Abstract

Federal, state, and local labor laws establish minimum standards for working conditions, including wages, work hours, occupational safety, and collective bargaining. The adoption and enforcement of labor laws protect and promote social, economic, and physical determinants of health, while incomplete compliance undermines these laws and contributes to health inequalities. Using existing legal authorities, some public health agencies may be able to contribute to the adoption, monitoring, and enforcement of labor laws. We describe how routine public health functions have been adapted in San Francisco, California, to support compliance with minimum wage and workers' compensation insurance standards. Based on these experiences, we consider the opportunities and obstacles for health agencies to defend and advance labor standards. Increasing coordinated action between health and labor agencies may be a promising approach to reducing health inequities and efficiently enforcing labor standards.

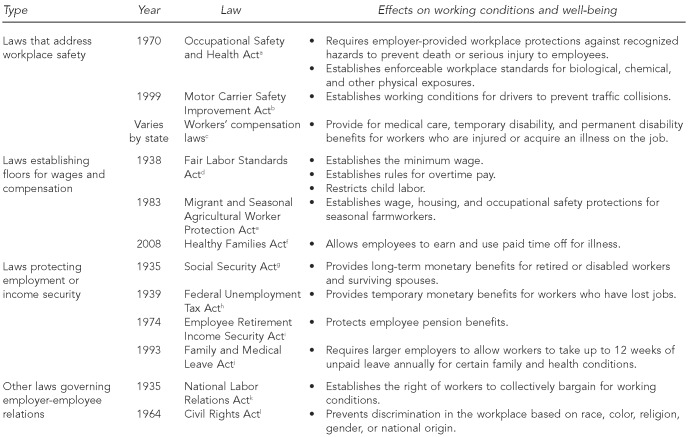

Laws and standards on working conditions, including those for the minimum wage, the eight-hour work day, workplace safety, child labor, and collective bargaining, exist to prevent involuntary hazards and to assure that compensation for workers is sufficient to meet their basic economic needs. These working conditions are also understood to be social, economic, and physical determinants of health and health inequalities.1,2 The minimum wage, for example, serves to assure a minimum income. Income is a prerequisite for nutrition, housing, transportation, and leisure,3–5 and is associated positively with health outcomes, including longevity.6–8 The adoption and enforcement of occupational health safety standards similarly prevents work-related injuries.9 Figure 1 provides a brief overview of key labor laws that impact worker health and well-being.

Figure 1.

Key U.S. labor laws that impact working conditions and employee well-being

aPub. L. No. 91-596, 84 Stat. 1590 (December 29, 1970).

bPub. L. No. 106-159, 113 Stat. 1748-1773 (December 9, 1999).

cLaws governing workers' compensation established and implemented at the state level

d29 U.S.C. Ch. 8 (1938).

ePub. L. No. 97-470 (January 14, 1983).

fThis law has been proposed but not adopted at the federal level. Similar paid sick day laws have been adopted at the state and local level.

gPub. L. No. 74-271, 49 Stat. 620 (August 14, 1935).

hPub. L. No. 76-379 (1939).

iPub. L. No. 93-406, 88 Stat. 829 (September 2, 1974).

jPub. L. No. 103-3, 107 Stat. 6 (February 5, 1993).

kPub. L. No. 74-198, 49 Stat. 449 (July 5, 1935).

lPub. L. No. 88-532, 78 Stat. 241 (July 2, 1964).

Although most labor laws have existed for decades, many workers, particularly immigrants and those in low-wage positions, may not benefit from them.10,11 Some workers routinely experience nonpayment of wages and other labor violations.12 Of 4,387 workers surveyed in New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago, 26% were illegally paid less than minimum wage, 68% had at least one pay-related violation in the past week, and one in five workers who either made a complaint to an employer or tried to form a union experienced retaliation.13 Similarly, hazardous working conditions and preventable occupational exposures, injuries, and deaths are prevalent, particularly among people of color, immigrants, and others who are disproportionately employed in low-wage and nonunionized jobs.13–16 Unsafe working conditions and labor rights violations may generate further vulnerability to poor health outcomes through higher levels of stress and limited access to basic needs, such as affordable and quality housing, education, food, transportation, and medical care.3

Despite incomplete compliance, during the past three decades, agencies responsible for labor standards enforcement have experienced a decline in their resources and capacity.17,18 Political and economic factors have also played a role in weakening labor protections.1,19 Reversing these trends will require new fiscal and political commitments.

