and billboard alcohol advertising restrictions [6]. A subsequent study in the 50 cities also found considerable variation in the level of policy enforcement as indicated by funds received by city police departments from the California Alcohol Beverage Control (CA ABC) agency for enforcement of underage drinking laws [5]. Per capita funds received from CA ABC was inversely related to past-year drinking in a cohort of adolescents sampled in the 50 cities, whereas neither the presence nor stringency of the eight alcohol policies was associated with adolescents’ drinking.

Paschall et al. [5] also investigated possible effects of adult drinking and alcohol outlet density on adolescents’ drinking in the 50 cities. These community-level indicators of drinking norms and alcohol availability were positively related to past-year alcohol use and heavy drinking among adolescents. Additional analyses provided evidence for a mediating role of adolescents’ alcohol-related beliefs, including perceived approval of alcohol use, perceived availability of alcohol, and perceived enforcement of underage drinking laws. However, based on two waves of survey data collected from the adolescents, no evidence was found for effects of local alcohol environment characteristics on changes in adolescents drinking over a two-year period. This may have been due to relatively low levels of past-year alcohol use and heavy drinking in the cohort of adolescents, and limited statistical power. The present study includes a third wave of survey data, allowing for further investigation of possible effects of the local alcohol environment on adolescents’ drinking over a three-year period.

Based on social-ecological models of behavior [10], we hypothesized that increase in adolescent alcohol use and heavy drinking over the three-year period would be greater in communities with higher levels of adult drinking and licensed outlet density. Conversely, we expected increases in drinking to be lower in communities with more comprehensive and stringent alcohol control policies and higher levels of enforcement. Based on cognitive social learning theories [11, 12], we also hypothesized that effects of the local alcohol environment on adolescents’ drinking would be at least partially mediated through alcohol-related beliefs including perceived approval of alcohol use, perceived availability of alcohol, and perceived enforcement of underage drinking laws.

Methods

Study sample and survey methods

Sample of cities

The study included youth who participated in up to three waves of a longitudinal survey in a geographically diverse sample of 50 non-contiguous California cities (population range: 50,000 and 500,000). The sampling procedures for the 50 cities are described elsewhere in detail [13].

Survey methods and youth sample

Households within each city were randomly sampled from a purchased list of telephone numbers and addresses. An invitation letter describing the study and inviting participation was mailed to sampled households followed by a telephone contact. Interviewers obtained parental consent followed by assent from the youth respondents. Respondents received $25 at Waves 1 and 2 and $35 at Wave 3 as compensation for their participation in the study. Institutional review board approval was obtained prior to any data collection.

Youth were surveyed through computer-assisted telephone interviews in 2009 (Wave 1), 2010 (Wave 2) and 2011 (Wave 3). Of 3,062 households with eligible respondents, 1,543 (50.4%) participated in Wave 1, and of these youth, 1,312 (85%) participated in Wave 2, and 1,121 (73%) in Wave 3. The current study includes 1,478 youth who (1) participated in at least one wave of data collection, (2) lived in the same city across study years, and (3) provided complete data for all demographic measures. Including all youth who completed at least one wave of the survey in the analyses increases power and reduces biases related to attrition, especially when respondent loss is not random [14]. An average of 30 youths (range: 20-47, SD=5.97) were interviewed in each city. Sample characteristics are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics

