Abstract

Because they focus on culturally and contextually specific health determinants, participatory approaches are well-recognized strategies to reduce health disparities. Yet, few models exist that use academic and community members equally in the grant funding process for programs aimed at reducing and eliminating these disparities. In 2008, the Communities IMPACT Diabetes Center in East Harlem, New York, developed a partnered process to award grants to community groups that target the social determinants of diabetes-related disparities. Community and academic representatives developed a novel strategy to solicit and review grants. This approach fostered equality in decision-making and sparked innovative mechanisms to award $500,000 in small grants. An evaluation of this process revealed that most reviewers perceived the review process to be fair; were able to voice their perspectives (and those perspectives were both listened to and respected); and felt that being reviewers made them better grant writers. Community-academic partnerships can capitalize on each group's strengths and knowledge base to increase the community's capacity to write and review grants for programs that reduce health disparities, providing a local context for addressing the social determinants of health.

Social determinants of health (SDH) are economic, social, and political conditions that influence individual and group differences in health status.1 SDH include characteristics of neighborhoods, social policies, and living and working conditions that contribute to health disparities that cannot be explained by individual factors such as genetics or personality traits alone. Community-based participatory approaches (CBPA) to health promotion can help reduce health disparities by focusing on locally defined priorities and locally specific health determinants.2–5 In contrast, research activities that do not take local priorities and perspectives into account may generate inappropriate strategies and recommendations that fail to address relevant SDH.

Research stemming from CBPA is enhanced through long-term commitments to co-learning, research capacity building, and generating findings that can benefit all partners.3–5 CBPA are gaining acceptance, but such approaches are sometimes equated with qualitative research and needs assessments and, thus, are considered less rigorous than traditional research.2,6 More recently, CBPA have informed other types of research, such as interventions.6,7 However, community input into grant-making has remained inadequate. Such input may be important so that communities can introduce novel approaches and solutions to address the SDH that lead to disparities by developing research priority areas and enhancing the pipeline of community experts to review and write grants. While some grant review processes have engaged their communities,8,9 to our knowledge, there are no published examples of egalitarian community-academic partnership models that make a commitment to community engagement and that bring a bona fide community voice to the health disparities grant funding process.

In 2007, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funded 18 Centers of Excellence to Eliminate Disparities to advance evidence-based programs to eliminate racial/ethnic health disparities through its Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health (REACH) U.S. initiative. These Centers were, in part, charged with using homegrown methods for selecting, funding, and supporting one-year $25,000–$50,000 legacy grants to community organizations to initiate or enhance work consistent with each Center's focus.

One such Center is the Communities IMPACT Diabetes Center (hereafter, IMPACT) in the East Harlem neighborhood of New York City. IMPACT was spearheaded by Mount Sinai School of Medicine and comprises a task force of researchers from Mount Sinai and other local academic institutions, clinicians, community residents, and representatives from community-based organizations based mainly in East Harlem and surrounding neighborhoods who united to understand and address community needs to improve diabetes prevention and control. Through these legacy grants, IMPACT aimed to support and fund innovative projects that address the social determinants of diabetes among African American and Latino populations. Given that CBPA are a pillar of IMPACT, it seemed appropriate to extend the application of CBPA to the grant selection process. Thus, we aimed to work with community members to select grants as a way to improve the community capacity to apply for and review grants.

METHODS

Development of a grant funding process

During IMPACT's first year, in 2008, we formed a legacy grant subcommittee to solicit, fund, and oversee grants to community organizations to address disparities in diabetes prevention and control. We selected two community representatives and one community-based investigator to cochair the subcommittee, establishing from the outset that community input would be critical and valued in the grant selection process. The subcommittee identified the need to build local capacity to write a request for proposal (RFP), as well as to review and write grants, and the subcommittee developed workshops and webinars to meet these needs. This effort was imperative, as one of IMPACT's aims was to develop a cadre of trained grant reviewers who would ultimately be able to review community-engaged and health disparities research proposals at regional and national levels.