Collaboration among regulatory agencies, each with particular mandates and roles, is one potentially efficient and effective means to increase enforcement capacity. As a local public health agency, the San Francisco Department of Public Health (SFDPH) regulates multiple health and safety conditions in local businesses. In 2009, following demand from community organizations, SFDPH began to use its regulatory authority to protect labor rights. The initial focus was on restaurants—one of the largest city employers of low-wage workers and the frequent subject of labor rights complaints. This article describes the current local and federal context of labor law enforcement and, using two case studies, describes SFDPH activities to support labor law compliance. We then consider the obstacles and opportunities for public health agencies to advance and protect healthy labor standards and healthy working conditions.

PURPOSE

The decline in capacity of federal and state labor standards enforcement agencies is evident in the reduction in number of regulators relative to workers and workplaces and in the shift to reactive enforcement. From 1975 to 2004, the number of covered workplaces increased by 112%, while the number of staff investigators decreased by 14%.18 In 1975, there was one occupational safety inspector for every 27,845 workers; in 2011, there was one inspector for every 57,984 workers.17

Although proactive or “directed” investigations were common in the past, in 2010, more than 70% of all enforcement cases involving alleged violations of wage laws were complaint driven.20 Proactive investigations, where they occur, focus on larger employers and high-risk industries. Workers in industries with the worst labor conditions may be less likely to issue complaints to enforcement agencies.21

Existing penalties also may not provide sufficient disincentives against violations. From 1970 to 2010, there were more than 360,000 worker deaths across the United States. During this time, the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) reports that only 84 cases of worker death resulted in civil or criminal prosecution, with defendants serving a total of 89 months in jail.17 In 2010, the average federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) penalty was $1,052, and the median initial penalty per worker death was $5,900. The maximum civil penalty that OSHA can charge for a worker's death is $70,000, compared with a maximum civil penalty of $270,000 for violations of the Clean Air Act, $325,000 for indecent content on a TV or radio station, or $1 million for tampering with a public water source.9

Strong political support for deregulation has also been evident during the past decades.19,20 Federal legislative efforts to remove barriers to union formation and collective bargaining, such as the Employee Free Choice Act,22 have encountered strong opposition. Several U.S. states have proposed right-to-work laws, which may adversely affect wages, employment, and benefits by eroding collective bargaining rights.23–27 Loomis and colleagues found that states with right-to-work laws, low union membership density, and low labor grievance rates were more likely to have higher rates of fatal occupational injury than states with higher union membership.28

Broader economic forces are also contributing to weakening of labor standards.29 Competition among employers to lower labor costs is a key force behind efforts to weaken or avoid regulations. Subcontracting and the shift to temporary and part-time work results in fewer workers protected by laws that cover full-time, permanent employees. Unions play a key role in monitoring and enforcing compliance with labor laws, and declining union membership may diminish this function.

Despite these unfavorable administrative, political, and economic trends, DOL, along with worker and legal advocates, has recently been working to strengthen federal and state enforcement of labor standards through administrative and policy actions.30 For example, DOL has strengthened worker protections in the temporary non-agricultural worker visa program31 and for home health-care workers who historically were excluded from minimum wage and overtime protections.32 In 2010, DOL publicly released enforcement data of four federal agencies to increase transparency and public access to violations data.33 Since 2011, DOL has signed memorandums of understanding with 12 states to address worker misclassification.34 DOL's fiscal year 2013 budget illustrates a commitment to “spur economic growth and promote workers' rights, enforce statutory rules that keep workers safe, and help workers keep what they earn,” and includes requests for $15 million for additional enforcement staff, $6 billion in training and employment programs, and $125 million for a Workforce Innovation Fund.35

Additional monitoring of labor compliance by diverse local and state regulatory agencies could be an efficient means to complement these federal initiatives. Coordinated code enforcement is a commonly used strategy in several contexts. For example, the Office of the City Attorney in San Francisco coordinates inspection and enforcement activities when properties are subjects of multiple complaints to housing, building, fire, police, and planning departments. Through such coordinated, interagency efforts, staff members learn to recognize and monitor compliance outside their own agency's regulatory mandates and become able to facilitate action by partner agencies.