| Variables | % or mean (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|

| City level (N=50) | ||

| Alcohol environment | ||

| Alcohol policy | 14.64 (7.48) | 4-30 |

| Local enforcement of underage drinking lawsa | .14 (.26) | 0-1.01 |

| Bar density | .054 (.04) | 0-.16 |

| Adult alcohol usea | .45 (.16) | .14-.76 |

| City demographics | ||

| Population density | 4870.05 (3347.54) | 1337.24-22330.15 |

| Percent under 18 years old | 23.74 (3.21) | 17.04-30.03 |

| Socioeconomic status | .00 (1.00) | −1.73-1.71 |

| Percent White | 79.19 (14.53) | 33.54-97.95 |

| Percent African-American | 5.32 (6.29) | .55-33.52 |

| Percent Hispanic | 34.17 (20.23) | 8.20-97.43 |

| Individual level (N=1,478) | ||

| Age | 14.71 (1.06) | 13-17 |

| Male | 52.2 | |

| Hispanic | 20.7 | |

| White | 67.5 | |

| Observation level | ||

| Wave 1 (N=1,478) | ||

| Past-year alcohol usea | .19 (.48) | 0-2.92 |

| Past-year heavy drinkinga | .06 (.23) | 0-1.85 |

| Perceived alcohol availabilityb | 2.35 (1.06) | 1-4 |

| Perceived enforcement of underage drinking lawsb | 3.31 (.53) | 1-4 |

| Perceived parental approval of alcohol useb | 1.12 (.36) | 1-4 |

| Wave 2 (N=1,248) | ||

| Past-year alcohol usea | .36 (.64) | 0-3.04 |

| Past-year heavy drinkinga | .12 (.33) | 0-2.16 |

| Perceived alcohol availabilityb | 2.62 (1.02) | 1-4 |

| Perceived enforcement of underage drinking lawsb | 3.26 (.52) | 1-4 |

| Perceived parental approval of alcohol useb | 1.18 (.40) | 1-4 |

| Wave 3 (N=1,061) | ||

| Past-year alcohol usea | .58 (.79) | 0-4.18 |

| Past-year heavy drinkinga | .18 (.40) | 0-2.18 |

| Perceived alcohol availabilityb | 2.70 (.99) | 1-4 |

| Perceived enforcement of underage drinking lawsb | 3.24 (.55) | 1.33-4 |

| Perceived parental approval of alcohol useb | 1.25 (.47) | 1-4 |

Mean (SD) of log transformed variable

Mean (SD) of 1-4 point response scale

Youth Survey Measures

Adolescent alcohol use and heavy drinking

Respondents were asked, “Have you ever had a whole drink (not just a sip or a taste) of an alcoholic beverage? A whole drink is a bottle or can of beer, malt liquor, or flavored malt beverage, a glass of wine, a shot of liquor, or a whole mixed drink.” Respondents who answered “yes” were then asked, “In the past 12 months, on how many days did you have a whole drink of an alcoholic beverage?” and “In the past 12 months, on the days when you drank alcohol, how many drinks did you typically have?” Response values for these two variables were multiplied to create a past-year alcohol frequency × quantity measure. Respondents who indicated any past-year drinking were also asked “In the past 12 months, on the X days when you drank, on how many of these days would you say you had five or more drinks?” The drinking variables were log transformed to reduce skewness. Frequency × quantity and heavy drinking measures have had good test-retest reliability and validity in studies with adolescents [15].

Perceived availability of alcohol

Respondents were asked, “Suppose you wanted to obtain alcoholic beverages. Overall, how easy or difficult would it be for you to get them?” Four possible response options ranged from “Very easy (1),” to “Very difficult (4).” We reverse coded response values so that a higher value represented greater perceived access to alcohol.

Perceived enforcement of underage drinking laws

Respondents were asked about the perceived likelihood of being caught by police in six situations: (1) trying to buy alcohol, (2) drinking at a party, (3) drinking in a public place, (4) driving after having 1-2 drinks, (5) driving after having too much to drink, (6) riding or driving around in a car while drinking alcohol. Four possible response options ranged from “Very unlikely (1),” to “Very likely (4).” A mean score was computed for each respondent, with a higher score indicating greater perceived enforcement of underage drinking laws (α = 0.74).

Perceived approval of alcohol use

Respondents were asked, “How much do you think your mother or female guardian would disapprove or approve if you were to have three or four whole drinks in a row?” and “How much do you think your father or male guardian would disapprove or approve if you were to have three or four whole drinks in a row?” Four possible response options ranged from “Strongly disapprove (1)” to “Strongly approve (4)”. The correlation between these two items was 0.57 (p < .01). A mean value was computed with a higher value representing greater perceived approval of alcohol use. In cases where data were provided for only one parent, the response for that parent was used.

Youth demographics

Youth reported their gender, age, race, and ethnicity. Race and ethnicity were treated as dichotomous variables (i.e., White versus non-White, Hispanic versus non-Hispanic).

