Background: Coagulation factor XIIIa (FXIIIa) catalyzes cross-linking of Gln and Lys residues during coagulation.

Results: A total of 147 FXIIIa substrates were identified in human plasma, and 48 of these were incorporated into the clot.

Conclusion: These results indicate that FXIIIa is involved in extensive functionalization of the plasma clot.

Significance: We present new insights into roles of FXIIIa in physiological and pathological processes.

Keywords: Blood Coagulation Factors, Fibrinogenesis, Plasma, Proteomics, Transglutaminases

Abstract

Coagulation factor XIII (FXIII) is a transglutaminase with a well defined role in the final stages of blood coagulation. Active FXIII (FXIIIa) catalyzes the formation of ϵ-(γ-glutamyl)lysine isopeptide bonds between specific Gln and Lys residues. The primary physiological outcome of this catalytic activity is stabilization of the fibrin clot during coagulation. The stabilization is achieved through the introduction of cross-links between fibrin monomers and through cross-linking of proteins with anti-fibrinolytic activity to fibrin. FXIIIa additionally cross-links several proteins with other functionalities to the clot. Cross-linking of proteins to the clot is generally believed to modify clot characteristics such as proteolytic susceptibility and hereby affect the outcome of tissue damage. In the present study, we use a proteomic approach in combination with transglutaminase-specific labeling to identify FXIIIa plasma protein substrates and their reactive residues. The results revealed a total of 147 FXIIIa substrates, of which 132 have not previously been described. We confirm that 48 of the FXIIIa substrates were indeed incorporated into the insoluble fibrin clot during the coagulation of plasma. The identified substrates are involved in, among other activities, complement activation, coagulation, inflammatory and immune responses, and extracellular matrix organization.

Introduction

The coagulation cascade has evolved as an essential defense mechanism for maintaining hemostasis during tissue or blood vessel injury. Activation of the cascade ultimately results in the formation of an insoluble blood clot. The clot consists mainly of fibrin fibers, platelets, and red blood cells (1). The fibers are formed when activated thrombin cleaves fibrinogen into fibrin monomers, which then assemble into fibrin fibers (2). To obtain fibers that are capable of resisting mechanical shear and proteolytic degradation, concurrent cleavage of coagulation factor XIII (FXIII)3 by thrombin is needed. Once cleaved and activated, FXIIIa is able to stabilize the fibrin fibers and alter the characteristics of the clot (3). Although activation of the coagulation cascade and consequently FXIIIa is essential during blood vessel damage, it may contribute negatively in pathological situations such as sepsis and cardiovascular disease (1, 4).

FXIIIa belongs to the family of human transglutaminases (TG) (EC 2.3.2.13) (5). This group of enzymes is defined by their common ability to catalyze thiol- and Ca2+-dependent transamidation reactions (5). The TG-catalyzed reaction between specific Gln and Lys residues within substrate proteins results in the formation of covalent cross-links, defined as ϵ-(γ-glutamyl)lysine isopeptide bonds (5). The major physiological function of FXIIIa is to stabilize the fibrin clot during coagulation. FXIIIa cross-links α- and γ-chains of fibrin monomers within fibrin fibers once they have been formed. The intermolecular cross-linking of the fibrin monomers converts loose fibrin fibers into a stable fiber network that is able to withstand mechanical stress and resist clot rupture (6). FXIIIa deficiency, which causes severe bleeding diathesis, demonstrates the essential role of FXIIIa in coagulation (7).

Secondary to the cross-linking of fibrin, FXIIIa cross-links several other proteins to the clot. This secondary cross-linking functionalizes the clot as exemplified by the cross-linking of α2-antiplasmin (8). Plasmin is the main fibrinolytic protease; by cross-linking a plasmin inhibitor such as α2-antiplasmin to the fibrin fibers, FXIIIa contributes to a significant increase in clot stability. FXIIIa furthermore cross-links a number of different proteins to the clot, including factor V (9), thrombin-activable fibrinolysis inhibitor (10), von Willebrand factor (11), complement C3 (12), inter-α-inhibitor (13), and plasminogen activator inhibitor type 2 (14). These proteins could regulate clot characteristics other than stability. The cross-linking of fibronectin to fibrin by FXIIIa has, for instance, been shown to influence cell adhesion and migration in a fibrin matrix (15).

Several different methods have been employed to identify and characterize substrates of FXIIIa and TGs in general. These methods include labeling TG-reactive Gln residues with fluorescent or biotinylated compounds that contain primary amines, such as dansyl-cadaverine and 5-(biotinamido)pentylamine (BPA), and labeling TG-reactive Lys residues with labeled synthetic peptides (16). TG-specific labeling of substrates has previously been combined with affinity chromatography and mass spectrometry to identify reactive residues in TG substrates (17, 18).

In this study, we present for the first time an in depth and time-resolved analysis of the FXIIIa substrate proteome in plasma. To circumvent problems related to the wide range of protein concentrations in plasma, we developed a proteomic strategy based on a combination of chromatographic separation, FXIIIa-specific labeling, and high performance mass spectrometry. Using this strategy, we identified 147 FXIIIa substrates in plasma of which 132 were previously unknown. We furthermore accessed the relevance of these substrates by identifying the proteins that comprise the insoluble clot. We found 70 different proteins associated with the plasma clot. Of the identified clot proteins, 48 were substrates for FXIIIa, thus supporting that these are indeed physiologically relevant substrates.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Immobilized monomeric avidin was from Thermo Scientific, BPA was from Biotium, recombinant human FXIII was from Zedira (T027), and human thrombin and trypsin were purchased from Sigma.

Preparation of Plasma Samples

Blood from a healthy donor was collected into Vacutainer K2 EDTA tubes (BD Diagnostics). The plasma fraction was isolated after centrifugation at 950 rpm for 15 min. EDTA was added to the plasma sample to a final concentration of 5 mm. The plasma was centrifuged at 13200 rpm and filtered through a 0.45-μm filter before being applied to a column containing the albumin-binding domain of protein G (19). The column was equilibrated in 20 mm NaH2PO4, 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA, pH 7.2. The albumin depleted flow through was collected and dialyzed against 40 mm Tris-HCl, 5 mm EDTA, pH 7.4 (buffer A), and applied to a 5-ml HiTrapQ column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in buffer A. The column was eluted using a linear gradient of buffer B (buffer A containing 1 m NaCl) to 60% buffer B followed by a linear gradient to 100% buffer B at a flow rate of 2.5 ml/min. Eluting fractions were monitored at 280 nm and pooled according to the elution profile (five pools). All pools were dialyzed into 20 mm Tris-HCl, 137 mm NaCl, pH 7.4, and concentrated using either Centriprep centrifugal filters (Millipore) or Amicon Ultra centrifugal filters (Millipore) (molecular weight cutoff, 10 kDa). Judged by SDS-PAGE, the filtrate did not contain any proteins.