METHODS AND OUTCOMES

Case study 1: health agency enforcement of unpaid wage violations

In San Francisco, the Office of Labor Standards Enforcement (OLSE) enforces violations of local labor laws, including the local minimum wage standard ($10.24/hour in 2012) and a law guaranteeing the accrual and use of paid sick leave. OLSE responds to complaints from workers for nonpayment or underpayment of wages. Investigations can lead to a judgment against the employer and an order for the employer to pay wages owed and additional penalties. Typically, recovering wages or penalties is time consuming and can require civil litigation. As an alternative enforcement approach, OLSE can also request that other city agencies revoke or suspend permits of employers who do not comply with local labor laws.

SFDPH thought restaurants might be a good context to test coordinated code enforcement strategies with OLSE. Restaurants are overrepresented in wage-enforcement cases nationally.20 In San Francisco, about one-third of OLSE cases are complaints against restaurant employers. Surveys of restaurant workers in San Francisco's Chinatown found that 50% of workers were not receiving minimum wage.36

SFDPH issues permits to restaurants and conducts routine inspections to ensure safe food practices. SFDPH has the authority to revoke or suspend a permit not only when a food establishment exhibits unsafe food practices, but also when a business violates any other local, state, or federal law.37 The potential suspension or revocation of a permit can be a significant financial disincentive for a business, and this administrative sanction can be invoked more rapidly than the civil enforcement tools otherwise available to OLSE.

In 2010, OLSE leveraged SFDPH's permit authority to compel resolution of a case of underpayment of wages to five restaurant workers. After an investigation conducted in 2006, OLSE ordered the employer to pay owed wages with penalties, yet the employer failed to pay the full amount owed despite hearings and appeals. In 2010, OLSE requested that SFDPH suspend the permit until payment was made. Regulatory staff from both agencies jointly prepared and presented evidence on the case to the hearing officer, who ordered the owner to pay owed wages and penalties. Within four months of the Director of Health's orders, the workers received the money owed to them.

OLSE has subsequently used SFDPH's authority to compel compliance in additional wage cases. SFDPH and OLSE are exploring other coordinated strategies for labor standards compliance. For example, SFDPH is requiring new food operators to acknowledge their responsibility to comply with labor laws as a condition of obtaining a new restaurant permit. SFDPH and OLSE are considering whether they should target compliance monitoring based on both food safety inspections and employee labor standards complaints. SFDPH is also considering additional sanctions on businesses with chronic labor code violations confirmed by labor agency rulings.

Case study 2: routine monitoring of workers' compensation insurance

All businesses in California are required to maintain workers' compensation insurance that pays for medical care and disability benefits when workers acquire a job-related injury or illness.38 Many employers do not carry insurance or do not carry sufficient insurance for all employees.13 Inadequate insurance creates a barrier to workers getting timely or preventive care for job injuries and disability benefits to replace lost wages when injured.39

In 2010, SFDPH began requiring restaurant operators to provide proof of workers' compensation insurance when they applied for permits. Existing businesses received a warning that failure to provide proof of workers' compensation insurance could prevent permit renewal. To proactively enforce the new rule, SFDPH requested proof of coverage from a random sample of permitted businesses. SFDPH then withheld the permit renewal if a business did not provide proof of coverage.

Of businesses in the first sample, 10% did not have workers' compensation insurance prior to SFDPH's request for proof of coverage. While some acquired insurance after this request, 4% did not provide proof of coverage until SFDPH threatened to suspend their permits. After being compelled to attend public hearings, all businesses except one provided proof of insurance coverage. SFDPH is currently studying additional ways to incorporate monitoring of occupational health and safety conditions into the routine tasks of field inspectors.

LESSONS LEARNED

Labor laws exist to ensure minimally acceptable physical and economic working conditions. These conditions have direct and indirect influences on human needs fulfillment and human health, and, thus, should be considered health determinants. There is a long history of occupational medicine advocating for and establishing such laws.

Interagency collaboration to support labor code enforcement: opportunities and barriers

SFDPH's work illustrates opportunities for local public health agencies to use their authority to support oversight and enforcement of labor laws. Simply put, public health agencies can treat failures to adhere to labor laws or comply with administrative labor rule as violations of general conditions under which the permit was granted. Public health laws governing restaurant operation in California provide explicit authority for such actions. The use of administrative enforcement mechanisms available to public health agencies may be considerably more efficient than those available to labor agencies.

