Abstract

Background:

Cytological artifacts are important to learn because an error in routine laboratory practice can bring out an erroneous result.

Aims:

The aim of this study was to analyze the effects of delayed fixation and morphological discrepancies created by deliberate addition of extraneous factors on the interpretation and/or diagnosis of an oral cytosmear.

Materials and Methods:

A prospective study was carried out using papanicolaou and hematoxylin and eosin-stained oral smears, 6 each from 66 volunteer dental students with deliberate variation in fixation delay timings, with and without changes in temperature, undue pressure while smear making and intentional addition of contaminants. The fixation delay at room temperature was carried out at an interval of every 30 minutes, 1 day and 1 week and was continued till the end of 1 day, 1 week, and 1 month, respectively. The temperature variations included 60 to 70°C and 3 to 4°C.

Results:

Light microscopically, the effect of delayed fixation at room temperature appeared first on cytoplasm followed by nucleus within the first 2 hours and on the 4th day, respectively, till complete cytoplasmic degeneration on the 23rd day. However, delayed fixation at variable temperature brought faster degenerative changes at higher temperature than lower temperature. Effect of extraneous factors revealed some interesting facts.

Conclusions:

In order to justify a cytosmear interpretation, a cytologist must be well acquainted with delayed fixation-induced cellular changes and microscopic appearances of common contaminants so as to implicate better prognosis and therapy.

Keywords: Artifacts, contaminants, cytosmear, degeneration, delayed fixation

Introduction

Artifacts are structures or features which are being produced by the processing of a tissue,[1] and may interfere with normal histological interpretation and/or diagnosis. These are not present in normal tissue and generally arise on a surgeon's chair or pathologist's laboratory from outside sources. Artifacts can interfere with histological assessment by changing the tissues appearance, mimicking other known tissues, creating confusion due to their unidentifiable structure, and/or hiding histological landmarks. These have been well studied at the tissue level but not so well at the cytological level.

Cytology is a simple, quick, non-invasive method for tissue analysis of shed cells from an epithelial surface.[2] Although an adjunct to the gold standard histology, cytology is a very commonly performed procedure in clinical practice. The importance of art and science of cytosmear making and its proper handling is thus imperative. Cytology, if performed with accuracy, can play an important role in early diagnosis. Mishandling, delay in processing, or injudicious contamination might lead to misinterpretation, flawed diagnosis, or false-positive/negative results.

There are many factors which can affect a cytosmear unintentionally by a qualified health personnel or due to unawareness of an auxiliary staff. The duration between collection and preparation of the sample before cellular damage occurs depends on pH, protein content, enzymatic activity, and the presence or absence of bacteria. Regardless of the collection technique, specimen obtained from the mouth should be processed immediately.[3] Thus, rapid fixation of smears is necessary to preserve cytologic details of cells. To achieve this, a minimum of 15-minute immediate fixation prior to staining is essential.[3] Similarly, the importance of identifying an extraneous factor induced during smear processing, from pathogens and pathologists, needs recognition. This study was conducted with two-fold objectives; first, to observe changes in cells caused by delayed fixation/addition of external factors and second, to determine the impact of these mistakes on scientific interpretation and/or diagnosis.

Materials and Methods

Cytological study of oral cells is a nonaggressive technique that is well accepted by the patient.[4] The prospective study included six (06) smears prepared each from the buccal mucosa of 66 healthy volunteers in the age range of 20 to 30 years (mean age, 24 years) with no history of oral and/or systemic diseases such as diabetes, malignancy, anemia, etc. All investigations on the subjects included an informed consent and patient's anonymity is preserved.

From every six smears prepared, two control smears were immediately stained following 15-minute fixation, whereas two each were stained with standard Papanicolaou (Pap) and H and E and were used in the study. Broadly, the study was divided into two main groups as discussed in Tables 1 and 2. Group 1 consisted of cytosmear in which fixation was delayed and Group 2 with addition of external factors. Smears were initially examined under light microscope (Olympus BX41 digital microscope) under 40X and 100X magnifications. Cytological assessment of degeneration was done by two screeners in a blinded fashion (without knowing the time of delay for each preparation). Cellular features found in degenerative change which were chosen for the assessment were contaminants, bacteria and fungi, cytoplasmic inclusions, disintegrating cytoplasm, vacuolated cytoplasm, and presence of karyolysis, karyorrhexis, and pyknosis.

