Abstract

Introduction:

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cervical cancer remain important health problems. Cervical cytology by Papanicolaou (Pap) smears is an effective means of screening for cervical premalignant and malignant conditions.

Aim:

The aim of this study was to assess the prevalence of cervical dysplasia in pre- and postmenopausal women in western Uttar Pradesh and to find out risk factors as far as possible.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 4,703 cases were enrolled, cervical scrape smears were collected and stained using Papanicolaou's method and hematoxylin and eosin stain. The emphasis was put on epithelial abnormalities and smears were classified according to The Bethesda System 2001.

Results:

81.06% (3812) smears were satisfactory according to The Bethesda System. Maximum numbers of cases (40.37%) were in age group 30-39 years. The epithelial abnormalities constituted 3.23% of all cases. Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) formed the largest number (1.36%), while high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) formed 0.91%. Eleven cases of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) were detected. The study has shown a relatively high prevalence of epithelial abnormalities in cervical smears with increasing age, parity, early age at first coitus (<20 year), and lower socioeconomic status in symptomatic women with clinical lesions on per speculum examination.

Conclusion:

Epithelial abnormalities of cervix are not uncommon in our setup and are associated with early age at marriage and parity.

Keywords: Carcinoma cervix, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, HSIL, LSIL, papanicolaou smear

Introduction

Carcinoma cervix worldwide accounts for 15% of all cancers diagnosed in women.[1] Cervical cancer is one of the leading cancer in women with the estimated 5.0 lakhs new cases every year of which 80% occur in developing countries.[2] In India, it is estimated that the number of new cases are over 140,000.[3] Cancer cervix occupies the top rank or second among cancers in women in developing countries, whereas in the affluent countries cancer cervix does not find a place even in top five leading cancers in women. Seventy percent or more of these cancers are in the stage 3 or higher at the time of diagnosis. The role of Papanicolaou (Pap) smear as a cancer screening tool for the cervix has been substantiated by several studies in the last 50 years,[4,5] and the method has resulted in falling incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in the developed world.[6,7,8] Time trend analysis of a 10-year data in Bangalore, Bombay, and Madras and a 4-year data in Delhi did not reveal a statistically significant decrease or increase in the incidence of uterine cervical cancer for most of the age groups.[9] Therefore, the data on the prevalence of cervical epithelial abnormalities in various population in this country is not known. There is an urgent need for initiation of community screening and educational programs for the control and prevention of cervical cancer in India.[10]

Therefore, objective of this study was to assess the prevalence of cervical dysplasia in pre and postmenopausal women in western Uttar Pradesh.

Materials and Methods

A total of 4,703 cases were enrolled. Detailed clinical history and pelvic examination (per speculum and per vaginal) were done. Cervical scrape smears were collected using Ayer's spatula or endocervical brush, the smears were fixed in absolute alcohol and stained using Papanicolaou's method and hematoxylin and eosin (H and E) stain. The epithelial abnormalities were classified according to The Bethesda System 2001.[11] All the cases above 18 years of age were studied and grouped as pre- and postmenopausal. Pregnant women, menstruating women, women with invasive carcinoma at the time of clinical evaluation, and women previously treated for cervical neoplasm were excluded from the study.

Results

In our study, we had examined 4,703 cases; out of which 3,812 (81.06%) smears were satisfactory according to The Bethesda System. The epithelial cell abnormalities constituted 3.2% of all cases and rest of 3,690 cases (96.8%) fell in the category of negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy (NILM).