Transglutaminase-catalyzed Incorporation of 5-(Biotinamido)pentylamine

FXIII was activated by incubation with thrombin (1 milliunit of thrombin/1 μg of FXIII) in 20 mm Tris-HCl, 137 mm NaCl, pH 7.4 for 1 h at 37 °C. A total of 300 μg of protein from each of the five HiTrapQ pools was incubated with FXIIIa at a 1:25 (w/w) ratio in 20 mm Tris-HCl, 137 mm NaCl, pH 7.4, containing 10 mm CaCl2, 0.5 mm DTT, and 10 mm BPA. After an incubation period of 30, 60, or 180 min at 37 °C, the reaction was stopped by addition of EDTA to 15 mm. To identify endogenous FXIIIa activity, an identical set of control samples were incubated for 180 min without the addition of FXIIIa. All labeled samples were lyophilized using a SpeedVac (Savant) and dissolved in 100 mm Tris-HCl, 6 m guanidine HCl, pH 8, containing 10 mm DTT followed by the addition of iodoacetamide to a final concentration of 30 mm. The reduced and alkylated samples were dialyzed into 20 mm NH4HCO3. The samples were concentrated using a SpeedVac (Savant). A double digestion was performed with 2 × 1:40 (w/w) trypsin at 37 °C before addition of PMSF to a final concentration of 1 mm. The samples were lyophilized using a SpeedVac (Savant), dissolved in 100 mm NaH2PO4, 150 mm NaCl, pH 7, and applied to a monomeric avidin affinity column (Pierce) equilibrated in 100 mm NaH2PO4, 150 mm NaCl, pH 7. After extensive washing, the BPA-labeled peptides were eluted using 100 mm glycine, pH 2.8, and desalted using self-packed micro columns containing POROS R2 (Applied Biosystems) prior to LC-MS/MS analysis (20). All samples were analyzed in three separate LC-MS/MS runs.

Clot Formation and Purification

Blood was collected from healthy volunteers by fingerprick. The collected blood sample was immediately centrifuged for 1 min at 7000 × g to obtain the plasma fraction. The plasma fraction was allowed to clot for 2 h at 37 °C. To remove noncovalently bound proteins, the clot was washed three times for 20 min in each of the following buffers: 1) 20 mm Tris-HCl, 150 mm NaCl, pH 7.4; 2) 20 mm Tris-HCl, 2 m NaCl, pH 7.4; 3) 20 mm Tris-HCl, 2 m NaCl, 6 m guanidine HCl, pH 7.4; and 4) water. Finally the sample was boiled in sample buffer containing 0.1% SDS and separated by SDS-PAGE. Covalently cross-linked proteins were retained in the stacking gel and could be collected after electrophoresis. The SDS was removed by washing the gel piece in a microspin filter (molecular weight cutoff, 3 kDa) using: 1) water; 2) 50% acetonitrile containing 50 mm NH4HCO3; and finally, 3) 50 mm NH4HCO3. The sample was reduced, alkylated, and digested with trypsin for 16 h at 37 °C. The tryptic peptides were collected and micropurified using self-pack micro columns containing POROS R2 (20). The purified peptides were either analyzed by mass spectrometry directly or prefractionated by strong cation exchange. For strong cation exchange, the purified peptides were dissolved in 10 mm KH2PO4, 20% acetonitrile, pH 2.8 (Buffer A) and separated on a PolySULFOETHYL A column (PolyLC) equilibrated in buffer A. The peptides were eluted using a linear gradient of buffer B (500 mm KCL in buffer A) at 1% B/min using a flow rate of 150 μl/min. A total of 16 pools were collected and desalted using C18 StageTips (ThermoScientific) prior to LC-MS/MS.

A control sample containing 13C6Arg-labeled proteins were produced by culturing HepG2-SF cells (Cell Culture Service) in a serum-free medium composed of RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen), 10% SynQ (Cell Culture Service), 4 mm l-glutamine (Sigma), 20 units/ml penicillin (Invitrogen), and 20 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen). The medium was supplemented with leucine and lysine at final concentrations of 0.38 and 0.87 mm, respectively. Stable isotope-labeled growth medium was prepared by adding 1.15 mm 13C6Arg. The cells were cultured for five doublings and tested for full incorporation of 13C6Arg. Nunc culture flasks (75 cm2) were maintained at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. The medium was depleted for Albumin using the albumin-binding domain of protein G as described above.

The noncovalent binding of proteins to the plasma clot was investigated by preparing a clot from 100 μl of freshly drawn plasma. The clot was incubated for 3 h at 37 °C, briefly washed in 50 mm Tris-HCl, 150 mm NaCl, pH 7.4, and transferred to the stable isotope-labeled control medium containing 25 μg of labeled protein. The samples were incubated for 4 h in the presence of the FXIIIa inhibitor K9-DON (Zedira), extensively washed, run in SDS-PAGE, and digested with trypsin as described above. The samples were analyzed directly by LC-MS/MS.

Mass Spectrometry

Nano-LC-MS/MS was performed using an EASY-nLC II system (ThermoScientific) connected to a TripleTOF 5600 mass spectrometer (AB Sciex). Peptides were dissolved in 5% formic acid, injected, trapped, and desalted on a Biosphere C18 column (5 μm, 2 cm × 100-μm inner diameter; Nano Separations). The peptides were eluted from the trap column and separated on a 15-cm analytical column (75-μm inner diameter) packed in-house in a fritted silica tip (New objectives) with RP ReproSil-Pur C18-AQ 3 μm resin (Dr. Marisch GmbH, Ammerbuch-Entringen, Germany) and connected in-line to the mass spectrometer. Peptides were eluted at a flow rate of 250 nl/min, using a 50-min gradient from 5 to 35% phase B (0.1% formic acid and 90% acetonitrile). The collected MS files were converted to Mascot generic format using the AB Sciex MS data converter beta 1.1 (AB Sciex) and the protein pilot Mascot generic format parameters. The generated peak lists were searched against the Swiss-Prot database (SwissProt_2013_07 containing 20264 human protein sequences) using in-house Mascot search engine (release version 2.3.02, Matrix Science).

Search parameters used for protein identification were: Homo sapiens, trypsin, two missed cleavages, carbamidomethyl (Cys) as fixed modification, and oxidation (Met) as variable modification. For the BPA-labeled samples, the corresponding modification was selected as a variable modification (Biotin:Thermo-21345). Peptide tolerance was 15 ppm, and MS/MS tolerance was 0.3 Da.

Validation of Protein Identifications

BPA-labeled Peptides

Individual substrate sites were accepted if they were identified in all triplicate LC-MS/MS runs with a minimum peptide score of 25 or if the site was identified at least once with a minimum peptide score of 45.

Clot Proteome

We manually inspected all proteins identified by only a single peptide with peptides scores below 45. Peptide identifications were only accepted if they had three sequential y- or b-ions of high intensity.