Next, we developed an RFP, scoring criteria, and a decision-making process. Academic representatives suggested benchmarking the scoring criteria by including some federal review criteria (i.e., significance, innovation, quality of the team, evaluation, and robust budget justification). Community members contributed criteria that focused on organizations genuinely being a part of and serving their community and on the potential impact of the proposed program on the target population, with an emphasis on ensuring that proposals being considered had integrity and were not exaggerated or inaccurately portrayed through polished grant writing (i.e., the criteria ensured that an in-person visit would reveal any exaggerations of the written proposal). The subcommittee decided to score proposals using a scale of 0–4 points for each criterion (where 0 = “does not meet requirement” and 4 = “exceeds requirement”). Some sections (e.g., project description and program evaluation) were weighted more heavily than others (e.g., organizational background), and the total possible score was 100 points. The subcommittee then disseminated the RFP form through local and regional partners and listservs. In each year, we expanded the geographic range for grants: we began locally in East Harlem in 2008 during cycle 1; as our expertise grew, we expanded to New York State, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania in 2009 and 2010 during cycles 2 and 3, and then to the Northeastern states from Maine to Maryland in 2011 and 2012 during cycles 4 and 5.

Formation of a grant review committee and the grant review process

We invited members of the entire IMPACT Task Force to become grant reviewers. Those who agreed participated in a mandatory training session led by IMPACT staff to become familiar with the scoring criteria and learn more about proposal evaluation. Previous experience in grant writing or reviewing was not a requirement. Community members who served as grant reviewers received a stipend.

Every proposal underwent technical review by IMPACT staff (stage 1) before being randomly assigned for review to one community and one academic representative. Reviewers each independently scored two to three proposals, on average, and sent them to IMPACT staff for tabulation (stage 2). The seven to 10 highest-scoring proposals moved forward to a full committee review (stage 3). The rest of the grants were not discussed unless a reviewer objected. Adopting a format similar to that used by the National Institutes of Health, IMPACT had primary reviewers present their assigned proposal to the full committee. In addition, during this meeting, all reviewers received a copy of the abstract, evaluation plan, and budget of each proposal discussed. They asked questions of the primary reviewers, made comments, and then voted individually in favor of or against each grant proposal. By the end of that first full committee meeting, the reviewers had chosen four to six finalists. Within the next two weeks, primary reviewers had a conference call with the finalists to answer questions and discuss concerns that arose from the first full committee meeting (stage 4). Once all conference calls were completed, the full committee reconvened. Primary reviewers shared information they gathered from the calls, and the full committee voted and selected organizations for funding (stage 5).

Once grantees were selected and funded, they were required to submit progress reports to and participate in conference calls with IMPACT staff on a regular basis to track progress and discuss and address needs. Community members refined the monitoring process based on the difficulties that some early grassroots organizations had in meeting their objectives. We also partnered with other REACH U.S. grantees to host two annual health disparities summits, which brought together legacy grantees for a two-day technical assistance and networking conference.

The grant review process evolved over time, based on qualitative and quantitative feedback from the group and debriefing meetings. First, the second stage of gathering more information from finalists changed from a telephone call to a site visit. One community representative cochair expressed a mistrust of written applications as the sole basis for selection. The subcommittee agreed that paying a visit to the applicant organization would bring forth new strengths and weaknesses; allow us to offer technical assistance, even to those sites that would not be funded; and help us build relationships with those who would be funded, so we could better provide guidance and support. Pairs of community and academic reviewers would visit each finalist organization to tour their site, meet with key leaders, pose questions that arose during the stage 1 review, and offer suggestions to improve the work proposed. At the conclusion of these visits, the pair jointly completed a site visit evaluation form and presented their findings to the full review committee during stage 3.

Second, partners developed a system for dealing with reviewer scoring discrepancies. The legacy grant subcommittee decided that scores that differed by 20 points or more (out of the total 100 points) would prompt the two reviewers meeting to discuss the proposal prior to the first full grant review meeting and have an opportunity to rescore the proposal. If major score differences remained, the application was presented to the entire grant review committee.

Third, we improved our quality of scoring and came up with a more sophisticated scoring and voting system. In cycle 1, some reviewers found the scoring schema to be somewhat unclear; thus, for subsequent cycles, they suggested a scoring system based on grades (where 0 = “F/Absent from proposal” and 4 = “A/Excellent”). Similarly, during the full committee meetings in cycles 2–5, instead of voting “yea” or “nay” on a grant, reviewers voted using this same letter/points system.

Surveys

Following cycles 2–4, we created and e-mailed an anonymous electronic survey to all reviewers to inquire about their experience, asking them to self-identify as a community or academic reviewer. The survey excluded cycle 1, as we had not yet developed the survey, and cycle 5, as all reviewers had participated in previous review cycles.