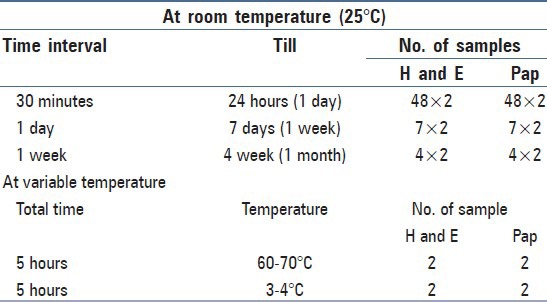

Table 1.

Group 1 cytosmears along with their fixation delay timing and temperatures

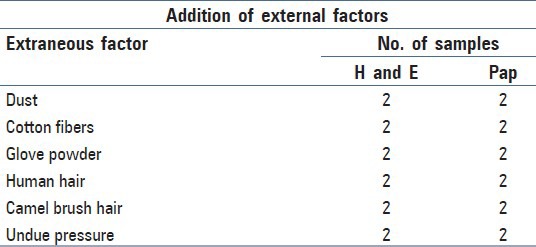

Table 2.

Group 2 cytosmears along with the extraneous factors added

Results

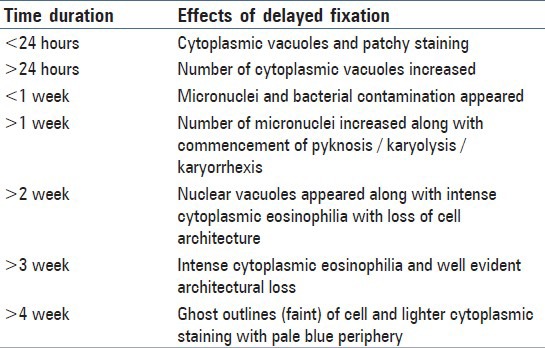

All the control cytosmears showed good staining quality and excellent preservation, whereas the study cytosmears of group 1 showed staining and architectural changes due to degeneration as depicted in Table 3 and Figure 1.

Table 3.

Effects of delayed fixation in the hours, days, and week time on the cytological oral smears

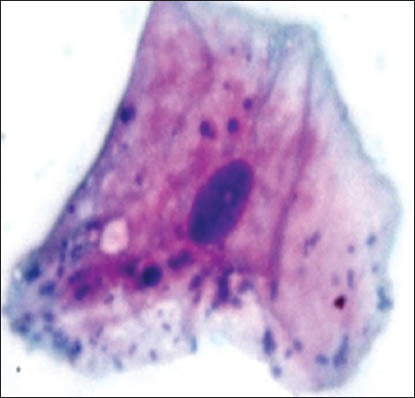

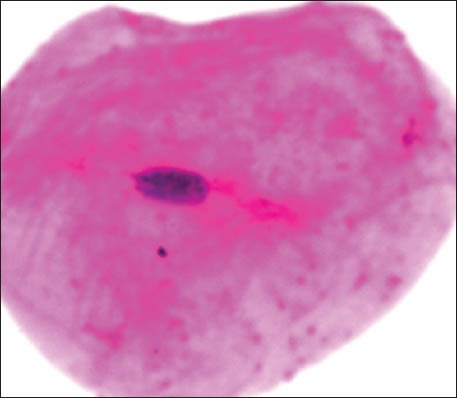

Figure 1a.

Cytoplasmic vacuolization with micronuclei

Figure 1d.

