In the United States, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), viral hepatitis, sexually transmitted disease (STD), and tuberculosis (TB) infections are among the most prevalent and most commonly reported conditions—with STDs alone accounting for more than 19 million new infections per year and direct costs in excess of $15 billion.1,2 Their nonrandom distribution in the population is characterized by increasing disease concentration among the poor, those with poor access to curative services, populations with a high prevalence of risky or stigmatized behaviors, or the socially marginalized. Strong vertical programs that provide highly specialized technical approaches to disease control have been the mainstay of the domestic efforts during the past four decades, with a focus on scaling up screening, diagnosis, treatment, and partner notification efforts. However, our evolved understanding of the complex and overlapping (syndemic) nature of these conditions and their close interrelationship with social and structural determinants has necessitated the adoption of new approaches to enhance traditional disease control efforts.

Scientific evidence shows that genetic predisposition and risk behaviors only partially explain why some people become sick and others do not.3 Many chronic and infectious diseases cluster in populations that experience social and economic constraints to good health.4,5 These constraints, often referred to as social determinants of health (SDH), are the economic and social conditions that influence the health of individuals and communities.5 They determine the extent to which a person possesses the physical, social, and personal resources to identify and achieve personal goals, satisfy needs, cope with the environment, and achieve optimal health.

In 2008, the World Health Organization (WHO) published the final report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health, entitled “Closing the Gap in a Generation—Health Equity through Action on the Social Determinants of Health.” In this report, the Commission issued a call for the “World Health Organization and all governments to lead global action on the social determinants of health with the aim of achieving health equity” and “closing the gap in a generation.”5 Since the publication of the Commission's report, there has been considerable movement by health agencies and governments to incorporate SDH as an approach to addressing health disparities and promoting health equity.6 A number of published studies address the value of integrating SDH into public health practice and the need to address data gaps by making use of a wide variety of data, including data on social determinants, to provide a more complete description of factors that may influence health outcomes.4–10

In 2008, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC's) National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention (NCHHSTP) held a consultation with more than 100 academic, scientific, and public health experts and community leaders to discuss effective ways to address the SDH of HIV, hepatitis, STDs, and TB. The goal was to identify future priorities and best practices for addressing societal factors that increase risk for these diseases and to inform CDC's efforts in accelerating the reduction of health inequities and the promotion of health equity.11 Consultants recommended CDC work to address SDH in four areas:

Public health policy: Provide leadership throughout CDC and align efforts with those of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and WHO.

Data systems: Create relevant metrics for SDH; add SDH to data-collection systems; and share, link, and integrate data to the extent possible to facilitate analyses and provide an evidence base, including identifying and using datasets and systems from other agencies.

Agency partnerships and capacity building: Enhance partnerships through traditional and nontraditional sources to strengthen the SDH effort, and build capacity among partners in SDH by including language in funding opportunity announcements (FOAs).

Prevention research and evaluation: Integrate a holistic and interdisciplinary approach to conducting prevention research.11

Consultant input was the basis from which NCHHSTP moved forward to implement key goals, assess accountability, and evaluate progress in responding to the consultation recommendations and achieving SDH goals and objectives over time. A complete summary of the consultation and additional information on recommendations appear elsewhere.11

Informed by recommendations of the external consultation, NCHHSTP has, for the past five years, systematically incorporated addressing SDH within its six-year strategic plan and public health work.12 This article describes progress made by NCHHSTP during the past five years in integrating an SDH approach using the four areas listed previously and a fifth area—health communication.

PROGRESS MADE IN ACHIEVING RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE 2008 CDC SDH CONSULTATION

Public health policy

Implementing structural change at the organizational level is important to ensure longstanding policy and programmatic changes. NCHHSTP developed a strategic plan focused on six overarching goals: (1) prevention through health care, (2) program collaboration and service integration, (3) health equity, (4) global health protection and systems strengthening, (5) partnerships and workforce development, and (6) capacity building to guide programmatic and policy decisions.12 The health equity goal has three objectives: (1) define and pursue a science-based approach to identify and eliminate health disparities related to HIV/AIDS, viral hepatitis, STDs, TB, and associated diseases and conditions; (2) mobilize partners and stakeholders to promote health equity and SDH as they relate to HIV, viral hepatitis, STD, and TB prevention; and (3) identify which SDH are important to address to reduce health disparities in HIV/AIDS, viral hepatitis, STDs, and TB, and develop and appropriate plans for addressing these social determinants in NCHHSTP programmatic, policy, and scientific work. NCHHSTP routinely assesses progress in these three areas with the intent of developing a more balanced programmatic and scientific portfolio that advances the goals of improving the health of communities and increasing their opportunities for healthy living.13 The tenets of the health equity goal are included in strategic plans of subordinate organizational units.14,15