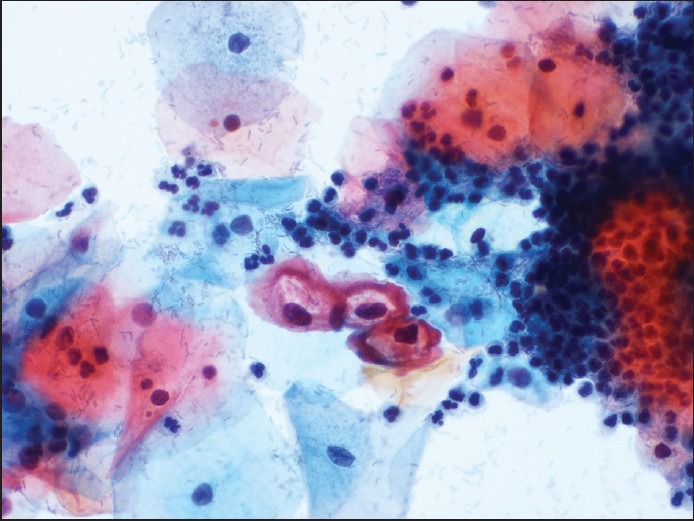

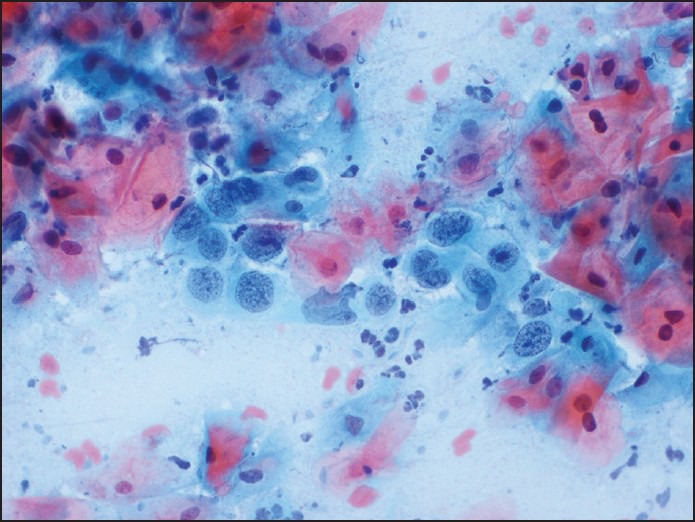

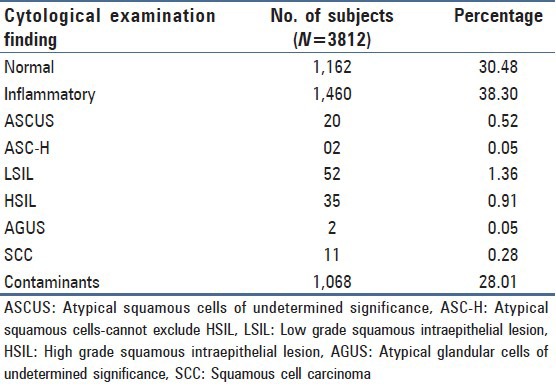

Maximum number of cases (40.37%) were in age group 30-39 years, followed by 35.96% in age group 20-29 years. The epithelial abnormalities including (atypical squamous and glandular cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS), atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance (AGUS), low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL), high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL), and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)) constituted 3.2% of all cases. LSIL [Figure 1] formed the largest number 1.36%, while HSIL [Figure 2] formed 0.91%. Eleven cases of SCC were detected [Table 1]. Different risk factors associated with dysplasia and cervical carcinoma detected in the present study were analyzed in detail. The findings are summarized below.

Figure 1.

Photomicrograph from a case of low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion showing koilocytes (Pap, × 400)

Figure 2.

Photomicrograph showing high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (Pap, × 400)

Table 1.

Distribution of cervical cytological findings in the subjects

Age

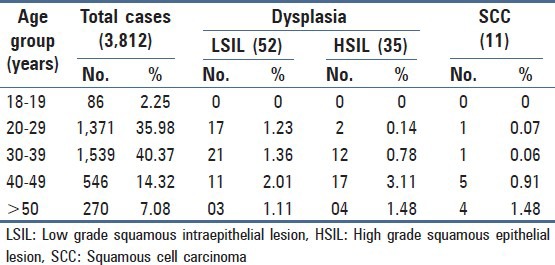

The frequency of dysplasia and cervical carcinoma in relation to age is shown in Table 2. A progressive rise was seen in the frequency of cytopathological abnormalities with increasing age, and maximum frequency of LSIL, HSIL, and cervical carcinoma was observed in age above 40 years.

Table 2.