Karyorrhexis

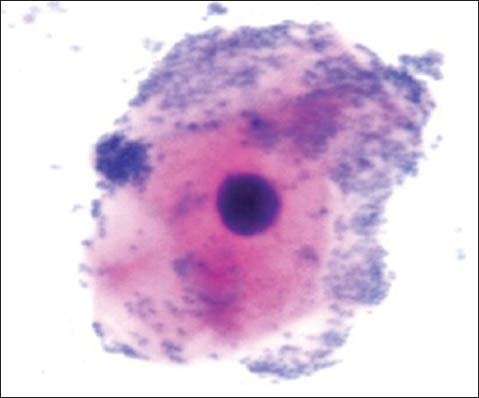

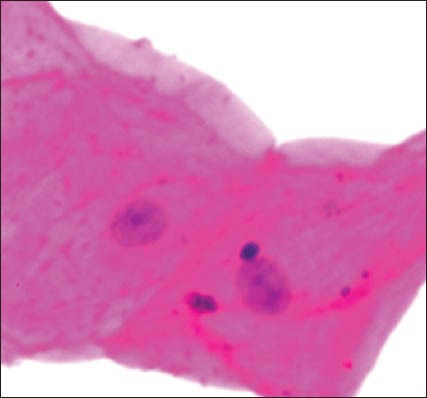

The group 1 cytosmear kept at room temperature showed cytoplasmic changes in 2 hours along with small vacuoles and patchy distribution of Pap stain, as shown in Figure 1a. In 24 hours, the cytoplasmic vacuoles increased in number and size. Within a week, i.e., on 4th day, micronuclei appeared along with growth of bacterial colonies invading from periphery toward the center [Figure 1a and b]. Deterioration of staining quality soon followed these changes and was observed in slides delayed for fixation for more than a week. However, there was a delay in nuclear signs of degeneration which appeared gradually as karyolysis and karyorrhexis on the 14th day followed by pyknosis [Figure 1c-e]. The following week exhibited nuclear vacuolization on day 18 and intense cytoplasmic eosinophilia on day 24 along with loss of cellular architectural details. Faint outlines of nucleus and cell with loss of cellular details followed a distinct [Figure 1f] cytoplasmic staining pattern exhibiting a pale blue periphery and pink center in the fourth week.

Figure 1b.

Bacterial invasion

Figure 1c.

Karyolysis with micronuclei

Figure 1e.

Pyknosis

Figure 1f.

Ghost outlines of cell

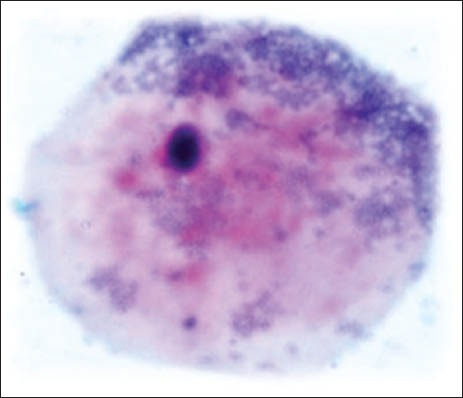

The group 1 cytosmears kept at temperature of 50 to 60°C with 5-hour fixation delay cells appeared wrinkled/shrunken with staining pattern similar to group one's fourth week cytosmear kept at room temperature, it appeared pink centrally and blue at the periphery; chromatin condensation and cytoplasmic vacuoles were also appreciated [Figure 1g]. However, at 3 to 4°C and delayed fixation of 5 hours, many nuclear vacuoles appeared in a wrinkled cell with a well-preserved cytoplasm [Figure 1h].

Figure 1g.

Wrinkled cells with cytoplasmic vacuolization

Figure 1h.