CDC developed a white paper on SDH in 2010.16 This document provides an official set of proposals used for policy development to address health disparities incorporating an SDH framework. It includes commitments for CDC and partners in advancing health equity and social determinants in six critical public health areas: (1) research and surveillance, (2) health communication and marketing, (3) health policy, (4) prevention programs, (5) building capacity in science—in programs and with partners, and (6) enhancing partnerships.17 NCHHSTP routinely assesses progress in these six areas with the intent of developing a more balanced programmatic and scientific portfolio that advances the goals of improving the health of communities and increasing their opportunities for healthy living.13

To further enshrine the Center's commitment to integrating health equity and SDH approaches in all funded programmatic activities, NCHHSTP also developed specific definitions and requirements to be included in NCHHSTP FOAs. These requirements ensure that every NCHHSTP-funded FOA seeks to address health equity and SDH. By 2012, 20 NCHHSTP FOAs contained health equity and SDH definitions, rationale, and explicit encouragement for this approach to be incorporated into program planning and reporting by grantees.

Leadership and accountability

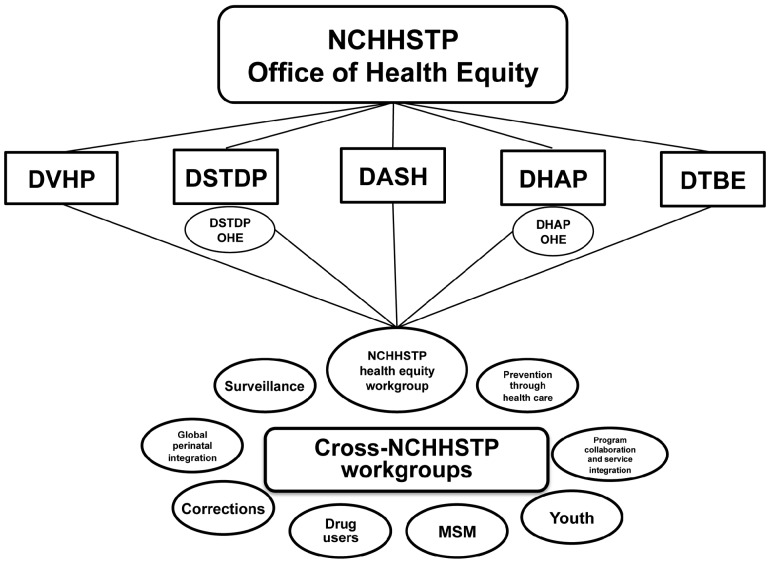

Robust strategic frameworks for health equity and SDH are necessary but insufficient to drive lasting change. Appropriate organizational infrastructure, leadership, governance, and accountability for integrating and promoting SDH throughout the organization are also necessary. For example, during the past decade, health equity offices and accountable executives have been established across NCHHSTP, including many of the larger divisions (Figure). These health equity offices/teams/focal points provide a locus for the coordination, tracking, reporting, and promotion of health equity and SDH within organizational units. A Center-wide health equity workgroup was established, with full participation of senior scientists from all parts of NCHHSTP, to promote collaboration, synergy, and sharing of promising approaches. Technical workgroups focusing on populations or settings (e.g., corrections, people who use drugs, young people, and men who have sex with men) helped to promote greater strategic, scientific, and programmatic focus on population health and SDH. Providing the space and support for SDH leadership and expertise helped raise the profile of this emerging area while tangibly demonstrating, both internally and externally, NCHHSTP's commitment to SDH. Finally, for all NCHHSTP health equity activities, robust reporting requirements were instituted with annual reporting, publication, and dissemination of performance reports, which aided monitoring and evaluation efforts.

Figure.