Age-wise distribution of smears and prevalence of dysplasia

Age at first coitus

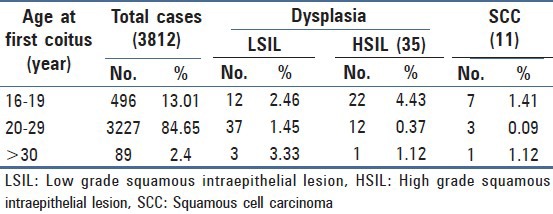

The frequency of dysplasia and cervical carcinoma in relation to age at first coitus is shown in Table 3. The frequency of LSIL was maximum in age group >30 years at first coitus, while HSIL and cervical carcinoma was maximum in patients who were <20 years at the time of first coitus.

Table 3.

Association of dysplasia with age at first coitus

Parity

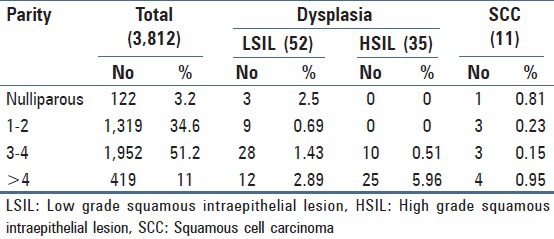

The frequency of dysplasia and cervical carcinoma in relation to parity is shown in Table 4. There was progressive rise of dysplasia with increasing parity, it was maximum in parity above 3.

Table 4.

Association of dysplasia with parity

Gynecological symptoms

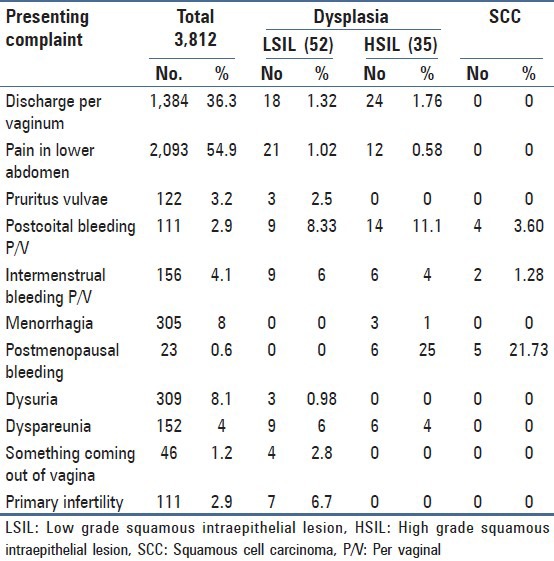

The frequency of dysplasia and cervical carcinoma in relation to gynecological symptoms is shown in Table 5. The frequency of dysplasia LSIL was higher in symptomatic women complaining of postcoital bleeding per vaginum, while frequency of HSIL and carcinoma cervix was highest with postmenopausal bleeding.

Table 5.

Association of cervical dysplasia with presenting complaint

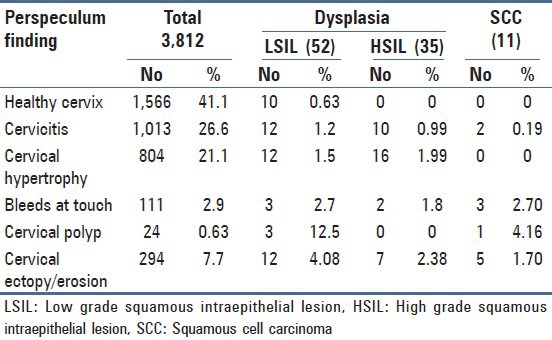

Per speculum findings

The frequency of dysplasia and cervical carcinoma in relation to per speculum finding is shown in Table 6. The frequency of dysplasia and carcinoma cervix was very high in women with clinical lesions of cervix and the difference was statistically highly significant (P < 0.01), thus it was amply clear that clinical lesions of cervix harbor a large number of dysplasia and if such women are subjected to mandatory cytological evaluation, the burden of carcinoma cervix can be significantly reduced. Prevalance of epithelial abnormalities were ASCUS 0.52%, atypical squamous cells-cannot exclude HSIL (ASC-H) 0.05%, AGUS 0.05%, LSIL 1.36%, HSIL 0.91%, and for SCC 0.28%.

Table 6.