Community-Level Measures

Local alcohol policies

Based on research and recommendations for best practices to reduce underage drinking [7-9], eight local alcohol policy topics were selected:

Conditional use permit (CUP) required for new establishments selling or serving alcohol (e.g., designating hours of operation, type of alcoholic beverages that can be served, outdoor lighting requirements);

Deemed approved (DA) requirements that preexisting establishments selling or serving alcohol now comply with a set of minimum operating standards;

Outdoor advertising/billboards of alcoholic beverages prohibited or limited;

Public drinking prohibited or limited;

Responsible beverage service (RBS) training required for staff of establishments selling or serving alcohol;

Social host policies mandating criminal and/or civil sanctions of hosts of underage drinking parties;

Special outdoor events policies governing alcohol service and consumption at such events (e.g., street fair);

Window advertising of alcoholic beverages prohibited or limited.

Local alcohol policy data were obtained in 2009 from city ordinances available online and interviews with City Clerks. Policy ratings are based on recent work by Fell et al. [16,17] who developed a coding scheme to assess the strength of 16 U.S. state-level underage drinking laws. For each policy topic, a city received a +1 if it had the relevant type of ordinance in question; a 0 if no such law existed. Then each element of law is assigned points for comprehensiveness and stringency or the reverse in cases in which individual provisions limit the law. These policy scores were then summed to represent local alcohol policy comprehensiveness and strength in each city [6].

Local enforcement activities

The level of proactive enforcement of underage drinking laws by local police departments in California cities is determined to some extent by funding from the California Alcohol Beverage Control Agency (CA ABC). Therefore, we used total funds received from the CA ABC in 2008-09, 2009-10, and 2010-11 as a surrogate measure of enforcement activities. Fifteen of the 50 cities received CA ABC funds in at least one of those years, ranging from $11,500-$200,000. These funds are typically used for enforcement activities such as compliance checks to reduce alcohol sales to underage youth, enforcement of minor in possession laws, cops-in-shops programs targeting youth purchase, and shoulder tap operations targeting adults purchasing alcohol for minors. To account for variation in city population size, which could influence level of funding, the per capita funding rate was computed. Because of the skewed distribution, this variable was log transformed.

Bar density

Based on records of licensed establishments obtained from the CA ABC, we computed outlet densities for bars based on the number of outlets per roadway mile. This measure is thought to be a better indicator of access to alcohol outlets than outlets per square mile [2].

Adult alcohol use

A random digit dial household telephone survey of 8,553 adults in the 50 cities was conducted in 2009 to assess levels of alcohol consumption and related problems [18]. The number of adult respondents per city ranged from 109 to 204 (mean = 171); respondents’ age ranged from 18 to 98 (mean = 54.6); 57% were female and 59% were white. The survey included a graduated frequency measure that was used to calculate the total volume and frequency of alcohol use in the past 28 days. The mean level of past-28-day adult alcohol use was then obtained for each city. This variable was log transformed to reduce skewness.

City demographics

City demographics were obtained from 2010 GeoLytics data [19]and included population density (i.e., population per square mile), % < 18 years old, and % White, African-American, and Hispanic. A socioeconomic status (SES) factor score was derived from median family income, % of population with a college education, and % of population unemployed. These measures were significantly correlated (r = .52-.79, p < .01). Principal components analysis yielded a single-factor solution, accounting for 75.1% of the variance (factor loadings range: .78-.91).

Data analysis

Attrition analyses were conducted to determine whether youth who participated in all three interviews differed from those who only participated in Wave 1 with respect to demographic characteristics and past-year drinking at Wave 1.

Multi-level linear regression analyses were conducted with HLM version 7.0 software [20] to examine associations between city-level alcohol environment measures and youth drinking behaviors and beliefs. The proportion of between-cities variance in drinking behaviors (i.e., intraclass correlations [ICCs]) was .009 and .154 for past-year alcohol use and heavy drinking, respectively. The ICCs for perceived availability, perceived enforcement, and perceived parental approval of alcohol use were .026, .0032 and .004, respectively.