NCHHSTP organizational structure for health equity

NCHHSTP = National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention

DVHP = Division of Viral Hepatitis Prevention

DSTDP = Division of STD Prevention

DASH = Division of Adolescent and School Health

DHAP = Division of HIV/AIDS Prevntion

DTBE = Division of Tuberculosis Elimination

OHE = Office of Health Equity

MSM = men who have sex with men

HIV/AIDS = human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

STD = sexually transmitted disease

TB = tuberculosis

Data systems

The importance of improving data collection and measurement systems to include SDH data has been noted as key to advancing the core public health functions of assessment, assurance, and policy.9,18 A review of NCHHSTP surveillance systems for HIV, viral hepatitis, STDs, and TB was conducted to understand current efforts to collect SDH variables and to make suggestions for possible areas to focus collection efforts in the future.19 Statistical methods to model the SDH using case surveillance data and the American Community Survey data were developed to determine the impact of SDH on disease rates.20,21 The methods have proven useful in correlating demographic and SDH variables.

NCHHSTP developed an SDH activities report to describe existing activities that specifically focus on and address SDH, with a goal of assessing progress and identifying gaps for future planning.22 The long-term goal is to systematically collect this information annually to inform the allocation of programmatic, research, and other Center resources by SDH categories and provide Center-wide guidance for the selection of activities that target broader aspects of disease prevention for increased public health impact.22,23

Key priorities for enhancing NCHHSTP surveillance systems have included expanding the collection of sexual orientation data for HIV and STDs in enhanced and behavioral surveillance systems; integrating, analyzing, and reporting on community and societal levels and determinants of disease transmission in addition to the individual-level determinants; leveraging and using data from population-based surveys to enhance the interpretation of traditional clinic-based surveillance systems; and using a range of data to explore geographic patterns, distribution, and concentration of disease incidence and its correlation with a range of social and structural determinants. Over time, it is hoped that there will be greater consistency in the collection and reporting of SDH indicators across the NCHHSTP's disease surveillance programs with consistency in approaches used to characterize and describe SDH.

Agency partnerships

As a national public health agency, CDC does not and cannot tackle all the major social and structural determinants on its own; therefore, engaging traditional and new partners to create effective coalitions has been a key strategy. NCHHSTP developed a strategic approach to partner engagement for SDH including partnerships with other federal agencies, businesses, civil society, and grantees.

Strong interagency partnerships were key for the successful development of both the National HIV/AIDS Strategy and the HHS Viral Hepatitis Action Plan, in which CDC played strong leadership roles. Both strategies acknowledge and integrate health equity and have driven stronger interagency partnership and collaboration.15,24 As these national strategic plans are being implemented by various agencies, novel initiatives that integrate traditional and syndemic approaches (e.g., the Enhanced Comprehensive HIV Prevention Planning [ECHPP] Project) or integrate SDH into prevention programs (e.g., the Care and Prevention in the United States Demonstration Project [CAPUS]) have emerged. CAPUS is a three-year, cross-agency project led by CDC that aims to reduce HIV- and AIDS-related morbidity and mortality among racial/ethnic minority groups living in the U.S. The two primary goals of the project are to increase the proportion of racial/ethnic minority individuals with HIV who have diagnosed infection by expanding and improving HIV testing capacity; and to optimize linkage to, retention in, and reengagement with care and prevention services for newly diagnosed and previously diagnosed racial/ethnic minority individuals with HIV. These two goals are to be achieved by addressing social, economic, clinical, and structural factors influencing HIV health outcomes.

Other initiatives have involved partnerships with nontraditional partners to increase the focus on health equity and SDH. The Act Against AIDS Leadership Initiative (AAALI)—a $16 million, six-year partnership among CDC and leading national organizations representing the populations hardest hit by HIV—was launched as part of the Act Against AIDSTM communication campaign in 2009. The initiative originally brought together some of the nation's foremost African American organizations to intensify HIV prevention efforts in black communities. In 2010, CDC expanded AAALI to also include organizations that focus specifically on men who have sex with men (MSM) and the Latino community. Partnerships such as these have enabled a broader group of constituencies to engage on HIV issues, discuss and educate their networks about health equity and the importance of SDH, and employ other sectors to address the epidemic more comprehensively.

Direct engagement of the scientific and public health practice has also proved an effective strategy. Ongoing site visits by NCHHSTP leaders to programs across the country facilitated direct engagement with grantees about health equity and SDH. Conference presentations, symposia, and plenaries provided opportunities to discuss NCHHSTP health equity, and SDH activities have actively promoted awareness, debate, and action in the scientific and programmatic community. During 2012, NCHHSTP launched a series of Community Engagement Sessions at six sites across the U.S. to discuss MSM sexual health. These sessions provided a direct opportunity for NCHHSTP leadership to meet with local leaders in health departments, community-based organizations, and the general public to honestly discuss the worsening trends in MSM sexual health and its social and structural determinants. As a result of these discussions, the Center will refine current programming and provide additional technical support to grantees to enhance their health equity activities.

