Abstract

Localities Embracing and Accepting Diversity (LEAD) is an ongoing place-based pilot program aimed at improving health outcomes among Aboriginal and migrant communities through increased social and economic participation. Specifically, LEAD works with mainstream organizations to prevent race-based discrimination from occurring. The partnership model of LEAD was designed to create a community intervention that was evidence-based, effective, and flexible enough to respond to local contexts and needs.

LEAD's complex organizational and partnership model, in combination with an innovative approach to reducing race-based discrimination, has necessitated the use of new language and communication strategies to build genuinely collaborative partnerships. Allocating sufficient time to develop strategies aligned with this new way of doing business has been critical. However, preliminary data indicate that a varied set of partners has been integral to supporting the widespread influence of the emerging LEAD findings across partner networks in a number of different sectors.

There is a strong link between self-reported discrimination and poorer health.1 In addition, social conditions that promote cultural diversity have been found to promote good health.2 Promoting diversity and reducing discrimination are also important for building productive, socially cohesive, and inclusive communities, and for protecting human rights.3

Aboriginal Australians suffer from high rates of unemployment and incarceration, low income, and a high burden of ill health and mortality, including a shorter life expectancy (9–12 years fewer) than other Australians.4 Although not as stark, health disparities also affect migrant communities in Australia,5,6 with the health of immigrants generally declining with duration of residence in Australia in comparison with their post-arrival status, even after accounting for the effects of age.7,8

The overall objectives of the Localities Embracing and Accepting Diversity (LEAD) program are to improve health and reduce anxiety and depression among Aboriginal and migrant communities through increased social and economic participation, specifically by working with mainstream organizations to prevent race-based discrimination from occurring and to promote the benefits of cultural diversity.

There is mounting evidence that an area's social environment is important in determining its area-based variability in health9–13 and that place-based interventions may be effective methods of addressing health disparities and social determinants of health. LEAD is being implemented as a place-based pilot in partnership with local councils. In this article, “councils” refers to local governing bodies, and the areas governed by councils are local government areas (LGAs).

The partnership model of LEAD was designed to create a community intervention that was evidence-based, effective, and flexible enough to respond to local contexts and needs. Two local councils serve as the primary implementing partners, conducting LEAD activities in their LGAs in partnership with organizations in educational, employment, and retail settings. These settings have been identified as places where discrimination is common and likely to harm health in affected populations, and where considerable potential for prevention is possible. Councils are supported in their role through partnership with the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation (VicHealth) as the primary LEAD funding body; the Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission (VEOHRC); beyondblue, Australia's “peak body” (i.e., an association or group for an industry or area of common interest) for mental health issues; the Municipal Association of Victoria (MAV), the peak body for councils in the state of Victoria; the University of Melbourne; and the Department of Immigration and Citizenship.

In addition to being based on a complex organizational and partnership model, LEAD represents an innovative approach to reducing race-based discrimination. The design of the LEAD program is underpinned by VicHealth's 2009 report, “Building on Our Strengths: A Framework to Reduce Race-Based Discrimination and Support Diversity in Victoria.”3 The framework is primarily focused on addressing the conditions that are contributing to interpersonal and systemic discrimination by working with mainstream organizations to develop pro-diversity organizational environments throughout individual LGAs, rather than attempting to ameliorate the effects of racism after it has occurred.

LEAD is now in the second year of the implementation phase, which is expected to run until December 2013. The findings presented in this article are, therefore, preliminary, as LEAD is ongoing; thus, evaluation of the program's success is not part of this article's scope.

GOVERNANCE AND PARTNERSHIP MODEL

LEAD is a partnership among VicHealth, the primary funding body, and other government agencies, as well as academic, policy, and community experts. The LEAD program is governed by two groups—the LEAD Advisory Group, comprising senior representatives from each of the partner and funding agencies, and the LEAD Operational Group, comprising representatives from VicHealth, VEOHRC, MAV, the University of Melbourne LEAD evaluation team, and the two LEAD local council sites. The purpose of the LEAD Advisory Group is to provide an opportunity for the partner and funding agencies, councilors from the implementing councils, and Aboriginal and culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) community groups to guide the program design. The LEAD Operational Group was convened to ensure networking and information exchange between organizations directly involved in program implementation and evaluation.