OUTCOMES

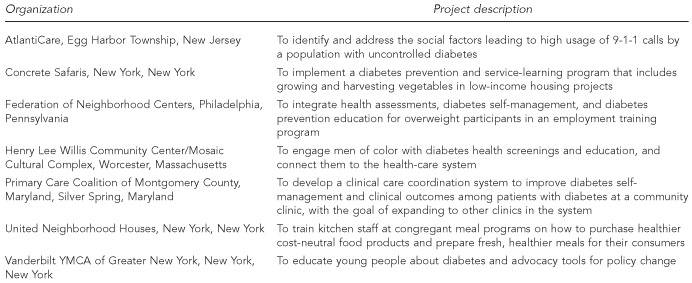

IMPACT received a total of 135 applications from community-based organizations located throughout the Northeast during the five cycles and funded 17 (2–4 each cycle) one-year projects focused on or incorporating diabetes prevention or control strategies targeting African American and Latino populations. Grants were for $25,000–$30,000 each and provided $500,000 in total funding. The type and focus of the funded projects varied in terms of scope, purpose, and SDH sectors and categories (Figure). Some organizations focused on diabetes prevention or control, including healthy eating and physical activity, and proposed using funds to continue or expand their work. Others clearly did not have any focus on diabetes, but the funding was an opportunity for those groups to expand into this area.

Figure.

Examples of projects funded through the Communities IMPACT Diabetes Center:a East Harlem, New York, 2008–2012

aOne of 18 Centers of Excellence to Eliminate Disparities funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2007

YMCA = Young Men's Christian Association

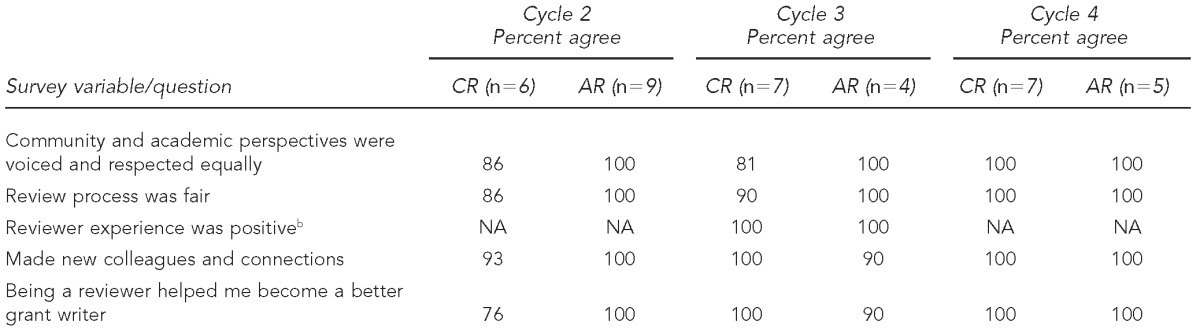

As shown in the Table, the reviewer surveys demonstrated positive and improving results. Most (n=38/47) eligible grant reviewers completed the survey. In cycle 2, 55% (n=6/11) of community reviewers responded compared with 100% (n=9/9) of their academic counterparts, despite multiple reminders to complete the survey. However, for cycles 3 and 4, we obtained a 100% response rate from community reviewers but only a 67% (n=4/6) and 71% (n=5/7) response rate for cycles 3 and 4, respectively, from academic reviewers. Of the reviewers who responded, a majority of them, both community and academic, stated that community and academic members' perspectives were voiced, listened to, and respected equally, and that the review process was fair and a positive experience. Nearly all made new connections and believed that being a grant reviewer helped them become a better grant writer.

Table.

Results from grant reviewer surveys in cycles 2–4 of the grant funding process of the Communities IMPACT Diabetes Center:a East Harlem, New York, 2009–2011

aOne of 18 Centers of Excellence to Eliminate Disparities funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2007

bQuestion only included in cycle 3

CR = community reviewer

AR = academic reviewer

NA = not applicable

Furthermore, community reviewers reported becoming skilled at making the distinction between an organization seeking funding based largely on its more subjective characteristics (i.e., “doing good for the community” or “good people who wouldn't waste money are in charge”) and an organization seeking funding based on having a strong project idea and clear goals, objectives, an implementation strategy, and an evaluation plan. Their increasing expertise as reviewers did not, however, diminish their strong sense of community focus. Academic reviewers learned to “peer underneath the hood” of a paper application through site visits to see both organizations that outshone their written proposals and those whose actual programs did not live up to their writing skills.