Alcohol environment measures and city demographics were included as city-level variables in all models (level 3). Youth gender, age, race and ethnicity were included as individual-level variables in all models (level 2). Drinking behaviors, drinking beliefs and a time (survey wave) variable were included at the observation level (level 1). Random intercepts were included at levels 2 and 3, and a random effects term for residual variance was included at level 1. Cross-level interactions between the four alcohol environment measures and time were examined to determine whether they were predictive of outcome slopes (change), allowing for random effects. Interaction terms were dropped from the model if not statistically significant. Analyses also examined the main effects of alcohol environment measures on youth drinking behaviors and beliefs. Finally, we examined possible mediating effects of youth drinking beliefs.

Results

Sample attrition

Attrition analyses indicated that the percentage of male did not differ significantly across the three waves (range: 50.8-52.2%), while the percentage of white increased somewhat from 67.5% in Wave 1 to 71.2% in Wave 2 and 71.7% in Wave 3. Wave 1 mean levels of past-year alcohol use and heavy drinking were similar among youth who did and did not participate in Wave 2, but were significantly higher among youth who did not participate in Wave 3 (t = 2.70, df = 1,531, p = .001 for alcohol use; t = 3.45, df = 1,531, p = .007 for heavy drinking).

Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics for study variables are provided in Table 1. Prevalence rates for past-year alcohol use were 20.2% at Wave 1, 32.2% at Wave 2, and 44.8% at Wave 3. Prevalence rates for heavy drinking were 8.2% at Wave 1, 14.6% at Wave 2, and 23.2% at Wave 3.