Extracted Ion Chromatography-based Protein Quantitation

All raw MS files were processed using Mascot Distiller 2.4.3.3 (Matrix Science). The data were analyzed using the default settings from the ABSciex_5600.opt file except that the MS/MS peak picking “same as MS peak picking” was deselected, and “fit method” was set to “single peak.” A Mascot search was performed using the default average (MD) quantitation protocol. Mascot Distiller results were imported into MS Data Miner v. 1.2.1 (21). The relative abundance of proteins quantified in a minimum of three MS runs was calculated as the average MS intensity for the three most intense peptides for each protein divided by the total sum of the average signal for all quantified proteins in the sample.

RESULTS

Identification of FXIIIa Substrates

The plasma used for the identification of FXIIIa substrates was depleted of albumin and separated into five pools using anion exchange chromatography. The pools were incubated with FXIIIa in the presence of BPA and digested with trypsin. The BPA-containing peptides were extracted using immobilized monomeric avidin and subjected to LC-MS/MS analysis. Using this approach, we were able to identify both the substrates and the specific Gln residue used by FXIIIa in the transamidation reaction. A total of 147 unique proteins with at least one reactive Gln residue were identified (Table 1 and supplemental Table S1). We were able to identify 15 of 31 known human FXIIIa substrates. However, only 20 of the known substrates can be classified as plasma proteins, and of these 20 proteins, we did not identify thrombin activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor, histidine-rich glycoprotein, osteopontin, uteroglobin, and thrombospondin (12, 22).

TABLE 1.

Identified FXIIIa substrates and reactive Gln residues

Fractionated plasma was incubated with FXIIIa in the presences of BPA for 30, 60, and 180 min. Following tryptic digestion, BPA-labeled peptides were extracted and identified by LC-MS/MS. The identified substrates are listed according to the total number of spectral counts. The number of spectral counts was used to evaluate the level of BPA incorporation over time for a given protein. A change in the spectral count of more than 30% compared to the previous time point is indicated with U for up-regulated or D for down-regulated. No regulation is indicated by N if the change is less than 30%. The Sites column lists the total number of reactive Gln residue found in the substrate, and Clot ID indicates whether the substrate was found cross-linked to the plasma clot.

| Accession number | Name | Sites | Spectral counts |

Clot ID | Transdaba | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 min | 60 min | 180 min | ||||||

| 1 | P02671 | Fibrinogen α-chain | 8 | U | N | N | × | × |

| 2 | P01023 | α2-Macroglobulin | 15 | U | U | N | × | × |

| 3 | P00488 | Coagulation factor XIII A chain | 8 | U | U | N | × | |

| 4 | P00747 | Plasminogen | 20 | U | U | N | × | × |

| 5 | P00734 | Prothrombin | 11 | U | U | N | × | |

| 6 | P19823 | Inter-α-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H2 | 16 | U | U | N | × | × |

| 7 | P06727 | Apolipoprotein A-IV | 18 | U | U | U | × | |

| 8 | P01024 | Complement C3 | 27 | U | U | N | × | × |

| 9 | P02787 | Serotransferrin | 10 | U | U | U | × | |

| 10 | P0C0L5 | Complement C4-B | 19 | U | U | N | ||

| 11 | P19827 | Inter-α-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H1 | 11 | U | N | N | × | × |

| 12 | P10909 | Clusterin | 5 | U | U | U | × | |

| 13 | P02679 | Fibrinogen γ-chain | 5 | U | N | N | × | × |

| 14 | P08697 | α2-Antiplasmin | 11 | U | U | U | × | × |

| 15 | P07360 | Complement component C8 γ-chain | 7 | U | U | N | ||

| 16 | P07357 | Complement component C8 α-chain | 9 | U | U | N | ||

| 17 | P02751 | Fibronectin | 22 | U | U | N | × | × |

| 18 | P02649 | Apolipoprotein E | 13 | U | U | U | × | |

| 19 | P02652 | Apolipoprotein A-II | 4 | U | U | U | ||

| 20 | P07225 | Vitamin K-dependent protein S | 6 | U | U | N | ||

| 21 | P06396 | Gelsolin | 7 | U | U | N | × | |

| 22 | P04004 | Vitronectin | 6 | U | U | N | × | × |

| 23 | P02656 | Apolipoprotein C-III | 4 | U | U | N | ||

| 24 | Q16610 | Extracellular matrix protein 1 | 8 | U | U | U | × | |

| 25 | P01042 | Kininogen-1 | 11 | U | U | U | × | |

| 26 | P27169 | Serum paraoxonase/arylesterase 1 | 3 | U | N | N | ||

| 27 | P04003 | C4b-binding protein α-chain | 9 | U | U | U | × | |

| 28 | P03952 | Plasma kallikrein | 8 | U | U | U | ||

| 29 | Q08380 | Galectin-3-binding protein | 4 | U | U | N | ||

| 30 | P10643 | Complement component C7 | 13 | U | U | U | ||

| 31 | P01857 | Igγ-1 chain C regionb | 3 | U | U | N | × | |

| 32 | P23142 | Fibulin-1 | 8 | U | U | N | × | |

| 33 | P00742 | Coagulation factor X | 6 | U | U | U | ||

| 34 | Q14520 | Hyaluronan-binding protein 2 | 4 | U | U | N | ||

| 35 | Q13790 | Apolipoprotein F | 1 | U | U | N | ||

| 36 | P48740 | Mannan-binding lectin serine protease 1 | 3 | U | N | N | ||

| 37 | Q06033 | Inter-α-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H3 | 3 | U | U | N | ||

| 38 | P02760 | Protein AMBP | 3 | U | U | U | × | × |

| 39 | P02647 | Apolipoprotein A-I | 4 | U | U | U | × | × |

| 40 | P01880 | Ig δ-chain C region | 3 | U | U | U | ||

| 41 | P26927 | Hepatocyte growth factor-like protein | 8 | U | N | U | ||

| 42 | P12259 | Coagulation factor V | 7 | U | N | N | × | |

| 43 | P43652 | Afamin | 11 | U | U | U | ||

| 44 | Q9BUN1 | Protein MENT | 1 | U | U | N | ||

| 45 | Q14624 | Inter-α-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H4 | 5 | U | N | U | × | |

| 46 | P04275 | von Willebrand factor | 12 | U | U | N | × | × |

| 47 | P05156 | Complement factor I | 7 | U | U | U | ||

| 48 | P00740 | Coagulation factor IX | 3 | U | U | N | ||

| 49 | P02655 | Apolipoprotein C-II | 2 | U | U | U | ||

| 50 | P00748 | Coagulation factor XII | 5 | U | U | U | ||

| 51 | P01008 | Antithrombin-III | 6 | U | U | U | ||

| 52 | P02790 | Hemopexin | 4 | U | U | U | ||

| 53 | P62736 | Actin, aortic smooth muscle | 3 | U | U | N | × | |

| 54 | Q15582 | Transforming growth factor-β-induced protein ig-h3 | 1 | U | U | D | ||