Many projects had positive outcomes. Two such projects are highlighted subsequently. Though they focused on different areas, each project had a strong impact and a high likelihood of sustainability.

-

Cooking for Healthy Communities. This pilot project was a collaboration between United Neighborhood Houses, a large human services organization in New York City, and The Children's Aid Society, a multiservice agency serving children and families throughout New York City. The project participants used IMPACT funding to train congregate meal cooks in healthy food preparation, with a focus on cost-neutral increases in the use of fresh, healthy food items. The initiative brought a new approach to disease prevention and health promotion to member agencies and provided program administrators, cooks, and other staff with the knowledge, skills, and technical assistance to improve the nutritional quality of their food purchasing and menu development practices.

The program built the organizations' capacity to offer healthier meals, challenged the organizations to reorganize strategies to purchase fresh produce, and changed regulatory and reporting structures to allow for the use of healthy ingredients previously not permitted, such as canned beans. All participating sites documented improvements in their food purchasing and preparation. The sites also began to develop and implement broader organizational changes, such as rethinking the use of food within their wider programming and involving regulatory agencies in addressing and improving meal requirements at funded programs throughout the city.

Job Opportunity Investment Network Education on Diabetes in Urban Populations (JOINED-UP). Federation of Neighborhood Centers is a community partner in a regional Job Opportunity Investment Network (JOIN) workforce development initiative in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The Federation used IMPACT funding to move into a new area of focus—adding diabetes and obesity prevention and control to its job training program. The group viewed this strategy as a way to improve the potential of job trainees to obtain and maintain work by improving their health, and to inspire lifestyle changes among a hard-to-reach population (i.e., low-income, minority, young, and middle-aged men). To this end, the Federation developed the JOINED-UP program and used the funding to support healthy lifestyle individualized counseling; interactive, group skill-building sessions; and health screenings for body mass index, glucose, blood pressure, and lipids as a new required component of employment training for low-skilled men. At baseline, 68% of program participants were overweight or obese, 63% were newly identified as pre-diabetic, and 11% were identified as diabetic. In addition, 37% were smokers. Following the program, self-report surveys revealed that 26% of participants previously without a primary care provider had obtained one, 70% had increased their physical activity, 90% had increased their fruit and vegetable consumption, 33% had decreased their smoking, 26% had lost measurable weight, 73% noted substantial health improvement, and 70% noted an increased ability to control their health. The Federation used these pilot data to secure additional funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to expand the initiative.

DISCUSSION

Few examples of partnership models exist that use academic and community members equally in the grant review process.8,9 A limited number of community reviewers are invited to join existing grant award processes.10 IMPACT developed a partnered process to award grants to qualified community groups to support innovative projects that address the social determinants of diabetes among African American and Latino populations. Partners worked collaboratively and equitably to develop an RFP form and merit review system, review applications, conduct site visits, and select grantees. Through this process, the team developed a robust community-partnered grant system, which partners found to be fair and inclusive. The system increased their capacity to review and write grants, and funded many innovative interventions. The grant funding process also expanded capacity among those already engaged in prevention work, and used the potential for funding to encourage new organizations to consider adding prevention to their community service agenda.

The decision to use both community and academic reviewers, although reflective of IMPACT's overall philosophy, took commitment, time, and effort to implement. Initially, there was skepticism among academic members that the community members would progress to grant reviewer status, given their limited previous experience with science and evaluation. Similarly, community residents were skeptical that academic members could move beyond prioritizing professionally written “grant sales” proposals to recognize the competence and promise of proposals written by grassroots organizations. Both academic and community members were able to overcome these initial concerns, exceeding their counterparts' expectations in both areas.

The process of co-learning, as exemplified in IMPACT's community-academic partnership, is a basic tenet of community-based participatory research.11 CBPA draw on Freirean concepts of power relationships between researchers and the object of research, which can transform research subjects into active participants capable of resolving problems and changing the society in which they live.2,12 Through this process of mutual learning, participants are brought into research as owners of their own knowledge and are empowered to take action.2 When community members share equally in grant decision-making, they are further empowered to select the research topics of most relevance to local concerns and thereby bypass what has been termed the “social production of science,” where the theories and methods employed in research are influenced by scientists' worldviews and interests. This process results in improved targeting of interventions that address locally specific SDH.13

IMPACT facilitated co-learning as community members spearheaded seminars on how to respond to RFPs, technical assistance sessions on preparing grant budgets, and site visits to avoid sole reliance on written proposals that could lead to funding of organizations that were not capable of carrying out the proposed programs but which had better grant writing skills or resources to hire grant writers. Simultaneously, members learned to separate appreciation and respect for the work of an organization from the merits of their application (i.e., a great organization can submit a mediocre grant).