Capacity building

Given NCHHSTP's recent adoption and implementation of this more strategic approach to health equity and SDH, strategies to educate and engage internally (i.e., NCHHSTP staff) and externally (i.e., grantees, partners, and policy makers) have been essential. New terminology, concepts, and approaches had to be explained clearly; specific required and recommended actions had to be determined; and, where applicable, funding support had to be identified. NCHHSTP used a variety of methods, including consultations, symposia, and webinars, to aid its capacity-building efforts.

In 2009, NCHHSTP hosted a consultation on correctional health—Corrections and Public Health, Expanding the Reach of Prevention. The goals of the consultation were to assist in the development of NCHHSTP priorities that will enhance the provision of infectious disease prevention services in correctional settings; provide suggestions for continuity of care and linkage back to the community; develop an adaptable strategy for reducing the burden of infectious disease within correctional settings; develop suggestions that can guide policies, programs, and research efforts for correctional settings; and identify models of best practices for integrating improved public health programs into correctional settings. This forum provided an opportunity for subject-matter experts from various sectors of the correctional system, public health, academia, and community partners to develop more effective ways to address several important issues, including health disparities in HIV, viral hepatitis, STD, and TB among people who are incarcerated.25

In 2010, CDC convened the Public Health and Homelessness symposium to highlight CDC work related to homelessness. The symposium served as an avenue to facilitate the development of a network of CDC scientific and programmatic staff whose collective work can contribute to the agency's ability to reduce the health risks associated with homelessness, improve the quality of life of affected people, and potentially enhance the work of other federal agencies that strive to prevent and reduce the incidence of homelessness. The symposium also provided a forum for CDC staff to examine ways to improve public health services for the homeless through state and local health departments.

NCHHSTP also held two symposia aimed at building capacity for CDC staff to understand the link between SDH and optimal health; address SDH in public health practice, policy, and research; and discuss the role of data systems and SDH. In 2010, NCHHSTP hosted a symposium entitled Establishing a Holistic Framework to Reduce Inequities in Human Immunodeficiency Virus, Viral Hepatitis, Sexually Transmitted Diseases, and Tuberculosis in the United States. The purpose of the symposium was to discuss topics related to addressing SDH in public health practice, policy, and research, and to focus on how NCHHSTP can further incorporate an SDH approach into its work.26 In 2011, NCHHSTP hosted a Healthy Equity symposium focused on increasing CDC staff awareness, engagement, and action to address SDH and to highlight the role of data in informing and improving public health policy, practice, and research. More than 300 staff members from across CDC attended the symposium. A summary of the symposium can be found in this supplement.27

Finally, all conferences funded by NCHHSTP (e.g., the National HIV Prevention Conference and the National STD Prevention Conference) were required to incorporate strong health equity and SDH activities to promote scientific dialogue, information exchange, and promising practices. In specific conference tracks focusing on health equity, cross-cutting themes, plenary presentations, symposia, or workshops, the Center's technical divisions played an important role in ensuring that health equity remained on the scientific agenda and that grantees and participants would be supported and encouraged to contribute to the scientific discourse.

Prevention research and evaluation

NCHHSTP published three Public Health Reports supplements focused on SDH and their intersection with public health. The first, Addressing Social Determinants of Health in HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, Sexually Transmitted Diseases, and Tuberculosis, published in June 2010, focused on innovations, advances, and insights regarding the role of social determinants in the spread of HIV, viral hepatitis, sexually transmitted infections, and TB. The second, Data Systems and Social Determinants of Health, published in August 2011, focused on data systems and their use in addressing SDH. Finally, the third is this supplement, Applying Social Determinants of Health to Public Health Practice.18,28,29

Health communication

During the past five years, a number of health communications awareness-building products were developed for internal and external audiences. A new SDH website was developed to serve as an information source, point of contact, and sharing portal for national and international stakeholders interested in addressing SDH.30 A glossary of terms regarding health equity and SDH, a fact sheet with frequently asked questions, and a brief training slide set have been developed for the CDC community. SDH language was added to press releases and surveillance reports to acknowledge the impact of social and structural determinants of health on disease rates.31–33