Alcohol environment and past-year alcohol use and heavy drinking

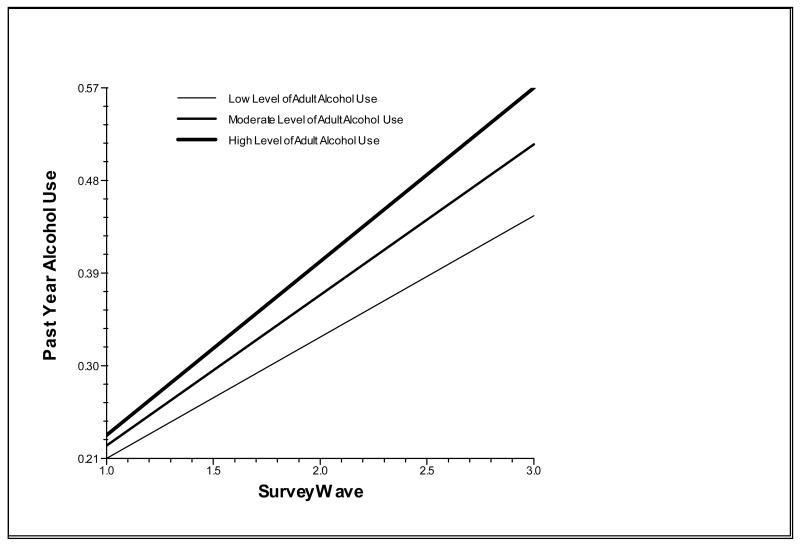

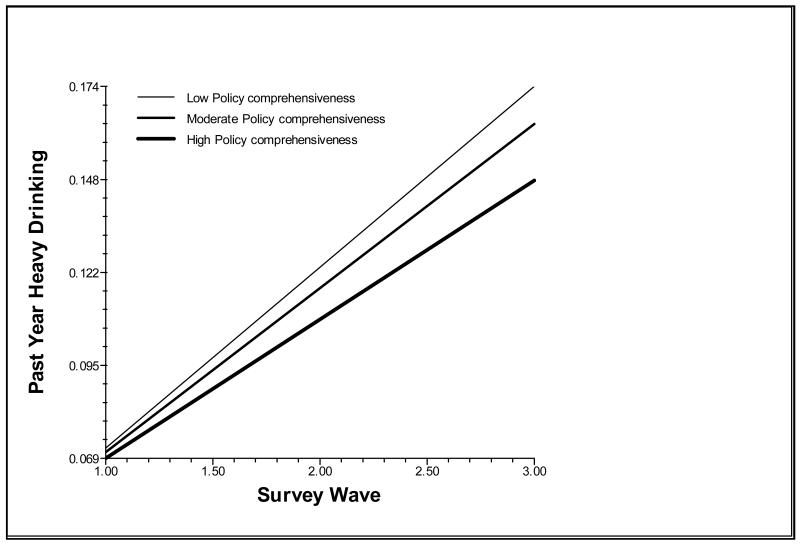

Results of multi-level analyses are in Tables 2 and 3. Statistically significant interactions were found between time and adult alcohol use for both past-year alcohol use and past-year heavy drinking in all models. These interactions indicated greater increases in drinking behaviors over time when adult drinking in the community was higher (see Figure 1). Similarly, controlling for youth- and city-level demographics and youth drinking beliefs, a marginally significant (p < .08) interaction was observed between time and alcohol policy on past-year heavy drinking. This interaction indicated that, over time, past-year heavy drinking increased to a greater extent in cities with relatively low policy comprehensiveness (see Figure 2).

Table 2.

Results of multi-level analyses of the associations between local alcohol environment and youth past-year alcohol use over time

| Predictors | Past-year alcohol use | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| City level (N=50) | ||

| Alcohol policy | −.003 (−.005, −.001)* | −.002 (−.004, .000)* |

| Local enforcement of underage drinking laws | −.085 (−.149, −.020)* | −.052 (−.103, −.001)* |

| Bar density | 1.086 (.371, 1.801)** | .357 (−.258, .972) |

| Adult alcohol use | −.110 (−.412, .192) | −.119 (−.374, .136) |

| Time × Alcohol policy | --- | --- |

| Time × Local enforcement | --- | --- |

| Time × Bar density | --- | --- |

| Time × Adult alcohol use | .224 (.084, .363)** | .213 (.093, .333)** |

| Population density | −.051 (−.076, −.026)** | −.028 (−.053, −.003)* |

| Percent under 18 years old | −.035 (−.068, −.002)* | −.038 (−.073, −.003)* |

| Socioeconomic status | .016 (−.015, .047) | .008 (−.016, .032) |

| Percent White | −.003 (−.040, .034) | −.004 (−.035, .027) |

| Percent African-American | .014 (−.008, .036) | .020 (−.002, .042) |

| Percent Hispanic | .067 (.022, .112)** | .060 (.021, .099)** |

| Individual level (N=1,478) | ||

| Age | .171 (.146, .196)** | .118 (.094, .142)** |

| Male | .114 (.069, .159)** | .089 (.054, .124)** |

| Hispanic | .105 (.003, .207)* | .081 (−.005, .167) |

| White | −.001 (−.064, .062) | −.020 (−.071, .031) |

| Observation level (N=3,785) | ||

| Perceived alcohol availability | --- | .091 (.071, .111)** |

| Perceived enforcement of underage drinking laws | --- | −.082 (−.121, −.043)** |

| Perceived parental approval of alcohol use | --- | .380 (.309, .451)** |

| Survey time | .094 (.867, 1.012)* | .050 (−.011, .111) |

p<05

p<01

Table 3.

Results of multi-level analyses of the associations between local alcohol environment and youth past-year heavy drinking over time

| Predictors | Past-year heavy drinking | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| City level (N=50) | ||

| Alcohol policy | −.001 (−.003, 001) | .001 (−.001, .003) |

| Local enforcement of underage drinking laws | −.002 (−.033, .029) | .009 (−.018, .036) |