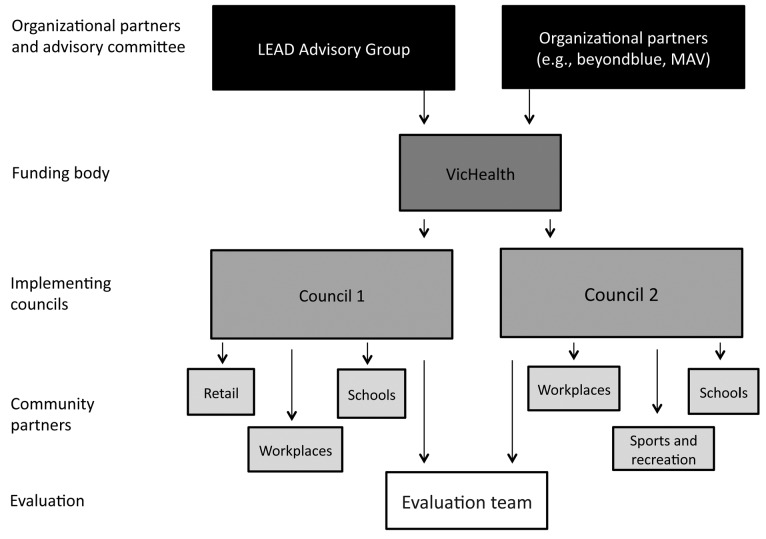

The LEAD partnership model moves away from a model in which funding bodies require implementing organizations to apply for funding based on preset specifications. In contrast, the basis of the LEAD partnership model is that VicHealth, as the primary funding body, works directly with the implementing councils to develop a set of strategies that integrates consistency across two sites with responsiveness to local contexts. VicHealth is also responsible for managing the evaluation contract with the University of -Melbourne -evaluation team, as well as the coordination of dissemination activities through partner agencies, including MAV and beyondblue, and the evaluation team. The councils' role within the program is to develop locally appropriate strategies based on the best available evidence3 in partnership with local community organizations, such as Aboriginal and CALD peak body representative groups, schools, workplaces, and retail settings. The aims of the LEAD partnership model are to draw on the strengths of respective partners and respond to a range of local contexts while being informed by current evidence and best practices.3 Through this partnership model (Figure), the councils have benefited from the input of a wide network of agencies and organizations to strengthen implementation design and resource dissemination.

Figure.

Partnership and program governance model: LEAD place-based pilot program to reduce race-based discrimination and improve the health of Aboriginal and migrant communities, Victoria, Australia

LEAD = Localities Embracing and Accepting Diversity

MAV = Municipal Association of Victoria

VicHealth = Victorian Health Promotion Foundation

VicHealth developed the LEAD program to be implemented through local councils on the basis that local government generally has a strong track record in promoting diversity and addressing discrimination.14–16 In addition to being implementation partners, local councils are ideal LEAD intervention settings, as they are responsible for a range of areas in which discrimination may occur and within which there is potential to develop pro-diversity organizational environments. Councils are, therefore, in a unique position to facilitate a coordinated approach across these settings, enhanced by an understanding and ability to respond to local issues. While LEAD implementation within councils mainly focused on the organization as an employer rather than a service provider, it set a base for expansion of antiracist strategies and processes into other settings managed by local government. The two LEAD councils were selected partly because of their demonstrated history in working to support diversity and address disadvantage affecting people from Aboriginal and migrant backgrounds.

The combination of a complex partnership model and a new strategy for addressing discrimination has accentuated the need present in all community interventions for effective communication, sufficient time and resources to ensure genuine collaboration, and clear partner roles, including for the funding and advisory bodies, evaluation team, and implementing councils. All LEAD partners contributed to clarifying appropriate roles by developing communication and dissemination protocols, particularly to establish agreement around issues such as data access, intellectual property, and branding of LEAD materials. These agreements have also been integral to ensuring that the particular needs of each partner organization are accommodated, including LEAD's fit with their core organizational aims.

A varied set of partners has been integral in increasing the program's reach and promoting findings. For example, the MAV is well positioned to ensure the dissemination of LEAD findings to councils in the state of Victoria, as well as promote the findings of LEAD more widely in government policy and planning. The contribution of beyondblue supports a focus on the relationship between race-based discrimination and mental health in policy development.

COMMUNITY PARTNERSHIPS

While LEAD program intervention strategies are primarily focused on mainstream community organizations, migrant and Aboriginal communities within implementing councils are primary stakeholders in LEAD activities.3 LEAD councils and the evaluation team consulted affected communities regarding program structure and development, with the governance of LEAD evaluation data led by the communities. This process was also important in building and strengthening ties between these communities and their local councils.

A basic tenet of the LEAD program is the integration of flexible strategies utilizing local knowledge to respond to organizational needs and community concerns. This approach is underpinned by ecological theory, which suggests that interventions focusing on different structural levels may reinforce individual behavior and attitudinal change.17–19 Within the LEAD councils, there is, therefore, a mixture of intervention activities and strategies, with some elements of LEAD being consistent across the two sites while other elements vary.