Wrinkled cell with nuclear vacuoles

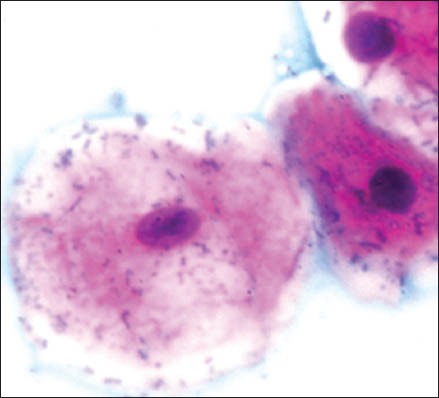

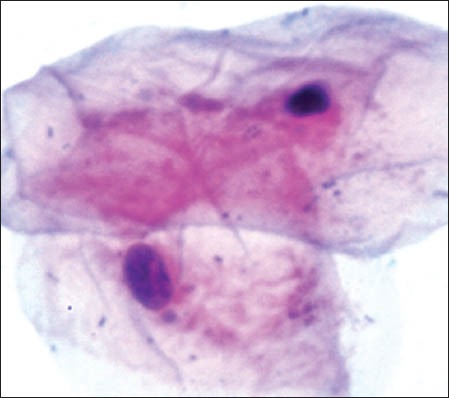

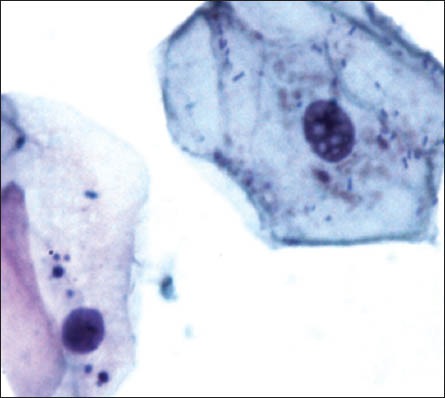

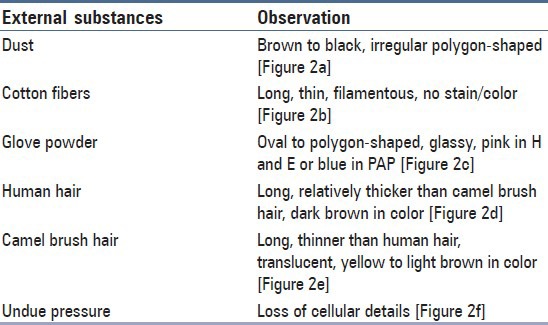

Table 4 and Figure 2a-f represent the contaminants in cytosmear which were intentionally induced.

Table 4.

Table representing the effects of extraneous factors on cytosmears

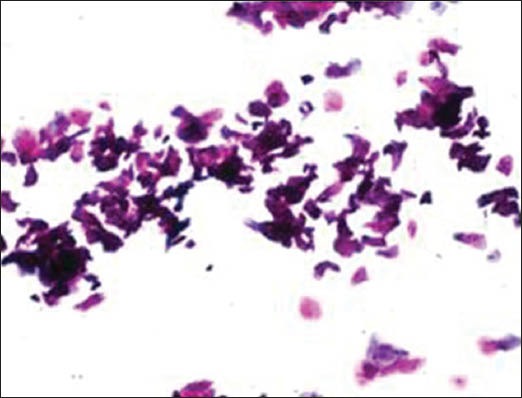

Figure 2a.

Dust particles

Figure 2f.

Undue pressure

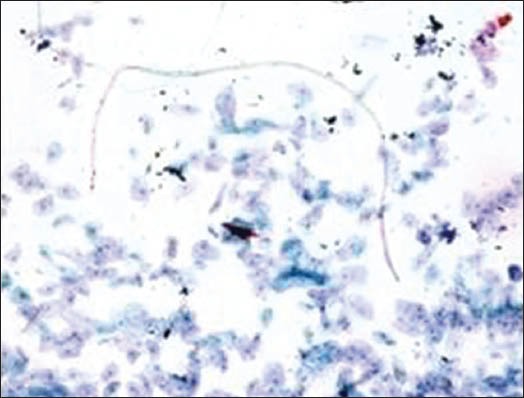

Figure 2b.