| Bar density | .316 (−.045, .676) | .075 (−.254, .404) |

| Adult alcohol use | −.026 (−.163, .111) | −.026 (−.151, .099) |

| Time × Alcohol policy | --- | −.001 (−.003, .001)f |

| Time × Local enforcement | --- | --- |

| Time × Bar density | --- | --- |

| Time × Adult alcohol use | .108 (.034, .182)** | .105 (.032, .178)** |

| Population density | −.012 (−.024, −.000) | −.003 (−.015, .009) |

| Percent under 18 years old | −.004 (−.022, .013) | −.002 (−.019, .016) |

| Socioeconomic status | .003 (−.011, .016) | .001 (−.011, .013) |

| Percent White | −.004 (−.019, .012) | −.003 (−.015, .009) |

| Percent African-American | −.005 (−.015, .005) | −.002 (−.010, .006) |

| Percent Hispanic | .015 (−.006, .036) | .010 (−.012, .032) |

| Individual level (N=1,478) | ||

| Age | .066 (.052, .079)** | .045 (.035, .055)** |

| Male | .066 (.044, .087)** | .056 (.038, .074)** |

| Hispanic | .036 (−.009, .081) | .029 (−.012, .070) |

| White | −.006 (−.039, .027) | −.015 (−.044, .014) |

| Observation level (N=3,785) | ||

| Perceived alcohol availability | --- | .028 (.018, .038)** |

| Perceived enforcement of underage drinking laws | --- | −.045 (−.067, −.023)** |

| Perceived parental approval of alcohol use | --- | .154 (.111, .197)** |

| Survey time | .013 (−.026, .052) | .014 (−.021, .049) |

p<.05

p<.01

p=0.08

Figure 1.

Past-year alcohol use among youth over three years, by level of adult drinking in community

Figure 2.

Past-year heavy drinking among youth over three years, by comprehensiveness of local alcohol policies; the time × alcohol policy interaction was marginally significant (p=.08)

Lower alcohol policy comprehensiveness, less enforcement, and greater bar density were associated with increased past-year alcohol use (Model 1). When youth drinking beliefs were added as predictors (Model 2), the association between bar density and past-year alcohol use was no longer statistically significant.The inverse relationships between past-year drinking and alcohol policy comprehensiveness and enforcement were attenuated also, although still significant. The interactive effect of time and adult drinking was somewhat attenuated, but remained significant in models with alcohol-related beliefs. Relationships between alcohol-related beliefs and past-year alcohol use and heavy drinking were in the expected directions and statistically significant.

Alcohol environment and youth drinking beliefs

Results of multi-level analyses to examine the associations between alcohol environment measures and youth drinking beliefs are in Table 4. Bar density was positively related to perceived alcohol availability and perceived parental approval of alcohol use.

Table 4.

Results of multi-level analyses of associations between local alcohol environment and youth alcohol-related beliefs over time

| Predictors | Perceived alcohol availability |

Perceived enforcement of underage drinking laws |

Perceived parental approval of alcohol use |

|---|---|---|---|

| City level (N=50) | |||

| Alcohol policy | −.007 (−.017, .003) | .000 (−.002, .002) | −.000 (−.002, .002) |

| Local enforcement of underage drinking laws | −.059 (−.292, .174) | .085 (−.007, .177) | −.016 (−.078, .047) |

| Bar density | 4.858 (2.322, 7.394)** | −.933 (−1.862,−.004) | .925 (.374, 1.475)** |

| Adult alcohol use | .089 (−.532, .710) | .010 (−.262, .282) | −.044 (−.216, .128) |

| Time × Alcohol policy | .004 (−.000, .008)t | --- | --- |

| Time × Local enforcement | --- | --- | --- |

| Time × Bar density | −1.016 (−1.849, −.183)* | --- | --- |

| Time × Adult alcohol use | --- | --- | --- |

| Population density | −.146 (−.232, −.059)** | .041 (.006, .076)* | −.018 (−.040, .004) |

| Percent under 18 years old | .005 (−.079, .089) | .057 (.012, .102)* | .008 (−.019, .035) |

| Socioeconomic status | .063 (−.027, .153) | −.001 (−.036, .034) | .019 (−.006, .044) |

| Percent White | .019 (−.069, .107) | .025 (−.016, .066) | .004 (−.021, .029) |

| Percent African-American | −.013 (−.078, .052) | .016 (−.019, .051) | −.002 (−.023, .019) |

| Percent Hispanic | .025 (−.102, .152) | −.060 (−.114, −.010)* | .006 (−.029, .041) |