| 55 | P80108 | Phosphatidylinositol-glycan-specific phospholipase D | 3 | U | N | U | ||

| 56 | P02765 | α2-HS-glycoprotein | 2 | U | U | U | × | |

| 57 | P49908 | Selenoprotein P | 2 | U | U | N | ||

| 58 | P01876 | Ig α-1 chain C regionb | 5 | U | U | U | × | |

| 59 | P01871 | Ig mu chain C region | 5 | U | U | U | × | |

| 60 | P22792 | Carboxypeptidase N subunit 2 | 4 | U | U | U | ||

| 61 | P08603 | Complement factor H | 12 | U | U | U | ||

| 62 | P04070 | Vitamin K-dependent protein C | 4 | U | U | N | ||

| 63 | P05546 | Heparin cofactor 2 | 5 | U | U | U | ||

| 64 | P02748 | Complement component C9 | 3 | U | U | N | ||

| 65 | Q14515 | SPARC-like protein 1 | 3 | U | U | N | ||

| 66 | P49747 | Cartilage oligomeric matrix protein | 3 | U | U | N | ||

| 67 | P69905 | Hemoglobin subunit α | 1 | U | U | U | × | |

| 68 | P40967 | Melanocyte protein PMEL | 1 | U | ||||

| 69 | P00751 | Complement factor B | 8 | U | U | U | ||

| 70 | P35858 | Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein complex acid labile subunit | 3 | U | U | U | × | |

| 71 | P01834 | Ig κ-chain C region | 2 | U | U | U | × | |

| 72 | P22891 | Vitamin K-dependent protein Z | 4 | U | U | U | ||

| 73 | P02675 | Fibrinogen β-chain | 6 | U | U | U | × | |

| 74 | P02749 | β2-Glycoprotein 1 | 1 | U | U | U | ||

| 75 | P35579 | Myosin-9 | 1 | U | N | × | ||

| 76 | Q07954 | Prolow-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 | 1 | U | U | |||

| 77 | P07358 | Complement component C8 β-chain | 6 | U | U | U | ||

| 78 | Q04756 | Hepatocyte growth factor activator | 2 | U | U | U | ||

| 79 | Q9Y490 | Talin-1 | 4 | U | U | D | × | |

| 80 | P00746 | Complement factor D | 2 | U | U | |||

| 81 | P0C0L4 | Complement C4-A | 21 | U | N | × | ||

| 82 | P05155 | Plasma protease C1 inhibitor | 5 | U | U | |||

| 83 | P01031 | Complement C5 | 8 | U | U | × | ||

| 84 | P02768 | Serum albumin | 8 | U | U | × | ||

| 85 | O75882 | Attractin | 1 | U | N | |||

| 86 | P13671 | Complement component C6 | 7 | U | U | |||

| 87 | P20851 | C4b-binding protein β-chain | 4 | U | U | |||

| 88 | O14791 | Apolipoprotein L1 | 2 | U | U | |||

| 89 | P00736 | Complement C1r subcomponent | 9 | U | U | |||

| 90 | Q6EMK4 | Vasorin | 2 | U | U | |||

| 91 | O95445 | Apolipoprotein M | 2 | U | U | |||

| 92 | P27918 | Properdin | 2 | U | N | |||

| 93 | Q12805 | EGF-containing fibulin-like extracellular matrix protein 1 | 3 | U | N | × | ||

| 94 | P00739 | Haptoglobin-related protein | 1 | U | N | × | ||

| 95 | P24592 | Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 6 | 2 | U | D | |||

| 96 | P02774 | Vitamin D-binding protein | 6 | U | U | |||

| 97 | O43866 | CD5 antigen-like | 1 | U | U | × | ||

| 98 | Q04721 | Neurogenic locus notch homolog protein 2 | 1 | U | ||||

| 99 | P00450 | Ceruloplasmin | 4 | U | U | × | ||

| 100 | P09871 | Complement C1s subcomponent | 4 | U | U | × | ||

| 101 | P04406 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 1 | U | N | × | ||

| 102 | P08571 | Monocyte differentiation antigen CD14 | 1 | U | U | |||

| 103 | Q6UXB8 | Peptidase inhibitor 16 | 2 | U | U | |||

| 104 | Q9Y240 | C-type lectin domain family 11 member A | 1 | U | ||||

| 105 | Q9UJU6 | Drebrin-like protein | 1 | U | ||||

| 106 | Q9UJJ9 | N-Acetylglucosamine-1-phosphotransferase subunit γ | 1 | U | ||||

| 107 | Q9ULI3 | Protein HEG homolog 1 | 1 | U | ||||

| 108 | Q9UGM5 | Fetuin-B | 3 | U | U | × | ||

| 109 | P68871 | Hemoglobin subunit β | 1 | U | U | × | ||

| 110 | P05452 | Tetranectin | 3 | U | U | |||

| 111 | P31946 | 14-3-3 protein β/α | 2 | U | U | |||

| 112 | Q15942 | Zyxin | 2 | U | N | |||

| 113 | Q9Y6R7 | IgGFc-binding protein | 5 | U | U | |||

| 114 | P06681 | Complement C2 | 1 | U | U | |||

| 115 | P51884 | Lumican | 2 | U | U | |||

| 116 | Q96EE4 | Coiled-coil domain-containing protein 126 | 1 | U | U | |||

| 117 | Q9BWP8 | Collectin-11 | 2 | U | N | |||

| 118 | P04264 | Keratin, type II cytoskeletal 1 | 1 | U | ||||

| 119 | P01877 | Ig α-2 chain C regionb | 5 | U | ||||

| 120 | P04217 | α-1B-Glycoprotein | 4 | U | ||||

| 121 | P0CG04 | Ig λ-1 chain C regions | 1 | U | × | |||

| 122 | P00738 | Haptoglobin | 3 | U | ||||

| 123 | P15169 | Carboxypeptidase N catalytic chain | 3 | U | ||||

| 124 | P02654 | Apolipoprotein C-I | 1 | U | ||||

| 125 | P01766 | Ig heavy chain V-III region BRO/TILb | 1 | U | × | |||

| 126 | O75636 | Ficolin-3 | 1 | U | ||||

| 127 | Q96PD5 | N-Acetylmuramoyl-l-alanine amidase | 2 | U | ||||

| 128 | P03951 | Coagulation factor XI | 1 | U | ||||

| 129 | P13598 | Intercellular adhesion molecule 2 | 1 | U | ||||

| 130 | P08519 | Apolipoprotein(a) | 1 | U | ||||

| 131 | P05160 | Coagulation factor XIII B chain | 1 | U | ||||

| 132 | Q9NZP8 | Complement C1r subcomponent-like protein | 1 | U | ||||

| 133 | P11142 | Heat shock cognate 71-kDa protein | 1 | U | ||||

| 134 | P04278 | Sex hormone-binding globulin | 1 | U | ||||

| 135 | P62328 | Thymosin β-4 | 1 | U | ||||

| 136 | Q9UBG0 | C-type mannose receptor 2 | 1 | U | ||||

| 137 | P34931 | Heat shock 70-kDa protein 1-like | 1 | U | ||||

| 138 | P01620 | Ig κ-chain V-III region SIE | 1 | U | ||||

| 139 | Q92954 | Proteoglycan 4 | 1 | U | ||||

| 140 | Q76LX8 | A disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs 13 | 1 | U | ||||