Cotton fiber

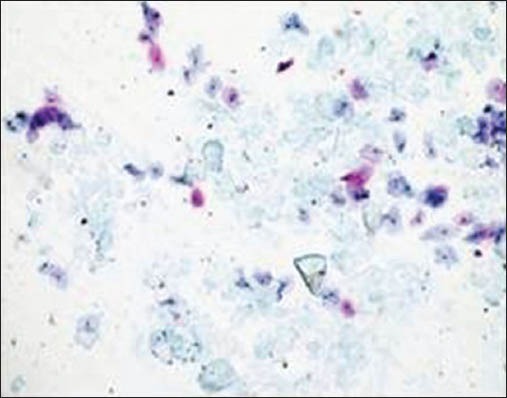

Figure 2c.

Glove powder

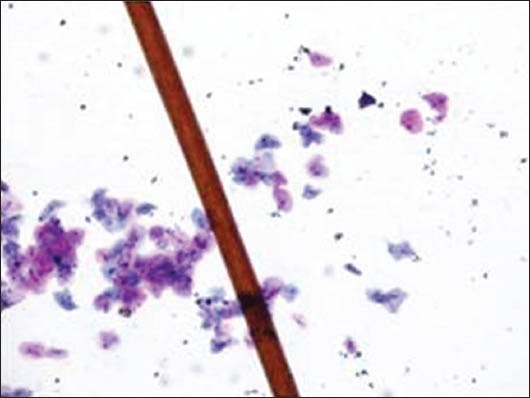

Figure 2d.

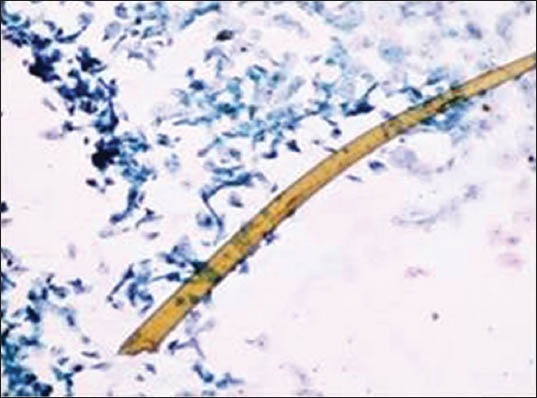

Human hair

Figure 2e.

Camel brush hair

Discussion

The significance of proper handling of biopsy has been well documented and well supported in literature by case reports along with photomicrographs. However, the cytological artifacts have received less attention to the best of our knowledge. An essential part of all histological and cytological techniques is preservation of cells and tissues as they naturally occur.[5] Although every laboratory protocol for smear preservation would mention the importance of immediate fixation, it ironically lacks the relevant data for reference if fixation delay occurs. Thus, the purpose of this study was to induce artifacts intentionally into the smears to obtain reference data by delaying fixation timings and by the incorporation of extraneous factors.

Cytological artifact is defined as an artificial structure or cellular alteration on a prepared microscopic slide as a result of an extraneous factor. The importance of cytology as a valuable and indispensable tool for interpretation of oral lesions cannot be underestimated. Degenerative changes which occur with delayed fixation and misdiagnosis due to extraneous agents are often considered to be responsible for most false diagnosis.[3]

Problems caused by fixation delay can result in loss of chromatin, halo, fading, or complete disappearance of nuclei. There may be cell shrinkage, disruption of the cytoplasm, and artifactual spaces around cells, whereas incomplete fixation often leads to the appearance of a smudgy nuclei.[6] Our study revealed numerous, partially to completely degenerated cells within few hours of fixation delay at room temperature without nuclear and cytoplasmic alterations. Cytoplasmic vacuolization and patchy staining were the first few signs of degeneration to be seen in 2 hours which later increased in number and size. Micronuclei and bacterial colonies invaded from periphery toward the center on day 4 and commencement of karyolysis, karyorrhexis, and pyknosis occurred after one week. On day 14, nuclear vacuoles appeared along with intense cytoplasmic eosinophilia followed by loss of cellular architecture. In one-month time, ghostly outlines of cells remained. High and low temperature variation with 5-hour fixation delay caused cell shrinkage, cytoplasmic vacuoles and chromatin condensation, and appearance of nuclear vacuoles along with wrinkling of cells.