| Individual level (N=1,478) | |||

| Age | .237 (.198, .276)** | −.099 (−.119, −.079)** | .066 (.048, .084)** |

| Male | .015 (−.077, .107) | −.031 (−.074, .012) | .059 (.029, .088)** |

| Hispanic | .080 (−.092, .252) | .040 (−.032, .112) | .060 (.013, .107)* |

| White | −.013 (−.129, .103) | −.030 (−.086, .026) | .044 (.005, .083)* |

| Observation level (N=3,785) | |||

| Survey Wave | .238 (.163, .312)** | −.039 (−.053, −.025)** | .068 (.054, .082) |

p<.05

p<.01

p=0.07

this variable was log transformed

A statistically significant interaction was observed between time and alcohol policy on perceived availability of alcohol. This interaction indicated that at Wave 1, youth in cities with higher policy comprehensiveness perceived less alcohol availability compared to youth who lived in cities with lower policy comprehensiveness. However, at Wave 3, perceived availability was similar among youth who lived in cities with different levels of policy comprehensiveness. A significant interaction was also found between time and bar density on perceived alcohol availability. This interaction indicated that, at Wave 1, youth in cities with greater bar density perceived more alcohol availability compared to youth who lived in cities with lower bar density. Over time, however, levels of perceived availability in high and low density cities converged.

Discussion

Findings of this study suggest that variation in adolescents’ drinking between cities, and change in adolescents’ drinking over time, are related to characteristics of the local alcohol environment. Past-year alcohol use was inversely associated with the comprehensiveness and stringency of local alcohol policies and level of enforcement, and was positively related to bar density. A greater increase in past-year alcohol use and heavy drinking over a three-year period was observed among adolescents living in cities with higher levels of adult drinking, while a lower rate of increase in heavy drinking was observed in cities with more comprehensive and stringent alcohol control policies.

The analyses also suggest that effects of the local alcohol environment on adolescents’ drinking are at least partially mediated by alcohol-related beliefs, particularly perceived availability of alcohol and perceived parent’s approval of alcohol use. Bar density was positively related to both of these beliefs, and may therefore represent not only an indicator of alcohol availability, but also community norms regarding acceptability of alcohol use. Because underage youth are typically not allowed to go into bars or purchase alcohol, this characteristic of the local alcohol environment likely reflects adult drinking and approval of alcohol use (bar density was positively correlated with adult drinking, r = .35, p<.01).

Perceived alcohol availability increased more rapidly over the three-year period in cities with relatively low levels of bar density and high levels of alcohol policy comprehensiveness. These findings may reflect use of a broader range of commercial and social alcohol sources by adolescents as they became older, regardless of comprehensiveness and enforcement of local alcohol policies. A number of studies show greater reliance on social sources of alcohol compared to commercial sources [4,21], and this may be especially true in communities with more comprehensive and stringent alcohol policies and community norms unfavorable to drinking.

Contrary to expectations, there was no association between level of enforcement of underage drinking laws and adolescents’ perception of enforcement. This may be attributable to the fact that our measure of enforcement was limited to funds received from the California ABC. Underage drinking law enforcement activities are likely to have been occurring in cities that did not receive funds from the California ABC, but data regarding these activities are not available. Moreover, adolescents’ perceptions of enforcement may be influenced by factors other than actual levels of enforcement, such as information from friends or media coverage of enforcement activities. Perceived enforcement was inversely related to both past-year alcohol use and heavy drinking, suggesting that greater visibility of enforcement may be an effective strategy for reducing underage drinking.

Our findings should be considered in light of several possible limitations. Adolescents participating in our surveys may not be representative of all adolescents in the 50 cities, and attrition from follow-up surveys may have biased our results in some way as youth who did not participate in all three surveys reported higher levels of past-year alcohol use and heavy drinking at Wave 1. Survey responses may have been subject to recall and social desirability biases (e.g., under-reporting of alcohol use by youth who are not of legal drinking age), though measures were taken to ensure privacy and confidentiality of interviews. As noted, we relied on a proxy measure of local enforcement, which may not have captured all underage drinking enforcement activities. Therefore, our analyses may have underestimated the degree of association between level of enforcement and youth drinking.