| 141 | P05090 | Apolipoprotein D | 1 | U | ||||

| 142 | Q99490 | Arf-GAP with GTPase, ANK repeat, and PH domain-containing protein 2 | 1 | U | ||||

| 143 | Q9H4A9 | Dipeptidase 2 | 1 | U | ||||

| 144 | P14314 | Glucosidase 2 subunit β | 1 | U | ||||

| 145 | Q14697 | Neutral α-glucosidase AB | 1 | U | ||||

| 146 | P55058 | Phospholipid transfer protein | 1 | U | ||||

| 147 | P07359 | Platelet glycoprotein Ibα chain | 1 | U | ||||

a Updated Transdab information (3, 25). Detailed information can be found in supplemental Table S1.

b Sequence redundancy prevents identification of a unique protein or reactive Gln residue; identified proteins are grouped as one substrate identification using a representative protein name.

To look at the time dependence of the reaction, we used three different incubation times including 30, 60, and 180 min. It was evident that additional BPA-labeled proteins were identified as the incubation time was increased, with 80 proteins being identified at 30 min, 115 proteins being identified at 60 min, and 139 proteins being identified at 180 min. The total number of MS spectra identifying the labeled peptides of a given protein was used to estimate the level of BPA incorporation over time (Table 1 and supplemental Table S1). Labeling of the α- and γ-fibrin chains was completed after 30 min with no increase in the number of spectra over time. For most other proteins, the total spectral count increases over time.

The contribution of endogenous transglutaminase was determined by preparing control samples without the addition of FXIIIa (supplemental Table S1). In these samples, we only identified α2-antiplasmin, α2-macroglobulin, fibrinogen α-chain, and fibrinogen γ-chain as substrates. We cannot differentiate between the activities of the endogenous transglutaminases (e.g., transglutaminase 2 and FXIII). However, all four proteins are known FXIIIa substrates, and because transglutaminase 2 is not identified in the human plasma proteome, we ascribe the endogenous activity to FXIIIa (23).

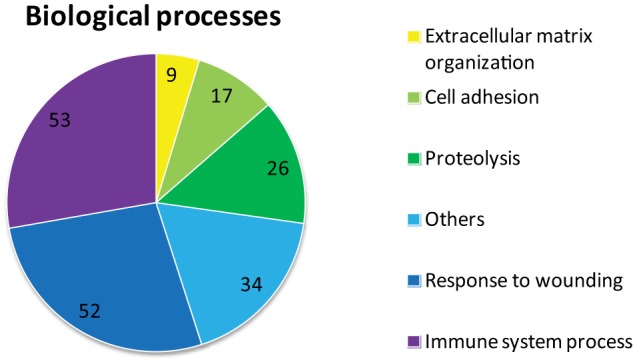

The identified proteins were annotated with Gene Ontology information from the Uniprot database using MS Data Miner (21). Six general Gene Ontology summary categories were defined and used to group the substrates (Fig. 1). Most of the proteins were linked to biological processes involved in wound healing, immune system processes, proteolysis, cell adhesion, and extracellular matrix organization. The subcategories, which are heavily represented among the substrates, are coagulation, complement activation, inflammatory response, and platelet activation (supplemental Table S1).

FIGURE 1.

Gene Ontology summary of the identified FXIIIa substrates. The Gene Ontology annotations of the identified FXIIIa substrates are summarized by six categories with the number of proteins in each category in a pie chart. Seven unannotated proteins are not represented. The Others category include 15 proteins annotated to transport processes. These proteins are, among others, apolipoproteins, hemoglobin, ceruloplasmin, and vitamin D-binding protein. A large group of substrates are annotated to the Response to wounding and Immune system process categories. The Response to wounding category is mainly comprised of proteins annotated to coagulation and to the inflammatory response. In the Immune system processes category, proteins annotated to complement activation are heavily represented. The data suggest that FXIIIa-mediated cross-linking plays a role beyond clot stabilization during coagulation.

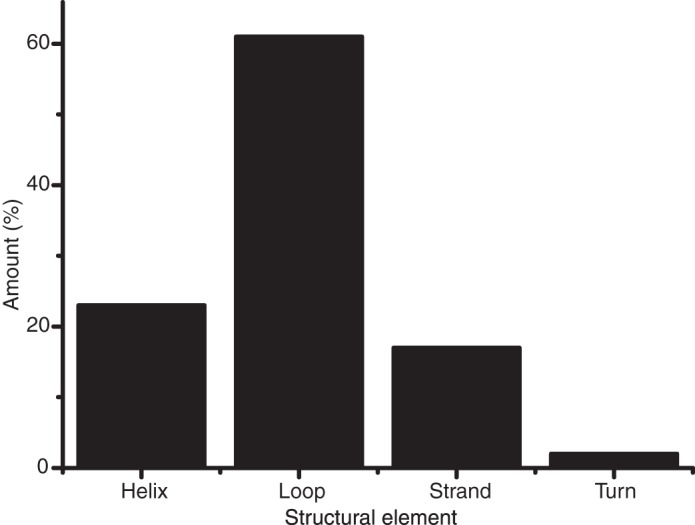

The identified reactive sites (690 in total) were utilized in a search for a consensus sequence. Aligning 20 residues on either site of the reactive Gln residues did not reveal a clear consensus. However, there was a small increase in the frequency of acidic residues (Glu and Asp) in positions 1 and 2, N-terminal to the reactive Gln residues. In addition, the frequency of basic residues (Arg, Lys, and His) was increased in positions 4–12, particularly in positions 9 and 10 (supplemental Table S1). Moreover, Pro was never observed in the first position C-terminal to the reactive Gln residues (supplemental Table S1). We furthermore analyzed whether any structural elements were overrepresented by the reactive Gln residues. Secondary structural information was available in the Uniprot database for 481 of the 690 reactive Gln residues, and for each of these sites, the reactive residue was assigned as a helix, strand, turn, or loop (Fig. 2). Clear overrepresentation of reactive Gln in loops was seen, with 61% of the sites being found in loop regions.

FIGURE 2.

Secondary structure localization of reactive Gln residues. Secondary structural information was extracted from the UniProt database for 389 of the 549 reactive Gln residues. The reactive residues could therefore be assigned to helix, strand, turn, or loop. The data suggest that reactive Gln residues are overrepresented in loops.

Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis of the Clot Proteome

The major physiological function of FXIIIa is to stabilize the plasma clot by cross-linking polymerized fibrin. In addition to fibrin cross-linking, FXIIIa also cross-links other plasma proteins to the clot. To determine whether FXIIIa incorporates the identified substrates into the clot, we isolated covalently associated clot proteins from an extensively washed plasma clot using SDS-PAGE. The use of SDS-PAGE enabled us to separate the insoluble clot proteins from SDS-soluble proteins that are associated noncovalently to the clot. The covalently bound proteins were collected on the top of the stacking gel. The isolated clot material was digested with trypsin and either prefractionated using strong cation exchange chromatography or analyzed directly by LC-MS/MS.

Using the strong cation exchange-fractionated material, we were able to identify 70 proteins (supplemental Table S2). These are likely to represent proteins that are covalently cross-linked to the clot. Such cross-linking can be mediated either by FXIIIa directly or indirectly (e.g., protease inhibitor complex) or by an unrelated cross-linking reaction. Of the 70 identified proteins, 48 were identified in this study as FXIIIa substrates (Table 1). Furthermore, we identified 14 of the 20 known plasma FXIIIa substrates in the clot.

The level of noncovalently bound proteins remaining in the clot following the extensive washing and SDS-PAGE procedures was investigated. This was done by incubating a plasma clot and isotope-labeled proteins produced by liver cells in the presence of an FXIIIa inhibitor. The medium contained 45 of the 70 proteins identified in the clot. After the extensive washing and SDS-PAGE, the sample was analyzed by LC-MS/MS. The analysis did not reveal the presence of isotope-labeled proteins, suggesting that noncovalently bound proteins were removed by the described procedure (data not shown).

To estimate the relative amount of the proteins present in the isolated clot material, we performed a label-free relative quantification based on extracted ion chromatography. In short, the relative abundance of proteins was based on the average intensity for the three most intense peptides from a minimum of three MS runs. Of the identified clot proteins, only data for 14 proteins met the requirements for quantification (Table 2). As expected, fibrin constitutes the major protein component of the plasma clot, representing more than 90% of the total protein amount. The quantified proteins are all identified as FXIIIa substrates either in this study or in the case of histidine-rich glycoprotein in a previous study (24).

TABLE 2.

Quantification of plasma clot proteins

A plasma clot was extensively washed and subjected to SDS-PAGE. The clot material that did not migrate into the gel was digested with trypsin and analyzed by LC-MS/MS. The relative abundance of identified proteins was calculated using extracted ion chromatography. The calculation was based on the average intensity for the three most intense peptides from each protein. The relative amounts (%) and standard deviations are based on a minimum of three MS runs. The 14 quantified proteins are all FXIIIa substrates.

| Accession number | Name | Extracted ion chromatography quantitation |

|---|---|---|

| % | ||

| P02671 | Fibrinogen α-chain | 40.0 ± 2.3 |

| P02675 | Fibrinogen β-chain | 30.7 ± 4.0 |

| P02679 | Fibrinogen γ-chain | 19.8 ± 2.9 |

| P02751 | Fibronectin | 4.9 ± 1.0 |

| P08697 | α2-Antiplasmin | 1.6 ± 0.2 |

| P02768 | Serum albumin | 0.6 ± 0.1 |

| P04196 | Histidine-rich glycoprotein | 0.5 ± 0.1 |

| P01857 | Igγ-1 chain C region | 0.5 ± 0.1 |

| Q16610 | Extracellular matrix protein 1 | 0.4 ± 0.0 |

| P01023 | α2-Macroglobulin | 0.2 ± 0.1 |

| P00747 | Plasminogen | 0.2 ± 0.0 |

| P01860 | Igγ-3 chain C region | 0.2 ± 0.0 |

| P00488 | Coagulation factor XIII A chain | 0.1 ± 0.0 |

| P01024 | Complement C3 | 0.1 ± 0.0 |

DISCUSSION

The transglutaminases are generally thought to display high substrate specificity. Although the same protein substrate is often recognized by several transglutaminases, the reactivity and specificity differ among the isoenzymes (25). The majority of the specificity is directed toward the reactive Gln residue and for transglutaminase 2 (also called tissue transglutaminase), this residue is often found in a flexible region of the protein (26). Previous attempts to identify a sequence explaining the specificity of FXIIIa have not resulted in a clear consensus (27, 28). We were able to identify 690 unique FXIIIa substrate sequences. This represents to our knowledge the most comprehensive list of substrate sequences. The alignment of these identified sequences still does not reveal a consensus sequence, making it unlikely that the primary structure surrounding the reactive Gln alone is responsible for substrate recognition. An examination of secondary structure revealed that the reactive Gln residues are present at a higher frequency in loops, which has also been observed in a previous study on transglutaminase 2 substrates (26). The structural information from the 690 substrate sites shows that substrate recognition is mainly based on a structural recognition and that the primary sequence only has a minor role.

The experimental setup also included analyses where fixed concentrations of FXIIIa, BPA, and plasma were incubated for an increasing amount of time. The results did not reveal a definite number of FXIIIa substrates, but rather that additional proteins were labeled as the reaction was allowed to continue. The reason for this observation could be that as high affinity substrates become saturated with BPA, the FXIIIa activity is directed toward other substrates. It is possible that inactivation of FXIIIa (29) and substrate competition during coagulation in vivo will preferably cause only the high affinity substrates to be cross-linked by FXIIIa.

In addition to its role in coagulation, FXIIIa also plays a role in wound healing, although this is less well described. It is likely that substrates other than the high affinity substrates might become relevant during wound healing or during pathological situations with prolonged FXIIIa activity. Prolonged FXIIIa activity has been demonstrated in relation to tissue regeneration in mice healing from myocardial infarction and in relation to ischemia following thromboembolic stroke (30, 31).

To investigate which of the identified proteins are relevant FXIIIa substrates during coagulation, we identified proteins that are covalently associated with the plasma clot. Of the 70 proteins that were identified in the plasma clot, 48 were also identified as FXIIIa substrates. We did not investigate whether the 48 substrates are cross-linked to fibrin directly. However, it is known that fibrin contains several reactive Lys residues, and fibrin could therefore serve as a nucleus for the attachment of other proteins (2).

The relevance of the 99 substrates that were not identified in the plasma clot can rightly be questioned. These substrates do not seem to be cross-linked to the plasma clot during coagulation. However, FXIIIa is known to be involved in several other biological processes including wound healing, maintaining pregnancy, extracellular matrix formation, and angiogenesis (32). It is very likely that only a fraction of the 147 identified FXIIIa substrates is directly involved in coagulation, whereas the remaining proteins are relevant substrates during other biological processes.

The observation that the 14 most abundant proteins in the cross-linked plasma clot are FXIIIa substrates supports the concept of an FXIIIa-mediated functionalization of the plasma clot. The significance of this can be exemplified by the cross-linking of α2-antiplasmin to the clot and the subsequent reduction of plasmin-mediated fibrinolysis (33). In a similar manner, the identified FXIIIa substrates could all functionalize the clot and alter clot characteristics. Traditionally focus has been on FXIIIa-mediated stabilization of the clot, but our results suggest that FXIIIa may affect other characteristics of both the clot and the provisional matrix. Several of the identified substrates have functions in neutralizing enzymes and regulating proteolysis; in opsonization and trapping of micro-organisms; in activating complement and modulating the host defense response; in scavenging free hemoglobin, iron, and radicals; and in angiogenesis.