Notably, we could not identify any published reports on similar interventions involving public health agency monitoring or enforcing labor standards. The lack of action by public health on labor standards may reflect the lack of practical models, limited working relationships between public health and labor agencies, or, more simply, the absence of attention by public health to labor issues.

We acknowledge that public health agencies may have reasons to oppose participation in labor regulation. For example, the New York City Department of Public Health (NYCDPH) testified against the 2008 Restaurant Responsibility Act, which would have required restaurants to disclose affirmed wage and hour violations and NYCDPH to consider violations in the decision to grant permit renewals. NYCDPH argued that wage and hour standards did not have public health significance and that labor regulation would compete with the agency's focus on food safety.40 Despite competing testimony and arguments from council members, restaurants, and the public, the Act was “laid over” by the New York City Council Committee on Health, and no further action was taken.41

Limited direct evidence on labor laws and health may be a potent barrier to replication of the San Francisco initiative. While there is a substantial body of evidence linking working conditions—including the use of protective equipment, the right to paid sick leave, and the degree of job control—with human health,2 the impact of labor laws on health is not a typical subject of empirical scrutiny. Labor laws are clearly enacted to benefit public welfare; however, the study of regulation often focuses on issues of compliance, business behaviors, and regulatory costs and not on the welfare outcomes.42–44 Study of the effectiveness of labor laws and their enforcement on health outcomes may be necessary to stimulate public health agencies to participate in their realization.

Segregation of responsibilities among and within institutions is another deeply entrenched characteristic of public bureaucracies limiting coordinated enforcement; however, there are also promising examples of interagency collaboration. At the federal level, the development of a National Prevention Strategy through a 17-agency National Prevention Council45 and the promotion of green jobs through collaborations between the federal Departments of Labor, Education, Energy, and Housing and Urban Development46 are concrete examples. At the state level, California recently created the Labor Enforcement Task Force,47 involving six state bodies and local district attorneys to target the underground economy; New York48 and Michigan49 have established interagency bodies to address worker misclassification; and coalitions on occupational safety and health in various states have helped bring together local labor, health, and safety organizations.50

In San Francisco, a key condition supporting interagency coordination and collaboration was the leadership within the environmental health and labor agencies. Initially, some restaurant inspectors raised concerns that increasing the agency's focus on labor law could dilute attention to food safety and sour their relationships with business owners. These inspectors initially opposed expansion of the scope of restaurant regulation; however, both agencies now routinely brainstorm new ways to collaboratively solve problems. Additional contributing factors in local experience include advocacy for coordinated action from organized stakeholders, a public health agency mission inclusive of social and economic determinants of health, and a small and innovative local labor standards office.

Engaging public health institutions in labor standards protection may require overcoming more general public perceptions that labor law enforcement is undesirable or antibusiness, particularly in the current economic climate. Regardless of anti-regulatory rhetoric, most businesses do comply with labor rules and consider that noncompliance by a competitor creates an unfair business practice.29,51 Employer violations of employment and labor law have significant economic costs to society. In Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York City, wage theft is estimated to cost low-wage workers and their cities $56.4 million per week.13 Reports by federal and state agencies affirm that employer noncompliance with wage and hour rules not only undermines workers' economic security but also increases the expenses of public safety nets.11,51,52 One study found that if all workers in California earned a minimum of $8 per hour, the state's 10 largest public assistance programs would save $2.7 billion per year.53

Opportunities for other public health actions for healthy workplaces

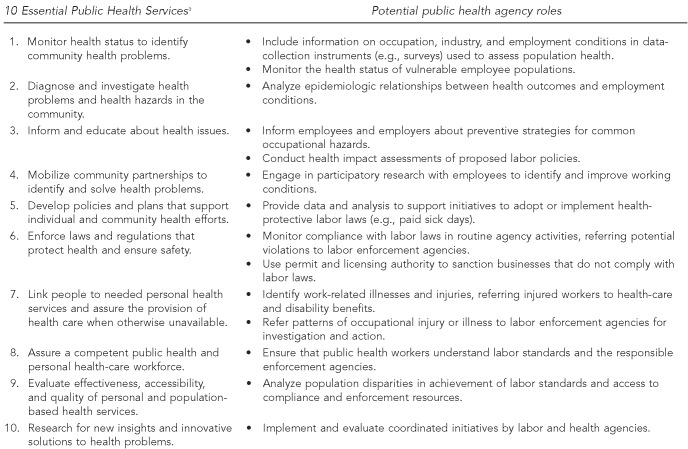

Public health agencies can support healthful workplace conditions in ways other than direct participation in labor enforcement activities. As illustrated in Figure 2, strategies for public health authorities to support working conditions correspond to well-established public health functions.