NCHHSTP launched communication campaigns aimed at increasing HIV awareness among groups with the highest rates of HIV and an anti-stigma campaign featuring people living with HIV and their friends and family. One example is the Act Against AIDS initiative—a five-year national campaign, which is a collaborative effort with the White House to combat complacency about HIV and AIDS in the U.S. Launched in 2009, the initiative focuses on raising awareness among all Americans and reducing the risk of infection among the hardest-hit populations—gay and bisexual men, African Americans, Latinos, and other communities at increased risk. The Act Against AIDS initiative also supports the AAALI—a network of national-level organizations that focus on African Americans, black MSM, and the Latino community—to deliver campaign messages and conduct community outreach activities. It is anticipated that this partnership will have an impact on the social context of HIV transmission in these communities. The Act Against AIDS initiative consists of several concurrent HIV prevention campaigns and uses mass media (e.g., television, radio, newspapers, magazines, and the Internet) to deliver important HIV prevention messages.34

CONCLUSIONS

Developing and implementing new strategic approaches to promote health equity and address SDH has been an essential component of NCHHSTP's commitment to advancing more syndemic approaches to prevention in which the individual, health system, and social influences on disease, health, and well-being are acknowledged and addressed comprehensively. Developing overarching agency and national strategic plans was critical to providing supportive policy frameworks for enhanced action in this domain. For effective implementation, focused attention on capacity building, leadership and governance, strategic partnerships, and effective health communication all helped to generate awareness, stimulate new dialogue, and enable more effective sharing of promising practices. More recently, discrete new funding opportunities, which call for and integrate addressing SDH in prevention programming, have enabled NCHHSTP to move from theory to practice and action. Keys to success in this journey have been strong leadership at every level of the organization to guide, monitor, and be held accountable for real change in addressing health equity and SDH; clearly articulate the rationale and value proposition of adopting this more comprehensive approach; and allay fears and concerns that incorporating SDH will not take away or diminish traditional vertical programming. In contrast, disease-specific efforts can be enhanced by addressing root causes, engaging broader partners, leveraging new resources, and improving sustainability. As a science-based public health agency, ensuring that our work in health equity and SDH is based on the best available science, and ensuring that we continue to invest in and learn from research, is important for the credibility of our agency and scientists, and will be critical for the continued evolution of this initiative.

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

REFERENCES

- 1.Satterwhite CL, Torrone E, Meites E, Dunne EF, Mahajan R, Ocfemia MC, et al. Sexually transmitted infections among U.S. women and men: prevalence and incidence estimates, 2008. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40:187–93. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318286bb53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Owusu-Edusei K, Jr, Chesson HW, Gift TL, Tao G, Mahajan R, Ocfemia MC, et al. The estimated direct medical cost of selected sexually transmitted infections in the United States, 2008. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40:197–201. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318285c6d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tarlov AR. Public policy frameworks for improving population health. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;896:281–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dean HD, Fenton KA. Addressing social determinants of health in the prevention and control of HIV/AIDS, viral hepatitis, sexually transmitted infections, and tuberculosis. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(Suppl 4):1–5. doi: 10.1177/00333549101250S401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization, Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva: WHO; 2008. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Final report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. Final report of the World Conference on Social Determinants of Health [cited 2012 Dec 26] Available from: URL: http://www.who.int/sdhconference/resources/wcsdh_report/en/index.html.

- 7.Satcher D. Include a social determinants of health approach to reduce health inequities. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(Suppl 4):6–7. doi: 10.1177/00333549101250S402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDavid Harrison K, Dean HD. Use of data systems to address social determinants of health: a need to do more. Public Health Rep. 2011;126(Suppl 3):1–5. doi: 10.1177/00333549111260S301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sadana R, Harper S. Data systems linking social determinants of health with health outcomes: advancing public goods to support research and evidence-based policy and programs. Public Health Rep. 2011;126(Suppl 3):6–13. doi: 10.1177/00333549111260S302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koh HK. The ultimate measures of health. Public Health Rep. 2011;126(Suppl 3):14–5. doi: 10.1177/00333549111260S303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharpe TT, McDavid Harrison K, Dean HD. Summary of CDC consultation to address social determinants of health for prevention of disparities in HIV/AIDS, viral hepatitis, STD, and tuberculosis. Dec. 9–10, 2008. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(Suppl 4):11–5. doi: 10.1177/00333549101250S404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, sexually transmitted diseases, and TB Prevention strategic plan, 2010–2015. Atlanta: CDC; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) NCHHSTP strategic priorities dashboard 2012–2013 [cited 2012 Dec 26] Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/strategicpriorities.