With each cycle of funding, the subcommittee met to review and revise the documents and process. Each cycle was improved and strengthened through the sharing of diverse perspectives in a nonintimidating environment, without the traditional trappings of a process dominated by an academic hierarchy. Additionally, the work of funded groups improved with site visits and closer monitoring of recipients. This monitoring grew out of a shared realization that some recipients had difficulty getting started; thus, the subcommittee needed to provide proactive, not reactive, technical assistance to prevent delays, avert problems, enhance the quality of activities and program evaluation, and look toward sustainability and future funding.

Committee members recruited additional reviewers, mentored them, and helped grow community capacity. All committee members were invited to participate in writing papers, drafting newsletters, and making presentations. Community residents and academic researchers both took pride in the accomplishments of the committee, reporting back to the main task force as well as participating in other dissemination activities. Feedback from the funding agency program officer and other members of the REACH U.S. community helped to validate the committee's hard work and resulted in a grant process that was strong, effective, and used as a model by other REACH programs.

As a result of this co-learning process, community reviewers not only learned the grant review process, but also felt they were serving their communities by making the process more transparent, equitable, and representative of their communities. A strength of the peer-review system is that participating in the process allows academic reviewers to “decide their own fate by determining what good science is.”14 Likewise, community participation in grant review allows members to decide the fate of communities, oftentimes ones that are similar to their own.

CONCLUSION

This article details how community members and academic researchers can capitalize on the strengths, skills, and knowledge of each group to create a successful grant funding model that can better target resources toward addressing disparities related to SDH. Our partnered approach to community-academic grant review promoted trust and respect for each group's viewpoint and simultaneously served to build community members' capacity for effective grant writing and academicians' sensitivity to the support needed by grassroots organizations to successfully apply for and obtain grant funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all of the reviewers who participated in the legacy grant review process over the years and the staff of the Communities IMPACT Diabetes Center for their contributions.

Footnotes

This article was supported by Cooperative Agreement #5U58DP001010-05 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and grant #UL1TR000067 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Center for Research Resources. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of CDC or NIH.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization, Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Final report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva: WHO; 2008. [cited 2012 May 1]. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Also available from: URL: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241563703_eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cornwall A, Jewkes R. What is participatory research? Soc Sci Med. 1995;4l:1667–76. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00127-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, editors. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2005. Methods in community-based participatory research for health. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallerstein NB, Duran B. Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promot Pract. 2006;7:312–23. doi: 10.1177/1524839906289376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wallerstein N World Health Organization Europe. Health Evidence Network report. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2006. [cited 2012 May 1]. What is the evidence on effectiveness of empowerment to improve health? Also available from: URL: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/74656/E88086.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horowitz CR, Robinson M, Seifer S. Community-based participatory research from the margin to the mainstream: are researchers prepared? Circulation. 2009;119:2633–42. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.729863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gelmon SB, Holland BA, Seifer SD, Shinnamon A, Connors K. Community-university partnerships for mutual learning. Michigan J Community Service Learning. 1998;5:97–107. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calleson DC, Jordan C, Seifer SD. Community-engaged scholarship: is faculty work in communities a true academic enterprise? Acad Med. 2005;80:317–21. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200504000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Higgins DL, Metzler M. Implementing community-based participatory research centers in diverse urban settings. J Urban Health. 2001;78:488–94. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wallerstein N, Bernstein E. Introduction to community empowerment, participatory education, and health. Health Educ Q. 1994;21:141–8. doi: 10.1177/109019819402100202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freire P. Pedagogy of the oppressed. 20th anniversary ed. New York: Continuum Publishing Co.; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krieger N. Epidemiology and the web of causation: has anyone seen the spider? Soc Sci Med. 1994;39:887–903. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90202-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Porter RE. What do grant reviewers really want, anyway? J Res Adm. 2005;36:5–13. [Google Scholar]