Figure 2.

Potential roles for public health agencies in supporting health-protective labor standards in the U.S.

aCenters for Disease Control and Prevention (US), National Public Health Performance Standards. The public health system and the 10 essential public health services [cited 2013 Jul 5]. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/nphpsp/essentialservices.html

Monitoring health conditions attributable to working conditions and conducting research linking working conditions to health outcomes are core functions of public health authorities. Dissemination of these data and analyses could support attention to labor violations and lead to enhanced enforcement efforts or needed policy change. Such monitoring and assessment requires more routine incorporation of -information on occupational status and working conditions in data-collection instruments. In 2011, a panel convened by the Institute of Medicine found that “occupational information could contribute to fully realizing the meaningful use of electronic health records in improving individual and population health care.”54

Public health agencies can also play a role in educating workers about their legal rights and how to access those rights. Participatory research and education initiatives conducted with vulnerable workers, including farmworkers, home health-care workers, day laborers, poultry workers, and nail salon workers, have contributed to an increased understanding of how workers can protect themselves and others on the job. These activities also result in policy changes needed to promote health and safety.55 In San Francisco, research conducted with restaurant workers documenting violations of minimum wage laws was instrumental in motivating the coordinated enforcement efforts described in this article.36,56

Initiatives that inform consumers about either poorly performing or high-performing businesses may also be an effective way to change culture. Public disclosure of restaurant safety scores has been credited with decreasing the transmission of foodborne illness in restaurants57 and improving employer practices.58,59 A number of local jurisdictions have launched healthy food initiatives to promote healthy menu options and healthy eating in restaurants.60

Voluntary initiatives recognize businesses that perform at a high standard of environmental or social responsibility. Internationally, fair trade certification and labeling recognize products whose production practices are responsible to workers. Organizations such as the Restaurant Opportunities Center have begun working with employers who take the “high road to profitability” as part of a Restaurant Industry Roundtable to “promote sustainable business practices for employees and consumers while boosting their bottom line.”61 Environmental organizations such as Green Seal and Green America have launched programs to recognize food and other businesses with better environmental practices. New initiatives at the local to national level in the U.S. could be designed to recognize businesses that provide workers with living wages or health-supportive benefits.

Finally, health impact assessments (HIAs) can help advance health-protective labor policies. In 1999, SFDPH conducted an assessment of the potential health benefits of a living wage ordinance, using available epidemiologic and economic data to estimate the expected health effects of an increased minimum wage for employees of city contractors and leaseholders.6 In 2009, the nonprofit organization Human Impact Partners conducted an HIA on a federal legislative mandate for sick days.62 These HIAs appear to have improved awareness and understanding of how policies affecting labor conditions also affect health, cultivating public health advocate support for these policy initiatives.63

CONCLUSION

Interagency collaboration among local, state, and federal government agencies—as well as collaboration with community-based organizations and the private sector—is a promising mechanism of efficiently meeting regulatory commitments in a resource-constrained environment. Local health departments can support compliance with labor laws by monitoring working conditions, educating workers and employers, using existing enforcement authorities, and recognizing exemplary businesses. Improving working conditions should be viewed as a key function of public health.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the following individuals for their contributions to the work described in this article: Donna Levitt and her staff at the San Francisco Office of Labor Standards Enforcement; Amelia Castelli, John Castelli, Mary Freschet, Jacki Greenwood, Pamela Hollis, Terrence Hong, Richard Lee, Mohammed Malhi, Eric Mar, Timothy Ng, Lisa O'Malley, Imelda Reyes, Alicia Saam, Calvin Tom, Kenny Wong, and other San Francisco Department of Public Health (SFDPH) environmental health inspection staff; Shaw San Liu, Tiffany Crane, Josue Arguelles, Charlotte Noss, and other members of the San Francisco Progressive Workers Alliance; Tomas Aragon, SFDPH Health Officer; and Meredith Minkler, Pam Tau Lee, Charlotte Chang, Alicia Salvatore, Niklas Krause, Fei-Ye Chen, Alex Tom, and others on the Chinatown Restaurant Worker Health Project.