Thus, for obvious reasons, immediate fixation is necessary to minimize any cellular changes which can complicate the subsequent interpretation. As already known, immediate fixation prevents degeneration of cells from autolytic enzymes and thus preserves cells as close to the living state as possible.[3]

The majority of the extraneous artifacts presented in the study are common contaminants which can be mistakenly incorporated during processing. Contaminants like cotton fibers, human hair, and camel brush hair can be mistaken for fungal hyphae, filamentous or thread-like pathogens and thus should be taken into account while establishing differential diagnosis.[7] Human hairs are long filamentous and cylindrical in shape. Central medulla appears dark while the outer cortex appears lighter, in deep-focusing position. If the focus is changed, medulla appears light and the cortex dark. In gray hairs, the medullary keratin is absent and is replaced by air. Cotton fibers can be a suture material of varying types incorporated at surgical site and appear as long filamentous, spirally twisted at intervals and ribbon-like structures. Two faint lines appear to enclose a lighter central zone throughout the twisted fiber; there is no medulla, unlike hair.[8] Undue pressure often under untrained hands or while using incorrect methods of smear making like applying continuous, rough circular motion with tongue blade result in crush artifact which may lead to cell destruction or cytological alterations. These cells might mimic areas of ulceration/necrosis or broken down epithelial cells. Glove powder/starch granules may resemble epithelial cells in cytologic smears and appear as refractile, glassy, polygonal/oval/pear-shaped bodies with a hilum at the narrow end, generally about 5 to 20 micrometer in diameter,[8,9] wherein dust particles (unevenly light/dark, brown to black in color, 8 to 10 micrometer in diameter, angular and irregularly polygonal with sharp edges) should also be ruled out as a contaminant for the new cytologists.[8]

For knowing the importance of recognizing the cytological smear correctly, it is necessary to present these artifacts which should be taken into account in view of the possible confusion to which they may give rise to.[3]

Conclusions

Although immediate fixation is recommended, delay in fixation for 1 hour and 30 minutes does not seem to effect the preservation and the quality of staining at light microscopic level. The knowledge of the microscopic features of the contaminants is important to identify them confidently so as to avoid over valuation or any other possible confusion. This information can provide an important interpretation of pathological material.[10] The presence of artifacts in cytological smears is important, as this finding, although sometimes accidental, may have implications on prognosis and therapy. Thus, the purpose of this study is to give cytologist the morphological criteria required for them to differentiate certain artifacts, regularly observed in smears.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.McInnes E. Artefacts in histopathology. Comp Clin Path. 2005;13:100–8. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yerlagudda K, Kamath VK, Satelur K. Morphological assessment of oral cytological smears before and after application of toluidine blue in smokers and nonsmokers. Int J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2012;3:8–14. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmed HG, Tom MA. The consequence of delayed fixation on subsequent preservation of urine cells. Oman Med J. 2011;26:14–8. doi: 10.5001/omj.2011.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mehrotra R, Gupta A, Singh M, Ibrahim R. Application of cytology and molecular biology in diagnosing premalignant or malignant oral lesions. Mol Cancer. 2006;5:11. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-5-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 5.Nowacek JM. Fixation and Tissue Processing. In: Kumar GL, editor. Education Guide Special Stains and H and E. 2nd ed. California: Dako; 2010. p. 141. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carson FL, Haladik C. 3rd ed. Texas: American Society for Clinical Pathology Press; 2009. Histotechnology: A self-instructional text. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoeven KHV, Bertolini PK. Prevalance, identification and significance of fiber contaminants in cervical smears. Acta Cytol. 1996;40:489–5. doi: 10.1159/000333904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghai CL. 5th ed. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd; 2003. A textbook of practical physiology. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jadhav KB, Gupta N, Ahmed BR. Maltese cross: Starch artifact in oral cytology, divulged through polarized microscopy. J Cytol. 2010;27:40–1. doi: 10.4103/0970-9371.66698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pattari PK, Dey P. Facts about artefacts in diagnostic pathology. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2002;45:133–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]