It is becoming increasingly clear that the activation of the coagulation and complement systems is synchronized during several physiological and pathological processes (34). Our present study supports the evidence of cross-talk between the two systems. We show that almost the entire complement system is a target for FXIIIa. The main function of the complement system is to create a pro-inflammatory environment with phagocytosis and lysis of pathogens and damaged cells, removal of immune complexes, and activation and migration of inflammatory cells (35). During wound healing, activity of both coagulation and complement is needed to maintain tissue integrity and prevent infection. A recent study showed that FXIIIa itself is able to protect against bacterial infection by cross-linking bacteria at the site of FXIIIa activation (36). This immobilization of bacteria was paralleled by an antimicrobial activity that might involve the complement system. It is possible that FXIIIa-immobilized complement complexes mediate the bacterial cross-linking to fibrin. Such a system could trap all bacteria recognized by the complement system independent of pathogen originating FXIIIa substrates. Curiously, coagulation results in the FXIIIa-dependent generation of a protein with antigenicity and chemotatic activity similar to C5a (37). We have identified reactive Gln residues in the C5a sequence, implying that the chemotactic agent could result from the cross-linking of C5a to another plasma protein during coagulation. We identified several immunoglobulins, including IgG and IgM, as FXIIIa substrates. These immunoglobulins are in antibody-antigen complexes able to activate complement and may also, by binding bacterial surfaces, directly promote phagocytosis of the bacteria. It seems plausible that FXIIIa is able to regulate the defense response during wound healing to promote bacterial clearance and immune cell migration through the interaction with these substrates.

In this study, we have also identified several structural proteins such as vitronectin, fibronectin, lumican, fibulin-1, and extracellular matrix protein 1 as FXIIIa substrates. Structural integrity and stability of the clot is essential to hinder bleedings and dislodging of the clot from the site of coagulation. Cross-linking of structural proteins to the fibrin clot can significantly influence the formation and stability of the clot as seen with fibronectin (38, 39). Cross-linking of fibronectin and fibrin by FXIIIa increases both thrombus size and platelet adherence (38). Many structural proteins interact with cell surface receptors and are through these interactions able to affect cell adhesion, migration, and proliferation. FXIIIa could alter cell matrix signaling by inducing structural changes in substrates or by remodeling the extracellular matrix. This has been illustrated by cell adhesion and migration experiments performed with mutated variants of fibronectin that cannot be cross-linked to fibrin by FXIIIa. The experiment clearly showed that the presence of fibronectin alone was not enough to ensure maximal cell adhesion; cross-linking is needed (15). We hypothesize that several of the identified FXIIIa substrates may, similarly to fibronectin, alter the function and stability of the clot upon cross-linking. One potential candidate is extracellular matrix protein 1. We found this previously unknown FXIIIa substrate in the clot in similar amounts as α2-macroglobulin (Table 2). Extracellular matrix protein 1 is a known promotor of angiogenesis that interacts with several extracellular matrix components including fibronectin, laminin, and hyaluronan (40, 41). Cross-linking of extracellular matrix protein 1 to the plasma clot could both influence angiogenesis and increase the anchoring of the clot to the extracellular matrix.

In summary, this study identifies 147 FXIIIa substrates and shows that FXIIIa is able to cross-link a minimum of 48 proteins to the plasma clot. These results indicate that FXIIIa is involved in an extensive functionalization of the plasma clot that could influence different processes such as complement activation, coagulation, inflammatory and immune responses, and extracellular matrix organization.

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplemental spectra and Tables S1 and S2.