Organizational audits and pro-diversity training have been used across LEAD. The evaluation team, in consultation with VicHealth and the LEAD councils, developed retail, workplace, and educational audit tools as part of LEAD to allow organizations to independently assess their policies and processes against best-practice examples. These tools will be packaged and made widely available through partners such as the MAV, which facilitates council-to-council knowledge exchange, through dissemination activities undertaken by the evaluation team, and through the organizational and policy-making networks of VicHealth.

The pro-diversity training package was also developed specifically for LEAD. As an organizational partner of LEAD, VEOHRC was well placed to design a training package that complemented the program's underlying principles. To this end, VEOHRC designed the training package to enable pro-diversity change at both individual and organizational levels while being flexible enough to respond to organizational contexts.

Implementation activities specific to councils have included supplemental cultural competency training, individualized student workshops and activities, and organizational initiatives, such as diversity lunches and team-building activities. Central to LEAD implementation was ensuring that strategies had the support of champions in relevant organizations to ensure wider organizational program ownership.3 Engaging mainstream community organizations to address race-based discrimination, rather than working with affected communities directly, was an unfamiliar approach for prospective partners, which required a new way of thinking about antiracism strategies. Champions helped orient local organizations to the program's conceptual underpinnings.

Educational settings

Each implementing council approached a mix of local primary and secondary schools. While some schools were approached due to a strong prior track record in developing pro-diversity environments, other schools became involved in LEAD due to concerns about racial tensions within the school and hoped that involvement in LEAD would address these issues. There was also significant variation in racial/ethnic diversity among LEAD schools. Each of these factors affected schools' motives for being involved with LEAD as well as the resources and time they could commit to developing a partnership with a council and implementing LEAD strategies.

School staff were generally supportive of programs to address race-based discrimination, but they also experienced significant time pressures and had -limited resources to expend on an additional program, especially one that was not always considered to be related to a core function of schools. Where schools were interested in being involved, there was often less interest in and fewer resources dedicated to enabling organizational changes, rather than discrete, one-off activities. While neither local council had strong ties with the schools before LEAD, the program has been successful in strengthening partnerships between councils and local schools, as well as among schools. As part of the program, nine schools have received pro-diversity training across the two LGAs, and the councils have worked with six schools to complete the educational audit tool. Two local schools, in conjunction with one of the local councils, have partnered to develop a combined Cultural Day to celebrate the schools' cultural and ethnic diversity. School-council partnerships have also highlighted areas where schools feel they could be better supported, such as in the provision of educational resources. One of the LEAD councils in particular has met this need through facilitating partnership formation between schools and other local organizations.

Employment and retail settings

Employment and retail settings were varied in terms of sectors, organizational size, and racial/ethnic composition. Retail settings were primarily focused on interactions between staff and the public, while employment settings were primarily concerned with internal employee interactions. While all organizations struggled with time pressures, employment settings were motivated to participate in LEAD through the appeal of a harmonious and, therefore, more productive work staff, as well as the potential to attract new customers and ensure high-quality customer service. Employers were also cognizant of the need to be compliant with equal opportunity legislation20 and saw LEAD as a vehicle to achieve this compliance, which has led to employees in five organizations undergoing training.

However, management staff within retail settings often did not view addressing race-based discrimination as part of the organization's core business in relation to either employees or customers. Within the retail setting, high employee turnover often disrupted LEAD development and implementation, which was particularly discouraging for LEAD staff members when they had already made progress in establishing a partnership with an individual manager who was subsequently replaced by someone who was no longer willing to be involved in the LEAD program.

A recurring barrier to implementing LEAD within local branches of large companies was the limited scope available to carry out changes without approval from head offices, which were sometimes national or international in scale. However, the networks within companies also facilitated the dissemination of successful strategies. In particular, one retailer with a branch participating in LEAD has used program resources and strategies in offices across Australia.

Councils

Within councils, partnership development was mainly focused on collaboration with key departments and people, including senior management and human resources (HR). LEAD staff sought to embed approaches in council governance and operations with the aim of ensuring commitment from the whole council and long-term sustainability. Developing the understanding and backing of senior management was considered crucial for implementing strategies within councils, as having endorsement at higher levels would lend authority to organizational change undertaken through LEAD.3 Engagement of the HR department was vital, given that many strategies focused on process and policy changes.