REFERENCES

- 1.Benach J, Muntaner C, Santana V Employment Conditions Knowledge Network. Final report to the World Health Organization Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva: WHO; 2007. Employment conditions and health inequalities. Also available from: URL: http://www.who.int/social_determinants/resources/articles/emconet_who_report.pdf [cited 2012 Feb 20] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siqueira CE, Gaydos M, Monforton C, Fagin K, Slatin C, Borkowski L, et al. Effects of social, economic, and labor policies on occupational health disparities. Presented at the First National Conference on Eliminating Health and Safety Disparities at Work; 2011 Sep 14–15; Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization, Commission on Social Determinants of Health. CSDH final report. Geneva: WHO; 2008. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braveman P, Eggler S. Overcoming obstacles to health. Report from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to the Commission to Build a Healthier America. 2008 [cited 2012 Feb 20] Available from: URL: http://www.commissiononhealth.org/PDF/ObstaclesToHealth-Report.pdf.

- 5.Evans GW. The environment of childhood poverty. Am Psychol. 2004;59:77–92. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.2.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhatia R, Katz M. Estimation of health benefits from a local living wage ordinance. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1398–402. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.9.1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fairris D, Reich M. The impacts of living wage policies: introduction to the special issue. Ind Relat. 2005;44:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lipscomb HJ, Loomis D, McDonald MA, Argue RA, Wing S. A conceptual model of work and health disparities in the United States. Int J Health Serv. 2006;36:25–50. doi: 10.2190/BRED-NRJ7-3LV7-2QCG. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Department of Labor (US), Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Testimony of David Michaels, Assistant Secretary for Occupational Safety and Health, U.S. Department of Labor before the Subcommittee on Workforce Protections, the Committee on Education and Labor, U.S. House of Representatives. March 16, 2010 [cited 2012 Feb 20] Available from: URL: http://www.osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_table=TESTIMONIES&p_id=1062.

- 10.Lashuay N, Harrison R. Barriers to occupational health services for low-wage workers in California. San Francisco: Commission on Health and Safety and Workers' Compensation, California Department of Industrial Relations; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teran S, Baker R, Sum J. Report and recommendations of the California Working Immigrant Safety and Health Coalition. Berkeley (CA): University of California, Berkeley, Labor Occupational Health Program; 2002. Improving health and safety conditions for California's immigrant workers. [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Employment Law Project. Winning wage justice: a summary of research on wage and hour violations in the United States. 2012 [cited 2012 Feb 20] Available from: URL: http://nelp.3cdn.net/509a6e8a1b8f2a64f0_y2m6bhlf6.pdf.

- 13.Bernhardt A, Milkman R, Theodore N, Heckathorn D, Auer M, DeFilippis J, et al. Broken laws, unprotected workers: violations of employment and labor laws in America's cities. Chicago, New York, Los Angeles: University of Illinois at Chicago, Center for Urban Economic Development; National Employment Law Project; University of California; 2009. Los Angeles, Institute for Research on Labor and Employment. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murray LR. Sick and tired of being sick and tired: scientific evidence, methods, and research implications for racial and ethnic disparities in occupational health. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:221–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Restaurant Opportunities Center of New York; New York City Restaurant Industry Coalition. The great service divide: occupational segregation and inequality in the New York City restaurant industry. New York: ROC-NY and New York City Restaurant Industry Coalition; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Restaurant Opportunities Center United. Behind the kitchen door: a multi-site study of the restaurant industry. New York: ROC-United; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Federation of Labor—Congress of Industrial Organizations. 20th ed. Washington: AFL-CIO; 2011. Death on the job: the toll of neglect. A national and state-by-state profile of worker safety and health in the United States. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernhardt A, McGrath S. Trends in wage and hour enforcement by the U.S. Department of Labor, 1975–2004. New York: New York University School of Law, Brennan Center for Justice; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmitt J. Labor markets and economic inequality in the United States since the end of the 1970s. Int J Health Serv. 2005;35:655–73. doi: 10.2190/742C-NWPQ-N7RD-3H9V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weil D. Improving workplace conditions through strategic enforcement: a report to the wage and hour division. Boston: Boston University; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weil D, Pyles A. Why complain? Complaints, compliance, and the problem of enforcement in the U.S. workplace. Comp Labor Law Policy J. 2005;27:59–92. [Google Scholar]