- FXIII

- coagulation factor XIII

- FXIIIa

- activated coagulation factor XIII

- TG

- transglutaminase

- BPA

- 5-(biotinamido)pentylamine.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lippi G., Franchini M., Targher G. (2011) Arterial thrombus formation in cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 8, 502–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lorand L. (2001) Factor XIII. Structure, activation, and interactions with fibrinogen and fibrin. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 936, 291–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Muszbek L., Bereczky Z., Bagoly Z., Komáromi I., Katona E. (2011) Factor XIII. A coagulation factor with multiple plasmatic and cellular functions. Physiol. Rev. 91, 931–972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rittirsch D., Flierl M. A., Ward P. A. (2008) Harmful molecular mechanisms in sepsis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8, 776–787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lorand L., Graham R. M. (2003) Transglutaminases. Crosslinking enzymes with pleiotropic functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4, 140–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lorand L. (2005) Factor XIII and the clotting of fibrinogen. From basic research to medicine. J. Thromb. Haemost. 3, 1337–1348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hsieh L., Nugent D. (2008) Factor XIII deficiency. Haemophilia 14, 1190–1200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sakata Y., Aoki N. (1982) Significance of cross-linking of α2-plasmin inhibitor to fibrin in inhibition of fibrinolysis and in hemostasis. J. Clin. Invest. 69, 536–542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Francis R. T., McDonagh J., Mann K. G. (1986) Factor V is a substrate for the transamidase factor XIIIa. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 9787–9792 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Valnickova Z., Enghild J. J. (1998) Human procarboxypeptidase U, or thrombin-activable fibrinolysis inhibitor, is a substrate for transglutaminases. Evidence for transglutaminase-catalyzed cross-linking to fibrin. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 27220–27224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hada M., Kaminski M., Bockenstedt P., McDonagh J. (1986) Covalent crosslinking of von Willebrand factor to fibrin. Blood 68, 95–101 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nikolajsen C. L., Scavenius C., Enghild J. J. (2012) Human complement C3 is a substrate for transglutaminases. A functional link between non-protease-based members of the coagulation and complement cascades. Biochemistry 51, 4735–4742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Scavenius C., Sanggaard K. W., Nikolajsen C. L., Bak S., Valnickova Z., Thøgersen I. B., Jensen O. N., Højrup P., Enghild J. J. (2011) Human inter-α-inhibitor is a substrate for factor XIIIa and tissue transglutaminase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1814, 1624–1630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ritchie H., Robbie L. A., Kinghorn S., Exley R., Booth N. A. (1999) Monocyte plasminogen activator inhibitor 2 (PAI-2) inhibits u-PA-mediated fibrin clot lysis and is cross-linked to fibrin. Thromb. Haemost. 81, 96–103 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Corbett S. A., Lee L., Wilson C. L., Schwarzbauer J. E. (1997) Covalent cross-linking of fibronectin to fibrin is required for maximal cell adhesion to a fibronectin-fibrin matrix. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 24999–25005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Richardson V. R., Cordell P., Standeven K. F., Carter A. M. (2013) Substrates of Factor XIII-A. Roles in thrombosis and wound healing. Clin. Sci. 124, 123–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ruoppolo M., Orrù S., D'Amato A., Francese S., Rovero P., Marino G., Esposito C. (2003) Analysis of transglutaminase protein substrates by functional proteomics. Protein Sci. 12, 1290–1297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dørum S., Arntzen M. O., Qiao S. W., Holm A., Koehler C. J., Thiede B., Sollid L. M., Fleckenstein B. (2010) The preferred substrates for transglutaminase 2 in a complex wheat gluten digest are Peptide fragments harboring celiac disease T-cell epitopes. PLoS One 5, e14056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kronvall G., Simmons A., Myhre E. B., Jonsson S. (1979) Specific absorption of human serum albumin, immunoglobulin A, and immunoglobulin G with selected strains of group A and G streptococci. Infect. Immun. 25, 1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kussmann M., Nordhoff E., Rahbek-Nielsen H., Haebel S., Rossel-Larsen M., Jakobsen L., Gobom J., Mirgorodskaya E., Kroll-Kristensen A., Palm L., Roepstorff P. (1997) Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry sample preparation techniques designed for various peptide and protein analytes. J. Mass Spectrom. 32, 593–601 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dyrlund T. F., Poulsen E. T., Scavenius C., Sanggaard K. W., Enghild J. J. (2012) MS Data Miner. A web-based software tool to analyze, compare, and share mass spectrometry protein identifications. Proteomics 12, 2792–2796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Csosz E., Meskó B., Fésüs L. (2009) Transdab wiki. The interactive transglutaminase substrate database on web 2.0 surface. Amino Acids 36, 615–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Omenn G. S., States D. J., Adamski M., Blackwell T. W., Menon R., Hermjakob H., Apweiler R., Haab B. B., Simpson R. J., Eddes J. S., Kapp E. A., Moritz R. L., Chan D. W., Rai A. J., Admon A., Aebersold R., Eng J., Hancock W. S., Hefta S. A., Meyer H., Paik Y. K., Yoo J. S., Ping P., Pounds J., Adkins J., Qian X., Wang R., Wasinger V., Wu C. Y., Zhao X., Zeng R., Archakov A., Tsugita A., Beer I., Pandey A., Pisano M., Andrews P., Tammen H., Speicher D. W., Hanash S. M. (2005) Overview of the HUPO Plasma Proteome Project. Results from the pilot phase with 35 collaborating laboratories and multiple analytical groups, generating a core dataset of 3020 proteins and a publicly-available database. Proteomics 5, 3226–3245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Halkier T., Andersen H., Vestergaard A., Magnusson S. (1994) Bovine histidine-rich glycoprotein is a substrate for bovine plasma factor XIIIa. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 200, 78–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gorman J. J., Folk J. E. (1984) Structural features of glutamine substrates for transglutaminases. Role of extended interactions in the specificity of human plasma factor XIIIa and of the guinea pig liver enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 259, 9007–9010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Csosz E., Bagossi P., Nagy Z., Dosztanyi Z., Simon I., Fesus L. (2008) Substrate preference of transglutaminase 2 revealed by logistic regression analysis and intrinsic disorder examination. J. Mol. Biol. 383, 390–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sugimura Y., Hosono M., Wada F., Yoshimura T., Maki M., Hitomi K. (2006) Screening for the preferred substrate sequence of transglutaminase using a phage-displayed peptide library. Identification of peptide substrates for TGASE 2 and factor XIIIA. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 17699–17706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Coussons P. J., Price N. C., Kelly S. M., Smith B., Sawyer L. (1992) Factors that govern the specificity of transglutaminase-catalysed modification of proteins and peptides. Biochem. J. 282, 929–930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Robinson B. R., Houng A. K., Reed G. L. (2000) Catalytic life of activated factor XIII in thrombi. Implications for fibrinolytic resistance and thrombus aging. Circulation 102, 1151–1157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhang Y., Fan S., Yao Y., Ding J., Wang Y., Zhao Z., Liao L., Li P., Zang F., Teng G. J. (2012) In vivo near-infrared imaging of fibrin deposition in thromboembolic stroke in mice. PLoS One 7, e30262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nahrendorf M., Aikawa E., Figueiredo J. L., Stangenberg L., van den Borne S. W., Blankesteijn W. M., Sosnovik D. E., Jaffer F. A., Tung C. H., Weissleder R. (2008) Transglutaminase activity in acute infarcts predicts healing outcome and left ventricular remodelling. Implications for FXIII therapy and antithrombin use in myocardial infarction. Eur. Heart J. 29, 445–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schroeder V., Kohler H. P. (2013) New developments in the area of factor XIII. J. Thromb. Haemost. 11, 234–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fraser S. R., Booth N. A., Mutch N. J. (2011) The antifibrinolytic function of factor XIII is exclusively expressed through α2-antiplasmin cross-linking. Blood 117, 6371–6374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Markiewski M. M., Nilsson B., Ekdahl K. N., Mollnes T. E., Lambris J. D. (2007) Complement and coagulation. Strangers or partners in crime? Trends Immunol. 28, 184–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ricklin D., Hajishengallis G., Yang K., Lambris J. D. (2010) Complement. A key system for immune surveillance and homeostasis. Nat. Immunol. 11, 785–797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Loof T. G., Mörgelin M., Johansson L., Oehmcke S., Olin A. I., Dickneite G., Norrby-Teglund A., Theopold U., Herwald H. (2011) Coagulation, an ancestral serine protease cascade, exerts a novel function in early immune defense. Blood 118, 2589–2598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Okamoto M., Yamamoto T., Matsubara S., Kukita I., Takeya M., Miyauchi Y., Kambara T. (1992) Factor XIII-dependent generation of 5th complement component (C5)-derived monocyte chemotactic factor coinciding with plasma clotting. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1138, 53–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cho J., Mosher D. F. (2006) Enhancement of thrombogenesis by plasma fibronectin cross-linked to fibrin and assembled in platelet thrombi. Blood 107, 3555–3563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ni H., Yuen P. S., Papalia J. M., Trevithick J. E., Sakai T., Fässler R., Hynes R. O., Wagner D. D. (2003) Plasma fibronectin promotes thrombus growth and stability in injured arterioles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 2415–2419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Han Z., Ni J., Smits P., Underhill C. B., Xie B., Chen Y., Liu N., Tylzanowski P., Parmelee D., Feng P., Ding I., Gao F., Gentz R., Huylebroeck D., Merregaert J., Zhang L. (2001) Extracellular matrix protein 1 (ECM1) has angiogenic properties and is expressed by breast tumor cells. FASEB J. 15, 988–994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sercu S., Zhang M., Oyama N., Hansen U., Ghalbzouri A. E., Jun G., Geentjens K., Zhang L., Merregaert J. H. (2008) Interaction of extracellular matrix protein 1 with extracellular matrix components. ECM1 is a basement membrane protein of the skin. J. Invest. Dermatol. 128, 1397–1408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.