Association of dysplasia with per speculum finding

Religion

Out of 3,812 cases; 2,744 smears (71.98%) were from Hindu patients while 1,060 smears (27.8%) belonged to Muslims and eight cases were from other religion. In Hindus, percentage positivity for LSIL and HSIL was 1.31 and 0.67%, respectively which was slightly higher in Muslims (LSIL 1.42%, HSIL 1.60%), but it was not statistically significant.

Socioeconomic status

All these 3,812 cases were classified according to Kuppuswamy classification into upper, middle, and lower class. Prevalence of LSIL, HSIL, and SCC in upper class was 1.31, 0.34, and 0; in middle class 1.02, 0.80, and 0.2%; in lower class it was 1.62, 0.94, and 0.4%, respectively. Though the percentage positivity of cervical dysplasia was higher in lower socioeconomic group but it was not statistically significant from the other two socioeconomic groups.

Smoking

The prevalence of dysplasia was more in smokers (17.24%) as compared to nonsmokers (2.61%), but the difference was not statistically significant. As the number of patients were very few who smoked, the association of smoking with dysplasia cannot be predicted.

Discussion

Uterine cervix is ideal for screening due to easy accessibility of cervix for inspection, palpation, exfoliative cytology, and screening. Cancer cervix is a preventable and curable disease due to effective screening methods available and a long preinvasive phase of the disease and various treatment modalities available. Cervical cancer screening represents one of the great success stories in cancer prevention.

We studied Pap smears of 4,703 females. Out of which only 81.06% (3,812) were found to be satisfactory. Only 13.94% smears were unsatisfactory, the proportion of inadequate smears ranged from 0.2-5%[12,13,14,15,16] in other studies.

With reference to the epithelial abnormalities, which was the main reason for advocating routine cervical smear examination, the prevalence studies around the world has shown a wide range from as low as 0.98%[17] to as high as 15.6%.[18] No consistent pattern emerged in these studies both in developed and developing countries. Hence, within these countries such as US prevalence rates of cervical dysplasia range from 2.3-6.6%[19] in Middle East 1.65-7.9%,[20,21,22] in Israel 0.98 to 4.41%,[23,24,25] and in India 1.392-7.8%[26,27,28,29]; while in our study it was 3.23%.

The reasons for these variation could be many including criteria employed for diagnosis, the quality checks used, intrinsic differences in the population studied including the prevalence of risk factors and the numbers studied which have ranged from as few as 419[18] to as high as 297,849.[17] A more detailed analysis showed the prevalence of LSIL (1.36%) was similar to many other studies from Zimbawe, Saudi Arabia, and USA. In our study, prevalence of LSIL was more common in premenopausal age group 40 years. It was noticed that in the majority of studies including ours, prevalence of HSIL formed less than 1% of the abnormal smears. Prevalence of HSIL was higher in postmenopausal women in our study.

The percentage of dysplastic smears was found to be very high in women who were married at age <20 years, thus high parity coupled with early age at first coitus appeared to play a significant role in progression of cervical dysplasia. The studies of Castapeda-Ipiguez et al.,[30] have also pointed out the number of pregnancies as a great risk factor in the development of cervical dysplasia. As our study showed that frequency of cervical cancer was higher in women with postmenopausal bleeding, hence such women should always undergo mandatory cytological examination.

A large number of workers[31,32] found smoking as one of the major risk factor. In our study, dysplasia was found to be slightly more frequent in smokers as compared to nonsmokers, but statistically the difference was not significant. As regards association of smoking with dysplasia, it is very difficult to comment upon as the number of smoker females were too less in this study. The role of circumcision and carcinoma of cervix has been emphasized by a large number of workers in the past[33,34,35] who reported carcinoma cervix to be more common in Hindus than in any other religion. The number of positive smears was more common in Muslims (3.20%) in comparison to Hindus (2.26%), but the difference was not statistically significant in this study. Terris et al.,[36] also found no significant difference in the circumcision status of marital partners of cases and control. It has been documented earlier that cancer is common in low socioeconomic class in whom the component of poverty, overcrowding, inadequate food, and poor personal hygiene are contributing factors. The increased risk with low socioeconomic status is attributed to a lack of screening, failure to treat precancerous conditions, and lack of knowledge about prevention of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection.[37] In our study, an inverse relation with socioeconomic status was observed as also in other studies.