- 22. H.R. 1409 (11th) (2009 Mar 10) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gould E, Shierholz H. Economic Policy Institute briefing paper no. 299. Washington: EPI; 2011. The compensation penalty of “right-to-work” laws. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guyett S. Indiana becomes 23rd “right-to-work” state. Reuters Newservice. 2012 Feb 1; [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holmes TJ. The effect of state policies on the location of manufacturing: evidence from state borders. J Polit Econ. 1998;106:667–705. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lafer G. Economic Policy Institute memorandum no. 174. Washington: EPI; 2011. What's wrong with “right-to-work”: Chamber's numbers don't add up. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore WJ, Newman RJ. The effects of right-to-work laws: a review of the literature. Ind Lab Rel Rev. 1985;38:571–85. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loomis D, Schulman MD, Bailer AJ, Stainback K, Wheeler M, Richardson DB, et al. Political economy of U.S. states and rates of fatal occupational injury. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:1400–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.131409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bernhardt A, Boushey H, Dresser L, Tilly C, editors. Confronting the gloves-off economy: America's broken labor standards and how to fix them. Champaign (IL): Labor and Employment Relations Association; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaplan E. Hilda Solis: labor's new sheriff. The Nation. 2010 Apr 12; [Google Scholar]

- 31.Department of Labor (US) US Labor Department announces comprehensive final rule on H-2B foreign labor certification program [press release] 2012 Feb 10 [cited 2013 Jul 5] Available from: URL: http://www.dol.gov/opa/media/press/eta/eta20120283.htm.

- 32.Sturgeon J, Poo A-J. Fair pay for 2.5 million home care aides facing industry opposition. New American Media. 2012 Feb 16; [Google Scholar]

- 33.Department of Labor (US) Data enforcement database [cited 2012 Feb 20] Available from: URL: http://ogesdw.dol.gov/index.php.

- 34.Department of Labor (US) US Labor Department, California sign agreement to reduce misclassification of employees as independent contractors [press release] 2012 Feb 9 [cited 2013 Jul 5] Available from: URL: http://www.dol.gov/opa/media/press/whd/WHD20120257.htm.

- 35.Department of Labor (US) FY 2013 Department of Labor budget in brief. Washington: Department of Labor (US); 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chinese Progressive Association. Check, please! Health and working conditions in San Francisco Chinatown restaurants. San Francisco: CPA; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 37.San Francisco Health Code. Art. 8, §440.2. Permit procedures (1968) [Google Scholar]

- 38.California Labor Code, Division 4, Part 1, Chapters 3-4. Conditions of compensation liability and compensation insurance and security [cited 2012 Feb 20] Available from: URL: http://www.leginfo.ca.gov/cgi-bin/calawquery?codesection=lab&codebody=

- 39.Dembe AE, Harrison RJ. Access to medical care for work-related injuries and illnesses: why comprehensive insurance coverage is not enough to assure timely and appropriate care [cited 2012 Feb 20] Available from: URL: http://www.dir.ca.gov/chswc/caresearchcolloquium/p9/allard%20dembe%20rpt.pdf.

- 40.New York City Council, Committee on Health. Hearing transcript 3/31/08 for Int. 0569-2007 [cited 2012 Feb 20] Available from: URL: http://legistar.council.nyc.gov/LegislationDetail.aspx?ID=451330&GUID=A90C8C12-5590-49C0-8672-FC97812EA690&Options=&Search=

- 41.New York City Council, Committee on Health. Meeting minutes 3/31/08 for Int. 0569-2007 [cited 2012 Feb 20] Available from: URL: http://legistar.council.nyc.gov/LegislationDetail.aspx?ID=451330&GUID=A90C8C12-5590-49C0-8672-FC97812EA690&Options=&Search=

- 42.Viscusi WK. The impact of occupational safety and health regulation. Bell J Econ. 1979;10:117–40. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gray WB, Scholz JT. Does regulatory enforcement work? A panel analysis of OSHA enforcement. Law Soc Rev. 1993;27:177–213. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mendeloff J, Gray WB. Inside the black box: how do OSHA inspections lead to reductions in workplace injuries? Law Policy. 2005;27:219–37. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Department of Health and Human Services (US), Office of the Surgeon General. National Prevention Strategy [cited 2012 Feb 20] Available from: URL: http://www.healthcare.gov/prevention/nphpphc/strategy/index.html.