The council setting itself has been quite successful in implementing LEAD strategies and effecting organizational change. This success has primarily been due to a dedicated, funded position within the organization to drive various strategies, as well as strong internal support from upper-level management. A key outcome to date is the adoption of an Aboriginal Employment Strategy, embedded as part of a larger pro-diversity action plan that was initiated as a result of the organizational audit within one of the councils. The Aboriginal Employment Strategy is a five-year plan that aims to increase the proportion and retention of Aboriginal people employed at council and to achieve positive outcomes for these employees by developing an inclusive and welcoming workplace. While the majority of LEAD implementation within the council setting has focused on the council as an employer rather than a service provider, there have been some recent attempts to expand implementation into areas that councils manage, such as recreational centers. In addition, multiple Victorian councils have initiated antiracism interventions in their areas based on the LEAD program or expressed interest in incorporating elements of LEAD into their LGAs. These efforts indicate a high level of receptivity among Victorian councils to programs such as LEAD, which bodes well for future dissemination of LEAD findings once the program and evaluation have been finalized.

DISCUSSION

Due to concern from both funding and implementing organizations about the sustainability of successful programs at the conclusion of funding cycles21 and an increased interest in understanding change processes within community settings,22,23 development of community partnerships has become a key strategy in public health interventions as a means of translating relevant findings into policy and practice.24

A particular dilemma in collaborative research is defining roles between the funding body and implementing partners in a way that supports implementers through resources, networks, and technical expertise while maintaining both autonomy and accountability.25 This combination of financial support and collaborative program design is an increasingly common way of funding community interventions.26 As the LEAD program demonstrates, despite the additional planning and development time required by a complex multilevel partnership model, having partners in various settings contributes to the program's reach and sustainability. This reach occurs through dissemination and knowledge exchange across a variety of networks, leading to deeper embedding of findings in relevant policy and practice.27

The LEAD partnership model continues to effectively garner support from community partners to work with mainstream community organizations in preventing discrimination, rather than directly helping affected communities deal with racism. However, getting to this point often took considerable time and effort, both in crafting the message for presentation to partners and for the partners to adopt this new way of thinking. Despite supporting the aims of the LEAD program in principle, many organizations in educational and retail settings did not view the program as relevant to their core business. This disconnect may indicate that greater investment is required to identify valued areas of benefit associated with pro-diversity policies and environments in these settings. Alternatively, pro-diversity strategies may need to be implemented at other levels. For example, program implementation could happen through the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, which may be better placed than local councils to enable organizational development in schools. Similarly, pro-diversity strategies may be better implemented from central offices of large companies, which maintain much more control than local branches over HR policies and promotional materials. However, where branches have been successful in implementing pro-diversity strategies, there is significant potential for other branches within the company to adopt these strategies either centrally through the head office or through peripheral branch-to-branch networks.

Working at alternative levels may also address the issue of staff turnover experienced in retail, employment, and, to some extent, school settings. Specifically, advocating champions was important in lending authority to implementation strategies, but reliance on this strategy could also be a drawback when these individuals leave an organization. Working with champions to engage policy makers at higher organizational levels may reinforce the role of champions while minimizing dependency on specific individuals.

CONCLUSIONS

LEAD is a place-based pilot program that aims to address race-based discrimination to improve the health of affected Aboriginal and CALD communities. Although LEAD partnership formation has been time intensive due to a complex program model and novel approach to addressing race-based discrimination, the model has been successful in engaging community organizations to initiate pro-diversity change in their environments. LEAD partnerships have also enabled program findings and resources to be communicated and implemented across partner networks in a number of different sectors. LEAD resources and strategies used in one retail branch participating in the program have been used by associated businesses in several other Australian states, and the distribution of organizational resources such as audit tools has occurred across a range of localities within Victoria. More developments will occur once the LEAD pilot program and its evaluation have concluded and the results are more widely shared with other local governments. These examples highlight the importance of effective partnership development in enhancing the sustainability of community interventions and embedding relevant program findings into practice.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the LEAD partners for their support throughout the evaluation of LEAD, and Peter Streker and Pamela Rodriguez from VicHealth for their support in compiling this article. Ethical approval to conduct the LEAD evaluation was received from the Melbourne University Health Sciences Human Ethics Sub-Committee on January 27, 2010.

Footnotes

The Localities Embracing and Accepting Diversity (LEAD) program is a joint partnership among the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation (VicHealth), the Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission, beyondbue, the Municipal Association of Victoria, the Department of Immigration and Citizenship (through its Diverse Australia program), and the two implementing LEAD councils.