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) DHAP strategic plan [cited 2012 Dec 26] Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/strategy/dhap/index.htm.

- 15.Department of Health and Human Services (US) Combating the silent epidemic of viral hepatitis: action plan for the prevention, care and treatment of viral hepatitis [cited 2012 Dec 25] Available from: URL: http://www.hhs.gov/ash/initiatives/hepatitis/actionplan_viralhepatitis2011.pdf.

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Social determinants of health: an NCHHSTP white paper [cited 2012 Dec 26] Available from: URL: http://www.nchhstp.cdc.gov/OD/docs/At-A-Glance/Social-determinants-At-A-Glance.pdf.

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Establishing a holistic framework to reduce inequities in HIV, viral hepatitis, STDs, and tuberculosis in the United States. Atlanta: CDC; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDavid Harrison K, Dean HD, editors. Data systems and social determinants of health. Public Health Rep. 2011;126(Suppl 3):1–126. doi: 10.1177/00333549111260S301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beltran VM, McDavid Harrison K, Hall HI, Dean HD. Collection of social determinant of health measures in U.S. national surveillance systems for HIV, viral hepatitis, STDs, and TB. Public Health Rep. 2011;126(Suppl 3):41–53. doi: 10.1177/00333549111260S309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song R, Hall HI, McDavid Harrison K, Sharpe TT, Lin LS, Dean HD. Identifying the impact of social determinants of health factors on disease rates using correlation analysis of area-based summary information. Public Health Rep. 2011;126(Suppl 3):70–80. doi: 10.1177/00333549111260S312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moonesinghe R, Fleming E, Truman BI, Dean HD. Linear and non-linear associations of gonorrhea diagnosis rates with social determinants of health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012;9:3149–65. doi: 10.3390/ijerph9093149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Activities related to the social determinants of health, fiscal year 2009. Atlanta: CDC; 2010. Also available from: URL: http://www.nchhstp.cdc.gov/od/OHE/docs/SDH-Activities-Report-111910.pdf [cited 2012 Dec 26] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Activities related to the social determinants of health, fiscal year 2011. Atlanta: CDC; 2011. Also available from: URL: http://www.nchhstp.cdc.gov/od/OHE/docs/FY11-SDH-ActivitiesReport_Final.pdf [cited 2012 Dec 26] [Google Scholar]

- 24.White House (US) National HIV/AIDS strategy for the United States. 2010 [cited 2012 Dec 26] Available from: URL: http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/uploads/NHAS.pdf.

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) A technical consultation report. Atlanta: CDC; 2011. Corrections and public health: expanding the reach of prevention. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Colbert S, McDavid Harrison K. Reflections from the CDC 2010 Health Equity Symposium. Public Health Rep. 2011;126(Suppl 3):38–40. doi: 10.1177/00333549111260S308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Penman-Aguilar A, McDavid Harrison K, Dean HD. Identifying root causes of health inequities: reflections on the 2011 National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention Health Equity Symposium. Public Health Rep. 2013;128(Suppl 3):29–32. doi: 10.1177/00333549131286S305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dean HD, Fenton KA, editors. Social determinants of health. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(Suppl 4):1–121. doi: 10.1177/00333549101250S401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dean HD, Williams KM, Fenton KA, editors. Applying social determinants of health to public health practice. Public Health Rep. 2013;128(Suppl 3):1–116. doi: 10.1177/00333549131286S301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Social determinants of health [cited 2012 Dec 26] Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/socialdeterminants.

- 31.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) More than half of young HIV-infected Americans are not aware of their status [cited 2012 Dec 26] Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2012/p1127_young_HIV.html.

- 32.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) New HIV infections in the United States [cited 2012 Dec 26] Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/2012/HIV-Infections-2007-2010.pdf.

- 33.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) HIV surveillance report, vol. 22. Diagnoses of HIV infection and AIDS in the United States and dependent areas, 2010 [cited 2012 Dec 26] Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/surveillance/resources/reports/2010report/index.htm.

- 34.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Act Against AIDSTM [cited 2012 Dec 26] Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/actagainstaids.