Further research is needed to determine whether and how characteristics of the local alcohol environment may influence alcohol use among adolescents. In particular, research is needed to evaluate the effectiveness of local alcohol control policies and enforcement operations designed to reduce commercial and social availability of alcohol to youth. Little is known about the effectiveness of local policies such as social host ordinances and enforcement activities such as party dispersal operations, both of which are intended to reduce alcohol availability from social sources. Community-level studies with appropriate experimental designs are needed to evaluate the effectiveness of such strategies.

Acknowledgements

This research and preparation of this paper were supported by a grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (P60-AA006282). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIAAA or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None.

References

- 1.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2012. Volume I: Secondary school students. Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; Ann Arbor: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen M-J, Grube JW, Gruenewald PJ. Community alcohol outlet density and underage drinking. Addiction. 2010:270–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02772.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dent CW, Grube JW, Biglan A. Community level alcohol availability and enforcement of possession laws as predictors of youth drinking. Prev Med. 2005:355–362. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paschall MJ, Grube JW, Black CA, Ringwalt CL. Is commercial alcohol availability related to adolescent alcohol sources and alcohol use? Findings from a multi-level study. J Adolesc Health. 2007:168–174. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paschall MJ, Grube JW, Thomas S, Cannon C, Treffers R. Relationships between local enforcement, alcohol availability, drinking norms, and adolescent alcohol use in 50 California cities. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2012:657–665. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas S, Paschall MJ, Grube JW, Cannon C, Treffers R. [accessed on 6/26/13];Underage alcohol policies across 50 California cities: An assessment of best practices. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2012 :26. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-7-26. Available online at: http://www.substanceabusepolicy.com/content/7/1/26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention . Regulatory Strategies for Preventing Youth Access to Alcohol: Best Practices. Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation; Calverton, MD: [accessed on 6/28/13]. 1999. Available online at: http://www.udetc.org/documents/accesslaws.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention . How to Use Local Regulatory and Land Use Power to Reduce Underage Drinking. Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation; Calverton, MD: [accessed on 6/28/13]. 2000. Available online at: http://www.udetc.org/documents/regulatory.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Research Council and Institute of Medicine . Reducing Underage Drinking: A Collective Responsibility. Committee on Developing a Strategy to Reduce and Prevent Underage Drinking. Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sallis JF, Owen N, Fisher EB. Ecological models of health behavior. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, editors. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 2008. pp. 465–485. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Prentice-Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fishbein M, Hennessy M, Yzer M, Douglas J. Can we explain why some people do and some do not act on their intentions? Psychology, Health, and Medicine. 2003:3–18. doi: 10.1080/1354850021000059223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lipperman-Kreda S, Grube JW, Friend KB. Local tobacco policy and tobacco outlet density: Association with youth smoking. J Adolesc Health. 2012:547–552. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Enders CK. Applied Missing Data Analysis. Guilford; New York: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Alcohol consumption measures. In: Allen JP, Wilson VB, editors. Assessing Alcohol Problems: A Guide for Clinicians and Researchers, Second Addition. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Bethesda, MD: 2003. pp. 75–99. NIH Publication No. 03-3745. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fell JC, Fisher DA, Voas RB, Blackman K, Tippetts AS. The relationship of underage drinking laws to reductions in drinking drivers in fatal crashes in the United States. Accid Anal Prev. 2008:1430–1440. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fell JC, Fisher DA, Voas RB, Blackman K, Tippetts AS. The impact of underage drinking laws on alcohol-related fatal crashes of young drivers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009:1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00945.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gruenewald PJ, Remer LG, LaScala EA. Testing a social ecological model of alcohol use: The California 50 city study. In review Addiction. doi: 10.1111/add.12438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geolytics [accessed June 27, 2013];Official Census 2010 Data. Available online: http://www.geolytics.com/USCensus,Census%202010,Products.asp.

- 20.Raudenbush S, Bryk A, Cheong YF, Congdon R, du Toit M. HLM 7: Hierarchical Linear and Nonlinear Modeling. Scientific Software International; Lincolnwood, IL: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wagenaar AC, Toomey TL, Murray DM, Short BJ, Wolfson M, Webb-Jones R. Sources of alcohol for underage drinkers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1996:325–533. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]