REFERENCES

- 1.Paradies Y. A systematic review of empirical research on self-reported racism and health. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35:888–901. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Victorian Health Promotion Foundation. Melbourne (Victoria): Victorian Health Promotion Foundation; 2007. More than tolerance: embracing diversity for health. Discrimination affecting migrant and refugee communities in Victoria, its health consequences, community attitudes and solutions: a summary report. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paradies Y, Chandrakumar L, Klocker N, Frere M, Webster K, Burrell M, et al. Melbourne (Victoria): Victorian Health Promotion Foundation; 2009. Building on our strengths: a framework to reduce race-based discrimination and support diversity in Victoria. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision. Canberra (Australia): Productivity Commission; 2009. [cited 2012 May 8]. Overcoming indigenous disadvantage: key indicators 2009. Also available from: URL: http://www.pc.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/90129/key-indicators-2009.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Australian Bureau of Statistics. National health survey: mental health. 2001. [cited 2012 May 8]. Available from: URL: http://www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/ausstats/subscriber.nsf/0/E7621A9758D3A4B 5CA256DF1007C0637/$File/48110_2001.pdf.

- 6.Anikeeva O, Bi P, Hiller JE, Ryan P, Roder D, Han GS. The health status of migrants in Australia: a review. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2010;22:159–93. doi: 10.1177/1010539509358193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khoo SE. Health and humanitarian migrants' economic participation. J Immigr Minor Health. 2010;12:327–39. doi: 10.1007/s10903-007-9098-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiswick BR, Lee YL, Miller PW. Immigrant selection systems and immigrant health. Contemp Econ Policy. 2008;26:555–78. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaix B, Rosvall M, Merlo J. Neighborhood socioeconomic deprivation and residential instability: effects on incidence of ischemic heart disease and survival after myocardial infarction. Epidemiology. 2007;18:104–11. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000249573.22856.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chandola T. The fear of crime and area differences in health. Health Place. 2001;7:105–16. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8292(01)00002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindström M, Merlo J, Ostergren PO. Social capital and sense of insecurity in the neighbourhood: a population-based multilevel analysis in Malmö, Sweden. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56:1111–20. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00114-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lochner KA, Kawachi I, Brennan RT, Buka SL. Social capital and neighborhood mortality rates in Chicago. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56:1797–805. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00177-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phongsavan P, Chey T, Bauman A, Brooks R, Silove D. Social capital, socio-economic status and psychological distress among Australian adults. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:2546–61. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hussain A, Ishaq M. Managing race equality in Scottish local councils in the aftermath of the Race Relations (Amendment) Act 2000. Int J Public Sector Manag. 2008;21:586–610. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nishishiba M. Portland (OR): Portland State University; 2003. Assessing the impact of a diversity initiative in local government. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Department for Communities and Local Government (UK) Guidance for local authorities on community cohesion contingency planning and tension monitoring. London: Department for Communities and Local Government (UK); 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKown C. Applying ecological theory to advance the science and practice of school-based prejudice reduction interventions. Educ Psychol. 2005;40:177–89. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trickett EJ. Multilevel community-based culturally situated interventions and community impact: an ecological perspective. Am J Community Psychol. 2009;43:257–66. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9227-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. 1988;15:351–77. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parliament of Victoria. Equal Opportunity Act 2010. [cited 2012 May 8]. Available from: URL: http://www.legislation.vic.gov.au/Domino/Web_Notes/LDMS/PubStatbook.nsf/51dea49770555ea 6ca256da4001b90cd/7CAFB78A7EE91429CA25771200123812/$FILE/10-016a.pdf.

- 21.Hawe P, Riley T, Ghali L. Developing sustainable interventions: theory and evidence. In: Herrman H, Saxena S, Moodie R, editors. Promoting mental health: concepts, emerging evidence, practice. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. pp. 54–5. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schensul JJ. Sustainability in HIV prevention research. In: Trickett EJ, Pequegnat W, editors. Community interventions and AIDS. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. pp. 176–95. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trickett EJ, Espino SR, Hawe P. How are community interventions conceptualized and conducted? An analysis of published accounts. J Community Psychol. 2011;39:576–91. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Best A, Stokols D, Green LW, Leischow S, Holmes B, Buchholz K. An integrative framework for community partnering to translate theory into effective health promotion strategy. Am J Health Promot. 2003;18:168–76. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-18.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Minkler M, Blackwell AG, Thompson M, Tamir H. Community-based participatory research: implications for public health funding. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1210–3. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.8.1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weiss ES, Anderson RM, Lasker RD. Making the most of collaboration: exploring the relationship between partnership synergy and partnership functioning. Health Educ Behav. 2002;29:683–98. doi: 10.1177/109019802237938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lasker RD, Weiss ES, Miller R. Partnership synergy: a practical framework for studying and strengthening the collaborative advantage. Milbank Q. 2001;79:179–205. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]