It has been established that low grade dysplasia is usually asymptomatic. The common complaints in high grade dysplasia are postmenopausal bleeding and intermenstrual and postcoital bleeding per vaginum.[38] In our study also, the most common complaint in both LSIL and HSIL was postcoital bleeding and postmenopausal bleeding per vaginum and on per speculum examination, most common finding was cervical polyp. In the past also, visual inspection of the cervix had been stressed by Sankaranarayanan et al.[39]

Thus screening of both pre and postmenopausal women should be made mandatory as it helps in picking of cases of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) which can be treated easily with different treatment modalities and progression of cervical precursors to invasive cancer can be reduced, thus reducing the incidence of cancer cervix.

Conclusion

The study has shown a relatively high prevalence of epithelial abnormalities in cervical smears and conventional Pap smear is a good tool to find cervical dysplasia in population. Periodical cytological screening would go a long way in the early detection of various cervical lesions and help in reducing the incidence of cervical cancer.

Acknowledgement

Amit Jaiswal for preparation of manuscript

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Boyle P, Ferlay J. Cancer incidence and mortality in Europe, 2004. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:481–8. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tristen C, Bergstrom S. Cancer in developing countries. A threat to reproductive health. Lakartidningen. 1996;93:3374–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Juneja A, Sehgal A, Sharma S, Pandey A. Cervical cancer screening in India: Strategies revisited. Indian J Med Sci. 2007;61:34–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller AB, Chamberlain J, Day NE, Hakama M, Prorok PC. Report on a workshop of the UICC project on Evaluation of Screening for Cancer. Int J Cancer. 1990;46:761–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910460502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walton RJ. Editorial: The task force on cervical cancer screening programs. Can Med Assoc J. 1976;114:981. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hakama M, Rasanen-Virtanen U. Eftect of a mass screening program on the risk of cervical cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 1976;103:512–7. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laara E, Day NE, Hakama M. Trends in mortality from cervical cancer in the Nordic countries: Association with organized screening programs. Lancet. 1987;1:1247–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)92695-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson GH, Boyes DA, Benedet JL, Le Riche JC, Matisic JP, Suen KC, et al. Organization and results of the cervical cytology screening program in British Columbia. 1955-85. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1988;296:975–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.296.6627.975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jain DK, Singh P. A study of uterine cervix cancer in India: Sankhya-Indian. J Stat. 1996;58:118–44. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murthy NS, Chaudhary K, Saxena S. Trends in cervical cancer incidence--Indian Scenario. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2005;14:513–8. doi: 10.1097/00008469-200512000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Solomon D, Davey D, Kurman R, Moriarty A, O’Connor D, Prey M, et al. Forum Group Members, Bethesda 2001 Workshop. The 2001 Bethesda system: Terminology for reporting results of cervical cytology. JAMA. 2002;287:2114–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.16.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pan Q, Belinson JL, Li L, Pretorius RG, Qiuo YL, Zhang WH, et al. A thin layer, liquid based pap test for mass screening in an area of China with high incidence of cervical carcinoma: A cross sectional, comparative study. Acta Cytol. 2003;47:45–50. doi: 10.1159/000326474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tuncer ZS, Basaran M, Sezgin Y, Firat P, Mocan Kuzey G. Clinical results of a split sample liquid based cytology (Thin Prep) study of 4,322 patients in a Turkish institution. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2005;26:646–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kapila K, George SS, Al-Shaheen A, Al Ottibi MS, Pathan SK, Sheikh ZA, et al. Changing spectrum of squamous cell abnormalities observed on papanicolaou smears in Mubarak Al Kabeer Hospital, Kuwait, over a 13 year period. Med Princ Pract. 2006;15:253–9. doi: 10.1159/000092986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Insinga RP, Glass AG, Rush BB. Diagnoses and outcomes in cervical cancer screening: A population based study. Am J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;191:105–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fonn S, Bloch B, Mabina M, Carpenter S, Cronje H, Maise C, et al. Prevalence of pre-cancerous lesions and cervical cancer in South-Africa--A multicentre study. S Afr Med J. 2002;92:148–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sadan O, Schejter E, Ginath S, Bachar R, Boaz M, Menczer J, et al. Premalignant lesions of the uterine cervix in a large cohort of Israeli Jewish women. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2004;269:188–91. doi: 10.1007/s00404-002-0371-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tbistle PJ, Chirenje ZM. Cervical cancer screening in a rural population of Zimbabwe. Cent Afr J Med. 1997;43:246–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sadeghi SB, Hsieh EW, Gunn SW. Prevalence of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in sexually active teenagers and young adults: Results of data analysis of mass papanicolau screening of 796, 337 women in the United States in 1981. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1984;148:726–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(84)90555-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daney DD, Woodhouse S, Styer P, Statsney J, Mody D. Atypical epithelial cells and specimen adequacy: Current laboratory practices of participants in the college of American Pathologists Inter laboratory comparison program in cervicovaginal cytology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:203–11. doi: 10.5858/2000-124-0203-AECASA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jamal A, Al-Maghrabi JA. Profile of Pap smear cytology in Western region of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2003;24:1225–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Altaf FJ. Cervical cancer screening with pattern of pap smear. Review of multicenter studies. Saudi Med J. 2006;27:1498–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bar-Am A, Niv J, Yavetz H, Jaffa AJ, Peyser RM. Are Israeli women in a low risk group for developing squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1995;74:472–7. doi: 10.3109/00016349509024412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baram A, Galon A, Schachter A. Premalignant lesions and microinvasive carcinoma of the cervix in Jewish women: An epidemiological study. Br J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;92:4–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1985.tb01040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suprun HZ, Schwartz J, Spira M. Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and associated condylomatous lesions. A preliminary report on 4764 women from Northern Israel. Acta Cytol. 1985;29:334–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Misra JS, Singh U. Results of long term hospital based cytological screening in asymptomatic women. Diagn Cytopathol. 2006;34:184–7. doi: 10.1002/dc.20377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patel TS, Bhullar C, Bansal R, Patel SM. Interpreting epithelial cell abnormalities detected during cervical smear screening — A cytohistologic approach. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2004;25:725–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Misra JS, Srivastava S, Singh U, Srivastava AN. Risk-factors and strategies for control of carcinoma cervix in India: Hospital based cytological screening experience of 35 years. Indian J Cancer. 2009;46:155–9. doi: 10.4103/0019-509x.49155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mulay K, Swain M, Patra S, Gowrishankar S. A comparative study of cervical smears in an urban hospital in India and a population based screening program in Mauritius. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2009;52:34–7. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.44959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Castapeda-Ipiguez MS, Toledo-Cisnernos R, Aguilera-Deigadillo M. Risk factors for cervicovaginal uterine cancer in women in Zecalecos. Salud Publica Mex. 1998;40:330–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bosch FX, Lorincz A, Munoz N, Meijer CJ, Shah KV. The causal relation between human papilloma virus and cervical cancer. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55:244–65. doi: 10.1136/jcp.55.4.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tay SJ, Tay KJ. Passive Smoking associated with high grade squamous intraepithelial lesions. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;93:116–20. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wynder EL, Cornfield J, Schroff PD, Dororswarni KR. A study of environmental factors in carcinoma of cervix. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1954;68:1016–47. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(16)38400-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Castellsague X, Bosch FX, Munoz N, Meijer CJ, Shah KV, de Sanjose S, et al. International Agency for Research on Cancer Multicenter Cervical Cancer Study Group. Male Circumcision, penile HPV infection and cervical cancer in female partners. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1105–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elliott RI. Circumcision and cervical cancer. Br Med J. 1964;2:397–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5406.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Terris M, Wilson F, Nelson JH., Jr Relation of circumcision to cancer of the cervix. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1973;117:1056–66. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(73)90754-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khan MJ, Partridge EE, Wang SS, Schiffman M. Socioeconomic status and the risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 among oncogenic human papillomavirus DNA-positive women with equivocal or mildly abnormal cytology. Cancer. 2005;104:61–70. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chitale AR, Bhuvaneshwari, Krishna UR. Histological assessment of cytologically abnormal smears. Indian J Cancer. 1976;13:324–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sankaranarayanan R, Budukh AM, Rajkumar R. Effective screening programmes for cervical cancer in low and middle-income developing countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79:954–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]