- 46.The White House (US) Middle class task force announces agency partnerships to build a strong middle class through a green economy [press release]; 2009 May 26 [cited 2012 Feb 20] Available from: URL: http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/middle-class-task-force-announces-agency-partnerships-build-a-strong-middle-class-t.

- 47.State of California, Department of Industrial Relations. Labor Enforcement Task Force [cited 2012 Feb 20] Available from: URL: http://www.dir.ca.gov/letf/letf.html.

- 48.New York State, Department of Labor. Employer misclassification of workers [cited 2012 Feb 20] Available from: URL: http://www.labor.ny.gov/ui/employerinfo/employer-misclassification-of-workers.shtm.

- 49.Interagency Task Force on Employee Misclassification. Report to Governor Jennifer M. Granholm. 2008 Jul 1 [cited 2012 Feb 20] Available from: URL: http://www.michigan.gov/documents/dleg/R08 _07_01Rrt_to_the_Gov_240789_7.pdf.

- 50.National Council for Occupational Safety and Health. Local COSH groups [cited 2012 Feb 20] Available from: URL: http://www.coshnetwork.org/COSHGroupsList.

- 51.State of California, Employment Development Department. Underground economy operations [cited 2012 Feb 20] Available from: URL: http://www.edd.ca.gov/payroll_taxes/Underground _Economy_Operations.htm.

- 52.Department of Labor (US) Washington: Government Accountability Office (US); 2009. Wage and Hour Division's complaint intake and investigative processes leave low-wage workers vulnerable to wage theft. Testimony of Gregory D. Kutz, Managing Director, Forensic Audits and Special Investigations, and Jonathan T. Meyer, Assistant Director, Forensic Audits and Special Investigations, before the Committee on Education and Labor, U.S. House of Representatives. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zabin C, Dube A, Jacobs K. The hidden public costs of low-wage jobs in California. State California Labor. 2004;4:3–44. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wegman DH, Liverman CT, Schultz AM, Strawbridge LM Committee on Occupational Information and Electronic Health Records. Incorporating occupational information in electronic health records: letter report. Washington: National Academies Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US), The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. NIOSH program portfolio: occupational health disparities. Activities: NIOSH funded research grants [cited 2012 Feb 16] Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/programs/ohd/grants.html.

- 56.Gaydos M, Bhatia R, Morales A, Lee PT, Liu SS, Chang C, et al. Promoting health and safety in San Francisco's Chinatown restaurants: findings and lessons learned from a pilot observational checklist. Public Health Rep. 2011;126(Suppl 3):62–9. doi: 10.1177/00333549111260S311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Simon PA, Leslie P, Run G, Jin GZ, Reporter R, Aguirre A, et al. Impact of restaurant hygiene grade cards on foodborne-disease hospitalizations in Los Angeles County. J Environ Health. 2005;67:32–6. 56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fielding JE, Aguirre A, Palaiologos E. Effectiveness of altered incentives in a food safety inspection program. Prev Med. 2001;32:239–44. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jin GZ, Leslie P. The effect of information on product quality: evidence from restaurant hygiene grade cards. Quart J Econ. 2003;118:409–51. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cohen DA, Bhatia R. Nutrition standards for away-from-home foods in the USA. Obes Rev. 2012;13:618–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2012.00983.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Restaurant Opportunities Center United. ROC National diners' guide 2012: a consumer guide on the working conditions of American restaurants. New York: ROC-United; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cook WK, Heller J, Bhatia R, Farhang L. A health impact assessment of the Healthy Families Act of 2009. Oakland (CA): Human Impact Partners and San Francisco Department of Public Health; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bhatia R, Corburn J. Lessons from San Francisco: health impact assessments have advanced political conditions for improving population health. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:2410–8. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]